In the years before Saddam Hussein co-opted pesticide production facilities in Iraq to produce chemical weapons, the world’s inspection and verification regimes were designed to govern large-scale chemical manufacturing facilities, which were primarily located in a few regions of the globe. Globalization has reduced the efficacy of the current inspection regimes and opened verification gaps through the proliferation of chemical manufacturing equipment and infrastructure. To better understand the movement and tracking of chemical manufacturing equipment of dual-use2 concern, the Project on Advanced Systems and Concepts for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction (PASCC) at the Naval Postgraduate School contracted with the Board on Chemical Sciences and Technology (BCST) of the National Research Council (NRC) to hold a day-and-a-half workshop on the global movement and tracking of chemical manufacturing equipment. The workshop, held May 12-13, 2014, in Washington, DC, looked at key concerns regarding the availability and movement of equipment for chemical manufacturing, particularly used and decommissioned equipment that is of potential dual-use concern. Though the original statement of task called for an examination of future technology, discussions among the planning committee (see Appendix C for planning committee biographies) along with input received from the stakeholder community during the planning phase made it clear that there were some fundamental questions regarding current technology and controls that required more discussion than originally anticipated. Thus, the focus of the workshop shifted slightly, primarily to address current rather than emerging concerns. In addressing these concerns, the workshop examined today’s industrial, security, and political contexts in which these materials are being produced, regulated, and transferred. The workshop also facilitated discussions about current practices, including consideration of their congruence with current technologies and security threats in the global chemical industrial system. The full statement of task can be found in Appendix A.

Dual-use applications for chemical manufacturing equipment have been recognized as a concern for many years, and export-control regulations worldwide are in place as a result. These regulations, in conjunction with the verification and inspection requirements of Article VI of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), are designed to support nonproliferation of manufacturing equipment suitable for production of chemical warfare agents. In recent years, globalization has changed the distribution of chemical manufacturing facilities around the world. This has increased the burden on current inspection regimes, and increased the amount of manufacturing equipment available around the world. Movement of that equipment, both domestically and as part of international trade, has increased to accommodate these market shifts.

Challenges for Direct Inspection of Production

Since World War I, when industrial dye manufacturing facilities were adapted to produce many of the chemical warfare agents released on the battlefields of Europe, poten-

__________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the workshop summary has been prepared by the workshop rapporteur as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the NRC, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

2 Dual-use items are generally defined as those that have both civilian and military applications.

tial dual-use applications for chemical equipment have been recognized. Reactors, piping, pressure vessels, and other such basic manufacturing equipment, though requiring some specialization for the production of reactive chemical agents, can be adapted and used in processes for the manufacture of chemicals of concern by state or non-state actors. It is this concern that supports the inspection and verification requirements called for under Article VI of the CWC and that underlies some of the policies restricting the movement of manufacturing materials and equipment, such as U.S. export control regulations on manufacturing equipment, and more broadly, the agreements of the Australia Group.3

Many of the current inspection and verification regimes were developed during a time when large-scale chemical manufacturing facilities, including those for specialty chemicals, were largely located within developed countries, which is also where the companies responsible for manufacturing the equipment were based. Initially, the CWC inspection and verification regime covered facilities known to produce chemicals listed in the treaty’s schedules, but this changed in the early 1990s in the wake of the revelation that Saddam Hussein had co-opted pesticide production facilities in Iraq to produce chemical weapons agents. After that “verification gap” was identified, a requirement was developed that instructs signatories to the treaty to declare the presence of Other Chemical Production Facilities4 (OCPFs) within their countries and states that these facilities may be subject to inspection. However, to provide a sense of scale to the challenges faced by the organization, in late 2008 it was reported that approximately 500 OCPFs had undergone inspection. (Matthews, 2008) That same year, the Director-General of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW, 2008) stated:

The layout, design, and characteristics of plant sites are under continued review by industry. Very importantly, globalization is bringing about a massive redistribution and regional migration of chemical production and trade in the world.

In parallel with these movements, there has been an exponential growth in the number of declared OCPFs. Today, the figure is rising in the order of 4,500 to 5,000, depending on the year. Due to their technological features (such as multipurpose process equipment and flexible piping), a number of OCPFs could easily and quickly be re-configured for the production of chemical weapons and are thus highly relevant to the object and purpose of the Convention. This is all the more pertinent in view of the evolving threat posed by terrorism.

In light of these numbers, it becomes clear that direct monitoring of a significant portion of worldwide production facilities for potential production of chemical weapons agents is challenging.

With the limitations of direct inspection and verification of facilities, indirect controls in support of non-proliferation, such as export controls, play a critical role in reducing available production capacity. The restriction and monitoring of the flow of the chemical manufacturing equipment is intended to support non-proliferation by preventing specialized equipment, such as reactors and piping with specific corrosion-resistant coatings, from entering countries where concerns about either state or non-state actors exist.

Monitoring for Movement of Equipment

Monitoring of equipment movement, stockpiling, and acquisition has been used for decades to monitor production of enriched nuclear materials, such as highly enriched uranium, that can be used for the production of nuclear weapons. Aluminum fuel rods used in uranium enrichment centrifuges, for example, have been a long-used, tell-tale sign of production of weapons-grade uranium by state actors. In the United States, utilization of the information derived from these types of movements in countries from Pakistan and North Korea to Iraq and Iran has allowed the government to make critical policy decisions, most notably around counter-proliferation policy. In many ways, production of weapons-grade nuclear materials requires a relatively well known set of procedures and equipment that can be identified as potential threats.

Within the chemical manufacturing world, however, regulators act to place controls and restrictions on access to bulk-scale equipment without inhibiting the availability of this equipment to individuals pursuing legitimate commercial products. In the nuclear arena, the equipment being tracked or controlled is often highly specialized, which is not the case for chemical manufacturing. Within the United States and globally, equipment with features such as specialized coatings to resist corrosion or dual-walled piping—both of which are needed to produce chemical weapons on a large scale—are subject to export controls with the goal of restricting sale and ownership of such equipment to legitimate, verified buyers. As noted in the introduction to this section, however, many of these requirements were initially developed when chemical manufacturing was largely based in the developed world, and globalization has resulted in a significant change in the distribution of manufacturing facilities worldwide.

__________________

3 The Australia Group is an informal forum of countries which, through the harmonization of export controls, seeks to ensure that exports do not contribute to the development of chemical or biological weapons. Coordination of national export control measures assists Australia Group participants to fulfill their obligations under the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention to the fullest extent possible.

4 Under the CWC, OCPFs are defined as facilities that “(a) produced by synthesis during the previous calendar year more than 200 tonnes of unscheduled discrete organic chemicals (DOCs); or (b) comprise one or more plants which produced by synthesis during the previous calendar year more than 30 tonnes of a DOC containing the elements phosphorus, sulfur or fluorine (PSF chemicals)” (OPCW, 2005).

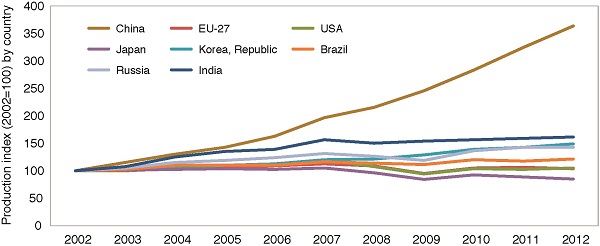

FIGURE 1-1 International comparison of chemical production growth.

SOURCE: CEFIC Chemdata International, 2013, and CEFIC analysis.

This equipment is easiest to control when it is first manufactured. Pristine reactors, for example, can be built and shipped to a specific facility or company owner for its first use. Changes in production may require equipment to be modified, however, and in such cases, when a facility or unit is being decommissioned, companies have four common methods for handling the manufacturing equipment:

- Movement to another production facility or unit within the company,

- Sale of the equipment to another company with a similar product or production line,

- Sending the equipment to auction, or

- Scrapping the equipment.

At these times, though companies are governed by international law and the laws of their home countries, local capacity and regulation for managing decommissioned equipment vary. A large, experienced auction company specializing in manufacturing equipment in Europe, for example, will likely have a greater ability to adhere to requirements for verification of final ownership than a local auction house in a developing country.

The Impact of Globalization

Adding to the challenge of monitoring equipment, chemical manufacturing has become a global endeavor over the past two decades, with the fastest growth occurring in Asia. Figure 1-1 illustrates the rapid change in production growth in the chemical industry since 2002. As a result of these changes, a number of specific challenges to equipment tracking can be identified, examples of which include:

- Increased local capacity for production of manufacturing equipment worldwide;

- Increased movement of equipment within any given country;

- Rapid economic growth leading to rapid changes in the status of facilities, both in terms of company ownership and in the needs of the facilities; and

- Decommissioning of facilities in areas where production has become less profitable.

Taken together, these changes are likely to increase the availability and movement of both general and specialized chemical manufacturing equipment globally, especially in economically emerging regions, and adapting to these changes will be necessary to ensure that such equipment remains out of the hands of individuals wishing to cause harm.

Addressing these challenges will require a multidisciplinary approach, requiring input from individuals with knowledge of chemistry and chemical engineering, experts in policy and non-proliferation, and input from the chemical industry. Such changes are likely to continue as the world economy grows, especially with expected advances in chemical production processes.5 Identifying potential future gaps or areas of concern in the tracking and monitoring processes and possible methods for addressing them would be beneficial.

__________________

5 Examples of anticipated changes in the coming years include increased use of biological materials to produce chemicals and increased availability and functionality of microreactors.

This publication summarizes the presentations and discussions that occurred at the workshop (see Appendix B for the workshop agenda), highlighting the key lessons presented and the resulting discussions among the workshop participants (see Appendix D for a list of attendees). Chapter 2 discusses the global landscape for chemical manufacturing equipment and Chapter 3 examines issues related to the lifetime of chemical manufacturing equipment. Chapter 4 recounts the presentations and discussions on security matters and Chapter 5 looks at the challenges associated with the Internet as a secondary market for used chemical manufacturing equipment. A recurring sentiment from the presentations and resulting discussions was the sense that many companies in the United States and Europe have strong corporate cultures that understand the need for export prohibitions and that promote adherence to existing regulations. The main challenge to non-proliferation comes from the globalization of the chemical industry and the need to help those countries that have only recently built chemical production capabilities develop the knowledge of and expertise to meet the obligations spelled out in these treaties and national regulations.

Chapter 6 summarizes the group discussion that examined a set of questions that were provided to the workshop participants prior to the meeting. This discussion stressed the importance of developing strong partnerships both among companies in the chemical industry and between industry and government.

In accordance with the policies of the NRC, the workshop did not attempt to establish any conclusions or recommendations about needs and future directions, focusing instead on issues identified by the speakers and workshop participants. In addition, the organizing committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop. The workshop summary has been prepared by workshop rapporteurs Kathryn Hughes and Joe Alper as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop.

CEFIC. 2014. The European Chemical Industry: Facts and Figures 2013. Brussels: European Chemical Industry Council. Available at http://asp.zone-secure.net/v2/index.jsp?id=598/765/42548 (accessed 6/25/2014).

Matthews, R. 2008. Other Chemical Production Facilities Inspections. Presentation at CWC 2nd Review Conference Open Forum, 9 April 2008. Available at http://www.opcw.org/index.php?eID=dam_frontend_push&docID=12368 (accessed 6/25/2014).

OPCW. 2005. Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction. Available at http://www.opcw.org/chemical-weapons-convention/verification-annex/part-ix/ (accessed 8/12/2014).

OPCW. 2008. Opening Statement by the Director General to the Second Review Conference. Available at http://www.opcw.org/index.php?eID=dam_frontend_push&docID=1874 (accessed 6/25/2014).