2

The Changing Global Landscape

- The globalization of the chemical industry, and particularly its growth in Asia and Latin America, combined with changes in the technologies used to produce chemicals represent major challenges for tracking chemical manufacturing equipment. (Maennig)

- The number of math, science, and technology graduates produced by China and other countries outside of the United States and Europe portends a future in which the knowledge needed to produce and utilize chemical manufacturing equipment will be more broadly distributed globally. (Maennig)

- Increasing automation of chemical manufacturing, a trend of building smaller chemical production facilities, and the use of biotechnology in chemical manufacturing create challenges and opportunities for chemical weapons inspectors. (Maenning)

- The worldwide proliferation of regulations and international agreements pertaining to chemicals and chemical manufacturing equipment makes it difficult for even well-meaning companies to be in full compliance. (Maennig)

In the workshop’s opening session, Detlef Maennig, an industrial chemist with Evonik Industries representing the European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC), noted that the chemical industry has changed dramatically over the past 20 years in a way that has gone largely unnoticed by the general public. These changes include a shift in the regions where the chemical industry is active and in its product mix as well as the development of new regulations, international cooperative groups and trade alliances, information technologies that more rapidly disseminate technological know-how, and new chemical production technologies, such as biological reactors and microreactors.

The globalization of the chemical industry, and in particular the rapid growth of the industry outside of the United States and Europe, increases the challenges of monitoring the movement and use of chemical manufacturing equipment. One example of this challenge is that locally owned chemical companies in new chemical producing regions may not be aware of the responsibilities under the CWC. They may also lack the internal compliance programs and standards that are applied in regions with an established chemical industry. In addition, the globalization of the chemical industry has created a large pool of people with expertise in the production of dual-use chemical manufacturing equipment who may not be aware of the provisions of the CWC.

Before addressing these changes, Maennig provided some background information on CEFIC, which represents some 29,000 chemical companies spread across Europe. About 600 of these companies are direct members of CEFIC with the rest being represented via their membership in one of the 28 member national chemical federations. In addition, there are 30 companies with associate membership that have operations in Europe but have headquarters elsewhere. CEFIC operates 104 different sector groups with about 4,500 industry experts participating in these groups.

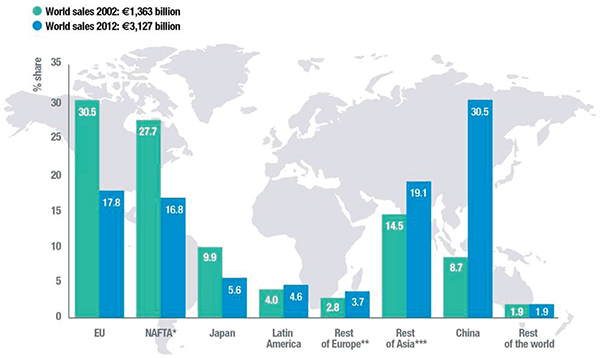

Returning to the subject of change, Maennig noted that the number of state parties that have declared that they have chemical manufacturing facilities rose dramatically between 2001 and 2010, with the largest increase in company numbers occurring in Asia and Latin America. At the same time, global output of chemicals more than doubled (Figure 2-1) and China and the rest of Asia have both surpassed Europe as the leading manufacturers of chemicals. “It used to be that 30 percent of the world’s chemicals came from Europe and 27.7 percent came from North America,” said

FIGURE 2-1 World chemicals output more than doubles as emerging market sales surge.

SOURCE: CEFIC Chemdata International, 2013.

Maennig. Today, he noted, the European Union accounts for only 17.8 percent of chemical sales and North America’s market share has dropped to 16.8 percent (CEFIC, 2014). According to 2012 sales figures, Asian chemical production is now higher than that of Europe plus North America. In fact, China’s sales alone, which total €952 billion in 2012, are almost equal to those of Europe plus North America, at €558 billion and €526 billion respectively. To put these figures in context, Maennig said that Europe’s chemical sales have almost doubled since 1992 while its market share is half of what it was 20 years ago. Yet despite losing market share, Europe is still the world’s leading regions in terms of chemical exports, accounting for 41.6 percent of the world total. Seven member states, led by Germany, France, and The Netherlands, account for 85 percent of the European Union’s chemical sales.

One change that Maennig noted as important for the future of the chemical industry was that the number of math, science, and technology graduates produced by China has soared since 2000 and now surpasses those from Europe and the United States combined. “So we need to be aware that China will not only be what we like to refer to as the world’s chemical workbench, but it will also be a significant contributor to worldwide intellectual property,” Maennig predicted. China also dominates today in terms of capital spending in the chemical industry, with €133.8 billion in capital investments compared to €24.7 billion in North America and €19 billion in Europe.

Another substantial change, said Maennig, has been the growth in the number of medium- and small-scale plants that specialize in producing high-value, high-profitability specialty chemicals, in contrast to the world-scale facilities that produce bulk petrochemicals, chlorine-based chemicals, and fertilizers. “You see this with all of the big players. They are all trying to move more into higher value, value-added products, and away from bulk chemicals,” said Maennig.

An important technological change that is sweeping the chemical industry involves an increasing level of information technology integration. “You don’t see chemical plants anymore that do not run without a distributed control system that is state of the art,” said Maennig. The acts of adding chemicals to reactors by hand or manually turning valves are largely relics of an earlier time, he added. For chemical weapons inspectors, this change means that they have to be aware that they cannot measure inputs and outputs by buckets and valves. On the other hand, production data should all be available from the distributed control systems.

Biotechnology is another significant development for the chemical industry. Maennig said current estimates suggest that by 2020, some 10 percent of global chemical output will be the result of biotechnological processes rather than traditional petrochemical-based processes. He said that he expects that this development will have a significant impact on chemical weapons inspections.

The regulatory landscape for the chemical industry has changed significantly over the past several decades, particularly with regard to export controls for chemicals and chemical manufacturing equipment. There are now regulations governing persistent organic pollutants, ozone depletion, narcotics production, psychotropic substances, money laundering, and terror financing in addition to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) that is most germane to this workshop. There are also other international agreements, such as the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies, the Missile Technology Control Regime, the Nuclear Suppliers Group, and the Australia Group, and a wide landscape of voluntary warning lists, sanctions, and embargoes that individual governments issue. The United States, explained Maennig, has special re-export regulations that companies need to consider as well. “It is very easy to overlook a regulation,” said Maennig. “You need to be very careful and try to follow the regulations as best you can.” He suggested, in fact, that the subject of regulation would make a good future topic of discussion.

The chemical industry’s focus over the past decade has also shifted from one of products to one of developing solutions to challenges, said Maennig. The result of this change in focus is that chemical companies are getting more involved with equipment manufacturers and forging new alliances with energy companies. This move, he explained, is related to sustainability. “When we look into the future, there will be nine billion people on the planet by 2050, so the chemical industry is looking at how it can guarantee that there will be enough food, enough water,” said Maennig. In addition, the world is urbanizing rapidly, and he estimated that 67 percent of the world’s population will live in cities, creating a tremendous demand on infrastructure, water, energy, and traffic. In terms of energy, the chemical industry has been aggressive about developing chemical production technologies that use less energy and is working with other interested partners to provide solutions to these problems.

The final change that Maennig highlighted was the reduction in the time that companies have to bring products to the market than they did in past decades. Joint development of products now seems to be a critical part of the chemical industry. So, too, is life-cycle analysis. Maennig highlighted this change by noting that chemists are creating some 12,000 new substances each day.1

Turning to the subject of the CWC, which has been in force since 1997, Maennig said that what has been happening in Syria argues that the Convention will not stop all production of chemical weapons. One sign of that reality is that the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) has built up its capacity to handle and destroy chemical weapons. What is needed going forward, said Maennig, is better communication between OPCW and the chemical industry. “In the beginning phases of the Chemical Weapons Convention, there was an intense interaction between the chemical industry and the OPCW. But since it has worked so well, there has been less momentum to maintain that part of the dialogue. Now that we see how the international framework is changing, how the security framework is changing, there should be enhanced interaction between the chemical industry and the OPCW,” Maennig said in closing his comments.

In response to a question from Charles Mooney of Xylem, Inc., about the rise of China as a chemical producer, Maennig explained that China got into the field mostly as a producer of bulk drugs and commodities but that bulk production continues in other parts of the world because local production reduces transportation costs and concerns. He noted that China’s chemical industry initially benefited from lower production costs arising from fewer safety and environmental controls compared to those in place in Europe and North America. China, however, is using more sophisticated production techniques to address pollution and safety issues. Maennig estimated that within 5-10 years that there will not be much of a difference in the type of chemistry being done in China in comparison to Europe and North America.

Nancy Jackson, from the Department of State, asked about shifts in worldwide investment in chemical research, in contrast to capital investment. Maennig said that investment in research in China and some of the other rapidly developing countries is still relatively low, particularly in terms of foreign investment.

CEFIC. 2014. The European Chemical Industry: Facts and Figures 2013. Brussels: European Chemical Industry Council. Available at http://asp.zone-secure.net/v2/index.jsp?id=598/765/42548.

__________________

1 The Chemical Abstracts Service estimates approximately 15,000 new substances are added to the registry every day (http://www.cas.org/content/chemical-substances/faqs, accessed July 17, 2014).