2

Identifying and Characterizing

Uncertainty

Key Messages Identified by Individual Speakers

- Benefit–risk assessments are dynamic by nature because the information itself changes over time.

- The goal of a systematic approach to uncertainty might be to improve human judgment, not to automate the process of benefit–risk assessment.

- Several dimensions of uncertainty are inherent to population-based benefit–risk assessments, and operational factors can exacerbate them.

- Finding an approach that can combine results of studies with different designs and data sources might provide a clearer picture of benefits and risks and reduce uncertainty.

- Benefit–risk assessments reflect an interaction among multiple streams of evidence with many stakeholders; understanding the context for each type of evidence could be valuable to the drug evaluation process.

- Stakeholder consultation could help regulators avoid conflating uncertainty regarding the extent of the risk with the willingness to accept that risk.

The first session of the workshop explored several dimensions of the drug decision-making process, examining the sources and types of uncertainties in the research process and how they might relate to, and affect, each other. Speakers from academic research institutions, federal government, and the pharmaceutical industry proposed several principles and approaches to improve the quality of, and reduce the uncertainty associated with, clinical study data. These approaches included finding a scientifically acceptable method to bridge the gap between randomized trials, which focus on proving drug efficacy in a study population, and observational studies, which focus on risk and adverse events in the real world.

KEY SOURCES OF UNCERTAINTY IN BENEFIT–RISK ASSESSMENT AND ASSOCIATED CHALLENGES1

Tarek A. Hammad, Executive Director, Epidemiology, Merck Research Laboratories, Merckv & Co., Inc., provided an overview of the sources of uncertainty in the benefit–risk assessment process. Noting that the common interest of all stakeholders is to understand the causal effects of a given drug, he observed that the challenge for decision making is to make the best possible judgment about how to value study data. This judgment has inherent qualitative and quantitative components, and includes the understanding that benefit–risk assessment is dynamic and that there are clear imbalances in the sources, timing, and nature of information available throughout a drug’s lifecycle (Hammad et al., 2013). For instance, the evidence informing a benefit–risk assessment at the time of approval is limited to tightly controlled randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that are highly reliable for the population being studied, but do not include, by design, categories of patients that will ultimately take a drug. After market approval, once a drug is used in a larger and more diverse population, data about a drug’s effects will arise from sources of varied quality and reliability. As time passes, more information is accrued; including, in particular, safety and adverse event data. If data about efficacy and benefit are not accrued in a timely manner during the postmarket period, the benefit–risk profile will appear to be getting worse over time (Hammad et al., 2013).

According to Hammad, the core uncertainty in the drug review process is that benefit–risk assessments rely on data that represent a group

__________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Tarek A. Hammad, Executive Director, Epidemiology, Merck Research Laboratories, Merck & Co., Inc.

experience, not the effect of a drug on an individual patient. He outlined three distinct, but interrelated, components of uncertainty in evidence.2

The first component, clinical uncertainty, is a function of the research process itself. For example, RCTs by definition must minimize biological variables in the study population, such as age, gender, genetic profiles, and other health issues or treatments. This reduces the value of RCT results outside the trial population. Also, the standard length of a clinical trial is generally too brief to anticipate adverse events with long latency periods, such as in drugs that treat chronic conditions.

The second component, methodological uncertainties, is represented by the fact that RCT methods are tightly constrained to establish evidence in the premarket setting (Hammad et al., 2011), while observational studies are generally employed after the drug is approved to assess real-world risks. Additionally, some RCT methods that are intended to improve trial efficiency might be associated with a reduced ability to characterize all risks, such as randomized withdrawal designs (Hammad et al., 2011).

Statistical uncertainty arises because clinical trials for drug approval are designed to show that a drug works as intended, by evaluating the incremental difference in efficacy between a drug and a comparator, but not necessarily to quantify benefits and risks. In addition, clinical trials involve sampling which, by its nature, introduces the potential for error and thus uncertainty.

Hammad also described a fourth, crosscutting dimension in benefit–risk assessments: operational uncertainty. One component is the challenge and need for making postmarket studies part of the overall research process, given that RCT participants are volunteers and cannot be compelled to participate after a drug has been approved. Also, he noted, benefit–risk assessments do not include discussions to establish a “threshold of risk tolerance” that could differ among stakeholders with varying interests (e.g., regulators vs. payers vs. health care providers vs. patients).

The potential for “confounding by information” on the assessment of benefit–risk balance also exists. For instance, health care practitioners might change their practices based on uncertain information in the public domain, which might hinder efforts to fully evaluate the benefit–risk profile based on observational data (Hammad et al., 2013). Finally, population-based surveillance efforts that might be initiated to mitigate uncertainties are constrained by biases and shortcomings, including a lack of effective infrastructure to make the best use of electronic health records and “big data” associated with drug studies.

According to Hammad, the current regulatory approach to dealing with uncertainty is a version of the precautionary principle; that is, regu-

__________________

2 Classification adopted from Berlin et al., 2012.

lators refrain from taking action when the impact of an uncertain hazard is “morally unacceptable.” Hammad suggested that there are public health consequences to risk aversion, such as denying market access for a drug that could be beneficial or withdrawing a drug from the market or restricting its use when it could provide more benefit than harm (Eichler et al., 2013). Also, from the patient perspective, overadherence to precaution might be conflating two sources of uncertainty: the uncertainty about the extent of the risk with uncertainty about the willingness of the patient to accept the risk. Hammad explained that a patient’s willingness to accept risk is likely to change over time depending on stage of life and severity of disease, which adds to the complexity of drug regulatory decisions. Hammad suggested five considerations and principles to potentially inform the development of a systematic approach to addressing uncertainty (see Box 2-1).

REDUCING UNCERTAINTY THROUGH MAXIMIZING THE VALUE OF EVIDENCE3

Two presenters focused on the quality of evidence available for regulatory decisions: trial registration and participant retention.

Deborah A. Zarin, Director, ClinicalTrials.gov, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, noted that wide public registration of clinical trials, including results and key protocol details, would support the best possible evidence-based decision making. However, she said, not all clinical trials are registered, and not all registered trials can be found. Trials are often registered under names other than those provided in a new drug application, causing these trials to be “invisible” to registry search engines.

Suboptimal participant retention, with resultant missing data, is a long-standing challenge that can contribute to uncertainty in reviewing clinical trial data, because losing participants during the conduct of a clinical trial skews results in unpredictable ways. Michaela Kiernan, Senior Research Scientist, Stanford Prevention Research Center (SPRC), Stanford University School of Medicine, presented one promising innovative retention approach that could help to optimize both high and non-differential retention of subgroups. An ongoing weight loss study at SPRC involves educating potential participants prior to randomization about research

__________________

3 This section is based on presentations by Deborah A. Zarin, Director, ClinicalTrials. gov, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health; Michaela Kiernan, Senior Research Scientist, Stanford Prevention Research Center (SPRC), Stanford University School of Medicine; and material from Characterizing Uncertainty in the Assessment of Benefits and Risks of Pharmaceutical Products: Workshop in Brief (IOM, 2014), also prepared for this project.

BOX 2-1a

Considerations for Designing an Approach

to Addressing Uncertainty

Preserve the Role of Human Judgment

- Systematizing approaches to uncertainty is meant to improve human judgment, not to replace it with an automated process.

Acknowledge the Complexity of the Decision-Making Process

- Context matters: The same set of facts can lead to a different course of action, depending on the decision maker and the unique situation presented by each product.

- Sources of uncertainty (e.g., clinical, methodological, and statistical) are exacerbated by operational challenges.

- Benefit–risk assessment has inherent qualitative and quantitative components to be taken into consideration.

Understand the Dynamic Nature of Benefit–Risk Assessments

- Clear imbalances exist in the sources, timing, and nature of information on benefit and risk.

Listen to the Patient Perspective

- Benefit–risk assessments could benefit from better ways to characterize and incorporate patient perspectives and preferences throughout the lifecycle of a drug.

Identify and Address Knowledge Gaps

- Addressing known shortcomings in study data can improve decision making under uncertainty.

__________________

a This section is based on the presentation by Tarek A. Hammad, Executive Director, Epidemiology, Merck Research Laboratories, Merck & Co., Inc.

methods, trial design, control conditions, random assignments, and the impact of dropouts.

METHODS TO ADDRESS UNCERTAINTY IN THE POSTMARKET PHASE4

A widely recognized challenge in drug decision making is how to incorporate results from postmarket observational studies with clinical

__________________

4 This section is based on the presentation by Sebastian Schneeweiss, Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology, Harvard Medical School.

trial data. Sebastian Schneeweiss, Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology, Harvard Medical School, noted three main sources of uncertainty in drug studies in the pre- and postmarket phase: chance, bias, and representativeness. Chance and bias (e.g., confounding, time-related biases, surveillance bias, and misclassification) affect internal validity. Chance is addressed through calculation of 95 percent confidence intervals. Bias is addressed through various design and analytic approaches such as negative control outcomes, emulating trial populations, extensive adjustment procedures, bias modeling, and sensitivity analyses. Representativeness affects external validity and can be partially addressed in RCTs through evaluation of subgroups.

Schneeweiss noted that in general, sources of uncertainty vary between RCTs and observational studies and also differently affect the assessment of benefits and harms. RCTs are typically the source for information about benefit or efficacy, while large observational claims data studies are typically the source for information about adverse events in real-world populations.

To collectively provide the most valid, comprehensive, and affordable information for decision makers, Schneeweiss said, a benefit–risk assessment should include evidence from multiple study types with different data sources, intelligently arranged to maximize information available to a decision maker while complementing each study’s methodological weaknesses.

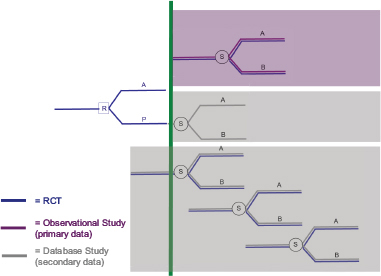

He proposed an optimal framework for these interlocking RCT and observational studies, designed to reduce uncertainty and to complement each other in speed, validity, precision, and generalizability (see Figure 2-1). Conducting multiple studies in a cohesive manner can effectively retain patient populations across study designs to gather essential information on benefits and harms that would not be possible in an RCT or observational study alone.

Monitoring settings, such as the Mini-Sentinel surveillance system developed by FDA and its partners, illuminate the need for formal approaches to assessing benefits and harms, according to Schneeweiss. Broad population-based systems that monitor the safety of drugs require the upfront creation of clear decision rules that govern when the information gathered rises to the level of requiring a safety alert to the public. False signals on the safety of a drug—either failing to identify a safety concern or identifying a purported safety issue that is not real—are equally problematic. In the first case, patients would be exposed to unnecessary risk and in the second case, unwarranted concerns would be raised and a safe medication underused. A single probability (p-value) or predefined threshold underlying a decision rule does not adequately consider the balance of benefits and harms for a particular medicine. Schneeweiss

FIGURE 2-1 A system of proactively, prospectively designed interlocking randomized controlled trial (RCT) and observational studies to reduce uncertainty, retain patient populations, and gather information that would not be possible in an RCT or observational study alone.

NOTES: A = drug A; B = drug B; P = placebo; R = randomization; and S = selection. The green vertical line indicates the time of market authorization for a drug. The RCT conducted prior to market authorization would include health claims or electronic health record data for all trial participants prior to the start of the trial. Obtaining these data, with the permission of patients, facilitates the characterization of the RCT patient population via the same data source used in a later observational study, thereby maintaining the comparability of subgroups across study design. Identifying a subgroup within the observational study that mimics the original RCT study population will help to tackle the issue of representativeness and reduce uncertainty. The observational studies suggested in the figure indicate three unique designs: (1) one observational study with primary data (purple shaded area) in which an RCT-like subgroup is identified in a cohort study with primary data in order to reproduce RCT findings to calibrate observational findings in the postmarket setting; (2) one observational follow-on study (middle shaded area) in which the RCT placebo group is retained and self-selects to receive drug A or drug B, thereby assessing a non-randomized finding in the original RCT population; and (3) a monitoring system of sequential observational database studies that maintain an RCT-like patient subgroup that mimics the original trial population over time. The combined effect of these studies is to provide valid and comprehensive information for benefit and risk decision makers in an integrated and cost-effective manner.

SOURCE: Schneeweiss, 2014. Presentation at the IOM workshop series on Characterizing and Communicating Uncertainty in the Assessment of Benefits and Risks of Pharmaceutical Products.

suggested that decision rules for safety monitoring systems should incorporate decision-analytic and value-of-information approaches that would allow monitoring decisions to be made over time and incorporate answers to the following questions:

- What is the availability of an alternative drug?

- How effective is the monitored drug compared to an alternative?

- How severe is the disease that the drug treats (e.g., skin rash vs. cancer)?

- How severe is the safety concern of interest?

- What is the prognosis of the population without any treatment?

Many of these questions require significant decision-maker input and might vary by population. Schneeweiss asserted that epidemiologic studies or monitoring systems should be constructed to provide the relevant information for decision makers (e.g., risk differences, not only ratios) as validly as possible. Mini-Sentinel’s Prospective Routine Observational Monitoring Program Tools (PROMPT) modules consisting of preprogrammed and tested analytic code that is applied to an existing common data model can provide this in an expedited manner (Gagne et al., 2014).

APPROACHES TO ASSESSING INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL VALIDITY OF RCTs5

John P. A. Ioannidis, C. F. Rehnborg Professor in Disease Prevention, Stanford University; and Professor of Health Research and Policy, and Director of SPRC, Stanford University School of Medicine, presented results from approaches he has used to assess the internal and external validity of RCTs.

When trials have design flaws, their effect sizes can be exaggerated. One study (Savovic et al., 2012) combined data from nearly 2,000 RCTs with the goal of ascertaining the influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates. Study design characteristics included generation of randomization sequence, allocation concealment, and blinding (or not). On average, Ioannidis said, trials that do not have clear generation of their randomization sequence, or have inadequate or unclear allocation concealment, tend to have inflated effect sizes compared to those that do. The difference is about 10 percent on a relative scale, but, he noted, it can make a big difference depending on the out-

__________________

5 This section is based on the presentation by John P. A. Ioannidis, C. F. Rehnborg Professor in Disease Prevention, Stanford University; and Professor of Health Research and Policy, and Director of SPRC, Stanford University School of Medicine.

come of interest (e.g., mortality or another objective outcome compared to something that is subjective). Mortality, he observed, seemed to be least affected by study design. Subjective outcomes tend to be affected the most by the validity of study design, ranging from 20 to 30 percent.

As some workshop participants had also noted, Ioannidis argued that to address external generalizability, a trial needs to be compared against other trials done in the same field on questions that are relevant. He emphasized that the outcomes of interest are whether one drug is better than another (rather than a placebo) and the relative uncertainty of one drug versus another.

This page intentionally left blank.