8

Population Perspectives: Understanding Health Trends and Evaluating the Health Care System

The earlier chapters on predisease pathways, positive health, environmentally induced gene expression, and personal ties place strong emphasis on preventing disease, maintaining allostasis, and promoting well-being at levels comparatively proximal to the individual (social, psychological, neurophysiological). The chapters addressing collective properties of communities and inequality focus on more intermediate levels whereby environmental and social structural factors influence health. This chapter focuses explicitly on questions of population health at the macro level. Four primary issues are considered: (1) time trends and spatial variation in population health; (2) accounting for such trends, with particular emphasis given to social and behavioral factors; (3) understanding links between population health and the macroeconomy; and (4) evaluating the health care system. An important crosscutting research priority, among several others delineated below, is to account for population health processes by linking them via multilevel analyses to behavioral, psychosocial, and environmental factors described in earlier chapters.

TIME TRENDS AND SPATIAL VARIATION IN POPULATION HEALTH

Brief summaries are provided below of health trends in life expectancy and disability, both within the United States and in other countries. Changing rates of communicable diseases (e.g., sexually transmitted diseases and tuberculosis) are also examined. Finally, various indicators of child health

(e.g., infant mortality, birth weight, asthma, and other respiratory conditions) are reviewed. Some of these population trends show health improvements across time; others point to increasing health problems. Behavioral and psychosocial factors are implicated in both. A major international data source on health trends is the set of Demographic and Health Surveys. 1 An overarching theme is that the maintenance and improvement of population health have been and continue to be due as much to changes in broader socioeconomic and environmental forces as to more microscopically based biobehavioral science. Understanding and facilitating improvements in socioeconomic conditions, general public health and sanitation, and private and public policies affecting lifestyle have accounted for the bulk of historical changes in population health and very likely recent advances as well (Rose, 1992).

Life Expectancy

Health varies substantially across and within countries. For example, in 1998 life expectancy in Sierra Leone was 37 years and in Japan it was 80 years. Ninety percent of this range, however, is covered by variation across counties within the United States. The range in life expectancy between females born in Stearns County, Minnesota, and males born in various counties in South Dakota is 22.5 years and extends to 41.3 years when race-specific life expectancy is calculated (WHO, 1999). Over time, life expectancy in the United States has risen from 47 years in 1900 to 78 years in 1995. Table 1 shows the changes in life expectancy at birth between approximately 1910 and 1998 in selected countries.

On average, people in richer countries live longer and have higher-quality lives than people in poorer countries. Within countries, at the city, county, and regional levels, people with higher socioeconomic status are on average in better health than those with lower socioeconomic status. As described in Chapter 7, there is also considerable variation across racial and ethnic categories that interacts with socioeconomic status.

Disability

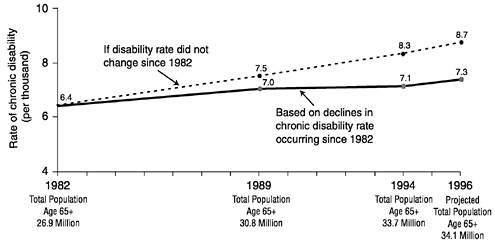

Recent research shows clearly that chronic disease disability rates are falling in the United States. Figure 1 shows the proportion of the elderly who were disabled in 1982, 1984, 1989, and 1994. Disability is measured as impairments in activities of daily living (ADLs, such as bathing, toileting)

|

1 |

The data are available electronically: Demographic and Health Surveys: http://www.measuredhs.com. |

TABLE 1 Life Expectancy at Birth for Selected Countries

|

Around 1910 |

1998 |

|||

|

Country |

Males |

Females |

Males |

Females |

|

Australia |

56 |

60 |

75 |

81 |

|

Chile |

29 |

33 |

72 |

78 |

|

England and Wales |

49 |

53 |

75 |

80 |

|

Italy |

46 |

47 |

75 |

81 |

|

Japan |

43 |

43 |

77 |

83 |

|

New Zealand a |

60 |

63 |

74 |

80 |

|

Norway |

56 |

59 |

75 |

81 |

|

Sweden |

57 |

59 |

76 |

81 |

|

United States |

49 |

53 |

73 |

80 |

or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs, such as the ability to perform light household work, use the telephone). The data, from the National Long-Term Care Survey, are for a representative sample of the elderly in each year. The questions are the same in each survey, so the responses give the most accurate available measure of changes in disability over time.

a Excluding Maoris.

SOURCE: WHO, 1999.

In 1982 and 1984 nearly 25 percent of the elderly were disabled. By 1994 disability had declined to 21 percent, a reduction of over 1 percent per year. Furthermore, disability decline is more rapid in the second half of the time period (1989-1994) than the first half (1984-1989). These findings have been confirmed in other data as well (Freedman and Martin, 1998), suggesting the trend is not an artifact of this particular sample.

Sketchier evidence suggests that the decline in elderly disability has occurred throughout the developed world. Rates of disability and institutionalization among the elderly in various developed countries, compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (Jacobzone, 2000), have been declining over time in most countries. The decline is only modest in some countries (e.g., the United Kingdom) but is rapid in others (e.g., Japan). The average rate of decline among countries where disability rates are falling is 2.3 percent per year. In only two countries have rates of severe disability increased (Australia and Canada), but even there the rates of institutionalization are falling. Such rates have been falling as well in four of the five countries for which there are time series data, although the decline is generally less rapid than the decline in the rate of severe disability. The exception is France, where institutionalization rates have been increas-

FIGURE 1 Changes in chronic disability among the elderly, 1982-1996.

SOURCE: Manton et al. (1997).

ing, perhaps reflecting a change in the location of care. Rates of severe disability in France, however, are declining rapidly.

Overall, these changes in disability have been sufficiently large for some to argue that health promotion might solve the long-term problems of financing public medical care systems (Singer and Manton, 1998). Behavioral, environmental, and psychosocial factors are, as we argue throughout this report, key routes to such health promotion.

Communicable Diseases

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and tuberculosis are among the most important communicable diseases in the United States. The incidence of reported chlamydial infections and viral STDs has steadily increased in recent years, while the incidence of gonorrhea has generally declined. Levels of syphilis vary among different population subgroups but have reached record lows since 1995. Vaginal infections such as trichomonas and bacterial vaginosis have probably remained high, although surveillance for these conditions is rudimentary. Table 2 shows the estimated incidence and prevalence of STDs in the United States in 1996. 2

The number of reported cases of gonorrhea has generally declined,

|

2 |

The full report is available online from the Kaiser Family Foundation: http://www.kff.org/content/archive/1447/std_rep.pdf. |

TABLE 2 Estimated Incidence and Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 1996

|

Sexually Transmitted Diseases |

Incidence |

Prevalence |

|

Chlamydia |

3 million |

2 million |

|

Gonorrhea |

650,000 |

— |

|

Syphilis |

70,000 |

— |

|

Herpes |

1 million |

45 million |

|

Human papilloma virus |

5.5 million |

20 million |

|

Hepatitis B |

77,000 |

750,000 |

|

Trichamoniasis |

5 million |

— |

|

Bacterial vaginosis |

No estimate |

— |

|

HIV |

20,000 |

560,000 |

starting in the mid-1970s with the introduction of the national gonorrhea control program. A disproportionate share of the decline occurred among older white populations, with infection rates remaining relatively high among minority groups and adolescents. In 1996 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 325,000 new cases of gonorrhea (CDC, 1999b). Because previous investigations have shown that only about half of all diagnosed gonorrhea cases are reported to public health authorities, total gonorrhea infections are estimated to be 650,000 in Table 2.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 1998.

HIV infection trends in the United States show that in the mid-1970s HIV was transmitted primarily among homosexual and bisexual men. The virus entered the injection-drug-using populations in the 1980s and rapidly spread during that decade. Limited heterosexual transmission occurred until the 1980s. Since 1989 the greatest proportional increase in reported AIDS cases has been among heterosexuals, with this trend expected to continue (Rosenberg, 1995). New methods of estimating HIV incidence and prevalence (Holmberg, 1996) yielded an estimate of 41,000 new HIV infections annually, with between 700,000 and 800,000 prevalent HIV infections. The introduction of protease inhibitors may increase the number of prevalent infections by extending the life of HIV-infected people. Approximately half of the incident and three-quarters of prevalent infections were estimated to have been sexually transmitted. Globally, the incidence of HIV is much higher than in the United States, with an estimated 5.8 million new infections annually and more than 30 million persons currently living with HIV (UNAIDS, 1998). More than 90 percent of the global total has been spread sexually.

An important priority for future research is to improve the accuracy of these estimates. Most STD incidence and prevalence estimates are derived

from multiple populations, few of which are representative national surveys, such as NHANES or the national reporting system for AIDS. Establishing nationally representative surveillance for the full range of STDs would help narrow the uncertainty in current estimates. For example, the true number of STD infections could be as low as 10 million or as high as 20 million. The current point estimate is 15.3 million.

Potential improvement in the U.S. STD epidemic could ensue from full implementation of the national prevention and control program identified by the expert panel assembled by the Institute of Medicine (Eng and Butler, 1997). The program focuses on improving public awareness and education, reaching adolescents and women, and instituting effective culturally appropriate programs to promote healthy behavior by adolescents and adults. Additional targets are integrating public health programs, training health care professionals, and modifying messages from the mass media. Improved surveillance of STD incidence and prevalence rates will be necessary to document the progress of such initiatives.

Turning to global tuberculosis, 6.7 million new cases and 2.4 million deaths were estimated in 1998 (Murray and Salomon, 1998). Based on current tends in implementation of the World Health Organization 's strategy of directly observed, short-course treatment, a total of 225 million new cases and 79 million deaths from tuberculosis are expected between 1998 and 2030 (Murray and Salomon, 1998). Active case finding using mass miniature radiography could save 23 million lives over this period, which underscores the importance of prevention. Single-contact treatments for TB could avert 24 million new cases and 11 million deaths. Combined with active screening, single-contact treatments could reduce TB mortality by 40 percent.

In the United States the situation is quite different. Table 3 shows the number of reported cases of TB from 1975 to 1992 (CDC, 1999d). The rapid decline in TB cases from 1975 to 1986 was followed by an increase through 1991. However, in 1998 a total of 18,361 TB cases were reported in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, a decrease of 8 percent from 1997 and 31 percent from 1992, the height of the TB resurgence. The 1998 rate of 6.8 per 100,000 population was 35 percent lower than in 1992 (10.5) but remained above the national goal for 2000 of 3.5 per 100,000 (CDC, 1999a).

Considering infectious diseases more generally and on a longer time scale, infectious disease mortality declined during the first eight decades of the twentieth century from 797 deaths per 100,000 people in 1900 to 36 deaths per 100,000 in 1980. The overall general decline was interrupted by a sharp increase in mortality due to the 1918 influenza epidemic. From 1938 to 1952 the decline was particularly rapid, with mortality decreasing by 8.2 percent per year. Pneumonia and influenza were responsible for the

TABLE 3 Tuberculosis Cases, Case Rates, Deaths, and Death Rates per 100,000 Population: United States, 1975-1998

|

Tuberculosis Cases |

Tuberculosis Deaths |

|||||||

|

Percent Change |

Percent Change |

|||||||

|

Year |

Number |

Rate a |

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate a |

Number |

Rate |

|

1975 |

33,989 |

15.9 |

— |

— |

3,333 |

1.6 |

-5.1 |

-5.9 |

|

1976 |

32,105 |

15.0 |

-5.5 |

-5.7 |

3,130 |

1.5 |

-6.1 |

-6.3 |

|

1977 |

30,145 |

13.9 |

-6.1 |

-7.3 |

2,968 |

1.4 |

-5.2 |

-6.7 |

|

1978 |

28,521 |

13.1 |

-5.4 |

-5.8 |

2,914 |

1.3 |

-1.8 |

-7.1 |

|

1979 |

27,669 |

12.6 |

-3.0 |

-3.8 |

2,007 b |

0.9 b |

-31. b |

-30.8 b |

|

1980 |

27,749 |

12.3 |

+0.3 |

-2.4 |

1,978 |

0.9 |

-1.4 |

0.0 |

|

1981 |

27,373 |

11.9 |

-1.4 |

-3.3 |

1,937 |

0.8 |

-2.1 |

-11.1 |

|

1982 |

25,520 |

11.0 |

-6.8 |

-7.6 |

1,807 |

0.8 |

-6.7 |

0.0 |

|

1983 |

23,846 |

10.2 |

-6.6 |

-7.3 |

1,779 |

0.8 |

-1.5 |

0.0 |

|

1984 |

22,255 |

9.4 |

-6.7 |

-7.8 |

1,729 |

0.7 |

-2.8 |

-12.5 |

|

1985 |

22,201 |

9.3 |

-0.2 |

-1.1 |

1,752 |

0.7 |

+1.3 |

0.0 |

|

1986 |

22,768 |

9.4 |

+2.6 |

+1.1 |

1,782 |

0.7 |

+1,7 |

0.0 |

|

1987 |

22,517 |

9.3 |

-1.1 |

-1.1 |

1,755 |

0.7 |

-1.5 |

0.0 |

|

1988 |

22,436 |

9.1 |

-0.4 |

-2.2 |

1,921 |

0.8 |

+9.5 |

+14.3 |

|

1989 |

23,495 |

9.5 |

+4.7 |

+4.4 |

1,970 |

0.8 |

+2.6 |

0.0 |

|

1990 |

25,701 |

10.3 |

+9.4 |

+8.4 |

1,810 |

0.7 |

-8.1 |

-12.5 |

|

1991 |

26,283 |

10.4 |

+2.3 |

+1.0 |

1,713 |

0.7 |

-5.4 |

0.0 |

|

1992 |

26,673 |

10.5 |

+1.5 |

+1.0 |

1,705 |

0.7 |

-0.5 |

0.0 |

|

1993 |

25,287 |

9.8 |

-5.2 |

‘-6.7 |

1,631 |

0.6 |

-4.3 |

-14.3 |

|

1994 |

24,361 |

9.4 |

-3.7 |

-4.1 |

1,478 |

0.6 |

-9.4 |

0.0 |

|

1995 |

22,860 |

8.7 |

-6.2 |

-7.4 |

1,336 |

0.5 |

-9.6 |

-16.7 |

|

1996 |

21,337 |

8.0 |

-6.7 |

-8.0 |

1,202 |

0.5 |

-10.0 |

0.0 |

|

1997 |

19,851 |

7.4 |

-7.0 |

-7.5 |

1,166 |

0.4 |

-3.0 |

-20.0 |

|

1998 |

18,361 |

6.8 |

-7.5 |

-8.1 |

... |

... |

... |

... |

|

a Per 100,000 population. b The large decrease in 1979 occurred because late effects of tuberculosis (e.g., bronchiectasis or fibrosis) and pleurisy with effusion (without mention of cause) are no longer included in tuberculosis deaths. Ellipses indicate data are not available. SOURCE: Data from CDC, 1999d, Table 1. |

||||||||

largest number of infectious disease deaths throughout the century. Although tuberculosis caused almost as many deaths as pneumonia and influenza early in the century, TB mortality dropped off sharply after 1945. Infectious disease mortality increased in the 1980s and early 1990s in persons aged 25 years and older, due mainly to the emergence of AIDS in 25-to 64-year-olds and to a lesser degree to increases in influenza and pneumonia deaths in persons aged 65 and older. Although most of the twentieth century was marked by declining infectious disease mortality, substantial year-to-year variations and recent increases emphasize the dynamic nature of infectious diseases and the need for preparedness to address them. A considerable effort in this direction was stimulated by a 1992 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report focused on emerging infectious diseases. A wider-ranging multidisciplinary program emphasizing emerging infectious diseases of wildlife, including threats to human health, (Daszak et al., 2000) is notable for its integrative consideration of ecology, pathology, and population biology of host-parasite systems and the emphasis on investigations incorporating individual, population, and environmental perspectives.

Child Health

In the United States the overall infant mortality rate has decreased rapidly since 1960. Between 1960 and 1994 the rate fell from 24.9 to 8.0 infant deaths per 1,000 live births. Between 1960 and 1992 the infant mortality rate decreased by 69 percent among whites, 62 percent among African Americans, 68 percent among Asians, and 77 percent among Native Americans. Nevertheless, as of 1992 there were considerable racial and ethnic disparities in the infant mortality rate (see also Chapter 7). The African American infant mortality rate of 16.8 infant deaths per 1,000 live births was 2.4 times higher than the white rate of 6.9. The Native American rate of 9.9 infant deaths per 1,000 live births was second highest, and the Asian rate of 4.8 per 1,000 live births was lowest.

Two other trends of concern in the health of children that are implicated in longer-term negative health consequences are the rate of low-birth-weight babies and the teen birth rate. Nationally, the percent of live births weighing less than 5.5 lbs. (a standard indicator of low birth weight) was 6.8 in 1985 and 7.4 in 1996. The number of births to teenagers between 15 and 17 per 1,000 females in this age category rose from 31 in 1985 to 34 in 1996. There was substantial variation across states in these two statistics. For example, in 1996 the low-birth-weight rate was 4.8 percent in New Hampshire, 9.9 percent in Mississippi, and 14.3 percent in the District of Columbia. The teen birth rate ranged from 15 in New Hampshire to 52 in Mississippi and 79 in the District of Columbia (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 1999).

When assessing the health of children, it is important to examine the prevalence of chronic health conditions. Children with persistent health problems are more likely to miss school and require medical assistance and follow-up. Such chronic problems also pose difficulties for the parents, who may experience emotional stress, often lose days from work, and incur additional medical expenses associated with recurrent medical visits and follow-up care. The circumstances of both children and their parents in this kind of persistent difficult environment contribute to the predisease pathways described in Chapter 2.

Asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood, affecting an estimated 4.8 million children. It is one of the leading causes of school absenteeism, accounting for over 10 million missed school days each year (U.S. DHHS, 1996). In addition, managing asthma is expensive and imposes financial burdens on the families of people who have it. In 1990 the cost of asthma to the U.S. economy was estimated to be $6.2 billion, with the majority of the expense attributed to medical care. A 1996 analysis found the annual cost of asthma to be $14 billion (CECS, 1998).

Table 4 shows the number of children per 1,000 children aged 0-17 in 1993 with a diversity of chronic conditions (NCHS, 1993). Over the past 20 years, respiratory conditions have been the most prevalent type of chronic health problem experienced by children aged 0-17. Rates for most of the chronic health problems identified in Table 4 were fairly constant during that time period, with the exception of chronic respiratory conditions, which showed sizable increases from 1982 to 1993. For example, rates of chronic bronchitis rose from 34 per 1,000 children in 1982 to 59 per 1,000 in 1993 (a 76 percent increase). Similarly, rates of asthma rose 79 percent, going from 40 cases per 1,000 in 1982 to 72 cases per 1,000 in 1993 (NCHS, 1982-1993).

Risk Factors

In a widely cited paper McGinnis and Foege (1993) showed that unhealthy behaviors and environmental exposures were the “actual causes of death” that accounted for 50 percent of all U.S. mortality. Heading the list of causes were tobacco (19 percent), diet/activity patterns (14 percent), and alcohol (5 percent). Smoking has transformed lung cancer from a virtually unknown disease in 1900 to the leading cause of cancer deaths in 1999, accounting with environmental tobacco smoke and interactions with other exposures (e.g., radon) for more than 90 percent of lung cancer deaths each year. Smoking is also the leading cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic bronchitis and emphysema (Warner, 2000). The prevalence of smoking has dropped from 45 percent in 1963, the year prior to publication of the Surgeon General's report on smoking and health (U.S.

DHEW, 1964), to 25 percent in 1997 (CDC, 1999c). Based on projections of the demographics of smoking, even in the absence of stronger tobacco control education and policy, and assuming no change in youth initiation of smoking, prevalence should continue to fall over the next 20 years, leveling off at approximately 18 percent of adults (Mendez and Warner, 1998; see also).

TABLE 4 Selected Reported Chronic Conditions, Number per 1,000 Persons, by Age: United States, 1993

|

Type of Chronic Condition |

All Ages Under |

18 Years |

|

Selected conditions of the genitourinary, nervous, endocrine, metabolic, and blood-forming systems: |

||

|

Goiter or other disorders of the thyroid |

16.3 |

1.9 |

|

Diabetes |

30.7 |

1.5 |

|

Anemias |

15.4 |

8.6 |

|

Epilepsy |

5.3 |

5.4 |

|

Migraine headache |

43.3 |

13.2 |

|

Neuralgia or neuritis, unspecified |

2.7 |

0.2 |

|

Kidney trouble |

15.1 |

4.7 |

|

Bladder disorders |

15.8 |

3.4 |

|

Diseases of the prostate |

8.0 |

– |

|

Disease of female genital organs |

21.0 |

2.6 |

|

Selected circulatory conditions: |

||

|

Rheumatic fever with or without heart disease |

7.9 |

1.2 |

|

Heart disease |

83.6 |

20.3 |

|

Ischemic heart disease |

28.1 |

0.3 |

|

Heart rhythm disorders |

35.9 |

14.9 |

|

8.7 |

0.4 |

|

|

19.5 |

14.1 |

|

|

7.6 |

0.5 |

|

|

Other selected diseases of the heart, excluding hypertension |

19.6 |

5.0 |

|

High blood pressure (hypertension) |

108.3 |

3.1 |

|

Cerebrovascular disease |

13.2 |

1.0 |

|

Hardening of the arteries |

7.0 |

– |

|

Varicose veins of the lower extremities |

30.0 |

0.6 |

|

Hemorrhoids |

39.8 |

0.2 |

|

Selected respiratory conditions: |

||

|

Chronic bronchitis |

54.3 |

59.3 |

|

Asthma |

51.4 |

71.6 |

|

Hay fever or allergic rhinitis without asthma |

93.4 |

56.7 |

|

Chronic sinusitis |

146.7 |

79.6 |

|

Deviated nasal septum |

7.0 |

0.7 |

|

Chronic disease of the tonsils or adenoids |

11.0 |

26.4 |

|

Emphysema |

7.6 |

0.7 |

|

SOURCE: Data from NCHS, 1993. |

||

DHEW, 1964), to 25 percent in 1997 (CDC, 1999c). Based on projections of the demographics of smoking, even in the absence of stronger tobacco control education and policy, and assuming no change in youth initiation of smoking, prevalence should continue to fall over the next 20 years, leveling off at approximately 18 percent of adults (Mendez and Warner, 1998; see also).

Of adult Americans, 24.7 percent were smokers in 1997 (CDC, 1999c). Although a greater percentage of men smoke than women (27.6 percent and 22.1 percent, respectively), the gap between the two genders has declined gradually over time. Racial and ethnic differences in smoking prevalence are substantial, ranging from 16.9 percent for Asians and Pacific Islanders to 34.1 percent for Native Americans and Native Alaskans. Smoking rates vary substantially by age, with prevalence declining in the fourth and subsequent decades of life. Smoking cessation, the principal determinant of the decline in prevalence with age, rises significantly with age.

An important research challenge for demographers is the development of more effective ways of assessing smoking initiation. In the 1999 Monitoring the Future Survey, 34.6 percent of high school seniors had smoked within the previous 30 days. 3 The comparable figures for tenth and eighth graders were 25.7 percent and 17.5 percent, respectively. The interpretive problem with these figures, from the point of view of health risk, is that, while 30-day prevalence rates were rising during the 1990s, measures of regular and heavy smoking (e.g., half a pack or more per day) were not. While the latter clearly point to increased health risk, it is unclear what risks follow from the 30-day prevalence rates among youth.

Since the inception of the antismoking campaign in 1964, the most notable change in smoking prevalence is by education class. In 1965, the year following the first Surgeon General's report, less than 3 percentage points separated the prevalence of smoking among college graduates (33.7 percent) from that of Americans who did not graduate from high school (U.S. DHHS, 1989). By 1997 prevalence among college graduates had fallen by nearly two-thirds to 11.6 percent. Among people without a high school diploma, in contrast, prevalence had fallen by only one-sixth (to 30.4 percent; CDC, 1999c; Warner, 2000). Although considerable speculation has been put forth about the reasons for this disparity, this is an important future research direction, directly linked to those of and Chapter 7, where the social and behavioral sciences are particularly prominent.

Dietary factors and sedentary activity patterns together account for at least 300,000 deaths each year (McGinnis and Foege, 1993). Dietary fac-

|

3 |

The data are available electronically: . |

tors have been associated with cardiovascular diseases (coronary artery disease, stroke, and hypertension), cancers (colon, breast, and prostate), and diabetes mellitus (U.S. DHHS, 1988). Physical inactivity has been associated with an increased risk for heart disease (Manson et al., 1992; Paffenberger et al., 1990) and colon cancer (Lee et al., 1991). The interdependence of dietary factors and physical activity patterns as risk factors for obesity has received considerable attention (Mokdad et al., 1999; Wickelgren, 1998; Hill and Peters, 1998; Tauber, 1998). Understanding these interactions as part of a more mechanistic characterization of predisease pathways (Chapter 2) to a range of cardiovascular diseases and cancers is an important research direction requiring integrative perspectives (see Chapter).

Alcohol and illicit drug use are associated with violence, injury (particularly automobile injuries and fatalities), and HIV infection (injecting drugs with contaminated needles). The annual economic costs to the United States from alcohol abuse are estimated to be $167 billion, and the costs from drug abuse are estimated to be $110 billion (U.S. DHHS, 2000). Among adolescents alcohol is the most frequently used substance among the alcohol/illicit drug items. In 1997, 21 percent of adolescents aged 12-17 years reported drinking alcohol in the last month. Such use has remained at about 20 percent since 1992. Eight percent of this age group reported binge drinking and 3 percent were heavy drinkers (five or more drinks on the same occasion on each of five or more days in the last 30 days). Data from 1998 show that 10 percent of adolescents aged 12-17 years reported using illicit drugs in the last 30 days. This rate is significantly lower than in the previous year and remains well below the all-time high of 16 percent in 1979. Current illicit drug use had nearly doubled for those aged 12 to 13 years between 1996 and 1997 but then decreased between 1997 and 1998. Among adults binge drinking has remained at the same approximate level of 16 percent since 1988, with the highest current rate of 32 percent among adults aged 18 to 25 years. Illicit drug use has been near the present rate of 6 percent since 1980. Men continue to have higher rates of illicit drug use than women, and rates are higher in urban than in rural areas (U.S. DHHS, 2000).

The above data summarize population-level profiles of adverse health behaviors (smoking, obesity and physical inactivity, alcohol and illicit drug use). Consistent with the integrative theme guiding this report (see Chapter 1), there is a great need for broadening research agendas around these topics. On the one hand, the behavioral and social sciences can help identify precursors (e.g., personality factors, coping styles, socialization processes, work and family stress, peer and community influences) to poor health practices (see Chapter 2, Chapter 5, and Chapter 6). Understanding the mechanisms through which poor health behaviors translate to chronic disease requires,

however, that the above processes be linked to gene expression and multiple pathophysiological systems. It also requires attending to the reality that many of the above risk factors (behavioral and physiological) co-occur and have multiple health consequences (see discussion of co-occurring risk and comorbidity in Chapter 2).

From the integrative perspective, it is important to recognize that many of the above behavioral, psychological, social, and environmental factors are driven by broad social structural influences, such as socioeconomic inequality and racial/ethnic discrimination and stigmatization (see Chapter 7). Thus, macro-level forces must also be part of the integrative agenda. Finally, from the perspectives of prevention and treatment, the social and behavioral sciences point to diverse venues for avoiding, offsetting, or reversing these poor health practices (see Chapter 3 and Chapter 9). This report calls for deeper understanding of these interacting processes and thus requires coming at the question of population health risk from many diverse but related angles.

ACCOUNTING FOR MACRO-LEVEL HEALTH PATTERNS

An integrative perspective is required both to understand the antecedents and consequents of behavioral health risks and to account for macrolevel changes in health, such as gains in life expectancy, declining rates of disability, the spread of STDs, and infant mortality and childhood diseases. These topics and needed agendas following from them are described below.

Life Expectancy

The dramatic increase in life expectancy in the United States during the twentieth century is attributable largely to primary prevention interventions (Bloom, 1999), such as improved sanitation, housing, nutrition, and new technologies for food preservation. The decrease of 6 percent per decade in chronic disease prevalence in males between 1910 and 1985 was achieved with relatively primitive medical and public health technologies and when little was known about the mechanisms of chronic disease processes at relatively advanced ages (Fogel, 1999). Recent data suggest that nutritional factors affecting maternal health and fetal development help explain this chronic disease risk decline (Fogel, 1999). Nutritional deficiencies could have affected maternal pelvic development and increased subsequent risks for cerebrovascular disease in the 1910 elderly Civil War veteran cohorts who were born between 1825 and 1844 (Costa, 1998). Maternal nutritional deficiency during pregnancy also can impact development of the pancreas and liver in the fetus, which may alter risks of diabetes

and heart disease as the child ages. These nutritional deficiencies were increasingly alleviated in the post-1840s birth cohorts.

Chronic disease risks were further altered in the early part of the twentieth century. For example, in the 1920s and 1930s changes in food preservation, thermal preparation, and storage affecting microbial food contaminants likely combined with changes in salt intake and water quality (e.g., reducing the prevalence of H. pylori infections) to alter the incidence of a wide range of chronic diseases, including stroke, hypertension, gastric and other cancers, and peptic ulcers (Fogel, 1999; Fogel and Costa, 1997). A similar pattern was found in Great Britain. Up to the 1940s the British centenarian population grew 1 percent per year (Perutz, 1998). After the 1940s (i.e., centenarians born after the 1840s) the growth rate was nearer 6 percent. Thus, in both Britain and the United States the major socioeconomic and nutritional changes appear to have affected the health and survival of post-1840 birth cohorts.

The national trends described above are accompanied by enormous variation within countries. County-specific analyses of historical trends in the adoption of primary prevention strategies and shifts in average socioeconomic status levels relative to those for a given state, or for the country at large, could provide a useful baseline for the formulation and targeting of future health promotion and disease prevention strategies.

Disability

Several influences on declining rates of disability among the elderly have been proposed. One suggestion is that these health improvements result from changes in the nature of work. Work has become less manually intensive and more cognitive over time, potentially delaying the onset of a range of adverse conditions, including musculoskeletal disorders and cardiovascular complications. In addition, exposure to dust and hazardous chemicals has declined. Preliminary evidence suggests that these changes may explain up to one-quarter of improvements in health for the elderly since the turn of the century (Costa, 1998), although no evidence exists for recent years.

The nature of work may matter in other ways as well. Work that is mentally stressful or not mentally challenging enough may lead to psychological stress that is manifest in physical disorder. For example, musculoskeletal disorders are more common in people with low job satisfaction, elevated psychophysiological stress reactions, and lack of opportunity to unwind, all of which are characteristic of repetitious work with short time cycles (Melin and Lundberg, 1997). Such findings are also reported in the Whitehall studies (Marmot et al., 1991; Marmot, 1994).

A second possibility is that health improvements result from improved

socioeconomic status (SES). SES has a large effect on individual health. As highlighted in Chapter 7, people with higher SES exhibit better health in a wide variety of settings and for a number of measures of health (Marmot, 1994). Furthermore, SES has changed substantially in recent years. Between 1970 and 1998, for example, the share of the elderly with more than a high school degree rose from 15 percent to 36 percent. Some evidence suggests that increased educational attainment of the elderly can explain part of the reduction in disability (Freedman and Martin, 1999). The existence of these socioeconomic factors in and of themselves does not constitute full explanations, but rather emphasizes the need to better understand the pathways through which they are linked to behavioral, environmental, and psychosocial variables and underlying neurophysiological mechanisms.

A third idea invokes more macro-level influences, namely, the impact of public health measures either in childhood or earlier in adulthood. Many infectious diseases affect health long after a person has passed the infectious stage (Costa, 1998), and there is recent evidence that nutrition as early as the fetal stage affects health in midlife and later (Barker, 1997a, b). Public health advances in the past century thus may have made important contributions to health among the elderly.

Many public health changes may also be linked with macro-level policies, such as the Surgeon General's report on smoking in 1964 (U.S. DHEW, 1964) or prohibitions against smoking in public places. Welfare reform can potentially be associated with health impacts on children. Regulations regarding the geographic placement and protective features of toxic waste dumps can influence the health of entire communities. Analyses of the impact of policies such as these are frequently undertaken by specialinterest groups. Monitoring such programs over long periods of time is, however, necessary to establish trends and deviations from them, as illustrated with the case of smoking and its much later disease sequelae (lung cancer, chronic bronchitis and emphysema, cardiovascular diseases; Warner, 2000). An important research priority is support for analyses of the health impacts of these policies. Linking them to the health of communities and of individuals is critically needed.

A final hypothesis concerning improvements in health is that medical advances, in the form of new therapies or prescription drugs, have played a major role. There clearly have been impressive medical advances in the past half century. Consider just one example: the treatment of severe coronary artery disease, which a half-century ago consisted largely of rest, hoping that less strain on the heart would reduce damage from the event. Today, therapy includes acute surgical advances such as cardiac catheterization, bypass surgery, and angioplasty; acute medical interventions such as thrombolysis; and less acute pharmaceutical innovations such as oral diuretics,

beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers. These advances have certainly contributed to reduced mortality and probably to reduced morbidity as well (Cutler et al., 1998).

Our ability to empirically differentiate among these various explanations of improved health outcomes has been significantly enhanced by recent developments in data sources. The availability of information from medical claims for large numbers of patients is one such advance. A decade ago medical records on representative groups of patients with particular conditions were not available. Today, Medicare and many private medical insurers in the United States keep such information and use it for this type of research. A second advance has been the implementation of longitudinal population surveys collecting information on socioeconomic status, early life resources, work conditions, family stress and support, physical and mental health, and medical care received that are also linked to earnings records from Social Security systems and medical care utilization from health insurers. Longitudinal data are essential because changing disability will be fully understood only by following the same people over time. The National Long-Term Care Survey, Health and Retirement Study (HRS), and Asset and Health Dynamics Survey (AHEAD) are three recent data sets having information that will be enormously important in this research. Other data sets could be designed (or relevant questions appended to existing surveys) to allow even more valuable research.

Communicable Diseases

The spread of STDs is influenced by three factors: (1) the average risk of infection per exposure, (2) the average rate of sexual partner change within the population, (3) and the average duration of the infectious period. The average duration of infection depends largely on availability and use of medical treatments. Medical treatment for STDs is generally poor in the United States (Holmes, 1994), with some evidence suggesting that overall lack of funding limits the ability of people to receive treatment.

Behavioral changes affecting the rate of sexual partner change are a second explanation for rising STD rates. The age of first sexual intercourse has been falling, rates of unsafe sex are rising, and the number of partners is increasing. The behavioral factors underlying these changes are less clear. One factor may be changes in social norms about appropriate sexual behavior. But other factors include economic circumstances such as the proportion of women working, physical circumstances such as the mix of rich and poor within cities, amount of crowding, and social programs such as the size of welfare benefits and the availability of medical treatments.

Understanding these behavioral and social determinants is central to reducing the spread of STDs. As emphasized in Chapter 6, the relation

between community variables and individual behavior is an extremely fruitful area for behavioral and social science research. Work on these areas will be greatly enhanced by ongoing monitoring of STDs and tuberculosis by the CDC. STD and tuberculosis rates can now be measured overall and at the level of particular communities, which will significantly increase our ability to understand the role of community factors in these health outcomes.

Changes in Child Health

Rates of infant mortality and low birth weight are each driven by a confluence of conditions that include low socioeconomic status; poor or no prenatal care; high-risk health behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking, and drug abuse by pregnant mothers); and chronic exposure to violence, poverty, and nonsupportive social networks. The teen birth rate is strongly correlated with the mother having grown up in an environment in which at least four of the following six conditions held: (1) as a child she was not living with two parents; (2) the household head was a high school dropout; (3) family income was below the poverty line; (4) the parent(s) did not have steady, full-time employment; (5) the family was receiving welfare benefits; and (6) she did not have health insurance (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 1999). All the above conditions vary dramatically by state and by county in the United States. For example, the percentage of children living in families that satisfy four or more of the above high-risk conditions for teen parenthood in 1996 varied from 7 percent in New Hampshire to 21 percent in Mississippi and 39 percent in the District of Columbia.

A more subtle understanding of pathways to low-birth-weight babies, teen parenthood, and infant mortality requires multilevel analyses linking community characteristics with individual histories. Much remains to be done in this area. The recent methodological advances and recommended research priorities for Chapter 6 can be expected to play a central role in future developments.

Turning to asthma, the most common chronic disease of childhood, a deep understanding of its causes still lies in the future. Several current National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiatives are aimed at addressing this knowledge gap. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) has an initiative aimed at specifying how genetic and environmental factors interact in the developing lung and lead to the onset of asthma. One study sponsored by NHLBI will examine the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying asthma's relationship with sleep and day-night events. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) has a new Environmental Genome Project that will study different populations in different parts of the country in order to examine how interaction between

the environment and certain genes leads to diseases like asthma. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and NIEHS are extending the Inner City Asthma Study, a study of children with asthma in seven U.S. cities that is examining the effects of interventions to reduce children's exposure to indoor allergens and improve communication with their primary care physicians. This investigation also involves collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency to evaluate the effects of exposure to indoor and outdoor pollutants. Integrating findings from these studies into a unified multilevel explanation of how asthma comes about, together with an assessment of preventive and curative interventions is an important future priority that will require integrative analyses of the sort described throughout this report.

HEALTH AND THE MACROECONOMY

The health status of the population may have macroeconomic effects in addition to affecting individual behavior. Empirically, countries that are less healthy are poorer than countries that are more healthy, and their incomes grow less rapidly. Thus, the income gap between more and less healthy countries is increasing over time. Recent research indicates that life expectancy is a powerful predictor of national income levels and subsequent economic growth (Fogel, 1999). Studies consistently find a strong effect of health on growth rates. Economic historians have concluded that perhaps 30 percent of the estimated per capita growth rate in Britain between 1780 and 1979 was a result of improvements in health and nutritional status (Fogel and Costa, 1997). That lies within the range of estimates produced by cross-country studies using data from the last 30-40 years (Jamison et al., 1998).

Health improvements also influence economic growth through their impact on demography. For example, in the 1940s rapid health improvements in East Asia provided a catalyst for demographic transition. An initial decline in infant and child mortality first dramatically increased the number of young people and then somewhat later prompted a fall in fertility rates. These asynchronous changes in mortality and fertility, which comprise the first phase of what is called the “demographic transition,” substantially altered East Asia's age distribution. After a time lag the working-age population began growing much faster than young dependents, temporarily creating a disproportionately high percentage of working-age adults. This bulge in the age structure of the population created an opportunity for increased economic growth (Bloom, 1999).

Over the past several years, the Pan American Health Organization/Inter-American Development Bank and the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean carried out a study to eluci-

date relations between investments in health, economic growth, and household productivity (WHO, 1999). Estimates based on data from Mexico throw some light on the time frame in which health affects economic indicators. High life expectancy at birth for males and females has an economic impact 0-5 years later. The impact of male life expectancy on the economy appears to be greater than that of female life expectancy, possibly because of the higher level of economic activity among males. The data suggest that for each additional year of life expectancy there will be an additional 1 percent increase in gross domestic product 15 years later. Similar findings were found for schooling.

Studies of this kind are in their infancy compared to other studies described in this report. Much remains to be done to link macro-level associations to the community and individual-level dynamics as discussed in Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 5, and Chapter 6. Understanding the reciprocal relationships between population health and the macroeconomy and their linkages to micro-level behavioral dynamics and intermediate-level community and social structural influences is a high-priority research direction. Indeed, it is precisely results such as those for Mexico, described above, that have implications for national economic policies leading to sustained commitments to investments in health. Providing clear evidence about linkages to community and individual levels can substantially strengthen the arguments for national commitments.

Health and the economy have long been linked by the practice of having children to ensure being cared for in old age. This is still true in many countries, but with public-sector innovations such as Social Security and medical care, the direct need for children as insurance has declined. In its place are issues of individual behavior (whether people live alone or with their children, whether they work or retire) and social questions about whether society can afford to provide care to an aging population.

The backdrop for much of the concern about changes in health is the strain that increasing length of life places on public programs in industrialized countries. The Social Security system in the United States is forecast to become insolvent around 2030, and Medicare is expected to be insolvent long before then. This situation, repeated throughout the developed world and in many developing countries, is made worse as population growth rates fall. Health improvements have hidden costs if they lead to difficulty financing public-sector programs for the elderly. However, recent evidence of rectangularization of survival curves, not only for mortality but for the age-specific onset of disability and chronic diseases (Vita et al., 1998), suggests that prevention strategies may be having positive countervailing effects.

Health improvements can play a substantial role in solving public-sector problems. People who develop a serious illness late in their working

life are more likely to retire early than are people who do not experience a serious illness at that age (Smith, 1999), which reduces their lifetime earnings. Adolescents who are diagnosed with depression are less likely to get a college degree than are those not so diagnosed (Berndt et al., 2000) and thus are likley to earn less over their lifetime. Advances in interventions that alleviate these health burdens could substantially reduce the public-sector financial burden. In any case, a central economic challenge facing the public sector is how to prepare for an aging society.

THE HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

The medical system is an important part of health. Indeed, public discussion about health focuses to an overwhelming degree on access to medical care. Understanding how the system operates and how well it works is therefore a central issue for behavioral and social research. We address three issues of concern in current and future evaluations of the health care system: (1) the effects of medical care on improving health, (2) the managed care debate, and (3) growing public interest in alternative medicine.

Effectiveness of Medical Care

Research shows mixed results regarding the value of the medical system. We illustrate these issues with medical care for the elderly, but the same issues apply to those who are not elderly, for example, asthma in children or disease transmission in teens and young adults. Some research highlights the positive effect of medical care on improving health. As noted above, one of the leading theories for reduced disability among the elderly is that such advances result from medical technology improvements. This view is widespread among biomedical researchers: medical advances, they believe, embodied in new technologies lead to significant health gains. Other research, however, highlights the apparently low return from additional medical spending. For example, Medicare spending varies by a factor of two among areas of the country, with no apparent differences in health outcomes (CECS, 1998). Research on heart attack patients shows that intensive procedures are used up to five times more frequently in the United States than in Canada, but mortality rates are the same in the two countries (Rouleau et al., 1993; Mark et al., 1994; Tu et al., 1997). Indeed, within the United States, people who live close to high-tech hospitals receive intensive services more frequently than people who live farther away from such hospitals, but again health outcomes are essentially the same (McClellan et al., 1994). The value of additional medical spending is therefore unclear and is a needed avenue for future research.

Several explanations have been proposed for the disparate or conflicting findings about whether medical care has high or relatively low returns. One hypothesis is that medical care is valuable but is often applied inappropriately. For example, areas that spend a lot on medical care may simply give the technology to more people than will benefit from it. Much evidence supports the view that medical care is frequently wasted. Studies of medical procedure use in the United States, for example, find that a significant number of patients receiving high-tech services should not receive them on the basis of published clinical studies (Chassin et al., 1987; Winslow et al., 1988a, b; Greenspan et al., 1988). Other evidence is less supportive, however, finding that rates of inappropriate procedure use are no greater in areas with high usage rates compared to areas with lower usage rates. Reconciling conflicting evidence about the value of medical care is an important priority for future research.

It also has been proposed that preventive care is used in inverse proportion to more intensive medical services, so that people not receiving intensive treatment still have good outcomes. This is claimed to explain the lack of outcome differences between the United States and Canada. Canada has more complete coverage for outpatient pharmaceuticals than does the United States. Increased use of pharmaceuticals may allow Canadians to live longer, offsetting the survival advantage that comes from more intensive procedure use in the United States.

The distinction between over-time and point-in-time analysis must also be considered in evaluating the effectiveness of medical care. Many studies that find that medical care has a high rate of return compare treatments at different points in time, that is, before and after a particular technology is available. For example, changes in the treatment of heart attacks during the 1980s are associated with large increases in survival (Cutler and Sheiner, 1998). The same is true for care of low-birth-weight infants between 1950 and 1990 (Cutler and Meara, 2000). In contrast, studies that find that medical care has a low rate of return generally look at the use of the same treatment in different localities at the same point in time. Differences in use at a point in time may be more wasteful than increased use over time.

An increasing number of cost-effectiveness analyses of preventive strategies and alternative therapies are appearing. For example, Trussell et al. (1997) analyzed the economic benefits of adolescent contraceptive use utilizing information from a national private payer data base and from the California Medicaid program. Their study estimated the costs of acquiring and using 11 contraceptive methods appropriate for adolescents, treating associated side effects, providing medical care related to an unintended pregnancy during contraceptive use, and treating sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and compared them with the costs of not using a contraceptive method. The average annual cost per adolescent at risk of unintended

pregnancy who uses no method of contraception is $1,267 ($1,079 for unintended pregnancy and $188 for STDs) in the private sector and $677 ($541 for unintended pregnancy and $137 for STDs) in the public sector. After one year of use private-sector savings from adolescent contraceptive use ranged from $308 for an implant designed to prevent ovulation to $946 for the male condom. Public-sector savings rose from $60 for the implant to $525 for the male condom. Both the use of male condoms with another method and the advance provision of backup emergency contraceptive pills provided additional savings.

Shifting to an example of the cost effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering therapies, Prosser et al. (2000) found that ratios varied according to different risk factors. Specifically, incremental cost effectiveness ratios were found for primary prevention with a low fat, low cholesterol diet (National Cholesterol Education Program step I), ranging from $1,900 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained to $500,000 per QALY depending on risk subgroup characteristics. Primary prevention with a statin (a cholesterol-lowering drug) compared with diet therapy was $54,000 per QALY to $1.4 million per QALY. Secondary prevention with a statin cost less than $50,000 per QALY for all risk subgroups. Primary prevention with a step I diet seems to be cost effective for most risk subgroups defined by age, sex, and the presence of additional risk factors. It may not be cost effective for otherwise healthy young women. In addition, primary prevention with a statin may not be cost effective for younger men and women with few risk factors, given the option of secondary prevention and of primary prevention in older age groups. Secondary prevention with a statin seems to be cost effective for all risk subgroups and is cost saving for some high-risk subgroups.

As a further illustration, an economic evaluation was conducted alongside a randomized controlled trial of two lifestyle interventions (e.g., education and video to assess risk factors, program plan for risk factor behavior change) and a routine care (control) group to assess cost effectiveness for patients with risk factors for cardiovascular disease (Salkeld et al., 1997). The cost per QALY for males ranged from $152,000 to $204,000. Further analysis suggested that a program targeted at high-risk males would cost $30,000 per QALY. The lifestyle interventions had no significant effect on cardiovascular risk factors when compared to routine patient care. There remains insufficient evidence that lifestyle programs conducted in general practice are effective. Resources for general-practice-based lifestyle programs may be better spent on high-risk patients who are contemplating changes in risk factor behaviors. Alternatively, the extensive literature on the economics of coronary heart disease prevention (Brown and Garber, 1998) suggests that many programs (e.g., exercise, smoking cessation, de-

tection and treatment of hypertension, cholesterol reduction) are highly cost effective.

While these examples are illustrative of the kinds of studies needed on a wider scale, it is important to underscore that such inquiries can have substantial impact on the quality of care provided by a diverse range of practitioners. In addition, errors in specification of therapeutic programs, mistakes made during surgical procedures, improper diagnoses, and faulty laboratory procedures are being documented on an increasingly broad scale. Such lines of inquiry are important for understanding the behavior of health care providers as a function of economic and organizational constraints placed on them. It will be equally important to turn solid research findings into improved practices. This will require effective communication and ongoing dialogue between the research community and practitioners. Cultural factors also play a prominent role here, since patients of different ethnic backgrounds approach—or do not approach—health care providers with very diverse views of health and wellness (Kleinman, 1981, 1989). Also important for the future will be analyses of data on medical treatments matched to health outcomes. Such data are now becoming widely available through Medicare and large insurers.

The Managed Care Debate

Public concern about managed care is intense, as recent legislative efforts to enact a patients' bill of rights attest. Research about how managed care actually affects medical practice, however, is limited. Changes in insurance coverage for nonelderly Americans between 1980 and 1996 were dramatic. In 1980, 92 percent of the population had traditional indemnity insurance, with 8 percent in health maintenance organizations (HMOs). In 1996 only 3 percent of the population remained in unmanaged fee-for-service plans. An additional 22 percent were in managed fee-for-service plans. The bulk of the population was enrolled in various types of managed care programs, including traditional HMOs, preferred-provider organizations (PPOs), and point-of-service plans (POSs). The spread of managed care is largely responsible for the reduced rate of growth of medical spending in the 1990s (Cutler and Sheiner, 1998).

This trend has provoked fundamental questions. How does managed care save money: by restricting the number of services provided or by cutting payments for services? That is, managed care might affect the delivery of medical care in two ways: by altering the access rules (determining which people have access to medical providers) and the payment rules (determining reimbursement to providers). People with managed care insurance typically have more restrictive access to providers and high-tech care than do people in traditional indemnity insurance. On the other hand,

people with managed care insurance generally have lower costs than do those with indemnity insurance.

The central issue is how health outcomes are affected by managed care. A second issue is whether the rise of managed care affects the diffusion of medical technology and whether that will be good or bad. Understanding the full incentives of managed care is difficult and requires the participation of both economic and medical expertise, for example, in understanding exactly how physicians are paid and what services they are able to provide. Sociological and psychological input is necessary as well. For example, physicians treated as employees of a managed care insurer may behave differently than physicians who see themselves as running their own practice. The degree to which managed care affects physician practice may depend on how it changes physicians' perceptions of their role in the medical system as much as it changes their actual ability to provide certain services. Research has yet to explore this issue.

Managed care might also have a direct effect on the extent to which providers acquire and use particular technologies. Several recent papers argue that managed care has reduced the diffusion of hospital-based technologies, including diagnostic scanners and some surgical procedures (Cutler and Sheiner, 1998; Baker and Spetz, 1999). If such changes in access translate into change in utilization, it could have important implications for the long-term value of the medical sector. Research on this issue is just beginning as well.

In summary, the phenomenal change in the medical system encompassed by managed care, coupled with the availability of rich sources of data, make this topic a prime candidate for future research. Understanding the economic and health consequences of managed care has great import for informing public policy pertaining to the health care system.

Alternative Medicine Therapies

A large and expanding component of the U.S. health care system involves alternative medicine therapies, functionally defined as interventions neither taught widely in medical schools nor generally available in U.S. hospitals (Eisenberg et al., 1993). In 1990 a national survey of alternative medicine prevalence, costs, and patterns of use demonstrated that alternative medicine has a substantial presence in the U.S. health care system. Since that time, an increasing number of insurers and managed care organizations have offered alternative medicine programs and benefits. Correlatively, the majority of U.S. medical schools now offer courses on alternative medicine (Wetzel et al., 1998; Eisenberg et al., 1998).

In a follow-up national survey conducted in 1997 (Eisenberg et al., 1998), data were assembled that allowed for quantitative assessment of

trends in alternative medicine use over that time period. Use of at least one of 16 alternative therapies investigated increased from 8 percent in 1990 to 42.1 percent in 1997. The therapies increasing the most included herbal medicine, massage, megavitamins, self-help groups, folk remedies, energy healing, and homeopathy. In both the 1990 and 1997 surveys alternative therapies were used most frequently for chronic conditions, including back problems, anxiety, depression, and headaches. The percentage of users paying entirely out of pocket for services provided by alternative medicine practitioners did not change significantly between 1990 (64.0 percent) and 1997 (58.3 percent). Extrapolations to the U.S. population suggest a 47.3 percent increase in total visits to alternative medicine practitioners, from 427 million in 1990 to 629 million in 1997, thereby exceeding total visits to all U.S. primary care physicians. An estimated 15 million adults in 1997 took prescription medications concurrently with herbal remedies and/or high-dose vitamins (18.4 percent of all prescription users). Estimated expenditures for alternative medicine professional services increased 45.2 percent between 1990 and 1997 and were conservatively estimated at $21.2 billion in 1997, with at least $12.2 billion paid out of pocket. This exceeds the 1997 out-of-pocket expenditures for all U.S. hospitalizations. Total 1997 out-of-pocket expenditures relating to alternative therapies were conservatively estimated at $27 billion, which is comparable to the projected 1997 out-of-pocket expenditures for all U.S. physician services.

The large economic impact of alternative medicine clearly demands research attention. Specifically, substantial resources should be devoted to clinical and integrated biological and social science research to provide rigorous understanding of the role of these interventions in the health of the U.S. population. This is important for establishing the credibility of claims for alternative medicine therapies. Part of this line of inquiry should include research on why placebos sometimes work and for whom. More generally, the broad area of mind/body relationships and their neurobiological underpinnings represent a vast research opportunity for the future. A useful example of the kind of knowledge development and synthesis that are needed is the elaborate study of meditation and neurobiology by Austin (1998). The new NIH trans-institute initiative that recently established five mind/body centers around the United States constitutes a further important step in this direction.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS IN POPULATION SURVEYS

Several sources of data and methodologies will be essential in addressing the agendas described above. Perhaps the most basic need is for enhanced longitudinal population-level surveys. Such surveys should be enhanced in three ways:

-

They need to be linked to administrative records on the receipt of medical care and on work histories. Such linkage is vital because individuals will not recall all of the medical care they have received nor their earnings records.

-

Surveys need to be supplemented with community-level variables to determine how the social and economic environments affect individual behavior.

-

They need to have basic biological markers. Incorporating indicators of cumulative physiological risk (e.g., allostatic load) as standard components of longitudinal survey protocols would provide a basis for the integrative analyses recommended throughout this report. Augmenting longitudinal surveys with physical health examinations would be of enormous value, as the Framingham Study has shown.

Data from medical systems are also essential. Health insurers in the United States and other countries have access to unparalleled data on medical treatments and outcomes. These data can be used to study the value of the medical system. They can also address questions about behavior and community-level variables because they often contain detailed information on health conditions and medical treatments at the community level. Finally, we stress the role for international comparative work in answering the full range of population health questions discussed in this chapter. Economic, social, and medical systems differ greatly across countries, and thus international work is a natural laboratory for analysis.

RECOMMENDATIONS

We urge NIH to invest new resources in research to identify linkages between population health trends and the behavioral, environmental, and psychosocial factors emphasized in preceding chapters. Priority should be given to the following topics:

-

multilevel analyses necessary to advance rigorous explanations for the observed dynamics of the health of populations, giving particular emphasis to behavioral risk and protective factors and to psychosocial and environmental influences on aggregate-level health changes;

-

development of projection methodologies to provide defensible scenarios of how health changes will affect society in the future;

-

continue and expand multi-institute support of research on child health, particularly asthma and its costs, both economic (e.g., parental absence from work) and social (e.g., family burden, child development);

-

increase support for research on the reciprocal relationships between

-

population health and the macroeconomy , together with linkages to community and individual-level dynamics as discussed in prior chapters;

-

develop new initiatives to investigate the conflicting findings about whether medical care has high or low returns for whom , when , and how . Importantly , data on medical treatments must be matched to health outcomes;

-

increase support for research on the economic and health costs or benefits of managed care (of central importance are studies that clarify how health outcomes are affected by managed care);

-

establish new trans-institute priorities to evaluate the effectiveness of alternative medicine therapies as well as to clarify their economic impact .

REFERENCES

Annie E. Casey Foundation . 1999 Kids Count Data Book, 1999 ( Baltimore : Annie E. Casey Foundation ).

Austin J. 1998 Zen and the Brain( Cambridge MA : MIT Press ).

Baker L , Spetz J. 1999 “Managed care and medical technology growth” NBER Working Paper 6894 ( Cambridge MA : National Bureau of Economic Research ).

Barker DJ. 1997a “The fetal origins of coronary heart disease” Acta Paediatrica422/suppl. : 78-82 .

Barker DJ. 1997b “Maternal nutrition, fetal nutrition and disease in later life” Nutrition 13/9 : 807-13 .

Berndt ER , Koran LM , Finkelstein SN , Gelenberg AJ , Kornstein SG , Miller IW , Thase ME , Trapp GM , Keller MB. 2000 “Lost human capital from early-onset chronic depression” American Journal of Psychiatry 157/6 : 940-947 .

Bloom BR. 1999 “The future of public health” Nature 402/suppl. 2 December : C63-C64 .

Brown AD , Garber AM. 1998 “Cost effectiveness of coronary heart disease prevention strategies in adults” Pharmacoeconomics 14/1 : 27-48 .

CECS (Center for Evaluative Clinical Sciences) , Dartmouth Medical School . 1998 Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care ( Chicago : American Hospital Publishing ).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) . 1999a “Progress toward the elimination of tuberculosis—United States, 1998” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report48/33 : 732-736 .

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) . 1999b Tracking the Hidden Epidemics: Trends in the STD Epidemics in the United States ( Atlanta : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) . 1999c “Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1997” MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report48 : 993-996 .

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) . 1999d Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 1998( Atlanta : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ).

Chassin MR , Kosecoff J , Park RE , Winslow CM , Kahn KL , Merrick NJ , Keesey J , Fink A , Solomon DH , Brook RH. 1987 “Does inappropriate use explain geographic variations in the use of health care services? A study of three procedures” Journal of the American Medical Association 258/18 : 2533-2537 .

Costa DL. 1998 “Understanding the twentieth century decline in chronic conditions among older men” Working Paper 6859 ( Cambridge MA : National Bureau of Economic Research ) .

Cutler D , Meara E. 2000 “The technology of birth: Is it worth it?” in Garber A (ed.). Frontiers in Health Policy Research, Volume III( Cambridge MA : MIT Press ).

Cutler DM , Sheiner L. 1998 “Managed care and the growth of medical expenditures” in Garber A (ed.). Frontiers in Health Policy Research, Volume I ( Cambridge MA : MIT Press ).

Cutler DM , McClellan M , Remler D , Newhouse JP. 1998 “Are medical prices declining? Evidence from heart attack treatments ” Quarterly Journal of Economics 133/4 : 9911024 .

Daszak P , Cunningham AA , Hyatt AD. 2000 “Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife—Threats to biodiversity and human health” Science : 443-449 .

Eisenberg DM , Kessler RC , Foster C , Norlock FE , Calkins DR , Delbanco TL. 1993 “Unconventional medicine in the United States Prevalence , costs , and patterns of use” New England Journal of Medicine 328/4 : 246-252 .

Eisenberg DM , Davis RB , Ettner SL , Appel S , Wilkey S , Van Rompay M , Kessler RC. 1998 “Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a follow-up national survey” Journal of the American Medical Association 280/18 : 1569-1575 .

Eng TR , Butler WT. 1997 The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Diseases ( Washington DC : National Academy Press ).

Fogel RW. 1999 “Catching up with the Economy” The American Economic Review89/1 : 1-21 .

Fogel RW , Costa DL. 1997 “A theory of technophysio evolution, with some implications for forecasting population, health care costs, and pension costs” Demography 34/1 : 49-66 .

Freedman VA , Martin LG. 1998 “Understanding trends in functional limitations among older Americans ” American Journal of Public Health 88/10 : 1457-1462 .

Freedman VA , Martin LG. 1999 “The role of education in explaining and forecasting trends in functional limitations among older Americans” Demography 36/4 : 461-473 .

Greenspan AM , Kay HR , Berger BC , Greenberg RM , Greenspon AJ , Gaughan MJ. 1988 “Incidence of unwarranted implantation of permanent cardiac pacemakers in a large medical population” New England Journal of Medicine 318/13 : .

Hill JO , Peters JC. 1998 “Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic” Science 280 : 1371-1374 .

Holmberg SD. 1996 “The estimated prevalence and incidence of HIV in 96 large US metropolitan areas” American Journal of Public Health 86/5 : 642-654 .

Holmes KK. 1994 “Human ecology and behavior and sexually transmitted bacterial infections ” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America91/7 : 2448-2455 .

Jacobzone S. 2000 “Coping with aging: International challenges” Health Affairs 19/3 : 213-225 .

Jamison DT , Lau LJ , Wang J. 1998 “Health's contribution to economic growth, 1965-1990” in Health, Health Policy and Economic Outcomes: Final Report Health and Development Satellite , WHO Director-General Transition Team( Geneva : World Health Organization ): 61-80 .

Kaiser Family Foundation . 1998 Sexually Transmitted Diseases in America: How Many Cases and at What Cost? ( Menlo Park : Kaiser Family Foundation ).

Kleinman A. 1981 Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture( Berkeley : University of California Press ).

Kleinman A. 1989 The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition . ( New York : Basic Books ).

Lederberg J , Shope RE , Oakes SC Jr. (eds.). 1992 Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States ( Washington DC : ).

Lee I , Paffenbarger RS , Hsieh C. 1991 “Physical activity and risk of developing colorectal cancer among college alumni” Journal of National Cancer Institute 83 : 1324-1329 .

Manson JE , Tosteson H , Ridker PM , Satterfield S , Hebert P , O'Connor GT , Buring JE , Hennekens CH. 1992 “The primary prevention of myocardial infarction” New England Journal of Medicine 326/21 : 1406-1416 .

Manton KG , Corder L , Stallard E. 1997 “Chronic disability trends in elderly United States populations: 1982-1994 ” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94/6 : 2593-2598 .

Mark DB , Naylor CD , Hlatky MA , Califf RM , Topol EJ , Granger CB , Knight JD , Nelson CL , Lee KL , Clapp-Channing NE , Sutherland W , Pilote L , Armstrong PW. 1994 “Use of medical resources and quality of life after acute myocardial infarction in Canada and the United States” New England Journal of Medicine 331/17 : 1130-1135 .

Marmot MG. 1994 “Social differentials in health within and between populations” Daedalus 123/4 : 197-216 .