1

Introduction

The Social Security Administration (SSA) asked the National Research Council (NRC) to survey published research on assessment of hearing and the auditory demands of everyday life and to advise them whether the process of determining eligibility for Social Security disability benefits for persons with hearing loss could be improved. The SSA also requested recommendations for a research agenda to address unanswered questions in these areas. The Committee on Disability Determination for Individuals with Hearing Impairment1 (the committee) was charged with answering these questions.

KEY ISSUES

According to the committee’s scope of work, the key issue is whether or not standardized tests exist or can be developed “that provide adequate prediction of real-world performance capacities to reflect individuals’ auditory abilities and disabilities in normal life situations with average background noise.” Such tests would need to be valid, reliable, well-standardized, and “simple and inexpensive to administer in a standard physician’s or audiologist’s office setting.”

The scope of work went on to list several important subsidiary issues, each of which is discussed briefly in this section and extensively in the report:

-

Current SSA procedures use “subjective” tests that present tones and words through headphones, relying on individuals’ ability and willingness to report what they hear. Could objective (physiological) measures of auditory function perform better?

-

The validity and reliability of the tests currently used by SSA, as well as their criterion values (“cutoff” levels), may not be optimal. Could other tests (including tests that include background noise) or other criterion values perform better?

-

At present, as stated in the committee’s scope of work, “SSA does not give clear guidance about testing with and/or without hearing aids or cochlear implants for those who use such devices.” Should aided testing be recommended, and, if so, how should such tests be conducted?

-

Current procedures attempt to assess only abilities to detect simple tones and to understand speech. Since identification of nonspeech sounds and sound localization are required in some jobs, should these auditory abilities be tested as part of the SSA disability process?

-

Can research using measures of health-related quality of life help to determine which auditory skills and losses have the greatest impact on the lives of persons with hearing loss?

-

Can performance deficits resulting from hearing loss be separated from those resulting from nonauditory (e.g., cognitive, linguistic) factors?

Most of these questions have to be addressed separately for adults and children, for two reasons. First, small children sometimes require different testing methods than adults, because of their relative inability to participate in some hearing tasks. Second, adults and children must meet very different standards for eligibility for SSA disability programs. For adults, SSA disability is defined as “inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.” For children, in contrast, any stable impairment that is “marked or extreme” may result in eligibility, and SSA regulations explicitly define this statistically rather than in terms of inability to successfully perform the learning tasks of childhood. “Marked” limitation is “the equivalent of the functioning we would expect on standardized testing with scores that are at least two, but less than three, standard deviations below the mean,” whereas “extreme” limitation begins at three standard deviations below normal. A child is considered to meet the listings if he or she has extreme

impairment in one functional domain or marked impairments in two of six functional domains.

For both adults and children, determination of eligibility is a multi-step process. Step 1 deals with financial eligibility, and Step 2 requires proof of a physical or mental impairment that at least “significantly limits” some activities and is expected to last at least 12 months or to result in death. Step 3 applies “medical listing” criteria to the applicant’s impairment; if these are met or exceeded, the claimant is found eligible. Adult applicants not found eligible at Step 3 may still receive eligibility if, after consideration of their age, education, and work experience, as well as their residual capacities, they are found to be unable to perform either the work they have done in the past (Step 4) or any other work in the U.S. economy (Step 5). An additional step is also available for children who fail to meet the medical listing criteria in Step 3. This report addresses the hearing testing that is used in Steps 3-5.

Nature of Current Measures

For both adults and children, SSA now relies on two clinical tests, described in detail in Chapter 3, that are widely used in clinical practice. One of them, pure-tone audiometry, is also well standardized: four American National Standards (American National Standards Institute, 1996, 1997, 2002a, 2003) specify the conditions and methods of testing. The other, speech discrimination (presumably using monosyllabic words, although the SSA regulations do not specify this), is not standardized by the American National Standards Institute, by any national professional association, or by SSA. Speech discrimination tests done by different audiologists frequently differ in several ways that affect the difficulty and the reliability of the test: the word lists chosen, the number of words presented, the intensity (loudness) of the words, male versus female speaker, the use of live voice versus recorded word lists, and whether people who use hearing aids or cochlear implants are tested with or without their devices. Other types of speech tests, using sentences instead of words, with or without background noise, are discussed in Chapter 3; none of these is widely used in the United States at present.

Pure-tone audiometry is a test of auditory sensitivity. The softest sound that can be heard (threshold) is recorded for each ear, for tones ranging from low frequencies (250 Hz is approximately middle C) to high frequencies (8000 Hz is one octave above the highest note on the piano keyboard). A graph of threshold versus frequency is called an audiogram. Audiometry measures the ability to detect simple sounds, and thresholds for the frequencies most important for speech communication correlate approximately with the level of difficulty people experience in daily life

(e.g., 25 to 40 dB = “mild” hearing loss, 40 to 55 dB = “moderate” hearing loss, etc.; see Table 3-1 for complete classification of hearing loss). Audiometry does not directly measure other auditory abilities, such as sound recognition, sound localization, and speech recognition. Because of this limitation, scientists and clinicians have sought better ways to assess real-world hearing abilities for over 60 years.

At the beginning of World War II, some otologists thought that speech tests should be used instead of audiometry to determine fitness for duty, but the prevailing expert opinion was that “speech tests are very unreliable” (Fowler, 1941, p. 941). In the 1950s, a committee of the American Medical Association (AMA) hoped that valid and reliable tests of everyday speech understanding would soon be available, ending what they believed to be a “temporary” reliance on audiometric methods of estimating the impact of hearing loss (American Medical Association, 1955). For reasons we discuss below, this never happened.

The AMA continues to recommend pure-tone audiometry for the evaluation of hearing impairment (American Medical Association, 2001), and no state or federal agency uses speech tests to determine eligibility for workers’ compensation benefits (the Veterans Administration uses both pure tones and speech for eligibility for disability benefits, but has an alternate procedure using only pure-tone audiometry for cases in which speech tests are deemed unreliable). As in the United States, compensation schemes in Canada (Alberti, 1993), Ireland (Hone et al., 2003), and Australia (Rickards et al., 1996) use pure-tone audiometry. Some programs in the United Kingdom also use pure-tone audiometry (King et al., 1992), but others do not (Niven-Jenkins, 2004). Members of the committee do not know the methods used in other countries.

For a hearing disability to be determined, the SSA medical listing criteria for adults require, for the better ear, either:

-

Pure-tone average (PTA) air conduction threshold, for 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz, (PTA 512)2 of 90 dB hearing level or greater, with corresponding bone conduction thresholds, or

-

Speech discrimination score of 40 percent or less, at a level “sufficient to ascertain maximum discrimination ability.”

The committee was unable to discover the history or rationale for these criteria. In addition, while the references to the better ear and to “maximum discrimination ability” suggest tests done using earphones,

without the use of cochlear implants or hearing aids, the medical listings are ambiguous. They mandate neither testing with earphones nor aided testing, but they refer to “hearing not restorable by a hearing aid,” and a separate SSA manual (Social Security Administration, 2003b) states that aided testing should be done for individuals who use hearing aids or when there is a “probability that the hearing level can be improved by a hearing aid.” The committee has been advised by SSA staff that this policy is generally disregarded, and that when the results of aided testing have been the sole basis for denial of benefits, appeals to administrative judges have usually been successful. Thus, in this report, we assume that the current medical listings (for both adults and children) refer to unaided hearing tests, performed using earphones.

The audiometric criterion level (PTA = 90 dB or worse) is equivalent to “profound” hearing loss in ordinary clinical terminology. People with hearing loss of this magnitude almost always consider themselves “deaf.” If the goal is to predict “inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity,” the 90 dB criterion will produce both false positive errors (granting eligibility to people who can work) and false negative errors (denying eligibility to people who cannot work). In the SSA process false negative errors in Step 3 can be reversed in Steps 4 and 5 (i.e., the applicant may succeed in obtaining eligibility based on factors including age and experience), while false positive errors in Step 3 are generally irreversible.

Many—perhaps most—adults with severe to profound hearing loss do work, and some who use hearing aids and cochlear implants work in jobs that require frequent speech communication (some of those will be false positives, if the 90 dB criterion is used). Conversely, many people are genuinely disabled by lesser degrees of hearing loss (false negatives). For example, even with well-fitted hearing aids, many people with PTA between 80 and 90 dB understand fewer than 60 percent of words in sentences at conversational levels (Flynn et al., 1998). They would probably have difficulty in many tasks requiring hearing without the assistance of vision, such as using the telephone. Such a person whose job had always required telephone work, and whose age and experience realistically precluded other work, might be unable to work but would fail to meet the 90 dB criterion of Step 3. This person could still be found eligible in Steps 4 and 5.

The committee is unaware of any data, from SSA or other sources, that attempt to quantify the problem of false positive and false negative errors using the current medical listing criteria. Such data, if available, could suggest changes in those criteria. For example, if the percentage of people who reenter the workforce after failing to meet medical listing criteria were found to drop sharply for PTA worse than 70 or 80 dB, this might support a lower (more liberal) PTA criterion.

By requiring absent bone conduction thresholds at the limits of the audiometer, SSA limits the medical listings to hearing loss that is purely or predominantly sensorineural (due to inner ear disorder), rather than a “mixed” hearing loss that could include a large conductive (outer or middle ear) component. The rationale for this requirement is unstated. While it is generally accepted that persons with conductive hearing losses usually function better with hearing aids than people with purely sensorineural hearing losses of the same severity, this may not be true for people with profound mixed hearing losses.

The speech discrimination criterion for adults (40 percent or worse for monosyllables) is more difficult to relate to everyday difficulties. It has long been known that the level “at which 50 percent [of monosyllables] is correctly understood is a little above the level at which we can easily understand ordinary connected speech” (Davis, 1960, p. 191). According to American National Standard ANSI S3.5 (2002b), a score of 40 percent for monosyllables predicts that words in familiar sentences will be understood with greater than 90 percent accuracy, while words in novel sentences will be understood with about 75 percent accuracy (without being able to see the speaker’s face). Thus, a 40 percent score for isolated monosyllables would imply at least some difficulty in everyday life for most persons (for example, using the telephone), but not necessarily inability to communicate by speech at work, especially in situations in which the listener can see the speaker’s face. Speech discrimination is an important part of the current criteria, because many applicants with PTA much better than 90 dB will have maximum speech discrimination scores (under earphones) below 40 percent. Dubno et al. (1995) have suggested that people with 70 dB PTA have mean speech discrimination scores of 50 percent, and 5 percent of them will have scores below 25 percent.

The SSA speech discrimination listing, like the audiometric listing, will produce both false positive and false negative errors. In addition, speech discrimination scores are subject to additional sources of error: increased problems with reliability, validity, exaggeration (discussed in the following paragraphs), and reliance on a subject’s knowledge of the language used in the test (see nonauditory factors below).

Because of lack of standardization, a 40 percent score from one audiologist is not equivalent to a 40 percent score in another office, where the word list, the voice, and the presentation level may all be different. Even under identical conditions, test-retest reliability is worse for speech discrimination tests than for pure-tone audiometry. The 95 percent confidence interval for a 40 percent score is quite wide: 26 to 55 percent (Thornton and Raffin, 1978). This means that if a claimant who scored 40 percent on a single test were subjected to a large number of test repetitions and that person’s “true score” is defined as the average of all the

individual scores, one can be pretty sure that the true score is between 26 and 55 percent. This assumes the use of a 50-word list for each test (the confidence interval would be even wider when using the 25-word lists typically used in clinical testing).

The validity of monosyllable speech discrimination tests given in quiet, often at levels considerably above the levels of conversational speech, has been severely criticized because most real-world speech involves sentences, with variable types and amounts of background noise. Indeed, reviews of studies comparing pure-tone audiometry with speech perception tests as predictors of subjects’ self-report of hearing difficulties have usually found pure-tone audiometry to be superior (Dobie and Sakai, 2001; Hardick et al., 1980; King et al., 1992). (Measures of health-related quality of life could in principle be used instead of self-report of hearing difficulty to validate different types of hearing tests; this potential approach is discussed in Chapter 6.)

It is not yet clear whether other types of speech tests, such as those using sentences, perform better than monosyllable tests or pure-tone tests as predictors of real-world difficulties. Simply substituting sentences for words only begins to address the range of real-world speech communication, which involves many other variables, such as:

-

Background noises of different types, levels, and locations;

-

Speech that varies in complexity, familiarity, level, speed, and even frequency composition (e.g., shouted speech contains relatively more high-frequency energy than spoken speech);

-

Distortion introduced by such transmission systems as two-way radios or by reverberation in enclosed environments;

-

Opportunity to request repeats of misheard words or sentences;

-

Different speakers (men, women, children, different accents, etc.);

-

Opportunity to see the speaker’s face;

-

Linguistic and cognitive factors for speaker and listener (see nonauditory factors below);

-

Need to respond quickly; and

-

Duration of the task (need for auditory “stamina”).

No published speech test has attempted to capture variations in even half of these factors. As long as 55 years ago, Davis and his colleagues (Davis, 1948) developed a battery of speech tests (the Social Adequacy Index), given at three different intensity levels, in an attempt to capture at least some of this range, but this strategy was abandoned because the tests took too long. Other tests, described in Chapter 3, have used sentences of varying difficulty or presented background noise—of a single type—at different levels. But valid and reliable simulation and prediction

of real-world performance with speech tests of reasonable length remains a challenge (Gatehouse, 1998).

Speech tests are also more susceptible to exaggeration than puretone tests, an important consideration for medical-legal testing (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 1981). Audiologists have many methods to detect exaggeration on pure-tone audiometry, and when behavioral tests cannot be trusted, evoked potentials can be used to estimate the pure-tone audiogram. No such tools have been described that can either detect exaggeration on speech discrimination tests or estimate “true” performance for an uncooperative subject.

The SSA medical listings for children use the same tests as for adults, but with different criteria for pure-tone audiometry. The average threshold for 500, 1000, 2000, and 3000 Hz (PTA 5123) is used, instead of the three-frequency average used for adults. For children below the age of 5, the better-ear criterion is 40 dB; from age 5 to 17, the criterion is 70 dB, unless there is a coexistent speech or language disorder (then it is 40 dB, as for younger children). The speech discrimination criterion, which is applied only to children age 5 and older, is 40 percent, as for adults. The committee was unable to discover the history or rationale behind these criteria.

The committee noted the SSA’s interest in knowing whether “objective” hearing tests could replace or supplement the behavioral tests that now are used.3 These tests (otoacoustic emissions and evoked potentials), discussed in Chapter 3, are extremely useful for such purposes as newborn hearing screening and determining the part of the auditory system that is affected in an individual. For example, they are essential when making a diagnosis of auditory neuropathy. They do not help to estimate the impact of hearing loss in everyday life for an adult who is able and willing to cooperate and to provide valid results in behavioral testing. For small children and uncooperative adults, however, evoked potential tests may provide the best or only available information regarding auditory sensitivity; in such cases, evoked potential threshold estimates can be used in place of unobtainable or unreliable behavioral thresholds.

Hearing-Critical Work and Everyday Activities

Each of the auditory abilities described in Chapter 2 is important in some workplaces. Many workers need to be able to detect simple sounds

such as back-up beepers and fire alarms. Knowledge of a person’s audiogram, combined with the intensity and frequency content of both a warning signal and any interfering background noise, will usually permit a valid prediction of that person’s ability to hear the warning signal (International Organization for Standardization, 2003). Other workers need to discriminate one sound from another (for example, normal versus abnormal functioning of a piece of equipment) or to localize sounds that may come from different directions. No tests of sound localization or discrimination of nonspeech sounds are in common clinical use.

Most workers need to communicate using speech. Speech communication on the job is at least as variable in difficulty as everyday speech. A lawyer listening to a soft-spoken witness or to several angry people talking at once is performing very different tasks from an air traffic controller guiding airplanes to their runways. Entry requirements for many jobs (e.g., as set by the Department of Defense, the Department of Transportation, and many local police and fire departments) require relatively good hearing, based on pure-tone audiometry. In general, these criteria appear to have been based on expert judgment rather than on evidence relating audiometry to job performance, and these entry criteria vary widely across agencies, even for jobs that are substantially identical. In workplaces covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, if speech communication is not an “essential function” of the job, “reasonable accommodation” for hearing-impaired persons may include substitution by email, text messaging, occasional use of sign translators for meetings, etc.

Despite the obvious importance of hearing in most jobs, hearing loss—even when severe or profound—is far from an absolute impediment to employment. Most adults ages 18 to 44 (and almost half of those ages 45 to 64) with severe to profound hearing loss are employed (Blanchfield et al., 2001). Similarly, 75 percent of working-age men who described themselves as “deaf in both ears” on the National Health Interview Survey were employed (Houtenville, 2002). Some of these people derive significant benefit from hearing aids and cochlear implants, enabling them to do jobs that require some hearing abilities. Others work in jobs that do not require hearing ability at all or that have been modified to accommodate their disabilities. It seems unlikely that there is any measurable degree of hearing loss that can reliably predict the “inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity” without taking into account a person’s age, education, and work experience.

Prosthetic Devices

Until the widespread availability of cochlear implants in the 1980s, persons with hearing loss had to function either unaided or with conven-

tional hearing aids, which are essentially amplifiers that make some inaudible sounds audible. The AMA’s Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment (American Medical Association, 2001) and almost all state and federal workers’ compensation programs (including the Veterans Administration) base estimation of the impact of hearing loss entirely on unaided testing. While this approach ignores the benefit of hearing aids, it preserves at least a reasonable ranking of severity across individuals. For example, three patients with mild, moderate, and severe hearing loss (unaided) would be expected to have the same relative performance ranking with hearing aids: the patient with mild hearing loss would probably have the best aided performance, and the patient with severe hearing loss would have the poorest aided performance. An exception to this general practice is the California workers’ compensation system, which combines aided and unaided tone thresholds into an overall estimate of severity of hearing loss.

Some decades ago, there was considerable enthusiasm for aided speech testing (in a sound field rather than under headphones) as a method of selecting the “best” hearing aid for an individual or estimating the impact of (aided) hearing loss on that person. That enthusiasm has waned considerably. Dempsey (1994, p. 731) has stated “The feeling of a significant number of researchers today is that no particular speech test or speech stimulus has been shown to be a reliable or valid predictor of performance with a hearing aid.” Of dispensing audiologists who responded to a recent mailed survey, only about half used aided speech discrimination tests at all; of those who used such tests, most used monosyllables in quiet. Only 3 percent of respondents used sentence tests (Mueller, 2001).

Cochlear implants required a return to aided sound field speech testing, because neither aided nor unaided pure-tone thresholds could predict the degree of benefit an individual received from a cochlear implant. A cochlear implant’s external sound processor can be adjusted to produce aided pure-tone thresholds at any desired level, but these thresholds are unrelated to the ability to understand speech, which is extremely variable across individuals (Bilger, 1977; Rizer et al., 1988). Only by self-report or aided speech testing can the performance of different cochlear implant patients or devices be distinguished from one another.

Linguistic, Cognitive, and Other Nonauditory Factors

All behavioral tests, including even pure-tone audiometry, test more than just the ear, requiring an alert and cooperative subject who is able to respond when sounds are heard. When speech sounds are presented, the subject must also possess some knowledge of spoken language in general

and of the language being spoken. The importance of this knowledge increases as the type of speech sound moves from nonsense syllables to single words to sentences.

Native speakers find sentences much easier than single words or nonsense syllables, because they can use multiple types of cues to “fill in the blanks” when words and sounds have been misheard. One type of cue involves familiarity with individual speech sounds (phonemes); every language has a limited set of phonemes (English has about 40) selected from a much larger set represented in the world’s languages (the International Phonetic Alphabet has over 100 symbols, which can be combined to describe hundreds of different speech sounds). A second type of cue is that some phoneme combinations never occur in a particular language, even in nonsense words (“tsetse,” a borrowed word from Bantu, is “illegal” in English). At the level of “real” words, a native speaker knows that if what was heard sounded like “traj,” the word actually spoken was probably “trash.” Finally, in listening to sentences, all of these lower level clues combine with knowledge of grammar and context; if what was heard was “Cake me out to the ball dame,” any native speaker of American English will know what was actually said.

A test of sentence understanding would obviously be more similar to real-world speech communication than a test using tones, nonsense syllables, or words. As one approaches real-world performance, linguistic and cognitive factors become more important (and the state of the ears becomes relatively less important). Children, nonnative speakers, and people who are intoxicated, sick, demented, or just tired perform less well on speech tests than alert, cooperative adults who are native speakers—and the differences in performance are greatest for sentences. Even elderly people without frank dementia have more difficulty remembering sentences than individual words they have just heard (Gordon-Salant and Fitzgibbons, 1997). Any speech test that is proposed for use in disability determination will be vulnerable to these nonauditory effects.

If the job requires speech communication in English, the distinction between auditory and nonauditory problems may be unimportant, but many people who speak English poorly have jobs where other languages are spoken exclusively, and for them a test of ability to understand English is irrelevant to their ability to work.

In routine clinical practice, speech understanding is tested without permitting the subject to see the speaker, yet much of everyday speech, including speech in the workplace, occurs in a face-to-face context, permitting the use of visual cues for “speech-reading.” Vision is especially important in difficult listening situations. For example, Grant and Seitz (2000) presented unfamiliar sentences (e.g., “the birch canoe slid on the smooth planks”) together with background noise as intense as the sen-

tences to 34 patients with mild to severe hearing loss. When listening without vision, the patients could identify only about half of the key words in the sentences (mean = 49 percent correct, range = 9 to 87 percent), but when they were allowed to see the speaker’s face, performance improved markedly (mean = 84 percent, range = 56 to 99 percent). In almost all cases, the addition of vision reduced the number of errors made by more than 50 percent. In another study of patients with hearing loss ranging from mild to moderately severe, speech-reading ability (estimated by the improvement in performance when subjects could see the speaker) was a strong predictor of self-reported disability—almost as strong as PTA or speech threshold in quiet, and much stronger than the ability to understand speech in noise without vision (Corthals et al., 1997). These studies probably did not include people with significant visual impairment, but it seems obvious that people with substantial impairments in both vision and hearing would have greater difficulty in face-to-face conversation than people with equivalent hearing loss and good vision.

In the workplace, training and experience must be added to the list of important nonauditory factors. Specialized vocabulary and frequently used phrases, once learned, make communication on the job easier, especially in the presence of background noise or distortion. Workers who know the job well can often predict, based on the task being done at the time, which of these stereotyped messages is most likely to be delivered. Standardized hearing tests cannot measure these skills.

Even after considering some of the factors described above, individuals vary in the degree of difficulty they report for a given degree of hearing loss. Some deny that they have a problem, while others complain of it (Demorest and Walden, 1984). Additional factors that seem to increase the likelihood of elevated complaint behavior include youth, neurosis, and low intelligence quotient (Gatehouse, 1990).

PREVALENCE AND DEMOGRAPHICS OF HEARING IMPAIRMENT

Prevalence of hearing loss in the United States is estimated from a number of different sources, which collect their data using varying procedures. The National Health Interview Survey (Pleis and Coles, 2002), which publishes the prevalence of chronic health conditions reported by adults, estimates that 17 percent of adults in the United States, or 34 million people, indicate some hearing difficulty. The prevalence of men experiencing hearing difficulty is greater than the prevalence of women experiencing hearing difficulty, with 20.8 percent of adult men having hearing trouble compared to 14.1 percent of adult women having hearing trouble. In addition, the prevalence of reported hearing loss increases

with age: 8.4 percent of the population ages 18-44, 20.6 percent of the population ages 45-64, 34.1 percent of the population ages 65-74, and 50.4 percent of the population age 75 and older report some problems with hearing. These estimates include persons with conductive and sensorineural hearing loss and are not verified directly with audiometric examination.

Hearing loss prevalence is also derived from direct audiometric assessment in representative samples of the population. For example, a population-based epidemiological study conducted in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, examined vision and hearing in the older population of a predominantly white, non-Hispanic Midwestern town. Among older adults ages 48-92 in this study, the prevalence of measured hearing loss (defined as a PTA 5124 of 25 dB or greater) was 45.9 percent. Prevalence in the subgroup ages 48-59 was 21 percent (Cruickshanks et al., 1998). This rate appears to be congruent with the rate of self-reported hearing loss. The prevalence of severe to profound hearing loss among the U.S. population has also been estimated from national data and ranges from 464,000 to 738,000, with 54 percent of this population over age 65 (Blanchfield et al., 2001).

Among children, the estimated prevalence of hearing loss is 1.26 percent based on family report (National Center for Health Statistics, 1996). Other reports suggest that 5 percent of children 18 years and under have hearing loss (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1991). Measured hearing thresholds in a sample of children ages 6-19 are available from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-III). Niskar et al. (2001) suggest that 12.5 percent have noise-induced hearing threshold shifts in one or both ears. Projecting this prevalence rate to the national population suggests that approximately 5.2 million children are estimated to have noise-induced threshold shifts in one or both ears. Among every 1,000 children in the United States, 83 have an education-ally significant hearing loss (U.S. Public Health Service, 1990). The total number of students receiving special education services for hearing loss in the United States is 43,416 (Gallaudet Research Institute, 2002). The number of children among this sample with known additional disabilities is 14,588, or 33.6 percent.

The rate of hearing aid and cochlear implant use by persons with hearing loss is relatively low, especially among adults. The total number of persons using a hearing aid in the United States is approximately 4.15 million (12.2 percent), with the majority of users age 65 and older (National Center for Health Statistics, 2002). In the Beaver Dam Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study, the prevalence of hearing aid use among adults ages 48 to 92 with hearing loss was 14.6 percent (Popelka et al., 1998). In the United States, about 13,000 adults have cochlear implants

and nearly 10,000 children have them (National Institute for Deafness and other Communication Disorders, 2004). Among children receiving special educational services for hearing loss, 6.2 percent use a cochlear implant and 62.9 percent use a hearing aid for instructional purposes (Gallaudet Research Institute, 2002).

THE SOCIAL SECURITY CONTEXT4

SSA administers benefits programs for people with long-lasting disabilities that severely affect their ability to work or, for children, to perform everyday activities like their peers. Under Title II of the Social Security Act, workers covered by Social Security may qualify for benefits called Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI, often referred to as DI). Under Title XVI, adults and children whose income and assets are low may qualify for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) disability benefits, which are means-tested. It is possible for a beneficiary to qualify for and receive both SSDI and SSI benefits, and nearly 10 percent of Social Security disability beneficiaries do so.

When children and adults apply for disability benefits and claim that a hearing loss has limited their ability to function, SSA is required to determine their eligibility for disability benefits. (See Appendix A for a glossary of terms used in reference to SSA disability programs.) To ensure that these determinations are made fairly and consistently, SSA has developed criteria for eligibility and a process for assessing each claimant against the criteria. The criteria are designed to make the determination process as objective as possible, but to leave some room for considering individual circumstances. The criteria include duration and severity of the disabling condition, employment and income (and assets for SSI), “medical listings” of conditions that are presumptively disabling, and the vocational factors of age, education, and work experience.

In the case of adults with hearing loss, SSA has medical listings criteria that partially correspond to the conventional audiological definition of “profound” hearing loss (see Chapter 3 for categorization of hearing loss). These criteria are identical for SSDI and SSI benefits. For people who do not meet the medical listings criteria, additional tests of hearing may be used to evaluate functional capacity, but there are no clear guidelines at present for evaluating hearing losses that do not meet the medical listings criteria.

SSDI is funded by the Social Security Trust Fund, the same trust fund as the well-known SSA retirement program. It is a contributory plan; that is, one must have worked under and contributed to the Social Security tax program (FICA) to be eligible for these benefits. SSDI covers only working-age adults and their dependents. At retirement age, SSDI beneficiaries transition to the retirement benefits program.

SSI is a means-tested program for old-age assistance, aid to the blind, and aid to permanently and totally disabled adults. Disabled children from families with limited income and resources are also covered under this program. The program considers both income and assets in its means-testing. SSI disability determinations are made using the same process and criteria as the SSDI program. SSI children who are 18 and under are evaluated using a process and criteria different from those applied to adults. Funding for this program is not from the Social Security Trust Fund; SSI is primarily funded through congressional appropriations. Adult eligibility for entitlement under both the SSI and SSDI programs is based on demonstrating that a disabling, medically determinable impairment is present in an individual whose labor earnings capacity has fallen below a set limit, termed substantial gainful activity (SGA). Neither SSDI nor SSI has provisions for variable benefits based on severity of impairment; the claimant either meets the disability criteria or does not.

SSI is the only program of the SSA that covers children with disability. The definition of disability for children is somewhat different from that for adults, and it has been changed more than once in recent years in response to litigation and legislation. Currently, if children do not meet the specifically listed medical criteria defining disability, they must be considered under an equivalence standard. The equivalence of their impairment to the specifically listed medical criteria must be evaluated by its medical or functional consequences; that is, it can medically equal a listed criterion or, using the functional domains cited in the SSA regulations, it can be judged functionally equivalent to the intent of the listings. The methodology used to make this decision is discussed in a later section.

Social Security Disability Determinations and Caseload for Hearing Impairment

Early in this study, the SSA provided the committee with statistical tables on claimants and beneficiaries with hearing impairments for the years 1997-2001 for determinations and 1998-2001 for numbers of beneficiaries. The SSA staff noted that the statistics from which these tables were prepared are subject to various types of error but are the best data available. Over the period 1998 through 2001, the total number of current

beneficiaries with a primary diagnosis of hearing impairment, including both SSDI (Title II) and SSI (Title XVI) beneficiaries, increased from just under 100,000 to nearly 106,000. In addition, 10,686 (in 1998) to 21,876 (in 2001) beneficiaries annually received benefits with hearing as a secondary impairment.

SSA did not provide figures for dollar costs of hearing impairment benefits. However, SSA was recently able to provide us with the number of beneficiaries in current pay status (as of May 2004) for hearing and related impairments (vertiginous syndromes, other ear disorders, and deafness), shown in Table 1-1, and with average monthly benefits for all disability beneficiaries. The average monthly benefit for DI disabled workers in 2003 was $844 and the average paid to SSI disabled beneficiaries was $433, but payment amounts specifically for hearing-impaired beneficiaries were not available. If it is assumed that these beneficiaries received the average benefit, then at this time the DI worker beneficiaries, primary and secondary, were receiving over $60 million per month and SSI beneficiaries were receiving a bit over $31 million per month in benefits. (Non-worker beneficiaries are not included in these estimates, because their average benefit was not provided.) This comes to a total of nearly $1.1 billion per year.

For the years 1997-2001, the total number of claims per year with a primary diagnosis of hearing impairment showed no major change, varying between 15,400 and 16,600. The percentage of these claims allowed (awarded benefits) increased from 39 percent in 1997 to 47 percent in 2001. The overall number of disability claims has been rising since 2001 (Social Security Administration, 2004), but we do not have the most recent figures for hearing impairment claims. Claim allowance rates are consistently highest for children under age 5 and for older working-age adults.

TABLE 1-1 SSA Beneficiaries in Current Pay Status for the Impairment Codes of Vertiginous Syndromes, Other Ear Disorders, and Deafness, May 2004

|

Beneficiary Type |

Disability Insurance: Workers |

Disability Insurance: Auxiliarya |

Supplemental Security Income |

|

Primary impairment |

57,847 |

9,748 |

56,838 |

|

Secondary impairment |

13,543 |

1,879 |

14,800 |

|

aDI nonworker beneficiaries, such as spouses and children. |

|||

In parallel with this, the proportion of allowed claimants meeting or equaling the listings is lowest for children under age 5 and for older adults, but is above 90 percent for claimants over age 18 and under age 54 across this time period. This indicates that the youngest and oldest groups are more likely to receive favorable determinations based on vocational factors for adults or on functional equivalence to the listings for children.

Procedures for Determining Disability

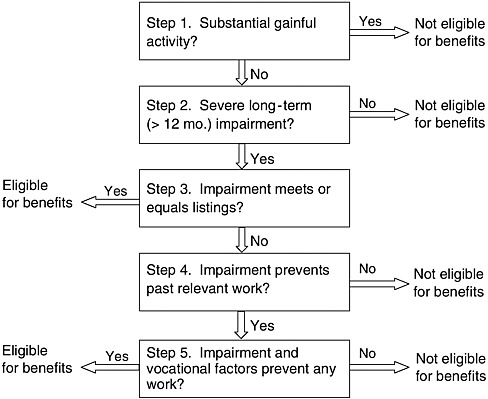

SSA reviews all claims for disability benefits using its sequential evaluation process. For adults, the process has five steps; for children, a three-step process is used.

Adults

For adults covered by SSDI and for adult SSI claimants, the disability determination process follows the steps shown in Figure 1-1. The first step of the sequential evaluation process requires that the disability examiner working on behalf of SSA determine whether the claimant is engaged in SGA. Each year the SSA formally establishes an average monthly earnings level that serves to define SGA for disability. For 2004, the monthly SGA limit is $810 for disabled claimants. If the claimant is determined not to be performing SGA, the case goes on to Step 2 of the sequential evaluation process. If the claimant is determined to be performing SGA, she or he is found ineligible for benefits at this step.

At Step 2, the claimant must document through a report or medical records provided by an acceptable medical source that a medically determinable impairment is present that significantly limits his or her physical or mental ability to do basic work activities. Furthermore, medical evidence must support a judgment that the limitations imposed by the impairment have lasted or can be expected to last for at least 12 months or are expected to lead to the claimant’s death. If these criteria are satisfied, the claim progresses to Step 3. If the criteria are not satisfied, the claimant is found ineligible for benefits at this step.

Step 3 of the sequential evaluation process uses medical criteria as a screening test to identify claimants who are obviously disabled. In this step, SSA must decide whether the claimant’s medically determinable impairment(s) meets or equals in severity the specific medical criteria listed in 20 CFR Part 404, Subpart P, Appendix 1. This decision requires concurrence of a medical or psychological consultant. If the claimant has an impairment that is determined to meet or equal the listed criteria and that level of impairment severity has been demonstrated to have lasted or is expected to last for at least 12 months or to end in death, the claimant is

FIGURE 1-1 SSA decision flow for adult disability determination.

found eligible for benefits. If not, the process continues to the consideration of vocational factors in Steps 4 and 5.

At this point in the process, the adjudicative team assesses the residual functional capacity of the claimant. Form SSA-4734-BK, called “Physical Residual Functional Capacity Assessment,” is used for physical impairments, and Form SSA 4734 is used when a mental impairment has been identified. These are assessments of what the claimant can do in spite of any physical and mental impairment over a 12-month period of time. The forms require assessment of exertional, postural, manipulative, visual, communicative, and environmental limitations. The auditory functions listed include pure-tone threshold, tested by air and bone conduction, and speech discrimination (test unspecified).

In Step 4, the decision makers must determine whether any of the claimant’s physical and mental limitations cited in the evaluations of residual functional capacity precludes the performance of “past relevant work.” If the claimant is found able to perform past relevant work in spite of cited physical and mental limitations, he or she is found ineligible for

benefits. If the claimant is found unable to perform past relevant work, the claim goes to Step 5.

In Step 5, the SSA uses a defined set of profiles and rules that consider the claimant’s age, education, and work experience or skills. A decision is made whether the claimant is capable of performing any work in the U.S. economy. A so-called vocational grid is used as a decision aid, embodying the rules for determining disability. The grid combines the vocational factors and recommends findings for various combinations. Constructed in 1979 based on information from the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (Social Security Advisory Board, 2003), the grid reflects SSA’s evaluation of the existence of work in the national economy. It was designed to be used in cases of limitations of strength and stamina, for example, to consider whether a claimant is able to perform “sedentary,” “light,” “medium,” or “heavy” work. It is not useful for other functional limitations, for which the assessment must be based on professional judgment. In practice, the claimant’s age is quite important in this determination, with older claimants, especially those over 55, not expected to learn new skills to find a job in a new line of work.

If the claimant is found to have a disability under the rules of Step 5, he or she is eligible for benefits. If he or she is found not to have a disability, benefits are denied. If a claimant disagrees with SSA’s decision, several levels of appeal are available.

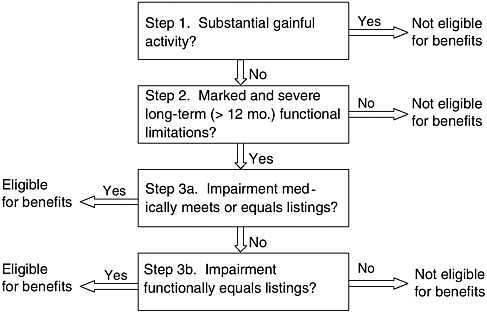

Children

For children (covered only under SSI), a slightly different set of steps is followed, as shown in Figure 1-2.

Steps 1 and 2 are the same as for adults. Step 3 for children is initially the same as for adults. If a child is determined to have an impairment that meets or medically equals the criteria cited in the listings, and that impairment is expected to last for 12 months or to end in death, the child is eligible for SSI disability benefits. Because Steps 4 and 5 for adults are not appropriate for children, an additional decision point has been added to Step 3 of the process for children. Under rules that took effect January 2, 2001, when a child is found to have a medically determinable impairment that does not meet or medically equal a listed criterion, SSA must make a determination of whether the child’s impairment(s) functionally equals the intent of the listings.

The fundamental decision to be made is whether the functional effects of the impairment(s) are “marked and severe.” This is judged mainly on the child’s ability to perform in six functional domains compared with normative data based on the ability of an unimpaired child of the same age. The regulations specify the functional domains to be considered and

FIGURE 1-2 SSA decision flow for infant and child disability determination.

give examples of age-appropriate levels of functioning for various age groups (20 CFR §416.924-926a). The regulations state that “marked” limitation “is the equivalent of the functioning we would expect to find on standardized testing with scores that are at least two, but less than three, standard deviations below the mean” (20 CFR §416.926a, (e) (ii)). “Extreme” limitation is described in a subsequent section as equivalent to at least three standard deviations below the mean. Box 1-1 shows the six functional domains.

If the child meets the functional equivalence criteria, which may be satisfied by showing marked limitations in two or more domains or extreme limitation in one domain, she or he is judged medically eligible for benefits. If not, she or he is ruled ineligible. All children who receive benefits must have their eligibility reviewed when they reach age 18, based on the adult SSI criteria.

Current Disability Criteria for Hearing

In the discussion of Step 3 of the sequential evaluation process, we mentioned the listing of impairments found in Appendix 1 of Subpart P of 20 CFR Part 404. The hearing listings are based on measures of pure-tone threshold, using air and bone conduction, and on speech discrimination testing.

|

BOX 1-1

SOURCE: 20 CFR §416.926a. |

Criteria for Adults

The requirements for testing and for documenting hearing loss of adults are as follows (Social Security Administration, 2003a, p. 24):

Loss of hearing can be quantitatively determined by an audiometer which meets the standards of the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) for air and bone conducted stimuli (i.e., ANSI S3.6-1969 and ANSI S3.13-1972, or subsequent comparable revisions) and performing all hearing measurements in an environment which meets the ANSI standard for maximal permissible background sound (ANSI S3.1-1977).

Speech discrimination should be determined using a standardized measure of speech discrimination ability in quiet at a test presentation level sufficient to ascertain maximum discrimination ability. The speech discrimination measure (test) used, and the level at which testing was done must be reported.

Hearing tests should be preceded by an otolaryngologic examination and should be performed by or under the supervision of an otolaryngologist or audiologist qualified to perform such tests.

In order to establish an independent medical judgment as to the level of impairment in a claimant alleging deafness, the following examinations should be reported: Otolaryngologic examination, pure tone air and bone audiometry, speech reception threshold (SRT), and speech discrimination testing. A copy of reports of medical examination and audiologic evaluations must be submitted.

Cases of alleged “deaf mutism” should be documented by a hearing evaluation. Records obtained from a speech and hearing rehabilitation center or a special school for the deaf may be acceptable, but if these

reports are not available, or are found to be inadequate, a current hearing evaluation should be submitted as outlined in the preceding paragraph.

The criteria for hearing loss severe enough to be taken as prima facie evidence of disability in adults are (p. 26):

-

Average hearing threshold sensitivity for air conduction of 90 decibels or greater, and for bone conduction to corresponding maximal levels, in the better ear, determined by the simple average of hearing threshold levels at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz.; or

-

Speech discrimination scores of 40 percent or less in the better ear.

Criteria for Children

The listings include special provisions for the evaluation of children (Social Security Administration, 2003a, p. 111):

The criteria for hearing impairments in children take into account that a lesser impairment in hearing which occurs at an early age may result in a severe speech and language disorder.

Improvement by a hearing aid, as predicted by the testing procedure, must be demonstrated to be feasible in that child, since younger children may be unable to use a hearing aid effectively.

The type of audiometric testing performed must be described and a copy of the results must be included. The pure tone air conduction hearing levels in 102.08 are based on American National Standard Institute Specifications for Audiometers, S3.6-1969 (ANSI-1969). The report should indicate the specifications used to calibrate the audiometer.

The finding of a severe impairment will be based on the average hearing levels at 500, 1000, 2000, and 3000 Hertz (Hz) in the better ear, and on speech discrimination, as specified in 102.08.

The listing criteria for children are as follows (pp. 111-112): 102. 08 Hearing Impairments

-

For children below 5 years of age at time of adjudication, inability to hear air conduction thresholds at an average of 40 decibels (db) hearing level or greater in the better ear; or

-

For children 5 years of age and above at time of adjudication:

-

Inability to hear air conduction thresholds at an average of 70 decibels (db) or greater in the better ear; or

-

Speech discrimination scores at 40 percent or less in the better ear; or

-

Inability to hear air conduction thresholds at an average of 40 decibels

-

(db) or greater in the better ear, and a speech and language disorder which significantly affects the clarity and content of the speech and is attributable to the hearing impairment.

As noted above, a child’s impairments are considered to be functionally equivalent to the intent of the listings if he or she has “marked” limitations in two broad domains of function (see Box 1-1) or an “extreme” limitation in one domain.

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH5

Models of Disability

The conceptual model underlying disability determination has been undergoing changes over the past several years, especially since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990. One newer conceptualization follows a social model of disability, which postulates that factors both within the individual and in his or her physical and social/cultural environment combine to influence performance and participation in everyday situations. An even newer formulation, the “new paradigm” discussed by Pledger (2003), recognizes a “disability culture” and approaches some issues as matters of civil rights for a minority group. This approach stresses respect for people with disabilities as being capable of self-determination and independent decision making. It also advocates for people with disabilities to be in charge of their own assistance and accommodations, rather than to have others determining what they need.

These newer models replace the earlier stress on disability or handicap and the negative aspects of an individual’s situation, emphasizing instead the person’s remaining capabilities and how they can best be supported to permit full economic and social participation. They also replace earlier implications that disability was the simple and inevitable result of an impairment. The ADA, based on the social model, represents a commitment in the United States to help individuals with disabilities to participate as fully as possible in the society and the economy.

The social model also underlies the approach now taken by the World Health Organization toward disability and handicap. Whereas The International Classification of Impairment, Disability, and Handicap (ICIDH) (World Health Organization, 1980) established definitions for these

terms, the newer International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (World Health Organization, 2001) is an attempt to fully account for the interactions between the individual and the physical and social environment in determining the participation of an individual with a disability. Further discussion of disability models is presented in Chapter 6, where social and environmental aspects of disability are considered.

Predicting Disability from Clinical Tests

The committee carefully considered the social model as it applies to those with hearing loss, recognizing that the measured severity of hearing loss does not inevitably predict a person’s disability or handicap. However, this model does pose a dilemma for using the measurement of hearing loss as a surrogate for determining level of disability. In reviewing data on audiological testing and functional status, the working hypothesis was deceptively simple: increasingly severe hearing loss, by some measure, is associated with increasing inability to carry out activities associated with employment or, in the case of children, age-appropriate activities. The data bearing on this issue present a more complicated picture, because the same level of hearing loss can result in a wide spectrum of disability level, depending on such diverse factors as duration and age of onset of hearing loss, availability and quality of habilitation or rehabilitation services, education, age, gender, psychological adjustment, presence of other comorbid conditions, and social and environmental support. Thus, there is a great variability in functional status for any given level of hearing loss.

The committee evaluated the fifth edition of the American Medical Association’s Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment (American Medical Association, 2001). These guides, used in many workers’ compensation procedures for disability determination, represent a more traditional quantitative approach to evaluating impairment and disability. The chapter on philosophy, purpose, and appropriate use of the Guides in the fifth edition explains: “The Guides continues to define impairment as ‘a loss, loss of use, or derangement of any body part, organ system, or organ function.’” (p. 2). The chapter also states (pp. 4-5):

The whole person impairment percentages listed in the Guides estimate the impact of the impairment on the individual’s overall ability to perform activities of daily living, excluding work…. The medical judgment used to determine the original impairment percentages could not account for the diversity or complexity of work but could account for daily activities of most people. Work is not included in the clinical judgment for impairment percentages for several reasons: (1) work in-

volves many simple and complex activities; (2) work is highly individualized, making generalizations inaccurate; (3) impairment percentages are unchanged for stable conditions, but work and occupations change; and (4) impairments interact with such other factors as the worker’s age, education, and prior work experience to determine the extent of work disability.

The section on disability in this chapter of the Guides discusses the evolving definitions of the term, and then states (p. 8):

The Guides continues to define disability as an alteration of an individual’s capacity to meet personal, social, or occupational demands or statutory or regulatory requirements because of an impairment. An individual can have a disability in performing a specific work activity but not have a disability in any other social role.

It also states (p. 8):

The impairment evaluation, however, is only one aspect of disability determination. A disability determination also includes information about the individual’s skills, education, job history, adaptability, age, and environmental requirements and modifications. Assessing these factors can provide a more realistic picture of the effects of the impairment on the ability to perform complex work and social activities. If adaptations can be made to the environment, the individual may not be disabled from performing that activity.

On the whole, the AMA Guides are in agreement with the current belief that impairment is only one of several factors determining an individual’s ability to perform in daily life and the workplace and, consequently, that many factors beyond medical impairment criteria should be considered in determining whether any individual has a disability in a given situation. Table 1-2 illustrates the definitions of impairment and disability used in several systems.

In contrast to this approach, SSA currently uses “disability” or “disabled” as a term that applies to those who are deemed eligible for disability benefits as a result of the formal determination process. The agency uses the terms to describe the relationship of the person to the criteria for its programs, not necessarily as a description of his or her personal functional status.

The SSA disability determination process follows a path starting with a medical model, embodied in the listings of impairments, through Step 3 of the decision process. The listed medical conditions are assumed to produce impairments so severe that individuals are disabled by the mere presence of the condition, as determined by clinical diagnostic markers. For persons whose conditions meet or equal the listings and who are not engaged in SGA, SSA does not require that functional capacity be evalu-

TABLE 1-2 Definitions of Impairment and Disability

|

Organization |

Impairment |

|

American Medical Association Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment (5th ed., 2001) |

A loss, loss of use, or derangement of any body part, organ system, or organ function. |

|

World Health Organization (1999) |

Problems in body function or structure as a significant deviation or loss. Impairments of structure can involve an anomaly, defect, loss, or other significant deviation in body structures. |

|

Social Security Administration (1995) |

An anatomical, physiological, or psychological abnormality that can be shown by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques. |

|

State workers’ compensation law (typical) |

Permanent impairment “is any anatomic or functional loss after maximal medical improvement has been achieved and which abnormality or loss, medically, is considered stable or nonprogressive at the time of evaluation. Permanent impairment is a basic consideration in the evaluation of permanent disability and is a contributing factor to, but not necessarily an indication of, the entire extent of permanent disability (Idaho Code section 72-422). |

|

SOURCE: American Medical Association (2001, p. 3). |

|

|

Disability |

Physicians’ Role |

Comments |

|

An alteration of an individual’s capacity to meet personal, social, or occupational demands because of an impairment. |

Determine impairment, provide medical information to assist in disability determination. |

An impaired individual may or may not have a disability. |

|

Activity limitation (formerly disability) is a difficulty in the performance, accomplishment, or completion an activity at the level of the person. Difficulty encompasses all of the ways in which the doing of the activity may be affected. |

Not specifically defined; assumed to be one of the decision makers in determining disability through impairment assessment. |

Emphasis is on the importance of functional abilities and defining contextrelated activity limitations. |

|

The inability to engage in any substantial, gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment(s), which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months. |

Determine impairment, may assist with the disability determination as a consultative examiner. |

Physicians and nonphysicians need to work together to define situational disabilities. |

|

“Temporary disability” means a decrease in wage-earning capacity due to injury or occupational disease during a period of recovery (Idaho Code section 72-102[10]). “Permanent disability” results when the actual or presumed ability to engage in gainful activity is reduced or absent because of permanent impairment and no fundamental or marked change in the future can be reasonably expected (Idaho Code Section 72-423). |

“Evaluation (rating) of permanent impairment” is a medical appraisal of the nature and extent of the injury or disease as it affects an injured employee’s personal efficiency in the activities of daily living, such as self-care, communication, normal living postures, ambulation, elevation, traveling, and nonspecialized activities of bodily members (Idaho Code section 72-424). |

Purpose is to provide sure and certain relief to those who become injured by accident or suffer effects of disease from exposure to hazards arising out of and in the course of employment. |

ated to determine eligibility for benefits. This “screening in” at Step 3 is important to the SSA as a way to minimize the number of claimants for whom Step 4 and 5 consideration of vocational factors, an expensive and time-consuming process, must be performed. The criteria are purposely set high, since the additional steps will give all claimants not meeting the listing criteria an opportunity to be found eligible for benefits.

For those whose conditions do not meet or equal the medical listings, SSA switches in Steps 4 and 5 to a more complex model, performing an evaluation of functional capacity in relation to the work environment (based on a model of physical work demands). The process evaluates the claimant’s ability first to perform in recent relevant employment (Step 4) and then to perform any work in the U.S. economy (Step 5). The vocational grids mentioned earlier are used as decision aids when the impairment is in the ability to perform physical labor, but for other work, the guidance is sparse at best. The decision maker considers the claimant’s age, education, and work experience as well as, by inference, transferable skills. At this time, SSA prescribes no formal tests or evaluation protocols (beyond the Residual Functional Capacity form completed by a physician) to determine what the claimant actually can do; no formal method for determining what disability might result from an individual’s impairments in the living and work environments; nor any assessment of the mitigating effects of environmental accommodations or assistive technology. Also there also is normally no face-to-face meeting between the claimant and the decision maker in the initial determination process, although this may change if some current pilot programs are successful. Vocational experts may be brought in to aid the decision making. In practice, the claimant’s age is important in this evaluation; most older claimants, especially those over age 55, are not expected to learn new skills to find a job in a new line of work.

A recent report by the Social Security Advisory Board (2003) discussed in depth several difficulties with the SSA’s current approach. It noted that (Social Security Advisory Board, 2003, p. 7):

The core definition of disability for the Social Security program adopted fifty years ago was inability to do substantial work by reason of a physical or mental impairment. That core definition itself remains unchanged, but the context in which it operates has changed a great deal, and its validity, both as an administratively feasible definition and as an appropriate standard of benefit eligibility, is increasingly subject to challenge.

The report discussed several issues that are problematic, including the following (p. 17):

The concept of disability has both medical and functional components. The world of work has a wide variety of tasks that require a range of

physical and intellectual functional capacities. . . Therefore a given medical condition may or may not be “disabling” depending on the specific functional capacities and how they interact with the educational and vocational profile of the affected individual. A medical condition that precludes highly exertional physical activity may be “totally” disabling for an older individual with little education and an unskilled work history and not disabling for another individual who is highly skilled and educated.

In a theoretical sense, accurately determining disability for Social Security disability benefits would require that each individual be evaluated to determine how their medical condition limits their functional capacity and then how these limitations interact with each individual’s age, work history, and education. The end result would be a decision whether the medical impact on the individual’s functional capacities makes work feasible.

The report acknowledged that the volume of claims has always made such individual evaluations of all claimants impracticable, but noted also (p. 7):

[T]he proportion of initial allowances based strictly on medical factors has declined from around 93 percent in the early years of the program to 82 percent in 1983 and to a 2000 level of 58 percent. By the end of the appeals process, the proportion of allowances made on strictly medical factors is around 40 percent, and because of coding deficiencies, possibly even lower.6

As noted above, individualized assessments of vocational disability require knowledge of the specific demands of jobs. The committee reviewed some of the job taxonomies now available and considered the reviews conducted by a previous NRC committee on visual impairments (National Research Council, 2002), but we could not identify a database of job demands that would be usable for SSA disability determination at this time. The Disability Research Institute, a research consortium under contract to the SSA, has reached a similar conclusion. A recent technical report (Heinemann et al., 2002) from their project on job demands reviewed several systems and taxonomies that could serve as information sources for SSA in determining the job demands of various occupations. It stated (Heinemann et al., 2002, p. 42):

In summary, there are several reasons for conducting a separate study for generating job demand variables for SSA’s use in disability determinations. Some of the important reasons are: (a) Existing job analysis sys-

|

6 |

For hearing impairment, the percentage of awardees meeting the listings is still in the 90+ percent range, except for children and working age adults over age 55. |

tems do not sufficiently address the needs of SSA in assessing the RFC of claimants for the purpose of determining disability, (b) with the exception of O*NET, the available job analysis inventories (and their derived job demand variables) may not adequately reflect the fast changing world of work, especially the dot-com industry; while O*NET is a new system, its serious deficiencies in meeting the needs of SSA are well known . . . and (c) recent advances in measurement technology . . . allow for a more precise assessment and simultaneous calibration of jobs and job demand variables on a common metric.

These issues are among the ones that the committee sought to address in its approach to the determination of disability for people with hearing loss.

The Study Process

The committee performed an extensive literature review of topics relevant to the study tasks, with individual committee members reviewing the literature in their fields of special expertise. Two papers were commissioned, one on assistive listening devices and one on the literature relating hearing test performance to job performance. Data were obtained from government and other sources when appropriate.

The committee debated the criteria it should impose for accepting evidence for consideration in its work. First, it was agreed that any evidence used should be available in the open published (including on-line) literature, so that readers could examine it themselves if they wished to. We preferred to use evidence published in peer-reviewed journals but allowed other evidence as well, if we were able to determine that the work had been rigorously performed. These sources included book chapters, medical texts, papers presented at scientific and professional conferences, technical reports, and government publications. (For demographic and epidemiological data, the best sources were usually government reports.) Other evidence, such as that from unrefereed journals or advocacy groups, was evaluated very carefully before being accepted with caution.

The committee held a public forum in January 2003 to allow members of the public and representatives of service and advocacy groups to provide information. About 80 organizations working with deaf and hard-of-hearing people were sent invitations to nominate forum speakers, and seven speakers subsequently participated. Each speaker was asked to respond to a set of prepared questions, to encourage them to focus their remarks on issues relevant to the committee’s tasks. All of the organizations were invited to have their representatives attend as guests as well. There was time at the forum for open discussion and questions from

guests. Appendix C includes lists of the organizations invited to nominate speakers, the speakers, and the registered guests.

Guide to the Report

The remainder of this report is divided into six chapters. In Chapter 2 we review the basic mechanisms of hearing and the functioning of the human auditory system and describe the types of hearing loss and their causes. In Chapter 3 we review the testing of adult hearing and of the auditory system, beginning with a description of a standard otological exam and then turning to audiological testing. The chapter reviews current tests and test theory and describes and evaluates the tests now mandated by the SSA for hearing disability determination and other tests that were considered for possible use as replacements or augmentations of those tests. We also discuss test conditions and protocols. In Chapter 4, we present our conclusions on the testing of adults and our recommendations for tests and testing procedures. Chapter 5 is devoted to a discussion of technological aids that can mitigate the effects of hearing loss: hearing aids, prostheses such as cochlear implants, and assistive listening devices. We review the state of the art for each type of device, discussing what is known about how well each can improve the functioning of people with hearing loss. In Chapter 6, we discuss what is known of the effects of hearing loss on everyday life, work performance, and psychosocial adjustment. We evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of some instruments used to measure these effects and review some psychometric issues involved in their design and interpretation. Finally, Chapter 7 addresses hearing loss in children. The chapter reviews the effects of hearing loss on children’s speech, language, and educational development and the special requirements and challenges of the development of hearing tests for children. We review and evaluate current tests and present conclusions and recommendations for testing children’s hearing, speech, and language competence for SSA disability determination.

Four appendixes provide additional information. Appendix A consists of two glossaries of SSA and technical terms. Appendix B describes the standards of the American National Standards Institute pertaining to bioacoustics that are referenced in the report. Appendix C lists the organizations and speakers who were invited to the committee’s public forum. Appendix D consists of biographical sketches of committee members and staff.