2

New Orleans Before and After Katrina

Two speakers at the workshop provided historical perspectives on the experiences of New Orleans with hurricanes. Craig Colten, the Carl O. Sauer Professor of Geography at Louisiana State University, compared the experiences of New Orleans during Hurricane Betsy in 1965 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to track the evolution of resilience in the city over the past half century. Allison Plyer, co-deputy director of the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, provided a statistical analysis of the New Orleans Metropolitan Area since Katrina to highlight both the accomplishments and the challenges of the post-Katrina period.

FORGETTING THE UNFORGETTABLE: CRAIG COLTEN

On September 9, 1965, Hurricane Betsy struck New Orleans with winds over 100 miles per hour. At the time, except for the shore of Lake Pontchartrain, only modest barriers protected shorelines from flooding, and the city had more residents than it does today. The storm, which inundated less than half the urban area of New Orleans, caused considerable but not overwhelming damage to residences, and the state of Louisiana suffered just over 80 deaths (Colten and Sumpter, 2008).

Almost exactly 40 years later, the city had a much more formidable hurricane protection levee system, and the population of the city had fallen from 627,000 residents in 1965 to circa 437,000 residents just before Katrina (Kates et al., 2006; Williamson, 2010). Yet a staggering number of homes were seriously flooded or destroyed, and the storm caused more than 1,500 deaths throughout Louisiana (Kates et al., 2006).

After Hurricane Betsy, Louisiana Governor John McKeithen pledged that “nothing like this will happen again” and asserted that his administration would “establish procedures that will someday in the near future make a repeat of this disaster impossible.” Forty years later a storm of lesser magnitude caused far worse damage and fatalities. “Had the lessons of Betsy been retained?” asked Colten during his presentation. “Had they been woven into hurricane preparations and used to make the city more resilient?” The answer has to be no. Resilience eroded in the city of New Orleans between the two events, Colten said. The city did not retain the lessons of past hurricanes, and it did not plan or prepare adequately for future events. This erosion of resilience has implications for any other city that faces repeated disruptive events.

Resilience Defined

Colten defined resilience as the ability of a community to rebound after an extreme or stressful event to either the same condition or to a functional state. This definition can apply to either ecological or human communities, he observed. But human communities have the ability to learn, adapt, and adjust to subsequent disruptive events, so long as they retain lessons learned in previous events and use those lessons to adapt to future events.

Given this definition, the term resilience implies a community that anticipates problems, reduces vulnerabilities, responds effectively to an emergency, and recovers rapidly to a safer and fairer functional state. To achieve resilience, communities need to make deliberate efforts to infuse preparations with historical perspectives and to convey lessons to each generation of leaders, Colten said. They need to preserve, nurture, integrate, and perpetuate social memories of past events and use these memories as growth points for the renewal and reorganization of socioecological systems (Adger, 2000).

Changes Between 1965 and 2005

One area where there was significant improvement between the two hurricanes was in storm forecasting. The forecasting tools in 1965 included early radar systems, hurricane hunter flights, and networks of ship reports. Two days before the landfall of Betsy, the city of New Orleans and federal officials had already launched full preparation for the hurricane. A day before landfall the warning area extended from Texas to Florida.

In 2005 the National Hurricane Center produced a nearly perfect track for the hurricane 72 hours before landfall (e.g., http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/special-reports/katrina.html; accessed May 30, 2011). This emphatic warning provided impetus for the evacuation of able-bodied people and the provisioning of shelters, although many people with special needs still did not have enough time to evacuate from the city.

Colten identified four key elements that have been involved in the loss of resilience between the two hurricanes: (1) flood-proof architecture, (2) protective structures and land use, (3) local evacuation and multiple shelters, and (4) the coordination of the organizational response. Colten offered a historical context to understand these factors before Hurricane Betsy and between Betsy and Katrina.

Architecture

From the colonial era into the 1920s, Colten noted that many New Orleans homes were elevated above the floodplain. This was usually done to make them cooler in the summertime, but it also provided protection against floods. Early construction also often relied on waterproof materials such as cypress and tile, which provided some degree of resilience even when structures were not elevated.

After World War II, houses built on concrete slabs raised just a few inches above ground level largely replaced raised houses in the city limits. The city planning office noted that this slab on-grade housing was a mistake after the hurricane of 1947, but no steps were taken to restore safe construction. These houses became the dominant type of construction and were allowed by building codes (Colten and Sumpter, 2008).

Land Use

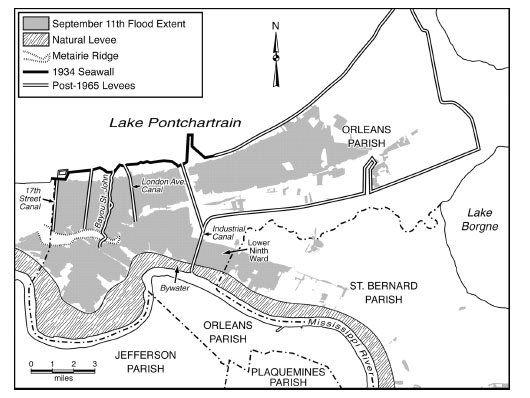

After New Orleans was founded in 1718, early settlement clustered on the narrow high ground of natural levees near the river, which provided the only solid footing and were the last areas to flood and the first to drain after flooding (Figure 2-1). As the city grew during the 19th century, it spread along the high ground, avoiding more flood-prone areas (Kates et al., 2006).

In the 20th century, housing extended into more susceptible areas as New Orleans became one of the largest cities in the United States. After a devastating hurricane in 1915 drove storm surge beyond the lakefront and into the sprawling city, the city turned to structural protection. It built a 9.5-foot seawall on the lakefront, which was completed in 1934, to keep water out of the city’s “back door.” With that barrier in place, the city expanded toward the lakefront during the economic boom of the 1920s, facilitated by public works programs that drained low-lying areas and provided water and sewer lines. By the beginning of the Great Depression, the neighborhoods of Lakeview and Gentilly were developed, and the inhabitants believed them to be safe despite their low elevations (Kates et al., 2006; see maps in Appendix D for locations of New Orleans neighborhoods).

A 1947 hurricane rekindled concern, Colten indicated, but the lakefront levees provided good protection, and developers felt it was safe to extend urban sprawl. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the Jefferson Parish lakefront levee along with other levees to protect urban areas and waterways.

FIGURE 2-1 Development occurred in areas protected by an expanding levee network between 1900 and 2005. For additional maps, see Appendix D. SOURCE: Kates et al., 2006.

Following Hurricane Betsy, the city and state appealed for enhanced structural protection to what was then a modest system. The Corps of Engineers provided a plan to Congress in July 1965 for new levees, and the plan was approved. Progress fell chronically behind schedule and the plan had not been finished in 2005, though it had originally been scheduled for completion in 1978 (USGAO, 2005; Colten and Sumpter, 2008).

Many of the new levees protected uninhabited areas, which meant that their cost could be justified only if these areas were developed. With new levees in place, urban growth largely ignored prior floods. The levees excluded the entire city from the 100-year floodplain,1 though 67 percent of the city’s homeowners had flood insurance to guard against freshwater floods (Colten, 2005; Meitrodt and Mowbray, 2006).

____________

1 A 100-year floodplain is the area that will be inundated by a flood having a 1 percent chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year. See http://www.fema.gov/plan/prevent/floodplain/nfipkeywords/flood_zones.shtm (accessed May 30, 2011).

As levees were extended following Betsy, many new subdivisions were platted in areas that were flooded in 1965. For example, 22,000 new homes were built in New Orleans East between the 1960 and 1980 censuses, representing a massive expansion of housing in areas below sea level. Jefferson Parish underwent dramatic growth during this period, with the population more than doubling. Metropolitan New Orleans added 150,000 housing units between 1965 and 1985, most of them in areas behind new but uncompleted levees (Colten and Sumpter, 2008).

Another consequence of the widespread construction of levees was subsidence of the land. When the areas behind levees were drained, the land compacted and lowered, increasing the susceptibility of housing to extreme damage if the levees failed or were overtopped.

Evacuation

During the 1965 hurricane, planning emphasized local evacuations. More than 180 shelters were available and easily accessible, so people could evacuate within minutes. Many sturdy two-story neighborhood schools were designated as shelters, providing safety, cooking facilities, and toilets. Other shelters included military bases that provided for basic needs. The state plan had enough food to provide for more than 400,000 people for 2 weeks before the storm, and cots were set up before the storm arrived (Colten and Sumpter, 2008).

On the eve of Hurricane Betsy, warnings were sent out to people living in lower coastal parishes, and city residents were urged by radio, television, and newspapers to relocate to shelters. Evacuation routes marked in previous years showed the way, and more than 300,000 people evacuated low-lying coastal areas in Louisiana (Goudeau and Conner, 1967). Many walked or took public transit, so they were not dependent on private cars.

After Betsy, development outpaced available levels of protection. With the new levees, deep submersion of the city was possible, so it was no longer possible to evacuate locally. People would need to evacuate long distances, which meant that evacuations would rely largely on private automobiles. But many people had no access to private transportation. Also, many public facilities—such as hospitals, jails, and nursing homes—opted not to evacuate given the expense of doing so.

Although at least 800,000 people left the urban area in 2005 (http://www.dhs.gov/xfoia/archives/gc_1157649340100.shtm; accessed May 30, 2011), some 100,000 remained behind (Heitman, 2010), and there were inadequate provisions for those who did not evacuate. Some people were stranded in their homes. Others fled to neighborhood schools and broke into the buildings. Others went to the convention center after the storm, seeking rescue or supplies. Approximately 10,000 people congregated at the Superdome (Filosa, 2005), and people were told to bring 3 days’ worth of their own food. Then the roof of the Superdome failed during the storm.

Response

The primary planning for the response to Hurricane Betsy was done by the Department of Civil Defense, which maintained lists of shelters and coordinated response planning. The military also played an important role, with the Coast Guard performing rescues and the National Guard providing security, and local governments providing an array of police, fire, and other services. Though there was some criticism after Betsy about the need for greater coordination, there was a remarkable lack of bickering across levels of government, said Colten.

During Katrina, the National Weather Service did an admirable job of forecasting the storm, and the city declared a mandatory evacuation with reasonable lead times. But the failure of the levees disrupted response procedures and interfered with communications. While the Coast Guard and the fire department were among the few organizations that received praise, the storm became a major social calamity, Colten indicated. The scale of the event exceeded the ability of organizations to respond at an appropriate scale. This failure at all levels led to finger pointing rather than a sense of shared responsibility, as after Betsy.

Changes Since Katrina

In general, said Colten, the lessons that should have been learned from Betsy and other hurricanes were not heeded before Katrina, and many of these lessons still are not being heeded. Although the levees are under repair and new surge barriers are in place, the city’s footprint has not been fundamentally reduced, even though the corps no longer considers the levees around New Orleans to provide protection against a 100-year flood event. Today, many houses in New Orleans are below sea level, and even some of the houses built after Katrina are ill suited for high water, said Colten.

After a protracted public process, New Orleans adopted a plan that opens the entire city to redevelopment while targeting certain areas for rebuilding, renewal, and redevelopment. Building can occur in most of the areas that were flooded and remain susceptible to future floods.

Great improvements have occurred in preparing for the evacuation of the infirm, as demonstrated by the much more successful evacuation carried out before Hurricane Gustav in 2008, and plans have been made for the establishment of more local shelters. Nonetheless, long-distance evacuation remains the major response plan.

A congressional select committee concluded that many failures in the emergency response during Katrina were attributable to inadequate cooperation and communication among government bodies responsible for preparation and response. Despite the emergence of spontaneous groups such as Common Ground to fill this void, merging their efforts with those of existing agencies and nongovernmental organizations remains problematic, Colten indicated.

Resilience as a concept is gaining widespread application. But after a calamity, immediate and deliberate steps need to be taken to identify and archive effective resilience techniques, Colten said. Social memories need to be perpetuated at all levels and all stages to enhance emergency response, recovery, and long-term reconstruction. Today, memories of Katrina remain strong, which has motivated change. Will these memories still be motivating similar behaviors when the next major hurricane strikes New Orleans?

THE NEW ORLEANS INDEX AT FIVE: ALLISON PLYER

The New Orleans Metropolitan Area has sustained three major shocks in the last five years: (1) Hurricane Katrina, (2) the economic recession that started in 2008, and (3) the oil spill caused by the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in 2010. Yet New Orleans is rebounding from all of these events, said Allison Plyer, co-deputy director of the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. It has become more resilient and is better positioned to not only adapt but transform itself in the future. Plyer added that key economic, social, and environmental trends in the New Orleans Metropolitan Area remain troubling and are testing the region’s path to prosperity.

The Greater New Orleans Community Data Center publishes the New Orleans Index with the Brookings Institution, which began publishing the index after Hurricane Katrina. For the fifth anniversary edition of the index, the Community Data Center and the Brookings Institution examined trends in the New Orleans Metropolitan Area across the past 30 years to look more deeply at issues of resilience. The resulting analysis, along with seven essays on aspects of resilience and recovery by local scholars, are being included in a book published by the Brookings Institution Press (see also Liu and Plyer, 2010)2.

Measures of Prosperity

The New Orleans Index looks at four dimensions of prosperity: (1) economic growth, (2) inclusive growth, (3) sustainable growth, and (4) quality of life. The metropolitan area includes the seven parishes of Orleans, Jefferson, St. Bernard, St. Charles, Plaquemines, St. John, and St. Tammany, though in some cases the analysis includes the three additional parishes of St. James, Tangipahoa, and Washington. The index also compares the New Orleans region to 57 “weak city”

____________

2 Allison Plyer’s remarks are sourced from a report of the Brookings Institution and the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center called “The New Orleans Index at Five: From Recovery to Transformation,” released in August 2010 [http://www.brookings.edu/reports/2007/08neworleansindex.aspx]; the Power Point presented by Ms. Plyer derives from that report and can be found here: https://gnocdc.s3.amazonaws.com/NOIat5/NOLArecoveryBriefing.ppt. Both links accessed May 30, 2011.

metropolitan regions—older industrial cities that, like New Orleans, have experienced decades of relative economic decline.

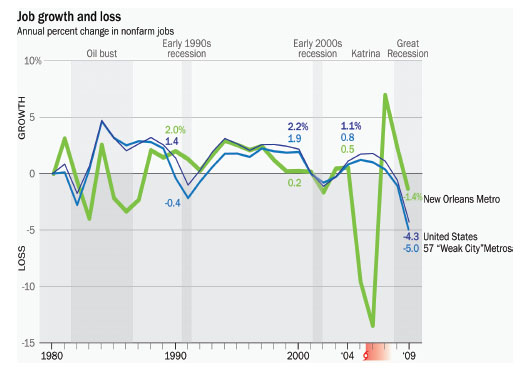

Employment data for New Orleans show a great deal of variation in the last 5 years (Figure 2-2). It lost jobs immediately after Katrina, gained jobs during the initial stages of recovery, and then lost jobs again during the recession. However, New Orleans shed fewer jobs when the recession hit, losing only 1.4 percent of all jobs between 2008 and 2009 compared with 4.3 percent nationally. Post-Katrina rebuilding and the relative strength of the oil and gas industry helped the area weather the recession better than the norm (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

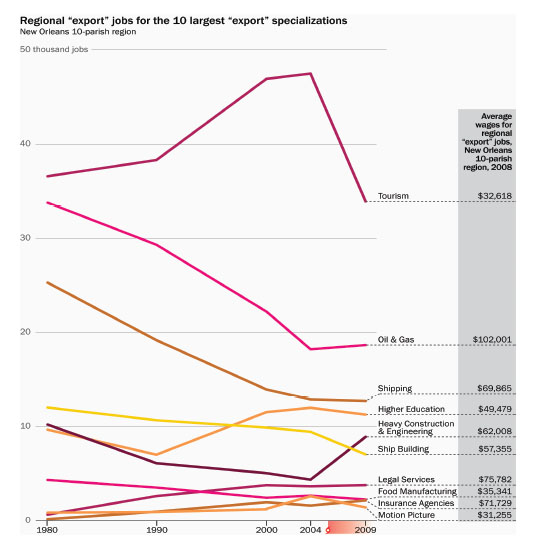

The index looks specifically at “regional export industries” that serve customers outside the region. As a broad rule of thumb, every export industry job supports about two local serving jobs. For example, one job in the oil and gas industry might support the equivalent of two dry-cleaning jobs, with export industry jobs typically paying higher wages than local serving jobs, Plyer said.

The economy of the New Orleans Metropolitan Area has been diversifying (Figure 2-3). Among regional export industries, jobs in the oil and gas industry, shipping, and ship building have dropped since 1980, as have jobs in tourism

FIGURE 2-2 Job growth and loss in New Orleans (green line) rebounded after Katrina and did not decline as much in the recent recession as the national average. SOURCE: Liu and Plyer, 2010.

FIGURE 2-3 Regional export jobs for the 10 largest export specializations have declined in traditional industries but are expanding in knowledge-based industries. SOURCE: Liu and Plyer, 2010.

since Katrina. In contrast, jobs in knowledge-based industries, such as higher education, legal services serving clients outside the region, and insurance, have increased in number. In 2009, for example, jobs in higher education became the fourth largest economic driver in the metropolitan area, exceeding shipbuilding, heavy construction, and engineering (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

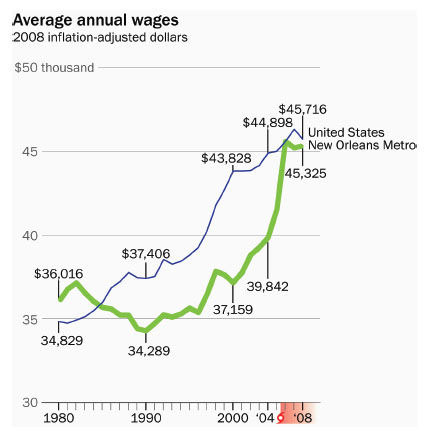

Wages in the New Orleans Metropolitan Area have grown by nearly 14 percent in the last 5 years—to about $45,000 in 2008 inflation-adjusted dollars—approaching the national average for the first time since the mid-1980s

FIGURE 2-4 Wages in New Orleans surged 14 percent after Katrina but have stagnated since 2006. SOURCE: Liu and Plyer, 2010.

(Figure 2-4). This increase in wages started before Katrina as knowledge-based industries grew, and accelerated after the storm. The median household income also grew by 4 percent from 1999 to 2008 while national median household incomes declined. These changes are due to some extent to the loss of lower-paying jobs among people who could not afford to return to the New Orleans area after the storm. However, tracking where people have moved and what has happened to them after Katrina has been difficult, so the effects of demographic changes on average incomes are very difficult to determine.

The rate at which New Orleanians are creating new businesses is higher than the national average, after lagging behind the national average before Katrina. The number of arts and culture organizations in the city also grew from 2004 to 2007, from 81 to 86, despite the city’s smaller population after Katrina (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

A greater share of students attend schools that meet state standards of quality—59 percent compared with 30 percent in 2004—which is also a trend

that accelerated after Katrina. Furthermore, these gains have occurred across all of the parishes (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

Resilience Factors

Plyer analyzed five factors that help determine resilience: (1) a strong and diverse regional economy, (2) large shares of skilled and educated workers, (3) wealth that can be deployed in strategic ways to adapt when a shock hits, (4) strong social capital, and (5) community competence.

Of these five, New Orleans has exhibited particular strength in the last three since Katrina, she said. For example, it has experienced a significant increase in community participation. More New Orleanians are involved in shaping public policies. New Orleanians are “more likely than residents of other cities to attend public meetings… . Individuals and groups have become more strategic and sophisticated … and there is greater cooperation between organizations, including the emergence of new umbrella groups” (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

The recovery has seen the rise of sophisticated resident and community groups. These groups are pursuing holistic strategies to revive entire neighborhoods and are engaging in effective policy advocacy to pursue economically integrated housing and neighborhoods, Plyer indicated. The federal government has “taken steps to overhaul the troubled housing authority,” and low-income households are being provided with quality, permanent, and affordable housing (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

After years of meetings, New Orleanians have an approved master plan designed to guide the city toward a modern and secure future that also recognizes the culture and history of the city (see http://www.nolamasterplan.org/; accessed May 30, 2011). The plan provides for predictable development and formalizes the community participation process. “Citizens and civic leaders have also advocated for and won critical governance reforms, such as the consolidation of the levee boards, the merger of the city’s seven property assessors into one office, [and] the creation of the Office

of the Inspector General….” (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

In the area of education, the majority of the schools in the New Orleans school district were converted to charter schools after Katrina. Many school facilities have been upgraded, and new teachers have been recruited. A higher percentage of eighth and fourth graders are proficient in mathematics and English today than before the storm (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

In health care, the metropolitan area now “provides access to primary care and outpatient mental health services at 93 sites across four parishes… . Emergency room visits have declined as patients have increased their visits for preventive care” through this new system of health care delivery (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

In the criminal justice area, programs have begun to offer alternatives to incarceration. New legislation establishes an independent police monitor as part of the Inspector General’s Office and new interagency partnerships across the criminal justice system (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

With respect to the coastal wetlands, acknowledged as important for flood protection, the state created the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority. A plan for coastal restoration has also been passed by the state, and the need for better land-use and land-use management plans has been recognized, including the adoption of a statewide building code (Liu and Plyer, 2010). At the federal level, the Obama administration released a roadmap to guide federal efforts to restore coastal ecosystems of Louisiana and Mississippi (see http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/ceq/initiatives/gulfcoast/roadmap; accessed May 30, 2011).

All of these reforms “need a lot more work,” said Plyer, but many were “essentially unimaginable before the storm.”

Remaining Obstacles

Despite this progress, several indicators point to continuing difficulties as New Orleans seeks to recover from Katrina. First, money remains a serious constraint. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita combined caused an estimated $150 billion in damages across the Gulf Coast. The federal government spent an estimated $126 billion on the recovery effort, but much of that money went to such short-term measures as emergency rescue operations and short-term housing. Only about $45 billion of that money went to rebuilding. Private insurance provided about $30 billion for reconstruction, and philanthropies provided about $6 billion—three times as much as for any other event in history. Even with expenditures of that magnitude, a gap of about $70 billion remains (Ahlers et al., 2008). “We are going to see the effects of Katrina in our communities for probably our lifetime because there’s not enough money to rebuild.”

Furthermore, major industries, including oil and gas, and shipping, have all declined since 1980. To some extent, a rise in tourism made up for the loss of jobs in oil and gas, but the number of tourism jobs is now lower than in 1980. The Deepwater Horizon disaster reinforced how vulnerable many industries in the region are to water-related disasters, though the 2010 oil spill provides an opportunity to use some of the funds from BP (British Petroleum) to clean up and restore the wetlands that protect the city.

Also, New Orleans may have lost educated workers after the storm. In 2008 the share of college-educated workers in New Orleans remained unchanged from 2000 at about 23 percent, but this number grew nationally (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

Income disparities remain stark among whites, Hispanics, and African Americans in New Orleans. Black and Hispanic household incomes are 45 and 25 percent lower than for whites, respectively. The New Orleans African American population has even lower household incomes than the national average for African Americans. The suburban parishes now house the majority of the metro-

politan area’s poor (Liu and Plyer, 2010). This trend started before Katrina and is consistent with the national trend of the suburbanization of poverty.

Despite the growth in average wages and median household incomes in the metropolitan area, “renters in the city and suburbs still pay too much of their earnings toward housing” (Liu and Plyer, 2010). In Orleans Parish, 58 percent of renters, and 45 percent of renters in the metropolitan area, pay more than 35 percent of their pretax household income toward housing, compared with 41 percent of renters nationally. Homeowners in New Orleans also bear a higher cost burden than is the average nationwide (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

“Violent crimes and property crimes have risen” since Katrina “and remain above national rates,” (Liu and Plyer, 2010) though they are lower than they were in 1990. The rates for both types of crimes in Orleans Parish are about double the national rates, Plyer said.

Meanwhile, coastal wetlands have continued to erode. More than 23 percent of the land around the New Orleans Metropolitan Area has been lost since measurements began in 1956; the impact of the oil disaster on the wetlands has not yet been measured (Liu and Plyer, 2010).

Principles for Recovery

Much of the recovery since Katrina has been aimed at bringing the city back to where it was before the disaster. But that is not enough, Plyer said. The goal must be transformation, not just preserving the status quo. In this regard, she identified three key principles for continuing the recovery.

The first is to sustain and build on post-Katrina reforms. Specific ideas suggested in Liu and Plyer (2010) include

• Increasing the pool of qualified teachers.

• Providing “sustained gap funding for community-based health centers.”

• Building “capacity within local government to drive … improvements” among criminal justice agencies.

• Not rescinding or reallocating unspent hurricane recovery dollars and rather using those funds to address unmet housing needs, neighborhood rehabilitation, and community capacity.

The second principle is to embrace new opportunities presented by the recession and oil spill. Liu and Plyer (2010) suggest

• Investment in the restoration of coastal wetlands, and advancing the approach to live with water.

• Diversification of the economy, including the energy sector.

• Challenging entrepreneurs to generate creative business ideas that strengthen legacy industries.

• Expanding international export capacity through port modernization and multimodal freight strategies.

• “Increasing the capacity of small businesses, especially minority- and women-owned businesses,” to participate in growth sectors.

The third principle is to strengthen “regional resilience to minimize future shocks and shape the future course” of events (Liu and Plyer, 2010). In this area, Liu and Plyer (2010) suggest that New Orleans should

• Diversify its economy and increase skills.

• “Expand local ‘wealth’ (e.g., tax base, private investment, philanthropy) to match outside resources.”

• “Continue to nurture an open society where engagement, networks, partnerships, and collaborations can evolve organically.”

• “Help maintain citizen participation as the community transitions from ‘crisis’ to implementation.”

Becoming resilient is a marathon and not a sprint, Plyer concluded.

Discussion

During the discussion period, Plyer was asked about her vision for New Orleans in 2050. She responded that New Orleans has tremendous potential to lead in such areas as renewable energies, for example, by redeploying scientists and engineers involved in the oil and gas industries. Sectors of the U.S. economy, such as the military, and entire countries, such as China, have made a commitment to renewable energy, so a market exists. New Orleans culture has not emphasized innovation in the past, but the numbers of entrepreneurs in the city have grown since Katrina. “It’s a matter of industry, will, and intention.”

New Orleans also has the unique advantage of the Mississippi River, which it could use to increase its role in an export economy. The United States has many products that could be sold abroad, and the country needs to reverse its trade imbalances. New Orleans exists because of its port, and reforms to the port’s governance and infrastructure could make the city a vibrant place. “We have allowed other ports to greatly supersede our capacity, like Mobile, Houston, et cetera, but they don’t have the Mississippi River.”

Finally, many new people are moving to New Orleans, which is changing the city’s culture. ”We enjoy Mardi Gras, but we’re going to keep pushing to make it a modern city with a vibrant and future-oriented economy.” Issues of inclusion and equity also need to be addressed as the city’s culture changes, “because we can’t be prosperous unless everybody is prosperous.” Changing the culture is a lot of hard work, but the city already has a culture unlike that of any other city. Building on that culture could create a new future for the city.

In response to a question about the privatization of governmental services, Plyer responded that more evidence is needed to make generalizations that apply across sectors. In some cases the privatization of services in New Orleans after Katrina has had benefits, but in other cases the privatization of services has been tremendously inefficient. It “bends both ways.”

Plyer also said that people in every neighborhood in the city tend to express the opinion that other neighborhoods are receiving more money than is their neighborhood. However, tracking the exact expenditures of recovery funds is very difficult. “Can we say for sure that Lower Nine is getting less than Lakeview? I don’t know that there are any numbers that could show that. What we encourage folks to do is really to continue to build their capacity to advocate for what they need in their neighborhood.”

Finally, in response to a question about climate change, Plyer observed that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been commissioned to build levees that will protect the city against a 100-year storm. But that level of protection will not be adequate in the future. Many people in the city have become interested in the flood protection measures being built in the Netherlands, where protection against an 11,000-year storm is the goal. Pursuing such a goal for New Orleans would require a tremendous effort. “It’s not going to happen overnight, but the folks who understand what it’s going to take for the city to be sustainable will not give up that fight, because folks are not fooled into thinking that the levees will be sufficient.”