2

A Preliminary Classification of Skills and Abilities

This chapter presents an initial classification of skills and abilities, including various terms used to describe “21st century skills.” The committee found this preliminary classification scheme useful in addressing each question in the study charge, and the scheme is used to varying degrees throughout the report. At the same time, the committee hopes that the preliminary scheme proves useful for further research to develop shared definitions of these skills.

THREE DOMAINS OF COMPETENCE

As a first step toward describing 21st century skills, the committee identified three domains of competence: cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal. These three domains represent distinct facets of human thinking and build on previous efforts to identify and organize dimensions of human behavior. For example, Bloom’s 1956 taxonomy of learning objectives included three broad domains: cognitive, affective, and psychomotor. Following Bloom, we view the cognitive domain as involving thinking and related abilities, such as reasoning, problem solving, and memory.1 Our intrapersonal domain, like Bloom’s affective domain, involves emotions and feelings and includes self-regulation—the ability to set and achieve one’s

___________________

1In Bloom’s taxonomy of the cognitive domain, knowledge is at the lowest level (or “order”), with comprehension and application of information above. The higher orders include analysis and synthesis, and the highest level is evaluation (Bloom, 1956). The influence of the taxonomy is seen in current calls for schools to teach “higher-order skills.”

goals (Hoyle and Davisson, 2011). The interpersonal domain we propose is not included in Bloom’s taxonomy but rather is based partly on a recent National Research Council (NRC) workshop that clustered various 21st century skills into the cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal domains (National Research Council, 2011a). In that workshop, Bedwell, Fiore, and Salas (2011) proposed that interpersonal competencies are those used both to express information to others and to interpret others’ messages (both verbal and nonverbal) and respond appropriately.

Distinctions among the three domains are reflected in how they are delineated, studied, and measured. In the cognitive domain, knowledge and skills are typically measured with tests of general cognitive ability (also referred to as g or IQ) or with more specific tests focusing on school subjects or work-related content. Research on intrapersonal and interpersonal competencies often uses measures of broad personality traits (discussed further below) or of child temperament (general behavioral tendencies, such as attention or shyness). Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists studying mental disorders use various measures to understand the negative dimensions of the intrapersonal and interpersonal domains (Almlund et al., 2011).

Although we differentiate the three domains for the purpose of understanding and organizing 21st century skills, we recognize that they are intertwined in human development and learning. Research on teaching and learning has begun to illuminate how intrapersonal and intrapersonal skills support learning of academic content (e.g., National Research Council, 1999) and how to develop these valuable supporting skills (e.g., Yeager and Walton, 2011). For example, we now know that learning is enhanced by the intrapersonal skills used to reflect on one’s learning and adjust learning strategies accordingly—a process called “metacognition” (National Research Council, 2001; Hoyle and Davisson, 2011). At the same time research has shown that the development of cognitive skills, such as the ability to stop and think objectively about a disagreement with another person, can increase positive interpersonal skills and reduce antisocial behavior (Durlak et al., 2011). And the interpersonal skill of effective communication is supported by the cognitive skills used to process and interpret complex verbal and nonverbal messages and formulate and express appropriate responses (Bedwell, Fiore, and Salas, 2011).

A DIFFERENTIAL PERSPECTIVE ON 21st CENTURY SKILLS

To address our charge to define 21st century skills and describe how they relate to each other, we turn to the research in differential psychology. This research has focused on understanding human behavior by examining systematic ways in which individuals vary and by using relatively stable patterns of individual differences as the basis for structural theories of

cognition and personality. Much of this work is rooted in efforts to identify and define skills and competencies through a process of measurement, with inferences drawn about the significance and breadth of a construct by analyzing patterns of correlations.

We view 21st century skills as knowledge that can be transferred or applied in new situations. This transferable knowledge includes both content knowledge in a domain and also procedural knowledge of how, why, and when to apply this knowledge to answer questions and solve problems. The latter dimensions of transferable knowledge (how, why, and when to apply content knowledge) are often called “skills.” We refer to this blend of content knowledge and related skills as “21st century competencies.” In Chapter 4, we propose that deeper learning is the process through which such transferable knowledge (i.e., 21st century competencies) develops.

Our use of “competencies” reflects the terminology used by the OECD in its extensive project to identify key competencies required for life and work in the current era. According to the OECD (2005), a competency is

more than just knowledge and skills. It involves the ability to meet complex demands, by drawing on and mobilizing psychosocial resources (including skills and attitudes) in a particular context. For example, the ability to communicate effectively is a competency that may draw on an individual’s knowledge of language, practical IT skills, and attitudes towards those with whom he or she is communicating. (OECD, 2005, p. 4)

Differential psychology has traditionally focused on identifying characteristics of individuals, including general cognitive ability and personality traits, that are thought to persist throughout an individual’s life. In contrast, the committee views cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal competencies as malleable and subject to change in response to life experience, education, and interventions. In the cognitive domain, for example, the view of intelligence as a single, unitary ability that changes little over a lifetime has been superseded by research indicating that intelligence includes multiple dimensions (Carroll, 1993) and that these dimensions change over time. Horn (1970) found that fluid intelligence (a construct that includes verbal and quantitative reasoning abilities) decreases from adolescence to middle age, while crystallized intelligence (accumulated skills, such as verbal comprehension and listening ability) increases over the same period. McArdle et al. (2000) observed similar patterns of change, finding that fluid intelligence tended to peak in very early adulthood and then to decline, while crystallized intelligence tended to increase over the life cycle. Findings from a series of studies conducted over four decades, summarized by Almlund et al. (2011), indicate that how well individuals perform on intelligence tests is influenced not only by cognitive abilities but also by how much effort they exert, reflecting their motivation and related intrapersonal competencies.

This growing body of evidence showing that dimensions of intelligence are malleable has important implications for teaching and learning. Recent research on interventions designed to increase motivation has found that a learner who views intelligence as changeable through effort is more likely to exert effort in studying (Yaeger and Walton, 2011; see further discussion in Chapter 4).

In the intrapersonal and interpersonal domains, Roberts, Walton, and Viechtbauer (2006) found that both the intrapersonal competency of conscientiousness (sometimes called self-direction or self-management in lists of 21st century skills) and the interpersonal competency of social assertiveness increase with age. Srivastava et al. (2003) analyzed data from the “big five” personality inventories completed by a large sample of over 130,000 adults, finding that both conscientiousness and the interpersonal skill of agreeableness increased throughout early and middle adulthood. The authors also found that neuroticism declined with age among women, but not among men. Reflecting on these various patterns of change, Srivastava et al. (2003) concluded that personality traits are complex and subject to a variety of developmental influences.

In contrast to the prevailing view of personality traits as fixed, some researchers have argued that individual human behavior demonstrates no consistent patterns and instead changes continually in response to various situations (e.g., Mischel, 1968). Based on a review of the research related to both points of view, Almlund and colleagues concluded that “although personality traits are not merely situation-driven ephemera, they are also not set in stone,” and suggested that these traits can be altered by experience, education, parental investments, and targeted interventions (Almlund et al., 2011, p. 9). They proposed that interventions to change personality are promising avenues for reducing poverty and educational disadvantage.

With this view of malleability in mind, the committee reviewed lists of 21st century skills included in eight recent reports and papers (see Appendix B). We selected reports and papers for review if they built on, synthesized, or analyzed previous work on 21st century skills. For example, we included a report that reviewed 59 international papers on 21st century skills and found that the skills most frequently referred to were collaboration, communication, information and communications technology (ICT) literacy, and social or cultural competencies (Voogt and Pareja Roblin, 2010). We selected a white paper commissioned by the Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills project that synthesized many previous lists of 21st century skills and organized them into a taxonomy of skills (Binkley et al., 2010). We also included a document from the Hewlett Foundation that lists 15 skills based on previous research by the OECD (Ananiadou and Claro, 2009). In addition, we included papers commissioned by the NRC to more clearly define 21st century skills (e.g., Finegold and Notabartolo,

2010; Hoyle and Davisson, 2011) and a list of college outcomes developed by Oswald and colleagues (2004) based on an analysis of college mission statements.

The reports and papers on 21st century skills used different language to describe the same construct, an instance of the “jangle fallacy” (Coleman and Cureton, 1954). Early in the history of mental measurement, Kelly (1927) observed that investigators sometimes used different measures—and the names associated with these measures—to study and describe a single psychological construct or competency. This problem, which he referred to as the “jangle fallacy,” caused waste of scientific resources, as multiple tests were used to study the same construct, and investigators who used one measure to study the construct sometimes ignored the research results of other investigators who used other measures to study the same construct. Today measurement experts continue to struggle with the question of whether various constructs represent different names for the same underlying psychological phenomenon or are truly different dimensions of human competence. A 2002 paper, for example, addressed the question of whether separate measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy were in fact focusing on a single core construct (Judge et al., 2002). The committee identified the “jangle fallacy” in reports that listed, for example, both teamwork and collaboration and both flexibility and adaptability as individual 21st century skills (see Appendix A).

To address this problem, the committee clustered various terms for 21st century skills around a small number of constructs, creating a preliminary taxonomy that may be useful in future research. To identify this small number of constructs, we turned to extant taxonomies of human abilities that have a solid basis in the differential psychology research. Research-based taxonomies are available covering both cognitive (Carroll, 1993) and noncognitive (Goldberg, 1992) competencies. Based on a content analysis, we assigned different 21st century skills from the recent reports into domains within those taxonomies. In addition, we compared the recent reports with earlier reports on workplace skill demands, including the Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills (SCANS) report (1991) and the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) report (Peterson et al., 1997).

Skills as Latent Variables and Two Kinds of Latent Variables

It is useful to differentiate between a construct, such as a competency, and its measurement. Social scientists and human resource managers routinely measure a competency, such as leadership, in a variety of ways, ranging from a self-report Likert scale to a workplace performance appraisal or an inbox test. Separating the construct from its measurement is valuable conceptually because a construct may be important even if its measurement

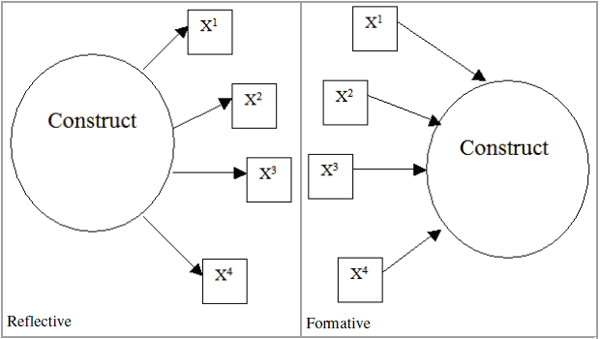

is poor. In psychometric modeling, constructs viewed as separate from their measures are referred to as latent (as opposed to observed or measured) variables. There are two types of latent variables: reflective latent variables and formative latent variables (see Figure 2-1).

Following a concept proposed by Spearman (1904, 1927), a reflective latent variable is identified based on correlations among scores from a set of tasks. Differential psychologists discover reflective latent variables using factor analysis and related methods to identify the patterns of correlations among a set of “indicator variables”—scores on tests and rating instruments used to measure cognitive and noncognitive competencies. A reflective latent variable—such as general cognitive ability or one of the “big five” personality factors (McCrae and Costa, 1987)—is thought to reflect the essence of, or the commonality among, the various competencies measured. In psychometric modeling, a reflective latent variable (also called a factor because it is discovered through factor analysis) is said to cause the relationships among the set of indicator variables (see Figure 2-1). For example, extraversion, a personality factor, is thought to cause relatively high scores on instruments measuring warmth, gregariousness, and assertiveness. Within a reflective latent variable, the importance or weighting of an individual indicator variable is a function of how highly that particular indicator variable correlates with other indicator variables for the reflective latent variable (Bollen and Lennox, 1991).

FIGURE 2-1 Casual structures in reflective and formative latent variables.

SOURCE: Stenner, Burdick, and Stone (2008). Reprinted with permission.

A formative latent variable is very different from a reflective latent variable in that the direction of causality runs from the observed indicator variable to the formative latent variable. The indicator variables may be positively correlated, uncorrelated, or even negatively correlated, and patterns of correlations among them are not used to identify formative latent variables. Instead, experts identify formative latent variables through a variety of other means, such as through consensus opinion or traditions in a field. Formative latent variables can be thought of as a “stew”—a mixture of elements that might or might not be related. The various lists of 21st century skills that have been proposed to date are formative variables, identified by consensus opinion and through reviews of earlier reports and standards documents (e.g., Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills, 1991; American Association of School Libararians and Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 1998).

Reflective Latent Variables:

Taxonomies of Cognitive and Noncognitive Competencies

Because reflective latent variables (factors) are based on empirical research, they provide a strong framework for organizing the formative variables included in lists of 21st century skills. Taxonomies of reflective latent variables are available for both cognitive (Carroll, 1993) and noncognitive (Goldberg, 1992) competencies.

Cognitive Abilities Taxonomy

Carroll (1993) conducted a secondary analysis of over 450 correlation matrices of cognitive test scores that had been produced between 1900 and 1990. He sought to identify a common structure to characterize the pattern of correlations among tests and thereby to identify the factors of human cognition. He found that the data were consistent with a “three stratum” hierarchical model with a general cognitive ability factor at the top, eight second-order abilities (factors) at the middle level, and 45 primary abilities at the bottom of the taxonomy. The second-order factors identified were as follows (with the corresponding primary abilities shown in parentheses):

- Fluid intelligence (reasoning, induction, quantitative reasoning, and Piagetian reasoning, a collection of abstract reasoning abilities described in Piaget’s 1963 theory of cognitive development, such as the ability to organize materials that possess similar characteristics into categories and an awareness that physical quantities do not change in amount when altered in appearance)

- Crystallized intelligence (verbal comprehension, foreign language aptitude, communication ability, listening ability, and the ability to provide missing words in a portion of text)

- Retrieval ability (originality/creativity, the ability to generate ideas, and fluency of expression in writing and drawing)

- Memory and learning (memory span, recall by association, free recall, visual memory, and learning ability)

- Broad visual perception (visualization, spatial relations, speed in perceiving and comparing images, and mental processing of images)

- Broad auditory perception (hearing and speech, sound discrimination, and memory for sound patterns)

- Broad cognitive speediness (rate of test taking [tempo] and facility with numbers)

- Reaction time (computer) (simple reaction time to respond to a stimulus, reaction time to choose and make an appropriate response to a stimulus, and semantic retrieval of general knowledge)

We focused the content analysis on the first three factors—fluid intelligence, crystallized intelligence, and retrieval ability—because the primary abilities they included were most closely related to the 21st century skills discussed in the reports and documents. It is important to note that our content analysis did not address how valuable any of the 21st century skills may be for influencing later success in employment, education, or other life arenas. To carry out the content analysis we simply took lists of competencies that other individuals and groups have proposed are valuable and aligned them with research-based taxonomies of cognitive and noncognitive competencies. In the following chapter, we discuss research on the relationship between various competencies and later education and employment outcomes.

Personality Taxonomy

For the past two decades, the “big five” model of personality has been widely accepted as a way to characterize competencies in the interpersonal and intrapersonal domains (McCrae and Costa, 1987; Goldberg, 1993). It is based on the lexical hypothesis, which suggests that language evolves to characterize the most salient dimensions of human behavior, and so by analyzing language and the way we use it to describe ourselves or others it is possible to identify the fundamental ways in which people differ from one another (Allport and Odbert, 1936). Based on a review of English dictionaries, psychologists identified personality-describing adjectives and developed many instruments to measure these characteristics. Multiple,

independent factor–analytic studies of scores on these instruments, using different samples, converged on five personality factors (Almlund et al., 2011).

This taxonomy has been replicated in many languages, yielding approximately the same five dimensions,2 defined as follows (American Psychological Association, 2007):

- Openness to experience: the tendency to be open to new aesthetic, cultural, or intellectual experiences

- Conscientiousness: the tendency to be organized, responsible, and hardworking

- Extroversion: an orientation of one’s interests and energies toward the outer world of people and things rather than toward the inner world of subjective experience

- Agreeableness: the tendency to act in a cooperative, unselfish manner

- Neuroticism: a chronic level of emotional instability and proneness to psychological distress. The opposite of neuroticism is emotional stability, defined as predictability and consistency in emotional reactions, with absence of rapid mood changes.

Reflecting the fact that they were derived from factor analysis, the five factors are intended to be orthogonal, or uncorrelated with one another. Each can be broken down further into personality facets, which are sets of intercorrelated factors. Facets are not as stable across cultures as the major five dimensions are, but they nevertheless prove useful ways to characterize individual differences more precisely (Paunonen and Ashton, 2001). When various proposals for facets are combined with the five factors, the result is a hierarchical taxonomy. Although no clear consensus has emerged on exactly which facets should be used to further characterize the five personality dimensions, the facets suggested by Costa and McCrae (1992) are widely used and are presented here to illustrate the range of individual characteristics encompassed by each of the five factors:

- Conscientiousness (competence, order, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, deliberation)

- Agreeableness (trust, straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, modesty, tender-mindedness)

- Neuroticism (anxiety, angry hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsiveness, vulnerability)

___________________

2Some languages identify a sixth factor related to honesty (e.g., Ashton, Lee, and Son, 2000).

- Extroversion (warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement seeking, positive emotions)

- Openness to experience (fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, actions, ideas, values)

To the facets of the neuroticism/emotional stability factor proposed by Costa and McCrae (1992) we added “core self-evaluation,” based on a proposal by Judge and Bono (2001). This additional proposed construct is based on empirical findings of correlations between measures of self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control,3 and emotional stability. Almlund et al. (2011) also found that self-esteem and locus of control are related to emotional stability.

The five major factors provided a small number of research-based constructs onto which various terms for 21st century skills could be mapped. The facets helped to define the range of skills and behaviors encompassed within each major factor to serve as a point of comparison with the various 21st century skills.

Formative Latent Variables: Occupational Skills and Other Examples

Unlike reflective latent variables that are discovered, formative latent variables are constructed. Relationships between variables do not constrain the development of formative latent variables; rather, formative latent variables can be whatever a person or community defines them to be. Classic examples appear in economics, such as the consumer price index; in health, such as the stress index; and in business research, such as leadership or positive experience with a product (Jarvis, Mackenzie, and Podsakoff, 2003).

One set of formative latent variables that may be particularly relevant for defining 21st century competencies was identified through expert consensus in the O*NET project (Peterson et al., 1999). O*NET is a large database of information on 965 occupations that is organized around a “content model,” which describes occupations along several dimensions, including worker characteristics (abilities, interests, work values, and work styles) and requirements (skills, knowledge, and education). The skills included in the O*NET content model are similar to those in current lists of 21st century lists, as shown in Table 2-1.

___________________

3In differential psychology, locus of control refers to the extent to which individuals believe that they can control their own lives (an internal locus of control) or that outside influences control what happens (an external locus of control), as measured by the Rotter scale (Rotter, 1990). The “locus of control” construct has been criticized as being too general, and most researchers currently differentiate beliefs about causality as delineated in attribution theory.

TABLE 2-1 Skills in the O*NET Content Model

| Basic Skills | ||

| Content Skills | Process Skills | |

| Active listening | Active learning | |

| Reading comprehension | Learning strategies | |

| Writing | Monitoring | |

| Speaking | Critical thinking | |

| Mathematics | ||

| Science | ||

| Cross-Functional Skills | ||

| Complex Problem Solving | Social Skills | |

| Complex problem solving | Social perceptiveness | |

| Coordination | ||

| Persuasion | ||

| Negotiation | ||

| Instruction | ||

| Service orientation | ||

|

Technical Skills Operations analysis Technology design Equipment selection Installation Programming Quality control analysis Operation monitoring Equipment maintenance Troubleshooting Repairing Resource Management Skills Time management Management of financial resources Managing material resources Managing personnel resources |

|

Systems Skills Systems analysis Judgment and decision making Systems evaluation |

SOURCE: Adapted from Peterson et al. (1997). Copyright 1999 by the American Psychological Association. Reproduced with permission. The use of APA information does not imply endorsement by APA.

Aligning Lists of 21st Century Skills with Ability and Personality Factors

As a first step toward aligning various lists of competencies included in the reports and documents on 21st century skills with ability and personality factors, the committee compared the eight reports and documents mentioned above, identifying areas of overlap and differences. Another useful step was to divide the various competencies into the three domains

TABLE 2-2 Clusters of 21st Century Competencies

| Cluster | Terms Used for 21st Century Skills | O*NET Skills | Main Ability/ Personality Factor | |||

| COGNITIVE COMPETENCIES | Cognitive Processes and Strategies | Critical thinking, problem solving, analysis, reasoning/argumentation, interpretation, decision making, adaptive learning, executive function | System skills, process skills, complex problem-solving skills | Main ability factor: fluid intelligence (Gf) | ||

| Knowledge | Information literacy (research using evidence and recognizing bias in sources); information and communications technology literacy; oral and written communication; active listening | Content skills | Main ability factor: crystallized intelligence (Gc) | |||

| Creativity | Creativity, innovation | Complex problem-solving skills (idea generation) | Main ability factor: general retrieval ability (Gr) | |||

| INTRAPERSONAL COMPETENCIES | Intellectual Openness | Flexibility, adaptability, artistic and cultural appreciation, personal and social responsibility (including cultural awareness and competence), appreciation for diversity, adaptability, continuous learning, intellectual interest and curiosity | [none] | Main personality factor: openness | ||

| Work Ethic/ Conscientiousness | Initiative, self-direction, responsibility, perseverance, productivity, grit, Type 1 self-regulation (metacognitive skills, including forethought, performance, and self-reflection), professionalism/ ethics, integrity, citizenship, career orientation | [none] | Main personality factor: conscientiousness | |||

| Positive Core Self-Evaluation | Type 2 self-regulation (self-monitoring, self-evaluation, self-reinforcement), physical and psychological health | [none] | Main personality factor: emotional stability (opposite end of the continuum from neuroticism) |

| Cluster | Terms Used for 21st Century Skills | O*NET Skills | Main Ability/ Personality Factor | |||

| INTERPERSONAL COMPETENCIES | Teamwork and Collaboration | Communication, collaboration, teamwork, cooperation, coordination, interpersonal skills, empathy/perspective taking, trust, service orientation, conflict resolution, negotiation | Social skills | Main personality factor: agreeableness | ||

| Leadership | Leadership, responsibility, assertive communication, self-presentation, social influence with others | Social skills (persuasion) | Main personality factor: extroversion | |||

SOURCE: Created by committee.

of cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal competence. Using this approach we found that some of the documents that dealt with 21st century skills focused primarily on one category. For example, Conley’s 2007 list of college readiness skills deals mainly with cognitive competencies, while Hoyle and Davisson’s 2011 analysis of self-regulation focuses on intrapersonal competencies.

Next, the committee conducted a content analysis, comparing the various competencies included in the eight documents with the reflective latent variables at the top of the cognitive abilities and personality taxonomies. Based on the comparative content analysis, we aligned the various 21st century skills with each other and with the two taxonomies. In addition, we also aligned O*NET skills and additional noncognitive competencies with the two taxonomies. Through these steps we created clusters of closely related competencies within each of the three broad domains (see Table 2-2). Each competency cluster contains the main factor (personality or ability) and the associated 21st century skills and O*NET skills. The result is a preliminary taxonomy of 21st century competencies, which we offer as a starting point for further research.

Based on the committee’s content analysis, some of the competencies that appeared in the eight documents and reports were not included in any of the clusters. These included life and career skills (Binkley et al., 2010), social and cultural competencies (Voogt and Pareja Roblin, 2010), study skills and contextual skills (Conley, 2007), and nonverbal communication and intercultural sensitivity (Bedwell, Fiore, and Salas, 2011). These particular competencies were excluded because they did not align well with any of the clusters, rather than because of any judgment that they were less valuable for later life outcomes. In the following chapter, we discuss the question of whether various competencies predict success in education, the workplace, or other areas of adult life.

We offer the proposed taxonomy of competency clusters as an initial step toward addressing the “jangle fallacy.” It provides a starting point for further research that may more clearly define each construct and establish its relationship with the other constructs. However, research to date on the importance of 21st century competencies uses a variety of terms for these skills, coined by investigators in the different disciplines. Our review of this research in the following chapter reflects this variety of terms.

SUMMARY

Although many lists of 21st century skills have been proposed, there is considerable overlap among them. Many of the constructs included in such lists trace back to the original SCANS report (Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills, 1991), and some now appear in the O*NET

database. Aligning the various competencies with extant, research-based personality and ability taxonomies illuminates the relationships between them and suggests a preliminary new taxonomy of 21st century competencies. Much further research is needed to more clearly define the competencies at each level of the proposed taxonomy, to understand the extent to which various competencies and competency clusters may be malleable, to elucidate the relationships among the competencies, and to identify the most effective ways to teach and learn these competencies.