4

Lessons on Financing Investments from India

INVESTING IN YOUNG CHILDREN: INDIA’S EXPERIENCE1

Subrat Das and Protiva Kundu of the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability gave a presentation on India’s investment in young children and opened their talk by noting that India’s birth-to-age-6 population is larger than the total population of some other countries and makes up almost 13 percent of the national population (Ministry of Home Affairs, 2011; UNICEF, 2012). Responsibility for 158 million children poses unique budgetary challenges for the government of India and has numerous implications with regard to policy and budget priorities. It is in this context that Das and Kundu framed their presentation.

Because policies in India disaggregate the child population into different age categories, said Das, some age groups have better coverage than others. In addition, he asserted that maternal health is not as prioritized as it should be. This has led to alarming maternal and child health indicators. For example, the infant mortality rate in India is high nationally and uneven across states (Ministry of Home Affairs, 2012). The child-sex ratio of women to men is another area of concern, with a constant decline across the country since 1961, and indicators on malnutrition show limited investment in interventions for young children (International Institute for Population Science and Macro International, 2007). Das noted that two reasons for this underinvestment are the poor alignment of financing

______________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Subrat Das and Protiva Kundu, Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability.

at the government level and the lack of coordination among the different departments and their programming. He also mentioned that the schemes are limited and fail to address the interconnectedness of women’s needs and rights and those of young children. He gave the example of a housing project for urban poor that was intended to give preference to women with children, but failed to be implemented properly.

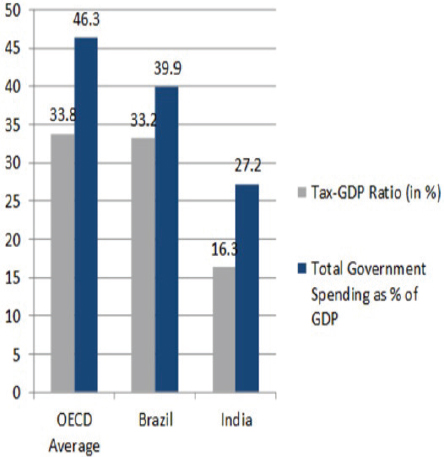

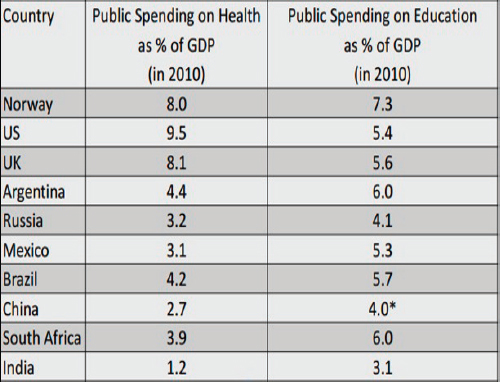

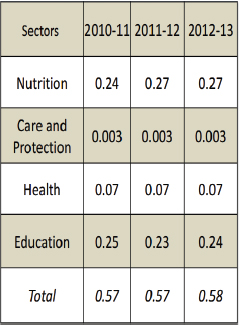

Das highlighted one essential challenge to implementing and funding policies for child development—the low magnitude of public resources available in India, or what Das termed a “limited fiscal policy space.” Gross domestic product (GDP), he said, captures total spending by government, households, and companies, and when a government has a larger fiscal policy space, it is able to spend more on public services. Compared to other large countries with rapid economic growth (also known as BRICSAM countries) and countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), India’s total spending as a percentage of GDP has remained low (see Figures 4-1 and 4-2).2 In 2010, for example, Brazil’s total spending was close to 40 percent, whereas India’s was at 27 percent. Also in 2010, India spent 1.2 percent of GDP on health and 3.1 percent of GDP on education when other countries such as Argentina spent 4.4 percent and 6.0 percent, respectively, and Norway spent a remarkable 8.0 percent on health and 7.3 percent on education. In addition, while other countries’ fiscal policy trajectories show ever-increasing expenditures as a percentage of GDP, India’s has been fairly stagnant (see Figure 4-3; OECD, 2014). One reason for this, Das noted, is a limited capacity for tax revenue as a result of a low tax–GDP ratio. Das argued that India should follow in the footsteps of other rapidly developing economies in increasing tax revenue in order to finance social priorities. Some effort toward this has been made—social sector spending has increased from 5 to 7 percent in the past 10 years, but India still ranks in the bottom 10 countries in terms of public spending on health and education (UNDP, 2013). Das acknowledged that funding for early childhood development programs and services comprises 4 percent of the central government budget, or about 0.6 percent of GDP (Ministry of Finance, 2013a) and noted that several programs supporting early childhood development funded by this allocation are underresourced, with health in particular severely lacking investment.

While increased funding can go a long way in providing services, Das made clear that more money does not directly translate to better outcomes and that governments should seek to improve the quality of services.

______________

2 This information was compiled by the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA) from the International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2014.

FIGURE 4-1 Limited fiscal policy space in India.

NOTE: Figures in the chart are for 2010 and are compiled by Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA) from (1) OECD (2014), “Total tax revenue,” in OECD Factbook 2014: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics, OECD Publishing. (2) OECD (2014), “Government expenditures, revenues and deficits,” in OECD Factbook 2014: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics, OECD Publishing. (3) IMF (2014), “World Economic Outlook—Recovery Strengthens, Remains Uneven,” April 2014. (4) Government of India (2013), “Indian Public Finance Statistics 2012-13,” Ministry of Finance, 2013b.

SOURCE: Das and Kundu, 2014.

At the same time, even if unit costs could be determined on the basis of quality, these costs would differ across the country because of local contextual factors. Proper allocation of resources for child development, then, requires a commitment on the part of the states, too. Das asserted that at both the central government and state government levels, these initiatives are underresourced, lacking adequate staff, training, and materials, and underfinanced, lacking funds to provide high-quality services.

FIGURE 4-2 Public spending on health and education: An international comparison.

NOTE: Compiled from UNDP (2013), Human Development Report 2013.

* Figure for China is from UN database (http://data.un.org).

SOURCE: Das and Kundu, 2014.

Looking at the ICDS in particular, Das noted a number of gaps in service that indicated a failure to adequately finance the national program. As mentioned by others in the workshop, not only are there staff shortages in the Anganwadi centers but also the existing staff is underpaid. In addition, there is a shortage in program management staff, such as project officers and supervisors. In an assessment completed in a few districts across India (CBGA and UNICEF, 2012), Das and his team noted that monitoring and supervision of services is not done because there are no resources to hire such finance and accounting staff. Because there are few supervisors on staff, the child development officers themselves take on a number of tasks meant for other positions and cannot sometimes fulfill their own duties.

Another challenge raised by Das is the underutilization of resources. As noted by other speakers, funding flows often get blocked, and resources fail to reach their recipients. Poor utilization of resources is

FIGURE 4-3 Spending on young children as a percentage of India’s GDP.

NOTE: Compiled from Union Budget, Expenditure Budget, Vol. II, various years; and Economic Survey, Government of India, various years.

SOURCE: Das and Kundu, 2014.

another issue, with funds not always being spent efficiently. In the case of the ICDS, there is unequal spending across regions and through the fiscal year. Das found that utilization is higher at district headquarters, but lower in centers that are farther away, a problem exacerbated by a lack of infrastructure. In addition, Das added, there is a widespread perception of corruption within the scheme. He noted, however, that it is very difficult to prove corruption and that the perception of corruption is not enough to promote change in the government. Social audits, public hearings, and other actions by the court are necessary to prove wrongdoing, and such actions often lie outside the scope of many organizations. To address corruption, Das suggested that there should be greater effort to make budgeting and expenditure more transparent. Although locally relevant budget information is collected, it is not released to the public. Rather, the information is aggregated and presented at the national level. Das asserted that this information should instead remain local and disseminated to better understand the nuances within specific centers and districts.

In the discussion that took place after the presentation, Das and Kundu reiterated that simply increasing funding would not necessarily improve the quality of services. Improving infrastructure and resolving

leakage of funds are also important. But given shortages in staff, one possible approach is to first increase expenditures and then begin to assess the various components of programs. In response to another question about human resources shortages, Kundu noted that training is not necessarily something that is prioritized in budgeting. There are sometimes adequate numbers of people receiving the required training, but the training itself is not always adequate for the job duties required. When queried about the value of budget analysis on policy making, Das acknowledged that although information regarding gaps in funding and service provision can be highlighted, it will not necessarily create any sense of urgency on the part of policy makers. It is necessary to convince and empower government officials to take ownership of the issue.

In his discussion, Bose explained that a pattern has emerged: civil society movements pushed the courts to actively establish general principles of governance for the best interests of society, efforts which were taken up by the central government in a series of legislation that led to expanded and sustainable financing of early childhood development programs. He emphasized that not only did the courts recognize certain rights but also the government acted to uphold those rights. This pressure resulted in yearly budget increases for child welfare schemes, to 810 billion rupees today.

Bose also highlighted the need for transparency in budgeting—central government expenditures on children are part of the national budget, providing a template for state governments to follow in their own financing. In addition, such transparency allows for examination by external parties. He noted that some criticism has arisen around what is a nominal increase in funding but a decline relative to India’s GDP. Therefore, the same civil society pressure that brought forth these schemes initially could also be used to ensure sustained increases in funding over time.

At the state government level, Bose described the situation in the state of Madhya Pradesh. Ten to 15 years ago, social spending dropped in a number of states because of fiscal crises. In response, the 12th Finance Commission recommended transfers through states to fund programs, as well as debt consolidation schemes. In addition, many states replaced sales tax with value-added tax, which buoyed up revenues. Because of these measures, Madhya Pradesh was able to increase spending on children’s programs and is currently one of the few states where the state’s own contribution exceeds that of the central government. Bose noted that the adoption of fiscal responsibility legislation proved helpful in this state. Rather than decreasing spending, it resulted in better management of finances and, in turn, higher expenditures on social services.