9

Health Status and Access to Care

The health of immigrants and its implications for American society have long been discussed, commented on, and at times, hotly contested. In the early part of the 20th century, immigrants were portrayed as sickly, likely to transmit infectious diseases, and a burden to local governments (Markel and Stern, 1999). Research eventually showed that infectious diseases had less to do with immigration and more to do with the neighborhood conditions, where immigrants frequently resided in cramped, crowded tenements with unsafe drinking water and unsanitary sewage removal systems (Garb, 2003). More recently, another picture has emerged that depicts immigrants from some countries as healthier and hardier than U.S.-born residents and less likely to access health care (Derose et al., 2007; Jasso et al., 2004; Paloni and Arias, 2004).

This chapter provides a summary review of some of the key evidence about the health status of immigrants and their capacity to access health care. The chapter (a) compares the rates of mortality and morbidity outcomes between immigrants and the native-born; (b) describes the association between some dimensions of immigrant integration and health; (c) focuses on the disparities in health care access between immigrants and the native-born, with an emphasis on health insurance coverage; (d) discusses the Patient Protection andAffordable Care Act (ACA) and its consequences for immigrants; and (e) identifies some future issues that may affect the health and well-being of immigrants.

HEALTH AND ILLNESS AMONG IMMIGRANTS

Comprehensive analyses on immigrant health status using eight federal national datasets1 show that immigrants have better infant, child, and adult health outcomes than the native-born in general and the native-born members of the same ethnoracial groups (Singh et al., 2013). Immigrants, compared to the native-born, are less likely to die from cardiovascular disease and all cancers combined and have a lower incidence of all cancers combined, fewer chronic health conditions, lower infant mortality rates, lower rates of obesity, lower percentages who are overweight, fewer functional limitations, and fewer learning disabilities. Other studies show that immigrants have lower prevalence of depression, the most common mental disorder in the world, and alcohol abuse than the native-born (Alegria et al., 2007a; Brown et al., 2005; Szaflarski et al., 2011; Takeuchi et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2007).

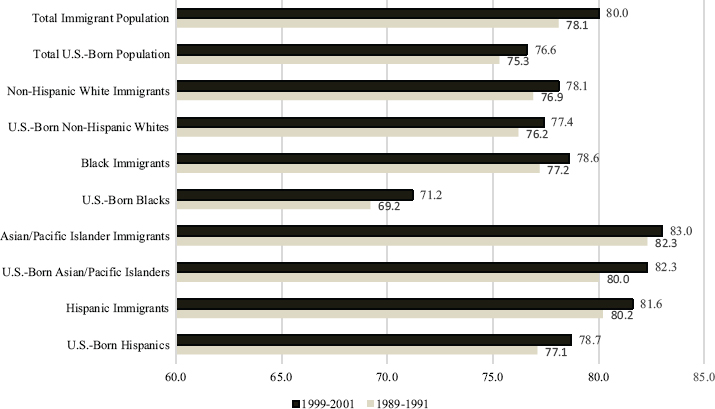

Another example of the difference between immigrants and the native-born in health is life expectancy. Life expectancy is a widely used summary indicator that gauges the health of a population or group using a measure of the number of years a person is expected to live based on mortality statistics for a given time period. In one example of relevant research (Singh et al., 2013), national birth and death records were linked to provide life expectancy data. The data were reported for people living in 1999-2001 and included death records up to 2010, adjusted for age and gender. This study found that immigrants had a life expectancy of 80.0 years, which was 3.4 years higher than the native-born population (see Figure 9-1). Across the major ethnic categories (non-Hispanic whites, blacks, Asian/Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics), immigrants showed a life expectancy advantage over their native-born counterparts. This life expectancy advantage for immigrants over the native-born ranges from 0.7 years for whites and Asian/ Pacific Islanders to a high of 7.4 years for blacks. The immigrant life expectancy advantage is comparable to that reported for an earlier time period (1989-1991) (Singh et al., 2013).

This pattern does not suggest that immigrants are free from infectious diseases, chronic illnesses, disabilities, mental disorders, or other health problems, but rather they show a general health advantage when compared to the native-born. Some exceptions are evident to this overall pattern. Immigrant males and females, for example, were more likely to die from stomach and liver cancer than native-born males and females (Singh et

___________________

1 The datasets used in the research discussed here include the American Community Survey, National Health Interview Survey, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, National Linked Birth and Infant Death Files, National Longitudinal Mortality Study, National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, National Survey of Children’s Health, and National Vital Statistics Systems.

SOURCE: Data from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System, 1989-2001; Singh et al. (2013).

al., 2013). Chinese, Mexican, and Cuban immigrants were more likely to report their children’s health as poor/fair compared to their native-born counterparts. Asian Indian, Central American, Chinese, Cuban, Mexican, and South American immigrants reported higher levels of poor/fair health in contrast to native born co-ethnics (Singh et al., 2013). It is also possible that some health problems among recent immigrants, such as diabetes, are not properly diagnosed (Barcellos et al., 2012).

There is only limited research on elderly immigrants and the interaction among immigrant status, age, and health. Elderly immigrants compose a heterogeneous group, and more research about how they age and their subsequent health care needs is essential to inform future policies and programs. One example of the research available is a study of the elderly who worked in low skilled jobs. Hayward and colleagues (2014) found that both foreign-born and native-born Hispanics have lower mortality rates but higher disability rates than non-Hispanic whites; their disability rates are similar to the rates of non-Hispanic blacks. The researchers concluded Hispanics, including the foreign-born, will have an extended period of disability in their elder years. Similarly, Gurak and Kritz (2013) found that older Mexican immigrants in rural areas had twice as many health limitations as other immigrants. It is likely that manual labor leads to functional limitations and disability in later life, and elderly immigrants may have

high demand for health care in their elderly years (Population Reference Bureau, 2013).

The legal status of immigrants is also associated with health status (Landale et al, 2015b). Naturalized immigrants do better than noncitizen inmmigrants on some mobility measures such as acquiring higher levels of education, better paying jobs, and living in safer and better resourced neighborhoods (Aguirre and Saenz, 2002; Bloemraad, 2000; Gonzalez-Barrera et al., 2013). Gubernskaya and colleagues (2013) also found that naturalization has a differential association with health depending on the age of immigration. Among immigrants who came as children and young adults, naturalized citizens had better functional health at older ages than noncitizens. Conversely, among immigrants who came to the United States at middle or older ages, naturalized citizens fared worse on functional health measures than noncitizens. While the precise reasons for this differential effect cannot be determined from the datasets used in the analyses, the authors suggested that naturalization at later stages of life may not confer social and political integration advantages that are positive factors for better health outcomes.

Refugees, unlike immigrants in general, are leaving their home country because they face persecution, and are often escaping wars or political turmoil. People can apply for and receive refugee status if they meet two essential criteria: (1) they are unable or unwilling to return to their home country because of past persecution or fear of persecution and (2) the reason for persecution is associated with race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. After 1 year, refugees must apply for a green card. The circumstances under which refugees exit their home country are associated with trauma, extreme stress, hunger, and living in cramped unsanitary conditions, especially in refugee camps and prior to settling in the United States. It is not surprising that studies find that refugees tend to have relatively high levels of different health problems related to major depression, general anxiety, panic attacks, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Birman et al., 2008; Carswell et al., 2011; Hollifield et al., 2002; Keyes, 2000; Lustig et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2014). A recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) report, for example, found that the estimated age-adjusted suicide rate among Butanese refugees resettled in the United States was 24.4 per 100,000, which is higher than the annual global suicide rate for all persons (16.0 per 100,000) and the annual suicide rates of U.S. residents (12.4 per 100,000).

The health of undocumented immigrants is more difficult to assess than immigrants as a whole because their legal status is generally not available on health administrative records or in community surveys. Some studies

have found that undocumented immigrants have better health outcomes and positive health behaviors than the native-born (Dang et al., 2011; Kelaher and Jessop, 2002; Korinek and Smith, 2011; Reed et al., 2005). Other studies have found that undocumented immigrants had higher rates on some negative health outcomes (Landale et al., 2015a; Wallace et al., 2012). Despite these mixed results, there seems to be agreement that even if undocumented immigrants have better physical health status than the native-born, they may experience a faster decline of their mental health. Their undocumented status creates a social stigma, fear of discovery and deportation, and related stressors that have negative consequences for adults and their children (Gonzales et al., 2013; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2011; Sullivan and Rehm, 2005; Yoshikawa, 2011; also see Chapter 3).

International Comparisons

It is difficult to compare health indicators across countries because of different data collection methods and systems, differences in the measurement of health and immigrant status, and the frequency of data collection efforts. Despite these challenges, it is possible to make a broad assessment of this issue. The available evidence suggests that the immigrant pattern in the United States is not consistently found across different countries. Canada is similar to the United States, with Canadian immigrant men and women having a lower incidence of chronic conditions than Canadian-born men and women (McDonald and Kennedy, 2004). Canadian immigrants have lower rates of depression and alcohol dependence than the Canadian-born (Ali, 2002), although this pattern does not hold true for all immigrant populations (Islam, 2013). In Europe, the association between immigrant status and health is not as consistent (Domnich et al., 2012). One study examined the health of adults 50 years and older and found that immigrants were comparatively worse off on various dimensions of health than the native-born population across 11 European countries (Sole-Auro and Crimmins, 2008). Moullan and Jusot (2014) found that immigrants in France, Belgium, and Spain reported poorer health status than the native-born in their respective countries. Italian immigrants, on the other hand, reported better health than Italian native-born. Noymer and Lee (2013), in a study of immigrant status and self-rated health across 32 countries, found only two countries have poorer immigrant health than native-born (Macedonia and Switzerland), whereas three countries (Moldova, Nigeria, and Ukraine) have better immigrant health compared to the native-born in each country. The authors concluded that the age structure of immigrants compared to the native-born population may explain some of the variation found in health status between groups.

Possible Explanations for the Health Advantage among Immigrants

The terms “immigrant paradox” or “epidemiological paradox” are frequently used to refer to the pattern that immigrants tend to have better health outcomes than the native born. This paradox is especially pertinent for immigrants who come to the United States with low levels of education and income. Yet the sources of this paradox are not well understood, and are a subject of debate in the literature (Jasso et al., 2004; Markides and Rote, 2015). Below, the panel discusses some potentially relevant data sources that help account for this pattern of immigrant health.

Immigrants may endure difficulties and hardships as they grow accustomed to the social norms and lifestyles in the United States. They may encounter difficulties securing permanent residences in safe neighborhoods, earning decent wages for their work, finding resources for their social and health care needs, creating opportunities to expand their social networks, and sending their children to good schools. The transition may be made even more difficult if communities are not receptive to them. These difficulties may create conditions and stressors that are often associated with disease. Since low levels of education and income are strongly associated with poor health, immigrants with limited economic and social means are expected to be at even greater risk for health problems. But despite these elevated risks, even socioeconomically disadvantaged immigrants generally have better health outcomes than the general population of native-born.

Some immigrants arrive from countries that enjoy better health outcomes than the United States. Although the United States spends considerably more on medical technologies and clinical care than many other countries, these expenditures have not resulted in a healthier population. In 2011, for example, health care expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) were about 2.5 times higher than the average of all OECD countries and 50 percent higher than Switzerland and Norway, the next two highest health care spenders (OECD, 2013). Yet the United States has higher rates of cancer, HIV/AIDS, and obesity-related illnesses like diabetes and heart disease compared with other OECD member countries (OECD, 2013). And it has higher rates of disease and injury from birth to age 75 years for men and women and across ethnoracial groups than many other developed countries, including Canada and the United Kingdom (Woolf and Aron, 2013). These poorer health outcomes are evident even for people with high incomes, college educations, health insurance, and healthy lifestyles compared to their peers in other wealthy countries (Woolf and Aron, 2013). Thus, part of the explanation for the “paradox” may be that although immigrants may come to the United States for the perceived social and economic advantages relative to their home countries, better health is not necessarily one of them.

Two related explanations for any immigrant health advantage compared to native-born peers are the selection effect and the “salmon bias,” or return migration. The selection effect occurs when people who are healthier than residents of the sending country migrate to the United States more frequently than their fellow residents who are less healthy. For instance, Jasso and colleagues (2004) compared average life expectancy of immigrants and residents in sending countries. They found a substantial potential selection effect, with male immigrants to the United States having longer life expectancies than the general population of males born in the sending countries. Male Asian immigrant life expectancy in the United States, for example, may be as much as 10 years greater than the average for the male population in Asian sending countries. Among Hispanics, although immigrant males show a life expectancy advantage over native-born Hispanics, the difference is only about 5 years. Abraido-Lanza and colleagues (1999) take a different approach, comparing foreign-born Latino males and females with their foreign-born white counterparts. They find that Latino foreign-born have lower mortality rates than the white foreign-born, challenging the selection effect explanation for the immigrant health advantage. If a selection effect exists, it holds for Latinos and Asians, but not white immigrants.

It is difficult to test for a selection effect since most datasets on immigrants do not collect data on health of people before migration, but, some creative analyses of existing datasets provide insights about a possible selection effect. For example, Akresh and Frank (2008) analyzed data from the first round of the New Immigrant Survey 2003 Cohort to assess how health selectivity differs across regions of origin. Their analyses showed evidence of a health selection effect, based on comparisons of self-rated health, for all sending countries. Immigrants from all regions were more likely to experience positive health selection than negative selection, with western European and African immigrants having the highest proportion of positive selection and Mexican immigrants the lowest. But when socioeconomic controls were added to the analyses, the differences in positive health selection among different sending regions were substantially reduced. Selectivity is a complex process that may have differential effects on different health conditions and other social factors such as gender (Martinez and Aguayo-Tellez, 2014).

Return migration works in the opposite direction from the selection effect: sicker or less fit immigrants return to their home countries, leaving a healthier immigrant population in the United States. Immigrants, especially older adults, may return to access health care they are more familiar with, seek the support and care of family members and friends, or to die in their place of birth. For instance, Palloni and Arias (2004) found that older Mexican-born immigrants did return to Mexico when ill, and this return migration may affect the life expectancy rates of immigrants who

remained in the United States. Other researchers found a modest return bias (Turra and Elo, 2008; Riosmena et al., 2013). However, Abraido-Lanza and colleagues (1999) did not find evidence for a return bias in explaining the Latino mortality advantage.

Social and cultural factors constitute another set of explanations for the immigrant health advantage, particularly in explaining why their health status may worsen over time. Immigrants may come to the United States with behaviors and values that lead to healthy diets and lifestyles, but over time, they and their children learn U.S. norms and practices that may be less healthy in the long term, such as a diet of frequent fast foods, heavy alcohol and substance consumption, and less involvement in family life (Abraido-Lanza et al., 2005; Dubowitz et al., 2010). Immigrants coming at earlier ages, especially during childhood, have the longest risk period. With more years in the United States, diet and physical inactivity of immigrant youth approach those of the native-born (Gordon-Larsen et al., 2003). Immigrant children may also have a larger set of social groups and networks available to them than older immigrants and, as a result could experience a greater amount of negative stressors and influences that lead to detrimental health outcomes as they mature and become adults.

Smoking is a lifestyle factor that has a large effect on mortality rates. Immigrants in the UnitedStates have lower rates of smoking rates than the native-born of the same ethnicity or the general native-born population (Larisey et al., 2013; Shankar et al., 2000; Unger et al., 2000). New migrants to the United States also tend to have lower rates of smoking than do people in their countries of origin (Bosdriesz et al., 2013), but over time the risk of smoking increases as they stay in the United States (Singh et al., 2013). Some recent research attributes as much as 50 percent of the difference in life expectancy at 50 years between foreign- and native-born men and 70 percent of the difference between foreign- and native born women to lower smoking-related mortality (Blue and Fenelon, 2011; Cantu et al., 2013).

Worksite environments and the safety in workplaces may partially explain the worsening health status among immigrants over time. Immigrants who are poor or have low levels of skills may take jobs in neighborhoods with high levels of pollutants, near toxic dump sites, or with frayed water and sanitation infrastructure that are at risk for collapse when natural or manmade disasters occur (Pellow and Park, 2002). They may also work in hazardous jobs or in settings where harmful chemicals are present, such as in some agricultural occupations or in nail salons (Park and Pellow, 2011). While immigrants may not necessarily work in the most hazardous jobs compared to the native-born, they may not receive the best training and counseling to manage their safety and well-being in these workplace or neighborhoods (Hall and Greenman, 2014). The constant exposure to

physical harm and chemicals can take its toll on the body and on mental health, potentially leading to declining health.

Despite these promising and noteworthy findings, there is no single definitive explanation why immigrants generally have better health outcomes than the native-born when they first arrive, or why their health eventually declines over time and over generations. Past research on these topics tends to use different datasets, conceptual models, analytic samples, measures, and time periods. Most existing datasets that include large samples of immigrants do not include extensive information about health status and other social conditions prior to the migration experience. Moreover, existing datasets are unable to track immigrants to fully capture how health changes over time and what factors may contribute to these changes. There is evidence, however, that selection, return migration, and social and cultural factors contribute to some extent to the immigrant health advantage and the changes in health over time.

IMMIGRANT INTEGRATION AND HEALTH

Immigrants may have an initial health advantage when they first arrive in the United States, but this advantage tends to decrease when some dimensions of integration are considered. The research on these dimensions establishes an association with health but not necessarily the causal effects. Accordingly, it is possible that while a statistically significant association can be demonstrated between some dimensions of integration and health, other factors may actually be responsible for the effect. One common dimension of integration in health research is the time spent in the United States. Research has documented higher rates of different health problems including hypertension, chronic illness, smoking, diabetes, and heavy alcohol use as length of residency increases (Alegria et al., 2007a; Jackson et al., 2007; Moran et al., 2007; O’Brien et al., 2014; Ro, 2014; Singh et al., 2013; Takeuchi et al., 2007). Since length of residence is often correlated with integration across other dimensions, this research suggests that increased integration may have a negative effect on health. Yet despite this general finding, it is not possible to conclude that the length of residence in the United States shows a linear association with health problems because the studies vary in how length of residence is categorized (e.g., in 5-year, 10-year, or 20-year intervals), in the health outcome measured, and in the immigrant group under consideration (Ro, 2014; Zsembik and Fennell, 2005). More clearly defined research that allows results to be linked across studies on this topic is warranted. In addition, negative health outcomes may result from the challenges to integration, for example, the accumulated stress resulting from discrimination, poor working conditions, undocumented legal status, and limited English proficiency (Finch and Vega, 2003;

Yoo et al., 2009). Lack of access to health insurance and adequate health care may also play a role, as discussed below.

Another important integration measure is generational status, since the expectation is that second and subsequent generations will be more integrated into American society than their parents. While data on the health of the children of immigrants are somewhat scarce, the empirical literature suggests a pattern of declining health status after the immigrant generation, although the pattern may differ depending on the health outcome and the ethnic group (Marks et al., 2014). For example, second generation Hispanic and Asian adolescents have shown much higher rates of obesity than the first generation (Popkin and Udry, 1998; Singh et al., 2013). Children of recent immigrants have encountered weight problems across socioeconomic (SES) status, and this was especially so for sons of non-English speaking parents (Van Hook and Baker, 2010).

Three national studies of black, Asian, and Latino immigrant adults found some generational association with mental disorders. Second and third generation Caribbean blacks had higher rates of psychiatric disorders than the first generation; the third generation had substantively higher rates of psychiatric disorders (Williams et al., 2007). Third generation Latinos also had significant higher rates of psychiatric disorders than the first and second generations (Alegria et al., 2007a), and the generational pattern for Asian Americans was similar (Takeuchi et al., 2007). A decline in health status for the third generation was also found in surveys in which respondents self-reported on their health status (self-rated health). Data from the Current Population Survey showed that the third generation had higher odds of reporting poor/fair self-rated health than the first generation. This effect was particular strong for blacks and Hispanics, but not for Asians (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2010).

Higher levels of educational attainment have often been associated with increased cognitive functioning, better quality and higher paying jobs, more integration into civic life, and access to broader social networks, all of which can lead to better health (Mirowsky and Ross, 2003). In many respects, researchers consider education to be the causal mechanism (or a major causal factor) that leads to economic and social rewards and a better quality of life, and increases in educational attainment have also corresponded with incremental improvements in health status (Adler et al., 1994; Edgerter et al., 2011). Education has also been positively correlated with immigrant integration (see Chapter 6).

Despite this robust association, not all groups have shown the same positive associations between rewarding outcomes and education (see Conley, 1999; Farmer and Ferraro, 2005; Massey, 2008; National Research Council, 2001; Oliver and Shapiro, 1997). For example, the education and health association has been markedly weaker among Latino and Asian

immigrants than it has been for non-Hispanic whites (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2007; Goldman et al., 2006; Kimbro et al., 2008; Leu et al., 2008; Walton et al., 2009). The reason for this weaker association is not clearly established yet, but one possible reason is that where one receives the major part of her/his education experiences matters for social mobility and health. Immigrants may find that their educational achievements are undervalued in the United States, and they may not receive the same compensation and prestige for their educational accomplishments (Zeng and Xie, 2004). Education in another country, when compared to schooling in the United States, constrains economic opportunities, reduces positive social interactions, and limits English proficiency; these factors in turn are associated with less-positive health status (Walton et al., 2009). In addition, the educational gradient (i.e., positive correlations between educational attainment and other positive risk factors or outcomes) in the United States may be weaker or reversed in some sending countries. For example, people at higher SES levels in Latin America were shown to be more likely to eat higher calorie foods, smoke tobacco, and consume alcohol. These behaviors, while not conducive to better health, may have been associated with higher social status. Accordingly, immigrants may engage in these behaviors as they climb the educational and economic ladder (Buttenheim et al., 2010).

The ability to speak English in the United States is another often used measure of immigrant integration. Proficiency in English allows immigrants to communicate with people who do not speak their ethnic language and to manage their daily routines, whereas inability to speak English can limit opportunities for jobs and schooling, reduce abilities to expand networks and communicate with others, and constrain access to social and health services. Given its importance for social interactions in the United States, it is not surprising that English proficiency has been found to be strongly associated with health among Asian, black, and Latino immigrants (Gee et al. 2010; Kimbro et al., 2012; Okafor et al., 2013). Equally important, the ability to communicate in both English and one’s ethnic language has been strongly associated with positive health (Gee et al., 2010; Kimbro et al., 2012). Chen and colleagues (2008) found that bilingual proficiency provided access to resources in both immigrant and non-immigrant communities, creating more opportunities for social mobility.

Residency, generational status, education, and English-language proficiency are individual characteristics that have been associated with health. Measures of discrimination and ethnic density of residential neighborhoods capture facets of the societal receptivity and responses that influence the health of immigrants. Perceived discrimination is frequently considered a type of stressor that can cause wear and tear on the body and psyche and eventually lead to premature illness and death (Williams and Mohammed, 2009). Perceived discrimination has been associated with a wide range

of health behaviors and outcomes, such as smoking, alcohol use, obesity, hypertension, breast cancer, depression, anxiety, psychological distress, substance use, and self-rated health across ethnoracial groups (Gee et al., 2009; Pascoe and Smart, 2009; Williams and Mohammed, 2009). While fewer studies have focused specifically on immigrants, their findings support the general pattern that perceived discrimination is significantly associated with health outcomes (Gee et al., 2006; Ryan et al., 2006; Yoo et al., 2009). For example, Yoo and colleagues (2009) found that perceived language discrimination (the perception that a person is unfairly treated because of accent or English-speaking ability) had a strong association with health, particularly for Asian immigrants living in the United States for 10 years or more. The overall body of this research suggests that the perception that others are not receptive to one’s presence is strongly associated with health outcomes for different ethnic groups and immigrants.

Violence against women, including intimate partner violence, rape and sexual assault, and other forms of sexual violence, is a public health problem that has been associated with poor health of women including depression, suicidality, sexually transmitted diseases, and death. In the United States, immigrant women do not appear to experience higher rates of domestic violence than the native-born, but their social positions may exacerbate the consequences of these assaults (Menjívar and Salcido, 2002). Some women come to the United States already in a violent relationship (Salcido and Adelman, 2004), while others may encounter violence after immigration. Research has found that limited English proficiency, isolation from family and community members, uncertain legal status, lack of access to good and dignified jobs, and past experiences with authorities in the sending country and the United States are all factors that can prevent abused immigrant women from reporting the crime or from leaving the family situation (Erez, 2000; Menjívar and Salcido, 2002). Violence against women is a difficult topic to study because women and family members may not want to talk about it for these same reasons that constrain them from reporting it to authorities. However, because domestic violence has detrimental consequences for the health of immigrant women and their children, innovative methods and strategies to overcome research obstacles to assessing its occurrence and contributing factors will go a long way toward addressing this major public health challenge.

The past two decades have seen a renewed focus on how geographic locations or places influence health (Burton et al., 2011). “Place” refers to any geographically located aggregate of people, practices, and built/natural objects that is invested with meaning and value (Gieryn, 2000). In this sense, place is a social and ecological force with detectable and independent effects on social life and individual well-being (Habraken, 1998; Werlen, 1993). Places reflect and reinforce social advantages and disadvantages by

extending or denying opportunities, life-chances, and social networks to groups located in salutary or detrimental locales (Gieryn, 2000). Massey (2003), for example, showed that racial segregation produces a high allostatic load2 for African Americans that have dire consequences on well-being. An immigrant’s place has been shown to have negative attributes, such as high levels of poverty, limited jobs and services, extensive violence and crime, concentration of environmental hazards such as air pollution, and low levels of commitment and trust (Williams and Collins, 2001). Yet place can also be positive and protect residents from discrimination while offering high levels of social support, access to social and health services, ample parks and recreational activities, and accessible markets with fresh produce (Moreland et al., 2006; Sallis and Glanz, 2006; Walton, 2014).

Immigrants may live in places with a high proportion of people from the same ethnic backgrounds, especially when they first arrive, and this ethnic density is expected to be positive and supportive (Mair et al., 2010). Most studies have not found an effect between ethnic density and health, but when they have, positive effects were more common than negative ones (Bécares et al., 2012). A majority of these studies focus on the physical health of African Americans and Mexican Americans, and very few include immigrants in the samples. But a recent study provides additional insights: Lee and Liechty (2014) found that ethnic density was associated with lower depressive symptoms for Latino immigrant youth, but not for non-immigrant Latino adolescents. This study raises the possibility that the effects of ethnic density may depend on nativity, developmental stage, health outcomes, and the history of the group in the community (Osypuk, 2012). Longitudinal studies are needed for additional research on the places where immigrants reside and the relationships among place, health status and access to care, and integration.

ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE AMONG IMMIGRANTS

Unlike the overall health advantage, immigrants are at a distinct disadvantage compared to the native-born when it comes to receiving adequate and appropriate care to meet their preventive and medical health needs (Derose et al., 2007). This is a consistent and robust finding of research that covers physical and mental health problems among Asian, Black, and Latino immigrants (Abe-Kim et al., 2007; Alegria et al., 2007b; Jackson

___________________

2 Allostatic load is the cost, or “wear and tear,” to the human body of stress response to everyday life. Allostatic load reflects “not only the impact of life experiences but also of genetic load; individual habits reflecting items such as diet, exercise, and substance abuse; and developmental experiences that set lifelong patterns of behavior and physiological reactivity” (McEwen and Seeman, 1999, p. 30).

et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2013; Wafula and Snipes, 2014). This finding also extends to the research on undocumented immigrants, who were found to be less likely than native-born or other immigrants to have a usual source of care, visit a medical professional in an outpatient setting, use mental health services, or receive dental care (Derose et al., 2009; Pourat et al., 2014; Rodriguez et al., 2009). Per capita health care spending has been found to be lower for all immigrants, including the undocumented, than it was for the native-born (Derose et al., 2009; DuBard and Massing, 2007; Stimpson et al., 2010).

The lack of health insurance or inadequate insurance coverage are often cited as a primary source of constraint preventing immigrants from using health care services in a timely manner. Singh and colleagues (2013) found that immigrants have consistently lower rates of health insurance coverage than native-born populations at different age groupings and countries of origin. Immigrants 18 years and younger have four times the proportion of uninsured than do the native-born (29% to 7%); among 18-64-year-old immigrants, the prevalence of uninsured was 38 percent, compared to 18 percent among the native-born (Singh et al., 2013). In the age 65 and older category, they found that the prevalence of uninsured was lower for both groups and the difference was not as striking (5% to 3%). Immigrants born in Latin American countries were the most likely to be uninsured among both the group under 18 years of age (41%) and among 18-64-year-olds (52%). Immigrants from African and Latin American countries had the highest uninsured rates in the 65 years and older age group, with approximately 9 percent of that group being without insurance coverage (Singh et al., 2013). Wallace and colleagues (2012) found that the estimated percentage of undocumented immigrants (all regions of origin) without insurance was substantial, at about 61 percent.

Despite its importance, insurance coverage is the not the sole barrier to access to health care for immigrants (Clough et al., 2013; Derose et al., 2007; Ku, 2014; Perreira, et al., 2012). Hospitals, clinics, and community health centers may not have the appropriate staffing and capabilities to adequately communicate and serve some immigrant groups. Costs for health care—including medication—are high, and immigrants, especially those without health insurance coverage, may not have the capacity to pay these costs. Some immigrants may have to work at multiple jobs just to pay for their daily living expenses and are unable to find the time to seek care for their health problems (Chaufan et al., 2012). Many immigrants may not speak English or may not speak it well enough to negotiate access to needed health services (Flores, 2006; Timmins, 2002). Language can also limit knowledge about community services, create misunderstandings between patient and medical staff, and reduce effective communication between patient and physician (Cristancho et al., 2008). Public tensions around immigration may create a

stigma about immigrants and lead to biases against immigrants among health care providers and staff, causing immigrants to avoid health care in public settings (Cristancho et al., 2008; Derose et al., 2009; Lauderdale et al., 2006). In addition, the safety net for health care continues to shrink and public programs for immigrants may not be available especially in new destinations (Crowley and Lichter, 2009; Ku and Matani, 2001). Undocumented immigrants may avoid contact with medical personnel and settings because they fear they will be reported to authorities and eventually deported (Heyman et al., 2009). In addition, the complexities of health care and insurance in the United States may make it difficult even for those who have health insurance to access care (Ngo-Metzger et al., 2003).

These challenges to improving access to health care for immigrants have led to many innovative government and public programs at the national, local, and community levels. The most ambitious program is the ACA, which was passed in 2010 and is intended to help a large number of immigrants to access health insurance (see below). However, ACA is not expected to change the number of uninsured among undocumented immigrants (Zuckerman et al., 2011). While it is not possible in this report to document all the programs that address access to care among immigrants, Yoshikawa and colleagues (2014) provide insights about what successful community-based organizations (CBO) can do to increase access to quality care and to provide better care. Among their suggestions are the following: (1) take advantage of strong family and community networks within immigrant neighborhoods for outreach; (2) establish collaboration and regular communication between CBOs and government agencies; (3) coordinate multiple service providers in the same location; (4) train trusted community members to disseminate health information (e.g., through the promotores programs found in some Latino immigrant communities); (5) address barriers for unauthorized parents to enrolling their U.S.-citizen children; and (6) address immediate needs as an entry point to accessing broader services.

Immigrants and the Affordable Care Act3

The ACA seeks to expand health insurance coverage through Medicaid expansions, the creation of health insurance exchanges (marketplaces) coupled with federal tax subsidies, and a requirement that people have health insurance or pay a tax penalty.4 Embedded in both its policy development and implementation were a variety of exceptions concerning policies for

___________________

3 The following discussion of the Affordable Care Act is edited and condensed from a longer paper prepared for the panel (Ku, 2014).

4 For more details on the Affordable Care Act, including the full text of the law, see http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/rights/index.html [September 2015].

immigrants, particularly those who are undocumented. A fundamental goal of the ACA was to incrementally expand health insurance coverage, largely beginning in 2014.5 Since immigrants, particularly Latinos, are disproportionately uninsured, they were important targets of insurance expansion efforts, but other factors, discussed below, may be making it hard to reach immigrant communities effectively.

Three major components of the law were

- Medicaid Expansion for Adults. Prior to the ACA, most states did not provide Medicaid to adults without dependent children, no matter how poor. In addition, most states have established Medicaid or State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) income eligibility for children at or above 200% of the poverty line. The ACA was designed to expand Medicaid for nonelderly adults up to 138 percent of the poverty line, including parents and childless adults. However, in the summer of 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that states had the option whether to expand Medicaid or not (National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S.__, 132 S. Ct 2566).

- Health Insurance Exchanges and Federal Tax Credits. The ACA also established the development of health insurance exchanges (also called marketplaces), which are Internet-based marketplaces where individuals and small business can shop for health insurance. The marketplaces are divided into those for individuals and families and those for enrolling through small businesses (the Small Business Health Options Program or SHOP). Individuals who are not otherwise eligible for insurance (e.g., through an employer) and who purchase insurance through an exchange are eligible for federal tax credits if they have incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the poverty line. In states that expand Medicaid, the subsidy range is generally 138 percent to 400 percent of the poverty line. There are exchanges in all states, but only about one-third were established by state agencies. The others were established in whole or in part by the federal government because the state in question chose not to create an exchange.

- Individual Responsibility. The ACA also established a requirement that people must either have insurance or face a tax penalty, unless insurance is otherwise unaffordable. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of this requirement.

In all three areas, there are differences in policies for immigrants based

___________________

5 See http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts/timeline/timeline-text.html [September 2015].

on legal status. The ACA clearly states that the undocumented are not eligible for the health insurance exchanges nor for the federal tax credits that accompany them, and they remain ineligible for Medicaid. This applies even for those who receive a temporary reprieve from deportation and work authorization through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) provisions. Nonetheless, the ACA creates major opportunities to increase health insurance coverage for legal-status noncitizen immigrants. The ACA makes millions of “lawfully present” immigrants eligible for the health exchanges and the federal tax credits on the same terms as citizens, which could greatly expand access to private insurance coverage (Ku, 2013). The “lawfully present” standard is broader than the prior legal standards established for Medicaid eligibility. All lawful permanent residents, including those who have been in the United States for less than 5 years, are “lawfully present” under the ACA and are eligible for exchanges and tax credits. In addition, many lawful noncitizens who lack LPR status are also lawfully present and eligible for the exchanges and tax credits, although there is a length-of-residency requirement (see Table 3-2 in Chapter 3). Lawfully present immigrants with incomes under 100 percent or 138 percent of poverty who are otherwise ineligible for Medicaid are also eligible for health exchanges and federal tax credits. Data from the Department of Homeland Security indicate that in 2011 there were about 4 million LPRs who were residents for under 5 years and 1.9 million “nonimmigrant” residents, such as those with work visas (Rytina, 2013). Thus, a conservative estimate is that as many as 6 million noncitizen immigrants may have gained eligibility for private health insurance coverage through health insurance exchanges under the ACA.

Preliminary Effects of the ACA on Immigrants’ Insurance Coverage

Since the ACA insurance expansions only began in January 2014, it is likely that the full impact of this law will not be known for many years, as implementation continues and as evidence accumulates. Analysts, including the Congressional Budget Office,6 generally expect enrollment in the health insurance exchanges and Medicaid to continue to gradually increase, as familiarity with the programs grows and administrative and political kinks are ironed out (Holohan, 2012). Nonetheless, some evidence has begun to accumulate about preliminary insurance enrollment and the effects on health insurance coverage. The key evidence falls into two categories: administrative reports and early household surveys. Both forms of evidence indicate that millions of people enrolled in health insurance exchanges and

___________________

6 For Congressional Budget Office Baseline Projections, see https://www.cbo.gov/publication/43900 [September 2015].

that Medicaid enrollment has increased, particularly in states that expanded Medicaid eligibility (Blumenthal and Collins, 2014; Sommers et al., 2013, 2014a). Early household surveys have revealed that the percentage of the population that is uninsured has declined significantly between 2013 and 2014 (Blumenthal and Collins, 2014).

None of the early published reports document the extent to which immigrants have enrolled or gained insurance coverage (aside from press releases about documentation of citizenship status, discussed below). Some inferences may be drawn based on data about enrollment or insurance coverage of Latinos or Asian Americans, since the majority of U.S. immigrants are Latino or Asian. But inferences about immigration status are inherently imperfect because of the lack of actual data on immigrant or citizenship status. Substantial shares of the Latino and Asian immigrants (first generation) in the United States are either naturalized citizens or have lawful status. In general, these studies have found that, while health reform has led to substantial improvements in overall health insurance coverage, including gains for Latinos (Doty et al., 2014) and Asians (Ramakrishnan and Ahmad, 2014), there is some evidence that improvements for Latinos have lagged behind those of other groups (Doty et al., 2014; Ortega et al., 2015).

Administrative data indicate that between October 2013 and March 2014 over 8 million people enrolled (selected a health plan) in health insurance exchanges. A federal report provided racial/ethnic statistics for the 5.4 million who were enrolled in health insurance programs through the federally facilitated exchanges: 7.4 percent were Latino and 5.5 percent were Asian, but 31 percent of people did not report race/ethnicity (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2013). By comparison, Ku (2014) found that Latinos constituted 17 percent of the U.S. population and 32 percent of the uninsured, while Asians were 5 percent of the population and 5 percent of the uninsured population. Thus, Latinos appear to be underrepresented in the federally facilitated exchanges, whereas Asian enrollment through these exchanges appears to be roughly in proportion to the overall population. Ku (2014) also reported that in California, a state-based exchange with the largest program in the nation, of the 1.0 million who enrolled by March 2014, 28 percent of exchange enrollees were Latino and 21 percent were Asian (4% did not report race/ ethnicity). For California, Ku found that 38 percent of the population and 57 percent of the uninsured are Latino, while 14 percent of the population and 12 percent of the uninsured are Asian. Latinos in California therefore appear underrepresented in that state’s enrollment through its exchange, while Asians appear somewhat overrepresented.

Medicaid administrative data show that Medicaid enrollment grew by 7.7 million (or 12.4%) from July-September 2013 to June 2014. The growth was much larger—6.3 million new enrollees or 18.5 percent—in

the 26 states (and the District of Columbia) expanding Medicaid under the provisions of the ACA than in the 24 states that chose not expand Medicaid (approximately 1 million new enrollees total, or 4.0% growth rate) (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2014). Data about changes in enrollment by race/ethnicity or immigration status are not yet available from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. Since a large proportion of uninsured people are in low-income households, it is plausible to expect higher minority participation as a result of Medicaid expansions (and publicity about health reform in general), but the relevant Medicaid administrative data to investigate this expectation are not yet available.

Household surveys, based on self-reported insurance status, are another way to gain insights about changes in insurance coverage. Typically, these data are reported on an annual basis after a survey-year has ended. For example, Census Bureau data for 2014 insurance status will probably be available in August or September 2015. But the nationwide interest in health reform has prompted the release of early findings based on the first few months of 2014.7

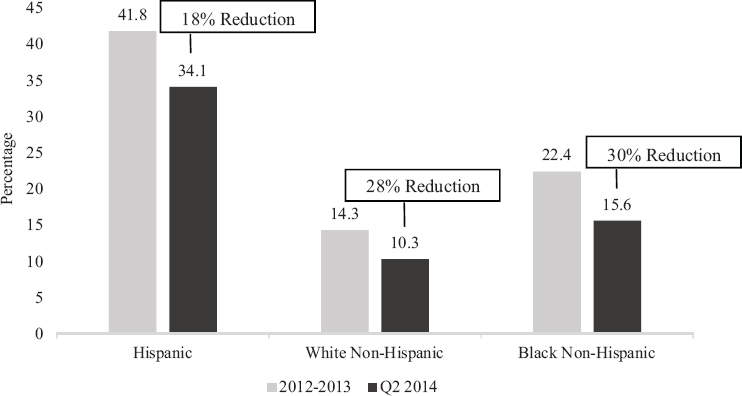

The largest of these early reports national daily poll on health issues, the Gallup-Healthways Well-being Index survey of households found that, among adults 18-64, the percentage uninsured fell from 21 percent in September 2013 to 16.3 percent in April of 2014, a decline of to 5.2 percent (Sommers et al, 2014b). Among Latinos, the percent uninsured fell by from 41.8 percent 2012 to 34.1 percent in 2014, an 18 percent reduction in the Hispanic insurance rate, see Figure 9-2). Among white non-Hispanics there was a 28 percent reduction in the uninsured rate, and a 30 percent reduction in the black non-Hispanic uninsured rate (Figure 9-2). Although the overall percentage point reduction was larger for Hispanics than for non-Hispanic white or black populations, the relative reduction in the uninsured was therefore smaller for Latinos The report on the early-month data from the survey also found that the reduction in the percent uninsured was much greater in states that expanded Medicaid in accordance with the ACA than in those states that chose not to expand.

The Urban Institute’s Health Reform Monitoring Surveys provide a slightly different perspective from the Gallup-Healthways Well-being Index survey. Shartzer et al. (2014) compared characteristics of adults 18-64 who were uninsured in September 2013 with those who remained uninsured in June 2014. When the authors compared the uninsured by Hispanic ethnicity, the found that among all adults who were uninsured, the proportion who were Hispanic grew from 33 percent in 2013 to 37 percent in 2014. Similarly, the share of the uninsured who were primarily Spanish-speaking

___________________

7 See http://kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/data-note-measuring-aca-early-impact-throughnational-polls/ [November 2015].

SOURCE: Data from Sommers et al. (2014). Original content from Ku (2014).

rose from 17 percent to 20 percent. Overall, self-identified Hispanic and Spanish-speaking adults had fewer improvements in insurance status than other ethnoracial groups. Since Spanish-speaking adults are particularly likely to be immigrants, this also indicates that insurance gains for Latinos lagged behind those of other groups.

Two other early reports have different results, however. The Commonwealth Fund’s Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey8 found larger reductions in the share of Latino adults who were uninsured than for white or black adults: the percentage of uninsured Latinos fell from 36 percent to 23 percent between July-September 2013 and April-June 2014, while the percentage of uninsured among white adults decreased from 16 percent to 12 percent and the percentage uninsured among blacks only decreased from 21 percent to 20 percent (Collins et al., 2014). Overall changes in the proportion of adults who were uninsured and the differences between Medicaid-expanding and non-expanding states in this survey were relatively

___________________

8 The Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey examined the effect if ACA’s open enrollment by interviewing nationally representative samples of 19-to-64-year-old adults at various points in time before and after open enrollment began. The April-June 2014 survey was conducted after the end of the second enrollment period and included a sample of adults who either had ACA marketplace or Medicaid coverage or might be eligible for that coverage. For further information on the methodology, see http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issuebriefs/2015/jun/experiences-marketplace-and-medicaid [November 2015].

similar to the results reported above from other surveys, so it is not clear why there is a discrepancy in the race/ethnicity results.

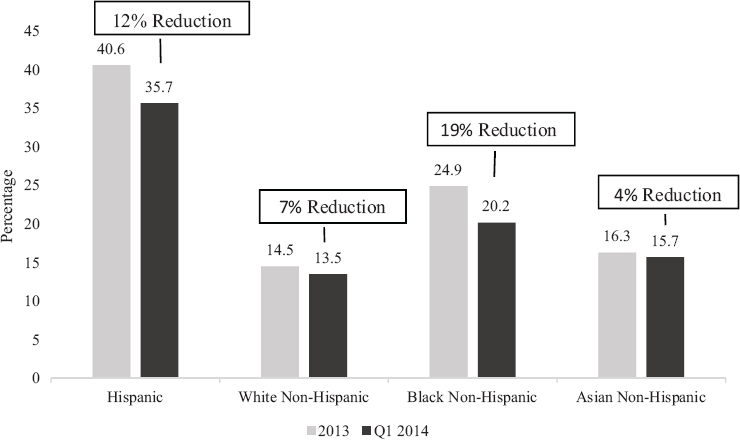

Early results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) also show a somewhat larger expansion in insurance coverage for Latinos than whites or Asians, though less than for black adults (Figure 9-3) (Cohen and Martinez, 2014). As illustrated in Figure 9-3, the relative share of uninsured Latinos fell by 12 percent between 2013 and the first quarter of 2014, compared to a 7 percent reduction for white non-Hispanics, 19 percent for black non-Hispanics, and 4 percent for Asians. The NHIS data also suggest that the gains in insurance coverage for Latinos were related to increases in both public and private insurance coverage. Like the other surveys, the NHIS data indicate there were changes in the overall insurance coverage of adults and larger gains in Medicaid expansion states than states not currently expanding. The discrepancy in results across the surveys with respect to health insurance coverage of Latinos is puzzling and indicates that we will need to wait for more detailed analyses and longer survey periods to get clear insights into differences in insurance status changes by race or ethnicity or changes by immigrant status.

SOURCE: Data from Cohen and Martinez (2014). Original content from Ku (2014).

Implementation Challenges

Initiating new programs can be challenging, and there is no question that the implementation of the ACA has been rocky. There were specific challenges that may have deterred participation by immigrants, most notably Latino immigrants, particularly at the beginning. First, eligibility and application policies and procedures about the new health insurance exchanges were complicated, and the rules about immigrant eligibility were especially complex. These rules were poorly understood not only by the public but even by public-sector and nonprofit-sector workers providing guidance on eligibility (Raymond-Flesch, 2015). Second, immigrants, especially those with limited English proficiency, had limited experience with the use of public benefits, including the concept of insurance; often live in immigrant enclaves, and may be socially isolated from other sources of information about public benefits (Perreira et al., 2012), even though the Navigator Program did attempt to address these challenges.9 Third, as noted by Weissberg (2014), the websites designed to facilitate enrollment in the health insurance marketplaces and Medicaid were generally English-only, particularly at the beginning. Although the federal government eventually released a Spanish version of its healthcare.gov website, it was criticized for faulty translations and difficulty of use.

Another potential challenge has been the citizenship verification process (Perreira et al., 2012). Because the undocumented are prohibited by law from participating in the ACA exchanges, everyone who has who applied for insurance coverage via the exchanges has had to verify their citizenship/ immigration status. A similar requirement already existed for Medicaid enrollment. If the data match process in the online system could not confirm that a person was a citizen or lawfully present immigrant, additional documentation was requested from the exchange user, even though that user may have entered the exchange on a provisional basis. However, the federal databases of citizens and lawfully present noncitizens are neither fully accurate nor up to date, and as of this report’s publication, many states continued to experience challenges with citizenship verification (Weiss and Sheedy, 2015).

Finally, there are variations in access by state: California, Massachusetts, and New York, for example, allow people with DACA status to receive Medicaid services under that state’s expansion of Medicaid. Most states do not have this policy. Given these challenges and the gradual mitigation of some of them over time, it will be important to continuing monitoring the response to ACA and its long-term effects in reducing the number

___________________

9 See http://icirr.org/content/immigrant-communities-face-major-barriers-navigating-affordable-care-act [November 2015].

of uninsured and increasing access to health care for immigrant adults and children (both citizens and lawfully present noncitizens), including patterns of state variation in the insurance coverage and the relationships between those patterns and states’ policies.

Although the ACA includes provisions that can help improve insurance coverage for millions of eligible immigrants, it is not clear how effective these policies have been in reaching this target population. This is partly due to the fact that the inevitable confusion that plagues initiation of any major policy made it harder to reach target populations in the first year of ACA implementation. In addition, a number of special barriers are likely to continue for immigrants, barriers that make it harder for them to be aware of or to apply for health insurance, even if they are uninsured and eligible under the law in its final form. These include language barriers, cultural misunderstanding, and fears about how a request for public benefits for which they may be eligible could jeopardize their immigration status. A combination of administrative remedies, such as better training of staff, bilingual or multilingual websites, enrollment information in multiple languages, and the availability of sufficiently knowledgeable and welcoming outreach and enrollment staff to help explain the new systems could reduce these barriers over time. Many of these remedies could be accomplished through the Navigator Program.

Immigrants’ integration into American society tends to produce mixed results when health issues are considered. In general, immigrants tend to have a better health profile than the native-born, but there is evidence of a decline over time on a variety of health indicators. The flip side of this condition is that immigrants are more likely to access health insurance and health care, the more integrated they are into American society. Early data indicate that the ACA will help provide health insurance to immigrants who had not been previously covered, with the exception of undocumented immigrants. This may improve health outcomes for immigrants and their descendants, although any improvement will be conditioned on legal status. Finally, while health insurance is important, an insurance card by itself does not, in the United States at least, guarantee access to good quality health care.

TWO-WAY EXCHANGE

Integration involves a reciprocal relationship between immigrants and society. Immigrants make an indelible impact on public health in the United States, and three areas are especially noteworthy in this regard. First, immigrants contribute to the health of the U.S. population. For instance, Preston and Elo (2014) found that, from 1990 to 2010, life expectancy in New York City rose by 6.25 years for females and 10.49 years for males.

The gains for the rest of the United States were much smaller by comparison: 2.39 years for females and 4.49 years for males. The authors concluded that the influx of immigrants into New York City contributed substantially to this increase in longevity.

Given that immigrants have a health advantage when they first arrive, their higher life expectancy also offer clues about cultural practices that lead to healthy lifestyles. Satia (2009) noted that traditional diets that include organic fresh fruits and vegetables, fewer fatty foods, and lower reliance on fast foods and sugary drinks are associated with lower rates of obesity, cancers, hypertension, and heart disease. Immigrants have also brought with them different forms of stress relief and healing that have become relatively common in American life and in some health care practices, including acupuncture, yoga, tai-chi, meditation, and mindfulness.

At a global level, immigrants contribute to the health care workforce, but the extent of the contribution, measured in numbers of immigrants in the care provider population, varies by country. The United States falls in the middle of the global range for proportion of immigrants among nurses and, among OECD countries, at the higher end of the range for immigrants among physicians (OECD, 2007). These immigrants fill a pressing need because of the shortage of health care personnel in the United States (Schumacher, 2010). Foreign-born physicians, for example, fill a critical need for primary care physicians in rural and underserved areas (Hart et al, 2007). In 2010, about 11.1 million people in the United States were employed in health care occupations and 1.8 million or 16 percent were foreign-born. Immigrants were disproportionately represented among both lower skilled nursing aids and doctors (Singer, 2012). The foreign-born were 16 percent of registered nurses and 27 percent of the physicians and surgeons. Among the immigrant health care workforce, 75 percent were women and 40 percent came from Asian countries (McCabe, 2012). About a third of all registered nurses come from the Philippines (Schumacher, 2011). In 2010, approximately 66 percent of all immigrants in the U.S. health care workforce were naturalized citizens, including 70 percent of physicians and 72 percent of registered nurses. It is expected that immigrants will continue to make contributions to the health care workforce in the future, especially in long-term care (Lowell, 2013; McCabe, 2012). Long-term care, which allows people to live independently as possible when they can no longer perform everyday activities on their own, will increase in importance as the proportion of older adults in the United States increases (Institute of Medicine, 2008).

A frequently overlooked health contribution of immigrants is their support of Medicare. Medicare is the federal health insurance program for people 65 years and older, for certain younger people with long-term disabilities, and for people who have permanent kidney failure requiring

dialysis or a transplant. More than 50 million Americans rely on Medicare as their primary health coverage. Zallman (2014) found that immigrants contribute more to Medicare than they receive in benefits. From 1996 to 2011, the contribution immigrants made to the Medical Hospital Insurance Trust Fund exceeded the benefits they received by $182.4 billion. By comparison, the native-born population produced an overall deficit in this part of Medicare of $68.7 billion over the same period. Without the contributions of immigrants to Medicare, the trust fund would be expected to become insolvent by the end of 2027 or 3 years earlier than currently estimated by the Medicare Trustees (Zallman, 2014).

Immigrants’ positive impact on health care expenditures and the health care system may extend beyond Medicare. For instance, per capita health care expenditures for immigrants are 55% lower than expenditures for the native-born (Mohanty et al., 2005), and insured immigrants have much lower medical expenses than insured native-born, implying that immigrants’ premiums may help subsidize insurance rates for the native-born (Ku, 2009). The taxes immigrants pay also contribute to funding for Medicaid, Title X for family planning, local health departments, and community clinics that serve both immigrants and the native-born.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Across various measures, immigrants in the United States are healthier than the native-born. The foreign-born show better infant, child, and adult health outcomes than the U.S.-born population in general and better outcomes than U.S.-born members of their ethnic group. In comparison with native-born Americans, the foreign born are less likely to die from cardiovascular disease and all cancers combined; they experience fewer chronic health conditions, lower infant mortality rates, lower rates of obesity, fewer functional limitations, and fewer learning disabilities. Immigrants also have a lower prevalence of depression, the most common mental disorder in the world, and of alcohol abuse. Foreign-born immigrants also live longer: they have a life expectancy of 80.0 years, 3.4 years higher than the native-born population. Across the major ethnic categories (non-Hispanic whites, blacks, Asian/Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics), immigrants have a life expectancy advantage over their native-born counterparts. However, these advantages diminish over time.

Conclusion 9-1 As length of residence and generational status increase, health advantages decline as their health status converges with the native-born. Further research should be done to identify the causal links between integration and health outcomes.

Conclusion 9-2 Immigrants are disadvantaged when it comes to receiving health care to meet their preventive and medical health needs. The ACA should improve this situation for lawfully present immigrants and naturalized citizens, but the undocumented are specifically excluded from all coverage under the ACA. In addition, the undocumented are not entitled to any nonemergency care in U.S. hospitals. Legal status therefore restricts access to health care, which may have detrimental effects for all immigrants’ health.

Although past empirical studies have built a solid foundation for understanding the health status and access to health care among immigrants, most of this work has used cross-sectional studies that make it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the causal mechanisms for the demonstrated associations, how immigrants become integrated into U.S. society and its health care systems, and the factors that affect the pace at which this integration occurs. Equally important, it is difficult to determine what specific changes in norms, values, and lifestyles are associated with changes in health status and the use of health care, and what the impact of the policy climate is on health outcomes. Longitudinal studies, such as the New Immigrant Survey (http://nis.princeton.edu/project.html [November 2015]), that can track immigrants over time provide critical scientific and policy insights about immigrant integration and health outcomes (see Chapter 10).

REFERENCES

Abe-Kim, J., Takeuchi, D.T., Hong, S., Zane, N., Sue, S., Spencer, M.S., Appel, H., Nicdao, E., and Alegria, M. (2007). Use of mental health–related services among immigrant and native-born Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 91-98.

Abraido-Lanza, A.F., Dohrenwend, B.P., Ng-Mak, D.S., and Turner, J.B. (1999). The Latino mortality paradox: A test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypothesis. American Journal of Public Health, 89(10), 1543-1548.

Abraido-Lanza, A.F., Chao, M.T., and Flores, K.R. (2005). Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Social Science and Medicine, 71, 1243-1255.

Acevedo-Garcia, D., Mah-J. Soobader, M-J., and Berkman, L.F. (2007). Low birthweight among U.S. Hispanic/Latino subgroups: The effect of maternal foreign-born status and education. Social Science and Medicine, 65, 2503-2517.

Acevedo-Garcia, D., Bates, L.M., and Osypuk, T.L. (2010). The effect of immigrant generation and duration on self-rated health among U.S. adults 2003-2007. Social Science and Medicine, 71(6), 1161-1172.

Adler, N.E., Boyce, T., Cheshey, M.A., Cohen, S., Folkman, S., Kahn, R.L., and Syme, L.S. (1994). Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist, 49, 15-24.

Aguirre, B.E., and Saenz, R. (2002). Testing the effects of collectively expected durations of migration: The naturalization of Mexicans and Cubans. International Migration Review, 36, 103-124.

Akresh, I.R., and Frank, R. (2008). Health selection among new immigrants. American Journal of Public Health, 98(1), 2058-2064.

Alegria, M., Mulvaney-Day N., Torres, M., Polo, A., Cao, Z., and Canino, G. (2007a). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 68-75.

Alegria, M., Mulvaney-Day, N., Woo, M., Torres, M., Gao, S., and Oddo, V. (2007b). Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 76-83.

Ali, J. (2002). Mental Health of Canada’s Immigrants. Supplement to Health Reports, Volume 13. Ottawa: Health Statistics Division, Statistics Canada. Available: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-003-s/2002001/pdf/82-003-s2002006-eng.pdf [October 2015].

Barcellos, S.H., Goldman, D.P., and Smith, J.P. (2012). Undiagnosed disease, especially diabetes, cast doubt on some of the reported health “advantage” of recent Mexican immigrants. Health Affairs, 31(12), 2727-2737.

Bécares, L., Shaw, R., Nazroo, J., Stafford, M., Albor, C., Atkin, K., Kierman, K., Wilkinson, R., and Pickett, K. (2012). Ethnic density effects on physical morbidity, mortality, and health behaviors: A systematic review of the literature. American Journal of Public Health, 102(12), e33-e66.

Birman, D., Beehler, S., Harris, E.M., Everson, M.L., Batia, K., Liautaud, J., Frazier, S., Atkins, M., Blanton, S., Buwalda, J., Fogg, L., and Cappella, E. (2008). International Family, Adult, and Child Enhancement Services (FACES): A community-based comprehensive services model for refugee children in resettlement. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(1), 121-132.

Bloemraad, R. (2000). Citizenship and immigration: a current review. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 1, 9-37.

Blue, L., and Fenelon, A. (2011). Explaining low mortality among U.S. immigrants relative to native-born Americans: The role of smoking. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(3), 786-793.

Blumenthal, D., and Collins, S.R. (2014). Health care coverage under the Affordable Care Act—A progress report. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(3), 275-281.

Bosdriesz, J.R., Lichthart, N., Witvliet, W.B., Busschers, K.S. Stronks, K. and Kunst, A.E. (2013) Smoking prevalence among migrants in the U.S. compared to the native born and the population in countries of origin. PLoS ONE, 8(3), e58654.

Brown, J.M., Council, C.L., Penne, M.A., and Gfroerer, J.C. (2005). Immigrants and Substance Use: Findings from the 1999-2001 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. DHHS Publication No. SMA 04-3909, Analytic Series A-23. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Burton, L.M., Kemp, S., Leung, M., Matthews, S.A. and Takeuchi, D. (2011). (Eds.). (2011). Communities, Neighborhoods, and Health: Expanding the Boundaries of Place. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Buttenheim, A., Goldman, N., Pebley, A.R., Wong, R. and Chung, C. (2010). Do Mexican immigrants “import” social gradients in health to the U.S.? Social Science & Medicine, 7, 1268-1276.

Cantu, P.A., Hayward, M.D., Hummer, R.A., and Chiu, C-T. (2013). New estimates of racial/ ethnic differences in life expectancy with chronic morbidity and functional loss: Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 28, 283-297.

Carswell, K., Blackburn, P., and Barker, C. (2011). The relationship between trauma, post-migration problems and the psychological well-being of refugee and asylum seekers. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57, 1007.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Obesity: Halting the Epidemic by Making Health Easier. Atlanta, GA: Author.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014). Medicaid and CHIP: June 2014 Monthly Applications Eligibility Determinations and Enrollment Report. Washington, DC: Author.

Chaufan, C., Constantino, S., and Davis, M. (2012). “It’s a full time job being poor”: Understanding barriers to diabetes prevention in immigrant communities in the USA. Critical Public Health, 22(2), 147-158.

Chen, S.X., Benet-Martinez, V., and Bond, M.H. (2008). Bicultural identity, bilingualism, and psychological adjustment in multicultural societies: Immigration-based and globalization-based acculturation. Journal of Personality, 76(4), 803-838.

Clough, J., Lee, S., and Chae, D.H. (2013). Barriers to health care among Asian immigrants in the United States: A traditional view. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 24(1), 384-403.

Cohen, R., and Martinez, M. (2014). Health Insurance Coverage: Early Reports of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January-March 2014. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Collins, S., Rasmussen, P., and Doty, M. (2014). Gaining Ground: Americans’ Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care after the Affordable Care Act’s First Open Enrollment Period. New York: Commonwealth Fund.

Conley, D. (1999). Being Black, Being in the Red: Race, Wealth and Social Policy in America. Oakland: University of California Press.

Cristancho, S., Garces, D.M., Peters, K.E., and Mueller, B.C. (2008). Listening to rural Hispanic immigrants in the Midwest: A community-based participatory assessment of major barriers to health care access and use. Qualitative Health Research, 18(5), 633-646.

Crowley, M., and Lichter, D.T. (2009). Social disorganization in new Latino destinations. Rural Sociology, 74(4), 573-604.

Dang, B.N., Van Dessel, L., Hanke, J., and Hilliard, M.A. (2011). Birth outcomes among low-income women—documented and undocumented. The Permanente Journal, 15(2), 39-43.

Derose, K.P., Escarce, J.J., and Lurie, N. (2007). Immigrants and health care: Sources of vulnerability. Health Affairs, 26(5), 1258-1268.

Derose, K.P., Bahne, B.W., Lurie, N. and Escarce, J.J. (2009). Review: Immigrants and health care access, quality and costs. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(4), 355-408.

Domnich, A., Panatto, D., Gasparini, R. and Amicizia, D. (2012). The “healthy immigrant” effect: Does it exist in Europe today? Italian Journal of Public Health, 9(3), 1-7.

Doty, M.M., Blumenthal, D., and Collins, S.R. (2014). The Affordable Care Act and health insurance for Latinos. Journal of the American Medical Association, 312(17), 1735-1736.

DuBard, C.A., and Massing, M.W. (2007). Trends in emergency Medicaid expenditures for recent and undocumented immigrants. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(10), 1085-1092.

Dubowitz, T., Bates, L.M., and Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2010). The Latino health paradox: Looking at the intersection of sociology and health. In C.E. Bird, P. Conrad, A.M. Fremont, and S. Timmermans (Eds.), Handbook of Medical Sociology (pp. 106-123). Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Edgerter, S., Braverman, P., Sadegh-Nobari, T., Grossman-Kahn, R., and Dekker, M. (2011). Education and Health: Exploring the Social Determinants of Health. Issue Brief #5. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Erez, E. (2000). Immigration, culture conflict and domestic violence/woman battering. Crime Prevention and Community Safety: An International Journal, 2(1), 27-36.

Farmer, M.M., and Ferraro, K. F. (2005). Are racial disparities in health conditional on socioeconomic status? Social Science & Medicine, 60, 191-204.

Finch, B.K., and Vega, W.A. (2003). Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health, 5(3),109-117.

Flores, G. (2006). Language barriers to health care in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(3), 229-231.

Garb, M. (2003). Health, morality, and housing: The “tenement problem” in Chicago. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1420-1430.