7

Sociocultural Dimensions of Immigrant Integration

In this chapter, the panel reviews research bearing on some key questions about the social and cultural dimensions of immigration. In doing so, we consider issues that often arouse popular fears and concerns, just as they did in earlier historical eras when massive numbers of new arrivals, the vast majority from Europe, were settling in this country. Today, as in the past, some worry that immigrants and their children do not share the same social values as the native-born, that they will not learn English and the dominance of English in the United States is under threat, and that immigrants are increasing crime rates. Some Americans experience discomfort about the introduction of new and unfamiliar religions. These fears generally are concentrated among a minority of Americans, but they often drive public discourse about immigration (see Chapter 1).

Since 2004, the Pew Research Center has conducted surveys that asked whether respondents believe that a “Growing number of newcomers from other countries strengthens American society, or threatens traditional American customs and values.” Although the results for responses to this question vary over time, the belief that immigrants threaten traditional American values and customs has generally been a minority opinion, averaging about 43 percent in 2013, while the proportion who believed that immigrants strengthen American society was 52 percent.1 There are significant differences in opinion by age, education, and partisanship (with older respondents, those without high school degrees, and Republicans more likely

___________________

1 See http://www.people-press.org/files/legacy-pdf/3-28-13%20Immigration%20Release.pdf [November 2015].

than others to say that immigrants threaten traditional American values and customs). Those Americans who do worry about immigration’s effect on American society are most concerned about Latinos and the Spanish language in particular (Brader et al, 2008; Hartman et al., 2014; Valentino et al., 2013; Hopkins et al., 2014).

In the sections below, the panel addresses these concerns by examining integration across several different sociocultural dimensions: public attitudes, language, religion, and crime. As the data and literature reviewed below suggest, today’s immigrants and their descendants do not appear to be very different from earlier waves of immigrants in their overall pace of integration. However, there are differences—both between historical and current immigrant groups and in the context in which they are integrating—that present new challenges for integration.

PUBLIC ATTITUDES

One measure of the extent to which immigrants and their descendants are becoming culturally integrated into the United States is the extent to which their attitudes about political and social issues converge with higher-generation native-born (Branton, 2007; de la Garza et al., 1996; Fraga, 2012; Fuchs, 1990; Hajnal and Lee, 2011). Data on attitudes on policy issues among immigrants and the native born are available from various sources. Most notably, the General Social Surveys from 1977 to 2014 asked questions about political ideology and opinions on key issues, including the role of the federal government, same-sex marriage, and access to the American Dream.2 The 2005-2006 Latino National Survey and the 2008 National Asian American Survey also contain sizable samples of immigrants to provide comparisons of attitudes by nativity for various national-origin groups. Overall, these data show that immigrants tend to support more government services, have weaker party identification, and are less likely to support same-sex marriage than the native-born. At the same time, there is significant convergence in attitudes between the native-born and foreign-born as individual immigrants spend longer time in the United States (Fraga et al., 2012; Lien et al., 2001; Wong, 2000; Wong et al., 2011).

Political Ideology and Party Identification

Two topics that have received close scrutiny because of their impact on the U.S. political system are the political ideologies and political partisanship of immigrants and their descendants (e.g., Alvarez and Bedolla, 2003;

___________________

2 See NORC’s General Social Survey website for variables and wording of questions at http://www3.norc.org/GSS+Website/Browse+GSS+Variables/Subject+Index/ [November 2015].

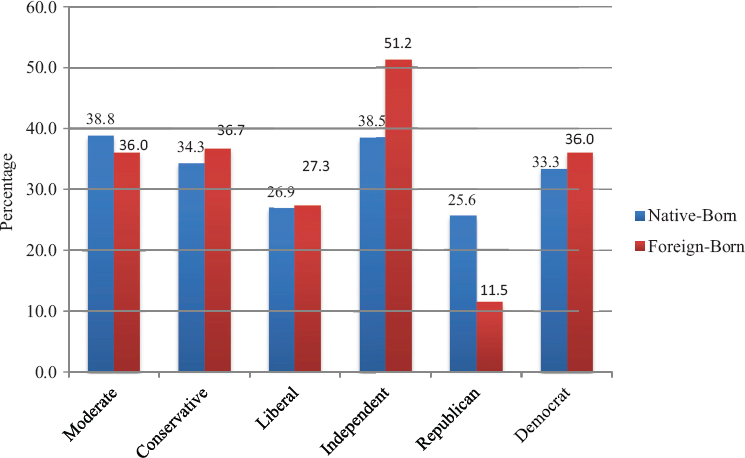

SOURCE: Data from General Social Survey.

Wong et al., 2011). The evidence suggests that immigrants are converging with the native-born in terms of political ideology, although immigrants tend to be less committed to one political party than the native-born (see Figure 7-1). In 2014, the largest percentage of both the foreign-born (44%) and native-born (39%) consider their political views to be moderate, while 38 percent of the native-born and 31 percent the foreign-born judge their views to be conservative. Approximately one-quarter of both groups state they hold liberal views. The political ideology of foreign-born respondents show more variation over time in comparison to the native-born, but the basic distribution across the three categories of political views (liberal, moderate, and conservative) is largely the same.

Yet when it comes to political parties, immigrants are much more likely to describe themselves as “independent” than the native-born, a finding that is borne out in surveys of both Latinos and Asian Americans (Figure 7-1). Unlike native-born citizens, immigrants did not grow up in households where they learned about U.S. politics from their parents, leaving them with weaker attachments to political parties. At the same time, immigrants tend to develop stronger party identification as they spend more years in the United States (Wong et al., 2011), although this depends to some extent on outreach by political parties and the extent to which they differentiate themselves on issues that immigrants care about (Wong, 2000; 2006; Hajnal and Lee, 2011).

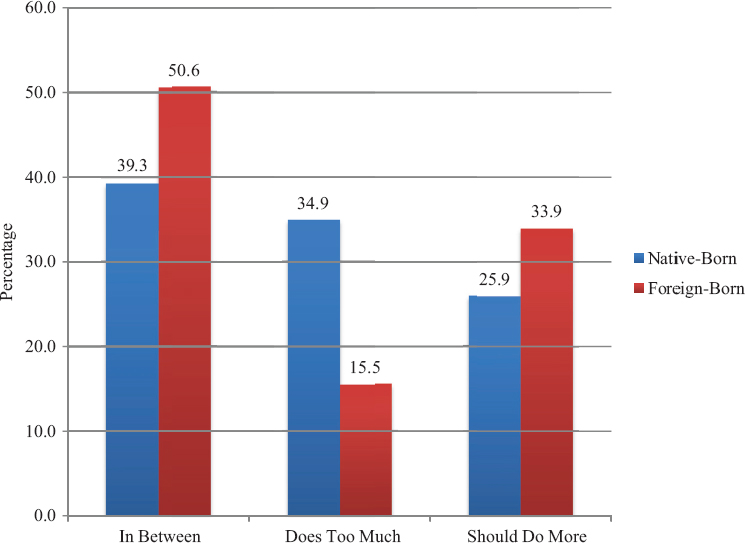

SOURCE: Data from General Social Survey.

The Role of Government

The proper role of the federal government, meanwhile, is a central issue in most national policy debates and has become an increasingly salient issue in political campaigns (see Figure 7-2).3 On average about one-third of the native-born agree that “the government in Washington is trying to do too many things that should be left to individuals and private businesses” and one quarter disagree, stating that the government should do more to help with the country’s problems. Immigrants tend to diverge from the native-born on this issue, as they are significantly more likely to believe that the government should do more (36%) than to believe that it does too much (15%)—a near reversal of the opinion from the native-born. The largest percentage of both immigrants and the native-born held opinions that fell somewhere in between these two more extreme positions, and in fact immigrants were much more likely to be in the middle.

___________________

3 See http://www.ropercenter.uconn.edu/pdf/Health%20care%20issue.pdf [November 2015].

Same-sex Marriage

Dramatic shifts have occurred in American public attitudes toward the acceptance of same-sex marriage in the last two decades, an issue that remains contested in U.S. society, despite the recent Supreme Court ruling (Obergefell v. Hodges 576 U.S.__, 2015) striking down laws limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples. In the 2000 and 2004 elections, same-sex marriage was used as a “wedge issue” in several states, perhaps helping Republican candidates in closely contested local races and in the race for the White House (Taylor, 2006). However, in the years since those elections, the American public’s views on gay rights have changed at a rapid pace, with support for “marriage equality” increasing from little more than 10 percent in 1988, when the GSS first began asking about whether homosexuals should have the right marry, to 56 percent in 2014.4 The extent to which foreign- and native-born opinions about gay marriage are generally moving in the same direction is therefore an interesting indicator of immigrant integration.

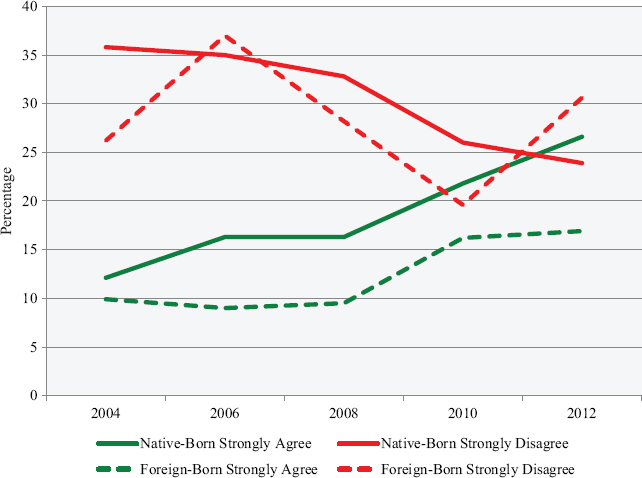

Response patterns over time are similar for both the native born and the foreign born. The percentage of respondents in both groups who thought that same-sex couples should be allowed to marry trended up between 2002 and 2012, from 12 percent to 59 percent for the native-born and from 17 percent to 36 percent for the foreign-born (see Figure 7-3). Also, the percentage of both groups who oppose same-sex marriage has generally trended downward, in particular for respondents who say they highly disagree with the statement that same-sex couples should be allowed to marry. Further research indicates that the same trend holds true for Latinos and Asians more generally, suggesting that the views of second and higher generation immigrants are evolving in the same direction as those of higher-generation native-born Americans in general on this issue (Abrajano, 2010; Lewis and Gossett, 2008; Lopez and Cuddington, 2013).

The American Dream

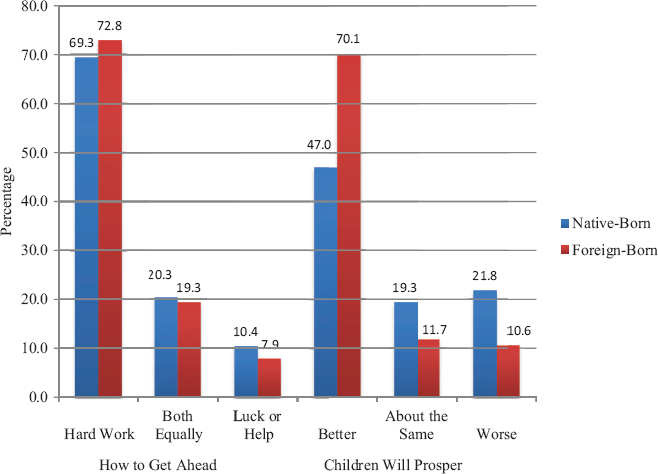

One way in which immigrants may be more American than the native-born is in their steadfast belief in the American dream. The foreign-born are increasingly likely to believe that their children’s standard of living will surpass theirs. In 2014, almost 70 percent voiced this optimism (up from 60% in 1994). The percentage of native-born who feel their children will prosper relative to their parents remains much lower, even though it rose slightly from 47 percent in 1994 to 50 percent in 2014. Majorities of both

___________________

4 See http://www.apnorc.org/PDFs/SameSexStudy/LGBT%20issues_D5_FINAL.pdf [November 2015].

SOURCE: Data from General Social Survey.

SOURCE: Data from General Social Survey.

the native-born and foreign born agree that hard work is the key to getting ahead economically (see Figure 7-4).

Overall, both survey data and the research on public attitudes indicate that immigrants, their descendants, and the general population of native-born Americans are not far from one another when it comes to attitudes and beliefs about social issues, and as immigrants and their descendants spend more time in the United States, even these differences diminish. If anything, immigrants are more optimistic about their prospects for success and less tied to partisan politics—attitudes that may further assist their sociocultural integration. Unfortunately, there are few data on how the attitudes immigrants bring with them affect the values and beliefs of the native-born, and this is an area that deserves further research (for information on native-born attitudes toward immigration, see Chapter 1).

LANGUAGE

The vast majority of Americans (over 90%), regardless of nativity status, agree that it is very or fairly important to be able to speak English. In a Pew Research Center/USA Today survey from June 2013, 76 percent of Americans said that they would require learning English as a precondition for immigrant legalization (Pew Research Center, 2013).5 English-language acquisition is both a key indicator of integration (Bean and Tienda, 1987) and an underlying factor that impacts one’s ability to integrate in other domains.

Language is also a sensitive topic that continues to be an important component in debates over immigration and immigrant integration. While one side of the debate views English as central to social cohesion and sees other languages and their speakers as a threat to American cultural dominance and native-born power, the other side argues that linguistic diversity and bilingualism contribute to American dynamism and aid innovation (Huntington, 2004; Alba, 2005). In fact, language diversity has grown with the immigrant population: since 1980, there has been a 158 percent increase in the number of residents who do not speak English at home (Ryan, 2013; Gambino et al., 2014). However, this diversity and concerns about its effects are not new. Similar debates and rhetoric emerged during earlier immigration waves (Crawford, 1992; Foner, 2000). As Rumbaut and Massey (2013) pointed out, the revival of immigration after the 1960s has simply restored language diversity to something approaching the country’s historical status quo. The major difference, discussed below, is the prevalence and perhaps endurance of Spanish.

___________________

5 See http://www.people-press.org/files/legacy-pdf/6-23-13%20Immigration%20Release%20Final.pdf November 2015].

Language has a strong and well-demonstrated effect on the ability of immigrants and their descendants to integrate across various social dimensions. Recent research has documented how English proficiency affects employment opportunities and earnings (Batalova and Fix, 2010; Bleakley and Chin, 2004; Borjas, 2013; Chiswick and Miller, 2009; Hamilton, 2014; Shin and Alba, 2009; Wilson, 2014) and educational outcomes (Bleakley and Chin, 2008; Kieffer, 2008; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2008, 2010). Lack of English ability limits residential choices (Iceland and Scopilliti, 2008; Toussaint-Comeau and Rhine, 2004) and even foreign accents can lead to housing discrimination (Purnell et al., 1999; Massey and Denton, 1987). Difficulty in communicating effectively with health care providers and social isolation have been found to negatively affect immigrants’ health and socioemotional well-being (Kang et al., 2014; Yoo et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2012). Language ability also mediates the exposure of immigrants and their descendants to mainstream American culture, influencing, for instance, marriage patterns (Duncan and Trejo, 2007; Oropesa and Landale, 2004; Stevens and Swicegood, 1987) and fertility decisions (Lichter et al., 2012; Swicegood et al., 1988). And it affects their ability to engage in native civic organizations, understand political discourse, and naturalize (Bloemraad, 2006; Chenoweth and Burdick, 2006; Stoll and Wong, 2007).

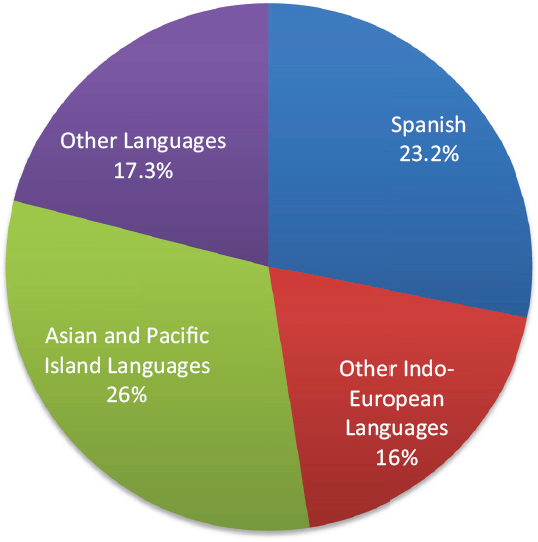

A major source of concern is what the Census Bureau and other researchers term “linguistic isolation.” Households are linguistically isolated when none of their adult members (over age 14) speak English very well (Siegel et al., 2001). In 2013, 4.5 percent of households in the United States were linguistically isolated. The largest proportion of such households was Asian and Pacific Islander, followed by households speaking Spanish (see Figure 7-5). In addition, 22 percent of children living in immigrant families in 2013 lived in linguistically isolated households.6 Linguistic isolation has important implications for immigrant and second generation integration, because it limits immigrants’ social capital and their access to various resources; it also contributes to anxiety (Nawyn et al., 2012). Children from linguistically isolated households are more likely to be in English-Language Learner (ELL) classes and to face higher barriers to educational attainment due to their parents’ limited ability to communicate with school staff and monitor their children’s educational progress (Batalova and Fix, 2010; Fix and Capps, 2005; Gifford and Valdes, 2006). Linguistically isolated house-

___________________

6 “Children in immigrant families” are children who are themselves foreign-born or are living with at least one foreign-born parent. For more information and data sources, see http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/129-children-living-in-linguistically-isolatedhouseholds-by-family-nativity?loc=1&loct=2#detailed/2/2-52/true/36,868,867,133,38/78,79/472,473 [November 2015].

SOURCE: Data from 2013 American Community Survey.

holds are also more likely to be impoverished, which has negative consequences for children’s cognitive abilities (Glick et al., 2013). High levels of linguistic isolation in new immigrant destinations have also been linked with higher homicide rates for Latinos (Shihadeh and Barranco, 2010).

Notably, the importance of English proficiency does not negate the potential positive effects of bilingualism. Retention of parents’ mother tongue in the second generation is linked to better educational outcomes (Bankston and Zhou, 1995; Olsen and Brown, 1992; Portes and Rumbaut, 2001) and expanded opportunities for employment (Hernandez-Leon and Lakhani, 2013; Morando, 2013). Although there may currently be limited economic returns to bilingualism (Saiz and Zoido, 2005; Shin and Alba, 2009), this may change in the face of increasing globalization. Various studies have found that bilingualism is associated with positive cognitive outcomes, including increased attentional control, working memory, metalinguistic awareness, and abstract and symbolic representation skills (Adesope et al., 2010). And bilingualism may benefit children’s social and emotional health (Halle et al., 2014).

Language Integration in the Immigrant Generation

The languages spoken by immigrants at home reveal contemporary linguistic diversity. In 1980, the first time the decennial census included the household language question, 70 percent of the foreign-born spoke a language other than English at home.7 Twenty-eight percent of these respondents spoke Spanish, which was already the largest foreign-language group in the United States. By 2012, 85 percent of the foreign-born population spoke a language other than English at home (Gambino et al., 2014, p. 2). Sixty-two percent spoke Spanish at home, while Chinese languages came in a distant second at 4.8 percent (Ryan, 2013). Just over three-fourths of both Latinos and Asians spoke a language other than English at home, compared to 6 percent of non-Hispanic whites (Johnson et al., 2010). However, there was significant variation by country of origin: more than 90 percent of Dominicans, Guatemalans, and Salvadorans spoke Spanish at home, while Colombians and Mexicans matched the average for Latinos. Among Asians, 89 percent of Vietnamese spoke a non-English language at home, compared to only 46 percent of Japanese (Johnson et al., 2010). There are also regional and state variations, with significantly higher proportions of the foreign-born in Texas, California, Illinois, Nebraska, New Mexico, and Nevada speaking a language other than English at home (Gambino et al., 2014, p. 4).

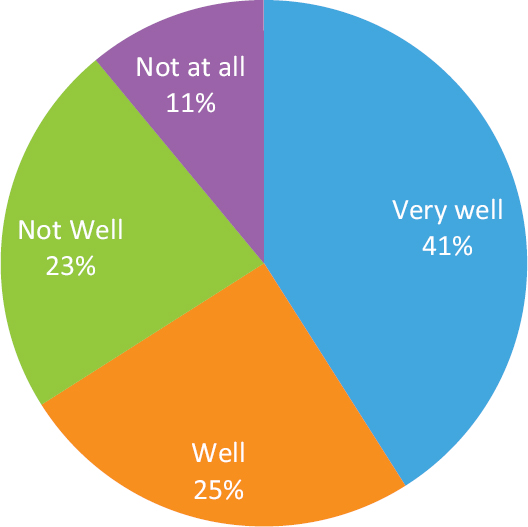

The current data on English proficiency indicate that 66 percent of the foreign-born who use a foreign language at home speak English “very well” or “well,” 23 percent speak it “not well, and 11 percent speak English “not at all” (see Figure 7-6) (Gambino et al., 2014, p. 3). The foreign-born from Latin America and the Caribbean generally have lower English-language proficiency compared to immigrants from other regions and are most likely to speak English “not at all” (Gambino et al., 2014, p. 7).

English-language proficiency among immigrants is strongly correlated with age of arrival (Bleakley and Chin, 2010); and duration of stay in the United States (Batalova and Fix, 2010). Not surprisingly, immigrants who arrive as young children and those who have resided in the United States for longer periods tend to speak English well (Stevens, 2014). Citizenship status (Johnson et al., 2010) and education are also positively associated with English proficiency (Gambino et al., 2014). In addition, English-language ability is strongly associated with occupational status in the United States (Akresh et al., 2014). Other research indicates that place of settlement (Singer, 2004); household context (Thomas, 2010); and gender (Batalova

___________________

7 See https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0029/tab05.html [November 2015].

SOURCE: Data from 2013 American Community Survey; Gambino et al. (2014).

and Fix, 2010; Thomas, 2010; Hernandez-Leon and Lakhani, 2013) also influence immigrants’ English-language abilities.

Despite popular concerns that immigrants are not learning English as quickly as earlier immigrants, the data on English proficiency indicate that today’s immigrants are actually learning English faster than their predecessors (Fischer and Hout, 2008). One factor is the increase in English-language acquisition before migration. Many of today’s immigrants arrive from countries where English is the official or common language, including migrants from the English-speaking West Indies, India, Pakistan, the Philippines, and former British colonies in West Africa such as Nigeria and Ghana. Immigrants from these countries are often well educated and relatively highly skilled (Anderson, 2015). In addition, English has become the lingua franca of international trade and politics (Crystal, 1997; Pennycook, 2014), and is embedded in many non-English speaking cultures, especially among those in the higher tiers of the economy and polity (Park, 2009; Song, 2010). English is now taught in primary and secondary schools across the world (e.g., Warschauer, 2000). Akresh and colleagues (2014) found

that experience with English is common among immigrants from non-English speaking countries, with 38 percent of new legal immigrants saying they had taken a class in English and nearly everyone having consumed at least one form of English-language media prior to departure. These experiences yielded a 48 percent rate of English proficiency upon arrival.

Language Integration Across Generations

If the rate of language integration among the foreign-born over the course of their lifetime is important, the rate of linguistic integration across generations is just as significant. The current evidence suggests that the second and third generations are integrating linguistically at roughly the same rates as their historical predecessors, with complete switch to English and loss of the ability to speak the immigrant language generally occurring within three generations (Alba et al., 2002; Alba, 2005; Portes and Hao, 1998). However, there are differences based on immigrants’ first language; specifically, Spanish-speakers and their descendants appear to be integrating more slowly in terms of both gaining English language and losing the ability to speak the immigrant language than other immigrant groups (Alba, 2005; Borjas, 2013).

A major reason is the larger size and frequent replenishment of the Spanish-speaking population in the United States (Linton and Jimenez, 2009). As noted above, Spanish is by far the most common non-English household language in the United States due to the enormous increase in immigration from Spanish-speaking countries since 1970. Spanish speakers appear to become English proficient at a slower pace than other immigrants (Alba, 2005; Borjas, 2013). Bilingualism is more common among second generation Latinos, and English monolingualism is less common, than it is for Asians and Europeans in the third generation (Alba, 2005; Portes and Schauffler, 1994; Telles and Ortiz, 2008). Thomas (2011) found that among descendants of Caribbean immigrants, the transition to English monolingualism was faster for French speakers than for Spanish speakers.

Even so, Rumbaut and colleagues (2006), using data IMMLA and CILS data from Southern California, show that the vast majority of children of Spanish-speaking immigrants are fluent in English and that by the third generation most are monolingual English speakers. Even in the large Spanish-speaking concentration in Southern California, Mexican Americans’ transition to English dominance was all but complete by the third generation: only 4 percent still spoke Spanish at home, although 17 percent reported they still spoke it very well (Rumbaut et al., 2006). And although most Mexican Americans favor bilingualism, Spanish fluency is “close to extinct” by the fifth generation (Telles and Ortiz, 2008, p. 269). Although the prevalence of Spanish among immigrants is historically exceptional, the

extent to which this impedes English proficiency or encourages its retention in succeeding generations remains an open question.

Ethnic and Foreign-Language Media

Ethnic and foreign-language media has a long and storied history in the United States: Benjamin Franklin printed the first German-language Bible in the United States, in addition to widely available German hymnals and textbooks (Pavlenko, 2002). By the turn of the 20th century, “every major ethnic community had a number of dailies and weeklies,” many of which also published literary works and serialized novels (Pavlenko, 2002, p. 169). Today’s immigrants also have access to a range of foreign-language television channels, many originating in their native countries, as well as other channels, such as Telemundo and Univision, produced in the United States and with content specifically designed for residents of this country. Lopez and Gonzalez-Barrera (2013) found that a majority of Latino adults say they get at least some of their news in Spanish, although that number was declining. And while the panel found no comparable data on general news consumption among Asian Americans, Wong and colleagues (2011) reported that the consumption of news about politics shows a significantly higher proportion of Asian Americans than Latino Americans who get their political news exclusively in English.

Foreign-language media can play a role in immigrant integration, although it may simultaneously impede or slow down assimilation. For instance, Zhou and Cai (2002) find that while Chinese language media may contribute to ethnic isolation, it also helps orient recent immigrants to their new society and promotes social mobility goals like entrepreneurship and educational achievement. Felix and colleagues (2008) suggested that Spanish-language media may play a role in encouraging immigrants to mobilize politically and eventually naturalize. And Shah and Thornton (2003) noted that while mainstream media coverage of interethnic conflict and immigration tended to reinforce the dominant racial ideology and fears about immigration, ethnic newspapers provided their readers with an alternative perspective to this ideology and its associated fears about immigrants. The extent to which ethnic and foreign-language media may promote social and economic integration, even as it helps immigrants maintain their native language and ties to their country of origin, is an issue that needs to be studied further.

Two-Way Exchange

Absent from most discussions about language and immigrant integration is the two-way exchange between American English and the languages

immigrants bring with them. Evidence of this two-way exchange occurs in education trends and in additions to American English itself. Dual language and two-way immersion programs in languages such as Spanish and Chinese that include both native-born English speakers and first or second-generation Limited English Proficient (LEP) students are becoming increasingly popular (Fortune and Tedick, 2008; Howard et al., 2003). And enrollment in modern foreign-language courses in colleges and universities has grown since 2002 (Furman et al., 2010). Spanish course enrollments are by far the largest, but there has been significant growth in enrollment for Arabic, Chinese, and Korean, even as enrollment in classical languages has fallen (Furman et al., 2010). It is unclear whether native-born Americans are becoming proficient in these languages, but a majority of Americans feel that learning a second language is an important, if not necessarily essential, skill (Jones, 2013).

Other evidence of two-way exchange includes the incorporation of words or expressions into American English. Linguistic “borrowing”, in which words or parts of words are imported or substituted, is a common phenomenon when languages come into contact (Appel and Muysken, 2005). Just as expressions such a “kosher” and “spaghetti” became common after large waves of Jewish and Italian immigrants arrived at the turn of the 20th century (Thomason and Kaufman, 1988), today native-born Americans may serve “guacamole” at Super Bowl parties or take their children to taekwondo. In addition, there are “hybridized” linguistic expressions and dialects that combine English and other languages, most notably Spanglish but also “Hinglish”(Hindi and English) and “Taglish” and “Englog” (Tagalog and English) that immigrants from countries formerly colonized by English-speaking nations bring with them to the United States (Bonus, 2000; Lee and Nadeau, 2011; Perez, 2004; Stavans, 2003). It is also worth noting here that, according to a recent analysis by the Pew Research Center, 2.8 million non-Hispanics speak Spanish at home, the majority born in the United States and with ancestry in non-Spanish speaking countries (Gonzalez-Barrera and Lopez, 2013). Although it is unclear why so many non-Hispanics speak Spanish at home (many may be married to Hispanics), this number reconfirms that Spanish holds a special place in the American linguistic landscape.

Conclusion

The current research on language integration suggests that today’s immigrants and their descendants are strikingly similar to previous waves of immigrants, despite the differences in their countries of origin and the dominance of Spanish among current immigrants. The panel agrees with Rumbaut and Massey (2013, p. 152) who concluded that the mother

tongues of immigrants today will probably “persist somewhat into the second generation, but then fade to a vestige in the third generation and expire by the fourth, just as happened to the mother tongues of the southern and eastern European immigrants who arrived between 1880 and 1930.” Although the Spanish-speaking second and third generations may retain their dual language abilities longer than others, Rumbaut and Massey (2013, pp. 152-153) pointed out that even in Southern California, Spanish effectively dies out by the fourth generation, and Asian languages disappear even faster. Meanwhile, as discussed above, an increasing number of native-born Americans are learning the languages immigrants bring with them, while immigrant cultural forms and expressions continue to alter the American cultural landscape.

Although the outlook for linguistic integration is generally positive, the lack of English proficiency among many in the recently arrived first generation, particularly in low-skilled, poorly educated, and residentially segregated immigrant populations, coupled with barriers to English acquisition, can impede integration. Funding for English-language classes has declined even as the population of limited English proficient residents has grown (Wilson, 2014). Tellez and Waxman (2006) found significant state variation in English as a second language (ESL) certification of primary and secondary school teachers and how schools manage ESL education. Batalova and Fix (2010) reported that the supply of adult ESL and basic skills learning opportunities has not kept up with demand; nearly two-thirds of immigrants with very limited English proficiency had never taken an ESL class. As discussed in Chapter 2, ESL instruction is most readily available for refugees, and the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act was explicitly designed to address the needs of adult English language learners. But there are barriers to receiving English-language education, particularly for low-income immigrants (see Chapter 2). Delays in English-language acquisition significantly diminish immigrants’ ability to integrate across various dimensions and may have long-term deleterious effects not only on their opportunities but also on their children’s life chances.

RELIGION

Religion and religious institutions have long helped immigrants adjust to American society and have facilitated the integration process for immigrants and their descendants. This was true a hundred years ago, when the vast majority of immigrants were from Europe, and is still true today, when immigrants mostly come from Latin America, Asia, and the Caribbean. The integration of the descendants of turn-of-the-20th-century eastern, southern, and central European immigrants and eventual acceptance of their predominant religions—Catholicism and Judaism—into the

American mainstream helped to create a more welcoming environment for non-Western religions that a minority of immigrants bring with them today.

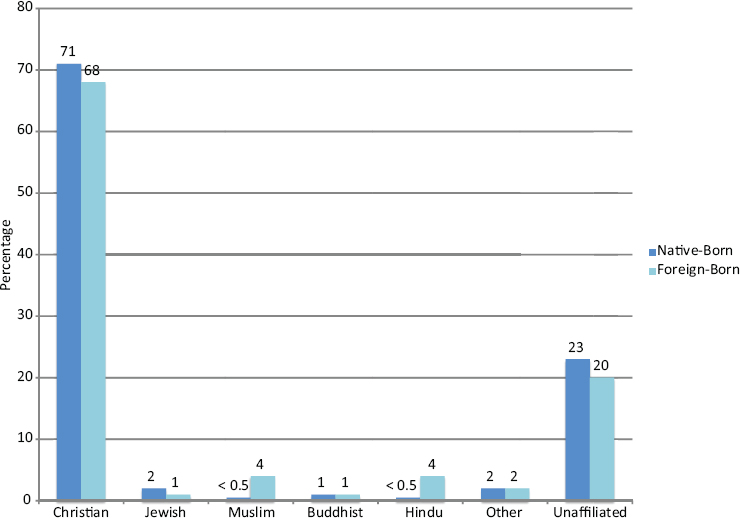

Because the U.S. Census Bureau is not allowed to ask questions on religious affiliation, researchers have to rely on various other surveys for data on immigrants’ religious affiliations. In 2014, according to one survey, the vast majority of immigrants—68 percent—were Christian, while 4 percent were Muslim, 4 percent Buddhist, 3 percent Hindu, 1 percent Jewish, and 2 percent a mix of other faiths (Pew Research Center, 2015) (see Figure 7-7). Immigrants are more Catholic than the U.S.-born (39% foreign-born adults are Catholic versus 18% of U.S-born adults) and less Protestant (foreign-born adults are about half as likely, 25%, to be Protestant as are U.S.-born adults, 50%) (Pew Research Center, 2015). This is not surprising given the high proportion of immigrants from predominantly Catholic Latin America and the significant numbers of Catholics from other countries such as the Philippines. Interestingly, foreign-born Protestants have a much

SOURCE: Data from Pew Research Forum (2015). Available: http://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/chapter-4-the-shifting-religious-identity-of-demographic-groups/pr_15-05-12_rls_chapter4-01/ [November 2015].

lower tendency to belong to evangelical groups (16%) than do U.S.-born Protestants (28%), although a survey of very recent arrivals found a much higher fraction (41%) identifying as Evangelical or Pentecostal. A large proportion came from Central America, where evangelical Protestants have made substantial inroads in recent years (Pew Research Center, 2014). In a 2013 Pew survey, 16 percent of foreign-born Latinos identified as evangelical Protestant, about half of them becoming “born again” after coming to the United States (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2008; Massey and Higgins, 2011; Pew Research Center, 2014).

The post-1965 immigration has led to the growing prominence of new religions on the American landscape. According to the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (2011), 63 percent of the nation’s estimated 2.75 million Muslim Americans are first generation immigrants and 15 percent are second generation (about one in eight Muslim Americans in 2011 were African Americans). Around 40 percent of Muslim Americans are from the Middle East and North Africa, and about a quarter are from the South Asian region (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2011). A total of 86 percent of the nation’s Hindus, and a quarter of the Buddhists, are foreign-born. Most Hindu immigrants are from India, while immigrant Buddhists are mostly from Vietnam, with a significant proportion from China (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2008).

How religious are immigrants? In 2014, 80 percent of immigrants were affiliated with a religious group or faith, compared to 77 percent of the U.S.-born (Pew Research Center, 2015). Unfortunately, we know little about the strength of religious beliefs among those who are affiliated. Data on religious service attendance is available from the New Immigrant Survey (NIS) of immigrants receiving permanent residence documents in 2003. Overall, a little more than a quarter (27%) of all Christian immigrants in the survey (30% of Catholics and 22% of Protestants) attended religious services once or twice a month, with about the same percentages never attending; the percentages never attending were much higher for Muslims (68%) and Buddhists (68%) (Massey and Higgins, 2011). By comparison, about six in ten (62%) of all Christians in the United States say they attend religious services at least once or twice a month (Pew Research Center, 2013). However, other research found that some immigrant groups did show high rates of church attendance. Massey and Higgins (2011) reported that 70 percent of Korean Protestant immigrants and around 40-50 percent of Filipino and Vietnamese Catholics and Salvadoran Protestants attend religious services at least four times a month.

According to the NIS data, for every major religious group (except Jews), immigration was associated with a drop in the frequency of religious service attendance in the United States. In all the groups, the percentage never attending religious services rose in the United States, with especially

high levels of nonattendance among non-Christians, more than two-thirds for Muslims and Buddhists. The NIS study also found low rates of congregational membership among the recently arrived non-Christian immigrants (10%) as well as Catholics (19%) as compared to nearly half (49%) of Protestants.

The declines in religious attendance may reflect reduced access to appropriate religious facilities in the United States as well as the disruptive experience and time-consuming process of initial settlement and long hours spent at work. Some immigrants do not intend to stay permanently, so they may be less motivated to get involved in religious groups (Massey and Higgins, 2011). An open question is whether, and to what extent, immigrants become more involved in religious groups the longer they reside in and become more used to life in the United States. The data on Muslim immigrants cited below do point in this direction.

Among the second generation, a substantial minority appear to be engaged with religious congregations, although here, too, the data are limited. One source is the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study, which is conducted in San Diego and south Florida and is heavily weighted toward Catholics, given the high proportion of Latin Americans and Filipinos in these areas (Portes and Rumbaut 2001). More than 50 percent of the children of immigrants interviewed in the third wave of the study (when the average age of the cohort was 24) were Catholic, fewer than 10 percent were Protestant. While nearly 20 percent in the survey never took part in religious services, about a third were regular church-goers, attending at least once a month (more than a fifth attended at least once a week). The most regular attenders were Afro-Caribbeans, especially Haitians; Chinese and other Asians (Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese, although not the mostly Catholic Filipinos) had very high rates of nonattendance (Portes and Rumbaut 2014). Other research points to high rates of church involvement among young adults with Korean immigrant parents; in a New York survey, more than 80 percent of 1.5 generation and second generation Korean Protestants attended church once a week or more (Min, 2010, p. 139).

Role of Religious Institutions in Integration

Historical studies of U.S. immigrants argued that religious participation helped turn European Jewish and Catholic immigrants into Americans in the past, with Will Herberg (1960, pp. 27-28) famously writing that it was “largely in and through . . . religion that . . . the immigrant], or rather his children and grandchildren, found an identifiable place in American life.” Herberg’s themes continue to have relevance today, as a substantial share of contemporary immigrants “become American” through participating in religious and community activities of churches and temples. Religion

provides a way for many immigrants to become accepted in the United States—or, perhaps more accurately, religious institutions are places where they can formulate claims for inclusion in American society (Portes and Rumbaut, 2014; Alba et al., 2009).

Membership in religious groups offers immigrants the “3Rs”: a refuge (a sense of belonging and participation in the face of the strains and stresses of adjusting to life in a new country); an alternative source of respectability for those who feel denied social recognition in the United States; and an array of resources such as information about jobs, housing, and classes in English (Hirschman, 2004; see also Ebaugh and Chafetz, 2000; Menjívar, 2003; Min, 2001). For many immigrants, religious groups represent one of the most welcoming institutions in the new society (Alba and Foner, 2015). Religious groups can be a place where immigrants build a sense of community and receive material help and emotional solace (Hirschman 2004). Central American religious communities in the United States represent continuity, since immigrants may join a church of the same, or a similar, denomination or faith community as they belonged to back home (Menjívar, 2003). But they also enable change, as these immigrants become involved with new institutions and new co-worshippers in this country. In fact, some Latin American immigrants have left Catholicism for smaller evangelical churches that provide more opportunity to develop personal and supportive relationships than do larger Catholic or mainline Protestant congregations (Menjívar, 1999, 2003).

Immigrant churches, mosques, and temples can, in addition, build civic skills, encourage active civic engagement, and provide a training ground for leadership; some provide citizenship classes and programs to register people to vote and encourage volunteer services in the wider community (Foley and Hoge, 2007). As discussed in Chapter 2, many of the organizations that partner with the federal government to assist refugees are religiously affiliated. In some cases, religious groups increase the second generation’s upward mobility prospects by providing a variety of classes, including in English and SAT preparation. Even classes in home-country languages can encourage habits of study (Lopez, 2009). Involvement in church may also shield young people from gangs and negative aspects of American culture (Zhou and Bankston, 1998) and some churches have developed programs that explicitly target youth at risk of engaging in drugs or gangs (Menjívar, 2002). While Catholic parochial schools have provided a pathway to upward mobility for some of the second generation in the Northeast and Midwest today, as they did for many Irish and Italian Americans in the past (Kasinitz et al., 2008), the Catholic school system, only weakly developed in the Southwest, did not operate this way for the Mexican second generation there in earlier years, and it has not been doing so today (Lopez, 2009).

Furthermore, asserting a religious identity may be an acceptable way

to be different and American at the same time, a dynamic captured by the title of Prema Kurien’s article, “Becoming American by Becoming Hindu” (1998) (see also Kibria, 2011). Menjívar (2002) asserted that religious involvement may enable second generation Central American youth to better appreciate their parents’ origins while also helping them to navigate their place in the United States. At the same time, there is a trend toward Americanization—and the development of congregational forms—in immigrant religious institutions as leaders often consciously attempt to become more “American” in response to the exigencies of everyday life, including immigrants’ work schedules (Warner and Wittner, 1998; Ebaugh and Chafetz, 2000; Kibria, 2011). Muslim women are much more likely to attend Friday prayers at a mosque than in their home countries, and English is often used at least some of the time in many congregations (Connor, 2014). In addition, some immigrants, as surveys of Asian Americans indicate for the Korean and Chinese communities, have converted to Christianity, many after they arrived in the United States (Kasinitz et. al., 2008; Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2012b).

Another issue related to integration concerns the extent to which immigrants, especially Christians, worship and thus have opportunities to mix with long-established native born Americans in religious congregations. Ethnographic studies suggest a predominant pattern of Asian and Latino immigrants worshipping with their own group, although these studies are selective (Kasinitz et.al. 2008; Chai Kim, 2006). There is also evidence from in-depth studies that religious groups can foster pan-ethnic ties and identities. For example, a study of Salvadoran immigrants frequenting large Catholic churches found that as they prayed with other Latinos, pan-ethnic (Latino) sentiments developed and strengthened among church members (Menjívar, 1999). Language, culture, and social networks are among the factors drawing Asian and Latino immigrants to Protestant and Catholic ethnic (and among Latinos, pan-Latino) congregations; their U.S.-born children may continue to feel more comfortable in ethnic or pan-ethnic congregations in adulthood, as is the case among many second generation Korean Protestants in the New York and Boston areas who attend Korean churches with services and programs available in English (Chai, 1998; Min, 2010). Just how common this pattern is among the second generation in other heavily Protestant (or Catholic) immigrant-origin groups is uncertain.

Muslim Immigrant Integration

Of particular interest when it comes to non-Western religions is the relation between Islam and integration into U.S. society. Research on Muslim Americans reveals signs of considerable integration although, at the same time, prejudice remains a barrier. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public

Life report on Muslim Americans (2011) found high rates of naturalization among the first generation; 70 percent of foreign-born Muslims were naturalized citizens (95% of those who came in the 1980s and 80% of those arriving in the 1990s). The Muslim foreign-born also had high educational attainment: nearly a third (32%) had graduated from college and a quarter were currently enrolled in college or university classes. Thirty-five percent of foreign-born Muslims had annual household incomes of at least $50,000, with 18 percent over $100,000—about the same as the general public. According to the Pew survey, religion is very important in the lives of Muslim immigrants and their children: 65 percent of the first generation and 60 percent of the second generation (i.e., native-born non–African Americans) perform the Salah, or ritual prayer, every day; 43 percent of the first generation and 47 percent of the second attended services at a mosque at least once a week. Nearly a third (30%) of foreign-born Muslim women in the United States reported always wearing a head cover or hijab when out in public.

At the same time, the Pew Research Center report revealed signs of growing Muslim American involvement in American society. As Kibria (2011, p. 57) noted, many Islamic American leaders have encouraged Muslim Americans to “assert their rights as Americans and claim their American identity.” In the Pew survey, 57 percent of foreign-born Muslims said they wanted to adopt U.S. customs and ways of life, although about half of the foreign-born (48%) and second generation (51%) thought of themselves first as Muslim rather than American (to put this in context, 46% of Christians in the United States think of themselves first as Christian). Among foreign-born Muslims, 53 percent said that all or most of their close friends were Muslim. The survey revealed strong support among Muslim Americans of both generations for women working outside the home (90%); most (64%) saw little support among Muslim Americans for violence and extremism.

Less happily, many (37% of foreign-born Muslims and 61% of non–African American native-born Muslims) reported being victims of one or more acts of hostility in the past year because they were Muslim. A smaller proportion of native-born non–African American Muslims (37%) than immigrants (58%) said that Americans were friendly to Muslim Americans.

Evidence from surveys of native-born Americans reveals unease among a minority about the non-Christian religions increasingly in their midst. In a 2002-2003 national survey reported by Wuthnow (2005), about a third of respondents said they would not welcome a stronger presence of Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists in the United States. About 4 in 10 said they would not be happy about a mosque being built in their neighborhood (about a third also would be bothered by the idea of a Hindu temple being nearby), and almost a quarter favored making it illegal for Muslim groups to meet

(a fifth in the case of Hindus or Buddhists). In a 2009 Gallup poll, more than 40 percent Americans said they felt at least a little prejudice toward Muslims, more than twice the number who said the same about Jews (Gallup Center for Muslim Studies, 2010).

Since the September 11, 2011, terrorist attacks (9/11), cases of discrimination, hate crimes, and bias incidents against Muslims have increased. Indeed, anti-Muslim discourse is acceptable in American public life in a way that no longer is true for anti-black rhetoric (Alba and Foner, 2015). Yet religion has not become a deep divide between contemporary immigrants and the native-born in the United States as it has in much of western Europe, and religion is not a frequent subject of public debate about immigrant integration (Alba and Foner, 2015). By and large, religion is an accepted avenue for immigrants and their children’s inclusion in American society. Immigrant debates in the United States, according to Cesari (2013), have not been Islamicized, or systematically connected with anti-Islamic rhetoric, as they have been in western Europe. Alba and Foner (2015) found that, in the United States, Muslims are often framed as an external threat, as an enemy from outside the country committing acts of terrorism and threatening national security, not as an enemy from within undermining core national values, which is a view they said looms larger in western Europe.

Alba and Foner (2015, 2008) suggested three reasons for this difference:

- Only a tiny proportion of the foreign-born are Muslim in the United States as compared to Europe. Also, unlike in Europe, the migration flow of Muslims to the United States has been more selective, and Muslim immigrants have done fairly well, with many of them well-educated and in the middle class.

- The United States, characterized by unusually high levels of religious belief and behavior relative to much more secular western Europe, has less trouble recognizing claims based on religion.

- Historically rooted relations and arrangements between the state and religious groups in the United States, especially foundational Constitutional principles of religious freedom and separation of church and state, make it less difficult to incorporate and accept new religions than has been true in Europe, with its long history of entanglement of Christian religious institutions and the state.

Two-Way Exchange

As the data above suggest, immigrants are adding new diversity to the nation’s religious mosaic. Immigrants and their children are also adding new members to the Catholic church and to Protestant denominations, no doubt keeping some congregations alive, especially in numerous inner-city

and inner-suburban neighborhoods that, absent immigration, would have witnessed dramatic population decline (Foner, 2013; Singer, 2004). As the panel noted above, both the foreign-born and the U.S.-born are very likely to be religiously affiliated (80% and 77% respectively), and the proportion of religiously unaffiliated is growing at a faster pace among the native-born than among immigrants (Pew Research Center, 2015). Nationwide, almost a quarter of the Catholics in the United States are foreign-born, as are nearly two-fifths of the Greek and Russian Orthodox; only 5-7 percent of Protestants, mainline and evangelical, are foreign-born (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2008). Although secularism appears to be increasing for both groups, the stronger religiosity of the foreign-born means that immigrants may play an even larger role in sustaining religious organizations in the United States in the future.

As for the incorporation of non-Christian religions into the American mainstream, it is unclear whether history will repeat itself. When Catholic and Jewish immigrants arrived from Europe in the past, Protestant denominations were more or less “established” and they dominated the public square. Those earlier immigrants experienced virulent anti-Catholic nativism and anti-Semitism (Higham, 1955). By the mid-20th century, however, Jews and Catholics had been incorporated into the system of American pluralism and Americans had come to think in terms of a tripartite perspective—Protestant, Catholic, and Jew. The very transformation of the United States into a “Judeo-Christian” nation and the decrease in religious affiliation among the native-born has meant that post-1965 immigrants enter a more religiously open society than their predecessors did 150 years ago (Pew Research Center, 2015; Alba and Foner, 2015).

An important question is whether the new religions, and Islam in particular, will eventually attain the charter status now occupied by Protestanism, Catholicism, and Judaism. It is too early to tell. The ongoing controversies over zoning for mosques near Ground Zero in New York City and in localities across the country indicates that 9/11 continues to strongly influence Americans’ perception of Islam as an existential threat and Americans’ reception of Muslims in their communities (Cesari, 2013; Goodstein, 2010). Despite pockets of opposition, however, more than 40 percent of the mosques in the United States have been built just since 2000 (Pew Research Center, 2012). Although it took more than a century, the United States was able to overcome its fear of the “Catholic menace” in the past. This history offers hope that the nation may be able to do so with regard to Islam as well. Perhaps as the historian Gary Gerstle (2015) notes, we will be talking about America as an Abrahamic civilization, a phrase joining Muslims with Jews and Christians. We are at present a long way from that formulation of American national identity, but no further than America once was from the Judeo-Christian one.”

CRIME

Americans have long believed that immigrants are more likely than natives to commit crimes and that rising immigration leads to rising crime (Kubrin, 2014; Gallagher, 2014; Martinez and Lee, 2000). This belief is remarkably resilient to the contrary evidence that immigrants are in fact much less likely than natives to commit crimes. These contemporary beliefs have strong historical roots. Common stereotypes of immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were that immigrants were much more likely to be criminals than the native-born.

The criminal stereotype applied to a number of different ethnic groups. The term “paddy wagon,” slang for a police van to transport prisoners, began as an ethnic slur against the “criminal” Irish in the mid-19th century. Stereotypes about Italian Americans have focused on organized criminal activity and the mafia; but all southern and eastern European immigrants were commonly thought to bring crime to America’s cities. European immigrants were generally poor, and their neighborhoods were thought to be highly disorganized and anomic, leading to higher crime rates. Historical studies have shown that this belief was wrong (Moehling and Piehl, 2009). Then, as now, immigrants were less crime prone than native-born Americans.

Today, the belief that immigrants are more likely to commit crimes is perpetuated by “issue entrepreneurs” who promote the immigrant-crime connection in order to drive restrictionist immigration policy (Ramakrishnana and Gulasekaram, 2012; Gulasekaram and Ramakrishnan, 2015), and media portrayals of non-whites and immigrants as prone to violence and crime (Gilliam and Iyengar, 2000; Rumbaut and Ewing, 2007; Sohoni and Sohoni, 2014; Subveri et al., 2005). The criminalization of certain types of migration also contributes to this perception (see Chapter 3 for discussion of “crimmigration”). Although native-born Americans’ attitudes about immigration and immigrants are often conflicting (see Chapter 1), the negative perception of immigrants’ criminality continues to endure, potentially posing a barrier to integration, particularly for the first generation. The historical evidence suggests that immigrants’ descendants were able to overcome these negative stereotypes, but if Latinos, in particular, continue to be racialized and discriminated against, this stereotyping may present a more formidable barrier to their successful integration in the future.

An empirical assessment of the relationship between immigration and crime involves two key questions. First, are immigrants more likely than the native-born to commit crime? And second, do immigrants adversely affect the aggregate crime rate? Distinguishing between these two questions is critical (Mears, 2002, p. 285). For example, it is plausible that at the individual level immigrants are far less criminal than nonimmigrants but

that an influx of immigrants could cause increased crime among the native-born by disrupting the structure of local labor markets (Reid et al., 2005, p. 761) or by displacing other native-born minorities, which could lead to an increase in the criminality of the displaced groups (Wilson, 1996), in either case leading to an increase in the crime rate. In other words, immigrants may have an adverse effect on crime by crowding natives out of the legal employment sector and increasing criminal behavior among natives (Butcher and Piehl, 1998b; Reid et al., 2005).

The hypothesis that immigrants would be more likely to commit crime than natives at the individual level appears at least plausible to social scientists because immigrants have a number of characteristics associated with higher crime: they are disproportionately male and young. They also tend to have lower education levels and wages than the rest of the population (Butcher and Piehl, 1998a); both these factors are correlated with commission of crimes (Harris and Shaw, 2000).

While both ideas that immigrants themselves might be more likely to commit crime and that the presence of immigrants might be more likely to raise the crime rate in a given area, are plausible as hypotheses to examine, recent empirical evidence, discussed below, shows that both hypotheses are false. Immigrants are in fact much less likely to commit crime than natives, and the presence of large numbers of immigrants seems to lower crime rates.

The vast majority of research in this area has focused on the individual-level question of whether immigrants have higher crime, arrest, and incarceration rates than native-born individuals. In 1931, the National Commission on Law Enforcement, also known as the Wickersham Commission, devoted an entire report to the topic of “Crime and the Foreign-born,” reaching the conclusion that, when controlling for age and gender, the foreign-born committed proportionally fewer crimes than the native-born (National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement, 1931). Contemporary empirical studies continue to find that crime and arrest rates are lower among immigrants (Bersani, 2014; Butcher and Piehl, 1998a, p. 654; Hagan and Palloni, 1999, p. 629; MacDonald and Saunders, 2012; Martinez and Lee, 2000; Martinez, 2002; Olson et al., 2009; Sampson et al., 2005; Tonry, 1997). In an extensive review of the literature, Martinez and Lee (2000, p. 496) concluded that: “. . . the major finding of a century of research on immigration and crime is that immigrants . . . nearly always exhibit lower crime rates than native groups.”

Similarly, research reveals that the rate of judicial institutionalization in the United States is lower among immigrants than among the native-born. Butcher and Piehl (1998a, 2007), for example, report that among U.S. men 18-40 years old, immigrants were less likely than the native-born to be institutionalized (i.e., in correctional facilities, mental hospitals, or

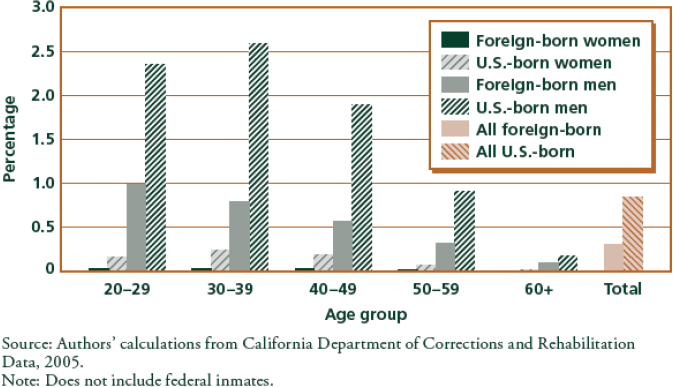

other institutions) and much less likely to be institutionalized than native-born men with similar demographic characteristics. They further noted that when controls are included for characteristics that correlate with labor market opportunities and criminal justice enforcement, “institutionalization rates are much lower for immigrants than for natives” (Butcher and Piehl, [1998a], p. 677, emphasis in original). A recent analysis of California incarceration rates by nativity status shows the dramatic differences between the foreign-born and U.S.-born (see Figure 7-8).

This finding on individual propensity to commit crime seems to apply to all racial and ethnic groups of immigrants, as well as applying over different decades and across varying historical contexts. Rumbaut and colleagues (2006) compared incarceration rates for the foreign-born and U.S.-born men, ages 18-39, and found that the incarceration of the foreign-born was one-fourth that of the native born. Rumbaut and Ewing (2007) compared the U.S.-born and foreign born incarceration rates in the 2000 census by racial ethnic groups. They found dramatic differences. Foreign-born Hispanic men had an incarceration rate that was one-seventh of U.S.-born Hispanic men. These large differences in rates held within specific Hispanic groups as well. Using 2010 ACS Census data, Ewing and colleagues (2015, pp. 6-7) found that 1.6 percent of immigrant males, ages 18-39, are incarcerated, compared to 3.3 percent of the native-born. And these figures include immigrants who were incarcerated for immigration violations. In other words, young native-born men are much more likely

SOURCE: Butcher and Piehl (2008). Reprinted with permission.

to commit crimes than comparable foreign-born men. This disparity also holds for young men most likely to be undocumented immigrants: Mexican, Salvadoran, and Guatemalan men. Ewing and colleagues (2015, p. 7) found that “[I]n 2010, less educated native born men age 18-39 had an incarceration rate of 10.7 percent—more than triple the 2.8 percent rate among foreign born Mexican men, and five times greater than the 1.7 percent rate among foreign born Salvadoran and Guatemalan men.” Sampson and colleagues (2005) studied crime by generation in Chicago neighborhoods for the period 1995-2002. They found that adjusting for family and neighborhood background, first generation immigrants were 50 percent less likely to commit crime than the third generation comparison group. And the second generation was 25 percent less likely to commit violent crime than the comparison group. This kind of finding has been called the immigrant paradox, or the “counterintuitive finding that immigrants have better adaptation outcomes than their national peers despite their poorer socioeconomic conditions” (Sam et al., 2006, p. 125) and “despite community conditions that sociologists traditionally associated with ‘social disorganization’” (Lee and Martinez, 2006, p. 90).

However, a related observation from this research is that the individual-level association between immigrants and crime appears to wane across generations. That is, the children of immigrants who are born in the United States have higher rates of judicial “offending” than the immigrant generation does (Lopez and Miller, 2011; Morenoff and Astor, 2006; Rumbaut et al., 2006 p. 72; Sampson et al., 2005; Taft, 1933). Although the second generation has higher crime rates than the first generation, their rates are generally lower than or very similar to the crime rate of the native-born in general (Berardi and Bucerius, 2014; Hagan et al., 2008; Bersani, 2014). Similarly, research has found that assimilated immigrants (defined as those who have been in the United States longer, those who are more fluent in English; and those who are likely to be naturalized citizens, and those who are more highly acculturated to the United States) have higher rates of criminal involvement compared to unassimilated immigrants (Alvarez-Rivera et al., 2014; Bersani, 2014). The risk of incarceration is higher not only for the children of immigrants but also for immigrants themselves, the longer they reside in the United States (Rumbaut and Ewing, 2007, p. 11). Butcher and Piehl (1998b) found that in both 1980 and 1990, those immigrants who arrived earlier were more likely to be institutionalized than were more recent entrants.

Findings such as these have led scholars to describe an “assimilation paradox” (Rumbaut and Ewing, 2007, p. 2), where the crime problem reflects “not the foreign born but their children” (Tonry, 1997, p. 20). Some researchers have suggested that the children of immigrants may have higher crime rates than their parents in large part because they are more assimi-

lated into American culture, including into “deviant subcultural values of youth gangs which young people joined as a source of self-identification and self-esteem” (Tonry, 1997, pp. 21-22). However, few studies have data available on first and second generation criminal behaviors, so the mechanisms that would account for the changes in crime rate are still unexplained (Berardi and Bucerius, 2013).

Immigration and the Crime Rate

Polling data show that Americans believe immigration increases crime at the aggregate level. Multiyear polling data by Gallup asking the following question: “Please say whether immigrants to the U.S. are making the crime situation better, worse, or not having much effect?” In 2001, before 9/11, 50 percent of polled respondents believed that immigrants will worsen the crime situation. By 2007 that response had reached 58 percent, with 63 percent of whites believing immigrants will worsen the crime situation in the United States. Nonetheless, a large body of evidence demonstrates that this belief is wrong. The research shows that immigration is associated with decreased crime rates at both the city and neighborhood levels.

The number of studies that examine the immigration-crime relationship across various levels of aggregation has grown in recent years. There have been numerous contemporary studies estimating the relationship between immigration and urban violent crime in the United States (Butcher and Piehl, 1998; 2007; Martinez, 2000; Reid et al., 2005; Piehl, 2007; Ousey and Kubrin, 2009; Stowell, 2010; Wadsworth, 2010; Bersani, 2010; Leerkes and Bernasco, 2010). All of these studies found that immigration inversely relates to crime rates: that is, the more immigrants in an area, the lower the crime rate tends to be. Using a wide range of methods, data, and levels of aggregation, these studies also found that the crime drop observed between 1990 and 2000 can partially be explained by increases in immigration. Although these studies include investigations of entire metropolitan areas and cities (Butcher and Piehl, 1998a; Martinez, 2000; Ousey and Kubrin, 2009; Reid et al., 2005; Stowell and Martinez, 2009; Wadsworth, 2010), more common are neighborhood-level studies that examine whether, and to what extent, immigration and crime are associated at a more local level. This literature has produced a fairly robust finding in criminology: areas, and especially neighborhoods, with greater concentrations of immigrants have lower rates of crime and violence, all else being equal (Akins et al., 2009; Chavez and Griffiths, 2009; Desmond and Kubrin, 2009; Feldmeyer and Steffensmeier, 2009; Graif and Sampson, 2009; Kubrin and Ishizawa, 2012; Lee and Martinez, 2002; Lee et al., 2001; MacDonald et al., 2013; Martinez et al., 2004, 2008, 2010; Nielsen and Martinez, 2009; Nielsen

et al., 2005; Stowell and Martinez, 2007; 2009; Velez, 2009; Kubrin and Desmond, 2014).

The finding that immigrant communities have lower rates of crime and violence holds true for various measures of immigrant concentration (e.g., percent foreign-born, percent recent foreign-born, percent linguistic isolation) as well as for different outcomes (e.g., violent crime, property crime, delinquency). The correlations of a variety of measures of immigration on homicide, robbery, burglary, and theft are consistent. “Even controlling for demographic and economic characteristics associated with higher crime rates, immigration either does not affect crime, or exerts a negative effect” (Reid et al., 2005, p. 775). Finally, the finding that areas with high concentrations of immigrants have lower rates of crime and violence holds true not just in cross-sectional but also in longitudinal analyses of the immigration-crime nexus (Ousey and Kubrin, 2009; 2014; Stowell and Martinez., 2009; Martinez et al., 2010; Wadsworth, 2010).

While the research is conclusive on the statistical relation between immigration and crime, there is still a lot to be learned because of limitations in the available data. The extent to which this relationship is truly generalizable or robust for all immigrant groups needs further study. Nearly all macro-level research focuses on “immigrant concentration,” generally defined as a single measure of immigrant concentration: the percentage of foreign-born in an area. Other studies combine several measures, such as percentage of foreign born, percentage who are Latino, percentage of persons who speak English not well or not at all, to create an “immigrant concentration index” (Desmond and Kubrin, 2009; Kubrin and Ishizawa, 2012; Lee and Martinez, 2002; Lee et al., 2001; Martinez, 2000; Martinez et. al., 2004, 2008; Morenoff and Sampson, 1997; Nielsen et al., 2005; Sampson et al., 1997; Reid et al., 2005; Sampson et al., 2005; Stowell and Martinez, 2007; but see Stowell and Martinez, 2009 for an attempt to identify ethnic-specific effects on crime).

Because research has not yet uncovered the mechanisms by which immigrant concentration leads to less crime in neighborhoods, what remains unproven is why this is the case. One hypothesis put forward by Sampson (2008) is that the decline in crime in recent decades in American cities is partly due to the influx of immigrants. Using time-series techniques and annual data for metropolitan areas over the 1994-2004 period, Stowell and Martinez (2009) found that violence tended to decrease as metropolitan areas experienced gains in their concentration of immigrants. Likewise, Wadsworth (2010) employed pooled cross-sectional time-series models to determine how changes in immigration influenced changes in homicide and robbery rates between 1990 and 2000. He found that cities with the largest increases in immigration between 1990 and 2000 experienced the largest decreases in homicide and robbery during that time period. Ultimately,

both of these studies concluded that growth in immigration may have been responsible, in part, for the crime drop. Still, much more research is needed to reach a definitive conclusion on the mechanisms involved in the well-documented results on the association of immigration with decreased crime rates.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

As this chapter reveals, the evidence for integration of immigrants and their descendants across various sociocultural dimensions is more positive than some fear. The beliefs of both immigrants and the second generation are converging with native-born attitudes on many important social issues. Indeed, immigrants are actually more optimistic than native-born Americans about achieving the American Dream.

Meanwhile, current research indicates that immigrants and their descendants are learning English, despite some people’s fears to the contrary.

Conclusion 7-1 Although language diversity among immigrants has increased even as Spanish has become the dominant immigrant language, the available evidence indicates that today’s immigrants are learning English at the same rate or faster than earlier immigrant waves.

Meanwhile, the potential cognitive and economic benefits of bilingualism, both among immigrants and the native-born, are just beginning to be understood and appreciated, potentially altering the debate about language acquisition in the future.

A serious cause for concern, however, is the underfunding of ESL and ELL programs:

Conclusion 7-2 Since 1990, the school-age population learning English as a second language has grown at a much faster rate than the school-age population overall. Today, nearly 5 million students in K-12 education—9 percent of all students—are English-language learners. The U.S. primary-secondary education system is not currently equipped to handle the large numbers of English-language learners, potentially stymying the integration prospects of many immigrants and their children.

Just as in the past, recent immigration has made the country’s religious landscape more diverse. However, the overwhelming majority of immigrants identify as Christian.

Conclusion 7-3 Although immigrants involved in non-Western religions, especially Islam, may confront unease and prejudice, research also shows that participation in religious organizations helps immi-

grants integrate into American society in a wide variety of ways, and immigration may in fact shore up support for religious organizations as native-born Americans’ religious affiliation and participation declines.

Crime rates are another source of concern for Americans, and the criminal propensity of immigrants is currently being widely discussed (see Chapter 1). However, popular perceptions about immigrants’ criminality are not supported by the data.

Conclusion 7-4 Far from immigration increasing crime rates, studies demonstrate that immigrants and immigration are associated inversely with crime. Immigrants are less likely than the native-born to commit crimes, and neighborhoods with greater concentrations of immigrants have much lower rates of crime and violence than comparable nonimmigrant neighborhoods. However, crime rates rise among the second and later generations, perhaps a negative consequence of adaptation to American society.

The research presented in this chapter also explores ways in which integration is a process of two-way exchange, in which immigrants and their descendants alter the social and cultural environment even as they become more like the native-born. For instance, the increases in dual immersion education programs, in which both native-born English-language speakers and immigrant LEP students learn together in two languages, and in enrollment in Spanish at the college level suggest that more native-born Americans are learning to communicate in non-English languages and may increasingly value bilingual ability. Meanwhile, immigrants are sustaining Christian religious congregations in many communities where native-born attendance has declined precipitously, even as less familiar religions such as Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism become more visible and part of mainstream discussions about religious diversity and accommodation.

Although immigrants actually commit fewer crimes that the native-born; public perceptions about immigrants’ higher potential for criminality continue to endure, spurred on by media and highly visible political actors. These inaccurate perceptions remain salient to the public because of the large number of immigrants currently residing in the United States and the rapid increase in undocumented immigration between 1990 and 2006.

Historical precedents show that religious minorities and very large groups of immigrants and their descendants were still able to successfully integrate despite their differences and the prejudices against them, in part by reshaping the American mainstream. It remains to be seen whether today’s immigrants and their children can repeat those success stories or if racial and religious differences will present more formidable barriers to integration.

REFERENCES

Abrajano, M. (2010). Are blacks and Latinos responsible for the passage of Proposition 8? Analyzing voter attitudes on California’s proposal to ban same-sex marriage in 2008. Political Research Quarterly, 63(4), 922-932.

Adesope, O.O., Lavin, T., Thompson, T., and Ungerleider, C. (2010). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the cognitive correlates of bilingualism. Review of Educational Research, 80(2), 207-245.

Akresh, I.R., Massey, D.S., and Frank, R. (2014). Beyond English proficiency: Rethinking immigrant integration. Social Science Research, 45, 200-210.

Akins, S., Rumbaut, R.G., and Stansfield, R. (2009). Immigration, economic disadvantage, and homicide: A community-level analysis of Austin, Texas. Homicide Studies, 13(3), 307-314.

Alba, R. (2005). Bilingualism Persists, But English Still Dominates. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Alba, R., and Foner, N. (2015). Strangers No More: Immigration and the Challenges of Integration in North America and Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Alba, R., Logan, J., Lutz, A., and Stults, B. (2002). Only English by the third generation? Loss and preservation of the mother tongue among the grandchildren of contemporary immigrants. Demography, 39(3), 467-484.

Alba, R., Raboteau, A., and DeWind, J. (2009). Introduction: Comparisons of migrants and their religions, past and present. In R. Alba, A. Raboteau, and J. DeWind (Eds.), Immigration and Religion in America: Comparative and Historical Perspectives (pp. 1-24). New York: New York University Press.

Alvarez, R.M., and Bedolla, L.G. (2003). The foundations of Latino voter partisanship: Evidence from the 2000 election. Journal of Politics, 65(1), 31-49.

Alvarez-Rivera, L.L., Nobles, M.R., and Lersch, K.M. (2014). Latino immigrant acculturation and crime. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(2), 315-330.

Anderson, M. (2015). A Rising Share of the U.S. Black Population Is Foreign Born. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/04/09/a-rising-share-of-the-u-s-black-population-is-foreign-born/ [July 2015].

Appel, R., and Muysken, P. (2005). Introduction: Bilingualism and language contact. In R. Appel and P. Muysken (Eds.), Language Contact and Bilingualism (pp. 1-9). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Bankston, C.L., III, and Zhou, M. (1995). Effects of minority-language literacy on the academic achievement of Vietnamese youths in New Orleans. Sociology of Education, 68(1), 1-17.

Batalova, J., and Fix, M. (2010). A profile of limited English proficient adult immigrants. Peabody Journal of Education, 85(4), 511-534.

Bean, F.D., and Tienda, M. (1987). The Hispanic Population of the United States. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Berardi, L., and Bucerius, S. (2013). Immigrants and their children: Evidence on generational differences in crime. In S. Bucerius and M. Tonry (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Ethnicity, Crime, and Immigration (pp. 551-583). New York: Oxford University Press.

Bersani, B.E. (2010). Are Immigrants Crime Prone? A Multifaceted Investigation of the Relationship between Immigration and Crime in Two Eras. Available: http://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/handle/1903/10783/Bersani_umd_0117E_11419.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [August 2015].

Bersani, B.E. (2014). An examination of first and second generation immigrant offending trajectories. Justice Quarterly, 31(2), 315-343.