Carlos Crespo, professor at Oregon Health & Science University and the Portland State University School of Public Health and vice provost for undergraduate training in biomedical research at Portland State University, moderated the workshop’s third session. He observed that today’s major health problems, such as violence, addiction, and obesity, are not necessarily medical problems, but community problems that require community solutions. The session featured four speakers who presented examples of efforts to achieve equity in community and public health approaches to preventing and treating obesity.

PROMISING APPROACHES FOR DELIVERING AND SCALING UP THE DIABETES PREVENTION PROGRAM IN UNDERSERVED COMMUNITIES

Debra Haire-Joshu, Joyce Wood professor of public health and medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, discussed promising approaches for delivering and scaling up interventions for women aged 18–39. Women are vulnerable to weight gain during the childbearing years, she explained, but often are not reached by effective interventions such as the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) because they are busy with their careers and children. “Women kind of get lost,” she argued, especially women of color who are often struggling with poverty. Despite the DPP’s proven efficacy in using lifestyle changes to help prevent or delay diabetes incidence, Haire-Joshu continued, women of childbearing age are half as likely as older

women to enroll and less likely to attend even one session (Dietz, 2017; Ritchie et al., 2017).

Haire-Joshu displayed two maps of St. Louis zip codes, one illustrating the concentration of poverty and another the concentration of the African American population. The zip codes with the highest concentrations of poverty overlap with the zip codes with the highest concentration of African Americans, she pointed out, and these areas also have a lower life expectancy (Purnell et al., 2014). These are the people who need the interventions, she asserted, but they cannot access them for a variety of reasons.

Haire-Joshu described two examples of partnerships between academia and home visiting organizations that aim to translate the DPP for women of childbearing age and to compensate for the disparities in social determinants they experience. Home visiting organizations are available, accessible, affordable, and convenient for mothers, she observed, and they address a family’s priorities and essential needs. They also reinforce ongoing support, she added, conducting family visits from the prenatal period until the last child in the home enters school. At the same time, she noted, they are usually not focused on health care and must meet criteria for reimbursement, so they represent a challenging environment for embedding a health care intervention (Ali et al., 2012; Salvy et al., 2017).

Haire-Joshu informed the audience that her group worked with Parents as Teachers (PAT), a home visiting organization with a mission to promote optimal early child development by supporting and engaging families. She explained that PAT has a standard evidence-informed curriculum and has trained nearly 4,900 parent educators across approximately 4,700 sites in all 50 U.S. states, serving more than 188,000 parents and close to 227,000 children. Almost 60 percent of participants are white, she reported, 22 percent are Hispanic, 20 percent are African American, and 5 percent are American Indian. The highest-need families receive up to 25 free home visits annually, she added, and the program is financed with state and federal funds (PAT, 2015, 2018).

Haire-Joshu said she was impressed by PAT’s national reach and local focus and delivery because of its potential to have impact outside of its immediate area. Her team trained PAT parent educators on the DPP material, which she described as an “intense” curriculum involving several months of weekly sessions, coaching, and group support. The parent educators determined how to embed the DPP material into their curriculum, she elaborated, which focused on a strength model and taught parents how to be resourceful and affirm themselves. “We did the science and they did the practice,” she said.

Haire-Joshu’s study was conducted with mothers who had overweight or obesity and also had a preschooler. The researchers compared outcomes among those receiving the standard PAT and those receiving the

PAT+HEALTH (Healthy Eating & Active Living Taught at Home) intervention. HEALTH condensed the DPP sessions into concrete behaviors around sugary beverages, portion sizes, and walking, for example, and then adapted the content for the PAT model. The parent educators had flexibility to decide when to deliver the content, Haire-Joshu observed, as they focused on family needs first, which they addressed with a family strength–oriented, solution-focused model.

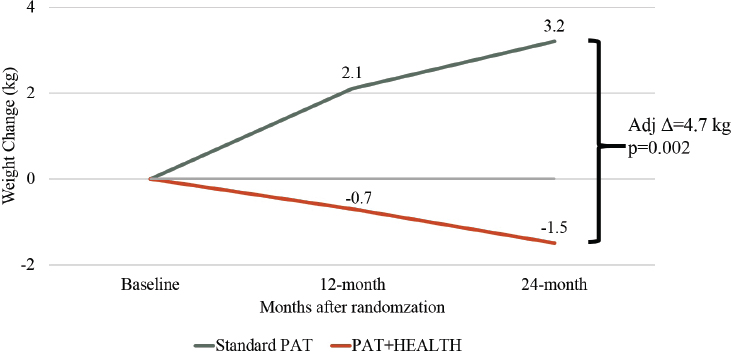

Haire-Joshu presented the results of the intervention, which she said enrolled 179 moms aged 32–33, 32 percent of whom were African American and of low income (Haire-Joshu et al., 2018). Compared with the regular PAT curriculum, she reported, PAT+HEALTH led to greater decreases in intake of added sugars from foods and beverages and greater increases in the prevalence of physical activity. She added that 26 percent of the intervention group had achieved a 5 percent weight loss—which she described as clinically significant—at the 24-month mark, compared with 11 percent of participants in the standard PAT program (Haire-Joshu et al., 2018).

Haire-Joshu highlighted a gradual decline in maternal weight over 24 months of the PAT+HEALTH intervention, compared with a gradual increase in weight during the same time period among those receiving the standard PAT curriculum (see Figure 5-1). “This was the graph that got us really excited,” she shared, because it showed that working with groups such as PAT “within their rules” and letting them address social determinants first, even though it takes longer, could make a difference. “You cannot change a behavior in an environment that is not allowing you to change the behavior,” she claimed. She described the next steps as using implementation science to bring the intervention to scale nationally and examining whether a similar impact can be achieved. She added that an effort will be made to determine what components of the dissemination and implementation approach do or do not work with a diverse sample.

Haire-Joshu’s second example was LifeMoms, a multisite, national randomized trial of weight management interventions during and postpregnancy for underserved African American women with obesity. The trial evaluated gestational weight gain and 12-month postpartum weight among 267 women, half of whom received the standard PAT and half of whom received a LifeMoms PAT+ program via 10 prenatal and 12 postpartum visits. More than half of the women were single, and nearly all of them lived in poverty, Haire-Joshu said, and she noted that half of them moved at least once and another 12 percent moved at least twice during the 4-month intervention. Clearly, stable housing was an issue, she argued, and crime rates in the neighborhoods where the women lived were above the national average (Purnell et al., 2014).

Compared with the standard PAT group, Haire-Joshu reported, the LifeMoms PAT+ group had lower gestational weight gain and smaller

SOURCES: Presented by Debra Haire-Joshu, April 1, 2019 (data from Haire-Joshu et al., 2018). Reprinted with permission.

increases in body fat and a higher prevalence of return to baseline (or lower) weight postpartum (38 percent versus 21.5 percent) (Haire-Joshu et al., 2018, 2019). She underscored that social determinants, such as stable housing and food security, were addressed first, before the intervention was implemented. Moreover, the intervention was relatively low cost and sustainable because it was fully embedded within the PAT curriculum. Haire-Joshu expressed the hope that funding would be available for LifeMoms PAT+ to be scaled nationally across a diverse group.

Haire-Joshu closed with three lessons from her research. First, non–health care organizations that address essential living conditions may offer a roadmap for promoting health equity. If the intent is to meet people where they are, she reasoned, “we need to work with the real world and organizations in the real world, which means you give up some power and control and you change how you do things, but that does not mean it cannot work.” Her second point was that long-term follow-up is needed to capture the full impact of interventions that prioritize “real-life needs” (i.e., social determinants). It takes time to put on weight and to lose weight, she maintained, remarking that the 12-month follow-up data from the interventions she reviewed were much less impressive than the longer-term data. Third, Haire-Joshu identified as a priority reaching more communities by bringing effective lifestyle interventions to scale in a way that prioritizes social determinants, noting that such health outcomes as obesity and diabetes are symptoms of those broader conditions.

BUILDING THRIVING COMMUNITIES THROUGH COMMUNITY HEALTH INITIATIVES

Pamela Schwartz, senior director for community health impact and learning at Kaiser Permanente, discussed that organization’s Community Health Initiative, a multisector community-based obesity prevention intervention. Implemented in 2004, the Community Health Initiative operated in more than 60 communities nationwide, she reported, serving 715,000 residents and 209,000 school-age youth. The interventions target the entire geography where they are implemented, she explained, rather than focusing on a single racial or ethnic group.

According to Schwartz, evidence was sparse when the initiative was designed. In the absence of clear evidence, she explained, Kaiser Permanente’s equity lens was to choose the most vulnerable communities and engage them in the design, implementation, and evaluation of the initiative. Early on, she continued, transformation occurred in these communities and their physical environments. But she added that for the initiative to achieve its goal of advancing population health, Kaiser Permanente recognized that “dose” was important, elaborating that many lives had to be touched significantly enough to make a difference.

Schwartz asserted that the concept of “dose,” which Kaiser Permanente described as reach multiplied by strength, was a valuable contribution to the field. In addition to touching many lives, she said, the touch must be strong, which may mean multiple times, multiple days, or multiple interventions targeting the same population. She described examples of “dose” for healthy eating and active living in a school setting, explaining how small changes led to larger, school-wide reforms and eventually changes in the surrounding community settings. She highlighted the importance of having meaningful conversations with community partners to build interventions with the best potential for impact. She also underscored the initiative’s community-driven approach, which she said sometimes required focusing initially on pressing community issues, such as violence or economic security, before undertaking efforts related more directly to obesity prevention. She acknowledged that some struggle was involved in determining how to remain community-driven while also fulfilling the charge of advancing population health in the context of an obesity prevention intervention.

Schwartz explained how the initiative’s evaluation strategy evolved as community feedback revealed that the initial evaluation methods were not capturing all of the intervention’s impact in the community. As an example, she described the introduction of a new methodology for photo voice, which gave residents the opportunity to capture descriptive impact data while advocating for additional changes that could be made. In addition, community members were surveyed about the changes they wanted to see.

According to Schwartz, community-level surveys of population health often do not collect such information about what matters to communities.

Schwartz then highlighted examples of community impact, such as a 7 percent increase in students walking or biking to school in a Colorado community, an increase that was sustained 3 years later, and increases in vegetable consumption and decreases in soda and fried food consumption among church congregations in a California community. She identified as a common theme in the communities that experienced the greatest population health impact that they experienced a combined dose of policy, systems, and environmental change that affected a single outcome, such as physical activity, and “saturated” a single population, such as schoolchildren. As an example of outcomes, she cited two California cities in which the intervention was associated with a significant increase in the percentage of children in the “healthy fitness zone” for aerobic capacity.

Schwartz outlined six key takeaways from the Community Health Initiative. First, she said, community engagement and capacity building are vital, but difficult to do well and authentically. She added that it is important to build capacity for a specific outcome that is connected to the rest of the intervention. Second, schools were the most promising setting for achieving changes in long-term behavior, which she said may have been in part because the captive audience increased reach and strength. Population-level results were not observed in community settings, she reported. Third, the most promising strategies were related to physical activity. Fourth, Schwartz reported that the strategies with the most mixed results were those involving corner stores, school gardens, and health-promoting media campaigns in isolation. These results prompted conversations within Kaiser Permanente and with the communities, she recalled, about which interventions have the most potential to impact population health. Fifth, she pointed out that changes take time, and more improvements were observed in the longest-running community sites. Lastly, she reiterated that dose matters, calling for a combination of coordinated, mutually reinforcing strategies.

Schwartz then shifted to discuss Kaiser Permanente’s Community Health Strategic Framework, which she called an “ambitious,” equity-centered strategy that aims to assess and improve the health of Kaiser Permanente’s communities. There is some tension, she acknowledged, in trying to determine how to achieve scale, impact, and equity simultaneously. An integral part of that objective, she continued, is to create and use an equity index to determine a community’s average level of opportunity to be as healthy as possible, as well as the inequality or variability in opportunity within the community’s geography. Schwartz explained that the “opportunity index” is derived from the neighborhood deprivation index and accounts for social determinants of health, including income, education, employment, and housing (Messer et al., 2006). The index is already

yielding insights, she reported, despite its nascence. For example, areas where there is variability in opportunity are flagged as potential sites to which to direct resources.

Schwartz added that Kaiser Permanente is also working to apply an equity lens in its grantmaking and community health needs assessments. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act required all nonprofit hospitals to conduct periodic community health needs assessments, she observed, and then create a plan addressing the identified health needs. She reiterated that community voices are critical in developing strategies that address local needs. Finally, she recapped Kaiser Permanente’s efforts to publish and share its lessons learned about community health strategies to enrich the field and inform other stakeholders. Much has been learned, she said in conclusion, but there is much more to learn.

APPROACHES IN NATIVE AMERICAN COMMUNITIES

Valarie Blue Bird Jernigan (whose first presentation is summarized in Chapter 3) returned to discuss the THRIVE (Tribal Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments) study, an environmental intervention to improve tribal food environments in Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations in rural Oklahoma. Obesity, diabetes, and hypertension were highly prevalent among those two tribal nations, she explained, and people who were food insecure had a higher prevalence of those three conditions even after adjustment for sociodemographic factors. Nearly 60 percent of citizens in the two tribal nations reported shopping for food three or more times per week at tribal convenience stores, she continued, which influenced her team’s decision to design an intervention to implement what she termed “healthy makeovers” in convenience stores in Chickasaw and Choctaw nations (Jernigan et al., 2019). According to Jernigan, these convenience stores differ markedly from the corner stores often found in urban environments. Convenience stores, she explained, are in very rural areas and not only sell packaged and hot foods but also have smoke shops, miniature casinos, and spaces where community members can sit and chat over a cup of coffee or even gather for birthday parties.

To guide the intervention, the research team used what Jernigan said was one of the few published conceptual models presenting food security as part of the larger food system (Rutten et al., 2011). This model, she observed, helped the team map the food system and understand the environmental, social, economic, and human factors that contributed to food insecurity and some of the health outcomes of interest.

Jernigan described the study design as a cluster controlled trial including eight stores, with two stores per tribe assigned to implement the intervention and two stores per tribe assigned as controls. As a longitudinal

cohort study, she continued, it involved surveying 1,637 native shoppers before and after the intervention. Jernigan reported that the primary outcomes were store-level changes in the availability of fruits and vegetables, as measured by sales data, store inventory, and nutrition environment measures adapted for tribal stores, and individual-level changes in perceived food environments and intake of fruits and vegetables, as measured by self-report questionnaires (Wetherill et al., 2018).

Jernigan explained that the intervention strategies were tailored for native stores and guided by recommendations from an Institute of Medicine report (IOM, 2005), and included changes to the stores’ products, placement, promotion, and pricing to improve the food environment. Phase one was dedicated to assessing the current food options and establishing baseline nutrition environment scores for the stores. Jernigan added that nutrition analysis was performed for currently available foods as well as for foods that were potentially available from vendors, and the tribes had an opportunity to establish criteria for healthier foods. They settled on 10 new snack options of ≤250 calories and 5 new meal options of ≤500 calories, with ≤30 percent of calories from fat, she elaborated, and some stores had to undertake remodeling to accommodate bulk produce orders for the intervention foods.

Jernigan then described how the team conducted focus groups with convenience store workers and shoppers to gather input on placement, pricing, and promotion strategies. Jernigan characterized the plan to modify the store layout so that the intervention foods were placed prominently throughout high-traffic areas and labeled in tribal language as a “better choice.” Some intervention foods had special discount pricing, she added, while others maintained the standard suggested retail price and never needed to be discounted because they sold out every week.

Next, Jernigan described the study’s statistical methods and results. She reported that, compared with the control stores, THRIVE improved objective and perceived measures of tribal food environments. It also resulted in widespread changes to the types of foods offered by vendors in both tribal nations, she added, which increased the variety and availability of fruits and vegetables in all other tribal programs served by those vendors. She noted that the intervention led to changes in shoppers’ purchasing behaviors, but changes to fruit and vegetable intake were not observed. Jernigan speculated that this result may be attributable to limitations in the study’s dietary assessment tool or to the study’s singular focus on changes to one environment rather than larger community-wide changes. Furthermore, she elaborated, the study did not focus on individual-level change. She reported that greater frequency of shopping at an intervention store tended to be associated with a greater likelihood of noticing the intervention food displays and signage and of purchasing fruits and vegetables (Jernigan et al., 2019).

Jernigan reflected that a key benefit from the intervention was the gradual recognition that health belongs in all sectors of tribal nations, not just its clinical settings. She highlighted the study’s investment in partnering with the business sectors of tribes to agree on a process that would achieve “win-wins” and align business, environmental, and health agendas. To illustrate, she explained that the researchers agreed to share certain study data with the tribal governments, which motivated governments’ participation in the trial, and that stores agreed to share sales data with researchers in exchange for help with health impact assessments. In closing, Jernigan emphasized that the study’s message was to advance health in all policies and health for future generations.

CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE OBESITY AND DIABETES INTERVENTION RESEARCH IN NATIVE HAWAIIANS

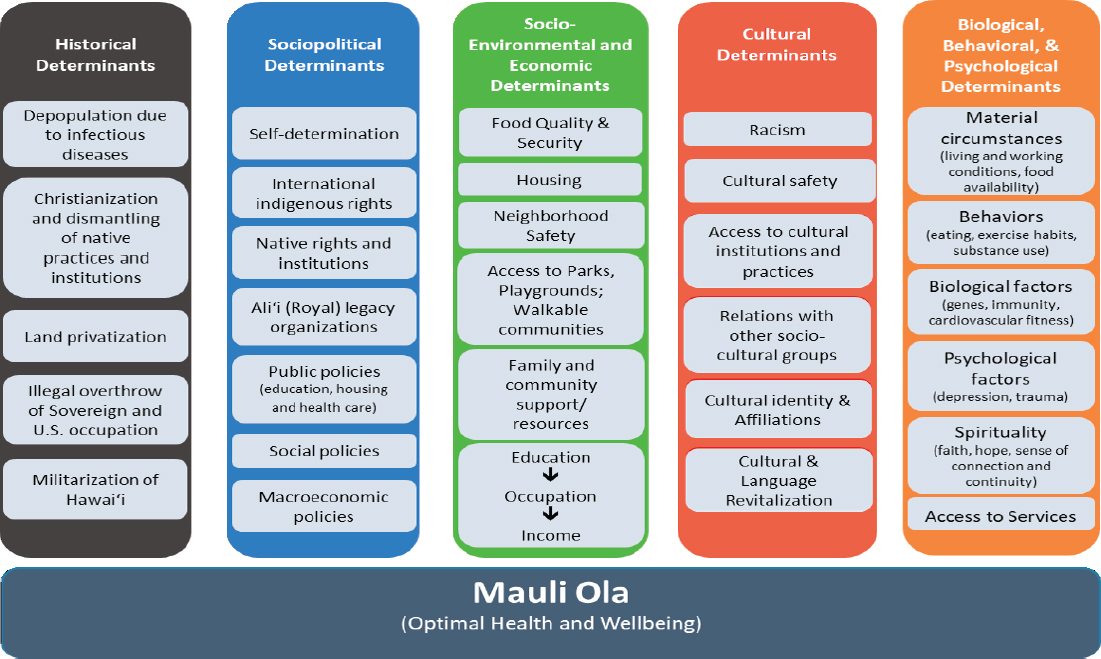

Joseph Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, professor and chair of Native Hawaiian health in the John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii at Mānoa, discussed culturally responsive obesity and diabetes intervention research in Native Hawaiians. He opened his presentation by reviewing social and cultural determinants of Native Hawaiian health (see Figure 5-2). After briefly reminding participants of the historical trauma experienced by indigenous people, he highlighted the importance of cultural determinants of health for indigenous populations, adding that many native people believe a return to traditional values and practices is a solution to addressing health inequities.

Kaholokula went on to observe that most interventions in Hawaii and the greater Pacific focus on biological, behavioral, and psychological determinants of health, and are unrealistic and irrelevant to many Hawaiians because they neglect other determinants of health, such as historical, cultural, and sociopolitical (Kaholokula, 2017). The interventions tend to be intense, he continued, based on ideals rather than the reality of the people, and programs are not sustainable across settings or easily accessible to those at risk. Hawaii’s high cost of living means that many residents work two jobs, Kaholokula added, often shift-type work that does not maintain a regular schedule.

Kaholokula outlined several factors associated with obesity and diabetes among Native Hawaiians. These people are more likely to live in environments with fast-food outlets and poor facilities for physical activity, he observed, and have relatively higher calorie intakes and lower levels of income and physical activity (Kim et al., 2008; Mau et al., 2008; Uchima et al., 2019). He highlighted that Native Hawaiians who report high levels of overt racial discrimination compared with those who do not are three times as likely to have overweight or obesity (McCubbin and Antonio, 2012).

SOURCES: Presented by Joseph Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, April 1, 2019. Adapted from Kaholokula, 2017. Reprinted with permission from University of Hawaii Press.

Kaholokula then described the two types of culturally responsive approaches that have addressed obesity and its related health inequities in Hawaii. He explained that the first type, cultural adaptation (also known as tailoring), preserves core elements of an evidence-based intervention and incorporates culturally relevant elements for a new population. The adaptation takes two forms, he elaborated: surface structure changes, such as a change in program name or incorporation of local customs regarding food and physical activity; and deep structure change, such as incorporating a particular group’s worldviews, values, and practices into the intervention’s core elements. The other type of culturally responsive approach, Kaholokula continued, is cultural grounded (also known as ground-up), which uses the target population’s sociocultural context and worldviews as a foundation for program elements (Kaholokula et al., 2018). He went on to describe three programs that use cultural adaptation or cultural grounded approaches.

Kaholokula first described the Partnership for Improving Lifestyle Intervention (PILI) Ohana lifestyle program, which was adapted from the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) (mentioned earlier in the session by Haire-Joshu) and tailored to Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. PILI in Hawaiian means to come together or cling to, he translated, and Ohana means family, both immediate and extended; therefore, the program’s name represents its approach of gathering communities and families together to address health inequities.

Together with community partners, Kaholokula’s research team began by examining intrapersonal, interpersonal, and community-level factors that influence Native Hawaiians’ ability to make and maintain healthy lifestyle choices. Through qualitative research, he elaborated, such contributing factors as cultural stereotypes and access to culturally relevant activities and affordable healthy foods became apparent (Kaholokula et al., 2018). He added that Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are faced with numerous stereotypes from the mainstream, such as that they are supposed to be big genetically.

Kaholokula went on to explain that the program condensed the DPP’s 16 lessons into 8, and added two new topics that were important to communities—eating healthfully within a budget and communicating effectively with one’s physician—while retaining the core curriculum. He described surface structure modifications that included use of words, terms, and food examples specific to Native Hawaiian communities, and deep structure modifications that included delivering the DPP curriculum in groups (instead of individually) to capitalize on social support and role modeling.

Kaholokula explained further that community peer educators trained in behavioral change and motivational interviewing techniques delivered the program’s curriculum to groups of 10–12 participants over 3 months.

The educators were a cultural component of the intervention, he pointed out, because as community members themselves, they understood the culture, community context, and assets that could be leveraged for health promotion. A 6-month weight loss maintenance phase followed the DPP curriculum, he added, in which participants were randomized to receive a standard behavioral program consisting of phone check-ins and review of educational materials or a culturally tailored family and community intervention. In the latter case, he elaborated, participants were asked to engage their families to support or join them in practicing healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Presenting results from the 3-month DPP component of the program, Kaholokula said that several Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander cohorts who received the curriculum experienced, on average, significant yet modest weight reduction; improvements in blood pressure, physical function (measured by the 6-minute walk test), and self-reported physical activity levels; and decreased intake of dietary fat (Kaholokula et al., 2013b; Mau et al., 2010; Townsend et al., 2016). Compared with participants in the standard behavioral program, he continued, participants in the PILI Ohana group (which received the family and community weight loss maintenance intervention) were more likely to have achieved clinically significant weight loss after the full 9 months of the program, and by the 3- to 6-month follow-up, were less likely to have regained weight (Kaholokula et al., 2012, 2013a).

Kaholokula then transitioned to summarize a similar culturally adapted approach to diabetes self-care called Partners in Care. This program had a unique cultural adaptation technique, he explained, as it incorporated a Hawaiian “talk story” approach that allowed the peer educators to use metaphors to link participants’ situations to effective self-management behaviors. Local characters were depicted at each lesson to reinforce traditions of families working together and to help facilitate communication and storytelling among group participants. After 3 months, Kaholokula reported, participants had achieved significant reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels (Sinclair et al., 2012).

Next, Kaholokula briefly mentioned a culturally grounded approach using hula, the traditional dance of Hawaii, to address hypertension self-management in Native Hawaiians. Participants in the hula-based study, which he said also included modest self-care, educational materials, and hypertension management counseling, were more likely to improve their blood pressure 3 months postintervention compared with participants in a control group. They also reported improvements in social functioning and body pain associated with improvements in blood pressure. Kaholokula added that from a cultural standpoint, another important result was that the hula intervention group reported significant reductions in perceived racism (Kaholokula et al., 2017). Based on these results, he argued, a culturally

grounded approach can have clinical, psychosocial, and sociocultural benefits, which he said are not often observed in other types of mainstream interventions.

Kaholokula summarized additional lessons learned from his research: peer educators’ commitment and community knowledge are more important than their education level or disciplinary background; health outcomes may differ as a result of ethnic group differences in acculturation-related factors, motivation, and community resources; greater participant engagement appears to enhance weight loss; greater initial weight loss leads to greater long-term weight loss, so another strategy, such as a cultural empowerment model, may be needed for those who do not lose weight early on; and obesity prevention is to be prioritized because weight loss is difficult once a person has obesity.

DISCUSSION

A brief discussion period followed the third session of the workshop. Topics included engaging nonhealth sectors and reviving native people’s traditional practices despite modern forces that drive acculturation.

Engaging Nonhealth Sectors

A participant asked Haire-Joshu and Schwartz how to engage and partner with nonhealth sectors. Schwartz responded that her organization, Kaiser Permanente, gained a seat at the table through its role as a funder, but it also worked with communities as a partner. There was regular discussion with the communities about intervention strategies, she elaborated, and local evaluators worked in communities on an ongoing basis. Haire-Joshu recalled that she first heard about PAT from her colleagues with young children. Recognizing that the organization’s curriculum did not include nutrition, she reached out to gauge its interest in child nutrition and parent modeling of nutrition. That outreach led to what has been a long-term relationship supported by numerous grants, Haire-Joshu recounted, which have been used to explore a variety of aspects of parental modeling to children, different health behaviors, and lifestyle change strategies. She stressed that flexible approaches are important for such partnerships because organizations change over time as their missions and models evolve and their leadership changes.

Acculturation and Traditional Practices

Jernigan and Kaholokula were asked how their teams were able to engage native communities with their traditional values and counteract the

market forces that unfavorably impact native people’s healthy ways of living. Jernigan replied that traditional foods and food practices are prioritized in some native communities, while others prioritize convenience and low cost. Nonetheless, she observed that people genuinely desire to learn about their traditional cultural practices. It is always about the larger story, she said, emphasizing the value of framing interventions within the broader picture of native identity, healing, and oneness with the community and traditional practices. This perspective tends to bring people into interventions that they might have avoided if the framing were about obesity, she explained, adding that they are more likely to join a discussion about food sovereignty.

Kaholokula underscored the importance of changing the narrative for indigenous people. For example, when Captain James Cook first arrived in Hawaii in 1770, he and his officers observed a healthy, robust indigenous population. But since then, Kaholokula continued, false stereotypes that have emerged from society and even from the health care profession have become internalized among native people. Furthermore, he added, the economic situation has driven them to adopt certain Western lifestyles, such as fast food and processed foods. He explained that a cultural empowerment approach is attempting to shift the narrative so that native people understand their healthy, proud roots and reclaim their traditional practices as they shed negative stereotypes.

This page intentionally left blank.