5

Alternative Perspectives for Research

As discussed in Chapter 4, given the conceptual and methodological limitations entailed in separating out variations among individuals due to effects of age, generation (birth cohort), or social change (period), there is currently no strong empirical evidence for shared differences that would distinguish one whole generation from another. Chapter 4 describes these limitations and calls for improved attention to methods used, internal and external validity, and the conclusions that can appropriately be drawn from any findings in future research examining age-related, period-related, or cohort-related differences in workforce attitudes and behaviors.

Despite the lack of scientific evidence for generational differences, an interesting reality is that people tend to believe these differences exist, a belief that sustains perceptions of many differences among workers (Lester et al., 2012; North and Shakeri, 2019). Therefore, it could be more fruitful for future research to focus on examining beliefs and perceptions about the qualities possessed by generations and their impacts in the workplace (Costanza and Finkelstein, 2017; Weiss and Perry, 2020), keeping in mind that these beliefs and perceptions may not reflect true attributes of any birth cohorts and thus can be studied as generational stereotypes and biases (Perry et al., 2017). For example, it is important to understand how beliefs and perceptions about generational attributes develop. Research could examine how individuals develop beliefs and perceptions about their own birth cohort, as well as about the generations/birth cohorts of others. It is also important to understand how beliefs and perceptions about generations impact behaviors and interactions in the workplace. Indeed, if

those impacts occur mainly through stereotypes and biases, understanding of these impacts can have significant implications for managing workers fairly.

To help inform future research, this chapter examines (1) the inherent appeal of and major psychological motivations for using generational ascriptions, (2) the risks of using those ascriptions in the workplace, and (3) additional perspectives on the multiple influences on workforce development over time.

THE INHERENT APPEAL OF GENERATIONS

The idea of the younger generation’s being different from the older generation is an idea that goes back thousands of years. Observations made about the new generation of youth and young adults are strikingly similar throughout the ages, with the older generation complaining that individuals in the younger generation have poor morals; are degrading the language; and are lazy, thoughtless, and selfish (see Box 5-1). Thus, the idea that the steady flow of new humans can be cleaved into groups that are distinctly different from one another is not new, nor is the conflict between one generation and another. Nonetheless, the notion that each generation is decidedly less motivated or capable than the one before is not supported by either common sense or empirical evidence. If the observations about young people made repeatedly over time were true, societies would have quickly devolved instead of making steady progress in business, public health, and other areas.

Negative attitudes toward older adults have persisted for some time, with older adults often being portrayed as out of touch or incompetent. For example, in 2019, the phrase “OK boomer” exploded across social media and even spread as far as the New Zealand Parliament (Mezzofiore, 2019) and the U.S. Supreme Court (Liptak, 2020). This phrase encapsulates young people’s anger at the hand they feel they have been dealt—including climate change, rising inequality, and student debt—by older generations and conveys the sentiment that older people “just don’t get it.” Young people use the phrase as a retort to older people who “don’t like change,” “don’t understand new things,” and “don’t understand equality” (Lorenz, 2019).

Reasons for the current pervasiveness of the concept of generations, their labels, and assumed differences among them may be that they have become strongly socially constructed over time and have emerged to serve a purpose in social identities (Rudolph and Zacher, 2015, 2017). Humans are naturally inclined to categorize and generalize, skills that are useful in deciding quickly whether a situation is dangerous or simplifying a mass of information that one needs to process (Rosch, 1978). Social categorization is

a cognitive process by which individuals place other people and themselves into social groups (Allport, 1954/1979; Fiske and Taylor, 1991). This categorization can be influenced by various sociocontextual elements, including existing labels and definitions (Brewer and Feinstein, 1999; Fiske 1998). Social categorization is common for observable characteristics, such as when people encounter, and draw quick inferences about, individuals of a certain race, gender, linguistic group, or age (Liberman, Woodward, and Kinzler, 2017). Often linked to impressions of age, generational categories provide a way to quickly stereotype other people’s values, skills, and tendencies based on ideas about their generation as a whole (Costanza and Finkelstein, 2015).

The existing literature on the formation of beliefs and perceptions about generations is limited. Some research has shown that as people grow older, they develop a more positive view of their birth cohort as compared with their age group (Weiss and Lang, 2009). One explanation is that in contrast to age identity, which is often perceived as threatening, generation identity represents a resource in later adulthood that provides a sense of agency, positive self-regard, and continuity (Weiss and Lang, 2012). Supporting this explanation, Weiss and Perry (2020) show that generational metastereotypes compared with age metastereotypes (i.e., what people think other people believe about their generation or age group, respectively) positively influence older adults’ work-related self-concept. This line of research attempts to explain how people develop beliefs and perceptions about their own generation/birth cohort, while other research is focused on understanding how people develop beliefs and perceptions about others’ generations/birth cohorts.

Protzco and Schooler (2019) attempted to study systematically whether and why people believe that today’s youth are deficient relative to previous generations. They asked the study participants to rate the children of today against the children of their own generation on a variety of traits. The researchers also assessed the participants themselves on those same traits, including respect for authority, intelligence, and enjoyment of reading. They found that people who excelled on a particular trait in question were more likely to believe that children are in decline on that same trait. Compared with participants who do not like to read, for example, participants who like to read were more likely to believe that children these days like to read less compared with children when the participants were young. The researchers theorized that denigrating today’s youth is a fundamental illusion grounded in several cognitive mechanisms, including a bias toward seeing others as lacking in traits in which one excels and a memory bias that projects one’s current traits onto past generations. To denote this phenomenon, Protzco and Schooler coined the term the “kids these days effect,” noting that

complaints about “kids these days” have been pervasive through millennia of human existence.

RISKS OF USING GENERATIONAL CATEGORIES

Generational categories have taken on a life of their own (see Chapter 3). The labels used to describe people can shape the way they are perceived, regardless of whether those labels are accurate (Darley and Gross, 1983). While social categorization can be useful in some instances, it can also lead to prejudice, bias, and inappropriate stereotyping (Liberman, Woodward, and Kinzler, 2017). In this way, categorizing and labeling people—whether on the basis of generation, race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or some other characteristic—can be dangerous and harmful. In the present context, the use of one label for everyone born within a particular time period can lead to stereotyping with generalities that may or may not be true for particular individuals. People born in the same year or span of years may have very different experiences, depending on such factors as socioeconomic status, geographic location, education level, gender, and race. These factors modify how people experience events that are supposedly formative for their generation. For example, people who came of age during the time of the civil rights movement likely had very different experiences depending on their race and the region of the country in which they lived. Even generational labels themselves can be exclusionary and ignore the heterogeneity within generations. For example, Erica Williams Simon notes that calling the youngest generation iGen (in reference to the iPhone) would “exclude a lot of people” who lack the access to technology of higher-income people. She argues that it is “very hard to label something in a way that reflects everyone’s experience” (Raphelson, 2014).

Labels that start out benign often can become pejorative over time as people emphasize their negative over their positive connotations. The Wall Street Journal (2017) published a note on its style blog suggesting that the term millennials had become “snide shorthand” in the paper, and observing that millennials span a wide age range and that some are leaders and shapers of society. The note asserts that many of the habits attributed to millennials are actually just common among young people in general, and that if journalists are simply referring to young people, they should “probably should just say that.”

In the workplace, some studies show that people’s stereotypes about different age or generation groups, or their perceptions of such stereotypes, can influence how they perform and how they interact with others, as well as drive intergenerational conflict in the workplace (Urick et al., 2017). One survey found that older and younger workers thought others viewed them more negatively than they actually did; for example, older people thought

others might stereotype them as “boring” and “stubborn,” whereas people actually believed older workers were “responsible” and “hard-working” (Finkelstein, Ryan, and King, 2013). Another study found that when workers believed other people held negative stereotypes about their age group, they responded either by becoming anxious and worried about how to perform, or by becoming indignant and challenging themselves to defy the stereotype (which could result in negative or positive actions) (Finkelstein et al., 2020). In a qualitative study, Urick and colleagues (2017) used interview data to identify a variety of possible tensions between younger and older workers stemming from perceptions of generation-based differences in values, behaviors, and identities. Based on these findings, it appears that interventions designed to deal with intergenerational issues at work can be more successful if they lead workers to see more similarities across generational groups (Costanza and Finkelstein, 2017). (Workforce management is discussed further in Chapter 6.)

PERSPECTIVES TO ADVANCE RESEARCH

In the absence of a compelling alternative to a generational mindset in decision making, people will likely continue to use generational heuristics to make decisions even if doing so ultimately has null, negative, or unintended consequences leading to workplace discrimination (Costanza and Finkelstein, 2015). It appears that, intuitively, people are inclined to agree with early sociological formulations according to which events that co-occur with developmentally critical periods (e.g., late adolescence/early adulthood) will influence attitudes and values in a significant way. Although compelling, however, generational paradigms tend to ignore the diversity of behavior, attitudes, and values within a generational group. Specific events occurring during critical periods of development may shape attitudes and values, but these effects appear to be influenced by life events and idiosyncratic experiences related to one’s social class, geographic location, and other factors (Baltes, Reese, and Lipsitt, 1980).

The task for researchers is to identify alternatives to current theory and research on generations that are better at exploring the ways in which people’s experiences—both shared and individual—may affect their work-related attitudes and behaviors. Described below are three perspectives that can be taken in thinking about the variations among workers: lifespan development theories, changes in the work context, and the aging workforce. These are not the only perspectives that may guide future research—the committee recognizes that further study and theory development may produce perspectives of better value for understanding workforce issues—but these three perspectives have existing scientific literature upon which to build.

Lifespan Development Theories

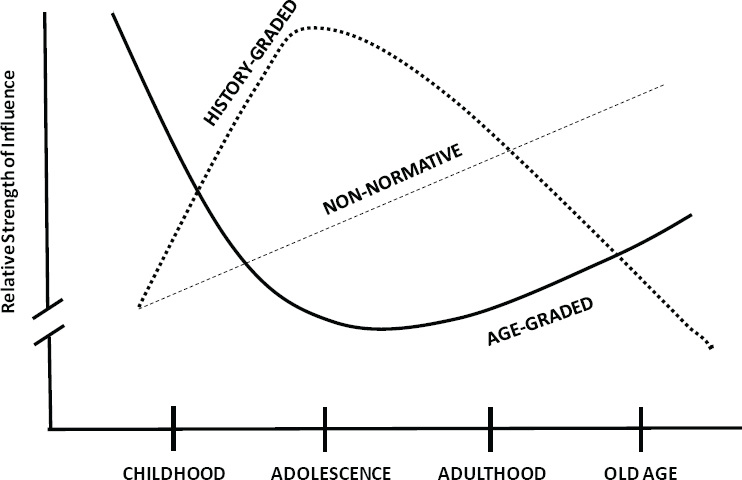

Like the sociological theories and popular generational ideas described in Chapter 3, Baltes and colleagues’ lifespan development formulation considers individual characteristics and sociocultural influences on human development (Baltes, Reese, and Lipsitt, 1980). Several other scholars have also taken a lifespan approach to understanding individual development (e.g., Durham, 1991; Lerner, 2002; Li, 2003; Magnusson, 1996). Lifespan development theories differ from generational ideas in that they do not presume generational categories (Rudolph and Zacher, 2017). Rather, lifespan development theories posit three influences on identity formation—biological and environmental determinants—that provide a lens through which people interpret their experiences:

- Normative age-graded (ontogenic) influences. These are defined as “biological and environmental determinants that have…a fairly strong relationship with chronological age” (Baltes, Reese, and Lipsitt, 1980, p. 75). They also include sociocultural events that happen around the same age (e.g., education, marriage, parenthood).

- Normative history-graded (evolutionary) influences. These environmental and biological determinants are associated with historical time. They include significant events (e.g., war) and sociocultural phenomena (e.g., social media) that are normative in that they affect everyone who experiences them.

- Non-normative life events. These biological and environmental determinants are idiosyncratic to individuals. Examples are person-specific personality traits and abilities, knowledge acquired through individual experiences, individual illnesses that may cause an impairment, and opportunities influenced by a person’s family station and socioeconomic status.

Lifespan development theories posit that each of these influences has a different trajectory (Baltes, Reese, and Lipsitt, 1980); see Figure 5-1. Normative age-graded influences have a greater effect in early and late developmental periods, when people purportedly have less agency, and can be represented with a u-shaped curve. Normative historical events have a greater effect during critical developmental periods (e.g., late adolescence/early adulthood) and can be represented with an inverted u-shaped curve. And the influence of non-normative life events becomes increasingly important through the life span and can be represented by a line with a positive slope.

NOTE: The interaction among the systems of influence is shown as linear and additive, but a transactional representation may turn out to be more useful.

SOURCE: Baltes, Reese, and Lipsitt, 1980; Figure 3. (Reprinted with permission.)

Lifespan development theories consider the impact of historical events on human development but also stress the importance of biological or cultural factors (e.g., social class, urban/rural status) in explaining the differences among people. This allowance for variance in the effects of historical events thus weakens the idea of generational membership based on normative historical events. Because the lifespan development perspective encompasses a broad range of factors that may influence a person’s development, it is not a testable theory per se, but rather a paradigmatic framework (Baltes, Reese, and Lipsitt, 1980; Rudolph and Zacher, 2017). Moreover, although there has been much research on the effects of non-normative life events and individual differences on development, job performance, and motivation (Kanfer and Ackerman, 2004; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018; Schmidt and Hunter, 1998), no research has endeavored to examine all three of the above trajectories in lifespan development theories simultaneously.

Changes in Work Context

As discussed in Chapter 2, the world of work and the composition of the workforce are different from what they were in years past. These changes in the context of work, together with changes in the social context, have likely influenced the average person’s attitudes, personality, values, and behaviors regardless of that person’s age or generation. Thus, it is possible that as observers have witnessed changes in people’s attitudes and behaviors, they have misattributed these changes to generations.

As noted in Chapter 4, when sophisticated methods are used to study differences among people, the observed differences are found to be related more strongly to period effects, indicating gradual change over time in the general population, than to generation effects, which would indicate change limited to a subgroup of the population based on birth year. Thus, the focus on generational issues misattributes actual changes in workplace context to changes in the preferences of workers from different generations. For instance, some have argued that younger generations prefer team-based work (Deal and Levinson, 2016); however, studies on this topic have showed that the personal preference for team-based work has actually decreased over time (Twenge et al., 2010). On the other hand, there is substantial evidence that work has become more interdependent and that teams are more prevalent in today’s organizations (Wegman et al., 2018). Accordingly, future research is needed to identify and examine changes in contextual demands that impact the average worker (regardless of age or generation), instead of focusing predominantly on identifying differences in the work-related values of different generations of workers.

The Aging Workforce

Focusing on generational issues also has masked real challenges in the management of a more age-diverse workforce. New workplace norms, practices, and behaviors likely are developing as a function of changes in workforce demographics.1 There is a large body of literature on “older” workers, and research attention to the aging workforce has increased as the percentage of workers over age 55 has continued to grow (Baltes, Rudolph, and Zacher, 2018; Fraccaroli and Truxillo, 2011; Hedge and Borman, 2012; Truxillo, Cadiz, and Hammer, 2015). This research has tended to focus on cognitive and physical changes as workers age and discrimination toward older workers (Hedge and Borman, 2012; Parry and McCarthy,

___________________

1 Another National Academies study is reviewing the literature on the aging workforce in the United States. The study report, due in Spring 2021, will examine factors associated with decisions to continue working at older ages and the social and structural factors, including workplace policies and conditions, that inhibit or enable employment among older workers.

2017; Wang, Olson, and Shultz, 2013). Little research has focused on age diversity in the workplace compared with diversity issues around gender, race, and ethnicity, but there is growing interest in studying age as a dimension of diversity in the workplace and on work teams (Finkelstein et al., 2015; Truxillo, Cadiz, and Hammer, 2015).

In research to date on “older” workers, chronological age has been used as a primary measure in attempting to predict such organizational outcomes as individual performance, workplace discrimination, and benefits of age diversity. However, there is little agreement in the literature on what defines an older worker, and this literature has found considerable variation among older workers with regard to such attributes as cognitive functioning, future orientation, and personality (Bal et al., 2010; Mühlig-Versen, Bowen, and Staudinger, 2012; Nelson and Dannefer, 1992). This variation reflects the fact that the experience of aging is different for different people, and that aspects of work linked to older workers (e.g., retirement) vary across work contexts and cultures (Truxillo, Cadiz, and Hammer, 2015). Moreover, the research has yielded a number of contradictory or null findings. For example, if job performance does not decline with age, why does age discrimination persist? and Why is age diversity not linked consistently to productive outcomes? (North, 2019).

Research has shown that chronological age alone is not a sufficient predictor of organizational outcomes (Ng and Feldman, 2008). Potential paths forward for future research could entail considering the multidimensionality of age: to examine other work-related attributes in conjunction with chronological age, such as one’s organizational tenure (Ng and Feldman, 2010a) and accumulated job experience and to consider the “age culture” of one’s workplace. It may even be possible to consider the impact of generational perceptions in the workplace in conjunction with these other factors; that is, when workers consider themselves to be part of a generation, this perception may influence their work identity and attitudes (North, 2019).

SUMMARY

The goal of this chapter has been to explain that, while appealing, generational thinking has its risks and limitations when used to inform workforce management and employment practices. However, the persistence of generational stereotypes and biases can potentially create tensions in the workplace and impact employee decisions.

Research assessing the effects of generational biases in the workplace and advancing theories on their influences on workforce behavior continues to be worthwhile. Lifespan development perspectives might present a more adaptive path forward for exploring variation in individuals’ work--

related attitudes and behaviors than reliance on generational paradigms. Individual workers are constantly interacting with their environments, and these interactions can alter their work-related attitudes and behaviors in important ways.

A growing body of research is focused on managing workers with different needs and capabilities (e.g., considering flexibility in training opportunities). Another important line of inquiry is aimed at understanding the management approaches of effective organizations. Some of this work is discussed in Chapter 6. Overall, recent research has underscored the importance of work context and of the variations in needs among workers regardless of age or generation. Future research designed to inform workforce management needs to take an integrative approach, recognizing the importance of work context, shared influences, and individual trajectories.

Recommendation 5-1: Researchers interested in examining relationships between work-related values and attitudes and subsequent behaviors and interactions in the workplace should endeavor to identify and better understand alternative explanations for observed outcomes that supplement explanations associated with generations. This effort would include attention to generational stereotypes and biases that might exist among workers. Research should also seek to better understand the multiple factors that influence attributes of individual workers, including aging in the workplace, and the changes in the work context that affect the behaviors of all workers.

This page intentionally left blank.