4

People: Research and Lessons from Addressing Specific Populations’ Health Literacy Needs

The second panel of the workshop was moderated by Marina Arvanitis, assistant professor of medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Arvanitis introduced the panelists: Deena Chisolm, professor of pediatrics and public health at The Ohio State University, director of the Center for Innovation in Pediatric Practice, and vice president for health services research in the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital; Gail Nunlee-Bland, professor of pediatrics in medicine at the Howard University College of Medicine and chief of endocrinology and director of the Diabetes Treatment Center at Howard University Hospital; and Steven Hoffman, assistant professor at the Brigham Young University School of Social Work.

The panel was charged with exploring research and lessons learned from addressing specific populations’ health literacy needs.

HEALTH LITERACY FOR YOUTH WITH SPECIAL HEALTH CARE NEEDS

Deena Chisolm, The Ohio State University

“Adolescents with special health care needs” (SHCN) refers to a broad concept that includes any teen who has more interaction with the health care system than their average peer. For example, this includes but is not limited to adolescents with allergies and asthma, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, cerebral palsy, or muscular dystrophy. It is a broad population, but all adolescents in this population share a need to understand how to

successfully interact with the health care system, especially as they transition into the adult health care system.

Statewide survey data reveal that 23 percent of Ohio adolescents have SHCN (Chisolm et al., 2013). Adolescents with SHCN are more likely to be from low-income and socioeconomically disadvantaged families (Chisolm et al., 2013). The combination of economic distress and health needs means that they are also more likely to have unmet medical, dental, and prescription medication needs. Adolescents with SHCN require more attention to ensure that they each receive the services they need, and that caregivers and clinicians can help them develop the skills they need to navigate the health care system.

Teen Literacy in Transition Studies: A Health Literacy Lens

Adolescents experience specific health care challenges in that they are starting to take over decision making and their own personal health care management. Unsurprisingly, this can be especially difficult for adolescents with SHCN. During transitions, families must prepare for changes in providers, disease management responsibility, insurance coverage, and more (Rosen et al., 2003). Additionally, less than 18 percent of parents receive desired, comprehensive counseling on how to prepare for transitioning their adolescent children to the independent management of their health care (Strickland et al., 2015).

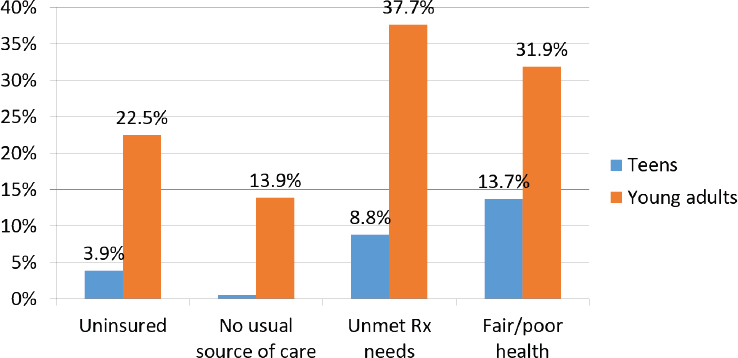

Recent data show that young adults with SHCN and between the ages 18 and 25 are two to three times more likely than their adolescent counterparts to report being uninsured, having no usual source of care, having unmet prescription needs, and reporting fair or poor health (see Figure 4-1). This hurdle to receiving health care in young adulthood can be attributed to a variety of factors, for example, health insurance access or health literacy skills. While the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act1 (ACA) expansion of dependent-child coverage to age 26 increased some transitioning adolescents’ access to health insurance, it only applied to the 53 percent of Americans under 65 who have employer health insurance (Commonwealth Fund, 2019).

Health literacy is also a major component of transition readiness. The Teen Literacy in Transition family of studies, which was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), explored this relationship. The NIMHD study had three main aims (Chisolm, 2018):

- To assess the relationship between adolescent health literacy, parent health literacy, and effective planning for health care transition from adolescence to adulthood.

- To assess the relationship between adolescent health literacy, parent health literacy, and adolescent health indicators, including health-related quality of life and health care utilization.

- To identify mediators and moderators of racial disparity in health literacy in a large, diverse Medicaid-managed-care population of adolescents with special health care needs.

___________________

1 111th Congress, 2010, Public Law 111-148, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, March 23, 2010.

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Deena Chisolm at the workshop on Developing Health Literacy Skills in Children and Youth on November 19, 2019.

Relationships tested will include primary language spoken at home, rural/urban residence, and parental education. The study included Medicaid-managed-care enrollees in Columbus, Ohio, and southeastern Ohio, served by an accountable care organization (ACO) that was associated with Nationwide Children’s Hospital Partners for Kids. Investigators used claims data to identify youth between the ages of 15 and 17 who were diagnosed with 1 of 20 conditions found in more than 90 percent of children with SHCN, and who had been enrolled in Medicaid for at least 12 months, so investigators could have some background data.

Investigators sent letters inviting each family to participate in the study; those expressing interest completed a secondary eligibility screening, which included the following:

- Using the Questionnaire for Identifying Children with Chronic Conditions–Revised (QUICCC–R)2 to confirm that they had a chronic condition

- Ensuring that the participants had English proficiency because investigators were unable to accommodate other languages at the time

- Ensuring that participants had no significant developmental delay

- Establishing what, if any, level of functional limitation participants had

Investigators surveyed primary health care parents and the health care team, assessing word recognition, health literacy skills, self-reported literacy, e-health literacy, transition readiness, and health care utilization from a number of core measures:

- Rapid Evaluation of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM)

- Newest Vital Sign (NVS)

- Brief Health Literacy Screener

- eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) Electronic Health

- Transition Core Indicator

- Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire

- Health care utilization (Medicaid Claims Data)

The sample size was 591 adolescents between ages 15 and 17, with an average age of 16.8 years. Regarding sex, race, and level of functional limitation,

- 48 percent were biologically male and 52 percent were biologically female;

- 58 percent identified as white, 31 percent identified as Black, and 12 percent identified as “other;” and

- 27 percent reported no level of functional limitation, 45 percent reported some level of functional limitation, and 29 percent reported a severe level of functional limitation.3

Though the ACO was based in an urban area, it also covered southeastern Ohio, a rural region otherwise known as Appalachian Ohio.

___________________

2 For more information about QUICCC–R, see https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/documents/QUiCCC_R.pdf (accessed April 20, 2020).

3 Numbers may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding.

General Health Literacy Assessment

The lack of health literacy skills among adolescents with chronic illness is a serious issue. When self-reporting through the Brief Health Literacy Screener, about two-thirds of study participants said that they had adequate health literacy skills, but when participants were assessed with REALM, a word recognition tool, the number dropped to 53 percent. Last, when asked to apply literacy and numeracy skills simultaneously through the NVS, just under 40 percent of participants had adequate health literacy skills, Chisolm explained.

eHealth Literacy Assessment

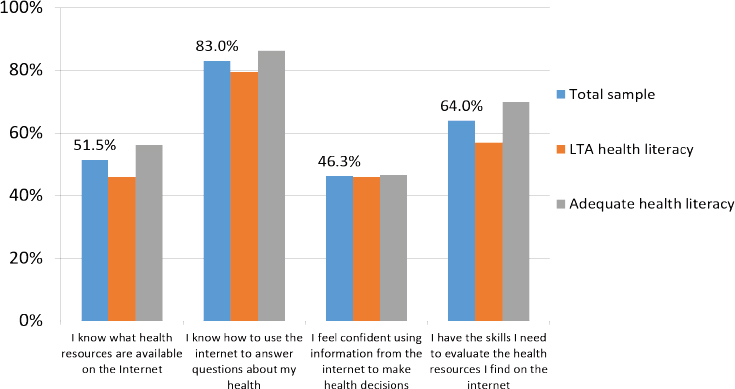

Using the eHEALS e-health tool, investigators also compared participants’ confidence using e-health information with their previously assessed health literacy skills level. When it came to at least four of the eHEALS questions, having adequate or less than adequate (LTA) health literacy had no meaningful impact on the participants’ confidence in their e-health literacy skills (see Figure 4-2). For example, regardless of having adequate or LTA health literacy, 46 percent of study participants agreed that they felt confident using information from the Internet to make health decisions.

Parent Health Literacy

It may be argued that youth health literacy levels are irrelevant because parents or caregivers are present during health care encounters, and clinicians can rely on them to translate or interpret material that is above the health literacy level of the youth. Chisolm and colleagues have shown that, unfortunately, this assumption is incorrect, as 23 percent of their study participants had parents who demonstrated LTA health literacy (Chisolm et al., 2015). Depending on the health literacy assessment, between 47 and 55 percent of parent–teen dyads had concordant adequate health literacy, while between 6 and 11 percent of parent–teen dyads from the study had concordant LTA health literacy (Chisolm et al., 2015). Additionally, between 22 and 36 percent of dyads had a parent with adequate health literacy and a teen with LTA health literacy (Chisolm et al., 2015). Accordingly, it should not be assumed that parents would be able to interpret important health information for their teens.

Racial Disparities in Health Literacy

One of the hypotheses of investigators has been that health literacy skills are not consistent across populations, specifically those differing with

NOTE: LTA = less than adequate.

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Deena Chisolm at the workshop on Developing Health Literacy Skills in Children and Youth on November 19, 2019.

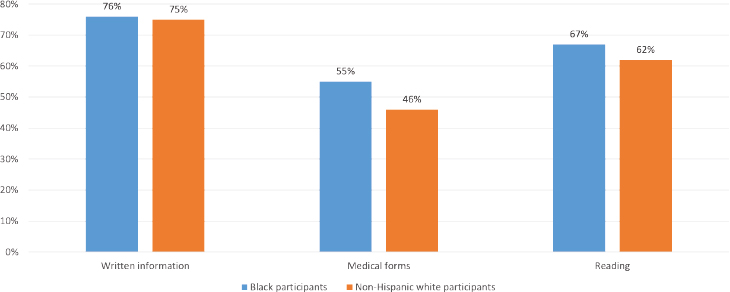

respect to race. In assessed health literacy using both REALM and the NVS, there was a significant gap between Black participants and non-Hispanic white (NHW) participants. In the REALM assessment, 42 percent of Black participants and 54 percent of NHW participants had adequate health literacy, while NVS assessments showed that 26 percent of Black participants and 48 percent of NHW participants had adequate health literacy.4 However, the self-reported health literacy assessment revealed that there was little to no difference in the study participants’ views of their own health literacy skills (see Figure 4-3). Concordance between self-reported and assessed health literacy was much higher among NHW youth than for Black youth in the study. This concordance is another element to consider for those treating youth with SHCN in a health care setting.

Transition Communication

Investigators also examined the relationship between health literacy levels and whether the study participants were having transition discus-

___________________

4 There were no other racial or ethnic groups large enough to compare in this study.

SOURCE: Adapted from a presentation by Deena Chisolm at the workshop on Developing Health Literacy Skills in Children and Youth on November 19, 2019.

sions with their health care providers. Adjusted odds ratios indicated that there was no relationship between participant health literacy levels and having comprehensive transition communication, nor with having discussions about specifically transitioning to an adult health care provider, said Chisolm.

Clinicians were more likely to discuss adult health care needs and insurance with youth with lower health literacy skills than with youth with adequate health literacy skills but were more likely to encourage personal responsibility for health needs among youth with higher literacy levels. One possible explanation for this is that clinicians may have noticed an additional need for communication on needs-based questions with youth with LTA health literacy, and had more belief in the skill sets of youth with adequate health literacy for promoting self-management.

Key takeaways identified by Chisolm for helping teens successfully transition to the adult health care system are noted in Box 4-1.

COMMUNICATING WITH A HIGH-RISK YOUNG ADULT POPULATION: W.E.I.G.H.T. STUDY

Gail Nunlee-Bland, Howard University College of Medicine

Background in Earlier Diabetes Research

Between 1996 and 2009, AARP and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conducted a study that concluded that individuals who gain weight and have a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 25 at age 18 will have a twofold increase in mortality risk compared with individuals who have a BMI greater than or equal to 25 at age 50 (Adams et al., 2014).

Between 1996 and 1999, NIH conducted another study to investigate the efficacy of different interventions for individuals at high risk for developing diabetes (DPP Research, 2002). The study’s control group had no intervention, the second group was given a drug that was known to prevent or delay the onset of diabetes (metformin), and the third group was given a lifestyle intervention that included a case manager, supervised exercise sessions, culturally and linguistically appropriate educational materials, and more (DPP Research, 2002). The incidence of diabetes in the control group was 11 percent; the incidence in the group taking metformin was 7.8 percent; and the incidence in the group with lifestyle interventions was 4.8 percent (Knowler et al., 2002), demonstrating that the lifestyle intervention was by far the most effective at preventing or delaying the onset of diabetes. The average age of these study participants was 51 years.

W.E.I.G.H.T. Study

To adapt the W.E.I.G.H.T. (Working to Engage Insulin-Resistant Group Health Using Technology) study for young adult participants, Nunlee-Bland and colleagues started with a behavior-change counseling system known as Avoiding Diabetes thru Action Plan Targeting: T2D Prevention (ADAPT). The ADAPT system included behavior-change principles and persuasive psychology similar to the NIH lifestyle intervention study, but it also included a technology component: website-based, tailored reminders; frequent feedback about progress via e-mail and text; and other factors (Mann and Lin, 2012). The W.E.I.G.H.T. study aimed to “compare the effectiveness of a lifestyle change intervention delivered either using state-of-the-art communications or networking technologies or using lifestyle group visits” (Nunlee-Bland, 2020). The design was a nonmasked, randomized interventional parallel assignment trial, and participants were required to be African American, between 18 and 24 years old, with an impaired fasting blood glucose between 100 and 125, with a family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and with a BMI greater than or equal to 25. Participants were ineligible for the study if they were pregnant, unwilling to participate, had no web-enabled cell phone, had previously been diagnosed with diabetes, or had been previously diagnosed with a significant chronic illness.

Among other factors, investigators scored the following for the participants: Patient Activation Measure (PAM)-10 (see Box 4-2), Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ 9), Physical Activity–Godin Leisure Time, motivation for weight loss, the NVS, International Physical Activity Questionnaire, height, weight, BMI, and fasting blood glucose. The primary outcome for

the W.E.I.G.H.T. study was improved patient activation; Nunlee-Bland and colleagues hoped that the final 172 participants would leave the study feeling more in control of their own health. Secondary outcomes included lowered BMI and hemoglobin A1c. The participants were divided into two groups: The Lifestyle Group Visits participants followed the Diabetes Prevention Protocol interventions. The participants worked in a workbook, tracked a log of their steps and calories, and used a CalorieKing book to look up calorie counts for foods they were eating. Participants in this group logged everything in a journal and met with a lifestyle coach for about 1 hour each week for 12 weeks.

The second group was the “tech group.” They were not required to come in person for weekly visits—every study component was available online. Participants received weekly compliance text reminders to encourage participants to take 10,000 steps daily and to make healthy choices about foods. The tech group participants also downloaded the MyFitnessPal and FitBit apps so they could record their caloric intake and track movement. Investigators provided the participants with personal health records from the Howard University Hospital Diabetes Treatment Center, which were integrated into and linked with their individual MyFitnessPal accounts.

Using the curriculum from the Group Lifestyle Balance Program developed at the University of Pittsburgh, Nunlee-Bland and colleagues developed their curriculum with pragmatics in mind. Participants were supplied with measuring spoons and cups for portion sizes, body scales, and, for the tech group, FitBits to correspond with their mobile apps.

After 12 weeks, 104 participants finished the study. The baseline characteristics between the tech and nontech groups—weight loss, PAM-10 scores, motivation for weight loss—were not notably different. However, during a 12-month follow-up (which included 64 participants), investigators found that the tech group had a significantly lower PHQ 9 score and better sleep habits, and that they were also more physically active.

Over time, the tech group became much more activated in their own health management, though there were no differences between BMIs or A1c changes over time. There are a few possible reasons for these results. As many as 75 percent of people between ages 18 to 29 get the majority of their health information using a smartphone (Smith and Pew Research Center, 2015) compared with 62 percent of the general population, suggesting that smartphones can be a crucial tool for sharing health information with young adults. Additionally, after 1 hour, people retain less than half of the information presented to them. After 6 days, they forget 75 percent of that information. The tech group was required to take quizzes and have minimum pass scores regarding health, whereas the control (nontech) group did not, possibly affecting retention of information. Overall, technology including smartphones and apps may be useful for reaching late adolescent and young adult populations to engage them in their health care.

HEALTH LITERACY IN YOUNG ADULTS AGING OUT OF FOSTER CARE5

Steven Hoffman, Brigham Young University School of Social Work

Youth in Foster Care

Approximately 437,465 youths are in U.S. foster care, with about 25 percent residing in relatives’ homes; 45 percent residing in nonrelatives’ homes; and 12 percent residing in residential or group homes (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2017). About 55 percent of youth are “in the system” for more than 1 year. Youth who are adopted or reunified with family are no longer considered to be “in the system” (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2017). A disproportionate number of youths in the foster care system are racial or ethnic minorities.

Youths in the system have an increased likelihood of chronic health conditions, substance use, and behavioral or mental health disorders, and they often struggle with health across the board (Council on Foster Care et al., 2012; Jones, 2014; Vestal, 2014). It is important to note that youths in the foster system should not be considered “bad,” as they are occasionally generalized. They have often had challenging childhoods compared with youths not in the foster care system. Youths in the system are also more likely to be homeless—between 31 and 46 percent have been found to experience homelessness at least once before age 26.

While working at Boys Town, a large residential treatment center in Nebraska, Hoffman assessed the health literacy of patients while they were in care, and then investigated educational outcomes after they left. Although the patients were not necessarily doing “terribly well” while in treatment, any educational gains they might have made had completely disappeared after they left treatment. Often, those patients were reading three to five levels below their grade level, and many of them would not graduate high school. In a residential treatment program like Boys Town, those patients might get “bumped up” by having intensive planning and training, but when they return to their community with the same people or situations they left, which may not be positive, they have a “big drop” in educational skills. Because health literacy is correlated strongly with educational outcomes, this is a problem.

___________________

5 A note about the limitations of the conclusions drawn from data presented during Steven Hoffman’s presentation: The information for this presentation comes from two exploratory studies with small sample sizes focused on individuals facing unique circumstances. Information gathered does help to formulate an initial understanding of these populations but should not be considered conclusive or generalizable. Additional studies looking at youth formerly in foster care and Preparation for Adult Living program curricula across states are needed before firm recommendations can be made.

Former Foster Youth and Health Literacy

Youth who have grown up in the foster system face significant challenges that may put them at a higher risk of having limited health literacy (Shah et al., 2010; Trout et al., 2014) (see Box 4-3). They experience high rates of mobility—between five and seven foster home placements over the course of a few years. This can make it very difficult to maintain health records, in addition to the problem of lacking caregivers who might be aware of family medical history.

It is required that youth new to the foster care system be seen by a doctor and psychologist within their first few months. However, after the initial checkup, any health care they receive is often crisis care—a response to issues as they arise—as opposed to regular preventive care. When youths age out of foster care, they lose some state support services, one of the biggest of which is housing. The ACA was helpful in maintaining some access to health insurance, and there are certainly a lot of services that remain available to recently aged-out young adults, but those young adults may not be aware of them. They also often do not have any adult to turn to—they may have a case manager, but they also may never have met that case manager. In general, young adults transitioning out of the foster system may be inadequately prepared for the transition to adult living, and they have high rates of experiencing homelessness and unemployment.

Young Adult Medicaid Study

There are some services, like Preparation for Adult Living (PAL) programs, that have been instituted across several states to help youth prepare to manage their own health and lives. In Texas, a state-sponsored provider

of post–foster care services for youth provided a PAL facility and program in collaboration with a team of researchers at The University of Texas at San Antonio. The PAL case managers helped young adults who had recently aged out of the foster care system, mainly with employment and housing concerns.

Researchers recruited study participants from those in the PAL program, using e-mail, text messages, and talking with participants when they came into the PAL facility for checkups. Researchers used surveys, assessments, and small focus groups with a sample of 57 young adults between the ages of 18 and 26 who had aged out of foster care. About half of the sample identified as women, 56 percent of participants identified as Hispanic and/or Latinx, and 14 percent of participants identified as Black. Researchers used the NVS tool, although the focus groups conversation mainly steered toward critical health literacy. Based on the NVS tool, about 28 percent of the sample had adequate health literacy.

Compared with other populations where educational attainment is considerably higher, Hoffman and his colleagues knew that educational attainment would be a challenge for this population of foster youth, and because health literacy is strongly correlated with education, health literacy skills development was also expected to be a challenge. Existing research informed the researchers that fewer than 2 percent of the sample would go on to obtain a bachelor’s degree, and the majority of them would never graduate high school. With high rates of homelessness and unemployment among the foster youth population, the case managers reported to the researchers that they focused primarily on meeting baseline checkpoints (housing, employment, health care), necessarily delaying a major focus on education and thus delaying a large building block of health literacy skills development.

Of note, every single focus group in the study had participants that were not aware that they were covered with former foster youth Medicaid health insurance until age 26. Some system-level issues that were difficult to navigate included the following:

- Automatically being removed from Medicaid coverage, requiring the individual to find out that they were no longer covered, call their case manager, and confirm that they are a former foster youth and do not have a job that covers health insurance

- Being provided with thick books listing local providers who accepted their insurance—except the books were usually outdated, and most of the providers no longer accepted their Medicaid plan

- Having to use a significantly outdated online patient portal system, requiring case managers to spend 3–4 hours on the phone with individuals to help them find a Medicaid customer service repre

sentative who was knowledgeable about the specific former foster youth group

While the PAL program used by Hoffman’s collaborating partners in San Antonio taught important life skills and subjects like banking, nutrition education, and sex education, it did not teach about health insurance, or navigating the health care system. An informal survey of states providing PAL programs revealed that the curricula are focused largely on nutrition education and sex education. There is inconsistency across and within states: Many states contract their programs out, and others operate independently, county by county. States that do have a statewide curriculum have little emphasis on critical health literacy so, practically, the existence of a PAL program does not provide any tangible health literacy skills development among youth aging out of foster care. The PAL programs could be significantly improved by providing critical health literacy training. Steven Hoffman’s proposed recommendations for future research and practice can be found in Box 4-4.

DISCUSSION

Arvanitis opened the discussion by asking all of the panelists what their research in special populations may be able to teach the workshop about promoting health literacy among all youth.

Chisolm replied that the right approach is likely modular, with some core foundational skill sets that every young person needs and that are age appropriate but, beyond that, there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach. Nunlee-Bland agreed, adding that the patient needs to be the center of their own health. The concepts of patient centeredness and activation are a major part of her own research focus. Hoffman added that the parent–child relationship should also be considered given that a number of studies support the importance and relationship of parents’ health literacy to their child’s health literacy and health outcomes.

Chisolm agreed and added that the parent–child relationship is more complex than sometimes acknowledged. For example, there are parents with high levels of health literacy and who are engaged with their children who do not allow their children to transition to self-managing their care, leading to teens and young adults with low self-efficacy and low self-advocacy because they have not been empowered by their parents. On the other end of this spectrum, there are parents juggling care for multiple children, their own multiple health issues, and even holding multiple jobs, who may rely on their child to manage their own health at a younger age because they are unable to manage it for them. It is important to recognize that the relationship between parent and child is different for each family, and all of those components need to be accounted for when building a model to promote health literacy among all youth.

Trina Anglin, formerly from the Health Resources and Services Administration, noted that since 2011, if states have PAL programs, they are required by the Administration for Children and Families to participate in the National Youth in Transition Database, reporting on six areas, all of which are related to health literacy:

- Financial self-sufficiency

- Experience with homelessness

- Educational attainment

- Positive connections with adults

- High-risk behaviors (as measured by involvement with the criminal–legal system, among other factors)

- Access to health insurance

These data can be accessed at the National Youth in Transition Database within a series of briefs. Unfortunately, Anglin noted, they stop at 2017.

Hoffman added that these data were informative, though the questions were more focused on whether the young adult had health insurance, not whether they could manage it, and there should be more qualitative data collected.

Earnestine Willis from the Medical College of Wisconsin asked whether states required preparation for PAL programs. For example, in prisons, transition programs must begin 6 months prior to discharge. Willis also asked whether Hoffman had any other proposed system changes. Hoffman was unsure about every state’s requirements but confirmed that Texas started PAL programs about 1 year prior to discharge from the foster system, with monthly meetings. He noted that considering the cognitive developmental frameworks discussed earlier in the day, starting transition readiness programs “the year before youth turn 18 is probably a little late.”

Hoffman added that if he could choose one recommendation, it would be how PAL programs are delivered, adding, “Most states are doing something, and we can change or mandate content, but delivery is often a challenge.”

The NVS, REALM, and Other Assessment Tools

Hannah Lane from the Duke University School of Medicine noted that each panelist used the NVS in their work. The NVS has been validated for use in children and adolescents, though only from a few studies. Lane noted, “I think a larger conversation needs to be had among health literacy researchers and those collecting data on health literacy with children about whether or not the NVS is appropriate, or if it is sufficient, and if we need to develop modifications for using it to assess children.”

Nunlee-Bland noted that she was particularly interested in using the NVS because her research was mainly focused on nutrition and health, specifically looking to see if study participants were able to read a food label and understand caloric intake. The NVS was a useful tool for assessing that among her college-aged population.

Chisolm said that the NVS is limited, so her team used the NVS with REALM. One of the reasons they used the NVS in addition to REALM was because participants capped out of the REALM assessment; they also had significant challenges using it. Chisolm explained, “Some of the younger people and even some parents just found the NVS too difficult. They were willing to walk away from the whole study if they were required to answer those questions.” The information was helpful for the investigators but the respondent burden was high, and there is a lot more work to do to improve measurement and assessment.

Terry Davis from Louisiana State University Health Shreveport explained that she developed REALM and its derivatives, and that none

of the assessments measure health literacy. She noted, “REALM measures literacy, which is a marker for health literacy.” She believes that the best assessment for health literacy is teach-back.

Arvanitis noted that there are a number of recent systematic reviews of existing child-focused health literacy measures (e.g., Okan et al., 2018), and one criticism was that the measures were not developmentally appropriate. Manganello added that she does not look at tools like the NVS or REALM as measures of health literacy, but more to compare groups, as markers to assess change over time, or to see differences among groups. She acknowledged that it can be difficult trying to submit a grant proposal for intervention research, because funders want investigators to use a validated tool, but it can be difficult to access funding to validate newer tools.

Annlouise Assaf from Pfizer Medical and Safety added that one of the best uses for the NVS was in a health care provider’s office. Because it is a short assessment, it would give the health care provider an idea of what level of understanding a patient may have for the content the provider is presenting. And rather than burden the patient to increase their health literacy level, the burden is placed on providers and pharmaceutical companies to ensure that their materials are optimized and tailored in a way such that the patient would understand them fully.

Davis noted that her research showed that using the NVS could interfere with doctor–patient relationships because patients were ashamed or embarrassed about their literacy skills. She asked, “What does it mean to a doctor that your EHR [electronic health record] says you read at a middle-school level? Does the clinician have the skills to communicate effectively with the patient in an appropriate manner?” She is a firm believer in using assessments like the NVS for research but is more cautious about their clinical utility.

Arvanitis noted that her colleagues are considering using the Brief Health Literacy Screener as part of clinical care. She agreed that there are many limitations in that they might flag patients with low levels of health literacy, but it depends on the intentions of the assessor. She agreed that it would be difficult to roll out something as potentially challenging and frustrating as the NVS in a clinical environment.

Christopher Trudeau from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences asked how the NVS or a similar type of assessment conducted in a clinical setting might affect the way resources are allocated in health systems.

Nunlee-Bland said that the NVS is useful for ascertaining a patient’s baseline literacy level and using that information to help increase their skills. She and her colleagues tailored healthy lifestyle information for their participants and used the NVS to assess whether those materials improved their knowledge.

Chisolm noted that she is not conducting health literacy screenings in a clinical setting. She believes health literacy is more effective as a population--

level measure than as a practice or clinical-level measure. In the clinical setting, she said, “universal precautions should rule the day,” and teach-back and plain language should be the standard for care delivery. However, it is important to use tools like the NVS to understand a population and know what their limitations are, because populations with 30 percent or 90 percent low health literacy levels would require different approaches in terms of interventions.

Laura Noonan from Atrium Health noted that using validated tools in clinical settings can be confusing for families, especially when this affects treatment. For example, the Juvenile Arthritic Disease Activity Score is a validated tool used to identify juvenile idiopathic arthritis, but the questions only ask about the past week of the child’s health, as opposed to the past several weeks or months. These were validated in research for research purposes, she said, but does that mean they are useful in a clinical context?

Sarah Benes from Merrimack College and SHAPE America said that an important component in moving forward is how to bridge the gap between developing evidence-based measures and implementing them quickly enough that they positively affect health outcomes.

Chisolm added that researchers and implementers need to start thinking about the “acquisition of knowledge” component as opposed to the “knowledge” component or measure, because some skills can quickly become outdated, but the ability to develop and grow skills will always be important.

e-Health and Technology

Manganello asked how the panelists see technology or the online environment specifically being able to help the unique populations they work with, if at all.

Chisolm noted that she conducted a number of focus groups when her team was developing their e-health literacy video set. They had considered developing apps, but their focus group participants did not want them. Ultimately, their team hired two 16-year-olds to evaluate the videos they designed, which proved to be very helpful. Chisolm added that health systems and organizations need to be flexible enough to keep up with youth because whatever technology is best used one year among youth to share health information will be considered passé the next.

Hoffman noted that one of his two takeaways from the former foster youth study he conducted in San Antonio was that everyone should have a phone. He also thought that e-health literacy might be able to mitigate some of the lack of trust with the system, so that youths aging out of foster care can successfully navigate the online world, especially when they are unable to turn to family, parents, or a good social support network.

Activation and Transition Readiness

Arvanitis asked the panelists how they saw activation or transition readiness relating to health literacy among youth. In adults, she said, there is some evidence that they are independently affecting health outcomes, but is it the same case with youth? What research needs to be done?

Nunlee-Bland said that in her work with a young adult population, the patient activation measure correlated with adult literature in terms of improvement and in terms of health outcomes. Participants became more motivated in losing weight or maintaining weight loss, in knowing how to speak with their doctor, and in knowing when and how to take their medications.

Hoffman noted that the connection between actual health literacy and health outcomes is fuzzy and only gets fuzzier the younger the population is.

Chisolm explained that from her research, transition readiness and health outcomes appear to be independent. They do have some relationship, she said, but it is not very strong. In her research, reviewing health care utilization and outcomes going forward, there does not appear to be a significant relationship with transition readiness. As a researcher, the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) could be frustrating because it is not always clear if the lack of significant relationship means that they were measuring the wrong thing or measuring in the wrong way, or even asking the wrong questions. “I think there is still a lot of opportunity,” she said. “I think TRAQ is a great tool, and there is still opportunity to refine it to be more predictive of actual health care utilization and outcomes over time.”

REFERENCES

Adams, K. F., M. F. Leitzmann, R. Ballard-Barbash, D. Albanes, T. B. Harris, A. Hollenbeck, and V. Kipnis. 2014. Body mass and weight change in adults in relation to mortality risk. American Journal of Epidemiology 179(2):135–144. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt254.

Child Welfare Information Gateway. 2017. Foster care statistics 2017. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/foster.pdf (accessed May 5, 2020).

Chisolm, D. 2018. Project information: Health literacy disparities and transition in teens with special healthcare needs. NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools. https://grantome.com/grant/NIH/R01-MD007160-04 (accessed September 18, 2020).

Chisolm, D., K. Steinman, L. Asti, and E. R. Earley. 2013. Emerging challenges of serving Ohio’s children with special health care needs. Columbus, OH: The Ohio Colleges of Medicine Government Resource Center. http://grc.osu.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Emerging%20Challenges%20of%20Serving%20Ohio%27s%20Children%20with%20Special%20Health%20Care%20Needs%20Report.pdf (accessed July 30, 2020).

Chisolm, D. J., M. Sarkar, K. J. Kelleher, and L. M. Sanders. 2015. Predictors of health literacy and numeracy concordance among adolescents with special health care needs and their parents. Journal of Health Communication 20(Suppl 2):43–49. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1058443.

Commonwealth Fund. 2019. Table 1. Insurance status by demographics, 2018. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/Collins_hlt_ins_coverage_8_years_after_ACA_2018_biennial_survey_tables.pdf (accessed May 5, 2020).

Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care and Committee on Early Childhood. 2012. Health care of youth aging out of foster care. Pediatrics 130(6):1170–1173. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2603.

DPP (Diabetes Prevention Program) Research Group. 2002. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): Description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care 25(12):2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165.

Hibbard, J. H., J. Stockard, E. R. Mahoney, and M. Tusler. 2004. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Services Research 39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x.

Jones, L. 2014. Health care access, utilization, and problems in a sample of former foster children: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work 11(3):275–290. doi: 10.1080/15433714.2012.760993.

Knowler, W. C., E. Barrett-Connor, S. E. Fowler, R. F. Hamman, J. M. Lachin, E. A. Walker, D. M. Nathan, and Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. 2002. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. The New England Journal of Medicine 346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa012512.

Mann, D. M., and J. J. Lin. 2012. Increasing efficacy of primary care-based counseling for diabetes prevention: Rationale and design of the ADAPT (Avoiding Diabetes thru Action Plan Targeting) trial. Implementation Science 7:6. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-6.

Nunlee-Bland, G. 2020. Howard University College of Medicine research: W.E.I.G.H.T. https://medicine.howard.edu/about-us/research/dc-baltimore-research-center-child-health-disparities/about-us/weight (accessed May 5, 2020).

Okan, O., E. Lopes, T. M. Bollweg, J. Broder, M. Messer, D. Bruland, E. Bond, G. S. Carvalho, K. Sorensen, L. Saboga-Nunes, D. Levin-Zamir, D. Sahrai, U. H. Bittlingmayer, J. M. Pelikan, M. Thomas, U. Bauer, and P. Pinheiro. 2018. Generic health literacy measurement instruments for children and adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health 18(1):166. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5054-0.

Rosen, D. S., R. W. Blum, M. Britto, S. M. Sawyer, D. M. Siegel, and Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2003. Transition to adult health care for adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions: Position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. The Journal of Adolescent Health 33(4):309–311. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00208-8.

Shah, L. C., P. West, K. Bremmeyr, and R. T. Savoy-Moore. 2010. Health literacy instrument in family medicine: The “newest vital sign” ease of use and correlates. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 23(2):195–203. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.070278.

Smith, A., and Pew Research Center. 2015. U.S. Smartphone use in 2015. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015 (accessed May 5, 2020).

Strickland, B. B., J. R. Jones, P. W. Newacheck, C. D. Bethell, S. J. Blumberg, and M. D. Kogan. 2015. Assessing systems quality in a changing health care environment: The 2009–10 national survey of children with special health care needs. Maternal and Child Health Journal 19(2):353–361. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1517-9.

Trout, A. L., S. Hoffman, M. H. Epstein, T. D. Nelson, and R. W. Thompson. 2014. Health literacy in high-risk youth: A descriptive study of children in residential care. Child & Youth Services 35(1):35–45. doi: 10.1080/0145935X.2014.893744.

Vestal, C. 2014. States enroll former foster youth in Medicaid. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2014/04/30/states-enroll-former-foster-youth-inmedicaid (accessed May 5, 2020).