8

The Transition from Adolescence to Young Adulthood

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) defines the adolescent and young adult (AYA) population as patients diagnosed with a first cancer between ages 15 and 39. This population is recognized as one with inferior treatment and survivorship outcomes compared with younger and older patients with cancer. The reasons for this include fewer patients being enrolled in clinical trials, differences in approach between providers of pediatric and adult cancer care, delays in diagnosis, and psychosocial and cognitive impacts at a critical juncture of development. As is the case in younger populations, cancer symptoms may improve with therapy, but recovery may not be complete. Survivors may experience long-term functional impacts both from permanent destructive effects of the tumor itself and from detrimental effects of treatment.

A cancer diagnosis during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood has broad implications for both current and future disabilities. Given these implications, the discussion in this report of late effects impacting physical, psychosocial, emotional, and cognitive functioning is extended to include survivors of cancer over the age of 18 and into their 20s. Important issues, such as the risks for infertility or the ability to maintain health insurance through a parent’s plan until age 26, are unique to this AYA period.

Importantly for this study, this age range also spans childhood and adulthood, for which the U.S. Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) disability determination process differs: the child adjudication process is based on functional equivalence to peers, while the adult adjudication process is based on medical–vocational evaluations. As individuals transition to

adulthood, disability determinations are affected by both immediate and future consequences of cancer and its treatment.

THE DISABILITY DETERMINATION PROCESS

Differences Between Child and Adult Disability Determinations

A child who applies to SSA for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) may be awarded disability benefits if he or she has a medically determinable physical or mental impairment or combination of impairments that results in “marked and severe functional limitations” (SSA, 2020a). As discussed in Chapter 1, this determination is made through a three-step process. Following a determination of administrative eligibility and the presence of a medical impairment of sufficient severity and duration, SSA determines whether the child’s qualifying impairment(s) meets or medically equals (is equivalent in severity to) the criteria in the Listing of Impairments (listings), or functionally equals the listings (SSA, 2020a,b). The listings describe, for each of the major body systems, impairments that SSA considers to be severe enough to cause marked and severe functional limitations in children. In making this determination, SSA evaluates the child’s functioning compared with that of same-age children who do not have impairments.

In contrast, SSA’s definition of disability for adults is the “inability to do any substantial gainful activity [SGA] by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”1 In 2020 a non-blind individual must not earn more than $1,260 per month after deduction of impairment-related work expenses (SSA, 2020c). The adjudication process for adults is based on medical–vocational evaluations and consists of five steps used for determining whether an adult meets the definition of disability. After determining administrative eligibility and the presence of a medical impairment of sufficient duration and severity, SSA assesses, in Step 3, whether an applicant’s impairment meets or equals a condition included in the listings (SSA, 2010). Step 3 serves as a “screen in” step. If an impairment is severe but does not meet or medically equal any listing, the applicant proceeds to Step 4. In Step 4, SSA assesses whether applicants’ physical or mental residual functional capacity (RFC) allows them to perform past relevant work. Applicants able

___________________

1 20 CFR 416.905.

to perform past relevant work are denied benefits, while applicants unable to do so proceed to Step 5. At Step 5, SSA considers applicants’ RFC and such vocational factors as age, education, and work experience, including transferable skills, in determining whether they can perform other work in the national economy. Applicants determined to be unable to adjust to performing other work are allowed benefits, while those determined able to adjust are denied.

SSA organizes the medical criteria for impairments—their listings—by age (adult [18 years of age and older]; child [less than 18 years of age]) and by body systems. Cancer is listed as its own body system: Cancer (Malignant Neoplastic Diseases) (SSA, 2020b). Regardless of where the cancer originates in the body, it is evaluated under the medical criteria for SSA’s cancer body system. For each cancer category, SSA considers factors including “origin of the cancer; extent of involvement; duration, frequency, and response to therapy; [and] effects of any post-therapeutic residuals” (SSA, 2020b). The SSA cancer listings for children include 8 categories of cancers, while the listings for adults include 28 categories. Several cancers enumerated in the adult listings are grouped together in the child listings. For example, the child cancer listings include a category of “malignant solid tumors,” which encompasses any malignant solid tumors that are not otherwise specified in the listings. In contrast, most solid tumors are called out individually in the adult cancer listings (e.g., soft-tissue sarcoma; skeletal system sarcoma; carcinoma of the kidneys, adrenal glands, or ureters).

Age-18 Redeterminations

When an individual turns age 18, SSA reviews his or her eligibility to continue receiving SSI benefits based on the SSA disability determination process for adults. This review process, called the age-18 redetermination, includes evaluation under nonmedical eligibility rules, as outlined above. The differences between the child and adult determination processes will affect all individuals, not just those with cancer diagnoses. Some survivors may be processed through a redetermination for a noncancer listing.

About one-third of children lose their eligibility for SSA benefits following their age-18 redetermination (SSA, 2020d). Following this decision, an individual may request an appeal within 60 days of notification of the decision. If an appeal is requested within 10 days of receipt of the notification, the individual may choose to have SSI benefits continue

during the appeal process (SSA, 2020d). The age-18 redetermination is processed differently from a new application. Meeting the earnings threshold for SGA does not automatically make an individual ineligible for SSI. Rather, SSA will consider whether earnings that exceed the SGA level are due to SSI work incentives or other supports (SSA, 2020d).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF CANCERS IN ADOLESCENTS AND YOUNG ADULTS

While the disability determination process changes abruptly at the age of 18, the epidemiology of cancers across the AYA age range shows a gradual transition in cancer types and incidence from childhood to adulthood. It is estimated that in the United States, approximately 70,000 individuals in the AYA age range are diagnosed with cancer annually, a figure that represents approximately 5 percent of the nation’s total cancer burden (Howlader et al., 2019). The first several years of the AYA age range include individuals who are under the age of 18, and it is important to consider disability related to cancer diagnosis and treatment during this period of transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Annual Incidence Rates

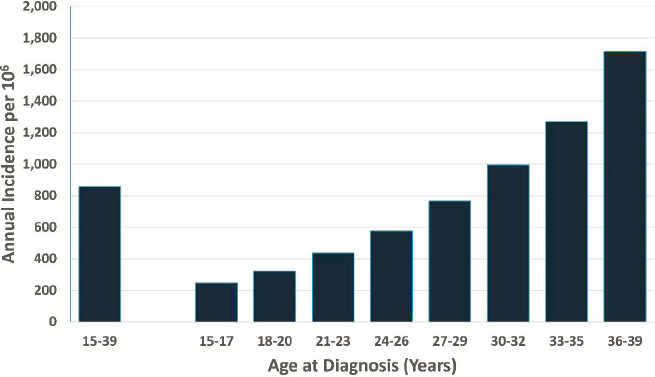

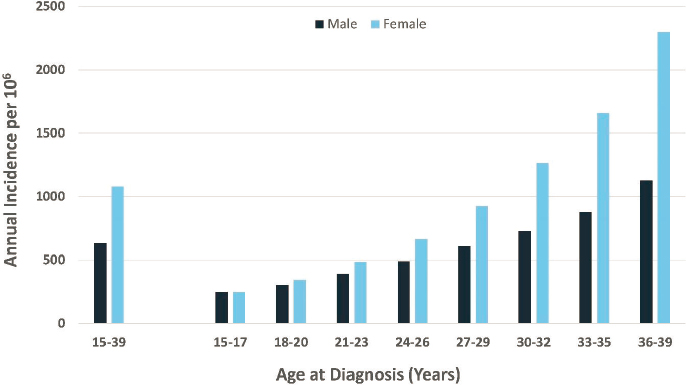

NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program is the primary source of population-based data on cancer incidence in the United States (Howlader et al., 2019). The overall annual U.S. incidence of cancer for the AYA age range is 856.9 per million population,2 increasing from 248.4 for ages 15–17 to 1,714.8 for ages 36–39 (see Figure 8-1). The sex-specific annual U.S. cancer incidence is markedly higher among females (1,080.6/106) than among males (633.6/106), a difference related largely to breast cancer (see Figure 8-2).

Table 8-1 presents the overall and diagnosis-specific incidence rates of various cancers for the AYA population (ages 15–39). Also presented are age-specific incidence rates for four age groups between ages 15 and 26. These rates show a decline in incidence with increasing age for diagnoses common in the pediatric age range, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. In contrast, the rates for these four age groups show increases for lymphomas (both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin); germ cell neoplasms; melanoma; thyroid cancer; breast cancer; and malignancies of the respiratory, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal tracts.

___________________

2 Since the prepublication copy of the report was released, the denominator for the incidence reported was corrected from “per 100,000” to “per million.”

SOURCE: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program for the period 1990–2016.

SOURCE: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program for the period 1990–2016.

TABLE 8-1

Annual Incidence of Various Cancers in Adolescents and Young Adults

| Diagnosis | Annual Incidence/106 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AYA (ages 15–39 years) | Ages 15–17 Years | Ages 18–20 Years | Ages 21–23 Years | Ages 24–26 Years | |

| All Histology | 856.9 | 248.4 | 323.1 | 436.5 | 576.8 |

|

42.2 | 31.8 | 28.5 | 26.9 | 26.4 |

| Acute lymphoid leukemia | 9.5 | 19.1 | 13.4 | 9.8 | 7.7 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 12.6 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 10.8 | 10.9 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 6.5 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 5.7 |

| Other and unspecified leukemia | 3.9 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.2 |

|

80.8 | 46.7 | 60.7 | 72.4 | 76.4 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 42.6 | 18.9 | 20.4 | 26.2 | 31.4 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 38.2 | 27.8 | 40.3 | 46.2 | 45.1 |

|

55.4 | 33.4 | 30.2 | 35.1 | 44.1 |

| Astrocytoma | 15.8 | 13.7 | 11.1 | 11.6 | 13.8 |

| Other glioma | 9.2 | 8.2 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 3.9 |

| Ependymoma | 3.0 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 3.2 |

| Medulloblastoma and other PNET | 1.9 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| Other specified intracranial and intraspinal neoplasms | 23.2 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 10.8 | 14.7 |

| Unspecified malignant intracranial and intraspinal neoplasms | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

|

9.8 | 18.4 | 13.2 | 9.8 | 8.2 |

| Osteosarcoma | 3.8 | 10.1 | 6.4 | 3.7 | 2.7 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 2.1 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Ewing tumor | 2.8 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| Other specified and unspecified bone tumors | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

|

29.7 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 19.1 | 24.1 |

| Fibromatous neoplasms | 7.5 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 5.1 | 6.6 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1.6 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Other soft-tissue sarcoma | 20.5 | 8.0 | 9.3 | 12.5 | 16.5 |

|

60.5 | 21.8 | 40.4 | 59.9 | 72.9 |

| Germ cell and trophoblastic neoplasms of gonads | 56.0 | 16.8 | 35.5 | 55.1 | 67.5 |

| Germ cell and trophoblastic neoplasms of nongonadal sites | 4.5 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 5.3 |

|

71.5 | 10.5 | 20.8 | 36.7 | 55.4 |

| Melanoma | 70.6 | 10.2 | 20.6 | 36.3 | 54.9 |

| Skin carcinomas | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

|

385.7 | 36.0 | 63.7 | 109.2 | 182.0 |

| Thyroid carcinoma | 102.4 | 20.3 | 36.3 | 58.3 | 82.2 |

| Other carcinoma of head and neck | 16.3 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 6.9 | 9.1 |

| Carcinoma of trachea, bronchus, and lung | 11.6 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 4.1 |

| Carcinoma of breast | 107.6 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 5.8 | 21.3 |

| Carcinoma of genitourinary tract | 82.7 | 3.5 | 7.5 | 16.4 | 35.7 |

| Carcinoma of gastrointestinal tract | 59.5 | 6.1 | 10.6 | 16.9 | 26.4 |

| Carcinoma of other and ill-defined sites | 5.7 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 3.1 |

| Diagnosis | Annual Incidence/106 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AYA (ages 15–39 years) | Ages 15–17 Years | Ages 18–20 Years | Ages 21–23 Years | Ages 24–26 Years | |

|

19.1 | 7.0 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 11.8 |

| Other pediatric and embryonal tumors, NOS | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Other specified and embryonal tumors, NOS | 18.0 | 5.3 | 7.0 | 8.2 | 11.1 |

|

4.0 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

NOTE: AYA = adolescent and young adult; CNS = central nervous system; NOS = not otherwise specified; PNET = primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

* Since the prepublication copy of the report was released, the AYA incidence rates for soft-tissue sarcomas and carcinomas were corrected from 3.7/106 to 29.7/106 and from 9.6/106 to 385.7/106, respectively.

SOURCE: National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program for the period 1990–2016.

Incidence of Subsequent Cancers Among Adolescents and Young Adults

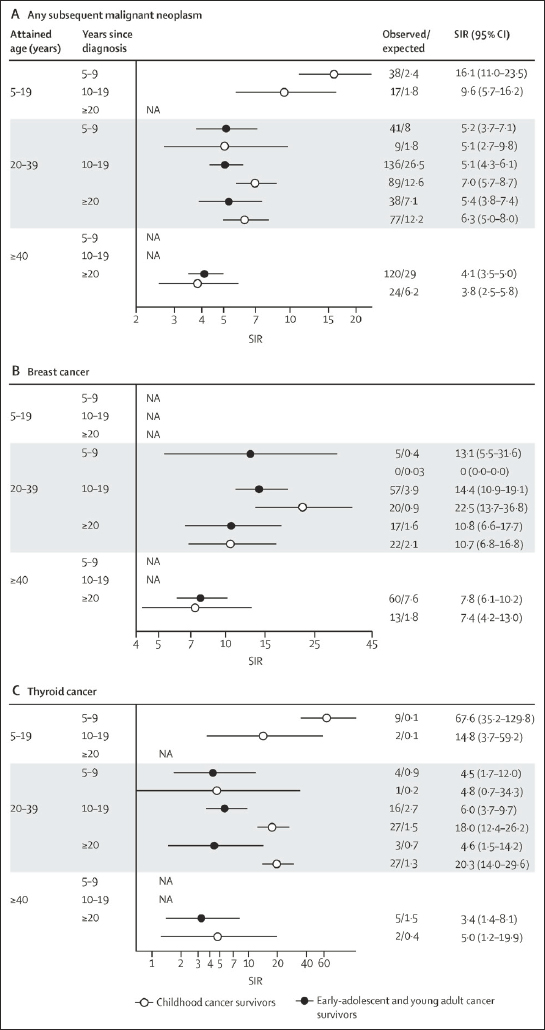

As discussed in Chapter 4, long-term survivors of childhood cancer are at risk for new primary malignancies due to radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and genetic predisposition. Most studies have examined the risk of secondary malignant neoplasms (SMN) for all survivors of childhood cancer (aged 20 years or younger at diagnosis) or all survivors of AYA cancer (aged 15–39 years at diagnosis), but have not focused on the risk for those aged 15–19 years—the early AYAs on whom this report focuses. In the British Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Survivor study, in which 12,248 survivors of childhood cancer treated for their primary cancer between the ages of 15 and 19 years were observed, 622 (5 percent of survivors) developed an SMN (Bright et al., 2019).

An analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study examined the risk of SMN in survivors of early-AYA cancer and compared their risk with that of survivors diagnosed as children (below age 15 years). Risk of SMN for both groups relative to age-matched, calendar-year-matched, and sex-matched members of the general population was evaluated and reported as standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) for both groups. The risk of SMN for survivors of early-AYA cancer was almost five fold that for the general population (SIR = 4.7, 95% confidence interval [CI] 4.2–5.3), which was slightly lower than the risk of SMN in survivors of childhood cancer (SIR = 6.9, 95% CI 6.0–7.8). Risk for SMN was also compared by attained age and found to be lower for survivors of early-AYA relative to childhood cancer, although the risk for breast cancer did not differ between the groups (see Figure 8-3 [Suh et al., 2020]).

Importantly, as most SMN are not observed in the first 5 years following an early-AYA cancer diagnosis, they are often seen in survivors during their adult years. This observation underscores the importance of transitioning survivors of early-AYA cancer to Institute of Medicine and National Research Council–recommended risk-based health care (IOM and NRC, 2003) with cancer care providers who focus on high-risk SMN screening as recommended by the Children’s Oncology Group (COG),3 the American Cancer Society,4 and other international guideline groups (Mulder et al., 2013).

___________________

3 See www.survivorshipguidelines.org (accessed October 1, 2020).

4 See https://www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-survivorship-guidelines.html (accessed October 1, 2020).

CLINICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN ADOLESCENCE AND YOUNG ADULTHOOD

Advances in cure rates for AYAs diagnosed with their primary cancer between the ages of 15 and 39 years have developed at a slower pace than cure rates for younger children and older adults (Bleyer, 2002). Many factors have been identified as contributing to these disparate outcomes. They include delays in diagnosis and suboptimal access and accrual to clinical trials, as well as differences in tumor and host biology across different age groups.

AYA patients with cancer have the lowest rates of participation in clinical trials (Bleyer et al., 2018). Factors associated with these low rates of participation include a nonpediatric treatment setting, a treatment site at a nonacademic institution, and a physician without pediatric training (Tai et al., 2014).

Efforts to increase clinical trial participation rates have included adjusting the age of eligibility for COG trials and the development of AYA oncology programs that span the transition from pediatric to adult settings. Additionally, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has issued guidance to the pharmaceutical industry, clinical investigators, and institutional review boards to facilitate the inclusion of patients aged 12–17 in relevant adult oncology clinical trials (FDA, 2019). The Adolescent & Young Adult Health Outcomes & Patient Experience (AYA HOPE) study found that only 23 percent of patients diagnosed with cancer at ages 15–21 were treated by pediatric physicians (Parsons et al., 2015). Pediatric oncologists often utilize different staging and risk stratification criteria than those used by their adult colleagues. An example is Hodgkin lymphoma, for which there is no consistent risk stratification schema between adult and pediatric oncologists, with differences in such definitions as bulk disease. Studies comparing clinical trial outcomes for 17- to 21-year-old patients enrolled in adult and pediatric trials in ALL (Stock, 2010) and Hodgkin lymphoma (Henderson et al., 2018) have demonstrated superior outcomes for those treated in pediatric trials for ALL and for advanced-stage (stages III and IV) Hodgkin lymphoma.

Finally, protocols for chemotherapy and radiation therapy differ for pediatric and adult patients. Delays in diagnosis, differences in psychosocial supports, variable compliance with prescribed treatments, and dose delays and modifications have been suggested as additional factors contributing to disparate outcomes for AYAs diagnosed with cancer.

Following treatment, complexities at the point of transition between pediatric and adult care persist. Barriers to the transfer of AYA survivors to adult care include inadequate patient education, lack of providers skilled in the treatment of adult survivors of pediatric cancer, cognitive/emotional

delay, history of patient noncompliance, instability of the survivor’s medical situation, and health insurance issues (Kenney et al., 2017). Evidence indicates that the majority of AYA survivors receive care in the community from adult-oriented providers who may lack familiarity with survivorship guidelines, with less than one-third receiving survivor-focused care (Nathan et al., 2008).

LATE EFFECTS

Like all survivors of childhood cancer, those diagnosed with their cancer between the ages of 15 and 19 are at increased risk of late effects of their cancer and its therapies. Many of the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial late effects seen in survivors of childhood cancer across the childhood age spectrum are described in Chapter 4. These survivors have a more than fourfold risk of developing severe and disabling, life-threatening, or fatal chronic health conditions compared with siblings of the same age (hazard ratio [HR] = 4.2, 95% CI 3.7–4.8) (Suh et al., 2020). Early-AYA survivors have elevated risks of severe, life-threatening, or fatal cardiac (HR = 4.3, 95% CI 3.5–5.4), endocrine (HR = 3.9, 95% CI 2.9–5.1), and musculoskeletal (HR = 6.5, 95% CI 3.9–11.1) complications compared with siblings. AYA patients with cancer face distinct developmental challenges relative to younger patients with cancer. These challenges are due to diagnosis during a phase of development of values and identity in combination with a stage of physiologic development distinct from that of younger children with cancer, as discussed below. Because of these late effects, risk-based health care throughout the lifespan is recommended (COG, 2018; IOM and NRC, 2003). Unfortunately, data suggest that most survivors and their primary care providers are not compliant with guideline-based recommendations for screening for late effects (Nathan et al., 2008, 2013; Suh et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2020).

FERTILITY PRESERVATION

Patients aged 15–19 diagnosed with cancer may be concerned about fertility preservation. Guidelines for estimating the risk to future gonadal function and fertility posed by cancer and its therapy are available from the COG (2018), and fertility preservation should be considered for both males and females in the 15–19 age range. Males exposed to alkylator chemotherapy or pelvic radiotherapy are at highest risk for sterility.

Practice guidelines for fertility preservation in patients with cancer have been published by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) (Oktay et al., 2018). Options for mitigating risks to fertility differ based on pubertal status. Postpubertal males should be offered sperm preservation/

banking in advance of treatment initiation. Other techniques, including radiation shielding and nerve-sparing surgical approaches, may reduce future male fertility risks. Females exposed to alkylator chemotherapy or pelvic radiotherapy are at increased risk of premature menopause. Currently, there are several standard methods for preserving fertility in young women, including embryo and oocyte (egg) cryopreservation. Ovarian shielding or ovarian transposition surgery (oophoropexy), in which the ovaries are repositioned away from the radiation field before radiation treatment begins, may also reduce female infertility risks. Experimental procedures being studied include testicular and ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

FUNCTIONAL IMPACTS UNIQUE TO ADOLESCENCE AND YOUNG ADULTHOOD

The AYA period is important for two populations: those who are diagnosed with cancer in this age range and those who are diagnosed prior to this age range but are survivors during this period and subject to chronic and late effects. AYAs, both those with a diagnosis as an AYA and survivors of a childhood diagnosis, experience functional impacts distinct from those of children and adults. This section addresses functional considerations unique to this age group.

Psychosocial and Emotional Functioning

The available evidence on the impact of childhood cancer on the psychosocial and emotional development of AYA survivors is sufficiently strong that guidelines have been developed to guide follow-up care for these survivors, including care focused on their psychosocial and emotional functioning. Certain guidelines are applicable to all AYA survivors (e.g., the COG’s Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines, v.5; the ASCO’s Survivorship Care Compendium; guidelines of the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology; and the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer). Other guidelines are more specific to selected subgroups of these young survivors (e.g., the recommendations of the COG for survivors of childhood cell transplantation). All of these guidelines recommend an annual assessment of survivors’ psychosocial status, including emotional, educational/vocational, and social concerns (Chow et al., 2016; COG, 2018). Some studies indicate that emotional and quality-of-life scores for AYA survivors of childhood cancer are likely to be similar to those for age cohorts, but that 20–40 percent show concerning psychosocial and emotional differences from such comparison groups (Yi and Syrjala, 2020). This range of concerning rates may indicate that the subset of at-risk survivors younger than 18 years identified in Chapter 4 continues into the ages over 18 years. The psychosocial and emotional

needs of this young group of survivors are also reported to exceed those same needs in adult survivors of cancer (Yi and Syrjala, 2020).

Educational and Vocational Impact

In a recent literature review regarding the psychosocial needs of AYA survivors of cancer, an evidence-based conclusion is that educational achievement and employment are associated with reports of higher quality of life (Feuz, 2014). However, such achievements can be challenged by health-related absences from school and work. A recent systematic review of employment in young survivors of cancer includes 23 publications from eight countries (Stone et al., 2017). Findings indicate that survivors were significantly older than their age cohort when beginning a first job, although a majority were able to be employed and productive. Approximately one-quarter of the studied AYA survivors reported that cancer and its treatment made job-required physical tasks more difficult, and approximately 14 percent reported finding job-required mental tasks more difficult, a challenge to employment goals. Not being employed is linked to mental distress in several of the reviewed studies discussed below.

Emotional and Mental Health and Quality of Life

In a large study comparing AYA survivors of cancer (n = 4,054) with a same-age group that had not experienced cancer (n = 345,592), the cancer survivors reported poorer emotional health at twice the frequency of the comparison group (Tai et al., 2012). Smaller studies involving comparison groups have yielded similar findings (Cantrell and Posner, 2014; Husson et al., 2017; Kazak et al., 2010). Survivors diagnosed as adolescents have reported significantly higher anxiety and fewer positive health beliefs relative to survivors diagnosed at younger ages (Kazak et al., 2010), providing evidence for the existence of a subset of young survivors with greater adversities secondary to the cancer experience compared with younger counterparts. One conclusion from a systematic review of the impact of childhood cancer on AYA survivors is that close monitoring is needed to detect depression and/or distress (Stone et al., 2017). A limited number of small-scale interventions involving the use of metacognitive therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce anxiety and depression in AYA survivors have shown both short-term and sustained improvements (Bradford and Chan, 2017), a finding that indicates the need for larger-scale tests of such interventions.

Studies completed in the United States and in Nordic countries involving survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed before age 20 have shown higher rates of risky behaviors, including suicide and suicidal ideation, in

these survivors compared with age- and gender-matched control groups. Two separate studies by Recklitis and colleagues (2006, 2010) using patient-reported outcome measures found higher rates of suicidality in survivors compared with siblings or other control groups. The higher rates of suicidality were not found to be related to age, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, gender, or global health ratings, but to current poor physical health and functioning and pain. Similarly, a three-country study involving national registries compared cause of death in survivors diagnosed prior to age 20 and in nonsurvivors matched for age, sex, and country. This study found that the risk of dying secondary to a risk behavior—specifically suicide—was significantly higher in survivors. Risk factors included diagnosis of a central nervous system (CNS) tumor and diagnosis at particular ages (5–9 years and 15–19 years) (Korhonen et al., 2019).

Sexual Development

In a review of the impact of the cancer experience on AYAs, Yi and Syrjala (2020) describe studies finding sexual functioning problems in survivors that exceeded those reported by their age peers who had not experienced cancer. Female survivors reported a greater frequency of sexual functioning problems, while males reported higher distress secondary to their sexual functioning problems.

Cognitive Functioning

As reviewed in Chapter 4, cognitive sequelae are common in survivors of childhood cancer (Krull et al., 2018; Phillips et al., 2015), with up to 35 percent of survivors of any childhood cancer exhibiting cognitive deficits (Phillips et al., 2015). This frequency increases to 40–100 percent in survivors of CNS cancers or CNS-directed therapies (Correa, 2010; Glauser and Packer, 1991; Krull et al., 2013). The timing of the development of these problems can vary greatly, from acutely at the time of diagnosis, to immediately following initiation of treatment, to delayed following completion of treatment and some recovery. More important, there is strong evidence that these cognitive sequelae persist, sometimes progress, and inevitably affect functioning throughout a survivor’s lifetime (Harila et al., 2009; Maddrey et al., 2005). Given the likelihood of persistence and possibility of progression, it is essential that survivors undergo repeated cognitive evaluations, particularly as they progress through adolescence and into young adulthood, when functional expectations of independence are increased (Nathan et al., 2007). It is during these critical maturational time periods that underlying cognitive deficits may result in significant adaptive

functional impairment that may have not been evident previously (Netson et al., 2012, 2013; Papazoglou et al., 2008). For example, deficits in executive functioning in survivors of childhood cancer are associated with significant academic underachievement and poor employment outcomes in adulthood (Brinkman et al., 2016). These persistent cognitive impairments can impact all of SSA’s functional equivalence domains: acquiring and using information, attending and completing tasks, interacting and relating with others, moving about and manipulating objects, caring for oneself, and health and physical well-being.

Although studied less frequently and less thoroughly, the occurrence of cognitive sequelae is also evident in individuals who are diagnosed with cancer during the AYA time period (Jim et al., 2018; Krull et al., 2018). However, the few studies of AYA patients with cancer show evidence of some degree of cognitive dysfunction (John et al., 2016). In fact, individuals diagnosed in this time period may exhibit the functional disability effects of cognitive symptoms more quickly relative to those diagnosed at younger ages because of the greater demands and expectations for independence mentioned above. Although the discrepancy in skills may be small initially, the impact of even mild deficits in such areas as executive functioning in AYA survivors can be significant (Nugent et al., 2018). As noted above, it is well documented that the educational attainment and vocational outcomes of survivors of childhood cancer are well below those of typically developing same-age peers (Jacola et al., 2016).

As stated in Chapter 4, determination of intellectual disability is no longer based primarily on formal intellectual scores but also on assessment of an individual’s capacity to complete activities of daily living in an independent manner. Therefore, as deficits in adaptive functioning become evident in the AYA time period, it is important to consider survivors’ need for guardianship, providing continued assistance and supervision.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Findings

8-1 Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer are a population with inferior outcomes relative to both younger children and older adults for multifactorial reasons and with impacts on functioning in this transitional life stage.

8-2 Adolescents who are being reconsidered for U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) disability benefits upon turning age 18 must navigate the transition between the child determination

process that incorporates functional equivalence to peers and the adult process that focuses on medical–vocational evaluations.

8-3 Complexities in the transition from pediatric to adult cancer care and follow-up may lead to patients’ disengagement in care, which in turn can result in more severe adverse outcomes in adult survivors of childhood cancers.

8-4 Attrition at the point of transfer from pediatric to adult cancer care cannot be explained solely by issues of access.

8-5 Survivors report physical, cognitive, and psychosocial challenges to achieving employment goals; the proportion impacted varies substantially based on diagnosis and treatment.

8-6 Almost half of the survivors of AYA cancers are unable to attain educational achievements similar to those of their peers, and to do so may take them longer or require modification or support.

8-7 Interventions to support educational, vocational, social, and emotional functioning in these survivors are limited to small-scale behavioral interventions that, although promising, have evaluation periods too limited to determine whether improvements are sustained.

8-8 Survivors of AYA cancers are at higher risk of anxiety, depression, and distress compared with age cohorts who have not experienced cancer.

8-9 Current guidelines recommend annual assessments to detect late effects, subsequent cancers, and emotional distress in these young survivors, as well as periodic neuropsychological assessments.

8-10 Given expectations of independence within the AYA developmental period, even a mild change in cognitive and adaptive skills can have a significant impact on the functional capacity of survivors of childhood and AYA cancers.

8-11 Despite regulatory and institutional changes to increase access, participation in clinical trials remains limited for AYAs.

Conclusions

8-1 The change in SSA’s determination process for children and adults introduces challenges for establishing/sustaining disability benefits across the 18-year-old threshold.

8-2 Special support is required to keep survivors of childhood and AYA cancers engaged in the health care system into and through adulthood to detect and manage late effects.

REFERENCES

Bleyer, A., E. Tai, and S. Siegel. 2018. Role of clinical trials in survival progress of American adolescents and young adults with cancer—and lack thereof. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 65(8):e27074.

Bleyer, W. A. 2002. Cancer in older adolescents and young adults: Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, survival, and importance of clinical trials. Medical and Pediatric Oncology: The Official Journal of SIOP—International Society of Pediatric Oncology (Societé Internationale d’Oncologie Pédiatrique) 38(1):1–10.

Bradford, N. K., and R. J. Chan. 2017. Health promotion and psychological interventions for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Cancer Treatment Reviews 55:57–70.

Bright, C. J., R. C. Reulen, D. L. Winter, D. P. Stark, M. G. McCabe, A. B. Edgar, C. Frobisher, and M. M. Hawkins. 2019 Risk of subsequent primary neoplasms in survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer (Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Survivor Study): A population-based, cohort study. The Lancet Oncology 20(4):531–545.

Brinkman, T. M., M. J. Krasin, W. Liu, G. T. Armstrong, R. P. Ojha, Z. S. Sadighi, P. Gupta, C. Kimberg, D. Srivastava, T. E. Merchant, A. Gajjar, L. L. Robison, M. M. Hudson, and K. R. Krull. 2016. Long-term neurocognitive functioning and social attainment in adult survivors of pediatric CNS tumors: Results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 34(12):1358–1367.

Cantrell, M. A., and M. A. Posner. 2014. Psychological distress between young adult female survivors of childhood cancer and matched female cohorts surveyed in the adolescent health study. Cancer Nursing 37(4):271–277.

COG (Children’s Oncology Group). 2018. Long-Term Follow-up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers. Version 5. Monrovia, CA: Children’s Oncology Group. www.survivorshipguidelines.org (accessed April 12, 2020).

Chow, E. J., L. Anderson, K. Scott Baker, S. Bhatia, G. M. T. Guilcher, J. T. Huang, W. Pelletier, J. L. Perkins, L. S. Rivard, T. Schechter, A. J. Shah, K. D. Wilson, K. Wong, S. S. Grewal, S. H. Armenian, L. R. Meacham, D. A. Mulrooney, and S. M. Castellino. 2016. Late effects surveillance recommendations among survivors of childhood hematopoietic cell transplantation: A children’s oncology group report. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 22(5):782–795.

Correa, D. D. 2010. Neurocognitive function in brain tumors. Current Neurology & Neuroscience Reports 10(3):232–239.

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2019. Considerations for the Inclusion of Adolescent Patients in Adult Oncology Clinical Trials Guidance for Industry. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/media/113499/download (accessed June 23, 2020).

Feuz, C. 2014. Are current care models meeting the psychosocial needs of adolescents and young adult cancer survivors? A literature review. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences 45:119–130.

Glauser, T. A., and R. J. Packer. 1991. Cognitive deficits in long-term survivors of childhood brain tumors. Child’s Nervous System 7(1):2–12.

Harila, M. J., S. Winqvist, M. Lanning, R. Bloigu, and A. H. Harila-Saari. 2009. Progressive neurocognitive impairment in young adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 53(2):156–161.

Henderson, T. O., S. K. Parsons, K. E. Wroblewski, L. Chen, F. Hong, S. M. Smith, J. L. McNeer, R. H. Advani, R. D. Gascoyne, L. S. Constine, S. Horning, N. L. Bartlett, B. Shah, J. M. Connors, J. I. Leonard, B. S. Kahl, K. M. Kelly, C. L. Schwartz, H. Li, J. W. Fried-berg, D. L. Friedman, L. I. Gordon, and A. M. Evens. 2018. Outcomes in adolescents and young adults with Hodgkin lymphoma treated on U.S. cooperative group protocols: An adult intergroup (E2496) and Children’s Oncology Group (COG AHOD0031) comparative analysis. Cancer 124(1):136–144.

Howlader, N., A. M. Noone, M. Krapcho, D. Miller, A. Brest, M. Yu, J. Ruhl, Z. Tatalovich, A. Mariotto, D. R. Lewis, H. S. Chen, E. J. Feuer, and K. A. Cronin, eds. 2019. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2016. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016 (accessed May 6, 2020).

Husson, O., J. B. Prins, S. E. Kaal, S. Oerlemans, W. B. Stevens, B. Zebrack, W. T. A. van der Graaf, and L. V. van de Poll-Franse. 2017. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) lymphoma survivors report lower health-related quality of life compared to a normative population: Results from the PROFILES registry. Acta Oncologica 56(2):288–294.

IOM and NRC (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council). 2003. Childhood cancer survivorship: Improving care and quality of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jacola, L. M., K. Edelstein, W. Liu, C. Pui, R. Hayashi, N. S. Kadan-Lottick, D. Srivastava, T. Henderson, W. Leisenring, L. L. Robison, G. T. Armstrong, and K. R. Krull. 2016. Cognitive, behavior, and academic functioning in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. The Lancet Psychiatry 3(10):965–972.

Jim, H. S. L., S. L. Jennewein, G. P. Quinn, D. R. Reed, and B. J. Small. 2018. Cognition in adolescent and young adults diagnosed with cancer: An understudied problem. Journal of Clinical Oncology 36(27):2752–2754.

John, T. D., L. S. Sender, and D. A. Bota. 2016. Cognitive impairment in survivors of adolescent and early young adult onset non-CNS cancers: Does chemotherapy play a role? Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology 5(3):226–231.

Kazak, A. E., B. W. DeRosa, L. A. Schwartz, W. Hobbie, C. Carlson, R. F. Ittenbach, J. J. Mao, and J. P. Ginsberg. 2010. Psychological outcomes and health beliefs in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer and controls. Journal of Clinical Oncology 28(12):2002–2007.

Kenney, L. B., P. Melvin, L. N. Fishman, J. O’Sullivan Oliveira, G. S. Sawicki, S. Ziniel, L. Diller, and S. M. Fernandes. 2017. Transition and transfer of childhood cancer survivors to adult care: A national survey of pediatric oncologists. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 64(2):346–352.

Korhonen, L. M., M. Taskinen, M. Rantanen, F. Erdmann, J. F. Winther, A. Bautz, M. Feychting, H. Moegnsen, M. Talback, N. Malila, H. Ryynanen, and L. Madanet-Harjuoja. 2019. Suicides and deaths linked to risky health behavior in childhood cancer patients: A Nordic population-based register study. Cancer 125(20):3631–3638.

Krull, K. R., T. M. Brinkman, C. Li, G. T. Armstrong, K. K. Ness, D. K. Srivastava, and M. M. Hudson. 2013. Neurocognitive outcomes decades after treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 31(35):4407–4415.

Krull, K. R., K. K. Hardy, L. S. Kahalley, I. Schuitema, and S. R. Kesler. 2018. Neurocognitive outcomes and interventions in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 36(21):2181–2189.

Maddrey, A. M., J. A. Bergeron, E. R. Lombardo, N. K. McDonald, A. F. Mulne, P. D. Barenberg, and D. C. Bowers. 2005. Neuropsychological performance and quality of life of 10 year survivors of childhood medulloblastoma. Journal of Neuro-Oncology 72(3):245–253.

Mulder, R. L., L. C. M. Kremer, M. M. Hudson, S. Bhatia, W. Landier, G. Levitt, L. S. Constine, W. H. Wallace, F. E. van Leeuwen, C. M. Ronckers, T. O. Henderson, M. Dwyer, R. Skinner, and K. C. Oeffinger. 2013. Recommendations for breast cancer surveillance for female survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer given chest radiation: A report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. The Lancet Oncology 14(13):e621–e629.

Nathan, P. C., S. K. Patel, K. Dilley, R. Goldsby, J. Harvey, C. Jacobsen, N. Kadan-Lottick, K. McKinley, A. K. Millham, I. Moore, M. F. Okcu, C. L Woodman, P. Brouwers, F. D. Armstrong, Children’s Oncology Group Long-term Follow-up Guidelines Task Force on Neurocognitive/Behavioral Complications After Childhood Cancer. 2007. Guidelines for identification of, advocacy for, and intervention in neurocognitive problems in survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 161(8):798–806.

Nathan, P. C., M. L. Greenberg, K. K. Ness, M. M. Hudson, A. C. Mertens, M. C. Mahoney, J. G. Gurney, S. S. Donaldson, W. M. Leisenring, L. L. Robison, and K. C. Oeffinger. 2008. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 26(27):4401.

Nathan, P. C., C. K. Daugherty, K. E. Wroblewski, M. L. Kigin, T. V. Stewart, F. J. Hlubocky, E. Grunfeld, D. Giudice, L.-A. E. Ward, J. M. Galliher, K. C. Oeffinger, and T. O. Henderson. 2013. Family physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 7(3):275–282.

Netson, K. L., H. M. Conklin, S. Wu, X. Xiong, and T. E. Merchant. 2012. A 5-year investigation of children’s adaptive functioning following conformal radiation therapy for localized ependymoma. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics 84(1):217–223.

Netson, K. L., H. M. Conklin, S. Wu, X. Xiong, and T. E. Merchant. 2013. Longitudinal investigation of adaptive functioning following conformal irradiation for pediatric craniopharyngioma and low-grade glioma. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics 85(5):1301–1306.

Nugent, B. D., C. M. Bender, S. M. Sereika, J. M. Tersak, and M. Rosenzweig. 2018. Cognitive and occupational function in survivors of adolescent cancer. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology 7(1):79–87.

Oktay, K., B. E. Harvey, A. H. Partridge, G. P. Quinn, J. Reinecke, H. S. Taylor, W. H. Wallace, E. T. Wang, and A. W. Loren. 2018. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology 36(19):1994–2001.

Papazoglou, A., T. Z. King, R. D. Morris, and N. S. Krawiecki. 2008. Cognitive predictors of adaptive functioning vary according to pediatric brain tumor location. Developmental Neuropsychology 33(4):505–520.

Parsons, H. M., L. C. Harlan, S. Schmidt, T. H. M. Keegan, C. F. Lynch, E. E. Kent, X. C. Wu, S. M. Schwartz, R. L. Chu, G. Keel, and A. W. Smith. 2015. Who treats adolescents and young adults with cancer? A report from the AYA HOPE Study. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology 4(3):141–150.

Phillips, S. M., L. S. Padgett, W. M. Leisenring, K. K. Stratton, K. Bishop, K. R. Krull, C. M. Alfano, T. M. Gibson, J. S. de Moor, D. B. Hartigan, G. T. Armstrong, L. L. Robison, J. H. Rowland, K. C. Oeffinger, and A. B. Mariotto. 2015. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: Prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 24(4):653–663.

Recklitis, C. J., R. A. Lockwood, M. A. Rothwell, and L. R. Diller. 2006. Suicidal ideation and attempts in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 24(24):3852–3857.

Recklitis, C. J., L. R. Diller, X. Li, J. Najita, L. L. Robison, and L. Zeltzer. 2010. Suicide ideation in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 28(4):655.

SSA (U.S. Social Security Administration). 2010. POMS DI 24505.001: Individual must have a medically determinable severe impairment. https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0424505001 (accessed April 3, 2019).

SSA. 2020a. Disability evaluation under social security. https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/general-info.htm (accessed March 20, 2020).

SSA. 2020b. Listing of impairments—Childhood listings (part B). https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/ChildhoodListings.htm (accessed January 13, 2020).

SSA. 2020c. Substantial gainful activity. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/sga.html (accessed April 3, 2020).

SSA. 2020d. What you need to know about your supplemental security income (SSI) when you turn 18. https://www.ssa.gov/pubs/EN-05-11005.pdf (accessed May 20, 2020).

Stock, W. 2010. Adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. American Society of Hematology Education Program Book 2010 1:21–29.

Stone, D. S., P. A. Ganz, C. Pavlish, and W. A. Robbins. 2017. Young adult cancer survivors and work: A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 11(6):765–781.

Suh, E., C. K. Daugherty, K. Wroblewski, H. Lee, M. L. Kigin, K. A. Rasinski, J. S. Ford, E. S. Tonorezos, P. C. Nathan, K. C. Oeffinger, and T. O. Henderson. 2014. General internists’ preferences and knowledge about the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer: A cross-sectional survey. Annals of Internal Medicine 160(1):11–17.

Suh, E., K. L Stratton, W. M Leisenring, P. C. Nathan, J. S. Ford, D. R Freyer, J. L McNeer, W. Stock, M. Stovall, K. R. Krull, C. A. Sklar, J. P. Neglia, G. T. Armstrong, K. C. Oeffinger, L. L. Robison, and T. O. Henderson. 2020. Late mortality and chronic health conditions in long-term survivors of early-adolescent and young adult cancers: A retrospective cohort analysis from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. The Lancet Oncology 21(3):421–435.

Tai, E., N. Buchanan, J. Townsend, T. Fairley, A. Moore, and L. C. Richardson. 2012. Health status of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer 118(19):4884–4891.

Tai, E., N. Buchanan, L. Westervelt, D. Elimam, and S. Lawvere. 2014. Treatment setting, clinical trial enrollment, and subsequent outcomes among adolescents with cancer: A literature review. Pediatrics 133(3):S91–S97.

Yan, A. P., Y. Chen, T. O. Henderson, K. C. Oeffinger, M. M. Hudson, T. M. Gibson, J. P. Neglia, W. M. Leisenring, K. K. Ness, J. S. Ford, L. L. Robison, G. T. Armstrong, Y. Yasui, and P. C. Nathan. 2020. Adherence to surveillance for second malignant neoplasms and cardiac dysfunction in childhood cancer survivors: A childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 38(15):1711–1722.

Yi, J. C., and K. L. Syrjala. 2020. Overview of cancer survivorship in adolescent and young adults. Uptodate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cancer-survivorship-in-adolescent-and-young-adults (accessed April 11, 2020).

This page intentionally left blank.