1

Introduction

The period of gestation is one of the most important predictors of an infant’s subsequent health and survival. In 2004, more than 500,000 infants, or 12.5 percent of all infants, were born preterm, which is considered birth at less than 37 completed weeks of gestation (CDC, 2005a). On the basis of new estimates provided in this report, the annual societal economic burden associated with preterm birth in the United States was in excess of $26.2 billion in 2005 (this estimate represents a lower boundary).

The percentage of preterm deliveries has risen steadily over the last 2 decades. Most of this increase has been among children born at 32 to 36 weeks gestation. In the past, low birth weight has been used as an indicator for preterm birth; however, the present Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee considers low birth weight to be a poor surrogate and has specifically focused its analysis on preterm birth.

Compared with infants born at term (37 to 41 weeks of gestation), preterm infants have a much greater risk of death and disability. Approximately 75 percent of perinatal deaths occur among preterm infants (Slattery and Morrison, 2002). Almost one-fifth of all infants born at less than 32 weeks gestation do not survive the first year of life, whereas about 1 percent of infants born at between 32 and 36 weeks of gestation and 0.3 percent of infants born at 37 to 41 weeks of gestation do not survive the first year of life. The infant mortality rate (IMR) per 1,000 live births for infants born at less than 32 weeks of gestation was 180.9, nearly 70 times the rate for infants born at between 37 and 41 weeks of gestation (Mathews et al., 2002).

Advances in medical technologies and therapeutic perinatal and neo

natal care have led to improved rates of survival among preterm infants, including those born when they are as young as a gestational age of 23 weeks. However, surviving infants have a higher risk of morbidity. Neuro-developmental disabilities can range from major disabilities such as cerebral palsy, mental retardation, and sensory impairments to more subtle disorders, including language and learning problems, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and behavioral and social-emotional difficulties. Preterm infants are also at increased risk for growth and health problems, such as asthma or reactive airway disease (see Chapter 11 for review).

Although significant improvements in treating preterm infants and improving survival have been made, little success in understanding and preventing preterm birth has been attained. The complexity of factors that are involved in preterm birth will require a multidisciplinary approach to research directed at understanding its etiologies, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatments. However, there are barriers to the recruitment and participation of scientists in these investigations. A critical barrier to research is the demand on clinical researchers in academic centers to provide clinical income and other duties that take them away from research. This necessitates the development of new ways to provide support to allow the time to conduct this important research.

The challenge for researchers and clinicians remains to identify interventions that prevent preterm birth; reduce the morbidity and mortality of the mother or the infant, or both, once preterm birth occurs; and reduce the incidence of long-term disability in children in the most comprehensive and cost-effective manner possible.

CONTEXT AND CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

The persistent and troubling problem of preterm birth prompted IOM to convene a committee to assess the current state of the science on the causes and broad consequences of preterm birth. This interest was generated by the IOM Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Research, and Medicine, which convened a workshop in October 2001 focused on the role of the environment in preterm birth. In 2003, the Roundtable published a factual summary of this workshop in The Role of Environmental Hazards in Premature Birth (IOM, 2003). The Roundtable members, concerned that research into understanding preterm birth was not progressing as fast as was hoped, believed that progress could be made if researchers had an agenda to follow, an agenda that would help focus and direct research efforts for the variety of disciplines needed to address this problem.

With assistance from the study sponsors, the Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes was established. The sponsors include the National Institute of Child Health and Human

Development, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the March of Dimes, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Specifically, the charge presented to the committee of 17 members was as follows:

An IOM committee will define and address the health related and economic consequences of premature birth. The broad goals are to (1) describe the current state of the science and clinical research with respect to the causes of premature birth; (2) address the broad costs—economic, medical, social, psychological, and educational—for children and their families; and (3) establish a framework for action in addressing the range of priority issues, including a research and policy agenda for the future. In support of these broad goals, the study will:

-

Review and assess the various factors contributing to the growing incidence of premature birth, which may include the trend to delay childbearing and racial and ethnic disparities;

-

Assess the economic costs and other societal burdens associated with premature births;

-

Address research gaps/needs and priorities for defining the mechanisms by which biological and environmental factors influence premature birth; and

-

Explore possible changes in public health policy and other policies that may benefit from more research.

In order to assess research gaps and needs, the committee will plan an additional meeting that will address barriers to clinical research in the area of preterm birth. A workshop hosted by the committee will seek to

-

Identify major obstacles to conducting clinical research, which may include the declining number of residents interested in entering the field of obstetrics and gynecology and the resulting effect on the pipeline of clinical researchers; the impact of rising medical malpractice premiums on the ability of academic programs to provide protected time for physicians to pursue research; and ethical and legal issues in conducting research on pregnant women (for example, the consideration of safety issues and informed consent); and

-

Provide strategies for removing barriers—including those targeting resident career choices, departments of obstetrics and gynecology, agencies and organizations that fund research, and professional organizations.

During the 21-month study, the committee convened for six meetings and hosted three public workshops (see Appendix A for the study methods).

PREVIOUS REPORTS ADDRESSING PRETERM BIRTH AND LOW BIRTH WEIGHT INFANTS

Several reports on the problem of preterm birth, low birth weight, and other infant outcomes have been published by the Institute of Medicine, in addition to the workshop summary on The Role of Environmental Hazards in Premature Birth. Preventing Low Birthweight (IOM, 1985) defined the significance of the problem of low birth weight, reviewed data on risk factors and etiology, and examined state and national trends in the incidence of low birth weight among various groups. This report also described approaches to prevent low birth weight and their economic costs and identified research needs. Prenatal Care: Reaching Mothers, Reaching Infants (IOM, 1988) examined 30 prenatal care programs, analyzed surveys of mothers who did not seek prenatal care, and made recommendations for improving the nation’s maternity system and increasing the use of prenatal care programs. Two recent reports: Reducing Birth Defects: Meeting the Challenges in the Developing World (IOM, 2003) and Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenges in the Developing World (IOM, 2003) address issues specific to developing countries.

Two IOM reports are specifically related to the committee’s charge to address research barriers; Medical Professional Liability and the Delivery of Obstetrical Care (IOM, 1989) and Strengthening Research in Academic OB/GYN Departments (IOM, 1992). The first report addressed medical liability and its effect on access to and delivery of obstetrical care; and civil justice and insurance systems, medical liability issues, and their combined effect on health care for mothers and children. The second report examined the ability of departments of obstetrics and gynecology to conduct research within academic departments in order to improve women’s health and the outcomes of pregnancy.

Research and other activities addressing preterm birth are also being conducted and supported by a variety of federal agencies and private foundations (see Chapter 13 for review). A major effort has been undertaken by the March of Dimes to address the problem of preterm birth. In January 2003, the Foundation launched its Prematurity Campaign to raise awareness of the problem of prematurity and reduce the rate of premature births. Components of the campaign include funding research, providing support to families affected by prematurity, working for access to insurance and health care coverage, helping providers learn ways to help reduce the risk for preterm delivery, and educating women about how to reduce their risk and recognize symptoms of preterm labor. The March of Dimes recently published a research agenda for preterm birth (Green et al., 2005). Major recommendations outlined six primary research topics including epidemiologic studies, genes and gene-environment interactions, racial-ethnic dis-

parities, role of inflammatory responses, stress responses and preterm birth, and clinical trials.

Other reports have also highlighted knowledge gaps and identified research priorities. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Perinatal Pediatrics convened a workshop in 2004 focusing on research in neonatology. The published summary of this workshop (Raju et al., 2005) identifies research opportunities in neuroscience, cardiopulmonary research, fetal and neonatal nutrition, gastrointestinal research, perinatal epidemiology, and neonatal pharmacology. Similarly, a workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention focused on follow-up care of high risk infants. The publication from this workshop (Vohr, 2004) provided suggestions to improve the long-term follow-up of this population. Suggestions included measuring the long-term impact of interventions for populations enrolled in randomized-controlled trials. Challenges were identified for multicenter networks, including standardizing study materials, achieving adequate follow-up rates, defining the study population and the timing of enrollment, and engaging a cost-effective and appropriate control population.

The current report makes a novel contribution by recommending directions for action and an organizational structure that will help focus research and policy directives on a variety of dimensions of preterm birth, based on a comprehensive assessment of the status of knowledge and scientific research regarding the causes and the broad short- and long-term consequences of preterm birth. In completing its task, the committee does not, however, provide an exhaustive review of the literature examining the various etiologies of preterm birth or its consequences for infants and children. Rather, the goal of this report is to summarize and synthesize this literature and to evaluate it to identify the gaps in knowledge and recommend a research agenda to address these gaps. The committee’s recommendations are based on scientific evidence and expert judgment.

The findings and recommendations of this report are intended to assist policy makers, academic researchers, funding agencies and organizations, third party payors, and health care professionals in prioritizing research and to inform the public about the problem of preterm birth. The ultimate goal of the committee’s efforts is to work toward improved outcomes for children who have been born preterm and their families.

RECURRING THEMES

At the beginning of its deliberations, the committee noticed three topics that repeatedly emerged. These topics became themes that helped to orga-

nize the committee’s thinking and approach to the issue of preterm birth. The first was a need for clarity in terms. The population of preterm infants is diverse, with preterm births having various etiologies and infants born preterm having various complications and outcomes. A variety of terms have been used to characterize the duration of gestation, fetal growth, and maturation. These terms have been inconsistently applied and used interchangeably in the literature. The inconsistent use of terms has made it difficult to interpret the data on the causes and consequences of preterm birth and to evaluate the appropriate treatments for children who are born preterm. Early on in its deliberations, the committee decided to use the term preterm birth, which is based on the period of gestation, to assess this population of infants (Chapter 2 provides a discussion of terminology used in the literature and various methods of determining gestational age). Although low birth weight is more often used as an outcome than preterm birth, the committee considers low birth weight to be a poor proxy. However, it recognizes that the preponderance of the evidence in this field has used low birth weight to identify the infants under study. The committee also recognizes the limitations of the various methods used to estimate gestational age (Chapter 2). The evidence contained in this report therefore draws first on the literature that uses gestational age, preterm birth, and small for gestational age as outcomes. In the absence of these outcomes, low birth weight and other related outcomes are cited as needed.

The committee also discussed the need to distinguish spontaneous preterm birth (which occurs naturally as a result of preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of fetal membranes) and indicated preterm birth (in which labor is initiated by medical intervention because of dangerous pregnancy complications). There has been a tendency to group births that occur as a result of these complications together, although the etiologies and the initiators of these types of birth may be quite distinct. When the data allow, the committee distinguishes spontaneous and indicated preterm births in its review of the evidence.

The second theme that guided the committee’s approach to its task was the troubling evidence of long-standing disparities in the rates of preterm birth among different subpopulations of the overall U.S. population. There is a greater risk and a higher proportion of preterm births among certain racial-ethnic, and socioeconomically disadvantaged sub-populations. Several explanations for this long-standing trend have been cited, including racial differences in genetics, cigarette smoking, substance use or abuse, work and physical activity, maternal behaviors, stress, institutional racism, access to and the use of prenatal care, and infections. The committee reviews these proposed explanations and discusses the need for a more integrative approach to understanding racial-ethnic and socioeco-

nomic disparities in preterm birth. Research needs in the area of the disparities are also discussed.

Third, the committee highlights the complexity of the problem that it was charged to assess. Preterm birth is not one disease for which there is likely to be one solution or cure. Rather, the committee considers preterm birth to be a cluster of problems that comprise a set of overlapping factors of influence that are interrelated. Its causes are multiple and may vary for different populations. Individual psychosocial and behavioral factors, neighborhood social characteristics, environmental exposures, medical conditions, assisted reproductive technology (ART), biological factors, and genetics may play roles to various degrees. Many of these factors co-occur, particularly in those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged or members of minority populations. It is difficult to assess the extent to which each potential factor accounts for the proportion of preterm births. This complexity makes the detection of solutions to the problem difficult. There will be no silver bullet.

The complex nature of preterm birth led the committee to consider its multiple causes in an integrated manner. Several perspectives provided background for the committee’s framing of this problem. New Horizons in Health: An Integrative Approach called for a need to focus on “multiple pathways to diverse health outcomes” (NRC, 2001, p. 2). It emphasized that for a more complete understanding of disease etiology, these pathways should incorporate information from the molecular and cellular levels into information from the psychosocial and community levels. Furthermore, the report states that “mechanisms underlying racial, ethnic, and social inequalities in health … cannot be fully understood without integrated pathway characterizations” (p. 2).

Understanding that multiple determinants across the life span need to be considered in the examination of perinatal health outcomes, Misra and colleagues (2003) proposed a framework, adapted from the Evans and Stoddart (1990) health field model, that incorporates distal factors (such as the genetic, physical, and social environments) that affect an individual’s predisposition or exposure and proximal factors (including biomedical and behavioral responses) that have a direct impact on an individual’s health. These risk factors are connected to a woman’s life course through the transition from preconception and interconception to the pregnancy. Lu and Halfon (2003) also called for a reexamination of the racial and ethnic disparities from a similar integrated life-course perspective. These views guided the committee’s approach to examining the causes of preterm birth, which include not only individual demographic, psychosocial, and behavioral factors but also broader social factors, medical and pregnancy conditions, biological pathways, gene-environment interactions, and environmental toxicants.

THE PROBLEM OF PRETERM BIRTH

With the proportion of preterm births reaching 12.5 percent of all births in the United States in 2004, the prevalence of preterm birth constitutes a public health problem. There are three primary reasons for this concern (Mattison et al., 2001). First, unlike many health problems, there has been a troubling increase in the rates of preterm birth in the past decade. Second, the birth of a preterm infant brings significant emotional and economic costs to families and communities. Third, there are notable disparities in the rates of preterm births across populations in the United States, and this disparity is particularly striking between African American women and Asian women. It is clear that the prevention of preterm birth is crucial to improving pregnancy outcomes.

This introduction provides an overview of these issues. First, major trends in preterm birth; that is, the rates or proportions of preterm births by gestational age at birth, geographic location, and maternal age and preterm births resulting from ARTs, are reviewed. Second, the broad costs of preterm birth are briefly described. Outcomes—including the health of the infant born preterm, the consequences of preterm birth on daily functioning, its impact on families, and the economic costs—are discussed in detail in later sections of the report. Last, evidence regarding the presence of disparities in the rates of preterm birth is introduced. As discussed above, this issue served as a broad theme that guided the committee’s approach to its task. Potential explanations for these disparities are discussed throughout the report.

Trends in Preterm Birth

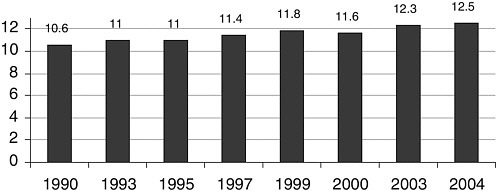

As many reports have indicated, the proportion of preterm births has risen fairly steadily since 1990 (Figure 1-1). Note, however, that some of the change in the rate of preterm birth is likely reflective of changes in the way in which gestational age is measured (see Chapter 2 for a discussion). In the early to mid-1990s the percentage of preterm births remained stable at about 11 percent. There was a slight decline from 11.8 percent in 1999 to 11.6 percent in 2000. In 2004, the percentage rose to its highest level since 1990, from 10.6 to 12.5 percent. Since 1981 (when the percentage was 9.4 percent), the proportion has increased more than 30 percent (CDC, 2005a).

Gestational Age

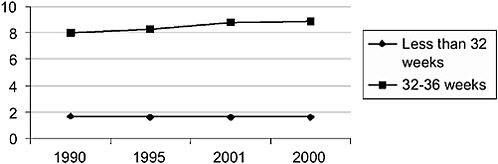

Changes in the distribution of preterm births by degree of prematurity have occurred over time. Although the group of infants with the greatest morbidity and mortality are those who are born at less than 32 weeks, infants born at between 32 and 36 weeks represent the greatest number of preterm births. Figure 1-2 illustrates that between 1990 and 2000, the per-

FIGURE 1-1 Preterm births as a percentage of live births in the United States, 1990 to 2004.

SOURCES: CDC (2001, 2002a, 2004a, 2005a).

FIGURE 1-2 Preterm births as a percentage of live births by gestational age.

SOURCE: CDC (2002a).

centage of preterm birth was the highest for infants born at between 32 and 36 weeks of gestation. Among singleton births, the 7 percent rise in preterm births between 1990 and 2002 was attributable to the birth of infants of these gestational ages (CDC, 2005a). In contrast, during the same time period the proportions of preterm births occurring at less than 32 weeks of gestation declined from 1.69 to 1.57 percent. (See Appendix B for further discussion of gestational age distribution and trends by race and ethnicity.)

Mortality Associated with Preterm Birth

The overall Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) decreased from 9.1 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 6.9 in 2000. An interruption in this steady

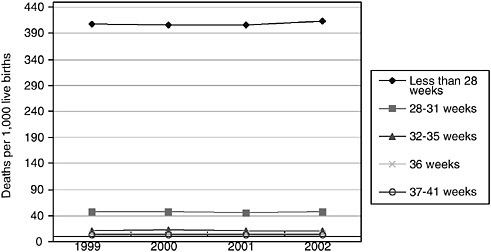

FIGURE 1-3 IMRs by gestational age, United States, 1999 to 2002.

SOURCE: CDC (2005c).

decline was evidenced in 2002, with an increase in the IMR to 7.0 deaths from 6.8 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2001, the first rise since 1958 (CDC, 2003a, 2005e). Analyses assessing the relative contribution of the change in the distribution of births by gestational age and in gestational age-specific IMRs to the change in the IMR revealed that 61 percent of the rise in the IMR from 2001 to 2002 was due to changes in the distribution of births by gestational age. Thirty-nine percent of the increase was due to changes in gestational age-specific mortality rates (CDC, 2005c,d).

In 2002, the IMR for infants born at less than 37 completed weeks of gestation was 37.9 deaths per 1,000 live births, whereas the IMR was 2.5 deaths per 1,000 live births for infants born at between 37 and 41 weeks of gestation (full term). Figure 1-3 displays IMRs by gestational age from 1999 to 2002. In 2002, approximately 64 percent of all infant deaths were for the 12.1 percent of infants who were born at less than 37 weeks of gestation and 53.7 percent of all infant deaths were for the 2 percent of infants born at less than 32 weeks of gestation. (Also see Appendix B for data reflecting gestational age-specific IMRs and geographic variations in mortality rates.)

Geographic Differences

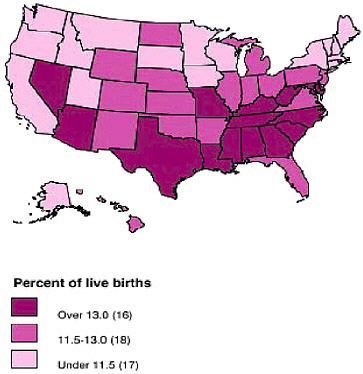

The proportion of preterm births varies considerably across different regions of the country (Figure 1-4). This variation may be related to state demographics, such as the distribution of maternal ages, multiple births, and race and ethnicity (CDC, 2005b). In 2003, the lowest percentages were

FIGURE 1-4 Percentage of preterm births by U.S. state, 2003.

SOURCE: MOD (2005d).

in the Northeast states (particularly New England), followed by the West, the Midwest, and the South. It is notable that within the western region of the country, where many states have proportions of preterm birth below the national average, Nevada’s was 13 percent. Among southern states, Georgia and Virginia had the lowest percentages of preterm birth: 12.6 and 11.8 percent, respectively.

The trends within the four major geographic regions show that the proportion of preterm births in the Northeast increased throughout the 1990s, with a small decline from 1999 to 2000 (MOD, 2005a,b,c,d). From 1996 to 2002, the proportion remained below the national percentage (12.1 percent). The percentage of preterm births in the Midwest during this time period was roughly equivalent to the national percentage. Western states had the lowest proportion of preterm births from 1996 to 2002 compared with the percentages in other parts of the country. Southern states had the highest percentage of preterm births in the United States from 1996 to 2002. This percentage steadily increased and remained above the national average during this period. (See Appendix B for further discussion of the geographic and sociodemographic variations in the rates of preterm births.)

International Comparisons

It is widely reported that the rates of preterm birth in the United States are anomalously high compared with those in other developed countries. However, there is a paucity of published international reports providing unbiased comparisons of the rates of preterm birth among countries. Many of the data that are available have compared countries by the rates of low birth weight. For example, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO) (UNICEF and WHO, 2004) reported estimates of the incidence of low birth weight. Nevertheless, such reports emphasize that international comparisons and trends must be interpreted cautiously and typically do not allow conjectures on the range of determinants that may underlie the observed differences in the rates of preterm birth to be made. Table 1-1 displays the incidence of low birth weight in selected developed and developing countries.

TABLE 1-1 UNICEF and WHO Estimates of the Incidence of Low Birth Weight

Several cautions are noted in comparing these data across countries (UNICEF and WHO, 2004). First data from industrialized countries are obtained mostly from service-based data and national birth registration systems, while data from developing countries are derived from national household surveys and other routine reporting systems. In addition, the majority of infants in developing countries are not weighted at birth, although an attempt is made to adequately adjust the data. Among developed countries, there are differences in definitions used reporting births (for example, cutoffs for registering births and birth weight). These data are also not corrected for variables such as maternal age, race, social and economic disadvantage, and health care factors.

A report by the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System cited a rate of 7.1 preterm births per 100 live births in 1996; in comparison, the rate in Australia was 6.9 and that in the United States was 11.0 (McLaughlin et al., 1999). Reporting of data on preterm birth rates at the international level is problematic, however, because substantial differences in the definitions of live births and fetal deaths exist in different countries, which affects the rates of preterm birth. These differences stem from variations in vital record reporting, laws, and procedures. Among the different countries, the impact of different standards of practice related to the measurement of gestational age is often unclear (see Chapter 2 for discussion of measurement issues). It may not be known what measure is typically used to estimate gestational age; for example, ultrasound or the first day of the mother’s last menstrual period. Some nations rely on periodic surveys rather than vital records to establish preterm birth rate trends. In addition to measurement issues, there are variations in demographic and health variables, as described above. Therefore, observations of marked differences in preterm rates between European countries and the United States are fraught with the potential for error. Currently, the twofold and greater differences in very preterm rates among U.S. states are largely unexplained. Establishing which factors underlie similar or greater variations among countries is an even larger task.

Method of Delivery

There has been a shift toward earlier delivery for infants of all gestational ages, which may reflect the increase in use of practices such as induction of labor and cesarean delivery (CDC, 2005i; MacDorman et al., 2005). In 2003, the rate of cesarean delivery was 27.5 percent of all births. The rate was 20.7 percent of all births in 1996 and 26.1 percent of all births in 2002. While the total rate of cesarean births increased for all gestational ages between 1996 and 2003, the highest increase was for preterm infants born at 32 to 36 weeks and those born full term (37 to 41 weeks gestation). In 2003, 49.5 percent of infants born at less than 32 weeks gestation and

37.3 percent of infants born at 32 to 36 weeks gestation were delivered by cesarean.

The rise in cesarean rates corresponds to a rise in maternal age. In 2003, the cesarean delivery rate for women 25 to 29 was 26.4 percent. For 35-39 year old women, the rate was 36.8 percent. This may be related to increased multiple births for older women, biological factors, or patient-practitioner concerns (Ecker et al., 2001; CDC, 2005i). Some findings suggest relatively low risks for maternal morbidity (for example, anesthesiarelated complications, infection) (Bloom et al., 2005; Lynch et al., 2003), while others suggest that there are increased risks such as readmission in the postpartum, infection, and complications related to anesthesia, among others (Koroukian, 2004; Hager et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005; Lumley, 2003).

Maternal Age

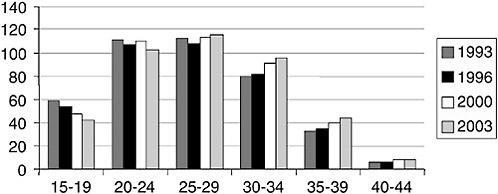

Dramatic demographic changes in the late 20th century have resulted in increased levels of education and rates of employment among women, including the employment of married women and mothers of young children. The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL, 2005) reported that in 2003 more than half of married American women and more than half of mothers of young children were employed, with the most highly educated women being the most likely to be working. The current proportion of women in the civilian workforce (56 percent) presents a 54 percent change from the proportion in 1980 (DOL, 2004). There has been an increasing trend for women to delay childbearing into their 30s. In 2003, women ages 30 to 34 experienced the highest birth rate for women in this age group since the mid-1970s and women ages 40 to 44 had the highest birth rate for women in this age group since the late 1960s (CDC, 2005a). For women ages 35 to 39, the birth rate increased 47 percent between 1990 and 2003, although the increase in the population of women aged 35 to 39 was only 7 percent (CDC, 2004a, 2005a) (Figure 1-5). A slight increase in the birth rate among women between the ages of 25 and 29 was observed in 2003. In contrast, over the past decade, the birth rates among adolescents (ages 15 to 19) and women ages 20 to 24 have decreased. The current birth rate among adolescents is the lowest rate recorded for this age group in the United States (CDC, 2005a).

Women age 35 and older have increased rates of preterm birth (see Figure 4-1 for discussion and also see Appendix B). Although adolescents also have increased rates of preterm delivery, the numbers of births among women in this age group, as noted above, have decreased in the last decade. Older mothers are more likely to have underlying medical conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension. The rates of these diagnoses reported in birth certificate data have risen since the early 1990s, in tandem with the rise in

FIGURE 1-5 Birth rates by age of mother, 1993 to 2003. The rates represent the number of live births per 1,000 women in each group.

SOURCE: CDC (2005a).

the mean maternal age (CDC, 2003c). These chronic health problems are associated with adverse birth outcomes, such as growth restriction, preeclampsia, and abruption, leading, in turn, to increases in the rates of indicated preterm deliveries.

ARTs, Multiple Births, and Preterm Birth

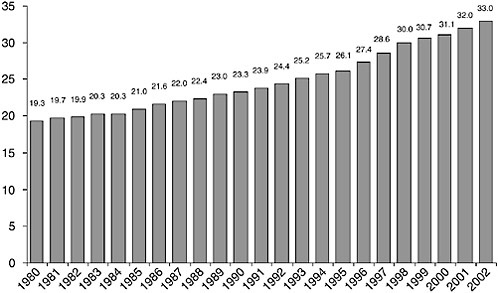

The incidence of multiple births has risen steadily in the past 20 years (Figure 1-6). Between 1980 and 2003 the rates of twin births climbed from 18.9 to 31.5 per 1,000 live births. The rates of triplets or higher-order multiple births increased from 37 to 187.4 per 100,000 live births. Multiple births are much more likely than singletons to be born preterm. The rise in multiple births is largely due to the use of ART (in vitro fertilization and other procedures in which the egg and the sperm are handled in the laboratory) (NCCDPHP, 2005), which is more frequently used by older women (see Chapter 5 for a discussion). In 2002, approximately 1 percent of infants born were conceived through the use of ART (NCCDPHP, 2005). Although the use of ARTs must be reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, this is not the case with other fertility treatments not classified as ARTs. These other treatments include those in which only sperm are handled (i.e., intrauterine insemination, which is also known as artificial insemination) or procedures in which a woman takes medication to stimulate egg production without the intention of having the eggs retrieved. The latter procedure is used to improve fertility, but the frequency of use of this technique and the number of births attributable to the use of this technique are not precisely known.

FIGURE 1-6 Multiple births as the number per 1,000 live births, 1980 to 2002.

SOURCE: CDC (2003c).

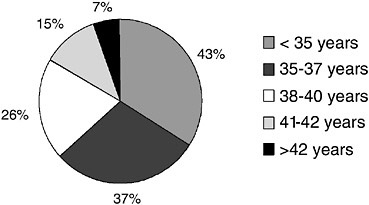

Women in their mid- to late 30s had the highest percentages of births conceived through the use of ART (Figure 1-7). Low birth weight infants are also a result of ART treatments, separate from their increased risk of preterm birth. Interestingly, singletons conceived through the use of ART have an increased risk of preterm birth than naturally conceived singletons. The incidence of multiple births is also related to the trend to delay child

FIGURE 1-7 Percentage of live births from ART by maternal age, 2002.

SOURCE: NCCDPHP (2005).

bearing. The reasons for this are unknown. Older mothers also are more likely than younger mothers to naturally conceive multiple fetuses.

Costs of Preterm Birth

In addition to the health problems associated with preterm birth described at the outset of this chapter, preterm birth is accompanied by broad emotional and financial costs and lost opportunities for families. The birth and hospitalization of preterm infants are associated with maternal distress (Eisengart et al., 2003; Singer et al., 2003) and maternal depressive symptoms (Davis et al., 2003). Longer-term outcomes are also apparent. Evidence suggests greater stress in families of school-age children who were born with very low birth weights; including perceptions of less parenting competence and more difficulty in parental attachment to the child (Taylor et al., 2001). The family as a unit is affected by the greater likelihood of not having additional children (Cronin et al., 1995; Saigal et al., 2000a), the financial burden (Cronin et al., 1995; Macey et al., 1987; McCormick et al., 1986; Rivers et al., 1987), limits on family social life (Cronin et al., 1995; McCormick et al., 1986), high levels of adverse family outcomes (family stress and dysfunction) (Beckman and Pokorni, 1988; Singer et al., 1999; Taylor et al., 2001), and parents’ difficulty maintaining employment (Macey et al., 1987; Saigal et al., 2000a). The impact of caring for a child born preterm may also contribute to the strength of the family. There is evidence that parents may perceive positive interactions with friends and within the family stemming from their efforts to care for their child born with birth weight less than 1,000 grams. These parents also reported enhanced personal feelings and improved marital closeness (Saigal et al., 2000a).

On the basis of estimates prepared by the committee (see Chapter 12), the annual societal economic burden associated with preterm birth in the United States was in excess of $26.2 billion in 2005, or $51,600 per infant born preterm. The share that medical care services contributed to the total cost was $16.9 billion ($33,200 per preterm infant), or about two-thirds of the total cost, with more than 85 percent of that medical care delivered during infancy. Maternal delivery costs contributed another $1.9 billion ($3,800 per preterm infant). Special education services associated with a higher prevalence of four disabling conditions (cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hearing loss, and visual impairment) among preterm infants added $1.1 billion ($2,200 per preterm infant), whereas lost household and labor market productivity associated with such disabling conditions contributed $5.7 billion ($11,200 per preterm infant).

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Preterm Birth

The large disparities in the proportion of preterm births and other birth outcomes between racial and ethnic groups in the United States have been persistent and troubling. The categorization of racial and ethnic groups is difficult and controversial because there is no simple method for defining these groups or subgroups. However, it is important to collect data on race and ethnicity to document and assess health status and health outcomes for various groups of the U.S. population. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget provides a classification system of race and ethnicity to study the social, demographic, health, and economic characteristics of various groups in the United States (EOP, 1995). That system comprises five racial group categories (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and white) and two categories for ethnic groups (Hispanic or Latino and not Hispanic or Latino) (EOP, 1995). Newborn infants and fetal deaths are categorized on the basis of the self-reported race of the mother (CDC, 2005d). The data presented in this section were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics, and the discussion in this section uses this classification system.

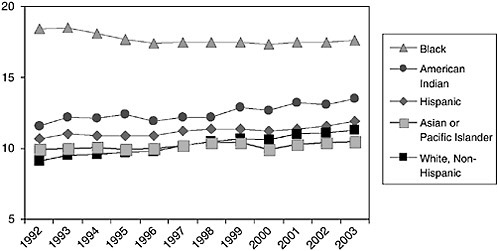

Explaining and trying to remedy the significant racial disparities in the proportion of preterm births should be a priority for the research and the health care communities. The most striking disparities are between non-Hispanic white and black women and between Asian or Pacific Islander women and black women (Figure 1-8). Although the highest percentages of

FIGURE 1-8 Preterm births as a percent of live births, by race and ethnicity, 1992 to 2003.

SOURCE: CDC (2004a).

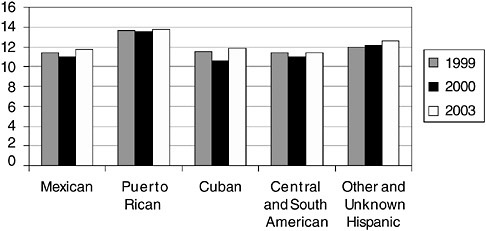

FIGURE 1-9 Preterm births as a percent of live births, by Hispanic subgroups, 1999, 2000, and 2003.

SOURCES: CDC (2001, 2002a).

preterm births occur among non-Hispanic blacks and the lowest percentages occur among Asians and Pacific Islanders, the most notable increases in the percentages of preterm births from 2001 to 2003 were for the white non-Hispanic, American Indian, and Hispanic groups. Overall, the rise in the proportion of preterm births in the United States was due mostly to the increase among the non-Hispanic white population.

The proportion of preterm births among white non-Hispanic women increased from 8.5 percent in 1990 to 11.3 percent in 2003. The proportion has remained fairly stable among Asian and Pacific Islander women (at about 10 percent). Among black women, although the proportion decreased from 18.9 percent in 1990 to 17.8 percent in 2003, overall, these women continue to experience much higher proportions of preterm births.

Although the proportion of preterm births among Hispanic and Asian-Pacific Islander women are the lowest of those among the ethnic and racial minority groups, these are not homogeneous populations. Considerable variation in preterm birth percentages exists among subpopulations of these populations. Although the percentage of preterm births for Hispanics in the United States was 11.9 in 2003, the percentages within subgroups of the Hispanic population ranged from 11.4 to 13.8 percent (Figure 1-9). Compared with other Hispanic subgroups, Puerto Rican women had the highest percentages and Central and South American women had the lowest.

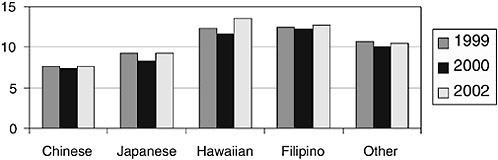

In 2002, the Asian and Pacific Islander subgroups of American women had preterm birth percentages that ranged from 8.3 to 12.2 (Figure 1-10). The Hawaiian (11.7 percent) and Filipino (12.2 percent) subgroups of

FIGURE 1-10 Preterm births as a percent of live births by Asian and Pacific Islander subgroups, United States, 1999, 2000, and 2002.

SOURCES: CDC (2001, 2002a).

American women had the highest percentages, which were also above the overall percentage among Asians and Pacific Islanders (10.6 percent). Women of Chinese descent had the lowest percentages from 1999 to 2002.

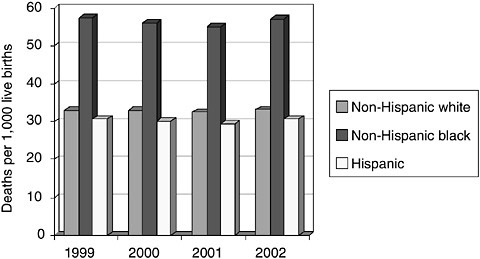

Significant disparities in the mortality rates among infants born preterm also exist (Figure 1-11) (see also Appendix B for an additional discussion of the gestational age-specific IMRs among black and white infants). The mortality rates are significantly higher for non-Hispanic black infants than for

FIGURE 1-11 Mortality rates for preterm infants (less than 37 weeks of gestation) by race or ethnicity, 2002.

SOURCE: CDC (2005c).

non-Hispanic white and Hispanic infants. In 2002, there were 57.3 deaths per 1,000 live births for black infants born at less than 37 weeks of gestation. In contrast, the mortality rates were 33.2 deaths per 1,000 live births for white infants and 30.7 deaths per 1,000 live births for Hispanic infants.

Many believe that differences in family socioeconomic conditions explain the differences in the risk for preterm birth by race, particularly between African American and white, non-Hispanic women. However, evidence suggests that the differences in the rates of preterm birth between African American women and white women, as well as the differences in the birth weights and the rates of infant mortality, remain after attempting to adjustment for the family’s socioeconomic condition (Collins and Hawkes, 1997; McGrady et al., 1992; Schoendorf et al., 1992; Shiono et al., 1997). Investigators have noted that even after attempting to adjust for socioeconomic condition, substantial differences in income and other related variables remain (Schoendorf et al., 1992). (see Chapter 4 for a full discussion of the sociodemographic factors associated with preterm birth).

CONTENT AND STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT

The purpose of this report is to assess the state of the science on the causes of preterm birth, address the health and economic costs of preterm birth for children born before term and their families, and establish a framework for action in addressing the range of priority issues, including a research and policy agenda for the future. The report is divided into five sections (Table 1-2). Section I reviews and discusses the definitions and terms used to describe the population of preterm infants (Chapter 2). Section II reviews the major categories of research investigating the causes of preterm birth: behavioral and psychosocial factors, sociodemographic and community factors, medical and pregnancy conditions, biological pathways, gene-environment interactions, and environmental toxicants (Chapters 3 to 8). Section III assesses the current understanding of the diagnosis and treat-

TABLE 1-2 Report Organization

|

Section |

Chapter(s) |

|

|

I. |

Measurement |

2 |

|

II. |

Causes |

3 to 8 |

|

III. |

Diagnosis and Treatment |

9 |

|

IV. |

Consequences |

10 to 12 |

|

V. |

Research and Policy |

13 to 15 |

ment of spontaneous preterm labor (Chapter 9). Section IV explores the consequences of preterm birth including health, developmental, social, psychological, educational, and economic outcomes (Chapters 10 to 12). The final section explores research and policy considerations and concludes with the committee’s proposed research agenda for the investigation of preterm birth (Chapters 13 to 15). Recommendations are provided at the end of each section. Table 1-3 describes the points of the committee’s charge and the corresponding chapters in which they are addressed.

TABLE 1-3 Committee Charge Points and Report Location Where Addressed

|

Committee Charge |

Chapter(s) |

|

Review and assess the various factors contributing to the growing incidence of premature birth |

3 to 8 |

|

Assess the economic costs and other societal burdens associated with premature births |

10, 12 |

|

Address research gaps/needs and priorities for defining the mechanisms by which biological and environmental factors influence premature birth |

15 |

|

Explore possible changes in public health policy and other policies that may benefit from more research |

14 |

|

Identify major obstacles to conducting clinical research, which may include

|

13 |

|

Provide strategies for removing barriers, including those targeting resident career choices, departments of obstetrics and gynecology, agencies and organizations that fund research, and professional organizations |

13 |