5

Global Disease Surveillance and Response

OVERVIEW

In the previous chapter, Fidler characterized surveillance as the “‘center of gravity’ for public health governance” and, along with Tomori, asserted that efforts toward global governance are unlikely to succeed unless the benefits afforded by surveillance are equitably distributed. The essays collected in this chapter highlight strategies to address this challenge, and that of enlisting global, multisectoral support for infectious disease surveillance and response efforts both within and beyond the purview of the International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005.

The first paper, by speaker David Bell of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), was originally published in the Far Eastern Economic Review in October 2008. Bell argues that, given the disruption of trade and tourism attributed to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the likely far greater consequences of pandemic influenza, “business, trade, and tourism stakeholders, and those who support them, such as the insurance industry, have a strong vested interest in working with public health authorities to promote global health security.” However, he observes, many representatives of trade and tourism are unfamiliar with the concept of global health security and the IHR 2005, and they may not realize how their participation in efforts to advance a global health agenda can serve their specific business interests.

Bell suggests that the private sector could be effectively (and profitably) engaged in addressing the challenge of public health capacity-building through investment, “in kind” assistance, or partnership with governmental and nongovernmental public health agencies. He also proposes that an international scheme to compensate individuals or countries for economic hardships resulting

from infectious disease outbreaks could be created as a public-private partnership involving trade and tourism stakeholders, and structured as a trust fund or insurance product. “In summary,” Bell writes, “the public-health sector needs help in implementing the IHR; recognition of their importance to trade security can provide the basis for engagement of trade and tourism stakeholders.”

Several important collaborations among nongovernmental organizations support infectious disease surveillance and response efforts and the larger goal of global health security. In his contribution to this chapter, Ottorino Cosivi of the World Health Organization (WHO) discusses that organization’s partnerships with a broad range of organizations; the most significant of these are the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), which, together with the WHO, are referred to as “the three sisters.” He describes a variety of interagency collaborations to promote the early detection and control of disease at the animal-human interface, including the aforementioned Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), the Global Early Warning and Response System for Major Animal Diseases, Including Zoonoses (GLEWS), the International Food Safety Authorities Network (INFOSAN), and the Mediterranean Zoonoses Control Program.

“In order to address the threat of emerging zoonotic diseases, we must change the paradigm for disease prevention and focus on disease surveillance and control in animals,” Cosivi observes. This is the reasoning behind the One World, One Health strategic framework, which aims to prevent and to prepare for a range of potential global health risks through collaboration at the intersection of animal and human health. Cosivi discusses the development of this framework, which evolved from lessons learned in efforts to address the threat of pandemic avian influenza and its current activities. Partners in the One World, One Health® framework currently include the WHO, FAO, OIE, the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the World Bank.

A representative of another of the “three sisters,” workshop speaker Alejandro Thiermann of the OIE discusses global surveillance and health security from the perspective of animal health in this chapter’s third essay. Focusing on the obligation of OIE member nations to report cases of known zoonotic disease threats, as well as of any “emerging disease with significant morbidity or mortality, or zoonotic potential,” Thiermann compares and contrasts the OIE’s disease surveillance program with its human-health counterpart, the IHR 2005. He describes the OIE’s notification requirements, how such information is conveyed to members, and how the organization collaborates with the WHO and the FAO to obtain and respond to outbreak information from unofficial sources through networks such as GOARN and GLEWS.

The OIE engages in a range of activities to build global surveillance capacity, including funding and technical assistance for countries with inadequate ability to detect and report disease threats, according to Thiermann. He also notes that, in recognition of the important role of compensation in ensuring timely and accurate

reporting of disease threats, the OIE offers guidance for establishing compensation systems. The OIE has also founded a “virtual vaccine bank,” which has supplied large quantities of vaccines to address severe outbreaks of avian influenza (in birds). “This mechanism allows countries to begin vaccinating with certified vaccines, immediately after the decision is made that vaccination is needed to control the serious outbreak, and without having to wait for the administrative process of securing the funds and identifying the supplier of vaccines,” Thiermann states.

In the final essay of this chapter, workshop speaker David Nabarro of the UN reflects on his experience as that organization’s coordinator for avian and human influenza and for global food security. While attempting to respond to the increasingly worrisome prospect of an avian influenza pandemic in humans, Nabarro and colleagues collaborated with stakeholders from the public, private, and volunteer sectors and found that most recognized the value of working together on disease surveillance, reporting, and response. “They found it both operationally useful and reassuring in a situation where there was considerable political urgency and need for concerted action by institutions,” he writes. “They have joined together to support the evolution of an inclusive movement that enables hundreds of different stakeholders to feel at home.”

From these observations, Nabarro distilled several “factors for success” and additional “incentives for success” for global health collaboration. He then explores major challenges to establishing surveillance as a foundation for global public health governance (as embodied in global efforts toward influenza pandemic preparedness, and more generally in the IHR 2005, OIE regulations, and One World, One Health® framework). In addition to the previously discussed needs for surveillance capacity-building and stakeholder engagement, Nabarro adds a third, more general necessity: creating trust, which he deems the most important incentive for participation, and one which requires active maintenance. “We need to insure against periods of mistrust that may build up in relationships that are otherwise very good,” he writes. “We have to know that we are able to cope with these periods.”

OF MILK, HEALTH AND TRADE SECURITY1

David M. Bell, M.D.2

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The melamine-contaminated milk that has sickened at least 53,000 infants is the latest public-health emergency to have triggered international concern and highlighted the need for improved global cooperation to prevent, detect and con-

trol health threats that may rapidly spread beyond national borders. Other recent examples include contamination of the drug heparin in 2007, the dumping of 500 tons of petrochemical waste in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire in 2006, and the SARS epidemic in 2003. Importantly, these health emergencies also disrupted business operations, trade and/or tourism.

The economic impact of the tainted milk is not yet known, although precautions are being taken by countries that import milk-containing products from China and rebuilding public confidence may take a long time. SARS caused a global economic loss estimated at $40 billion due to decreased trade and travel and the disruption of global supply chains. These disruptions would pale before that of a severe influenza pandemic, estimated by the World Bank to cost the global economy up to 4.8% of global GDP. According to the Unites States Congressional Research Service, trade disruptions during a pandemic could include countries banning goods from infected regions, travel bans due to protective health measures, or supply-side constraints caused by health crises in exporting countries. For these reasons, business, trade, and tourism stakeholders, and those who support them, such as the insurance industry, have a strong vested interest in working with public-health authorities to promote global health security.

An important new framework to promote global health security in the 21st century is the revised International Health Regulations (IHR), adopted by the 192 member states of the World Health Organization in 2005. Known as IHR 2005, it replaced the previous IHR 1969, which proved unable to address new health threats. The focus of the latest IHR shifted to prevention, detection, reporting and containment of “public health emergencies of international concern,” or PHEICs and discouraging trade and travel restrictions disproportionate to the threat. IHR 2005 became effective in 2007, with implementation required of member states by 2012.

The IHR also promote global trade security, which may be provisionally defined as maintenance of a stable trade environment by promotion of safe and unhindered travel and transport, stability of supply and distribution chains, continuity of business operations, and safety of imports and exports. Trade security has been mentioned in the context of protecting shipping lanes and more recently, intercepting terrorist cargo disguised as freight. In the 21st century, a broader concept is needed that also addresses disruption due to public-health emergencies. For businesses, industry associations and international trade organizations and their member states, promoting IHR implementation is good risk management, since the risk of business and trade disruption is reduced in countries where the IHR are implemented.

Overcoming Barriers

There are two major challenges to IHR implementation: technical and political/economic. Many countries, especially in the developing world, lack

the necessary infrastructure for prevention, detection, and control of disease outbreaks, toxic spills, unsafe food and drugs, or other PHEICs. Last year, to guide global capacity-building needs in the next five years, the WHO published “IHR 2005: Areas of work for implementation.” This ambitious document calls for global partnerships to “strengthen national disease prevention, surveillance, control and response systems; public-health security in travel and transport; WHO global alert and response systems; and the management of specific risks.” Building public health capacity is particularly important because it will enable countries to prevent and respond to public health emergencies regardless of whether they meet the IHR definition of a PHEIC. However, resources are insufficient and political will varies in light of competing priorities.

The nontechnical challenges are even more daunting. Countries may perceive substantial economic disincentives to reporting and responding to public health threats as required by the IHR. Economic harm to tourism or export industries could result from public health measures such as travel advisories, quarantine, seizure of hazardous products, or culling of infected livestock—or simply from unjustified public fears. Mounting an emergency response will challenge the health budget of many developing countries, yet the IHR includes no provision for financial support or compensation. Countries may be reluctant to request international assistance for various reasons, including national pride, desire to obtain primary recognition for research findings related to the event, or a commercial interest in biological samples obtained in surveillance or response activities.

On the bright side, national economic interests, such as protecting tourism, can promote government actions consistent with global health security. In late 2006, the Indonesian government suspended sharing influenza virus samples with WHO due to intellectual-property issues regarding vaccine development, thus compromising the global surveillance of influenza. Yet in August 2007 samples were sent from a patient who died of avian influenza in Bali. According to the Indonesian Health Ministry, the specimens were sent to the WHO Influenza Collaborating Center at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta “to prove that no mutation took place in the virus and to inform people in the world that Bali was still a safe place to visit.” Although Indonesia did not resume sending specimens from elsewhere in the country, this incident illustrates that enlightened economic self-interest can be leveraged to promote health security.

The IHR are intended to avoid unjustified governmental restrictions on international trade and travel in a PHEIC, but have no enforcement mechanism and do not apply to private entities which may implement such restrictions on their own. IHR implementation is primarily the responsibility of health ministries, yet the trade and tourism sectors have much to lose in a disease outbreak and often have more influence on government policy than do health ministries. In summary, the public-health sector needs help in implementing the IHR; recognition of their importance to trade security can provide the basis for engagement of trade and tourism stakeholders.

A Path Forward

Many trade and tourism stakeholders may not realize they have a vested interest in IHR implementation. Many are unfamiliar with the IHR and its recent shift in focus. Others recognize the potential adverse economic impact of a health emergency, but consider early detection and control to be the responsibility of public-health authorities. Since many companies appear to believe that these events are like unpredictable and unpreventable hurricanes, their risk management strategy, if any, is limited to minimizing damage if the storm hits them. These companies may not realize the benefits of early detection and containment to their own risk-management strategy, or the daunting challenges faced by public-health authorities in implementing early measures. That is, stakeholders may have an implicit understanding of the importance of health security for trade security, but not as a goal they should pursue.

On a technical level, many companies and industries can potentially assist countries to meet the new IHR infrastructure requirements. Industries in the aviation and maritime sectors have long collaborated with public-health authorities regarding measures at points of entry, but many other trade and tourism stakeholders have an interest in promoting safe and expeditious travel and transport through these critical sites as well. Since PHEICs are most effectively detected and contained in communities rather than at borders, IHR 2005 requires, for the first time, that countries develop public-health infrastructure throughout their territories. This difficult challenge may offer an opportunity for direct private-sector engagement.

Larger companies or their nonprofit foundations could invest by providing resources to individual countries or the WHO to help countries through its IHR Implementation Plan. Investments might include funding and “in kind” assistance, e.g., supplies, facilities, expertise, and transport capacity. Small- and medium-sized firms also have a role, especially as partners in public health emergency response, e.g., in developing policies that encourage infectious employees to stay home and relaying health messages to workers and their families.

Countries are now developing their national action plans to meet IHR requirements by 2012, offering an opportunity for trade and tourism stakeholders to learn about these plans and consider investing in their success. Tabletop exercises with public-health officials and local case studies may help businesses understand their return on investment. Discussions have occurred at the World Economic Forum about roles for global business in disaster response that could help serve as a model.

Industry and political leaders should be encouraged to understand, before any event occurs, that it is always in their interest for public-health authorities to report and control a PHEIC rapidly, and to seek international assistance if appropriate. In the Internet age, news and rumors cannot be suppressed indefinitely. Temporary losses for a country’s tourism or export industries would be preferred over taking halfway measures leading to worsening conditions or a loss of trust

by the public and business partners at home and abroad. This message would be more influential coming from business communities and trade ministries than public-health officials.

Particularly challenging is the issue of compensation for businesses and their employees who suffer economic losses when a country complies with the IHR and WHO advice in controlling a PHEIC. Even wealthy countries will have difficulty addressing this issue. It is unrealistic to expect developing countries to bear the economic consequences of disease-control measures unassisted. The experience gained in compensating poultry farmers for culling to contain avian influenza outbreaks illustrates that such programs can be helpful when appropriately designed and implemented and that international financial and technical assistance may be required.

The availability of partial compensation to countries through an internationally supported mechanism should be established before any PHEIC, as well as procedures and criteria for disbursing aid. Ad hoc donations afterwards will be too late to influence decision making or cushion the immediate losses of businesses and workers who have little financial reserves. To promote IHR implementation, public-health and business leaders might consider establishing an international trust fund or insurance product. This could be done as a public-private partnership involving an agency such as the World Bank or WEF.

Trust funds are typically supported by a tax on specific transactions, which may be unpopular, whereas the concept truly is insurance, perhaps purchased by countries and industry consortia. Insurance premiums for many developing countries would need to be subsidized, but donors might consider this as a worthwhile investment. Insurance companies have experience in writing policies to cover many unusual eventualities and it is not inconceivable that a sound product could be designed. Many large companies already have business-interruption insurance for known risks. While commercial insurance is likely beyond the reach of many small businesses in developing countries, this approach could serve as a model for a policy to cover entire communities or perhaps critical industries and their suppliers. Conditioning the insurance on improvements in public-health and emergency management infrastructure could help justify these improvements as attractive investments, rather than costs. Many details would need to be worked out, including what losses would be covered, how claims would be adjudicated, and to whom claims would be paid. The national government might be a likely candidate, to the extent that it incurred verifiable expenses in disease control and in compensating private companies or citizens.

An initiative by major trading nations and business sector champions is needed to engage trade and tourism stakeholders to promote implementation of the revised IHR. Focusing on trade security would help avoid entanglement in more controversial health-trade issues like drug pricing. Activities may include raising awareness in business sectors and organizations like the WTO, seeking resources to help the WHO and member states strengthen core public health

capacity, developing novel compensation mechanisms to offset economic disincentives to IHR adherence, drafting codes of good practice, and promoting evaluation of public-health interventions.

Global trade security depends on global health security, including IHR implementation. Public-health, trade and tourism stakeholders have much to gain from joining forces to promote both and much to lose from failing to recognize their common interests.

INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL AGENCIES WORKING AT THE HUMAN-ANIMAL INTERFACE

Ottorino Cosivi, D.V.M.3

World Health Organization

Following World Health Day in 2007 (WHO, 2007a), the World Health Report (WHO, 2007b) defined the concept of global health security and identified major threats to global health security. Emerging infectious diseases, particularly foodborne diseases and zoonoses,4 figure prominently among these risks, which also include international crises and humanitarian emergencies; deliberate use of biological, chemical, and radioactive agents to cause harm; and environmental disasters. International actions to address international crises; deliberate use of biological, chemical, and radioactive agents; and environmental disasters require primarily political partnerships. Conversely, technical and scientific partnerships are required to effectively address emerging infectious diseases. Many such partnerships focus on the prevention of foodborne and zoonotic diseases as an important means to protect public health, as well as to promote the production of food of animal origin and facilitate international trade in animals and animal products.

The main message of the 2007 World Health Report (WHO, 2007b) is that collective action is needed to address global health risks. Such collective action is embodied in the tripartite relationship of the WHO, the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE),5 and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Together, these agencies are confronting emerging zoonoses such as Rift Valley fever, which has had both dire public health and economic effects on vulnerable populations in Africa; and influenza, with efforts to address the emergence of the new influenza A (H1N1)—building on preparations under way since the emergence of H5N1 avian influenza.

The International Health Regulations (IHR) provide a framework for managing collective risks (WHO, 2009a). They emphasize that the best way to limit the public health impact of emerging diseases is by strengthening national preparedness and response activities in order to enable the early detection of health threats and the efficient implementation of response actions, thereby addressing problems at a manageable stage. At the international level, WHO’s alert and response operations under IHR (see Heymann in Chapter 4) are linked to similar systems for animal health managed by the OIE and FAO.

FAO, OIE, and WHO

WHO pursues collaborations to address emerging infectious diseases with many different organizations and partners, and at multiple levels, but for those infectious agents originating from animals and animal products its primary relationships are with the OIE and FAO. The ambitious, overarching definition employed by the WHO—that “health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”—subsumes the goals of the FAO (food security and poverty alleviation) and the OIE (transparency in reporting information on animal diseases and the development of international standards for animal health and welfare). There are major structural and organizational differences among these agencies in terms of number of staff, governance, and budget. Each of the organizations brings to the table a different valuable perspective on the fight against zoonotic disease. Table 5-1 lists several important formal agreements and joint programs undertaken by the FAO, OIE, and WHO to address zoonoses.

Several different interagency frameworks for the early detection and control of zoonotic diseases build on synergies among these organizations. Some of these activities, such as the GLEWS (WHO, 2006) and INFOSAN (WHO, 2007c), support global public health surveillance, which is discussed in greater detail later. Other programs include the WHO’s Global Salm-Surv and the Mediterranean Zoonoses Control Programme (MZCP), which focus on strengthening capacity for disease detection and control at the national level. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)/WHO Regional Office for the Americas has long been providing technical cooperation to member states in veterinary public health. Its operations have been consolidated and decentralized to the Pan American Center for Foot-and-Mouth Disease (PANAFTOSA6) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

|

6 |

Founded in 1951, PANAFTOSA is one of the specialized centers of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Located in the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro, the center supports the member states of the region in the prevention, control, and eradication of zoonotic and food-borne diseases and high consequence animal diseases, primarily foot-and-mouth disease (FMD). For more information, see http://www.panaftosa.org.br/ (accessed October 23, 2009). |

TABLE 5-1 Formal Agreements and Joint Programs to Address Zoonotic Diseases

|

Parties |

Date |

Purpose of Agreement or Joint Program |

|

WHO, FAO(a) |

1948 |

Joint committees, joint missions, exchange of information, inter-secretariat committees |

|

WHO, OIE(a) |

1960 (revised 2004) |

Promotion and improvement of veterinary public health, and food security and safety |

|

PAHO, OIE(b) |

2000 |

Technical cooperation in the field of veterinary public health |

|

FAO, OIE(c) |

2004 |

Role of FAO, role of OIE, and joint actions |

|

FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission(d) |

1963 |

Develop food standards, guidelines and related texts such as codes of practice |

|

SOURCES: WHO (2007a), OIE (2000b; 2004c), Codex Alimentarius (2009). |

||

There is also collaboration between WHO, OIE, and FAO to address specific health threats such as influenza, antimicrobial resistance, and laboratory bio-safety challenges. With regard to avian and pandemic flu, these include WHO’s interactions with the OIE/FAO animal influenza laboratory network (OFFLU), which shares information on viral strains with WHO (FAO and OIE, 2009). Efforts spearheaded by the WHO to address other health threats at the animal-human interface—from rabies to biological agents that have been associated with deliberate use to cause harm like anthrax, brucellosis, and tularemia—also draw on the additional expertise, laboratory services, and surveillance data from OIE and FAO.

WHO, FAO, and OIE hold strategic level tripartite meetings regularly. Moreover, exchange of information and technical expertise among these agencies occurs on a daily basis and has intensified considerably over the past decade.

Collaborative Approaches Addressing Zoonoses, Food Safety, and Veterinary Public Health

GLEWS

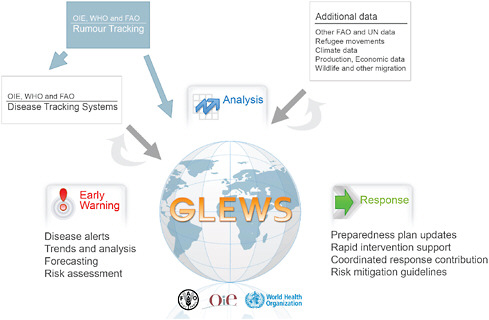

A formalized initiative of the WHO, FAO, and OIE, GLEWS is a public and animal health early warning system intended to reduce incidence of emerging infectious diseases. Partners in GLEWS, which incorporates both agriculture and public health sectors, share information on disease outbreaks in real time and coordinate their responses, as shown in Figure 5-1. GLEWS combines and coordinates the alert and response mechanisms of the OIE, FAO, and WHO to assist in prediction, prevention, and control of emerging infectious diseases.

This international platform is among the most effective means by which these agencies currently collaborate, as was recently demonstrated when the

FIGURE 5-1 Global Early Warning and Response System (GLEWS) for Major Animal Diseases, including Zoonoses.

SOURCE: OIE (2009).

Ebola Reston virus was identified in pigs and humans in the Philippines. Information was gathered and shared by the three organizations through GLEWS, which also facilitated the coordination in the communication to the public. In addition, GLEWS provides information to aid in predicting outbreaks of emerging diseases such as Rift Valley fever.

INFOSAN

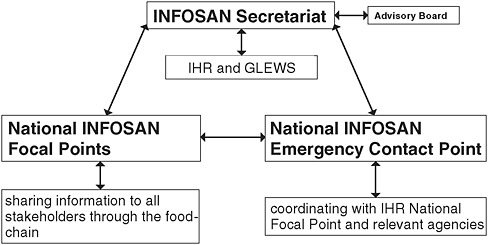

The INFOSAN network promotes global food safety by disseminating information and fostering international collaboration. As of May 2009, 177 countries have designated more than 350 INFOSAN Emergency Contacts and INFOSAN Contact Points. As shown in Figure 5-2, INFOSAN links to all stakeholders along the “food chain”—including the private sector—and coordinates with IHR and GLEWS. This also means that emergency information related to foodborne diseases and contamination in some cases do not only reach countries through this FAO/WHO mechanism focusing of food safety authorities

FIGURE 5-2 INFOSAN links to all government sectors involved in food safety.

SOURCE: Reprinted from WHO (2007c) with permission from the World Health Organization.

Global Foodborne Infections Network (GFN)

Recognizing that food safety requires intersectoral collaboration among human health, veterinary, and food-related disciplines, the WHO developed the Global Foodborne Infections Network (GFN) (formerly known as Global Salm-Surv, GSS) in order to enhance countries’ capacity to detect, respond, and prevent foodborne diseases (WHO, 2009c). The GFN promotes integrated, laboratory, and epidemiologically based foodborne disease surveillance, which is expanding to incorporate zoonotic diseases. It supports international training courses, external quality assurance programs, research projects, reference services, and communication platforms, and provides national and regional interdisciplinary intersectoral networks and national training courses through train-the-trainer concept.

MZCP

Created in 1978 and financed by its 13 states, the MZCP (WHO, 2009b) fosters programs and activities for the prevention, surveillance, and control of zoonoses and foodborne diseases; strengthens collaboration between public health and animal health sectors; and promotes collaboration among countries. This program has achieved significant progress in bringing together the animal health and public health communities in countries in the Mediterranean region. Its training and capacity-building activities have included intersectoral surveillance of

zoonotic and foodborne diseases (e.g., rabies, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, and leishmaniasis), preparedness and response to zoonotic and foodborne disease emergencies (e.g., rabies, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, and leishmaniasis), and laboratory training. All of these activities are conducted jointly, on a regional basis, by public health practitioners and veterinarians.

PANAFTOSA

The countries of the Americas have long recognized that the health of animals and human beings are inextricably linked. In 1949, PAHO established a Veterinary Public Health (VPH) unit to bring together the animal and human health communities to address animal and zoonotic diseases of public health importance. Since 2007, PANAFTOSA has hosted PAHO’s VPH project. Its main areas of intervention include emerging and neglected zoonoses (e.g., dog rabies elimination), foot-and-mouth disease, food safety and foodborne diseases (Belotto et al., 2007). More recently the neglected diseases and tropical diseases research projects have been decentralized in PANAFTOSA. PANAFTOSA acts as the Secretary of the Inter-American Meeting, at the ministerial level, on Health and Agriculture (RIMSA), the Hemispheric Committee for the Eradication of Foot-and-Mouth Disease (COHEFA), the Regional Meeting of the National Directors of Rabies Control Programs in Latin America (REDIPRA), the South American Commission for the Control of Foot-and-Mouth Disease (COSALFA), and the Pan American Commission for Food Safety (COPAIA). These advisory bodies bring together regional and international stakeholders, including member states, academia, nongovernmental organizations, development agencies, and public and private entities including agriculture, health, and the food sectors.7

One World, One Health®

The concept of One World, One Health®, first defined by the Wildlife Conservation Society in 2004, has been further described by international organizations such as the FAO, the OIE, the WHO, the UN, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the World Bank (WB). This description was developed in response to a request made at the interministerial meeting of the December 2007 New Delhi International Ministerial Conference on Avian and Pandemic Influenza. This meeting suggested that the international community looks beyond avian flu to the next important global health risk related to the human-animal interface. In October 2008, a plan aiming at diminishing the threat and minimizing the global impact of epidemics and pandemics due to highly infectious and pathogenic emerging infectious diseases for humans and animals was presented at a follow-up International Ministerial Conference on Avian and Pandemic

|

7 |

For more information http://www.panaftosa.org.br/ (accessed May 29, 2009). |

Influenza, Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, October 2008. It builds on the lessons learned from the avian influenza crisis, which include:

-

The economic implications of infectious disease, which range from national development to individual livelihoods;

-

The role of wildlife in disease transmission;

-

The necessity for control strategies based on epidemiological evidence;

-

The importance of cross-sectoral and intersectoral collaboration in outbreak response;

-

The crucial role of political commitment to public health; and

-

The need for effective risk communication strategies.

The following six specific objectives and related activities have been determined in the document:

-

Develop international, regional, and national capacity in infectious disease surveillance, making use of international standards, tools, and monitoring processes.

-

Ensure adequate international, regional, and national capacity in public and animal health—including communication strategies—to prevent, detect, and respond to disease outbreaks.

-

Ensure functioning national emergency response capacity, as well as a global rapid response support capacity.

-

Promote interagency and cross-sectoral collaboration and partnerships.

-

Control animal influenza and other existing and potentially reemerging infectious diseases.

-

Conduct strategic research.

At the country level, an important long-term priority is the improvement of disease control capacity—including the public health, animal health, and food safety services—based on good governance compliant with IHR and OIE standards. At country and regional levels, over the short to mid term, a key goal is to establish risk-based zoonotic disease surveillance in humans and animals in order to recognize diseases at their point of origin (by identifying hotspots at the human-animal interface). The concept of global and national public goods was applied in this paper to describe further the potential future activities, as shown in Table 5-2.

Conclusions

In order to address the threat of emerging zoonotic diseases, we must make sure the paradigm for disease prevention and focus on disease surveillance and control at the human-animal interface reflects the fact that emerging infectious

TABLE 5-2 Activities for Prevention and Control of Diseases at the Animal-Human-Ecosystems Interface and Their Status as a Public Good

|

Activity |

Disease of Low Human Epidemic Potential |

Disease of Moderate to High Human Epidemic Potential |

|

1. Preparedness |

|

|

|

Risk analysis |

Global |

Global |

|

Preparedness plan |

National/regional |

Global |

|

Animal vaccine development |

Privatea |

Global |

|

2. Surveillance |

|

|

|

Public health, veterinary, and wildlife |

National |

Global |

|

Diagnostic capacity |

National/global |

Global |

|

Managerial and policy arrangements |

National/global |

Global |

|

3. Outbreak control |

|

|

|

Rapid response teams |

National |

National/global |

|

Vaccination |

National/regional |

National/global |

|

Cooperation among human, veterinary, and wildlife services |

National |

Global |

|

Compensation schemes |

National |

Global |

|

4. Eradication plans |

National/regional |

Global |

|

5. Research |

National/regional |

Global |

|

aThis may also be a global public good depending on diseases and circumstances (context). SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from FAO et al. (2008). |

||

diseases are dynamic risks and that their control is complex and requires a systems-based approach, with the active contribution of stakeholders from public to private sectors, and input from various disciplines such as public health, animal health and production, environment protection, conservation of wildlife. The main focus should always be the prevention of human disease but these efforts can be advanced through existing animal and human disease surveillance networks that need to be strengthened and enabled to communicate across sectors, and by defining research priorities addressing the needs of the most vulnerable regions of the world. National and regional capacity-building is key to infectious disease prevention and mitigation.

INTERNATIONAL ANIMAL HEALTH REGULATIONS AND THE WORLD ANIMAL HEALTH INFORMATION SYSTEM

Alejandro B. Thiermann, D.V.M., Ph.D.8

World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE)

The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE)9 is the international organization responsible for establishing international standards on animal health and zoonoses. The draft sanitary standards are presented to the 173 members for a vote and, once adopted, they are published in the Terrestrial and Aquatic Animal Health Codes10 as well as the accompanying manuals for diagnostics and vaccines.

When the OIE was established in 1924, its two primary objectives were to provide transparency of global animal health information and to provide scientific and technical support on the prevention and control of animal diseases. Today, the OIE’s mandates relate to improving animal health worldwide, which goes well beyond the notification obligations of the occurrence of animal diseases of significance. However, for the purpose of this paper, only the notification obligations by members are discussed.

The importance of credible and up-to-date animal disease information is critical to ensure transparency in the animal disease status worldwide. Therefore, the OIE has had the notification of the occurrence of significant animal diseases, including zoonoses, as one of its major objectives and a mandatory obligation for its members since its inception. The notification system has been reviewed and updated several times, and the most recent revision in 2004 was accompanied by the launching of the current World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS) platform.

Already in 1924, when the agreement on the creation of the OIE was signed, the organic rules prescribed clearly that the OIE members have an obligation to inform the OIE of changes in the epidemiology of major diseases listed by the OIE (OIE, 2006).

Under Article 4b, “the statues identify that the main objective of the OIE is to collect and bring to the attention of the governments or their sanitary services all facts and documents of general interest concerning the spread of epizootic diseases and the means used to control them” (OIE, 2006).

Under Article 5, the statues state that the governments shall forward to the OIE, by telegram, notification of the first cases of rinderpest or FMD observed in a

country or an area hitherto free from the infection. They must also forward, at regular intervals, bulletins prepared according to a model adopted by the International Committee (the highest authority of the OIE, comprising all member countries), giving information on the presence and distribution of the following diseases: rinderpest, rabies, FMD, glanders, contagious pleuropneumonia, dourine, anthrax, swine fever, and sheep pox.

Article 5 also states that the list of diseases to which either of the foregoing provisions applies may be revised by the International Committee, subject to the approval of the governments.

The governments shall also inform the OIE of the measures adopted by them to control epizootics, especially such measures enforced at their own frontiers to protect their territory against import from infected countries. As far as possible they shall furnish information in reply to inquiries sent to them by the OIE. (OIE, 2006)

This agreement is still today an obligation for members.

Under Article 9, the statues state that all information collected by the OIE shall be brought to the attention of the participating states by means of a bulletin or by special notifications which shall be sent to them either automatically or upon request. Notification concerning the first outbreaks of rinderpest or FMD shall be forwarded immediately by telegram to the various governments and sanitary services. In addition, official reports shall be sent periodically to the participating states, giving detailed accounts of the activities of the OIE. (OIE, 2006)

The scope of Article 5 was later enlarged by covering a broader list of animal diseases, including zoonoses, and by addressing emerging diseases (even if they are not OIE-listed diseases). These changes are reflected in the Terrestrial Animal Health Code Chapter on notification, as early as 1986. The Code states that veterinary administrations shall send to the OIE notification, within 24 hours, of any new findings, even of diseases not listed under list A, which are of exceptional epidemiological significance to other countries. In May 2004, OIE members approved the creation of a single list of diseases (see Table 5-3), thereby eliminating the organization of diseases under lists A, B, and C.

Further improvements to the chapter on notification and the criteria for listing diseases were also adopted in 2004, where specific reference was made to the obligation to notify of “an emerging disease with significant morbidity or mortality, or zoonotic potential.”

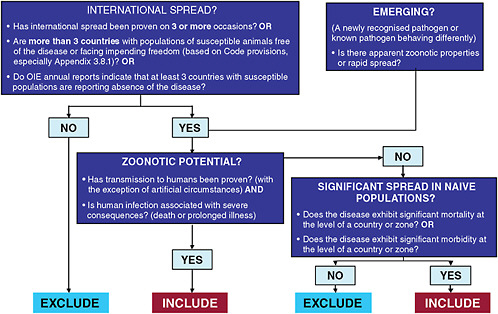

Currently, the Terrestrial Animal Health Code describes the notification obligations for members and provides a list of the notifiable diseases. The OIE’s notification criteria are based on a decision tree (Figure 5-3) that incorporates several factors such as the ability of the pathogen for international spread, as well as

TABLE 5-3 Diseases Notifiable to the OIE

|

Multiple species diseases

|

Cattle diseases

|

|

Swine diseases

|

Sheep and goat diseases

|

|

Bee diseases

|

Equine diseases

|

|

Mollusk diseases

|

Avian diseases

|

|

Amphibians

|

Lagomorph diseases

|

|

Fish diseases

|

Crustacean diseases

|

|

Other diseases

|

|

|

SOURCE: OIE (2009a). |

|

the ability to spread within a naïve animal population and its zoonotic potential. This decision tree is not limited to known pathogens; it also takes into account the emergence of new diseases that are potentially zoonotic and/or show an effect on naïve animal populations, and which may still not have a characterized etiologic agent. This has been recently demonstrated by the emergency notification made by Canada when it detected influenza A (H1N1) in a pig herd in Alberta. Swine influenza is a mild disease of swine and therefore not a notifiable disease by the OIE. The recent epidemiologic event of the first reported evidence of an infection in pigs with this novel strain constituted a case for emergency notification. Canada, demonstrating an efficient surveillance system and transparent reporting, immediately notified the OIE and thereby the international community became aware. Should the human infection with this pathogen be associated with severe consequences, then it would trigger the mechanism for consideration for “notifiable disease.”

The new notification system also takes into account the concept of infection without necessarily having expression of clinical disease. It takes into account any change in epidemiological situations, whether it is manifested as a difference in pathogenicity or a change in host predilection, regarding known diseases within a country or zone. It also clarifies how to deal with the appearance of emerging diseases.

The events that require immediate notification (within 24 hours) are those related to the emergence of a new disease, as well as the first occurrence of a listed disease or infection in a country or zone. This also applies to the reoccurrence of a listed disease or infection in a country or zone having been previously

declared free of such disease. It also applies to the first occurrence of a new strain of a pathogen of a listed disease, or of a previously unknown condition manifesting a significant impact on animal or public health in a country or zone.

The information received by the OIE is processed, presented in several formats, and then published on the OIE website. The immediate notifications of diseases, infections, or unusual epidemiologic events are published upon receipt, on a near-real-time basis. This is followed by weekly reports, which contain weekly updates submitted by countries on the initial notifications, until the outbreak is eliminated or the situation is such that the country or zone is declared endemic.

The OIE also publishes semiannual reports, which contain qualitative as well as quantitative information. The qualitative information describes the occurrence of the disease and the control, prophylaxis, and prevention measures being applied. The quantitative information is presented in different formats: the presence of the disease or infection within the lowest administrative division within the country (province, county, or department) monthly, and every six months; it is also presented by entire countries by month and for the six-month period. Finally, there is an annual report that summarizes country submissions not only on the listed diseases, but also provides relevant information on non-OIE-listed diseases; information on the veterinary infrastructure of the country; reports from the various reference laboratories; any relevant information to animal census conducted; the summary of human cases of zoonotic diseases; as well as any information on the production of vaccines.

Members meet their notification obligations by directly entering the related information electronically into the WAHIS web application, using a protected login and password. Only a minority of members continue to enter their information in paper form and submit it to the OIE via fax. To facilitate contact with those individuals responsible for collecting and submitting information to the OIE, each delegate (in most cases the chief veterinary officer of a given country) must identify and notify the OIE of their selected disease notification focal point.

This new notification system provides members with a simpler and more rapid method for complying with the obligation of sanitary information submissions. It also permits countries to benefit from new capabilities for accessing and retrieving valuable epidemiological information in various ready-to-use formats. The various forms of data presentation can be examined when accessing the World Animal Health Information Database (WAHID).11 The information can be retrieved in various forms: by country, by disease, based on control measures applied, and by comparing the disease situation between two countries. There are also graphic presentations of maps depicting exceptional epidemiological events, specific disease distributions, as well as maps describing areas of control measures such as vaccinations. This information can be used to conduct risk

analysis, to prevent the spread of disease, as well as to minimize the transmission of diseases as a result of international trade.

It is true that the OIE can only publish disease information submitted officially by its members. At times, a proactive approach is required to ensure greater transparency. Mindful of this point, the OIE adopted, at its 69th General Session in May 2001, the text indicating that the Central Bureau Animal Health Information Department shall gather, analyze, and process all of the animal health information available in the OIE member countries, including that which has not been officially sent to the Office. It recognizes that such information may come from expert’s reports, research work, scientific publications, international surveys, communications to other organizations, press articles, health monitoring networks on the Internet (e.g., ProMED), and so on. However, this information will not be distributed by the OIE unless it has been recognized as valid by the delegate of the country concerned.

The OIE searches, in coordination with its Collaborating Centers and partners (the FAO and the WHO), all sources of unofficial information on epidemiological events of significance and pursues all avenues to encourage rapid, transparent, and official reporting by its members. Once this information is obtained and evaluated, it is sent to the corresponding delegate, who is then asked for immediate official confirmation or denial. Thanks to the ever-increasing visibility of this unofficial information and to the negative trade implications of not transparently reporting such events, countries are responding quickly to the OIE with a confirmation or an explanation on the misinformation. During last year, more than 70 percent of the OIE requests resulted in immediate official notifications by the national authorities.

In addition to the WAHIS within the OIE, the OIE also collaborates closely with the FAO and WHO by creating a joint early warning system for major animal diseases and zoonoses, called the Global Early Warning System (GLEWS). The three organizations share the official and unofficial information received and make joint determinations on the extent and type of response required.

While the IHR 2005 of the WHO has recently received much visibility, the animal disease information system of the OIE has been long established and experienced but, nevertheless, is not that well known. Despite its long history and impressive collection and presentation of information, the benefits of the WAHIS have been known primarily by veterinary services and those engaged in international trade of animals and animal products.

There are many similarities between the OIE and the WHO systems. Among others, both systems share a common purpose and scope and a common legal basis in their obligation to notify, they both recognize the sovereign rights of their members, they establish official national focal points, they use official as well as take unofficial data into account, and they both focus on the importance of immediate notification of significant epidemiological events.

However, there are also differences between the two notification systems.

WAHIS is not a stand-alone notification system; it is part of a complex set of obligations and standards to which members must adhere. The WAHID, with the presentation of data in various formats, aside from being an obligation provides great benefits to its members and users at large. The obligations to report are balanced by a series of mechanisms established by the OIE to assist countries in having the basic infrastructure required for a rapid and transparent reporting. Reference laboratories, in order to maintain such status within the OIE, are also required to share their findings with the OIE even in cases where the submitting country may not have done so.

It is the belief of the OIE that, in order to have a global rapid and transparent animal disease reporting system, it must create the proper incentives for all its members to actively participate. Just having a legally binding obligation to report is not likely to solve the problem of lack of reporting by most countries. The OIE has determined that the majority of countries not rapidly reporting the occurrence of notifiable diseases in their territories is because of inability and not unwillingness. Therefore, the OIE is committed to assist in the strengthening of the veterinary infrastructure of these countries unable to report. In order to provide the required assistance, the OIE has established a Global Trust Fund for Animal Health and Welfare,12 which offers capacity-building to its members through several activities.

First, it is worth mentioning the evaluation system for veterinary services (PVS), which is used as a diagnostic tool to assess the strengths and weaknesses of veterinary infrastructures and their ability to comply with their obligations stipulated in the OIE standards. It is conducted by well-trained experts at the request of members. Of course, the assistance cannot be limited to providing diagnostic services, and therefore the OIE is following up in many of the more than 80 countries that have undergone the PVS evaluation, with a gap analysis. This gap analysis is aimed at prioritizing the areas for improvement and assistance to countries in the identification of resources required for such improvements.

The OIE also offers technical assistance in the preparation of focal points, as well as for the development or improvement of regulatory systems, essential to support the legal enforceability of international standards at a national level. Under the Trust Fund, the OIE has also supported the “twinning” program, which is aimed at establishing long-term and more guided collaborative mechanisms between established reference laboratories in developed countries and comparable institutions in developing countries. The ultimate goal is to strengthen the global network of reference laboratories capable of assisting all countries in the diagnosis and characterization of pathogens.

As an additional incentive for rapid and transparent reporting, primarily at the grassroots level, the OIE provides guidance on the establishment of compensation mechanisms. As experienced during the avian influenza H5N1 crisis, it

has been difficult in certain situations to have active and sustained participation by local villagers and small farmers on reporting the presence of sick poultry. At times this is the most important sector in the early reporting of disease. However, it is also the sector most negatively affected by the destruction of the infected and potentially exposed chickens. The OIE believes that, unless there is an adequate compensation mechanism for these individuals, it will be difficult to have a sustained reporting system of emerging diseases.

In order to assist in the response time in cases of serious outbreaks, the OIE has also established a virtual vaccine bank. So far this has been used in cases of serious avian influenza outbreaks, whereby the OIE provides large numbers of vaccines to affected countries when so requested. This mechanism allows countries to begin vaccinating with certified vaccines immediately after the decision is made that vaccination is needed to control the serious outbreak, and without having to wait for the administrative process of securing the funds and identifying the supplier of vaccines. Depending on the country and the situation, the country may then be asked to reimburse the OIE for the vaccines. This service is currently being considered to assist developing countries affected by other significant animal diseases.

In conclusion, the recent avian influenza crisis, as well as other emerging and reemerging disease outbreaks, has shown that disease notification cannot be dealt with in isolation: obligations must be accompanied by incentives and benefits. Unless all countries are in a position to rapidly detect and report significant epidemiological events, animal and public health worldwide will be at risk from the appearance of a pandemic or any other devastating disease. Therefore, countries must be assisted in the strengthening of their animal health governance so that all countries, regardless of their status and trade ability, are in a position to detect and report the emergence of significant diseases. At the national level, there must be a paradigm shift from a traditional focus on protection at the borders and restrictions on trade toward the encouragement of the creation of a global surveillance system, as a global public good, that should benefit all countries and should globally minimize the impact of the emergence of a new disease.

As stated earlier, the OIE publishes the animal disease information only after receiving official confirmation from its delegate. The record shows that members have been very quick to respond positively by officially confirming or denying the validity of information when approached by the OIE with information from unofficial sources. However, on a few recent occasions, the OIE took the responsibility to publish unofficial information on the occurrence of important animal diseases and before it was confirmed by the authorities of the affected country.

In theory, the WHO could legally intervene under IHR 2005, even in cases where the information has not been officially provided by the national authorities. However, it is highly unlikely that this would be done with any frequency in cases where the information is not yet in the public domain. The current inability of

the international community to intervene in serious situations such as the cholera epidemic in Zimbabwe, which is now spreading to neighboring countries, serves as an example.

The international organizations have shown a great spirit of collaboration, evidenced recently in response to the avian influenza crisis. However, to be prepared for future challenges, whether coming from avian influenza or a new emerging disease, the international community as well as leadership at the national level will have to improve and broaden their spirit of interdependence and collaboration.

INCENTIVES AND DISINCENTIVES TO TIMELY DISEASE REPORTING AND RESPONSE: LESSONS FROM THE INFLUENZA CAMPAIGN13

David Nabarro, M.D., C.B.E, F.R.C.P.14

United Nations

International Health Regulations 2005 as the Framework for Action

During the past few years, we have witnessed the agreement and application of the revised International Health Regulations (IHR 2005). This is an important intergovernmental framework and series of instruments for collective responses to infectious disease and other public health threats. The proper implementation of the IHR 2005 depends on the full participation of national authorities and other stakeholders. Some of them question the extent to which systems for global governance on health reflect the interests of poor people and their nations: they question the value of globalized thinking and working.

United Nations System Influenza Coordination

A word on my own involvement in this field: I worked at the WHO in various roles between 1999 and 2005. In September 2005, I was asked by the late J. W. Lee, the then WHO Director-General, and Kofi Annan, the then Secretary-General of the United Nations, to move to New York. My remit was to help different parts of the United Nations (UN) system react to increasing political concern among heads of state and government, particularly from Southeast Asia, about the potential political, societal, and economic impacts of a severe influenza pandemic.

I was asked to establish a temporary mechanism to ensure that the capacities of the whole UN system (technical human health and agriculture bodies, as well

as our full range of social, political, and economic bodies) is made available, in a coherent way, to the governments of our member states.

Agreement on the Science

In 2005, there was broad agreement on the scientific basis of work being undertaken on avian and pandemic influenza: outstanding research questions were also clear. These include a better understanding of risks associated with the movement of highly pathogenic avian influenza among poultry (particularly in ducks); the relative roles of wild birds, trade, and cross-border movements in spreading H5N1 among birds; and the behavioral patterns that increase risks for human infection still needing some work.

The WHO, FAO, and OIE had established clear strategies for national actions to be undertaken: stamping out highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) when identified, through quick and thorough action; reducing the threat to poultry through introducing biosecurity; monitoring wild birds and charting their movements so that, where possible, wild birds that might be infected with this virus could be separated from domestic birds; reducing the risk of human sporadic cases by limiting the degree to which humans would be in contact with infected birds; and then preparing to contain and mitigate the next influenza pandemic when it happens.

This was to be done within the context of two key areas of standards: the OIE Animal Health standards and the revised IHR.

Impetus for Coordinated Implementation

The challenge for us in late 2005 was to ensure that governments gave these strategies the impetus necessary for their implementation, leading to the control of HPAI and preparedness for an influenza pandemic. The technical work had to be taken forward within the momentum of the emerging political environment. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the United States, the European Union, Canada, and Japan took political initiatives as well.

Within the UN System Influenza Coordination Office, we sought to align different international institutions—including the World Bank, the international organizations of the UN, the regional development banks, other international, regional, and local research bodies—to encourage the collective pursuit of international norms and standards, with the specialized organizations (WHO, FAO, and the OIE) charting a path for the rest of the UN system and the myriad of other organizations becoming engaged in work on avian and pandemic influenza.

From the start, most of those who were involved in this work demonstrated unity of purpose and synergy of action. In general, coordination between the bilateral donors—the foundations, national governments, regional bodies, and

international nongovernmental groups (including the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement)—was strong.

The Evolution of an Accountable Movement

We have subsequently sought to identify the incentives that brought many disparate groups to work together. Finance was important, and the partnership has mobilized more than US$3 billion in assistance for avian and human influenza actions between 2005 and 2009. But this, on its own, cannot explain the extent to which national authorities have worked together on these issues. The funds that have been pledged are primarily made available to governments, which have moved comparatively slowly.

An International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza was established as a basis for this cooperation. Other partnerships were organized at the regional level through the European Union, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), ASEAN, and other regional groupings. Few of these partnerships were formal: most had real impact on the alignment and ways of working of their members.

We concluded that most of the groups working together in synergy on this issue recognized its value. They found it both operationally useful and reassuring in a situation where there was considerable political urgency and need for concerted action by institutions. Stakeholders from the public, private, and voluntary sectors have valued the opportunity for coherence, joint working, and participation. They have worked together on disease surveillance, reporting, and response. They have joined together to support the evolution of an inclusive movement that enables hundreds of different stakeholders to feel at home. (WHO’s GOARN is an example of such collaboration: staff from institutions in the network are ready—at short notice—to assist countries with laboratory and epidemiological investigations.) Pandemic preparedness work has moved forward over the past four years thanks to the efforts of this broader movement, which has been tracked through annual global progress reports using information from countries. These reports, which have involved the full range of UN system agencies and the World Bank, have served as the basis for collective accountability. The reports reveal that, over the four-year period, there has been more rapid reporting of HPAI and more effective, sustained responses to outbreaks of the disease in poultry. The OIE is now pursuing the elimination of H5N1 in the next few years.

Factors for Success

The annual reports identify seven factors for success: (1) consistent political commitment; (2) resources and capacity to go to scale in response to a threat; (3) interdisciplinary working (particularly animal health and human health); (4) predictable, prompt, fair, and sustained compensation schemes for those who

lose property or animals as a result of control measures; (5) strong engagement of the public sector, the private sector, and voluntary agencies; (6) clear and unambiguous communication of reliable information (and sharing of uncertainty as appropriate); and (7) the need for a viable and scientific response strategy. Experiences with SARS and other diseases suggest that if information is kept from people they will not feel empowered to be part of the response.

What are the incentives for success? First is the availability of good-quality and accessible information about HPAI outbreaks—based on good mapping of issues, tracking of progress, and risk analysis. Information has been synthesized and made available to those who need it through the efforts of international organizations in response to the needs of their primary clients. WHO provides data to ministries of health and their institutions; and the World Tourism Organization, the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Monetary Fund, and the International Organization for Migration have provided similar services. This interaction enabled people with a stake in pandemic preparations to feel that they are informed and are part of the global effort.

These information networks have had practical implications. Thanks to the link between the World Tourism Organization and WHO, tourism operating companies have immediate access to available information about the location of disease outbreaks that might mean they have to move either their customers or their staff out of harm’s way. Similarly, by knowing what is happening in and around different airports, the International Civil Aviation Organization has helped airport managers to handle these problems. Access to intelligence and its use through agreed procedures facilitates effective preparation: the information itself is an incentive for participation.

A second incentive is the ready availability of instruments and assets needed for effective action. These include the GOARN within WHO and the FAO-OIE Crisis Management Center for Animal Health, which provide a backbone for solidarity and international action. This encourages countries and other stakeholders to be engaged; they know that dependable systems exist that can help them.

A third incentive is the existence of the right legal codes (and means for enforcement) at the country level—for controlling movements of animals, for ensuring compensation when animals have to be killed, and for enabling the consistent nationwide implementation of public health functions (especially in decentralized political systems).

A fourth incentive is the widespread appreciation, among the public, of the pandemic threat and the need to be prepared. Unfortunately, it has not proved easy to sustain the appreciation that animals, and ways in which they are cared for, can pose a risk not only for their own health but also for human health, a risk that can be reduced by changed behavior. The information and compensation needed to encourage behavior changes are often not sufficient. Why do H5N1 deaths in Egypt remain despite the most intense communication campaigns and engagement of all governors in the country?

A fifth incentive is an empowered civil service—people in government who feel that they are in a position to take the initiative in the face of a disease threat. They sometimes do not believe that their own authorities, or international authorities, are working in their interests. This is a challenge. H5N1—or other diseases—will not be controlled through compulsion and sanctions. It does not work. People start to hide, they do not explain, and they do their best to avoid involvement. So it is absolutely essential to build the necessary trust for effective action.

Continuing Challenges

There are a number of continuing challenges for our collective effort to control HPAI caused by the H5N1 virus and to prepare for pandemics.

The first is the lack of adequate systems and capacities for data collection and surveillance, laboratory services, and analysis. This applies to both animal and human health.

The second is the reality that some key groups (in some countries) are not fully engaged into the movement for pandemic preparedness. How do you ensure that workers in the poultry industry see it in their collective self-interest to work together with the nongovernmental organizations, researchers, and governments on control and prevention of HPAI? This requires a continuous effort to build and sustain a movement, which will wither away if it is not persistently supported and kept going.

The third challenge is to maintain trust. Committed professionals from countries in Southeast Asia worked with the Rockefeller Foundation to build the Mekong Basin Disease Surveillance Program over many years. This covers several different disease issues. It has generated trust between technicians across borders, and it has survived and continues to do well, despite occasional difficulties at the ministerial or high political level. Similar systems are being established between Bangladesh, India, and Nepal following their HPAI outbreaks in 2008 and 2009.

We are all involved in this effort to build trust. We should ask ourselves from time to time whether we are contributing to trust as effectively as we could.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we who are involved in this work tend to want to implement the most appropriate (or “right”) actions. These norms must be well publicized, continuously reinforced in a very positive, embracing, and open way, and backed with good-quality literature. They include the following:

-

Strong political leadership. This is the wind in our sails—we move along more easily with it than when it is absent. We have to do our best to sustain the political leadership.

-

A well-structured legal context has value and helps us to move forward with confidence.

-

Engaging all stakeholders—government, private sector, particularly poultry producers, civil society, research groups, the Red Cross, and civil defense.

-

Ensuring that our work leads to benefits for all. It doesn’t have to be a direct linkage, but there has to be some sign that benefits will be there, and they will be shared fairly.

-

Building trust and being skilled at handling mistrust when it exists (because not all relationships are characterized by trust at all times). We need to insure against periods of mistrust that may build up in relationships that are otherwise very good and we have to know that we are able to cope with these periods.

-

Providing compensation for those who are putting themselves out to do extra work, be it tracking cases of H5N1 in poultry or doing extra surveillance for humans that are affected. That doesn’t just apply to individuals; it applies to countries.

Getting the incentives right is worthwhile so that pandemic preparations are successfully put in place. The reward may well be that when the next severe influenza pandemic strikes, millions of people survive who might otherwise be expected to die. That is the ultimate incentive.

COSIVI REFERENCES

Belotto, A., R. Held, D. Fernandes, and E. Alvarez. 2007. Veterinary public health activities in the Pan American Health Organization over the past 58 years: 1949-2007. Veterinaria Italiana 43(4):789-798.

Codex Alimentarius Commission, http://www.codexalimentarius.net/web/index_en.jsp (accessed May 29, 2009).

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) and OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health). 2009. OIE/FAO network of expertise on avian influenza, http://www.offlu.net/ (accessed May 1, 2009).

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health), WHO (World Health Organization), UNSIC (United Nations System Influenza Coordination), UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund), and WB (World Bank). 2008. Contributing to One World, One Health: a strategic framework for reducing risks of infectious diseases at the animal–human–ecosystems interface, http://www.oie.int/downld/AVIAN%20INFLUENZA/OWOH/OWOH_14Oct08.pdf (accessed May 29, 2009).

OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health). 2000. Agreement between the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization and the Office International des Epizooties adopted by PAHO/WHO and the OIE, http://www.oie.int/eng/OIE/accords/en_accord_ops.htm (accessed May 29, 2009).

———. 2004. Agreement between the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the Office International des Epizooties adopted by the FAO and by the OIE, http://www.oie.int/eng/OIE/accords/en_accord_fao_2004.htm (accessed May 29, 2009).

———. 2007. Basic Documents. Forty-sixth Edition. Geneva, World Health Organization, http://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd46/e-bd46.pdf (accessed October 23, 2009).

———. 2008. Contributing to One World, One Health: a strategic framework for reducing risks of infectious diseases at the animal–human–ecosystems interface. Consultation document produced by the FAO, OIE, WHO, UNSIC, UNICEF, and WB, http://www.oie.int/downld/AVIAN%20INFLUENZA/OWOH/OWOH_14Oct08.pdf (accessed May 29, 2009).

———. 2009. Global Early Warning And Response System (GLEWS) for Major Animal Diseases, Including Zoonoses, http://www.glews.net/images/Photos/glews_graph_700.jpg (accessed December 8, 2009).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2006. Global Early Warning System for Major Animal Diseases, Including Zoonoses (GLEWS), http://www.who.int/zoonoses/outbreaks/glews/en/ (accessed May 29, 2009).

———. 2007a. 2007: international health security. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/world-health-day/previous/2007/en/index.html (accessed May 27, 2009).

———. 2007b. A safer future: global health security in the 21st century. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/whr/2007/en/index.html (accessed May 27, 2009).

———. 2007c. International Food Safety Authorities Network (INFOSAN), http://www.who.int/foodsafety/fs_management/infosan_1007_en.pdf (accessed May 1, 2009).

———. 2009a. International Health Regulations, http://www.who.int/topics/international_health_regulations/en/ (accessed May 29, 2009).

———. 2009b. Mediterranean Zoonoses Control Programme (MZCP) of the World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/zoonoses/institutions/mzcp/en/ (accessed May 29, 2009).

———. 2009c. WHO Global Salm-Surv, http://www.who.int/salmsurv/en/ (accessed May 29, 2009).

THIERMANN REFERENCES

OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health). 2006. Appendix to the International Agreement Organic Statutes of the Office of International des Epizooties, http://www.oie.int/eng/OIE/textfond/en_statuts_organiques.htm (accessed May 6, 2009).

———. 2008. Chapter 1.2: criteria for listing diseases. Terrestrial Animal Health Code, http://www.oie.int/eng/normes/mcode/en_chapitre_1.1.2.pdf (accessed May 11, 2009).

———. 2009a. OIE listed diseases, http://www.oie.int/eng/maladies/en_classification2009.htm?e1d7 (accessed May 6, 2009).

———. 2009b. The OIE: about us, http://www.oie.int/eng/OIE/en_about.htm?e1d1 (accessed May 11, 2009).