New Models of Comprehensive Health

Care for People with Chronic Conditions

Chad Boult, M.D., M.P.H., M.B.A.1

Erin K. Murphy, M.P.P.2

SUMMARY

This paper focuses on one of this report’s primary goals: “identifying which population-based interventions can help achieve outcomes that maintain or improve quality of life, functioning, and disability” for adults who have chronic illnesses. It has several goals:

• Identify new models of comprehensive health care that have been reported to improve the functional autonomy or overall quality of chronically ill people’s lives.

• Describe the goals, target populations, and operational features of these models.

• Recommend public health initiatives that would support the refinement and spread of the identified new models of comprehensive health care for chronically ill persons.

In composing this manuscript, we completed:

• Electronic searches of the scientific literature (1987–2011) to identify models of comprehensive health care that have produced significant

![]()

1Professor of Public Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

2Doctoral Student, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

improvements in the functional autonomy or quality of life of chronically ill persons.

• Tabulation of the statistically significant findings of these studies and the models’ relationships to community-based services, such as whether medical and community-based services were coordinated or not.

• Internet searches for reports posted between June 1, 2008, and June 30, 2011, to obtain information about other promising models of chronic care, research about which has not yet been peer-reviewed or published in scientific journals.

From among 15 models of comprehensive care that have been shown to improve life significantly for chronically ill persons, we identified 6 that integrate medical and community-based care:

• Transitional care

• Caregiver education and support

• Chronic disease self-management

• Interdisciplinary primary care

• Care/case management

• Geriatric evaluation and management

In the future, other new models of comprehensive care may also be shown to improve functional autonomy and quality of life.

Public health initiatives that seek to improve the functional autonomy and quality of life of persons with chronic conditions should:

• Explore opportunities to collaborate with organizations that pay for (i.e., insurers) or participate in (i.e., providers) these six successful new models of comprehensive chronic care.

• Use mass media to communicate public messages to chronically ill persons, their families, their health care providers and their local community agencies about the importance of integrating medical and community-based care.

• Evaluate longitudinally the effects of collaborations between medical and community-based care providers on the functional autonomy and quality of life of Americans living with chronic conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Throughout 2011, the American baby boom generation began reaching age 65. The population ages 65 and older will swell to 40 million in 2011,

nearly 55 million by 2020, and more than 70 million by 2030 (CMS, 2009; IOM, 1978, 1987, 2001; Salsberg and Grover, 2006; Shea et al., 2008; U.S. Census Bureau, 2004; Wenger et al., 2003; Wolff et al., 2002). Many older persons, especially the “oldest old,” have chronic conditions and disability, so as the population of older Americans expands, the absolute number with chronic conditions and disability will also rise. Unless scientists make unprecedented breakthroughs in preventing or curing chronic conditions soon, the United States will face growing pandemics of chronic disease and disability throughout the next several decades.

America’s providers of health care and supportive services have not yet developed the capacity to provide high-quality, comprehensive chronic care. Its hospitals, nursing homes, physicians, clinics, and community-based service agencies still operate as uncoordinated “silos” (IOM, 2001), much of the physician workforce is inadequately trained in chronic care (Salsberg and Grover, 2006), and the quality and efficiency of chronic care remain “far from optimal” (IOM, 2001; Salsberg and Grover, 2006; Wenger et al., 2003). In a recent study of health care in seven developed nations, the United States was first (by far) in health care spending but sixth in the quality of care and last in care efficiency, equity, and access (tie). The United States was also last in enabling long, healthy, productive lives for its citizens (Davis et al., 2010).

A successful, long-term, population-based approach to reducing the prevalence and the consequences of chronic illness in the United States would include (a) the primary prevention of chronic diseases, (b) secondary prevention by screening and treatment of preclinical chronic conditions, and (c) tertiary prevention of disability and suffering by effectively treating chronic conditions that are already clinically manifest. Primary preventive initiatives might seek to reduce the incidence of chronic conditions by altering social, cultural, and environmental influences on the population’s diet, physical activity, and exposure to toxins (e.g., tobacco) and infection (e.g., HIV/AIDS). Secondary and tertiary preventive initiatives would seek to treat chronic diseases promptly and effectively through the coordinated efforts of multiple health care providers and community-based supportive services. The ultimate goal of this paper is to identify opportunities for public health agencies to promote such coordination of “medical” and “social” resources to limit the functional and quality of life consequences often borne by Americans with chronic conditions.

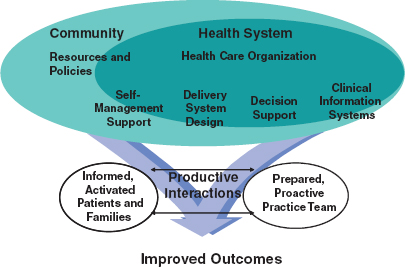

Two overlapping conceptual models help to explicate the complex interacting factors that must be addressed to control the effects of chronic disease in the U.S. population. Not only does the Chronic Care Model (Bodenheimer et al., 2002) focus mostly on improving the ability of the health care delivery system (and its patients and families) to treat chronic illnesses, but it also acknowledges the importance of integrating the delivery

FIGURE B-1 Chronic Care Model.

SOURCE: Reproduced with permission of Wolters Kluwer Law & Business from Wagner, E.H., et al. A survey of leading chronic disease management programs: Are they consistent with the literature? Managed Care Quarterly 7(3):58, 1999.

system with community-based resources and policies. The Expanded Chronic Care Model (Barr et al., 2003) subsumes the Chronic Care Model, but it has a broader perspective. It illuminates the importance of reducing the occurrence of chronic conditions by addressing societal influences on diet, exercise, and other determinants of health. The original, more narrowly focused, Chronic Care Model is better aligned with the secondary and tertiary preventive orientation of this paper (Figure B-1).

Methods

To identify promising new models of comprehensive chronic care, we completed three processes:

• MEDLINE searches of the scientific literature (1987–2011) to identify comprehensive models that have, in high-quality studies, produced significant improvements in the functional autonomy or quality of life of chronically ill persons. We considered a model to be comprehensive if it addresses multiple health-related needs of adults, that is, the model provides care for several chronic conditions, for several aspects of one condition, or for persons receiving care from several health care providers. We excluded models that

addressed a single treatment for one condition, such as innovations in conducting cataract surgery or managing one medication. We rated study designs as of high quality if they were clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses. To cover this 24-year span, we extended two literature searches that we had conducted previously. The first, conducted in 2007, had identified promising models to help inform the Institute of Medicine’s 2008 recommendations for reshaping the U.S. workforce of health professionals to better care for the aging American population (IOM, 2008). The second, conducted in mid-2008, was an update of the 2007 search (Boult et al., 2009). For purposes of this report, we extended our previous searches to include information available through June 2011.

• Tabulation of the statistically significant findings of these studies and the models’ relationships to community-based services (i.e., whether medical and community-based services were coordinated or not). Because of the considerable heterogeneity of target populations and care processes included in the identified models—and the methods used to study them—we were not able to conduct meta- analyses or systematic reviews of the models’ positive and negative effects.

• Internet searches for reports posted between June 1, 2008, and June 30, 2011, to obtain information about other promising models of chronic care, research about which has not yet been peer-reviewed or published in scientific journals.

PROMISING MODELS OF COMPREHENSIVE CHRONIC CARE

Numerous new models of care for people with chronic conditions have been proposed, created, tested, and promoted in recent years. Some are primarily innovations in paying for care—such as capitated models, like Medicare Advantage and Special Needs Plans; shared savings models, like accountable care organizations; and pay-for-performance models. Such financial models are designed to drive improvements in the delivery, quality, and outcomes of care, but they do not specify how care should be provided. Other new models are primarily innovations in the provision of care, many of which also require changes in payment in order to be financially sustainable.

Our searches and this report focus on the latter, that is, on new models of providing care for people with chronic health conditions, emphasizing those that credible scientific evidence suggests can improve patients’ quality of life or functional autonomy. The following two sections describe 17 new models that address some or all components of the Chronic Care

Model and appear promising. A brief description of each model outlines its goals, target population, methods of operation, and the currently available evidence of its effectiveness in improving quality of life and functional autonomy—as well as in reducing the use and cost of health services. Innovative models that reduce the cost of health care (or at least do not increase it) are inherently more likely than those that incur additional costs to be adopted widely in today’s cost-conscious environment. When appropriate, we note how these models incorporate community-based services.

The first section (A) describes 15 new models in which credible scientific evidence published in peer-reviewed journals has shown statistically significant improvements in chronically ill patients’ functional autonomy or quality of life. A table that summarizes this evidence follows section A. The second section (B) describes new two new models that may improve functional autonomy or quality of life, but peer-reviewed evaluations of these outcomes are lacking.

Section A: Comprehensive models of health care reported in peer-reviewed journals to produce statistically significant improvements in the quality of life or the functional autonomy of persons with chronic conditions.

MEDLINE reviews of the scientific literature from January 1987 through June 2011 identified 15 successful models of comprehensive care for persons with chronic conditions (Models A-O in Table B-1).

Nine of these models are based on either interdisciplinary primary care teams (Model A) or community-based supplemental health-related services that enhance traditional primary care (Models B-I).

Three successful models address the challenges that accompany care transitions, including one that facilitates transitions from hospital to home (Model J) and two that provide acute care in patients’ homes, either in lieu of hospital care (Model K) or following brief hospital care (Model L).

Three institution-based models have improved care for residents of nursing homes (Model M) and for patients in acute care hospitals (Models N and O).

Note: Aside from meta-analyses and reviews, this paper summarizes only peer-reviewed studies that found that new models improved outcomes; it excludes “negative” studies. Thus, the evidence reported here should be construed primarily as preliminary findings, not as complete summaries of positive and negative studies of the models of care.

Below we summarize the models’ goals, target populations, operations, and evidence of effectiveness in improving quality of life and functional autonomy—as well as in reducing the use and cost of health services.

When appropriate, we note how these models incorporate community-based services.

Interdisciplinary Primary Care Models (Model A)

Each of these models (e.g., IMPACT, Guided Care, GRACE, PACE and others) strives to enhance chronically ill patients’ functional autonomy and quality of life. In each, comprehensive care is provided by interdisciplinary teams composed of a primary care physician and one or more other co-located health care professionals, such as nurses, social workers, nurse practitioners, or rehabilitation therapists, who communicate regularly with each other. Many of these models coordinate medical care with supportive services provided by community-based agencies.

A related, recently popularized model is the patient-centered medical home (PCMH), which targets all patients in a primary care practice, including those with and those without chronic conditions (Berenson et al., 2011). Using interdisciplinary teams and electronic information technology, medical homes provide:

• Empanelment—each patient is assigned to a primary care provider who is responsible for that patient’s care over time.

• Access—patients have access to health care 24/7/365 through same-day office visits and communication by telephone, email, and Internet.

• Diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive services for addressing most of its patients’ needs for acute and chronic health care.

• Coordination of all providers of care, especially through transitions between sites of care.

• Support for patient self-management of their health-related conditions.

• Clinical decision making that incorporates patients’ goals, values, preferences, and culture.

• Periodic review of patient records to identify patients at high risk and those with gaps in their care.

• For high-risk patients, team-based comprehensive health assessment, evidence-based comprehensive care planning, proactive monitoring, transitional care, coordination of health care and community services, and support for family caregivers.

Although processes are available through which practices can be recognized as medical homes (e.g., the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s PPC-PCMH recognition, levels 1-3), there is considerable heterogeneity among medical homes. For example, some medical homes are self-contained, that is, all staff members are co-located at the primary care practice, whereas others involve collaboration between practice and staff members who are located in community-based agencies. Two empirical

studies of medical homes have undergone peer review and have been published in credible scientific journals; both were conducted in medical homes in which the health care teams were co-located in primary care practices. Obviously, studies of the effects of one type of medical homes may not apply to other types.

As shown in the table, most interdisciplinary primary care models have improved patients’ quality of life and functional autonomy. Some types of teams have significantly reduced patients’ use of selected health services. For most of these models, however, the available evidence of success is limited to a single randomized trial. Only teams focused on heart failure have improved patients’ survival and have been evaluated in enough studies to allow a meta-analysis, which reported significant reductions in hospital admissions and total health care cost (Arean et al., 2005; Battersby et al., 2007; Beck et al., 1997; Bernabei et al., 1998; Boult et al., 2008, 2011; Boyd et al., 2008, 2010; Callahan et al., 2006; Chavannes et al., 2009; Counsell et al., 2007, 2009; Fann et al., 2009; Gilfillan et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2000; Kane et al., 2006; Khunti et al., 2007; McAlister et al., 2004; Rabow et al., 2004; Reid et al., 2010; Rosemann et al., 2007; Sylvia et al., 2008; Unützer et al., 2002, 2008; van Orden et al., 2009; Windham et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2006).

Care/Case Management (Model B)

The overarching goal of care management (CM) programs is to improve the efficiency of health care by optimizing chronically ill patients’ use of medical services. In most CM programs, a nurse or a social worker works as a care manager to help chronically ill patients and their families assess problems, communicate with health care providers, and navigate the health care system. The degree to which care managers coordinate patients’ medical care with community-based supportive services varies from program to program. Care managers are usually employees of health insurers or capitated health care provider organizations. CM has been shown fairly consistently to improve patients’ quality of life, less so their functional autonomy. Its effects on the use and cost of health services are mixed (Alkema et al., 2007; Anttila et al., 2000; de la Porte et al., 2007; Ducharme et al., 2005; Gagnon et al., 1999; Inglis et al., 2006; Kane et al., 2004b; Markle-Reid et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2004; Ojeda et al., 2005; Peters-Klimm et al., 2010; Rea et al., 2004; Vickrey et al., 2006).

Disease Management (Model C)

Disease management (DM) programs attempt to improve the quality and outcomes of health care for people who have a particular chronic

condition (e.g., diabetes, heart failure). DM programs (now often called population management programs) supplement primary care by providing patients with support and information about their chronic conditions, either in writing or by telephone. Health insurers or capitated provider organizations contract with DM companies that employ nurses or other trained technicians to provide patients with health education and instructions for self-monitoring, following treatment guidelines, and participating in medical encounters. Few DM programs engage community-based services. One review that examined DM for heart failure, coronary disease, and diabetes reported no significant effect on any of the relevant outcomes. A meta-analysis of heart failure programs, however, reported that DM was associated with significantly fewer hospital admissions. A subsequent randomized controlled trial (RCT) found that DM for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients was associated with better quality of care, better quality of life, improved COPD-related survival, and a shift from unscheduled to scheduled visits to physicians. Another RCT showed significant improvements in the quality of life and functional autonomy, as well as reduced use of hospitals by patients with angina (Holtz-Eakin, 2004; Sridhar et al., 2008; Whellan et al., 2005; Woodend et al., 2008).

Preventive Home Visits (Model D)

Preventive home visits are multidimensional, in-home assessments of older people performed by nurses, physicians, or other visitors that generate recommendations to primary care providers. Their goals are to improve the treatment of existing health problems, to prevent new ones, and thereby to enhance patients’ quality of life and functional autonomy. Some of these programs integrate community-based supportive services with medical services, whereas others focus entirely on medical care. Meta-analyses have found that these programs can reduce disability, mortality, and nursing home admissions, especially when they target relatively healthy “young-old” persons, include a clinical examination with the initial assessment, or offer extended follow-up. The heterogeneity of the programs and populations studied creates considerable uncertainty about the generalizability of these results (Elkan et al., 2001; Huss et al., 2008; Stuck et al., 2002).

Outpatient Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) and Geriatric Evaluation and Management (GEM) (Model E)

Outpatient CGA and GEM are supplemental services designed to improve the quality of life and functional autonomy of high-risk older persons. CGA and GEM programs are usually staffed by interdisciplinary teams of physicians, nurses, social workers, and, in some programs, also by rehabilitation

therapists, pharmacists, dieticians, psychologists, or clergy. Most programs are sponsored by hospitals, academic health centers, or capitated health care provider organizations, such as the Veterans Administration. The programs identify the patient’s health conditions, develop treatment plans for those conditions, and (in GEM) implement the treatment plans over weeks to months. They obtain information from and communicate their findings and recommendations to their patients’ established primary care providers, and they include community-based supportive services in their plans and recommendations. In about half the RCTs that measured patients’ quality of life and functional autonomy, outpatient GEM improved these outcomes. However, outpatient GEM does not consistently reduce the use or the cost of health care services (Boult et al., 2001; Burns et al., 2000; Caplan et al., 2004; Cohen et al., 2002; Epstein et al., 1990; Keeler et al., 1999; Nikolaus et al., 1999; Phibbs et al., 2006; Reuben et al., 1999a; Rubenstein et al., 2007; Rubin et al., 1993; Silverman et al., 1995; Toseland et al., 1996).

Pharmaceutical Care (Model F)

Pharmaceutical care is advice about medications provided by pharmacists to patients or interdisciplinary care teams. Pharmaceutical care programs aim to improve the use of medications and thereby to improve patients’ health. Depending on the program, pharmacists’ recommendations may be focused on a site of care (e.g., nursing home, patient’s home), on a specific disease (e.g., heart failure, hypertension), or on specific patient profiles (e.g., patients receiving GEM, patients taking several medications). Such programs have been shown to improve appropriate prescribing, medication adherence, disease-specific outcomes, and, in some cases, survival. Quality of life has not been improved consistently, but some programs have reduced the use of hospitals (Crotty et al., 2004; Gattis et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2006; López et al., 2006; Spinewine et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2006)

Chronic Disease Self-Management (Model G)

Chronic disease self-management (CDSM) programs are structured, time-limited interventions designed to provide health information and empower patients to assume an active role in managing their chronic conditions, often through the use of community-based services. Their ultimate goal is to improve patients’ quality of life and functional independence. Some programs, led by health professionals, focus on managing a specific condition, such as stroke, whereas others, led by trained lay persons, are aimed at addressing chronic conditions more generically. Most are sponsored by health insurers or community agencies; they communicate with

primary care providers primarily through their clients. Numerous randomized controlled trials and a meta-analysis report that CDSM leads to better quality of life and greater functional autonomy. Several studies also report that CDSM reduces the use and cost of health services (Chodosh et al., 2005; Clark et al., 1992, 2000; Fu et al., 2003; Hughes et al., 2004; Janz et al., 1999; Leveille et al., 1998; Lorig et al., 1999; Maly et al., 1999; Swerissen et al., 2006; Wheeler et al., 2003).

Proactive Rehabilitation (Model H)

Proactive rehabilitation is a relatively new supplement to primary care in which rehabilitation therapists provide outpatient assessments and interventions designed to help physically disabled older persons to maximize their functional autonomy, quality of life, and safety at home. The few studies that have evaluated this intervention have consistently shown beneficial effects on physical function. In a quasi-experimental study, subjects receiving home restorative care had a significantly greater likelihood of remaining at home. Reductions in hospital, emergency department, or home care use have occurred less consistently (Gill et al., 2002; Gitlin et al., 2006a, 2006b; Griffiths et al., 2000; Mann et al., 1999; Tinetti et al., 2002).

Caregiver Education and Support (Model I)

Caregiver education and support programs are designed to help informal/family caregivers to enhance the well-being of their loved ones with chronic conditions. Led by psychologists, social workers, or rehabilitation therapists, these programs provide varying combinations of health information, training, access to professional and community resources, emotional support, counseling, and information about coping strategies. There is strong evidence, both in randomized studies and in two meta-analyses, that programs that support the caregivers of patients with dementia delay nursing home placement significantly, particularly programs that are structured and intensive. Similarly, all three studies, including one meta-analysis, that examined the effect of caregiver programs on patients’ quality of life showed significant benefit (Brodaty et al., 2003; Kalra et al., 2004; Mittelman et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2004; Pinquart and Sörensen, 2006; Teri et al., 2003).

Transitional Care (Model J)

Most transitional care programs are designed to facilitate smoother and safer patient transitions from a hospital to another site of care (e.g., another health care setting, home), ultimately resulting in fewer readmissions to

hospitals. Transitional care is typically provided by a nurse or an advance practice nurse (APN), who begins by preparing the hospitalized patient and informal caregiver for the coming transition. Depending on the program, the nurse, sometimes known as a “transition coach,” may participate in the discharge planning, teach the patient about self-care (particularly about the use of medication), coach the patient and informal caregiver about communicating with health professionals effectively, visit the patient soon after discharge, and monitor the patient for days to weeks after the transition. A patient’s transitional plan may include community-based resources, such as home health care, meals on wheels, or subsidized handicapped transportation. Most transitional care programs have been sponsored by health insurers or capitated health care provider organizations. Transitional care is consistently successful in improving patients’ quality of life and reducing their readmissions to hospitals (Coleman et al., 2006; Naylor et al., 2004; Phillips et al., 2004).

Hospital-at-Home (Model K and Model L)

Hospital-at-Home (HaH) programs provide care for a limited number of acute medical conditions that have been traditionally treated in acute care hospitals. The goal is to resolve the acute condition more safely, comfortably, and inexpensively than inpatient hospital care can achieve. In the “substitutive” type of HaH (Model K), care is provided in the home in lieu of hospital care. After initial assessment confirms that a patient requires hospital-level treatment but can be treated safely at home, the patient returns home and is treated by an HaH team that includes a physician, nurses, technicians, and rehabilitative therapists. Tests and treatments that would otherwise be provided in a hospital are delivered in the home until the patient has recovered. Substitutive models differ in the intensity of the care they provide, particularly by physicians. Most models have improved patients’ quality of life and reduced inpatient utilization and health care costs.

“Early discharge” models of HaH (Model L) provide acute care in the home following a brief hospitalization. In early discharge HaH models, after a patient’s medical condition has stabilized in the hospital, the patient returns home and is treated there by an HaH team consisting chiefly of nurses, technicians, and rehabilitative therapists. Early discharge models have been evaluated following surgery, such as joint replacement, and for such medical conditions as rehabilitation after stroke. Most of these programs have reduced inpatient utilization but have had few measurable effects on quality of life or functional autonomy (Board et al., 2000; Caplan et al., 1999, 2005; Jones et al., 1999; Leff et al., 2005, 2006; Martin et al., 1994; Melin and Bygren, 1992; Ricauda et al., 2004, 2005, 2008; Rodgers

et al., 1997; Rudd et al., 1997; Tibaldi et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 1999, 2002).

Care in Nursing Homes (Model M)

Several new models of care have been developed to improve the lives of nursing home residents. Most rely on primary care provided by an APN or physician assistant (PA) employed by an insurance company, the nursing home, or a provider organization. The APN or PA evaluates the resident every few weeks, trains the nursing home staff to recognize and respond to early signs of deterioration, assesses changes in the resident’s status, communicates with the resident’s family, and treats straightforward medical conditions at the nursing home (rather than admitting the resident to a hospital). The APN or PA usually works in partnership with a physician skilled in long-term care and who provides supplemental care as needed. Most such programs do not include community-based agencies. One model has been shown to improve residents’ quality of life, and one improved residents’ functional autonomy. Several models have reduced the frequency of residents’ visits to hospitals and emergency departments (Kane and Homyak, 2003; Kane et al., 1989, 2003, 2004a, 2005, 2007; Morrison et al., 2005; Reuben et al., 1999b).

Prevention and Management of Delirium (Model N)

Special programs for hospitalized older patients have been designed to preserve quality of life and functional independence by reducing the effects of delirium. These programs usually involve training hospital staff, implementing preventive measures and routine screening for delirium, using evidence-based guidelines to address risk factors for delirium, assessing its causes, and treating it promptly when it appears. Studies of such programs have reported reductions in the incidence and complications of delirium, faster resolution of it, and shorter hospital stays, all of which are associated with better quality of life and greater recovery of functional abilities. Trials of delirium management programs have demonstrated fewer benefits, suggesting that programs designed to prevent delirium are more beneficial than those designed to treat it (Cole et al., 1994; Inouye et al., 1999; Leslie et al., 2005; Lundström et al., 2005, 2007; Pitkala et al., 2008; Rizzo et al., 2001).

Comprehensive Inpatient Care (Model O)

Comprehensive hospital care models include interdisciplinary geriatric consultation teams, acute care for elders (ACE) units, comprehensive

pharmacy programs, inpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), and inpatient geriatric evaluation and management (GEM) units. These interventions seek to improve the quality and outcomes of hospital care for chronically ill patients by preventing adverse events, facilitating transitions back to the community, and reducing readmissions to the hospital. An ACE unit is a medical ward with an elder-friendly environment, care by an interdisciplinary geriatric team, a philosophy of patient activation, and early discharge planning. A 1993 meta-analysis of eight studies concluded that inpatient consultation teams preserve older inpatients’ cognition and ability to return to their own homes, but they have no effect on functional autonomy, survival, or hospital readmissions. Three RCTs and one quasi-experimental study suggest that ACE units may improve inpatients’ health and functional autonomy without consistently affecting their survival or their use or cost of health services. A meta-analysis reported that inpatient CGA and GEM significantly improved patients’ functional autonomy (after 12 months) and survival (after 6 months). Researchers in Sweden found that a comprehensive inpatient pharmacy program reduced adverse drug events and readmissions in older patients (Asplund et al., 2000; Counsell et al., 2000; Gillespie et al., 2009; Landefeld et al., 1995; Marcantonio et al., 2001; Mudge et al., 2006; Saltvedt et al., 2002, 2004; Stuck et al., 1993).

In Table B-1, an up-arrow indicates that a model has significantly improved an outcome. The fractions in parentheses indicate the number of studies that assessed an outcome (denominator) and the number that reported significantly positive effects (numerator). Asterisks indicate that at least one meta-analysis reported a significantly positive effect. Red letters highlight increases in the use or costs of certain health care services, some [of] which may be desirable, such as increases in outpatient visits that lead to fewer hospital admissions.

Section B: Comprehensive models of health care claimed in non-peer-reviewed reports to improve the quality of life or the functional autonomy of persons with chronic conditions.

Collaborative Medical Homes

Collaborative medical homes are primary care practices that collaborate with community-based agencies—rather than expanding their intramural staff and operations—to provide comprehensive medical home services to their patients. Examples described on the following pages include Community Care of North Carolina and the Vermont Blueprint for Health.

Several reports of the effects of collaborative medical homes have been publicized recently. However, these reports have provided few scientific details, and their analyses have not been subjected to scientific peer review.

These reports have value, but they are limited by various combinations of (1) incomplete descriptions of the population served and the medical home services provided, (2) dissimilar (or no) comparison groups, (3) small sample sizes, (4) weak analytic approaches, (5) inappropriate statistical testing, and/or (6) selective reporting of only favorable results.

Community Care of North Carolina (CCNC) consists of 14 regional community health networks supported by a statewide administrative infrastructure. In each network, physician practices (medical homes) collaborate with hospitals, local health departments, and social service agencies to provide comprehensive care—including care management—for the majority of North Carolina’s Medicaid enrollees. Most CCNC case managers are based in community settings. The CCNC program’s effects on quality of life and functional independence have not been reported, but a management consulting firm estimates that the CCNC saved the state of North Carolina up to $300 million through reductions in hospitalizations and emergency room use (Community Care of North Carolina, 2010, 2011; Steiner et al., 2008).

The Vermont Blueprint for Health is one of eight state-based programs participating in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration. In this model, each advanced primary care practice (medical home) is supported by a community health team and a health information technology (HIT) infrastructure. Community health teams, composed of registered nurses, social workers, and behavioral health counselors, coordinate care; coach patients in self-care; ensure that they are up to date with appointments, tests, and prescriptions; and make referrals for mental health and substance abuse care. Public health specialists guide the community health teams toward meeting the goals of public health campaigns. Practices receive their usual fee-for-service health insurance payments, plus additional per person per month fees, which vary depending on the practice’s degree of attainment of patient-centered medical home standards. The effects of the Vermont Blueprint for Health on patients’ quality of life and functional autonomy have not been assessed, but preliminary intramural analysis of pre-post data suggest that the program has reduced hospitalizations and emergency room visits and generated an 11.6 percent cost savings in one community (Bielaszka-Du Vernay, 2011).

Complex Clinics

Complex clinics are multidisciplinary primary care practices that provide comprehensive care for people with complicated medical and psychosocial conditions. Some complex clinics treat only complex patients, and others treat the full range of patients, some of whom have complex needs. Such clinics have been launched and evaluated in several U.S. locations

TABLE B-1 Summary of Evidence on Outcomes of 15 Models of Comprehensive Chronic Care

| Model | Coordination with community- based services |

Studies | Quality of life | Functional autonomy |

Survival | Use/cost of health services |

| A. Interdisciplinary primary care |

X | 1 meta-analysis 2 reviews 10 RCTs 6 QE studies 1 XS time series |

↑ (10/11) |

↑ (6/9) |

↑ (2*/14) |

Lower use (12*/15) Lower costs (3*/11) Higher costs (1/7) |

| B. Care/case management |

X | 13 RCTs 1 QE study |

↑ (7/9) |

↑ (1/4) |

↑ (4/8) |

Lower use (6/10) More use (4/10) Lower costs (1/3) |

| C. Disease management | 1 review 1 meta-analysis 2 RCTs |

↑ (2/3) |

↑ (1/1) |

↑ (1/3) |

Lower use (2*/3) |

|

| D. Preventive home visits | 3 meta-analyses | NA | ↑ (2*/3) |

↑ (3*/3) |

Lower use (2*/3) |

|

| E. Comprehensive geriatric assessment, Geriatric evaluation and management |

X | 10 RCTs 1 QE |

↑ (7/10 |

↑ (6/11) |

↑ (1/9) |

Lower use (4/9) More use (3/9) Higher costs (1/5) |

| F. Pharmaceutical care | 6 RCTs | NA | ↑ | Lower use | ||

| (1/3) | (2/5) | (2/3) | ||||

| G. Chronic disease self-management |

X | 1 meta-analysis 10 RCTs |

↑ (8*/9) |

↑ (7*/7) |

NA | Lower use (4/5) Lower costs (1/1) |

| H. Proactive rehabilitation | 4 RCTs 1 QE study |

↑ (2/3) |

↑ (4/5) |

↑ (1/3) |

(2/4) More use (1/4) |

| I. Caregiver education and support |

X | 2 meta-analyses 3 RCTs |

↑ (3*/3) |

↑ (1/2) |

ND (1/1) |

Lower use (3*/4) Lower costs (1/1) |

| J. Transitional care | X | 1 meta-analysis 2 RCTs |

↑ (2*/2) |

ND (1/1) |

↑ (1/2) |

Lower use (2/3) Lower costs (3*/3) |

| K. Substitutive hospital-at-home |

5 RCTs 1 QE study |

↑ (5/6) |

↑ (1/6) |

ND (5/5) |

Shorter LOS (3/3) Lower costs (5/5) |

|

| L. Early discharge hospital-at-home |

4 RCTs | ↑ (1/4) |

↑ (1/4) |

ND (3/3) |

Lower use (4/4) |

|

| M. Care in nursing homes |

5 QE studies 1 RCT |

↑ (1/1) |

↑ (1/3) |

↑ (1/2) |

Lower use (4/4) More use (2/4) Lower costs (1/1) |

|

| N. Prevention and management of delirium |

4 RCTs 2 QE studies |

↑ (5/5) |

↑ (1/1) |

↑ (1/3) |

Shorter LOS (2/3) Lower costs (1/3) |

|

| O. Comprehensive inpatient care |

2 meta-analyses 6 RCTs 1 QE study |

(3*/4) | (5*/6) | (3*/7) | Lower use (3/9) More use (1/8) |

NOTE: * includes meta-analysis; ↑ = better outcome; LOS = length of stay in hospital; NA = not assessed; ND = no difference; QE = quasi-experimental, RCT = randomized controlled trial, XS = cross-sectional.

Fractions: numerator = number of studies showing significant difference, denominator = number of studies in which this outcome was assessed.

in recent years, and reports in the lay press assert that they have reduced chronically ill patients’ use of emergency departments and hospitals, thereby reducing the overall cost of their health care (Gawande, 2011). Information that underlies such reports has been published in several trade publications, which are summarized here. As detailed below, these non-peer-reviewed reports tend to claim 20–30 percent savings for Medicare, but they do not report the level of detail that would be necessary to make independent determinations of the validity of these claims.

Examples of complex clinics that treat only complex patients:

• Boeing’s Intensive Outpatient Care Program (IOCP) in Puget Sound, WA

The IOCP aims to improve the quality of health care while reducing the costs of care for patients predicted to incur high health care costs. For each patient, a registered nurse/case manager conducts a comprehensive evaluation, develops a care plan, promotes patient self-management of chronic diseases, and confers with the patient’s primary care physician through regular “huddles.” IOCP patients’ scores on functional independence and depression improved from baseline, but these scores were not compared with a control group. Preliminary results also suggest that the IOCP achieved a 20 percent reduction in spending compared with a propensity-matched control group, largely as a result of reduced use of emergency departments and hospitals. This difference was not statistically significant (Milstein and Kothari, 2009).

• Four Medical Home Runs

Four practices were identified as medical home runs if health insurers reported that they had achieved similar quality of care compared with their local peers and at least 15 percent average annual per capita reductions in health care costs. All four models provided chronically ill patients with intensive, individualized care management and coordination with selected specialists (Milstein and Gilbertson, 2009).

• The Citywide Care Management System in Camden, NJ

The Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers (CCHP) developed the Citywide Care Management System (CCMS) to target “super-utilizers” of emergency departments and hospitals. A primary care team composed of a family physician, a nurse practitioner, a community health worker, and a social worker seeks to integrate solutions to patients’ unmet medical and social needs and thereby

to reduce their use of acute care services. CCMS social workers, for example, help patients apply for public benefits, find housing, enroll in substance abuse counseling, manage legal issues, and arrange transportation to medical appointments. An internal pre-post analysis reports that CCMS patients had fewer emergency visits and hospitalizations, resulting in a 56 percent reduction in overall spending (Brenner, 2009; Green et al., 2010).

• The Special Care Center in Atlantic City, NJ

AtlantiCare, the largest local health care provider in southern New Jersey, developed the Special Care Center (SCC) as a comprehensive clinic for patients with chronic conditions. The SCC is staffed by medical assistants and licensed practical nurses acting as health coaches who meet with patients individually and coordinate their care with physicians. Mental health and pharmacy staff also collaborate with the care team. Internal data suggest that compared with a similar AtlantiCare population that received usual care, SCC patients had better rates of cholesterol control, drug compliance, smoking cessation, and patient satisfaction, as well as fewer hospitalizations and emergency visits and shorter lengths of stay (Blash et al., 2010).

• The CareMore Model

The CareMore model, implemented by a Medicare Advantage plan in Southern California, involves intensive case management for frail and chronically ill members and close monitoring of nonfrail members to prevent decline. CareMore patients undergo a comprehensive physical exam with a detailed medical history and are then triaged to appropriate chronic disease management teams. A nurse practitioner is the focal point of the care team, which relies on health information technology and remote monitoring to track patients’ status. An “extensivist” physician supervises CareMore patients in the hospital and ensures smooth transitions to posthospital care. CareMore also refers its members to several community-based services to supplement their medical care, including transportation and fitness programs, home and respite care, and caregiver assistance. CareMore reports a 15 percent reduction in health care costs compared with regional averages, as well as superior diabetes control and lower rehospitalization rates compared with national averages (Reuben, 2011).

Examples of complex clinics that treat complex and noncomplex patients:

• The Commonwealth Care Alliance’s Senior Care Options program

Senior Care Options, a product of the Community Care Alliance in Boston, is a dual-eligible special needs plan that serves primarily older adults receiving Medicare and Medicaid—the dual eligible population. With capitated payments from Medicare and Medicaid, Senior Care Options provides clinical care in a variety of settings. A multidisciplinary team of nurse practitioners, geriatric social workers, and other clinic- and community-based staff conducts comprehensive assessments and arranges a wide array of services, including transportation and escorts to appointments, to promote independent functioning by patients with chronic conditions. Unpublished data suggest that Senior Care Options improves the quality of care for chronically ill patients and reduces their use of hospitals and nursing homes, as well as their overall health care costs (AHRQ; Meyer, 2011).

• Clinica Family Health Services

Clinica Family Health Services is a community health center that serves a primarily low-income, Hispanic population near Denver, Colorado. It adopted the patient-centered medical home model to improve access to care for its patients, half of whom are uninsured. “Pods” of providers, including physicians, nurses, medical assistants, case managers, and behavioral health specialists, coordinate care and share responsibility for patients. Their work environment is open and accessible to facilitate communication. Clinica reports improved access to care and continuity of care, as well as better rates of immunizations and control of diabetes and hypertension compared with the average for Medicaid programs (Bodenheimer, 2011).

CONCLUSION

Fifteen new models of comprehensive chronic health care have been shown by at least one high-quality research study to be capable of making significant improvements in chronically ill patients’ quality of life and functional autonomy. Six of these new models integrate community-based supportive services with medical care, making them attractive partners for collaboration with community-based public health initiatives:

• Transitional care

• Caregiver education and support

• Chronic disease self-management

• Interdisciplinary primary care

• Care/case management

• Geriatric evaluation and management

High-quality scientific evidence indicates that the first three—transitional care, caregiver education and support, and chronic disease self-management—may also reduce the use and cost of health care, which may facilitate their widespread dissemination in the future. The economic effects of the other three new models—interdisciplinary primary care, care/case management, and geriatric evaluation and management—are less clear and consistent. Additional new models of comprehensive chronic care (e.g., collaborative medical homes, complex clinics) may be shown in the future to improve chronically ill persons’ functional autonomy and quality of life, but high-quality scientific evidence of such effects is currently lacking.

PROPOSALS

Public health initiatives that seek to improve the functional autonomy and quality of life of persons with chronic conditions should:

1. Explore opportunities to collaborate with organizations that pay for (i.e., insurers) or participate in (i.e., providers) these six successful new models of comprehensive chronic care. For example, a local public health department might broker collaborative agreements between local insurers that fund transitional care programs and local community-based service agencies, such as meals on wheels and handicapped transportation providers, who assist people who are making transitions from hospital to home. Similarly, state health departments might facilitate ongoing cooperative agreements between primary care practices that wish to upgrade their services to become medical homes and state-supported, community-based chronic disease self-management courses, caregiver support programs, and Area Agencies on Aging, all of which provide important medical home services. Facilitating such integration of medical and community-based supportive services is one of the foremost challenges identified by the Chronic Care Model and the Expanded Chronic Care Model for improving the outcomes of chronic care. Public health agencies, which fund or provide many community-based services, are ideally positioned to help bridge the gaps between these silos.

2. Use mass media to communicate public messages to chronically ill persons, their families, their health care providers, and their local community agencies about the importance of integrating medical and community-based care. Many people (and their families) who live with chronic conditions are unaware of the medical care models and/or the community-based services that could help improve their functional independence and the quality of their lives. As a result, they settle for “routine” health care, which is often fragmented and inattentive to mental health, self-management, family caregivers, community-based services, and patients’ priorities for independence and quality of life. Similarly, chronically ill people may not take advantage of available resources, such as community-based transportation, meals, and volunteer chore programs. Public health organizations could partner with disability and disease-specific public advocacy groups—such as the American Diabetes Association, the Alzheimer’s Association—to fund and provide informational communications through social and traditional media, such as Facebook, Twitter, print, television, radio and billboards. Messages could alert chronically ill persons and their families to the availability of local medical providers that coordinate their efforts with community-based services, as well as to the direct accessibility of community-based services that could meet their needs.

3. Evaluate longitudinally the effects of collaborations between medical and community-based care providers on the functional autonomy and quality of life of Americans living with chronic conditions. The concept of integrating medical and community-based services for the benefit of people with chronic illnesses has considerable appeal. There are formidable obstacles, however, to the practical implementation of this concept, not the least of which is the absence of credible scientific data supporting the value of such integration. We do not know, for example, whether the additional costs incurred by integrating community-based services into a primary care practice, most of which are driven by additional staff time, can be justified by better quality of life or greater functional independence for the practice’s chronically ill patients. We also do not know whether such integration would increase, decrease, or have no effect on the overall costs of comprehensive care for such patients. Rhetorical arguments about the logic and wisdom of service integration can raise awareness, but they are unlikely to evoke difficult change without compelling supportive evidence. National public health entities, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, could facilitate the research necessary to provide such evidence. The CDC could sponsor, for example, a suite of demonstration

projects designed to measure multiple effects of different approaches to service integration on the lives of Americans living with chronic conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contributions to this report made by the IOM committee and staff, the myriad innovators and researchers who developed the models and compiled the evidence summarized here, and Ms. Taneka Lee, who word-processed the manuscript. The paper is the result of collegial, iterative collaboration by the committee, the IOM/NAS staff, and the authors. We hope that it succeeds in helping to improve the lives of millions of Americans who live with chronic conditions.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange. http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/ (accessed August 9, 2011).

Alkema, G.E., K.H. Wilber, G.R. Shannon, and D. Allen. 2007. Reduced mortality: The unexpected impact of a telephone-based care management intervention for older adults in managed care. Health Services Research 42(4):1632–1650.

Anttila, S.K., H.S. Huhtala, M.J. Pekurinen, and T.K. Pitkäjärvi. 2000. Cost-effectiveness of an innovative four-year post-discharge programme for elderly patients—prospective follow-up of hospital and nursing home use in project elderly and randomized controls. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 28(1):41–46.

Arean, P.A., L. Ayalon, E. Hunkeler, E.H. Lin, L. Tang, L. Harpole, H. Hendrie, J.W. Jr. Williams, and J. Unützer; IMPACT Investigators. 2005. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Medical Care 43(4):381–390.

Asplund, K., Y. Gustafson, C. Jacobsson, G. Bucht, A. Wahlin, J. Peterson, J.O. Blom, and K.A. Angquist. 2000. Geriatric-based versus general wards for older acute medical patients: A randomized comparison of outcomes and use of resources. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48(11):1381–1388.

Barr, V.J., S. Robinson, B. Marin-Link, L. Underhill, A. Dotts, D. Ravensdale, and S. Salivaras. 2003. The expanded Chronic Care Model: An integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the Chronic Care Model. Hospital Quarterly 7(1):73–82.

Battersby, M., P. Harvey, P.D. Mills, E. Kalucy, R.G. Pols, P.A. Frith, P. McDonald, A. Esterman, G. Tsourtos, R. Donato, R. Pearce, and C. McGowan. 2007. SA HealthPlus: A controlled trial of a statewide application of a generic model of chronic illness care. Milbank Quarterly 85(1):37–67.

Beck, A., J. Scott, P. Williams, D. Jackson, G. Gade, and P. Cowan. 1997. A randomized trial of group outpatient visits for chronically ill older HMO members: The Cooperative Health Care Clinic. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45(5):543–549.

Berenson, R., K. Devers, and R. Burton. 2011. Will the Patient-Centered Medical Home Transform the Delivery of Health Care? Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Bernabei, R., F. Landi, G. Gambassi, A. Sgadari, G. Zuccala, V. Mor, L.Z. Rubenstein, and P. Carbonin. 1998. Randomised trial of impact of model of integrated care and case management for older people living in the community. British Medical Journal 316(7141):1348–1351.

Bielaszka-DuVernay, C. 2011. Vermont’s blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost. Health Affairs 30(3):383–386.

Blash, L., S.A. Chapman, and C. Dower. 2010. The Special Care Center: A Joint Venture to Address Chronic Disease. San Francisco, CA: Center for the Health Professions. http://www.futurehealth.ucsf.edu/Content/29/2010-11_The_Special_Care_Center_A_Joint_Venture_to_Address_Chronic_Disease.pdf (accessed August 8, 2011).

Board, N., N. Brennan, and G.A. Caplan. 2000. A randomised controlled trial of the costs of hospital as compared with hospital in the home for acute medical patients. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 24(3):305–311.

Bodenheimer, T. 2011. Lessons from the trenches—a high-functioning primary care clinic. New England Journal of Medicine 365(1):5–8.

Bodenheimer, T., E.H. Wagner, and K. Grumbach. 2002. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: The chronic care model, Part 2. Journal of the American Medical Association 288(15):1909–1914.

Boult, C., L.B. Boult, L. Morishita, B. Dowd, R.L. Kane, and C.F. Urdangarin. 2001. A randomized clinical trial of outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 49(4):351–359.

Boult, C., L. Reider, K. Frey, B. Leff, C.M. Boyd, J.L. Wolff, S. Wegener, J. Marsteller, L. Karm, and D. Scharfstein D. 2008. The early effects of “Guided Care” on the quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journals of Gerontology, Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 63(3):321–327.

Boult, C., A. Frank, L. Boult, J.T. Pacala, C. Snyder, and B. Leff. 2009.Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: evidence for the Institute of Medicine’s “Retooling for an Aging America” report. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57:2328–2337.

Boult, C., L. Reider, B. Leff, K.D. Frick, C.M. Boyd, J.L. Wolff, K. Frey, L. Karm, S.T. Wegener, T. Mroz, and D.O. Scharfstein. 2011. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: Results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine 171(5):460–466.

Boyd, C.M., E. Shadmi, L.J. Conwell, M. Griswold, B. Leff, R. Brager, M. Sylvia, and C. Boult. 2008. A pilot test of the effect of Guided Care on the quality of primary care experiences for multi-morbid older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23(5):536–542.

Boyd, C.M., L. Reider, K. Frey, D. Scharfstein, B. Leff, J. Wolff, C. Groves, L. Karm, S. Wegener, J. Marsteller, and C. Boult. 2010. The effects of Guided Care on the perceived quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: 18-month outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25(3):235–242.

Brenner, J. 2009. Reforming Camden’s Health Care System—One Patient at a Time. Prescriptions for Excellence in Health Care. http://jdc.jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1047&context=pehc (accessed August 11, 2011).

Brodaty, H., A. Green, and A. Koschera. 2003. Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51(5):657–664.

Burns, R., L.O. Nichols, J. Martindale-Adams, and M.J. Graney. 2000. Interdisciplinary geriatric primary care evaluation and management: Two-year outcomes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48(1):8–13.

Callahan, C.M., M.A. Boustani, F.W. Unverzagt, M.G. Austrom, T.M. Damush, A.J. Perkins, B.A. Fultz, S.L. Hui, S.R. Counsell, and H.C. Hendrie. 2006. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer’s disease in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 295(18):2148–2157.

Caplan, G.A., J.A. Ward, N.J. Brennan, J. Coconis, N. Board, and A. Brown. 1999. Hospital in the home: A randomised controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia 170(4):156–160.

Caplan, G.A., A.J. Williams, B. Daly and K. Abraham. 2004. A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department—the DEED II study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52(9):1417–1423.

Caplan, G.A., J. Coconis, and J. Woods. 2005. Effect of hospital in the home treatment on physical and cognitive function: A randomized controlled trial. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 60(8):1035–1038.

Chavannes, N.H., M. Grijsen, M. van den Akker, H. Schepers, M. Nijdam, B. Tiep, and J. Muris. 2009. Integrated disease management improves one-year quality of life in primary care COPD patients: A controlled clinical trial. Primary Care Respiratory Journal 18(3):171–176.

Chodosh, J., S.C. Morton, W. Mojica, M. Maglione, M.J. Suttorp, L. Hilton, S. Rhodes, and P. Shekelle. 2005. Meta-analysis: Chronic disease self-management programs for older adults. Annals of Internal Medicine 143(6):427–438.

Clark, N.M., N.K. Janz, M.H. Becker, M.A. Schork, J. Wheeler, J. Liang, J.A. Dodge, S. Keteyian, K.L. Rhoads, and J.T. Santinga. 1992. Impact of self-management education on the functional health status of older adults with heart disease. Gerontologist 32(4):438–443.

Clark, N.M., N.K. Janz, J.A. Dodge, M.A. Schork, T.E. Fingerlin, J.R. Wheeler, J. Liang, S.J. Keteyian, and J.T. Santinga. 2000. Changes in functional health status of older women with heart disease: Evaluation of a program based on self-regulation. Journals of Gerontology, Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 55(2):S117–S126.

Cohen, H.J., J.R. Feussner, M. Weinberger, M. Carnes, R.C. Hamdy, F. Hsieh, C. Phibbs, D. Courtney, K.W. Lyles, C. May, C. McMurtry, L. Pennypacker, D.M. Smith, N. Ainslie, T. Hornick, K. Brodkin, and P. Lavori. 2002. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. New England Journal of Medicine 346(12):905–912.

Cole, M.G., F.J. Primeau, R.F. Bailey, M.J. Bonnycastle, F. Masciarelli, F. Engelsmann, M.J. Pepin, and D. Ducic. 1994. Systematic intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: A randomized trial. CMAJ 151(7):965–970.

Coleman, E.A., C. Parry, S. Chalmers, and S.J. Min. 2006. The care transitions intervention: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine 166(17):1822–1828.

Community Care of North Carolina. 2010. Treo Solutions Report. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Community Care Networks, Inc. http://www.communitycarenc.org/elements/media/related-downloads/treo-analysis-of-ccnc-performance.pdf (accessed August 11, 2011).

Community Care of North Carolina. 2011. Enhanced Primary Care Case Management System: Legislative Report. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Community Care Networks, Inc. http://www.communitycarenc.org/elements/media/publications/report-to-the-nc-general-assembly-january-2011.pdf (accessed August 11, 2011).

Counsell, S.R., C.M. Holder, L.L. Liebenauer, R.M. Palmer, R.H. Fortinsky, D.M. Kresevic, L.M. Quinn, K.R. Allen, K.E. Covinsky, and C.S. Landefeld. 2000. Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older patients: A randomized controlled trial of Acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48(12):1572–1581.

Counsell, S.R., C.M. Callahan, D.O. Clark, W. Tu, A.B. Buttar, T.E. Stump, and G.D. Ricketts. 2007. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 298(22):2623–2633.

Counsell, S.R., C.M. Callahan, W. Tu, T.E. Stump, and G.W. Arling. 2009. Cost analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders care management intervention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57(8):1420–1426.

CMS (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services). 2009. Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medicare Insurance Trust Funds. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/ReportsTrustFunds/downloads/tr2009.pdf (accessed August 11, 2011).

Crotty, M., J. Halbert, D. Rowett, L. Giles L, R. Birks, H. Williams, and C. Whitehead. 2004. An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: A randomised controlled trial of case conferencing. Age and Ageing 33(6):612–617.

Davis, K., C. Schoen, and K. Stremikis. 2010. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: How the Performance on the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally. New York: The Commonwealth Fund. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications (accessed August 8, 2011).

de la Porte, P.W., D.J. Lok, D.J. van Veldhuisen, J. van Wijngaarden, J.H. Cornel, N.P. Zuithoff, E. Badings, and A.W. Hoes. 2007. Added value of a physician-and-nurse-directed heart failure clinic: Results from the Deventer-Alkmaar heart failure study. Heart 93(7):819–825.

Ducharme, A., O. Doyon, M. White, J.L. Rouleau, and J.M. Brophy. 2005. Impact of care at a multidisciplinary congestive heart failure clinic: A randomized trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal 173(1):40–45.

Elkan, R., D. Kendrick, M. Dewey, M. Hewitt, J. Robinson, M. Blair, D. Williams, and K.

Brummell. 2001. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal 323(7315):719–725.

Epstein, A.M., J.A. Hall, M. Fretwell, M. Feldstein, M.L. DeCiantis, J. Tognetti, C. Cutler, M. Constantine, R. Besdine, and J. Rowe. 1990. Consultative geriatric assessment for ambulatory patients. A randomized trial in a health maintenance organization. Journal of the American Medical Association 263(4):538–544.

Fann, J.R., M.Y. Fan, and J. Unützer. 2009. Improving primary care for older adults with cancer and depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 24(Suppl 2):S417–S424.

Fu, D., H. Fu, P. McGowan, Y.E. Shen, L. Zhu, H. Yang, J. Mao, S. Zhu, Y. Ding, and Z. Wei. 2003. Implementation and quantitative evaluation of chronic disease self-management programme in Shanghai, China: Randomized controlled trial. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81(3):174–182.

Gagnon, A.J., C. Schein, L. McVey, and H. Bergman. 1999. Randomized controlled trial of nurse case management of frail older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47(9):1118–1124.

Gattis, W.A., V. Hasselblad, D.J. Whellan, and C.M. O’Connor. 1999. Reduction in heart failure events by the addition of a clinical pharmacist to the heart failure management team: Results of the Pharmacist in Heart Failure Assessment Recommendation and Monitoring (PHARM) Study. Archives of Internal Medicine 159(16):1939–1945.

Gawande, A. 2011. The hot spotters: Can we lower medical costs by giving the neediest patients better care? The New Yorker January 24.

Gilfillan, R.J., J. Tomcavage, M.B. Rosenthal, D.E. Davis, J. Graham, J.A. Roy, S.B. Pierdon, F.J. Jr., Bloom, T.R. Graf, R. Goldman, K.M. Weikel, B.H. Hamory, R.A. Paulus, and G.D. Jr., Steele 2010. Value and the medical home: Effects of transformed primary care. American Journal of Managed Care 16(8):607–614.

Gill, T.M., D.I. Baker, M. Gottschalk, P.N. Peduzzi, H. Allore, and A. Byers. 2002. A program to prevent functional decline in physically frail, elderly persons who live at home. New England Journal of Medicine 347(14):1068–1074.

Gillespie, U., A. Alassaad, D. Henrohn, H. Garmo, M. Hammarlund-Udenaes, H. Toss, A. Kettis-Lindblad, H. Melhus, and C. Mörlin. 2009. A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in patients 80 years or older: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine 169(9):894–900.

Gitlin, L.N., L. Winter, M.P. Dennis, M. Corcoran, S. Schinfeld, and W.W. Hauck. 2006a. A randomized trial of a multicomponent home intervention to reduce functional difficulties in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 54(5):809–816.

Gitlin, L.N., W.W. Hauck, L. Winter, M.P. Dennis, and R. Schulz. 2006b. Effect of an in-home occupational and physical therapy intervention on reducing mortality in functionally vulnerable older people: Preliminary findings. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 54(6):950–955.

Green, S.R., V. Singh, and W. O’Byrne. 2010. Hope for New Jersey’s city hospitals: The Camden Initiative. Perspectives in Health Information Management (Spring 2010):1–14.

Griffiths, T.L., M.L. Burr, I.A. Campbell, V. Lewis-Jenkins, J. Mullins, K. Shiels, P.J. Turner-Lawlor, N. Payne, R.G. Newcombe, A.A. Ionescu, J. Thomas, and J. Tunbridge. 2000. Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 355(9201):362–368.

Holtz-Eakin, D. 2004. An Analysis of the Literature on Disease Management Programs. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Hughes, S.L., F.M. Weaver, A. Giobbie-Hurder, L. Manheim, W. Henderson, J.D. Kubal, A. Ulasevich, and J. Cummings; Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Home-Based Primary Care. 2000. Effectiveness of team-managed home-based primary care: A randomized multicenter trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 284(22):2877–2885.

Hughes, S.L., R.B. Seymour, R. Campbell, N. Pollak, G. Huber, and L. Sharma. 2004. Impact of the fit and strong intervention on older adults with osteoarthritis. Gerontologist 44(2):217–228.

Huss, A., A.E. Stuck, L.Z. Rubenstein, M. Egger, and K.M. Clough-Gorr. 2008. Multidimensional preventive home visit programs for community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 63(3):298–307.

Inglis, S.C., S. Pearson, S. Treen, T. Gallasch, J.D. Horowitz, and S. Stewart. 2006. Extending the horizon in chronic heart failure: Effects of multidisciplinary, home-based intervention relative to usual care. Circulation 114(23):2466–2473.

Inouye, S.K., S.T. Bogardus, Jr., P.A. Charpentier, L. Leo-Summers, D. Acampora, T.R. Holford, and L.M. Cooney, Jr. 1999. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. New England Journal of Medicine 340(9):669–676.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1978. Aging and Medical Education. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

IOM. 1987. Report of the Institute of Medicine: Academic geriatrics for the year 2000. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 35(8):773–791.

IOM. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2008. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Janz, N.K., N.M. Clark, J.A. Dodge, M.A. Schork, L. Mosca, and T.E. Fingerlin. 1999. The impact of a disease-management program on the symptom experience of older women with heart disease. Women & Health 30(2):1–24.

Jones, J., A. Wilson, H. Parker, A. Wynn, C. Jagger, N. Spiers, and G. Parker. 1999. Economic evaluation of hospital at home versus hospital care: Cost minimisation analysis of data from randomised controlled trial. BMJ 319(7224):1547–1550.

Kalra, L., A. Evans, I. Perez, A. Melbourn, A. Patel, M. Knapp, and N. Donaldson. 2004. Training carers of stroke patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 328(7448):1099. http://www.bmj.com/content/328/7448/1099.abstract (accessed January 6, 2012).

Kane, R.L., and P. Homyak. 2003. Multi State Evaluation of Dual Eligibles Demonstration: Minnesota Senior Health Options Evaluation Focusing on Utilization, Cost, and Quality of Care. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota School of Public Health. http://www.cms.gov/reports/downloads/kane2003_1.pdf (accessed January 6, 2012).

Kane, R.L., J. Garrard, C.L. Skay, D.M. Radosevich, J.L. Buchanan, S.M. McDermott, S.B. Arnold, and L. Kepferle. 1989. Effects of a geriatric nurse practitioner on process and outcome of nursing home care. American Journal of Public Health 79(9):1271–1277.

Kane, R.L., G. Keckhafer, S. Flood, B. Bershadsky, and M.S. Siadaty. 2003. The effect of Evercare on hospital use. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51(10):1427–1434.

Kane, R.L., S. Flood, B. Bershadsky, and G. Keckhafer. 2004a. Effect of an innovative Medicare managed care program on the quality of care for nursing home residents. Gerontologist 44(1):95–103.

Kane, R.L., P. Homyak, B. Bershadsky, S. Flood, and H. Zhang. 2004b. Patterns of utilization for the Minnesota Senior Health Options Program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52(12):2039–2044.

Kane, R.L., P. Homyak, B. Bershadsky, T. Lum, S. Flood, and H. Zhang. 2005. The quality of care under a managed-care program for dual eligibles. Gerontologist 45(4):496–504.

Kane, R.L., P. Homyak, B. Bershadsky, and S. Flood. 2006. Variations on a theme called PACE. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 61(7):689–693.

Kane, R.A., T.Y. Lum, L.J. Cutler, H.B. Degenholtz, and T.C. Yu. 2007. Resident outcomes in small-house nursing homes: A longitudinal evaluation of the initial green house program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 55(6):832–839.

Keeler, E.B., D.A. Robalino, J.C. Frank, S.H. Hirsch, R.C. Maly, and D.B. Reuben. 1999. Cost-effectiveness of outpatient geriatric assessment with an intervention to increase adherence. Medical Care 37(12):1199–1206.

Khunti, K., M. Stone, S. Paul, J. Baines, L. Gisborne, A. Farooqi, X. Luan, and I. Squire. 2007. Disease management programme for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and heart failure in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Heart 93(11):1398–1405.

Landefeld, C.S., R.M. Palmer, D.M. Kresevic, R.H. Fortinsky, and J. Kowal. 1995. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. New England Journal of Medicine 332(20):1338–1344.

Lee, J.K., K.A. Grace, and A.J. Taylor. 2006. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 296(21):2563–2571.

Leff, B., L. Burton, S.L. Mader, B. Naughton, J. Burl, S.K. Inouye, W.B. Greenough, III, S. Guido, C. Langston, K.D. Frick, D. Steinwachs, and J.R. Burton. 2005. Hospital at home: Feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Annals of Internal Medicine 143(11):798–808.

Leff, B., L. Burton, S. Mader, B. Naughton, J. Burl, R. Clark, W.B. Greenough, III, S. Guido, D. Steinwachs, and J.R. Burton. 2006. Satisfaction with hospital at home care. Journal of American Geriatrics Society 54(9):1355–1363.

Leslie, D.L., Y. Zhang, S.T. Bogardus, T.R. Holford, L.S. Leo-Summers, and S.K. Inouye. 2005. Consequences of preventing delirium in hospitalized older adults on nursing home costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53(3):405–409.

Leveille, S.G., E.H. Wagner, C. Davis, L. Grothaus, J. Wallace, M. LoGerfo, and D. Kent. 1998. Preventing disability and managing chronic illness in frail older adults: A randomized trial of a community-based partnership with primary care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 46(10):1191–1198.

López Cabezas, C., C. Falces Salvador, D. Cubí Quadrada, A. Arnau Bartés, M. Ylla Boré, N. Muro Perea, and E. Homs Peipoch. 2006. Randomized clinical trial of a postdischarge pharmaceutical care program vs regular follow-up in patients with heart failure. Farmacia Hospitaliaria 30(6):328–342.

Lorig, K.R., D.S. Sobel, A.L. Stewart, B.W. Brown, Jr., A. Bandura, P. Ritter, V.M. Gonzalez, D.D. Laurent, and H.R. Holman. 1999. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: A randomized trial. Medical Care 37(1):5–14.

Lundström, M., A. Edlund, S. Karlsson, B. Brännström, G. Bucht, and Y. Gustafson. 2005. A multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalization, and mortality in delirious patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53(4):622–628.

Lundström, M., B. Olofsson, M. Stenvall, S. Karlsson, L. Nyberg, U. Englund, B. Borssén, O. Svensson, and Y. Gustafson. 2007. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 19(3):178–186.

Maly, R.C., L.B. Bourque, and R.F. Engelhardt. 1999. A randomized controlled trial of facilitating information giving to patients with chronic medical conditions: Effects on outcomes of care. Journal of Family Practice 48(5):356–363.

Mann, W.C., K.J. Ottenbacher, L. Fraas, M. Tomita, and C.V. Granger. 1999. Effectiveness of assistive technology and environmental interventions in maintaining independence and reducing home care costs for the frail elderly. A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Family Medicine 8(3):210–217.

Marcantonio, E.R., J.M. Flacker, R.J. Wright, and N.M. Resnick. 2001. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 49(5):516–522.

Markle-Reid, M., R. Weir, G. Browne, J. Roberts, A. Gafni, and S. Henderson. 2006. Health promotion for frail older home care clients. Journal of Advanced Nursing 54(3):381–395.

Martin, D.C., M.L. Berger, D.T. Anstatt, J. Wofford, D. Warfel, R.S. Turpin, C.C. Cannuscio, S.M. Teutsch, and B.J. Mansheim. 2004. A randomized controlled open trial of population-based disease and case management in a Medicare Plus Choice health maintenance organization. Preventing Chronic Disease 1(4):A05.

Martin, F., A. Oyewole, and A. Moloney. 1994. A randomized controlled trial of a high support hospital discharge team for elderly people. Age and Ageing 23(3):228–234.

McAlister, F.A., S. Stewart, S. Ferrua, and J.J. McMurray. 2004. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: A systematic review of randomized trials. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 44(4):810–819.

Melin, A.L., and L.O. Bygren. 1992. Efficacy of the rehabilitation of elderly primary health care patients after short-stay hospital treatment. Medical Care 30(11):1004–1015.

Meyer, H. 2011. A new care paradigm slashes hospital use and nursing home stays for the elderly and the physically and mentally disabled. Health Affairs 30(3):408–411.

Milstein, A., and E. Gilbertson. 2009. American medical homes runs: Four real-life examples of primary care practices that show a better way to substantial savings. Health Affairs 28(5):1317–1326.

Milstein, A., and P. Kothari. 2009. Are higher-value care models replicable? Health Affairs Blog. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2009/10/20/are-higher-value-care-models-replicable/ (accessed August 8, 2011).

Mittelman, M.S., W.E. Haley, O.J. Clay, and D.L. Roth. 2006. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology 67(9):1592–1599.