Stimulating Manufacturing in Ohio

Moderator:

Sridhar Kota

Office of Science and Technology Policy

White House

INNOVATION AND U.S.-BASED MANUFACTURING

Sridhar Kota

Office of Science and Technology Policy

White House

Dr. Kota, the moderator for this panel, began with reflections on his own studies of innovation and manufacturing. He proposed a definition of innovation from the National Academies’ Rising Above the Gathering Storm, Revisited report: “Innovation commonly consists of being first to acquire new knowledge through leading edge research, being first to apply that knowledge to create sought-after products and services…, and being first to introduce those products and services into the marketplace….”6 He said that the U.S. does “really well in the first two,” the acquisition and application of knowledge, but has been falling behind over the last 30 years in seizing commercial leadership in new products.

As illustrations of this falling behind, Dr. Kota pointed to many valuable high-technology products already lost to foreign competitors, including “fabless” chips, LCDs, electrophoresis displays for e-readers, lithium-ion and other batteries for cell phones and portable electronics, advanced rechargeable batteries for hybrid vehicles, personal computers, and advanced composites used in sporting goods and other consumer gear. Some of these, he said, can no longer be produced in the U.S. because the supply chains have moved abroad. Many more technologies are at risk, including LEDs for solid-state lighting, next-generation “electronic paper” displays, thin-film solar cells, mobile

![]()

6Members of the 2005 “Rising Above the Gathering Storm” Committee, Rising Above the Gathering Storm, Revisited: Rapidly Approaching Category 5, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2010.

handsets, and carbon composite components for aerospace and wind energy. “I’m not sure we’ll end up capitalizing on our own inventions in those areas,” he said.

The Strong Link Between Innovation and Manufacturing

The reason that technologies can be lost to the nation, Dr. Kota said, is that manufacturing and innovation are strongly linked. The Federal government’s investments are made primarily in basic research, especially through the universities. “We are very good at that, and being the best in the world in scientific discoveries is vital to our success.” However, he continued, “this is no longer sufficient to compete in the global economy. We need to be able to do the rest of it—translating those ideas into prototyping centers, taking them into scaling. We’re pretty good at the first one percent, the inspiration, but it’s that ninety-nine percent, the ‘perspiration,’ where the real challenge is.”

Unless U.S. companies improve at commercializing new technology, Dr. Kota said, they will not be able to innovate the next-generation products. “As you do the scaling, a lot of new product and process innovations come about,” he said. “As an idea moves from a PowerPoint slide into a real product, it must be made safe, cost effective, light-weight, and reliable. If you don’t do that, you will not be able to capture the market.”

A Weakened Industrial Commons

Of central importance, Dr. Kota said, was the collective, overlapping set of competencies and resources known as the “industrial commons” that underlie the development of new technology products. The commons includes engineering R&D, materials, standards, tools, equipment, scalable processes, components, and manufacturing competencies in platform technologies. “Without those commons we cannot innovate,” Dr. Kota said. 7

The U.S. industrial commons has become weak in high-technology sectors, including biotechnology, life science, optoelectronics, information and communications electronics, flexible manufacturing, advanced materials, aerospace, weapons, nuclear technology, and computer software.8 As evidence, he referred to the nation’s expanding trade deficits in advanced technology products. In this category the U.S. maintained a trade surplus until the year 2000, but today suffers a deficit of about $80 billion.

![]()

7Dr. Kota referred to the ideas expressed by Gary P. Pisano and Willy C. Shih in “Restoring American Competitiveness,” Harvard Business Review 87(7-8), July-August 2009.

8National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2008, op. cit.

Innovation and the ‘Missing Middle’

Dr. Kota called innovation the “missing middle” in the process of developing new industries. “You have to put money into knowledge,” he said, “but unless you apply that knowledge, you don’t generate money at the other end. Someone else is then free to take those ideas and capitalize on them. The engineering and manufacturing is what converts that knowledge—something done far more effectively by other countries. For example, he said, Germany spends one-sixth as much as the U.S. in total R&D, but it spends six times as much on industrial production and technology.”

As further illustration he referred to TRLs, or technology readiness levels, that are used to characterize technology development on a scale of 1 to 9. The research supported by the NSF and the NIH, he said, is usually at TRL 1 to 3. “After that,” he said, “when you’ve proved this idea does not violate laws of physics, and it seems to be interesting or potentially useful, you need to build a proof of concept prototype and a simulated environment to advance to TRL 8 or so. Unless you do that the private companies don’t have the confidence to invest.” In the U.S., he said, the Valley of Death exists between TRLs 4 and 7, the realm of engineering and systems work, where both the technology and the manufacturing readiness are tested. Successful models for doing this exist in the German Fraunhofer Institutes and Taiwan’s Industrial Technology Research Institutes. “To transition home-grown discoveries into home-grown products,” he said, “we need ‘Edison Institutes’ modeled after Fraunhofer Institutes for maturing technology and manufacturing readiness.”9

In order to improve this transitional process, Dr. Kota said, we also need a new balance of strategic investments. In the FY2010 budget, approximately $100 billion were designated for R&D all the Federal agencies. Outside the Department of Defense, which focuses on weapons systems, most of this amount supports work below TRL 3. “That is new knowledge for the public good,” he said, “but that’s only the first step. None of the agencies spend enough in the middle, where innovation happens, where an idea is converted into a product.”

“How do we reconcile with investing so much and having little to show?” Dr. Kota continued. “Some might say there’s nothing we can do because there is too much labor competition from China and India.” He echoed Dr. Wessner’s point about Germany and Japan, however, which competed effectively without the advantage of lower wages. In Germany, he said, taxes are somewhat lower, but wages, overhead rates, energy expenses, and the raw cost index are higher. Yet, the bottom line is that Germany has a $200 billion surplus in manufacturing, vs. an $800 billion deficit for the U.S. The comparison with Japan, he said, shows similar results.

![]()

9The Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft undertake applied research of direct utility to private industry. It uses a clustered approach with pilot production centers to close the gap between research and products.

Investing in the Innovation Gap

The challenge for the U.S., Dr. Kota said, is less an issue of how much we invest in R&D, but where we invest it. We should be investing in that innovation gap, he said, and using other tools we already have, such as early procurement, Federal loan guarantees, and scaling through industry cost sharing. “The government can accelerate innovation with a better strategy. And it certainly needs to coordinate Federal investments rather than having every agency following a different direction.”

With regards to strengthening the manufacturing base, Dr. Kota praised public-private partnerships for their ability to catalyze new industries and strengthen existing industries. This could be done in shared facilities, such as technology parks and institutes for technology development, and make better use of the “building blocks” of manufacturing innovation, such as access to capital, tax credits and loan guarantees, a skilled workforce at all levels, and better access to markets. New industries in which the U.S. must be competitive include flexible electronics, nanomanufacturing, advanced vehicle technologies, and robotics. Complex and costly skills that are required in these industries will require both government and industry forces, especially modeling and simulation and IT-enabled manufacturing. These will require more coordinated actions across agencies and industries if they are to play a fundamental role in revitalizing American manufacturing. “Industry and the Federal government must come together,” he said, “to co-invest in technologies.”

Dr. Kota closed by emphasizing several steps that the Federal government is taking to enable manufacturing in the states and regions. One is NSF support for proof of concept centers in universities—“a small step, but in the right direction.” Another is the emphasis on advanced manufacturing featured in the FY12 budget, including a new initiative by the Economic Development Administration to help small businesses gain access to modeling and simulation tools. These are currently too expensive for most new firms, even though they are known to reduce costs, improve quality, and cut time to market. This initiative, called the Midwest Pilot, offers modeling and simulation access in the form of software services to lower the barriers to entry and allow “small manufacturers to move up the food chain in terms of innovation and improvements in design and quality.” Other examples of Federal-local initiatives, small process manufacturing, robotics, flexible electronics, and other technologies, to allow small companies to gain the skills they need to compete globally.

THE STATE MANUFACTURING CHALLENGE

Eric Burkland

Ohio Manufacturing Association

Mr. Burkland said he would offer information and data that show why Ohioans are optimistic about the future of manufacturing in the state and how it can be a platform for innovation. Manufacturing generates about 18 percent of the gross state product, about twice that of any other private-sector activity (next in rank is real estate, rental, and leasing, at 10 percent.). Manufacturing output in 2008 was $84 billion, which was $37 billion higher than the next nongovernment sector. The sector employs about 600,000 people, or 14 percent of the work force. The largest employer in the state is government. In terms of payroll, however, manufacturing still leads, with about $38 billion in 2008, followed by government, health care, social assistance, and retail trade. Ohio is the seventh largest exporting state, selling about $34 billion worth of goods in 213 countries and territories. The state ranks first, second, or third among U.S. manufacturers in 84 different categories of manufacturing, as specified by the North American Industry Classification System.10

The level of leadership in manufacturing, Mr. Burkland said, was largely a function of government policies and practices. These include:

- Labor: government is largely responsible for educating a skilled workforce.

- Technology and business practices: Government has significant inputs, including support for research, protection of intellectual property, and creation of an environment that facilitates technology commercialization.

- Equipment: Availability of capital is influenced by how government regulates the flow of credit. Capital availability for this has been “pretty much a crisis” for the last couple of years, though it is starting to ease.

- Location: Governments establish zoning, regulatory, and environmental rules and provide incentives.

- Transportation: Most of the infrastructure is publicly held and all of it publicly regulated.

- Energy: Government drives prices by numerous policies.

- Environmental regulations: Government drives costs through emission and control laws.

![]()

10For example, Ohio ranks #1 in wood products, adhesives, plastic bottles, refractory goods, rolling and drawing steel, nonaluminum foundries, paint and coatings, resins, rubber products, pressed and blown glass, ferrous metal foundries, custom roll forming, hand tools and saw blades, bearings, plastic and rubber machinery, rolling mill machinery, wood kitchen cabinets, heat treating, ordinance, machine tools, heavy duty trucks, and brooms, brushes and mops.

- Access to markets: Government facilitates access, promotes exports, and prevents unfair imports.

- Taxation: A major cost driver. “We do not have a tax structure that’s favorable to manufacturing.”

Mr. Burkland offered a preview of the Ohio Manufacturing Network of Innovation, which was about to be launched. It is an on-line technology platform to support open innovation, and to connect Ohio manufacturers with researchers in universities, Federal labs, and economic organizations. “The supply chains here have been pretty rigid for many years,” he said, “and all this pain has caused us to reach outside of ourselves. So we now have a lot more networked capacity than we used to.”

An Open Innovation Approach

This includes, for example, companies in the auto supply chain that are now connected to the appliance supply chain and the aerospace supply chain. It allows companies to showcase their areas of expertise and interest, especially in design, materials, and process technologies, and to quickly identify and contact “best-in-class” technical experts relevant to needs. The network was patterned somewhat after Proctor and Gamble’s open innovation approach, allowing a researcher at Timken, for example, to discover that someone at the University of Dayton has already solved a particular problem. “We’re trying to see through this opaqueness between institutions to discover if we can create a culture for cooperation,” he said. One of the two Manufacturing Extension Partners, administered by NIST, has taken a lead in developing the technology, along with P&G, GE, and NorTech. “What we need is not new organizations,” he concluded, “but better connectivity and productivity out of what we have.” In conclusion, Mr. Burkland said that the Ohio Manufacturing Network would have pleased Col. John G. Battelle, the Ohio industrialist whose fortune formed the basis for today’s Battelle Institute, the world’s largest independent R&D organization. Battelle saw the advantages of networking a century ago when he sent a letter to 20 other leading industrialists. “His message was: ‘Let’s find a better way to work together.’ Now there was an innovator.”

STIMULATING MANUFACTURING IN OHIO: AN INDUSTRY PERSPECTIVE

Mr. Griffith began by saying he represented two enterprises at the symposium: Timken, a $4+ billion manufacturing firm of which he is CEO, and Magnet, the Manufacturing Advocacy and Growth Network, which he also chairs. Magnet is a not-for-profit economic development enterprise in northeast

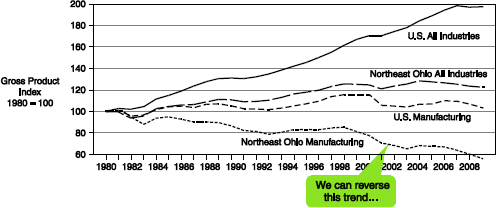

SOURCE: Cleveland State University Levin College of Urban Affairs update of data contained in <http://urban.csuohio.edu/economicdevelopment/reports/EconomicBrief_2010_Final.pdf>.

FIGURE 2 Northeast Ohio faces a severe economic challenge.

SOURCE: James W. Griffith, Presentation at the April 25-26, 2011, National Academies Symposium on “Building the Ohio Innovation Economy.”

Ohio with a mission “to support, educate, and champion manufacturing with the goal of transforming the region’s economy into a powerful, global player.”

He said that he became involved in economic development in northeast Ohio “because we were going through a transformation at Timken” which applied directly to issues experienced by other manufacturers. He displayed a graph, generated by NorTech, that showed Ohio falling steadily from a leadership position in 1980 to its present position far behind the rest of the nation, both in manufacturing and in all industrial growth. “I am a believer that we can change this,” he said. “We’ve done it at Timken, and I believe we have learned some lessons that apply broadly.”

Like Ohio, Mr. Griffith said, Timken has a strong heritage of success. From 1960 to 1980, the firm performed strongly, with returns on invested capital above 20 percent year after year. “A bad year was just 20 percent,” he said. “And this kind of world-leading success was typical of northeast Ohio then.” In the 1980s profits shrank into losses, and for the next 20 years the company struggled to right itself. “I’ve been there for 26 years and I never knew that good time,” said Mr. Griffith. “I’ve been there for the struggling time.”

10 Years of a ‘Grow and Optimize’ Strategy

In the late 1990s the company changed its strategy and profits began to return, and after 2009 they reached record levels. “How we did this is not a secret,” Mr. Griffith said, “and it didn’t happen overnight. It is the result of a 10-year application of a highly focused strategy.” This strategy, which he called “grow and optimize,” began with innovation, he said: understanding where the company differentiates itself from others, and which markets to target. “We

were a bearing company when we started. We’re still mostly a bearing and steel company. But we’ve learned to take the technology and apply it to markets where we could differentiate and expand. We started as primarily an automotive manufacturer; today we’re an aerospace manufacturer, and infrastructure manufacturer. We have a very aggressive growth business in Asia. We’re a steel company. We melt a million and half tons of scrap a year and turn it into super high alloy for new markets. The management team of our steel business gets paid an incentive on new product generation. Last year they earned a nice bonus because 35 percent of what they sold was a product in new markets. $35 million of that was exported to China. So when you’re selling China steel that is made in Ohio, you’re doing something radically different.” This part of the strategy, he said, was fundamental. Timken had to be the world’s best manufacturer, he said, so the company invested heavily in growing, building its skills, and spent a quarter of billion dollars redoing the company’s systems infrastructure.

That part of the strategy, Mr. Griffith said, was “fun”—but another part was not. “We looked at our business and saw there was a big chunk of it we couldn’t afford to fix. And the company couldn’t survive if we didn’t deal with it. The company invested a quarter of a billion dollars in China, and now exports as much to China as it makes in China. But to be in that market we had to be a very different company. We had to divest $1.5 billion worth of businesses that we couldn’t win in, and we closed 30 manufacturing sites in northeast Ohio. That’s the hard side to innovation.”

This “grow and optimize” model worked. “By the time our strategy was noticed, we were an instant success on Wall Street,” he said. “Our stock price popped 100 percent. We were one of the top industrial stocks last year. But we were not an overnight success. This came after 10 years of hard work, innovating, ripping out the infrastructure that inhibited innovation within a 100-year-old company.”

A Heritage that Threatens Development

Mr. Griffith continued that the same principles apply to much of northeast Ohio. The region has a strong heritage of manufacturing. It was a pioneer in the aerospace industry; it built up the auto industry, which brought Timken to the region originally; it was a leader in the national steel industry. “Unfortunately, that heritage created an infrastructure that threatened to strangle the kind of economic development we need—the sense of innovation.”

In addition, the state is heavily taxed. A study by the Tax Foundation ranked Ohio 46th in its business tax environment. “There are three major corporations that wouldn’t be here if the state government hadn’t taken specific action to address their circumstances in the last year,” he said. “This is an infrastructure issue we have to deal with.” Another is the presence of more than 2,300 governmental entities in the state, which are costly to maintain and have overlapping functions. “Someone has to pay for those entities,” he said. Because governments have proliferated to this extent, he said, it is “confusing to do

business here. We’ve done a lot in Columbus, and a lot in Cuyahoga County, but there’s a lot more to do. We’re inventing new kinds of government. We’ve simply got to continue to drive at that.”

Mr. Griffith also said that Ohio is not competitive when it comes to “union participation,” being in the top quartile in union membership. “That’s a heritage of being a large industrial manufacturing economy,” he said, “along with a legal system that reinforces it.” He said that a pending senate bill would address some of those issues, but that the issue was complex and difficult to change. “When you look at those two heritages,” he said, “the implication is, many large manufacturers who are looking to invest somewhere see this infrastructure and we don’t even make the short list. We have to have the fundamentals that make us a competitive state for investment.”

Strengths in SMEs and Education

Turning to “the positives,” Mr. Griffith said, the region’s heritage had left it with two pillars of strength. The first is small and medium-sized businesses. The 16 counties of northeast Ohio have some 8,000 SMEs, which provide a broad foundation on which to build. “Unfortunately,” he said, “many of them were founded as outsource suppliers to big companies like Timken, and they have to acquire the skills to innovate and better access to high technology.”

A second pillar, Mr. Griffith said, is great strength in higher education, including a network of 23 colleges and universities enrolling 160,000 students. “The challenge for us is to leverage those students into an innovation economy.” Part of the mission of MAGNET, he said, along with NorTech, is to better link manufacturers and universities, so that students acquire the skills needed by the manufacturers.” That’s exactly what happened at Timken,” he said. “We were manufacturers, but we had to learn the skills of reaching out and investing in R&D in the regional universities.” A new initiative to encourage this is the Partnership for Regional Innovation Services to Manufacturers (PRISM), which is funded jointly by the Fund for Our Economic Future, the Cleveland Foundation, and the Brookings Institution. The program will reach out to small businesses to teach them skills, build networks, and begin an “embryonic phase of growth within existing businesses.”

In closing, Mr. Griffith urged his fellow Ohioans to “keep it simple.” He said that Ohio already has a strong network of enterprises focused on innovation, which would be described during the symposium. “There is no need for new organizations, but for better use of existing ones. They’re focused on entrepreneurship, on intrapreneurship—internal innovation—and on changing the infrastructure. We have an incredible wealth of assets. We simply have to fix the infrastructure underneath them that is a heritage of our historic success, drive the success of our universities, and bridge it across the small enterprises. Then we can leverage those enterprises to create the innovation economy we need.”

REVIVING MANUFACTURING: THE ROLE OF NIST

Phillip Singerman

National Institute of Standards and Technology

Dr. Singerman, who arrived at NIST only three months previously after some three decades in technology-based economic development, professed a long-standing personal connection to the region. A graduate of Oberlin College, he has worked with institutions in the region on Federal engagement strategies, including NorTech, Jumpstart, BioEenterprise, the Fund for Our Economic Future, and MAGNET. “Today,” he said, “I’m delighted to represent NIST, whose Technology Innovation Program is one of the three Federal co-sponsors of this event.”

He began by “reintroducing” his audience to NIST, and some of its activities in Ohio. NIST was founded in 1901, contemporaneously with many corporate laboratories, including Bell Labs, AT&T, and General Electric. It was “one of Ohio’s presidents,” he said, William McKinley, who recognized that the U.S. needed a sophisticated national system of industrial standards and measurements to compete with the more developed industries of Europe.

Working Directly in Support of Industry

NIST has the unique Federal mission of working directly in support of industry as a non-regulatory agency. Its role has deepened in response to changing requirements of industrial development. Dr. Singerman quoted NIST director Pat Gallagher, the first Undersecretary of Standards for Technology: NIST has become “industry’s national laboratory. With the decline of the corporate laboratories created over a century ago,” he said, “NIST now performs many of those functions.”

Last year NIST reorganized, combining 12 academically oriented laboratories into six mission-driven operating units: national user facilities, the center for nanoscale science, the center for neutron research, technology laboratories in engineering and information, and measurement sciences. NIST also combined the external partnership programs into one directorate which Dr. Singerman was selected in 2011 to head. This reorganization was driven by NIST’s central role as an innovation agency, especially for manufacturing. Also driving the reorganization was the projected doubling of the R&D budget in the physical sciences and the rebalancing of R&D investments among the NSF, the DoE’s Office of Science, and NIST. This reorganization was proposed in the 2007 America COMPETES legislation, and reaffirmed in the 2010 reauthorization of the America COMPETES Act.

Dr. Singerman offered specific examples of how NIST attempts to strengthen innovation. The first is the Manufacturing Extension Program (MEP), an external partnership in which James Griffith of Timken and others in Ohio have been “consistently involved.” He said that the MEP is “the closest we have

to the Fraunhofer network, but it is really ‘Fraunhofer lite.’” The MEP is a national program with about $125 million in annual funding, with two-thirds matching by the states and private sector. “This is a sustainable model that has endured for over a quarter of a century,” he said. “The MEP is the gold standard for effective national networks of technology dissemination and adoption to drive economic growth.”

Dr. Singerman said that through the MEP, NIST has made major contribution to the Ohio economy over the last several years. From fiscal years 2006 to 2012, NIST funding of $27 million has been matched by over $70 million in cost sharing from the state and partner organizations, and has led to significant increases in sales, new investments, and jobs. While the MEP is best known for promoting lean manufacturing and cost savings, it is now developing national network programs to promote new products and innovation services, in partnership with regional organizations. Last fall the MEP awarded $9.1 million to 22 projects, including two in Ohio, one of them to MAGNET.

The second example was the TIP program, which, Dr. Singerman said, resembles the SBIR awards “on steroids.” That is, the TIP grants, at $3 to 5 million, are larger, but still aimed primarily at small, technology-based companies. TIP succeeds the Advanced Technology Program, which for 15 years provided competitively awarded funding matched by the private sector for technology research and development. Over a third of all ATP awards supported manufacturing technologies. Ohio received 26 ATP awards across all categories totaling nearly $90 million. The TIP program supports precompetitive technologies of small and mid-sized companies, with an increasing focus on manufacturing technology. In the past two years, 21 awards have been made to manufacturing firms, representing over $60 million in Federal funds.

‘Enormous Interest’ in Innovative Manufacturing

Dr. Singerman noted an “enormous capability and interest” in industry in innovative manufacturing. The most recent TIP solicitation for manufacturing technology drew 110 proposals, of which only nine could be funded. Some 85 percent of those recipients had fewer than 35 employees and were less than 10 years old; two-thirds were less than five years old, with 15 or fewer employees. “So this program really targets the small, high-growth companies that are the key to our economic success,” he said.

Ohio has been active in the both ATP and TIP programs, with 10 percent of all TIP awards and 14 percent of all TIP manufacturing awards going to Ohio companies. Companies receiving awards are MesoCoat, Angstrom Materials, Hypertech Research, and Kent Displays. NorTech helped position Kent Displays to successfully compete for the TIP award, with MAGNET and the University of Akron as participants. He called this an illustration of the power of connectivity.

Dr. Singerman closed by mentioning several other NIST programs:

- NIST has managed the Malcolm Baldwin National Quality Award for 25 years. Again, he said, Ohio has been active in this program. Of a total of 87 winners of the Baldridge Award since 1988, four are based in Ohio.

- NIST’s Technology Partnerships Office builds and sustains technology partnering activities between NIST laboratories and industries. This includes “an active and specialized technology transfer SBIR program.” Since 2005, the office has issued three patent licenses to Ohio firms, five SBIR awards, and 12 cooperative research and development agreements (CRADAs).

- The Israel-U.S. Binational Industrial Research and Development (BIRD) foundation has for more than 30 years lent support to companies working jointly in the two countries. Its mission is to “stimulate, promote, and support industrial R&D of mutual benefit to the U.S. and Israel.”

- A new program in the planning stage for 2012 is an Advanced Manufacturing Technology Consortium. Based partially on the Sematech model, its goal is to support creation of industry-led research and development consortia. He closed by inviting ideas from the audience: “We will be reaching out to the community for your ideas on how to structure this.”

DISCUSSION

A questioner noted that he had not heard any comment about the new manufacturing technology known by a variety of names, such as rapid prototyping, custom production of parts, or additive manufacturing, and asked if it was more than a curiosity. Dr. Kota said that it is “very much more than a curiosity,” and that he had begun experimenting with such techniques more than 12 years ago in studio lithography. He said that rapid prototyping has brought many changes, such as shortening the product development cycle and enhancing the ability to see from packaging considerations how a product fits. “These techniques are still not ready for mass manufacturing,” he said, “but they will bring great advances in making one-off parts and custom-designed parts.”

High-tech Behavior by Traditional Business

Mr. Griffith said he used this high-technology process at Timken, and that even though some people do not see the manufacture of specialty steel, bearings, and even helicopter transmissions as “high-tech,” a goal is to transform traditional businesses by using just such new technologies. “It does change the way you think about product proliferation and the ability to enter new markets, and differentiate yourself in the marketplace. Let me tell you, “Timken is a very high-tech company,” even though it is not part of the new

categories that occur to many people, such as biotechnology or nanotechnology. The questioner noted that the polymer industry offers a “big opportunity for this technology to produce a broader array of parts and get into smaller scale manufacturing, rather than simply one-off projects. Mr. Griffith added that his company had “a great cooperative program at the University of Akron to advance our polymer products” that lowers cost and raises competitiveness.

Mr. Baeslack added that Ohio is “brilliant at materials, and there are a lot of applications in new tooling. Figuring out a faster, cheaper, more flexible tooling set opens up all kinds of new product development opportunities.”

Dr. Wessner posed two questions: (1) What could we do from the Federal or state levels to provide greater support for public-private partnerships, which are “the type of thing that our German colleagues excel at;” and (2) how significant is the 13.6 percent rate of unionization in Ohio, which only modestly exceeds the 11.6 percent national average for states? He added that Germany is “heavily unionized,” with union members on corporate boards, and yet it is successful at manufacturing and exporting.

Mr. Griffith, in response to the query about how Washington can help, praised the Partnership for Regional Innovation Services to Manufacturers (PRISM) initiative being developed by NorTech and MAGNET as an “interesting opportunity. “One-half of it helps educate people like me on how to work on partnerships,” he said. “The other half makes sure places like Akron and Case have robust R&D capabilities. Both have to happen; then you have to leave those of us at the state level to make it work.”

With regard to unions, Mr. Griffith said that the state’s legal infrastructure does reinforce unionization, as do the traditional mindsets. One challenge for Ohio is that the compensation paid by older unionized industries is in the range of $60,000 to $80,000 to workers who tend to have only high school training but who have acquired seniority in their jobs. These positions were now in decline “because in a competitive market there are people who will do the same job for lower cost. When people who want to invest in manufacturing see our environment, and compare it with South Carolina where wages are half as much and state laws are supportive of people working for a company vs. having a third party represent them, they choose to invest there. That is a fact of economic development in building new factories.”

Dr. Proenza asked about some confusion surrounding the manufacturing industry. “Many believe it is dying, but much of the data seems to show it is growing in value, but growing by productivity and automation.” Mr. Baeslack agreed with the second premise, adding that that “the biggest problem in manufacturing is misunderstanding its foundation. Each presidential election year we get calls from outside newspapers wanting to take pictures of boarded up steel mills. That’s not Ohio today. Ohio today is a remarkable productivity engine in manufacturing, and most of the job losses have come because of new technologies and new management.”

The Role of Venture Capital

A questioner turned to the topic of funding for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). “The equity and venture capital groups really do not seem interested in providing funding to small companies because they do not make enough money.” She asked whether VC companies were “getting back into the game.” Dr. Kota replied that smaller companies bring with them a higher level of technological risk, and to address their needs “you need to do more than SBIR bridge funding to mature the technology” until it is proven and ready VC firms. This, he said, is an opportunity for Federal and state entities to work together with companies.

The questioner asked if venture capital firms are too risk averse. Mr. Pogue said that “as a venture capitalist, it is not a question of being risk averse; we live with risk all the time, including the risks of very early-stage startup companies.” He went on to say that of about 700,000 new companies started every year, VC firms invest in only about 1,000 of them, or 1 in 700. They lose all of their investment in about 30 percent of companies they invest in, and earn just marginal gains in another 30 percent. “A major concern,” he said, is that most of the small companies seeking capital do not have business plans that are ambitious or believable enough to make the kinds of returns that the pension funds and endowments who supply capital to VCs require. We venture capitalists have to do better than the stock market over a period of time if we are to sustain funding and not be shut off from the pension funds. We find that in most cases, small firms looking for support are not really interested in high growth, in diluting ownership, or becoming public companies. They are interested in cheap capital.”

The questioner proposed further that one responsibility for venture capital companies is to help small firms create jobs. Mr. Griffith agreed with the urgent need for job creation, but that this had to be built on a strong business foundation. “The investments of VC firms aren’t aimed at creating jobs, they’re aimed at getting a return,” he continued. “It’s the same for Timken. We’re not about employing people, we’re about getting an economic return, and that’s the only way we get the right to employ people. Our objective is to build an economy, and if you build an economy, the jobs will come.”