Innovation Clusters and Economic Development

Moderator:

Lester Lefton

Kent State University

Dr. Lefton, the moderator, set the tone for a panel on clusters by using a mathematical analogy. “In the case of economic development,” he said, “we talk about putting groups of things together in a situation where we hope 2 + 2 + 2 will equal 14, or, in the case of Ohio, maybe even 27. That’s our focus: how to leverage existing resources by combining similar industries where people are doing similar kinds of work. Our panel is going to focus on how we can create policy changes, an economic climate, and a set of cooperative ventures that will provide the platform needed to generate great leverage.”

CLUSTERS AND THE NEXT OHIO ECONOMY: WHAT IS NEEDED

Lavea Brachman

Greater Ohio Policy Center

Ms. Brachman, executive director of the Greater Ohio Policy Center, whose office is located in Columbus, said that she is also a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, where she has worked to identify a structure for policy reforms in Ohio. She said that this has necessarily meant working in partnership with not only the state government, but also with local governments, metro areas, and regions. “While state participation is necessary for economic development,” she said, “it’s not sufficient.”

Ms. Brachman said that if regional economies and “metros” are the economic drivers of the 21st century, and if cluster development is a promising strategy, and if anchor institutions are important sources for growing clusters, then Ohio should be well positioned. However, she averred that the picture is more mixed, especially as applied to transitional economies. I believe we will prevail, but today I want to explore the premises, and some barriers.”

Putting a “cluster growth” policy into action, she said, begins with a place-based approach, aligning multiple players with “intense knowledge about

the sectors.” The application of a cluster strategy in the context of transitional economies must be paired with a broader economic restructuring.

The Greater Ohio Policy Center, Ms. Brachman said, thought of itself as the “smart growth” organization, with a mission of “promoting public policy to grow Ohio’s economy and improve the quality of life through intelligent land use.”

Initially, Ms. Brachman said, the group began with a study of sprawl and urban core revitalization. But when it joined with Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, it saw that land use challenges could only be addressed after examining the local economies and determine why they were not growing. Last February it issued a report, “Restoring Prosperity,” with 39 policy recommendations, beginning with “Ohio can compete in the next economy.”11 The report concluded that “metro areas and regions will drive that economy,” but that substantial improvements in governance must be made if positive changes are to be affected.

Ms. Brachman offered the working definition of clusters as “geographic concentrations of interconnected firms and supporting or coordinated organizations.” She said that a cluster could be an effective tool to jumpstart the economy, “but it’s not a panacea. Emerging clusters should be supported only when they can be justified by data.”

Among the general challenges she saw were that “transferring knowledge is a complicated process,” as is knowing where to intervene and when to bring products to market. It is difficult to find a fit between university research strengths and local economic structures, a problem that “can’t be solved entirely by a cluster approach.” Finally, it is difficult to generate win-win strategies that can both benefit institutions and transform the community.

A Challenging Business Climate

Certain features of Ohio, Ms. Brachman said, made for a challenging business climate. First, the extent of economic decline, she said, was “unparalleled.” There is also an unusual diversity of regional economies. The seven or so major metropolitan areas were all grounded in specific, mostly different industries: Dayton specialized in autos, Toledo in glass, Youngstown in rubber, and so on. “We’re sort of stuck with older economies that still exist. With the layering on top of those older industries, it is harder to identify the key growing clusters.” It is also a challenge to connect regional economic growth and the power of the metros with neighborhood revitalization. The cities have emptied out, leaving high concentrations of poverty. For example the population of Cleveland dropped from 900,000 to 400,000 between 1950 and 2010, the population of Cincinnati from 500,000 to 300,000. A disconnect persists between skill level and job creation, and a fragmentation of government reduces

![]()

11Jennifer Vey et al., “Restoring Prosperity: Greater Ohio and the Brookings Institution,” Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 2010.

the possibilities for collaboration. “That makes it difficult to use clusters as the panacea,” she said.

Ms. Brachman also agreed with Mr. Timken that Ohio is a state with antiquated governance systems and high costs. “These detract from the innovation focus we need, from business development, and tends to promote interlocal competition and ‘poaching’ that undercuts regional competitive capacity.” She said that 86 percent of states have fewer governments per 100 square miles than Ohio.

The state suffers from a confusing combination of historic factors and modern sprawl. In the early agricultural economy, county lines were drawn so that one could travel to the county seat and home again in a horse and buggy from anywhere in the county in one day. Agrarian economies were more localized, and not easily compatible with today’s global economy based in metro regions. Land consumption, or sprawl, has outpaced population growth, and sprawl without population growth results in more local government.

At the same time, Ms. Brachman added, there are opportunities. For example, the state’s economic history is defined by pockets of concentrated industrial activity rooted in the major cities. Because there are seven or eight of those, they present an opportunity exceeding other states, most of which (Illinois, Indiana) have only one major city. “Theoretically,” she said, “if the metro and regional economies are our drivers, we have many of those. We just have to figure out how to leverage them and return ourselves to a basis where each of these cities can thrive uniquely. We can also make good use of multiple anchor institutions rooted by place, such as the University of Cincinnati, the Uptown Consortium, and University Circle in Cleveland.

The Need for Governance Reform

In planning next steps, Ms. Brachman said, the state needs to be “very intentional,” beginning by encouraging natural clusters, but also by removing obstacles, especially through governance reform. “Otherwise these will continue to undercut our competitiveness and prosperity,” she said. “The role of governance should be to facilitate, not hinder, cluster growth.”

Ms. Brachman listed several suggested ways to bring about local governance reform. First, creation of a Governance Reform Commission, which would collect data and monitor the growth and needs of those governments. Second, she suggested the creation of a framework for pooling resources regionally, a form of revenue sharing in which “the state needs to be playing a much bigger role. We also need to make mergers, consolidation, shared services, and alternative governance structures more ‘permissive.’” In many cases, she said, even if mergers of small government entities were shown to be desirable, as between a city and county. They are not permitted under state law. Finally, she suggested that more data needs to be collected on local government costs. All of these steps, she said, must be taken “in the service of creating a more

innovative environment and reducing the costs that undercut our competitiveness.”

Governments also have a larger role to play in creating a fertile environment for clusters. This process can begin with public-private partnerships. Here the private sector needs to lead the way, but public intervention by government needs to create the right conditions to encourage cluster growth.

Doing this, Ms. Brachman said, requires a “multilayered” approach, with public policy restructuring at local, state, and Federal levels, as well as better and more agile partnerships across organizations and across government, business, and nonprofit sectors. She offered Pittsburgh as a nearby example, in its ability to bridge some gaps by creating a regional organization that is “not too large to function.”

Another way to promote cluster development is to create a culture of innovation. Key components of such a culture are that it led by the private sector and promotes a productive blend of competition and cooperation; this would more closely resemble the collaboration commonly seen in Silicon Valley than the more hierarchical and secretive behaviors of Route 128 near Boston. This culture must also remove obstacles and inefficiencies, and encourage public investments in education and training. Create a culture of innovation is a major challenge. It may begin with anchor institutions that try hard to leverage their research capacity. Questions remain about the best ways to generate commercialize new products.

The Role of Anchor Institutions

The role of anchors, such as universities, in generating new knowledge is critical in advancing innovation, but universities cannot do this alone. They have their own challenges, such as decentralization. Also, anchor institutions may be beneficial at a broad macro level, but many moving parts must be addressed at local and regional levels, such as knowledge transfer, community revitalization, and education and training. An emphasis on anchors is consistent with putting knowledge first, she said, instead of incentive and financial packages.

When considering the role of anchors in weak market economies, Ms. Brachman said, community transformation cannot be overlooked while generating cluster growth. Community transformation is pivotal to economic transformation—a realization that Akron, Cincinnati, and other cities have faced fully. The efforts of employers, purchasers, developers, educators, and neighborhood groups must be fully engaged and coordinated. As an example, she pointed to the home ownership incentive program of Ohio State University and forgivable loans for the neighborhood by the University of Akron and Case Western Reserve.

Ohio, Ms. Brachman continued, is uniquely positioned with multiple anchor institutions that are rooted by place. These have the potential to bring

growing positive impact to local economies. This impact can be increased by linking the anchors with clusters and business growth. As examples she listed the University of Toledo, University of Akron, University of Cincinnati, OSU, Case Western Reserve, Wright State, Youngstown State, and Ohio University.

Ms. Brachman said that a recognition that Ohio needs to take a different approach to economic growth dated roughly from 2005, when a report by Deloitte was published.12 This report identified several clusters, and while they were not truly place-based, the ensuing discussion “certainly moved the concept along.” The report not only identified areas of economic strength, such as motor vehicles, polymers, and clinical medicine, but also institutions with crucial roles, such as the Ohio Third Frontier and the Hubs of innovation. While the seven Hubs, she said, were products of the previous state administration, their objective of encouraging regional growth by connecting anchors with downtowns and with promising business clusters was a step “in the right direction.”

“This kind of economic restructuring and cluster development does not happen on its own,” Ms. Brachman concluded, “and you need to be thinking how to organize it for success. It seems to us need that we need to leverage the best of democracy, and do it both from the top down and the bottom up. Finally, I’d like to assert that regions are laboratories of democracy, and that they are best approached by a placed-based strategy. It doesn’t work to just spread resources around like peanut butter.”

INFRASTRUCTURE FOR THE 21ST CENTURY: HOW EDA MIGHT HELP

John Fernandez

Economic Development Administration

Mr. Fernandez began by saying he is a native of Ohio, and a former mayor of Bloomington, Indiana, who understands the challenges of the Midwestern states and regions from personal experience. He said that President Obama understands them as well, and is “very committed to the notion of winning the future by out-innovating, out-educating, and out-building” the competition. He added that “in my world, the concept of investing in our future is not at odds with the notion of a sound fiscal policy. It requires tough choices, it requires prioritization of investments. That’s certainly what all of us have been charged to do within our own agencies.”

Mr. Fernandez said that for the EDA, which sits within the Department of Commerce, this charge means “taking hard looks at things that have been around forever, and may not perform as well as they used to.” The better course, he said, was “a government that’s actually organized around performance and around the challenges of the 21st-century economy.”

![]()

12Deloitte.

Mr. Fernandez defined EDA’s role as providing “the ground troops that try to build up these regional environments.” He said that since its founding in the 1960s, the EDA had evolved considerably from an economic development organization focused primarily on basic infrastructure to one that is focused on how to build an innovation economy. “We talk almost every day about how you have to have competitive regions if you’re going to have a strong national innovation agenda. And we have to focus what we do in my agency on the regions, and on innovation ecosystem development.”

The Power of Regional Collaboration

Mr. Fernandez said that he had been working in economic development for about 20 years, and that during his time as mayor of Bloomington IN, “I was involved in the 20th-century economic development game as fully as anybody.” The shortcoming of the old model, he said, was that it treated economic development as a zero-sum process. Rather than focusing on the competition in China or Brazil or other places around the world, “we were competing with Ohio or Indiana or just down the highway within Indiana. That focus on interstate squabbles is really dated.”

If the U.S. is going to win the future, he said, it has to collaborate regionally. Normally this is done well in the Midwest, he said, but there are “lapses.” Members of the Great Lakes Commission, he noted, generally collaborate and pool resources for the benefit of the region. But when fiscal pressures build, the states may decide to raise taxes a little and suddenly “the surrounding governors pounce on them and try to steal their businesses because they now have lower taxes. I think that’s the wrong model. Our country won’t out-innovate in the long term if we just try to steal from our neighbors.”

From ‘Grant Mill’ to ‘Network Broker’

The way to win the future, he said, is to build an “ecosystem” where organic companies are born, where new companies thrive, and where long-term investment can create jobs locally and regionally. EDA is focused on collaboration models, which means “doing economic development differently. I tell everyone that we’re trying to move away from being a ‘grant mill’ to being a ‘network broker,’ where our work is to connect people, line up resources, and be a catalyst in the investments we make.”

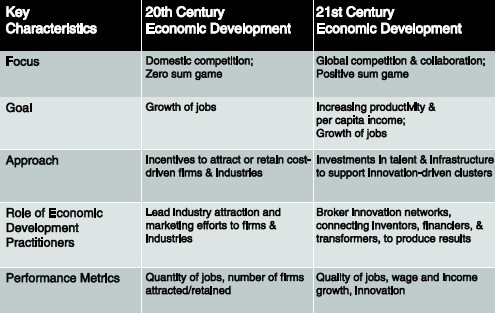

FIGURE 3 A new economic development model.

SOURCE: John Fernandez, Presentation at the April 25-26, 2011, National Academies Symposium on “Building the Ohio Innovation Economy.”

If the EDA can leverage economic assets on a regional basis, Mr. Fernandez said, they can help sustain growth. “I don’t think you can be just about low cost; that only gets you so far. It’s got to be about high talent, innovation, leverage, and public-private partnerships. Those are the resources our agency and this administration tries to seed and encourage.” The agency’s “leverage points” for sustainable and inclusive prosperity are to (1) enhance regional concentrations, (2) deploy human capital aligned with job pools, (3) develop innovation-enabling infrastructure, (4) increase spatial efficiency, and (5) create effective public and civic culture and institutions.

As the agency tries to change course toward more effective innovation, he said, it develops a framework around jobs and innovation partnerships. EDA is a small agency, he reminded his audience, with a budget of only about $300 million—a mere “rounding error” for a large agency. “We aren’t going to move the macro-economic needle of the country’s GDP,” he said. “But what we can do is be selective and effective with the investments we make. We’ve tried to target our money at key sectors of innovation ecosystems, to use best practices, and to use competitions to drive demonstration projects. Included in the Jobs and Innovation Partnership are the following:

- Jobs and Innovation Accelerator Competition.

- i6 Green Challenge.

- Regional Innovation Acceleration Network.

- National Economic Cluster Map.

- 21st Century Innovation Infrastructure.

Making Selective Investments

For the i6 challenge, Mr. Fernandez said, which is open to proof-of-concept centers, the Austen Bio-Innovation Institute in Akron was one of the recent winners. EDA also invested in a modeling simulation pilot project for advanced manufacturing in the Midwest. “Those are the kinds of selective investments we want to make that can help demonstrate best practices and be catalytic. We’ve also learned listening to our stakeholders that you need a lot of persistence and dedication to get through the maze in applying for Federal resources. We need an easier interface and from the Federal side a common framework to bring these fragmented programs together. This is a model the stakeholders and the customer want.” He said that EDA was working with 15 other Federal agencies on a Jobs Innovation Accelerator, a $30 million competition for 20 pilot sites to develop locally chosen public-private partnerships around specific cluster initiatives.

Mr. Fernandez closed by reaffirming that “the solutions we need to drive innovation in our economy aren’t going to be born in Washington. They’re going to be born in communities like Cleveland, like my hometown of Bloomington, Indiana, and other places where the ideas are. That’s why these bottom-up strategies really matter, and why the work you do every day is important to the nation’s success at innovation. We look forward to being your partner in that.”

DISCUSSION

Dr. Lefton affirmed the value of “growing the pie rather than competing with one another.” This, he said, is a central element of what clusters are designed to do. “If we create regional, statewide clusters, we can grow the pie, and that means developing ecosystems and leveraging what we have to our best advantage.” He agreed with Ms. Brachman’s conclusion that “it may mean getting rid of some government bureaucracy and divisions that hold back rather than facilitate cluster development.” He then turned to the example of the Cleveland Foundation and its role in facilitating cluster development.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN OHIO: THE ROLE OF COMMUNITY FOUNDATIONS

Ronn Richard

Cleveland Foundation

Mr. Richard said he would describe the Cleveland Foundation’s overall approach, its key programs, and its progress to date. He added that “You may be surprised by the breadth and depth of our efforts.”

The Cleveland Foundation, he began, was the world’s first community foundation and Ohio’s largest grant making organization. It was created in 1914, and since then its assets have grown to $1.9 billion. Last year it disbursed about $85 million to Greater Cleveland, primarily to nonprofit programs and organizations. “But we also leveraged a lot of money from national foundations and provided leadership,” he said, “so I think our results exceed that figure.”

Mr. Richard said that when he arrived at the Cleveland Foundation from Washington, DC, eight years ago, virtually all of its grants supported education, social services, and civic affairs. “Those are all wonderful and important recipients,” he said. “But we felt that a big piece was missing—economic development. The foundation’s board agreed that if we didn’t do something about economic development, there might not be an art museum to give money to in 30 years. So we made this a major priority, if not the major priority, for the Cleveland Foundation.”

A Shift From Responsive to Proactive

Historically, some two-thirds of the foundation’s grantmaking was “purely responsive,” he said. “The remainder was proactive, where we would see a need or opportunity and create something. Today, two-thirds of our grants are proactive programs that we start. This allows us to make a meaningful impact on our community, and again, economic development is at the top of the list.”

The foundation has a multi-pronged approach. One is to increase Cleveland’s global standing by attracting foreign operations and helping local companies find new markets overseas. Another tack is to nurture new companies and growth industries. Toward that end, it plays a significant role in helping Cleveland gain a stronger position in the advanced energy and bioscience industries. To accomplish this, it involves itself with “public policy, launching new programs and organizations, and pursuing strategic partnerships with existing stakeholders locally, especially our large anchor institutions.”

Mr. Richard said that the foundation’s economic development efforts are designed to align with important issues facing the country, especially energy, education, and national security. “And when we strengthen one of those, we strengthen all of them.” For example, he said, the efforts to strengthen education, at both local and state levels, also help create a home-grown work

force, which is necessary for the economy to thrive. This work force helps sustain the talent to staff the military, operate high-tech national security systems, and staff private sector companies.

A New Focus on Energy

Mr. Richard said that he regarded energy as “the most important issue facing our country today,” and that advanced energy development was a top priority because of its direct effects on every major sector, including transportation, food supply, the environment, and jobs. Given Cleveland’s manufacturing history and expertise and its location on the Great Lakes, the region has the potential to assume a leadership position in advanced energy. “This is a $10 billion industry that’s growing by double digits and creating tens of thousands of jobs worldwide,” he said. “But we have to act swiftly and boldly if we’re to win the race and realize the potential of advanced energy.” Unfortunately, he said, Cleveland is where it is today “because we totally missed the IT revolution. We cannot afford to miss the next one.” Therefore, the foundation has been very active in attempting to ensure that Cleveland is “a green city on a blue lake” and a national player in advanced energy.

To capture this opportunity, the foundation’s board agreed to make energy a major focus, hiring Richard Stuebi and becoming the “first and only community foundation out of 717 in the U.S. to have a full-time senior person for economic development and for energy.” An early project was to create a map that showed the wind on Lake Erie to be sufficient for a major wind farm. With partners, it helped erect a windmill in front of the Great Lakes Science Center “to remind people that there was a new industry a-comin’,” and hired its first lobbyist, who helped pass a renewable energy portfolio standard, or RPS, bill in the legislature, which was signed by the governor. With these steps, Mr. Richard acknowledged, “public policy became important to us.” He added that because Ohio ranks fourth in the nation in power consumption, policy measures like an RPS bill, which now requires one-quarter of the state’s energy to come from renewable sources by 2025, are vitally important.

The foundation also played a key role in the passage of Ohio House Bill 1, which enables municipalities to create Special Improvement Districts, or SIDs, for solar energy projects. Cleveland and 16 suburban municipalities established the first such SID in Ohio, and businesses are also installing solar projects. Most importantly, he said, the foundation secured backing from the city and the county to build an offshore wind demonstration project in Lake Erie. In September 2010, GE, Bechtel, and Cavallo Energy became partners in an initial 20-Mw project. “We hope to have the first turbines in the water by 2013,” he said, “and, hopefully, we’ll have hundreds if not thousands of turbines in the lake by 2030.”

The foundation has also worked to create a strong network of support for the renewables industry. It gave a $3.6 million grant to Case Western Reserve University to start the Great Lakes Energy Institute, with a focus on

energy storage. “This is critical to make solar and wind more competitive,” he said. Foundation support also goes to WIRE-Net to strengthen the nation’s supply chain for wind energy; to NorTech, a $700,000 grant to help create its Energy Enterprise initiative; and to the Lake Erie Energy Development Corporation (LEEDCo), to lead the wind project. The foundation also helped launch Ohio Cooperative Solar, which is providing solar energy on the rooftops of major regional anchor institutions.

Support for a Bioscience Industry

Mr. Richard turned to the foundation’s emphasis on the bioscience industry “that, like energy, has the potential for rapid growth and job creation.” Along with Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals, and Case Western Reserve, the foundation helped launch BioEnterprise, whose mission is to commercialize biomedical research and launch young companies by connecting them to investors and expertise. So far, BioEnterprise has helped recruit 100 companies in Northeast Ohio and attracted more than $1 billion in investment capital. The foundation also supports BioEnterprise in launching a Health Tech Corridor, planned as a concentration of biomedical, health care, and other technology companies hoping to benefit from proximity to health care institutions and academic centers. The foundation gave a $5 million grant, the largest single grant in its history, to Case Western Reserve to start the Center for Proteomic Medicine, and in 2005 helped launch JumpStart, an organization that provides entrepreneurs with mentors as well as money and financing connections. The Cleveland Foundation also played a key role in starting a Fund for the Economic Future, and remains as one of its funders.

A Partnership with Anchor Institutions

The foundation partners with existing anchor institutions to help them meet their needs and to help the economy. These include Case Western Reserve, Cleveland Clinic, and University Hospitals. “This is part of our place-based strategy,” Mr. Richard said. “We think another thing we need to do is help these large anchor institutions create jobs and spin off companies with their intellectual property rights and purchasing power of $3 billion a year, most of which goes outside the state at present. So we’ve been starting a series of new companies called the Evergreen Cooperative Companies that offer good-paying jobs to local residents, who also have the opportunity to build an ownership stake in these companies. The Evergreen Laundry is up and running, the solar collaborative I mentioned earlier is up and running, and soon we’ll have the largest commercial greenhouse in the country.”

The foundation has helped start 11 innovative, high-performing schools with the Cleveland public school system, including the Cleveland School of Science and Medicine, where he chairs the board. The school has a 100 percent

graduation rate, with many entering top universities, and Mr. Richard hopes that many will return to Cleveland to work in the anchor institution hospitals.

“We have a long way to go,” Mr. Richard said in summary, “and now we’re looking at what more we can do, given our balance sheet. We have about $2 billion, we’re looking to see how we can invest that money in local institutions and efforts that will give us a good return on investment but also have a double or triple bottom line for us.” Mr. Richard concluded by underlining the importance of philanthropy in the campaign for economic development. “We have wonderful foundations in this region, and they all have their oar in the water,” he said. “We’re all going in the same direction, and I hope we’ll really contribute to the success of the public and private sectors.”

DISCUSSION

A questioner asked for a good example of creating a cluster, and Dr. Lefton conceded that much more is known about the value of clusters than about how to create them—“especially in places with traditional economies, like Cleveland and Akron. I would probably point to Pittsburgh as one that is starting to take hold.”

Mr. Fernandez added that in addition to the well known examples of Silicon Valley, Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, and others, a successful life sciences and medical device cluster was started early in the 1980s in Indiana and has since grown in healthy fashion. The cluster is driven by an organization called Biocrossroads, a public-private partnership. Likewise, in Kansas is a strong aviation and advanced manufacturing cluster being driven by a several chambers of commerce. He said other solid examples are found, some of them in unexpected places, such as the strong cluster around Virginia Tech that was created with the help of tobacco settlement money. He said the EDA is now mapping many of these, which could make it easier to link to organizations that are building successful cluster initiatives.

Investing Across Borders

Dr. Lefton asked what the optimal size of a cluster is, and whether the area from Pittsburgh to Cleveland and Akron is too large for a viable cluster. Mr. Fernandez said he thought size was less an issue than “some of these archaic jurisdictional borders that get in the way of collaboration. The economy doesn’t follow those borders, and yet they often constrain us.” What the Federal government could do, he said, through competition and tools, is to “give local officials some ‘cover’ for co-investing with their neighbors. We all know we don’t really care much about borders on maps, especially the private sector, but when you try to co-invest, it is really hard.” For example, the mayor of Bloomington, he said, would be chastised for putting money in another county, even when it helped the region. He said that foundations could help overcome such boundaries issues.

Robert Schmidt, of Cleveland Medical Devices, said that one barrier to collaboration was the Ohio code that controls rights to discoveries. This is interpreted differently by and within different universities, he said, but it is often considered to mean that any invention that grows out of an activity within a university, even the use of a library or a laboratory, would be owned by the university. He said this had sometimes prompted his company to takes its business outside Ohio to conduct testing rather than use instrumentation in an Ohio university that might thereby claim ownership. He asked whether this law could be revised so that cluster activity could be promoted.

Dr. Lefton said that in northeast Ohio virtually all universities have a liberal policy that encourages tech transfer by leaving a “piece of the action” to the original investigator and a little to the university, and fosters collaboration between either of them and private business. “I think you’ll be seeing a modernization of thinking within universities to allow for smoother tech transfer. It’s clearly part of Governor Kasich’s plan for universities, and also part of ours.”