People forget things—a name, where they put their keys, a phone number—and yet what is dismissed as a minor inconvenience at 25 years of age can evolve into a momentary anxiety at 35, and a major source of personal worry at age 55 or 60. Forgetfulness at older ages is often equated with a decline in cognition—a public health issue that goes beyond memory lapses and one that can have significant impacts on independent living and healthy aging. The term “cognition” covers many mental abilities and processes, including decision making, memory, attention, and problem solving. Collectively, these different domains of cognition are critical for successfully engaging in the various activities involved in daily functioning such as paying household bills, following a recipe to cook a meal, and driving to a doctor’s appointment. As human life expectancy increases, maintaining one’s cognitive abilities is key to assuring the quality of those added years.

Cognitive aging is a public health concern from many perspectives. Individuals are deeply concerned about declines in memory and decision-making abilities as they age and may also be worried about whether these declines are early signs of a neurodegenerative disease, particularly Alzheimer’s disease. They may fear that cognitive decline will lead to a loss of independence and a reduced quality of life and health. Cognitive decline affects not only the individual but also his or her family and community, and an array of health, public health, social, and other services may be required to provide necessary assistance and support. Lost independence may stem from impaired decision making, which can reduce an individual’s ability to drive a car or increase the individual’s vulnerability to financial

abuse or exploitation. Cognitive impairment also affects society and the public’s quality of health and life.

At this point in time, when the older population is rapidly growing in the United States and across the globe, it is important to carefully examine what is known about cognitive aging, to identify the positive steps that can be taken to maintain and improve cognitive health, and then to take action to implement those changes by informing and activating the public, the health sector, nonprofit and professional associations, the private sector, and government agencies. In the past several decades rapid gains have been made in understanding the non-disease changes in cognitive function that may occur with aging and in elucidating the range of cognitive changes, from those that are normal with aging to those that are the result of disease; much remains to be learned yet the science is readily advancing.

This Institute of Medicine (IOM) study examines the public health dimensions of cognitive aging with an emphasis on definitions and terminology, epidemiology and surveillance, prevention and intervention, education of health professionals, and public awareness and education (see Box 1-1).

To complete this task the IOM appointed the 16-member Committee on the Public Health Dimensions of Cognitive Aging whose members have expertise in cognitive neuroscience, geriatric medicine and nursing, gerontology, neurology, psychology, psychiatry, behavioral sciences, communication, public health, epidemiology, social work, and ethics. The study was sponsored by the McKnight Brain Research Foundation, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Aging, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The Retirement Research Foundation, and AARP.

The committee held five meetings during the course of its work, two of which included public workshops during which a number of speakers provided their expertise on the study topics (see Appendix A). The committee also heard from various speakers at its first meeting in February 2014 and in public conference call meetings in August and September 2014. In addition to the input received through these workshops and meetings, the committee examined the scientific literature and other available evidence. The committee focused on providing a report for a broad audience, including the general public; health care and human services providers; local, state, and national policy makers; researchers; and foundations and nonprofit organizations.

WHAT IS COGNITION?

This report focuses on one aspect of health in older adults—cognitive health. Cognition refers to the mental functions involved in attention, thinking, understanding, learning, remembering, solving problems, and making decisions. It is a fundamental aspect of an individual’s ability to engage in

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

The Institute of Medicine will conduct a study to examine cognitive health and aging, as distinct from Alzheimer’s disease. The committee will make recommendations focused on the public health aspects of cognitive aging with an emphasis on the following:

- Definitions and terminology—The study will explore relevant definitions and terminology with consideration given to preventing unintended consequences of terminology.

- Epidemiology and surveillance—The focus of the study will be on identifying efforts needed to better understand the public health implications of cognitive aging and its risk and preventive factors, as well as the development of relevant surveillance or monitoring tools and methodologies.

- Prevention and intervention opportunities—The study will examine opportunities for prevention and intervention taking into account the multiple aspects of enhancing cognitive capacity, prevention of impairment, amelioration of cognitive decline, and promoting cognitive resilience. This will include relevant research on human behavior change and the evidence-based approaches needed to ensure the retention of healthy practices to maintain cognitive health and remediate cognitive decline.

- Education of health professionals—This study will explore the education of health professionals related to cognitive health and decline and will identify examples of best practices for educating health professions to ensure high quality care and education for older adults and their families about cognitive aging and its possible consequences.

- Public awareness and education—The study will consider new approaches for enhancing awareness and disseminating information (with cultural, ethical, and health literacy considerations) to the public and to older adults and their families and caregivers.

The committee will hold information-gathering workshops open to the public during the course of its work. The report will not focus on setting an agenda for basic and biomedical science research as this has been the topic of recent reports and forums. Biomedical research will, however, inform the committee’s deliberations and will serve as the foundation for the evidence base of the report.

activities, accomplish goals, and successfully negotiate the world. Although cognition is sometimes equated with memory, cognition is multidimensional because it involves a number of interrelated abilities that depend on brain anatomy and physiology. Distinguishing among these component abilities is important since they play different roles in the processing of information and behavior and are differentially affected by aging.

While cognitive abilities do not neatly map to single discrete regions of the brain, generalizations can be drawn between brain regions and key

cognitive abilities that individuals need for their day-to-day function, wellbeing, and flourishing. For example, decision making, organizing, and planning, and other related processes, are collectively referred to as “executive function.” The prefrontal cortex is the region of the brain that is active in executive functions, such as the planning and multitasking required for cooking a meal. In contrast, memory, such as is involved in remembering the list of food items needed at the supermarket, is largely controlled by the hippocampus. Other brain areas play key roles in other functions. Clinicians use different tests to measure and evaluate various cognitive dimensions depending on the type of cognition or brain region (see Chapter 2).

THE INTERSECTION OF COGNITION AND AGING

What Is Cognitive Aging?

The committee provides a conceptual definition of cognitive aging as a process of gradual, ongoing, yet highly variable changes in cognitive functions that occur as people get older. Cognitive aging is a lifelong process. It is not a disease or a quantifiable level of function. However, for the purposes of this report the focus is primarily on later life. In the context of aging, cognitive health is exemplified by an individual who maintains his or her optimal cognitive function with age.

Box 1-2 provides the committee’s characterization of cognitive aging. Cognitive aging is too complex and nuanced to define succinctly, and therefore it is appropriately characterized through this longer description. Efforts are needed to develop operational definitions of cognitive aging in order to allow comparisons across studies (see Chapter 3).

Prior Terminology and Definitions

The literature on cognitive aging includes a wide array of terms to describe the various aspects of cognitive aging. For instance, Rowe and Kahn (1987) differentiated “usual aging” from “successful aging.” “Usual cognitive aging” referred to such commonly found changes as reductions in processing speed and working memory, and also common pathological changes, such as those associated with cardiovascular disease. In contrast, the phrase “successful aging” was used to refer to the amelioration or prevention of changes that have a substantial and negative impact, often by adopting a healthy lifestyle. Rowe and Kahn argued that scientists, physicians, and the general public were all too ready to accept that significant and deleterious changes associated with age were inevitable. This complacency, in their view, ignored both the great variation in changes with age as well as the variation over time within an individual, and it undermined

BOX 1-2

Characterizing Cognitive Aging

-

Key Features:

- Inherent in humans and animals as they age.

- Occurs across the spectrum of individuals as they age regardless of initial cognitive function.

- Highly dynamic process with variability within and between individuals.

- Includes some cognitive domains that may not change, may decline, or may actually improve with aging, and there is the potential for older adults to strengthen some cognitive abilities.

- Only now beginning to be understood biologically, yet clearly involves structural and functional brain changes.

- Not a clinically defined neurological or psychiatric disease such as Alzheimer’s disease and does not inevitably lead to neuronal death and neurodegenerative dementia (such as Alzheimer’s disease).

-

Risk and Protective Factors:

- Health and environmental factors over the life span influence cognitive aging.

- Modifiable and non-modifiable factors include genetics, culture, education, medical comorbidities, acute illness, physical activity, and other health behaviors.

- Cognitive aging can be influenced by development beginning in utero, infancy, and childhood.

-

Assessment:

- Cognitive aging is not easily defined by clear thresholds on cognitive tests since many factors—including culture, occupation, education, environmental context, and health variables (e.g., medications, delirium)—influence test performance and norms.

- For an individual, cognitive performance is best assessed at several points in time.

-

Impact on Daily Life:

- Day-to-day functions, such as driving, making financial and health care decisions, and understanding instructions given by health care professionals, may be affected.

- Experience, expertise, and environmental support aids (e.g., lists) can help compensate for declines in cognition.

- The challenges of cognitive aging may be more apparent in environments that require individuals to engage in highly technical and fast-paced or timed tasks, in situations that involve new learning, and in stressful situations (i.e., emotional, physical, or health-related), and may be less apparent in highly familiar situations.

the search for reversible causes of such changes. The committee appreciates the important distinctions made by Rowe and Kahn, but it decided not to adopt the term “successful aging” because it may suggest a value judgment regarding those with greater or lesser preservation of cognitive capacity.

Similarly, the committee did not adopt the term “normal aging” because it is confusing. Some authors use this term to refer to standard or common aspects of cognitive aging (Aine et al., 2011), while others suggest that “normal” aging is the optimal state and refers to those aspects of aging change that remain when all disease-related changes have been ruled out (Jagust, 2013). (A detailed discussion of the development of norms in aging research is provided in Chapter 2.) Despite variability in the terminology across investigators and clinicians, there is wide agreement that preserving cognitive function is a key component of desirable aging (Warsch and Wright, 2010).

The committee uses the term “cognitive aging” to emphasize that the human brain changes with age, both in its physical structures and in its ability to carry out various functions. Indeed, it would be surprising if the brain did not age, given that all other organs and body structures age. Kidneys and muscles, for example, show a range of age-related changes in structure and function (Cohen et al., 2014; Keller and Engelhardt, 2013). And it is not only humans whose brains age. A considerable body of literature demonstrates that there is remarkable consistency across mammalian species in age-related neural and cognitive changes (Samson and Barnes, 2013; also see Chapter 2).

The brain is the locus for a vast array of functions, including reasoning, emotion, memory, judgment, sensory processing, learning, and motor skills. These many brain functions and the neural structures and networks that support them change at different rates and in different ways over time, with the particular changes based on a large number of interacting factors, including genetic makeup, education, environment, lifestyle, and trauma. A clear body of evidence indicates that as individuals age a decline occurs in specific brain functions that cannot be attributed to disease processes in the brain, such as neurodegeneration from Alzheimer’s disease or stroke. For instance, most older adults process information less quickly than they did when they were younger (Birren, 1970). Researchers face a daunting task in distinguishing between changes that are the consequences of aging and those that are attributable to specific neurological diseases and conditions, which may or may not have potentially reversible attributes.

What Are the Potential Impacts of Cognitive Aging?

Age-related changes in cognition can affect not only memory but also decision making, judgment, processing speed, and learning. (For more details on the many elements of cognition, see Chapter 2.) These changes can

in turn affect an older person’s capacity to live independently, to preserve a sense of identity grounded in autonomy, and to pursue treasured activities. The more that a society values an ethic of independence and a respect for autonomy, the more cognitive aging will be perceived as a social, cultural, and individual challenge. In fact, some people have reported that they are reluctant to tell their physicians or family members about their difficulties with cognition out of fear that they will lose their independence or their driving privileges (Ralston et al., 2001).

In a 2012 survey of its members, AARP found that “staying mentally sharp” was a top concern of 87 percent of respondents (AARP, 2013). Changes in cognition also have the potential to affect health directly by impairing a patient’s ability to take the proper medication dose on the correct schedule or to understand risks and benefits when choosing a treatment option or health insurance plan (IOM, 2014).

However, identity is shaped by a person’s capacity for interdependence as much as it is for a capacity for independence. Each person is defined by his or her relationships with family, colleagues, co-worshipers, and communities. The ability to help others, to collaborate, and to, at times, receive help are crucial human qualities. Ironically, the ability to appropriately seek and accept help when needed can be a critical factor in maintaining independence. One key message for this report is that although the brain will change with age, numerous opportunities exist to prevent, ameliorate, or adapt to cognitive changes. These opportunities can allow older adults to continue to function both independently and interdependently.

Family members of older adults also worry about how their loved one’s changes in cognition could affect their daily functioning. A 2010 survey found that 40 percent of children with parents age 65 years or older were concerned that their parents would have difficulty handling their personal finances (Investor Protection Trust, 2015).

Although most of the focus on cognitive aging is on its negative implications, noteworthy positive changes also can occur as the brain ages. For example, wisdom and knowledge increase with age (Grossmann et al., 2010), and happiness follows a U-shaped curve relative to age, with people reporting they are happiest in youth, less happy in midlife, and happiest again much later in life (Stone et al., 2010). Furthermore, levels of stress, worry, and anger all decline with increasing age (Stone et al., 2010).

Various groups and industries have taken note of the public health and societal impacts of cognitive changes in later life and are attempting to minimize the negative effects of cognitive aging, to make more resources available to more people, and to raise public knowledge. Examples of this heightened attention can be seen in actions by government at the federal, state, and local levels; by nonprofit organizations focused on older adults; and by companies in the relevant industries, including the financial services industries and the physical activity, transportation, food, and insurance in-

dustries (see Chapter 6). Given the demographics and the aging of society (see section below), the market for cognitive-related sales is significant, and older adults and their families will need to make evidence-based decisions.

CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS

The population of the United States, like that of many other countries, is getting older. Thus, cognitive aging will affect an ever-increasing number and proportion of Americans. Life expectancy in the United States has increased dramatically over the past century. In 1900, the average life expectancy at birth was 46.3 years for men and 48.3 years for women; by 2010 it had increased to 76.2 years for men and 81.0 years for women (NCHS, 2014). While the mortality rate among children and young adults has decreased, thanks to a variety of advances, age-adjusted mortality rates have also declined in the population over age 65 years (Hoyert, 2012). Decreases in mortality are attributable to, among other factors, reductions in smoking, better control of chronic diseases (e.g., especially heart disease), and improved education (Cutler et al., 2007).

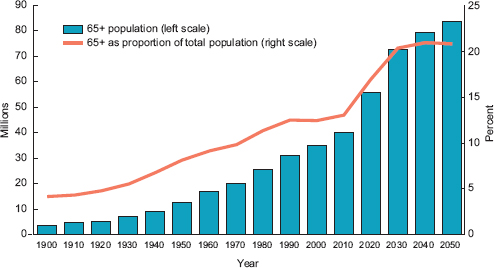

Increased life expectancy, changes in birth and mortality rates, and other factors are leading to major changes in the demographic composition of the U.S. and global population. In 1900, 4.1 percent of the U.S. population was 65 years or older (just over 3 million people); by 2012 that age group accounted for 13.7 percent of the population (more than 40 million people) (AoA, 2013; West et al., 2014). By 2050 people 65 years and older are expected to make up 21 percent of the U.S. population (see Figure 1-1; U.S. Census Bureau, 2012b). The “oldest old” demographic—people age 85 years and older—is expected to increase from 6.3 million (1.96 percent of the population) in 2015 to just over 18 million (4.5 percent) in 2050 (Suzman and Riley 1985; U.S. Census Bureau, 2012a,b). In the past three decades the percentage of the population that is age 90 years and older has tripled, and in the next four decades it is expected to more than quadruple (He and Muenchrath, 2011).

Similar aging trends are occurring in developed countries around the globe. Japan’s 65-years-and-older population is almost one-fourth of its total population, with similar percentages seen in Germany and Italy (both more than 20 percent) (Jacobsen et al., 2011). Even though the public health implications of cognitive aging may be unique for each country due to their distinct social, cultural, and economic conditions, the challenges and opportunities that these countries face are all related.

Diversity

In addition to increasing in total number, the U.S. population 65 years and older is expected to diversify racially and ethnically by 2050. In 2010,

FIGURE 1-1 Population age 65 years and older, 1900 to 2050.

SOURCE: West et al., 2014.

the non-Hispanic white demographic made up 80 percent of this group, but this share is projected to decrease to 58 percent by 2050. While the Hispanic population accounted for 7 percent of the 65-years-and-older population in 2010, it is projected to grow to 20 percent in 2050 (increasing from 3 million individuals in 2010 to 17.5 million in 2050); the black population will account for 12 percent of the 65-years-and-older population in 2050, up from 9 percent in 2010 (from 3.4 million to 10.5 million people); and the Asian population will increase from 6 percent to 9 percent of the 65-years-and-older population (from 1.3 million in 2010 to 7.5 million in 2050) (FIFARS, 2012). This increasing diversity of the population calls for a focus on improving cognitive measurement techniques and the development of appropriate metrics and interventions for diverse ethnic, cultural, and racial groups as part of the broad effort to improve cognitive health in the aging population.

Health Status

The health status of older Americans has improved over the past several decades (West et al., 2014). In 2010 roughly three-fourths of adults age 65 years and older reported their health status to be “excellent,” “very good,” or “good” (Schiller et al., 2012). However, the percentage of adults reporting excellent or very good health decreases with age.

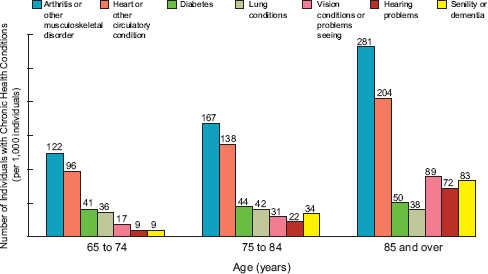

Despite good self-rated health, a large majority of older adults have at least one chronic disease (e.g., hypertension, arthritis) that requires ongo-

FIGURE 1-2 Limitations of activity caused by chronic health conditions by age, 2006–2007 (per 1,000 individuals).

NOTE: Data are from the 2006–2007 National Health Interview Surveys, which cover the civilian noninstitutionalized population.

SOURCE: West et al., 2014.

ing care. In addition, many older adults experience one or more clinical conditions that do not fit into discrete disease categories (e.g., incontinence, frailty) (see Figure 1-2; West et al., 2014). The care needed for these syndromes and diseases—both acute and chronic—presents older adults with decisions that will lead to ethical and economic outcomes that can substantially affect their well-being and quality of life. Cognitive aging can add to the challenges that older adults face when making these decisions.

CROSS-CUTTING THEMES

Cognitive aging is a broad topic with sweeping implications and challenges. This report focuses on the public health dimensions of cognitive aging and touches only briefly on the numerous basic science questions and neuropsychological assessment challenges related to cognitive aging. In addressing the public health challenges of cognitive aging, the committee identified several cross-cutting themes and key messages (see Chapter 7):

- Cognitive health should be promoted across the life span. Actions can be taken by individuals to help maintain cognitive health.

- Healthy cognition facilitates an individual’s capacity to function. It allows people to learn, to make appropriate choices, and to express current and future preferences. Cognitive abilities enable people to accomplish the tasks of daily living, to understand information and apply it to personal situations through appreciation and reasoning, and to effectively assess emotions such as trust. It enables people to maintain the essence of self. Actions to maintain cognitive health are discussed throughout the report.

- Cognition is memory plus much more; there are multiple dimensions of cognition. Cognitive abilities range from the capacities for decision making and processing time to memory, attention, and more (see Chapter 2).

- Cognitive functioning levels vary among individuals and throughout the life span. From infancy through young adulthood and old age, the brain continues to change. Within the predictable level of change at each stage of life, there is also great variability among individuals.

- Cognitive function is affected by multiple factors. Neuroplasticity persists throughout the life span so that there is potential for older adults to strengthen cognitive abilities. Due to the complexity of the human brain, numerous risk and protective factors may affect cognitive abilities (including genetics, physical activity, traumatic brain injury, sleep quality, comorbidities, acute illness, delirium, and medications) (see Chapters 4A, 4B, 4C).

- Cognitive changes are not necessarily signs of neurodegenerative disease (such as Alzheimer’s disease) or other neurological diseases. There are many potential causes of cognitive decline, some of which may be at least partly preventable or treatable (e.g., recent changes in medications associated with short-term delirium).

- Cognitive aging can affect daily activities and independent living. The significance of cognitive aging can be seen especially in its potential effects on daily tasks and decision making. Cognitive decline caused by cognitive aging may occur gradually and with few overt symptoms or signs. As a result, individuals or their close friends or family may not notice deterioration in driving, financial decisions, food choices, and other everyday activities until it becomes severe.

- Age affects all organ systems. The brain, as with all organs, is affected by aging. Over the span of life, connectivity is lost between some neuronal synapses and other changes occur.

- Aging can have positive effects on cognition. The experiences and knowledge gained over a lifetime can provide individuals with positive cognitive benefits (e.g., wisdom learned from experience).

OVERVIEW OF THE REPORT

This report explores the multiple issues involved in considering cognitive aging from a public health perspective. Chapter 2 explores the challenges of characterizing and measuring changes in cognition, highlights the impact of cognitive aging on daily function, and discusses the variability among individuals particularly as related to setting norms. Chapter 3 focuses on collecting and understanding population-based data on cognitive aging. Chapters 4A, 4B, and 4C provide an overview of the epidemiologic research on risk and protective factors for cognitive aging and discuss the research on a range of prevention and treatment interventions. Chapter 5 focuses on health care’s response to cognitive aging, with discussions on increasing the abilities of health professionals to assess cognitive aging and to use wellness visits to discuss these issues with their patients. The community’s response to cognitive aging is discussed in Chapter 6, which describes the wide variety of resources that are currently available and that need to be developed for older adults and their families facing decisions on personal finances, driving, technology, and cognitive-related products. Chapter 7 offers key messages on cognitive aging and highlights efforts that are needed to raise awareness of these issues among members of the general public. The report concludes in Chapter 8 with a call to action for individuals, government agencies, private-sector corporations, and nonprofit and professional organizations.

REFERENCES

AARP. 2013. 2012 member opinion survey issue spotlight: Interests and concerns. http://www.aarp.org/politics-society/advocacy/info-01-2013/interests-concerns-member-opinion-survey-issue-spotlight.html (accessed December 4, 2014).

Aine, C. J., L. Sanfratello, J. C. Adair, J. E. Knoefel, A. Caprihan, and J. M. Stephen. 2011. Development and decline of memory functions in normal, pathological and healthy successful aging. Brain Topography 24(3-4):323-339.

AoA (Administration on Aging). 2013. A profile of older Americans: 2013. http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/Index.aspx (accessed December 5, 2014).

Birren, J. E. 1970. Toward an experimental psychology of aging. American Psychologist 25(2):124-135.

Cohen, E., Y. Nardi, I. Krause, E. Goldberg, G. Milo, M. Garty, and I. Krause. 2014. A longitudinal assessment of the natural rate of decline in renal function with age. Journal of Nephrology 27(6):635-641.

Cutler, D. M., E. L. Glaeser, and A. B. Rosen. 2007. Is the U.S. population behaving healthier? National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 13013. http://www.nber.org/papers/w13013 (accessed December 5, 2014).

FIFARS (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics). 2012. Older Americans 2012: Key indicators of well-being. http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2012_Documents/docs/EntireChartbook.pdf (accessed December 5, 2014).

Grossmann, I., J. Na, M. E. Varnum, D. C. Park, S. Kitayama, and R. E. Nisbett. 2010. Reasoning about social conflicts improves into old age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107(16):7246-7250.

He, W., and M. N. Muenchrath. 2011. 90+ in the United States: 2006-2008. U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey Reports. http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/acs-17.pdf (accessed December 5, 2014).

Hoyert, D. L. 2012. 75 years of mortality in the United States, 1935-2010. NCHS Data Brief, No. 88. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db88.pdf (accessed December 5, 2014).

Investor Protection Trust. 2015. IPT activities: 06.15.2010—IPT Elder Investor Fraud Survey: 1 out of 5 older Americans are financial swindle victims. http://www.investorprotection.org/ipt-activities/?fa=research (accessed February 19, 2015).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2014. Health literacy and numeracy: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jacobsen, L. A., M. Kent, M. Lee, and M. Mather. 2011. America’s aging population. Population Bulletin 66(1). http://www.prb.org/pdf11/aging-in-america.pdf (accessed December 5, 2014).

Jagust, W. 2013. Vulnerable neural systems and the borderland of brain aging and neurodegeneration. Neuron 77(2):219-234.

Keller, K., and M. Engelhardt. 2013. Strength and muscle mass loss with aging process. Age and strength loss. Muscles, Ligaments, and Tendons Journal 3(4):346-350.

NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics). 2014. Health, United States, 2013: With special feature on prescription drugs. 2013. http://www.cdcgov/nchs/data/hus/hus13.pdf (accessed December 5, 2014).

Ralston, L. S., S. L. Bell, J. K. Mote, T. B. Rainey, S. Brayman, and M. Shotwell. 2001. Giving up the car keys. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics 19(4):59-70.

Rowe, J. W., and R. L. Kahn. 1987. Human aging: Usual and successful. Science 237(4811): 143-149.

Samson, R. D., and C. A. Barnes. 2013. Impact of aging brain circuits on cognition. European Journal of Neuroscience 37(12):1903-1915.

Schiller, J. S., J. W. Lucas, B. W. Ward, and J. A. Peregoy. 2012. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_252.pdf (accessed January 8, 2015).

Stone, A. A., J. E. Schwartz, J. E. Broderick, and A. Deaton. 2010. A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107(22):9985-9990.

Suzman, R., and M. W. Riley. 1985. Introducing the “oldest old.” The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly: Health and Society 63(2):177-186.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2012a. Table 2. Projections of the population by selected age groups and sex for the United States: 2015 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2012/summarytables.html (accessed December 5, 2014).

———. 2012b. Table 3. Percent distribution of the projected population by selected age groups and sex for the United States: 2015-2060. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2012/summarytables.html (accessed December 5, 2014).

Warsch, J. R., and C. B. Wright. 2010. The aging mind: Vascular health in normal cognitive aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 58(Suppl 2):S319-S324.

West, L. A., S. Cole, D. Goodkind, and W. He. 2014. 65+ in the United States: 2010. U.S. Census Bureau Special Studies. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p23-212.pdf (accessed January 8, 2015).