3

Population-Based Information About Cognitive Aging

While a great deal of research has examined the occurrence, causes, natural history, pathogenesis, and clinical management of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, less attention has been paid to cognitive aging per se, particularly from a public health perspective. Population-based information about the nature and extent of cognitive aging provides a basis for building public awareness and understanding and can be used to engage individuals and their families in maintaining cognitive health; to inform health care professionals, financial professionals, and others as they educate and advise their older patients and clients; and to guide program development and implementation.

This chapter provides a brief overview of available population-based information about cognitive aging in the United States and discusses challenges and next steps in collecting, analyzing, and disseminating needed information that is not currently available. The chapter addresses the following questions:

- How does a life-course perspective help inform the understanding of cognitive aging?

- What does population-based research show about the cognitive status of older Americans, the amount and types of cognitive change that occur in individuals as they age, and older adults’ awareness and perceptions about these changes?

- What are the challenges in collecting population-based information about cognitive aging?

- What additional research is needed in order to increase knowledge about cognitive aging for public health and related purposes?

Although information about cognitive aging is available from a variety of sources, this chapter focuses mainly—although not entirely—on information derived from surveys and studies that have been conducted in representative U.S. population samples, including national, regional, and local populations. The focus on information from U.S. sources is not intended to ignore the important worldwide research literature but rather to maximize the relevance of the information to U.S. programs and policies. Likewise, the focus on surveys and studies conducted in representative population samples is not intended to ignore the important scientific and clinical findings derived from research employing other kinds of samples, including samples of community volunteers and patients in clinical settings, such as physician’s offices and health care systems. From a public health perspective however, information based on findings from representative population-based samples is especially relevant and useful.

A major challenge in assembling population-based information about cognitive aging is that most analyses of population data on cognition in older adults have focused on moderate and severe cognitive impairment, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. This focus has certainly yielded valuable information, such as estimates that 11.2 to 13.9 percent of older Americans have dementia (Kasper et al., 2014; Plassman et al., 2007), including 9.7 to 11.7 percent who have Alzheimer’s disease (Hebert et al., 2013; Plassman et al., 2007).1 But, much less attention has been paid to population data on the less severe cognitive changes experienced by the majority of older adults—changes that may affect important day-to-day activities, such as driving, making financial decisions, and managing medications. The resulting gaps in understanding of the larger picture of changes in cognition with aging underscore the need for population-based information on cognitive aging apart from moderate and severe cognitive impairment, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease.

LIFE-COURSE PERSPECTIVE

In the past few decades, developments in life-course epidemiology have led to a greater understanding of health and disease as they evolve across the life span. Life-course epidemiology studies health in a social, environmental, and cultural context and examines both the factors that affect health and the impact that health has on other outcomes for individuals throughout their lives. A life-course perspective is informative when ap-

____________

1These and other estimates of the prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease vary because of differences among population-based studies in the definitions of the conditions studied, the tests used to measure them, the age and other characteristics of sample members, and other factors (Brookmeyer et al., 2011; Rocca et al., 2011).

plied to cognitive aging because the cognitive status of older adults reflects not only the changes that occur in older age but also the effects of social and environmental factors and health-related events that occurred earlier in life. A life-course approach emphasizes the role of early brain and cognitive development and the general social and environmental threats and enhancements to that development among infants and children (Hofer and Clouston, 2014). This approach also acknowledges the effects of health-related events and risk factors that occur in adolescence and young and middle adulthood. Examples include head or bodily trauma due to automobile crashes or military combat; major mental illnesses, such as affective disorders, substance abuse, or various psychoses; cerebro-vascular disease risk factors, such as uncontrolled hypertension and lipid disorders; toxic maternal exposures; and physiochemical exposures of hazardous occupations. All of these factors help explain the wide differences in cognitive status observed among individuals as they age. While not all early events and risk factors that can affect cognition in older adults are fully preventable, paying greater attention to the adverse events of human development (such as the physical and social environments associated with poverty or the cognitive decrements associated with severe mental illnesses) may improve clinical and public health interventions and policies and may lead to more optimal human development.

NATURE AND EXTENT OF COGNITIVE AGING IN THE UNITED STATES

In order to understand cognitive aging in the context of whole communities and populations, it is necessary to carry out studies of representative samples of those populations. Many ongoing and completed surveys and studies conducted with samples of national, regional, and local populations in the United States include items that measure cognition and cognition-related factors. Some survey items measure survey respondents’ cognition directly, resulting in what is sometimes referred to as objective information about cognition. Other survey items measure survey respondents’ awareness and perceptions about their cognition, resulting in what is often referred to as subjective information about cognition. Box 3-1 provides examples of these two kinds of survey items.

A recent review identified more than 40 U.S. surveys and studies that have used valid and reliable measures of cognition in adults age 50 and older (Bell et al., 2014). Approximately half of these surveys and studies have been conducted in representative samples of national, regional, or local populations. Some of the surveys and studies use only a few items, including validated brief mental status tests or items drawn from those tests, to measure cognition directly. Others use more extensive batteries of

BOX 3-1

Survey Items Used to Measure Cognition

Direct Measures of Cognition

These survey items often use standardized cognitive tests that ask the respondent to answer questions intended to measure various components of cognition, such as memory, orientation, executive function, vocabulary, and reasoning. Memory is often measured by asking a respondent to listen to a list of words and then repeat all of the words remembered (immediate word recall). After a specified time interval, the respondent is again asked to repeat all of the words remembered (delayed word recall). Orientation may be measured by asking a respondent for the current day, month, year, and day of the week and the name of the current president. Other commonly used survey items ask respondents to name common objects, such as scissors; to name as many different animals as they can in a minute or two; to complete one or more partial sentences; to count backward from 100 by 7s; and to identify a missing number in a series of numbers. (See Box 2-1 in Chapter 2 for additional information about commonly used cognitive tests.)

Measures of Awareness and Perceptions About Cognition

These survey items may ask respondents to rate their memory (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) or ask whether they have difficulty remembering, concentrating, making decisions, or learning something new. Respondents may be asked whether they have noticed changes in their thinking ability or whether their memory is better, the same, or worse than at a specified time in the past. Similarly, they may be asked whether they have experienced confusion or memory loss and whether it is happening more often or getting worse. Related measures include how an individual feels about and adapts to these perceived changes in cognitive function.

neuropsychological tests. Many also measure respondents’ awareness and perceptions about their own cognition. Still others measure respondents’ awareness and perceptions about their cognition but do not measure cognition directly.

Table 3-1 provides descriptive information about five ongoing surveys and studies that are being conducted in nationally representative U.S. samples. These surveys and studies are used as examples throughout this chapter to illustrate the kinds of information about cognitive aging that are being or could be collected in population-based research. Other surveys and studies that are being or have been conducted in the United States also provide information about cognitive aging. For example, the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (EPESE), which was conducted in four states, provides information about the proportion of adults age 65 years and older who had errors on a brief cognitive test (Cornoni-Huntley et al., 1986, 1990). Appendix B lists not only the surveys and studies shown in Table 3-1 but also many of these other research efforts.

TABLE 3-1 Selected Surveys and Studies Conducted in Representative Samples of the U.S. Population That Collect Information About Cognition in Adults

| Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) | Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | Midlife in the United States Study (MIDUS) | National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) | |

| Primary sponsoring agency | CDC | NIA and SSA | NIA | NIA | NCHS |

| Conducted by | State health departments | University of Michigan | University of Wisconsin–Madison | Johns Hopkins University | NCHS |

| Sample size | About 500,000 annually | More than 26,000 every 2 years | 7,100 (MIDUS I) 4,300 (MIDUS II) | 8,200 in 2011 | About 5,000 annually |

| Sample criteria | Age: 18 years and older | Age: 50 years and older | Age: 25 to 74 years (MIDUS I) Age: 32 to 84 years (MIDUS II) | Age: 65 years and older Medicare enrollee | All ages |

| Includes nursing home residents | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Measures cognition directly | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Measures awareness and perceptions about cognition | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Collects information about sample person’s cognition from a proxy/informant | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) | Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | Midlife in the United States Study (MIDUS) | National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) | |

| Collects longitudinal information about cognition | No | Yes, every 2 years | Yes (MIDUS II and a subsample from MIDUS I) | Yes, annually | No |

| Conducted in person, by telephone, other | Telephone | In-person and telephone interviews with survey subject and a proxy | Telephone and self-administered questionnaire | In-person interviews with the survey subject or a proxy respondent | In-person interviews and health examinations in mobile centers |

| Asks about activities of daily living (ADLs) | Dressing and bathing only | All 5 ADLs | Dressing and bathing only | All 5 ADLs | Dressing, bathing, transferring from bed to chair, and eating |

| Asks about instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) | Shopping only | All 7 IADLs | No | Shopping, food preparation, laundry, managing finances, managing medications | Shopping, food preparation, laundry, housekeeping, managing finances, managing medications |

| Asks about other physical activity limitations | Walking and climbing stairs | Walking, climbing stairs, crouching, stooping, kneeling, lifting, getting up from a chair | Walking, climbing stairs, stooping, kneeling, lifting | Walking, climbing stairs, kneeling, lifting | Walking, climbing stairs, crouching, stooping, kneeling, lifting, getting up from a chair |

| Asks about race/ethnicity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Asks about veteran status | “ever served in the military” | “ever served in the military” | No | Yes | Yes |

| Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) | Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | Midlife in the United States Study (MIDUS) | National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) | |

| Asks about physical activity and exercise | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Asks about cardiovascular risk factors: hypertension, diabetes, smoking | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Asks about social engagement | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Asks about difficulty participating in social activities or lack of such participation |

NOTES:

Activities of daily living (ADLs): bathing, dressing, transferring from bed to chair, using the toilet, and eating. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs): using the telephone, shopping, food preparation, laundry, housekeeping, managing finances, and managing medications. Other physical activities: includes walking, climbing stairs, crouching, stooping, kneeling, lifting, and getting up from a chair. MIDUS III: The next phase of the Midlife in the United States Study, MIDUS III, began data collection in 2013. Interviews about cognition will be conducted with 2,680 sample members (MIDUS, 2011e).

Abbreviations:

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; MIDUS I = Midlife in the United States, Baseline Study; MIDUS II = Midlife in the United States, Follow-up Study; NCHS = National Center for Health Statistics; NIA = National Institute on Aging; SSA = Social Security Administration.

SOURCES:

BRFSS items come from the 2014 questionnaire, BRFSS: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (CDC, 2013b).

The HRS items come from the 2014 questionnaire, HRS: Health and Retirement Study (HRS, 2014a, 2015).

MIDUS items come from the MIDUS I and II phone interview questionnaires and the self-administered questionnaires: MIDUS I (MIDUS, 2011b); MIDUS II (MIDUS, 2011c,d,e).

NHATS items come from the 2011, 2012, and 2013 questionnaires, NHATS: National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS, 2014a,d,e,f).

NHANES items come from the 2013/2014 questionnaire, NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (CDC, 2014b,c).

As shown in Table 3-1, the sample sizes for the five ongoing surveys and studies range from 5,000 participants annually for the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) up to about 500,000 for the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). NHANES includes people of all ages, while BRFSS and the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study include adults age 18 years and older and 24 years and older, respectively. The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) includes adults age 50 years and older, while the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) includes adults age 65 years and older. Four of the five surveys and studies shown in Table 3-1 measure respondents’ cognition directly, and all five include survey items to assess respondents’ awareness and perceptions about their cognition.

Like all nationally representative research, these surveys and studies have limitations in their breadth and depth of coverage. The five studies described in Table 3-1 cover numerous health and social topics, but none is dedicated solely to cognition. The breadth of topics they cover enhances their value for researching potential correlations between cognition and other factors of interest from a public health perspective. All five collect information about race and ethnicity, and four of the five collect information about veteran status. All five ask about medical conditions, such as hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and stroke, and other factors related to cognitive aging as discussed in Chapters 4A and 4B—for instance, physical activity and exercise, smoking, and social engagement. All five also ask about various functional activities that may be affected as part of cognitive aging. At the same time, the breadth of topics covered in the surveys and studies necessarily limits the depth of information specifically about cognitive aging. Moreover, nationally representative surveys and studies often have too few people with similar characteristics to assess regional or local variations with the precision needed to inform public health decisions or explore less common minority, nationality, or language groups. These more in-depth questions usually require targeted surveys or expanded samples or subsamples in national surveys.

A brief overview of the information available about cognitive aging from these existing surveys and studies is presented below. Information is provided about three aspects of cognitive aging: cognitive status at a point in time, cognitive changes that occur in individuals as they age, and older adults’ self-reported awareness and perceptions regarding these changes.

Although some researchers are familiar with the available information about cognitive aging from these and other surveys and studies, the information is generally not presented in formats, language, and media that are accessible to most older adults; to health care and financial professionals and others who work with older adults; to the staff of government and private-sector organizations that plan, implement, and evaluate public health

programs; and to other non-research audiences. If reformatted and stated in language that is meaningful to these audiences, this information could help to increase public awareness and understanding, answer questions and address concerns of older adults and their families, assist health care and financial professionals and others in educating and advising their older patients and clients, and guide program development and implementation.

Information About Cognitive Status at a Point in Time

Research that directly measures cognition can provide a snapshot of the cognitive status of individuals at a single point in time. Such snapshots reveal differences between people of different ages or who differ on other characteristics; such differences are often referred to as inter-individual differences. Three of the studies shown in Table 3-1—MIDUS, the HRS, and NHATS—have provided information about inter-individual differences in cognitive status.

Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) Study

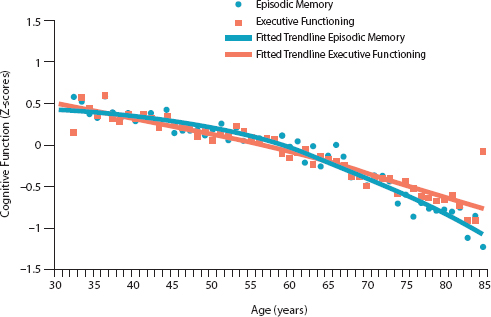

The MIDUS study examines a variety of factors that play a role in age-related variations in health and well-being (see Table 3-1; MIDUS, 2011a). The first phase of the study, MIDUS I, conducted from 1995 to 1996, assembled a sample of 7,108 individuals ages 24 to 75 years; cognition was measured directly in only a subsample of 302 individuals (Agrigoroaei and Lachman, 2011). The second phase of the study, MIDUS II, was conducted from 2004 to 2006, and cognition was measured in 4,268 of the original sample members, who were then ages 32 to 84 years (Lachman et al., 2014). Figure 3-1 shows the average scores for all MIDUS II sample members on tests of two components of cognition: episodic memory, including immediate and delayed recall, and executive functioning. The figure shows lower average scores on tests of episodic memory and executive function for individuals in each successive 5-year age group.

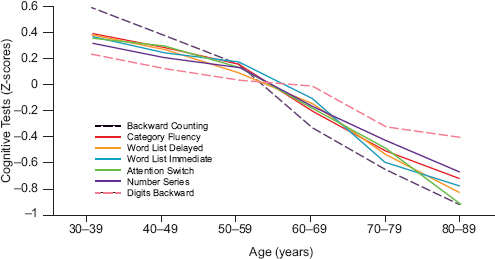

Figure 3-2, based on data from the MIDUS II study sample, shows a steady decline by age on each of the seven tests of various components of cognition (Lachman and Tun, 2008). The pattern differed somewhat from test to test, but the decline was steady in all. As in Figure 3-1, this figure reflects differences between individuals of different ages rather than changes in cognition in the same individuals over time.

Health and Retirement Study (HRS)

The HRS examines changes in many characteristics of adults age 50 years and older as they transition from work to retirement and older age

FIGURE 3-1 Differences in cognitive functioning by age, Midlife in the United States Study II (MIDUS II), N = 4,268, United States, 2004–2006.

NOTE: The use of Z-scores, shown on the vertical axis, enables data from different tests to be shown on the same scale. The dots represent the average scores of individuals by year of age. The solid lines are trend lines developed by statistical methods to show average trends in the data.

SOURCE: Lachman et al., 2014. Reprinted by permission of Sage Publications.

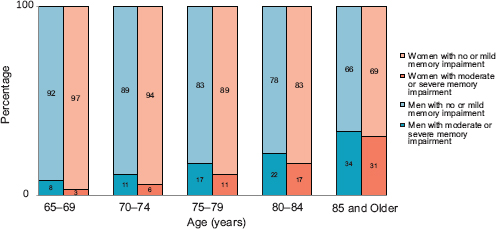

(see Table 3-1; HRS, 2014a). As discussed earlier, analyses of data from many existing surveys and studies often focus on moderate and severe cognitive impairment, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease rather than on the less severe cognitive changes that are the topic of this Institute of Medicine report. Figure 3-3 provides one example of findings from such an analysis, using data from the 2002 HRS. The figure shows the proportions of men and women age 65 years and older who had moderate or severe memory impairment according to tests that measured immediate and delayed recall as well as the much larger proportions of these men and women who had no memory impairment or only mild memory impairment. Sample members were considered to have had moderate memory impairment if they remembered four or fewer words out of 20 on immediate- and delayed-recall tests. They were counted as having severe memory impairment if they remembered two or fewer words on the tests.

The original graph from which Figure 3-3 was adapted appeared in Older Americans 2000: Key Indicators of Well-Being, a publicly available federal government report (FIFARS, 2004). That graph showed only the

FIGURE 3-2 Differences in cognitive functioning by age based on different cognitive tests, Midlife in the United States Study II (MIDUS II), N = 4,268, United States, 2004–2006.

NOTE: The use of Z-scores, shown on the vertical axis, allows data from different tests to be shown on the same scale.

SOURCE: Lachman and Tun, 2008, revised and reformatted; Lachman, 2014. Published with permission from Sage Publications.

FIGURE 3-3 Proportions of people age 65 and older with moderate or severe memory impairment versus no or mild memory impairment, Health and Retirement Study, United States, 2002.

SOURCE: Adapted from FIFARS, 2004.

lower parts of the bars, which represented the proportions of men and women who had moderate or severe memory impairment. The extension of the bars in Figure 3-3 is intended to call attention to the large numbers of men and women age 65 years and older who are left out when the analyses focus only on moderate or severe impairment—in this case, proportions ranging from 92 percent of men and 97 percent of women age 65 to 69 years to 66 percent of men and 69 percent of women age 85 years and older.

Figure 3-3 is informative with respect to the extent of moderate and severe memory impairment in the older population and the way that the proportion of older adults with these conditions increases with increasing age. Even with the extended bars, however, the figure provides no information about variations in memory within the large proportions of older adults who did not have moderate or severe memory impairment. Yet some—and perhaps many—of the people who are shown as having no memory impairment or only mild memory impairment are likely to have experienced changes in memory and other cognitive functions that concern them and affect their day-to-day activities.

The HRS findings on global cognition, including memory and other cognitive functions, are often reported in four categories: normal, plus three categories of cognitive impairment as defined for the particular study. Using these categories, data for the HRS study population in 2002 show that 3.5 percent of the subjects who were age 70 years and older had “mild cognitive impairment,” 5.2 percent had “moderate” or “severe cognitive impairment,” and 91.3 percent had “normal cognitive function” (Langa et al., 2008). As is true for Figure 3-3, these proportions are informative with respect to the extent of cognitive impairment in older adults and are encouraging in the sense that the great majority of older adults do not have cognitive impairment as measured by the tests and scoring procedures used for study. However, no information is provided about variations in cognition in the very large proportion of the sample categorized as having “normal cognitive function.”

National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS)

NHATS examines changes in the daily life and activities of adults of age 65 years and older (see Table 3-1; NHATS, 2014c). NHATS findings about cognition are often reported in three categories: probable dementia, possible dementia, and no dementia (Kasper et al., 2013). NHATS data for more than 7,600 sample members indicate that in 2011, 11.2 percent had probable dementia, and 10.6 percent had possible dementia, leaving 78.2 percent with no dementia (Kasper et al., 2014). Like the HRS figures, these NHATS figures are informative with respect to the extent of probable and possible dementia and encouraging in the sense that the great majority of

older adults do not have these conditions. Yet, as with the HRS data, the NHATS figures provide no information about variations in cognitive function among the majority of older adults categorized as having no dementia.

Challenges and Opportunities for Point-in-Time Data Collection and Analysis

In these surveys and studies, the focus on moderate and severe cognitive impairment and on probable and possible dementia undoubtedly reflects the high level of interest in dementia and dementia-related conditions among researchers, policy makers, and the public as well as the relatively lower level of interest to date in the less severe changes in cognition that are the focus of this report. People with less severe cognitive changes are variously categorized as having “normal cognitive function,” “mild cognitive impairment,” or “no dementia.” The implications of these terms and categories are unclear with respect to cognitive abilities, impairments, and needs for information and assistance among the large number of adults so categorized. Raw data from the HRS, NHATS, and other surveys and studies could be used to discriminate more finely between these individuals. As discussed later in this chapter, the challenge will be to create operational definitions of meaningful categories for analyzing the raw data and reporting survey findings. Establishing these definitions would allow further differentiation of cognitive functioning among the vast majority of elders and enable the development of needed, population-based information about cognitive aging.

A few studies and surveys have tested methods to identify older adults who have a high level of cognition even at very old ages, thus enabling the creation of a category of cognition that has been referred to as “successful cognitive aging,” a term this report does not use (see Chapter 1). One study tested several identification methods in a sample of 560 community-dwelling adults age 65 years and older (Negash et al., 2011). One method classified “successful agers” as those individuals with scores above the sample average on tests of four components of cognition. A second method compared the sample members’ scores on tests of four components of cognition with the scores of adults ages 24 to 35 years and identified as “successful agers” the older adults who had scores at a specified level above the average for the younger adults. Both of these methods identified more sample members as “successful agers” than did a third method, which identified older adults with scores in the top 10 percent on a composite measure of the four components. Each of these methods could be used to create useful new categories of cognition within the current undifferentiated categories “normal cognitive function” and “no dementia.” The three methods identified some of the same individuals, but many individuals were identified by only one or two of the methods, illustrating the difficulties

facing those who aim to create meaningful categories for analyzing and reporting survey findings about cognition.

Information About Changes in Cognition Over Time

Many surveys that directly measure sample members’ cognition are longitudinal; that is, they interview the same individuals more than once—and often numerous times—over a period of years. About three-quarters of the 40 U.S. surveys and studies identified by Bell and colleagues (2014) and 3 of the 5 surveys and studies included in Table 3-1 are longitudinal. Data from these studies could be used to describe changes in cognition for individuals over time. Depending on the cognitive functions measured in each survey, information could be provided about changes in global cognitive function as well as about particular components of cognition, such as memory, orientation, executive function, vocabulary, and reasoning. Information also could be gleaned about rates of change in cognitive performance, including the proportions of individuals whose cognition improves, stays the same, or declines over time.

As discussed in Chapters 1 and 2, the patterns and trajectories of cognitive change in individuals over time are extremely varied. Figure 2-1 in Chapter 2 shows data from the HRS on changes in cognitive scores over time in a representative sample of adults who had taken the cognitive tests in two or more waves of the study (McArdle, 2011). The figure illustrates the extensive variation among older adults in their patterns and trajectories of cognitive aging. It also shows the substantial variation between sample members at each age, something that is difficult to appreciate when only the average scores are presented. Furthermore, it shows that even though the average scores declined steadily over time, the scores for some individuals improved or at least stayed the same from one test time to a later one.

Other longitudinal studies conducted in representative samples of regional and local populations and in non-representative community samples have reported the proportions of older adults whose cognition stayed the same or declined over various time periods. All of these studies started with samples of individuals who were functioning at a relatively high level. A study of 2,733 generally healthy men and women ages 70 to 79 years found that after 4 years, 36 percent of the sample members had maintained the same level of cognitive functioning, 48 percent had experienced a minor decline in cognitive functioning, and 16 percent had had a major decline (Yaffe et al., 2010). Among the 2,509 sample members who were still participating in the study after 8 years, cumulative results show that 30 percent had maintained their level of cognitive functioning, 53 percent had a minor decline, and 16 percent had a major decline (Yaffe et al., 2009).

As could be expected, studies that lasted longer found lower propor-

tions of sample members whose cognition had stayed the same over the study period. A 15-year study of 9,704 women age 65 years and older found that 9 percent maintained the same level of cognition functioning until the end of the study, 58 percent had a minor decline, and 33 percent had a major decline (Barnes et al., 2007). Similarly, a 9-year study of 322 women ages 70 to 80 years found that 49 percent had declined to predesignated levels of impairment in one or more components of cognition by the end of the study, with 37 percent having declined in executive function, 28 percent in immediate recall, 26 percent in delayed recall, and 21 percent in psychomotor speed (Carlson et al., 2009).

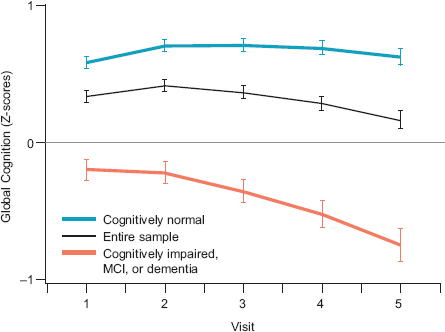

As part of the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, which is conducted in a representative sample of a regional population, researchers measured changes over time in the cognitive trajectories of 1,390 adults ages 71 to 89 years (Machulda et al., 2013). All of the sample members were classified as cognitively unimpaired at the beginning of the study. Figure 3-4 shows the changes in the cognitive trajectories for global cognition in those sample members who were tested at least twice (and up to five times) over the course of the 5-year study. Of the 1,390 sample members, 947 (68 percent) remained cognitively unimpaired, 397 (29 percent) developed diagnosable mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and 46 (3 percent) developed dementia. Trajectories for sample members who developed MCI or dementia started out lower and had a somewhat steeper rate of decline when compared either with all sample members or with those who remained cognitively unimpaired. The researchers called attention to the fact that both the entire sample and the cognitively unimpaired sample—but not the sample that developed MCI or dementia—showed improvements in scores of cognition between the first and the second visits. They attribute the improvements to practice effects and note that all three groups showed improvements in scores on memory between the first and second visits (Machulda et al., 2013). (For further discussion about practice effects, see Chapter 2 and Thorgusen and Suchy, 2014.)

Self-Reported Awareness and Perceptions About Changes in Cognition

Surveys and studies that measure individuals’ awareness and perceptions about their cognition can provide insight into older adults’ thinking about changes in their own cognition and into how those changes affect their functioning. Each of the five nationally representative surveys and studies described in Table 3-1 includes one or more questions designed to measure respondents’ awareness and perceptions of change in their cognition. At least four other ongoing surveys and studies conducted in nation-

FIGURE 3-4 Cognitive trajectories for global cognition in older adults, Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, N = 1,390.

NOTE: MCI = mild cognitive impairment. The middle (black) line represents changes in cognitive trajectories for the sample as a whole. The lower (orange) line represents changes in trajectories for individuals who developed MCI or dementia during the study, and the top (blue) line represents changes in trajectories for individuals who remained cognitively unimpaired at the end of the study.

SOURCE: Machulda et al., 2013. Reprinted with permission of Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

ally representative samples also include one or more such questions2 as do many regional and local surveys and studies. These surveys and studies use terms, such as “thinking,” “remembering,” “forgetting,” “confusion,” “memory loss,” and “serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions,” to refer to cognition in their questions.

BRFSS conducts annual surveys to collect information about personal health behaviors and risk factors for mortality and morbidity (see Table 3-1; CDC, 2013a). BRFSS surveys are conducted by individual states, with administrative support and funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The surveys include three types of questions: core questions, optional modules, and state-added questions. States are required to use the core questions in their state BRFSS surveys, but they can choose

____________

2American Community Survey, Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, Medicare Expenditure Panel Survey, and National Health Interview Survey.

whether to use any of the optional modules and whether to add questions of their own. In 2007, the CDC’s Healthy Aging Program developed a set of 10 questions, referred to as the Optional Impact of Cognitive Impairment Module (CDC, 2007), to collect information about survey respondents’ awareness and perceptions about their cognition (CDC, 2014a). The CDC and the Alzheimer’s Association encouraged states to use this optional module and provided financial support for its use and for analysis of the resulting data.

Findings from 21 states that used the 2007 optional module in their 2011 BRFSS surveys show that among adult respondents age 60 years and older, 12 percent reported increased confusion or memory loss in the preceding 12 months, and that in that group more than a third also reported increased functional difficulties. The proportion of respondents reporting increased confusion or memory loss was higher among respondents who were 85 years or older, who were Hispanic, who had less than a high school education, or who reported that they were disabled (CDC, 2013c).

In 2014, the CDC and the states developed a new six-item optional module, the 2015 Cognitive Decline Module, to replace the 2007 module. As shown in Box 3-2, the new model asks respondents whether they have noticed changes in their cognition in the previous year and whether any such changes have affected their day-to-day functioning or resulted in the need for help with these activities. Some states are including the new module in their 2015 BRFSS survey, and it is hoped that many states will eventually do so.

Over at least the past four decades, questions have been raised about the validity of self-reported information about cognition. Research conducted in the United States and other countries has attempted to determine whether individuals’ reports of cognitive decline, usually referred to as “subjective memory complaints,” reflect true decline or other factors. Many studies have found subjective memory complaints to be associated with depression, other psychological distress, and personality characteristics such as conscientiousness, self-esteem, and neuroticism (Blazer et al., 1997; Kahn et al., 1975; O’Connor et al., 1990; Pearman and Storandt, 2004). Some researchers have concluded that these factors are the main driver of subjective memory complaints (see, e.g., Pearman and Storandt, 2004). Others have been persuaded that subjective memory complaints indicate real cognitive impairment and may also predict future cognitive decline (see, e.g., Geerlings et al., 1999; Jonker et al., 1996, 2000).

Research on the association between subjective memory complaints and current and future cognitive status as measured with objective tests has resulted in complex and sometimes contradictory findings. Among studies that have measured the association between subjective memory complaints and current cognitive status, those studies conducted in community samples

BOX 3-2

Introduction and Questions in the 2015

BRFSS Cognitive Decline Module

Interviewer Introduction: The next few questions ask about difficulties in thinking or remembering that can make a big difference in everyday activities. This does not refer to occasionally forgetting your keys or the name of someone you recently met, which is normal. This refers to confusion or memory loss that is happening more often or getting worse, such as forgetting how to do things you’ve always done or forgetting things that you would normally know. We want to know how these difficulties impact you.

- During the past 12 months, have you experienced confusion or memory loss that is happening more often or is getting worse?

- During the past 12 months, as a result of confusion or memory loss, how often have you given up day-to-day household activities or chores you used to do, such as cooking, cleaning, taking medications, driving, or paying bills?

- As a result of confusion or memory loss, how often do you need assistance with these day-to-day activities?

- When you need help with these day-to-day activities, how often are you able to get the help that you need?

- During the past 12 months, how often has confusion or memory loss interfered with your ability to work, volunteer, or engage in social activities outside the home?

- Have you or anyone else discussed your confusion or memory loss with a health care professional?

SOURCE: CDC, 2014a.

have often found a stronger association than those conducted in clinical samples (Jonker et al., 2000). Studies that include individuals with various levels of cognitive impairment have generally found a stronger association between subjective memory complaints and current cognitive status in individuals with no or very mild cognitive impairment than in individuals with more cognitive impairment (Lerner et al., 2015; Turvey et al., 2000). Similarly, studies that include individuals with depressive symptoms have generally found a stronger association between subjective memory complaints and current cognitive status in individuals with fewer depressive symptoms than in individuals with more depressive symptoms (Hohman et al., 2011; Jungwirth et al., 2004). One analysis of data from a nationally representative community sample of 5,444 individuals age 70 years and older found a substantial association between individuals’ reports about their own cognition and their scores on objective tests of cognition (Turvey et al., 2000). The association was weaker, however, for sample members

whose cognitive test scores were in the lowest quarter of test scores, 57 percent of whom reported their memory was good, very good, or excellent. Likewise, the association was weaker for sample members with depressive symptoms.

Age, level of education, and other socio-demographic factors have also been found to affect the association between subjective memory complaints and current cognitive status in older adults. For example, three studies found substantial associations between subjective memory complaints and scores on objective tests of cognition in the young-old sample members (individuals under ages 75 or 80 in the study samples) but not in the older-old sample members (Fritsch et al., 2014; Hohman et al., 2011; Lerner et al., 2015).

Associations between subjective memory complaints and scores on objective tests of cognition may also depend on the specific complaints, the number of complaints, and the components of cognition measured (Amariglio et al., 2011; Riedel-Heller et al., 1999). An analysis of data from a large—but not population-based—study of almost 17,000 women of ages 70 to 81 years found that some subjective memory complaints, such as difficulty finding one’s way around familiar streets, were more highly associated than other complaints with scores on objective tests of cognition (Amariglio et al., 2011). The complaint of forgetting things from one second to the next was not associated with cognitive status, but sample members who had many subjective memory complaints were more likely to score low on the cognitive test than those with fewer complaints.

Older adults’ awareness and perceptions about changes in their own cognition are important because awareness and perceptions can affect the likelihood that they will hear and respond to messages about lifestyle and other factors that could improve their cognitive health and reduce the negative effects of cognitive aging. Gaining an increased understanding about the variations among older adults in their awareness and perceptions about changes in their own cognition could help health care and financial professionals and others who work with older adults individualize the education and advice that they provide to their patients and clients. Similarly, population-based information about older adults’ awareness and perceptions about changes in their cognition could help public- and private-sector agencies at the national, state, and local levels develop and deliver messages and programs that match the array of perceptions about cognitive aging in the populations they serve.

Furthermore, the results of recent longitudinal studies generally support earlier findings of associations between subjective memory complaints and future cognitive decline (Glodzik-Sobanska et al., 2007; Kryscio et al., 2014; Reid and MacLullich, 2006; Reisberg et al., 2010; Slavin et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2004). These studies are generally conducted with samples

of people who do not show any cognitive impairment on objective tests, suggesting that subjective memory complaints may represent very early awareness of changes in cognition that are too subtle to detect with objective cognitive tests (Petersen, 2014).

Given the complexity of findings about the association of subjective memory complaints and current cognitive status based on objective cognitive tests, and given the still early stage of research on the association of subjective memory complaints and future cognitive impairment, caution is needed in the dissemination of findings from population-based surveys and studies that measure self-reported changes in cognition, such as BRFSS. Reported findings must clearly discriminate between self-reported findings and those findings that are based on objective cognitive tests. Reported findings must also avoid language implying that findings based on self-report represent respondents’ cognitive status as measured with objective tests. In this context, it is also important to acknowledge that some—and perhaps many—people may be aware of changes in their own cognition but are not willing to report their awareness on a survey for various reasons, including stigma. As discussed in Chapter 2, age, ethnicity, culture, level of education, and other factors associated with familiarity and comfort in testing situations can affect responses to research questions. Thus, reviews of findings from surveys and studies that measure self-reported cognitive status and cognitive changes in older adults’ awareness and perceptions about changes in cognition must acknowledge the many factors that could lead to underreporting.

CHALLENGES TO INCREASING POPULATION-BASED INFORMATION ABOUT COGNITIVE AGING

At least five important challenges will have to be addressed in creating a system that will effectively collect, analyze, and disseminate population-based information about cognitive aging, particularly for public health purposes. These challenges are the development of (1) operational definitions of cognitive aging; (2) standards and procedures for ensuring representative, population-based samples; (3) cognitive tests and survey questions relevant for cognitive aging; (4) efficient modes of testing that maximize respondent participation and the accuracy of findings; and (5) methods for the appropriate use of proxy respondents and the incorporation of proxy responses into the available information about cognitive aging.

Although the availability of improved population-based information about cognitive aging is likely to be useful for research and public policy purposes, the primary objectives in creating a system to collect, analyze, and disseminate this information are to:

- increase public awareness and understanding about cognitive aging;

- engage individuals and their families in maintaining cognitive health across the life span;

- inform health care professionals, financial professionals, and others in how to educate and advise their older patients about cognitive aging; and

- guide the planning, implementation, and evaluation of programs and initiatives to maintain cognitive health and reduce the negative effects of cognitive aging for older adults, their families, and their communities.

Developing Operational Definitions of Cognitive Aging

While many population-based surveys and studies collect or use data on cognition in older persons (Bell et al., 2014), relatively little attention has been given to developing operational definitions that would allow for population-based estimates of the nature and extent of cognitive aging. As described in this chapter, findings about cognition from nationally representative surveys and studies, such as the HRS and NHATS, are often reported in categories that emphasize moderate and severe cognitive impairment and dementia. These categories reflect the current high level of interest in dementia and dementia-related conditions among researchers, policy makers, and the public, but they leave out the kinds of cognitive changes that are experienced by the majority of older adults—changes that are troubling to many older adults and that may affect important day-to-day functions, such as driving, making financial decisions, and managing medications.

Developing operational definitions of cognitive aging is challenging because aging is an ongoing process with wide variation among individuals. As discussed in Chapter 2, the current understanding about the boundaries between the various levels of cognition in older adults is incomplete. Uncertainty about these boundaries and the current lack of agreed-upon standards or norms that could be used to translate individuals’ raw scores on cognitive tests into meaningful categories are major barriers to the development of a system of population-based surveillance. It remains to be determined whether acceptable boundaries and thresholds can be identified.

The comprehensive characterization of cognitive aging used by the committee in this report (see Chapter 1) has not yet been translated into explicit operational definitions and criteria that could be applied in surveys and studies conducted in population-based, volunteer, or clinical samples. The current lack of standardized and explicit diagnostic and categorization criteria impedes the conduct and interpretation of epidemiologic studies. Comprehensive population-based surveys and studies require operational definitions in order to compare findings across studies and population seg-

ments and to determine any time trends. Once consensus definitions are developed, it will be important to determine the optimal interval between surveys in a study cohort for determining rates of cognitive aging over time.

Operational definitions of cognitive aging will require, among other considerations, a standardized set of cognitive scales and tests. Many population studies use similar cognitive items and tap similar cognitive domains (such as memory, executive function, and orientation), but variations in item and scale origin and structure may make comparisons among them difficult.

Newer test development initiatives based on modern test theory aim to increase the standardization of cognitive testing across studies, improve the reliability and validity of cognitive tests, and increase the efficiency in the number of test items. Item response theory, for example, has been used in the development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) self-report cognitive function scales (Cella et al., 2010) and the NIH Toolbox Assessment of Neurological and Behavioral Function®. Item response modeling is designed to measure the underlying traits that are producing performance on a test (Wilson et al., 2006a,b) and has the practical advantages of allowing the aggregation of items measuring common constructs and also allowing item banking for computer adaptive testing targeted to the individual (Becker et al., 2014; Gershon et al., 2014). Both the PROMIS cognitive scales and the NIH Toolbox® cognitive battery were originally designed to meet research needs, but they may also be useful in developing operational definitions and criteria for population-based surveillance.

Ensuring the Representativeness of Population-Based Samples

Another important challenge in conducting population-based research on cognitive aging is that the sampling frame may not represent the population. In general, participation rates for national and regional surveys have been declining (Galea and Tracy, 2007). It is quite plausible that people having different levels of cognitive function may differ in their likelihood of participating in such surveys, and some individuals, because of illness or a refusal to participate, may not be testable even in special clinical settings. The impact of such selective non-participation can be understood if important characteristics of the sampling frame sources are available, such as from a Medicare beneficiary sample, but this information is frequently not easily accessible. Significant levels of survey non-response can lead to uncertainty and potential bias in survey findings.

Among the most important demographic characteristics in population surveys are race and ethnicity. Racial disparities in late-life cognitive performance are well documented (see, e.g., Sisco et al., 2014). While some of

these disparities can be statistically explained by variation in individual or family socioeconomic status (SES) or disadvantages in the childhood social environment (Cheng et al., 2014), there may be important differences between how SES correlates with cognitive status and how it correlates with the changes in cognitive status over time (Yaffe et al., 2009; Zahodne et al., 2011). Furthermore, other factors—for example, test bias and reading levels—may account for part of the variation among racial groups, particularly between whites and African Americans (see, e.g., Fyffe et al., 2011; Mehta et al., 2004). These factors are often not well studied, particularly with respect to adjusting findings for racial and ethnic variation. More work is needed when planning and executing research to assess cognitive aging across population groups known to have systematic variation in cognitive performance.

Each of the five surveys and studies in Table 3-1 includes questions about race and ethnicity. As noted earlier, however, nationally representative surveys and studies often have an insufficient sample size to explore less common minority, nationality, or language groups with the precision needed to affect public health decisions; understanding these groups in any detail usually requires separately targeted surveys or expanded samples or subsamples.

Other important issues affecting the representativeness of population-based surveys and studies pertain to the inclusion of individuals with serious co-morbid medical or mental health conditions and individuals living in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. These individuals are more likely to have higher-than-average levels of cognitive impairment. Even those who do not have diagnosable MCI or dementia are likely to have age-related cognitive changes that affect their day-to-day functioning.

Including Relevant Cognitive Tests and Survey Questions About Cognition

As noted earlier, cognitive test results vary, depending on the specific test used. This is important because the cognitive tests used in existing population-based surveys and studies vary widely, in part because of the amount of time they allocate for cognitive assessment. Furthermore, many of the cognitive tests used in national surveys are oriented to assessing or at least screening for major dementia-related conditions, using validated mental status scales and instruments. Some of these instruments lack the ability to detect and evaluate variations at the higher end of cognitive performance, and additional, more sensitive instruments to measure cognition in the high functioning range may be needed. Still, within surveys and studies that address cognitive aging, the ability to identify MCI and dementia

is important so that those individuals can be excluded from the analysis of cognitive aging, as characterized in Chapter 1.

Additional test-related issues include identifying the best measures of change in cognition and determining the time intervals that are most appropriate for monitoring change. Questions about cognition must be as comprehensible as possible across a broad range of literacy levels, and responses may need to be interpreted differently for people who have different primary languages or racial and ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, the contribution of practice effects, when individuals are given the same tests or test items on two or more different occasions, need clarification.

As noted in Chapters 1 and 2, any definition of cognitive aging must consider the functional impact of such aging on individuals and on the people in their social environment. However, much more research is needed to identify the physical, mental, and social functions that may be affected by cognitive aging, and these alterations may differ substantially among individuals for any number of reasons. Existing population-based surveys and studies include questions about activities of daily living (such as bathing and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and several IADLs—notably money and medication management—have been described as “cognitive IADLs.” It is also important to capture, to the extent possible, how cognitive changes affect other complex tasks with practical relevance, such as tasks that take place within work, family, or other social environments (Czaja and Sharit, 2003). The BRFSS Cognitive Decline module (CDC, 2014a) includes questions about the areas in which a person needs the most help, such as whether the person’s confusion or memory loss has interfered with his or her ability to work, volunteer, or engage in social activities. Likewise, the HRS and NHATS include questions that link cognitive decline with problems with various activities such as “being able to work familiar machines,” “learning to use a new tool, appliance, or gadget,” and “being able to follow a story in a book or on TV” (HRS, 2014b; NHATS, 2014b).

Selecting Efficient Modes of Testing

It is important to select efficient modes of testing that maximize respondent participation and the accuracy of findings. Existing surveys and studies of cognition generally rely on in-person and telephone interviews, and some of them use printed or online self-assessments completed by the respondent at home. Newer modes of online testing are also being used. The choice of survey modes will be dictated at least in part by cost considerations. In-person interviews, which are the most costly mode of testing, can allow the self-report of cognitive symptoms, consequent dysfunction,

the use of self- or family-directed remedies, relevant co-morbidity, and the use and outcomes of consultation in formal medical care. Such information is critical and would be difficult to collect for individuals, family caregivers, and other family members in any other way.

Using Proxy Respondents and Responses

Many existing population-based surveys and studies that measure cognition include questions that are asked of proxy respondents, who are usually family members and other informants, in addition to or instead of those questions for the older adults themselves. In some surveys, the proxy respondent answers questions only if the sample person is not able to, while in other surveys both the proxy respondent and the sample person answer the questions.

Population-based surveillance of cognitive aging might profitably include proxy respondents as a matter of routine whenever they are available. They may provide different and more detailed information than the index respondent. It is unclear, however, to what extent proxy respondents are needed in the case of respondents with cognitive changes that do not reach the level of MCI or dementia. It is also likely that there will be differences in the responses given by the older adult, by a family member, or by other proxy respondents. These differences have been studied for many years among people with dementia but have received less attention with respect to people with less severe cognitive change.

NEXT STEPS AND RECOMMENDATION

As noted in this chapter, a substantial amount of community and population research has been conducted on cognitive performance among older persons. The problem of cognitive aging, which is increasing in public health importance, underscores the need for a more robust surveillance system. While much of the research on representative geographic samples has focused on the detection and assessment of moderate and severe dementia-related conditions, investigative and public interest in cognitive aging is also rapidly increasing. Studies on volunteer research populations have provided important scientific findings, but from a public health perspective, a more complete view is needed of the nature and extent of cognitive aging in older adults. The committee concludes, therefore, that a more extensive surveillance approach is warranted, which will require careful planning and pretesting. The committee offers the following vision for the next steps for such a program.

Build on Current Surveys and Related Data Sources

Because of both the costs and the complexity of surveillance for cognitive aging, it may be useful to share resources and questionnaire space with other ongoing national surveys and studies. Many relevant items are already in place, and collaborations with existing surveys should prove worthwhile. Surveys conducted with representative samples of regional and local populations can also contribute to the understanding of cognitive aging.

Some of the categories used to report information about cognition in surveys and studies conducted with representative regional and local population samples are the same from survey to survey, and some vary. Some surveys (e.g., the HRS and NHATS) use categories that reflect a strong emphasis on dementia and predementia conditions. Other regional and local research obtains detailed information about cognition as an outcome, a control variable, or a predictor of other study outcomes (McArdle et al., 2007). This detailed information is rarely reported, however. Instead, it is often converted to statistics, which are essential for research but which cannot be used to increase understanding of cognitive aging in non-research audiences.

Perhaps the most important question remaining is whether existing population data accurately characterize, in terms of the prevalence and incidence of cognitive aging, the overall cognitive status of a community or nation. Accepting existing cognitive measures as indicators of age-related changes would enable the development of score thresholds and ancillary rules or algorithms to define population rates. However, as discussed earlier, providing community-wide information about cognitive aging rates requires more research as well as the specification of well-considered operational definitions of cognitive aging. Only then could even provisional rates of population cognitive aging rates be estimated. Additional logistical and practical questions, include

- How inclusive does a population sample have to be? How can adequate representation of racial, ethnic, and non-English-speaking minority individuals be assured? Should those who may be cognitively impaired and residing in institutional settings be included? How would incomplete participation rates, as well as information from proxy respondents, be handled?

- What battery of cognitive tests should be included? How should co-existing cognitive conditions such as MCI or Alzheimer’s disease be excluded, and by what means would dementia-related illnesses be determined?

- How would the test battery be standardized? Would this be based on statistical distributions, such as percentiles? How would a composite cognitive index be constructed? Would there be adjustment for educational attainment or other factors known to alter cognitive performance? Would designation of cognitive aging require evidence of physical or social dysfunction?

- How would self-reported cognitive symptoms be integrated with cognitive test scores?

- What modes of testing would be acceptable, and would mixed modes be credible?

- How would individuals with serious co-morbid medical or mental conditions be surveyed and counted?

Expand the Types of Data Collected and Examine Other Approaches to Data Collection

Ongoing or periodic surveillance for cognitive aging may include data collection from sources other than personal interviews and test results. For example, analyses of de-identified data from large health systems’ electronic health records may provide useful information in many cognitive and related clinical domains, as is occurring in other areas of surveillance. Sales data for drugs or other products used for the prevention or management of cognitive impairment may provide useful insights into population and professional concerns. Similarly, it may be useful to monitor secondary effects of cognitive aging from public records, such as police reports of persons getting lost and automobile crash rates among older persons. Financial transactions, such as mispaid bills, aberrant fund transfers, and unsuitable transactions, are another ecologically valid means of surveillance at both the individual and the population level, although confidentiality and privacy concerns would need to be addressed.

Disseminating Information to Survey Participants

Whatever the established protocols for routine surveillance programs, the emotional sensitivity of finding evidence for any level of clinical impairment during a cognitive assessment may raise the issue of whether test results should be returned to the surveillance participants for possible medical consultation. Individuals have different views on the desirability of receiving this information (Dawson et al., 2006), and providing cognitive test results without a clinical interpretation should be done cautiously, particularly when the results label a person as cognitively impaired. A sensible response to requests for results would be to also provide participants with information about how to discuss cognitive concerns with their health care provider.

Widely Disseminate Information to the General Public

As discussed in this chapter, existing U.S. surveys and other studies collect substantial amounts of information about cognition in older adults. Although some researchers are familiar with the available information about cognition, it is generally not presented in formats and media that are accessible to most older adults, health care professionals and others who work with older adults, administrative and program staff of government and private-sector organizations, and other non-research audiences. To make the information understandable and meaningful to these audiences will require significant reformatting and clear explanations of complex concepts. Terms will have to be defined in lay language, and methodological practices, such as the use of Z-scores to standardize results from different cognitive tests, will have to be explained or replaced. One of the biggest challenges in communicating meaningful and useful information about cognitive aging to the general public will be providing easy-to-understand explanations about the relationship between changes in cognition that older adults may experience and their risk of developing MCI or dementia, a relationship that is still not well understood. Increased understanding about cognitive aging could help increase public awareness, answer questions and address concerns of older adults and their families, improve the information advice health care and financial professionals and others provide to their older patients and clients, and help public health agencies and other public and private organizations create effective programs to reduce cognitive impairment and improve cognitive health in older adults.

RECOMMENDATION

Recommendation 2: Collect and Disseminate Population-Based Data on Cognitive Aging

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), state health agencies, and other relevant government agencies, as well as nonprofit organizations, research foundations, and academic research institutions, should strengthen efforts to collect and disseminate population-based data on cognitive aging. These efforts should identify the nature and extent of cognitive aging throughout the population, including high-risk and underserved populations, with the goal of informing the general public and improving relevant policies, programs and services.

Specifically, expanded cognitive aging data collection and dissemination efforts should include

- A focus on the cognitive health of older adults as separate from dementia or other clinical neurodegenerative diseases.

- The development of operational definitions of cognitive aging for use in research and public health surveillance and also the development of a process for periodic reexamination. Analyses of existing longitudinal datasets of older persons should be used to inform these efforts.

- Expanded data collection efforts and further analyses of representative surveys involving geographically diverse and high-risk populations. These efforts should include cognitive testing when standardized, feasible, and clinically credible and also self-reports of perceptions or concerns regarding cognitive aging, personal and social adaptations, and self-care and other management practices.

- Longitudinal assessments of changes in cognitive performance and risk behaviors in diverse populations.

- Inclusion of cognition-related questions in the core instrument of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, rather than an optional module.

- Exploration of other available relevant data on cognitive health such as health insurance claims data, sales and marketing data for cognition-related products and treatments, data on financial and banking transactions as well as on financial fraud and scams, and data on automobile insurance claims.

- Active dissemination of data on cognitive aging in the population. An annual or biennial report to the U.S. public should be issued by the CDC or other federal agency on the nature and extent of cognitive aging in the U.S. population.

REFERENCES

Agrigoroaei, S., and M. E. Lachman. 2011. Cognitive functioning in midlife and old age: Combined effects of psychosocial and behavioral factors. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 66B(S1):i130-i140.

Amariglio, R. E., M. K. Townsend, F. Grodstein, R. A. Sperling, and D. M. Rentz. 2011. Specific subjective memory complaints in older persons may indicate poor cognitive function. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 59:1612-1617.

Barnes, D. E., J. A. Cauley, L. Y. Lui, H. A. Fink, C. McCulloch, K. L. Stone, and K. Yaffe. 2007. Women who maintain optimal cognitive function into old age. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 55(2):259-264.

Becker, H., A. Stuifbergen, H. Lee, and V. Kullberg. 2014. Reliability and validity of PROMIS cognitive abilities and cognitive concerns scales among people with multiple sclerosis. International Journal of MS Care 16(1):1-8.

Bell, J. F., A. L. Fitzpatrick, C. Copeland, G. Chi, L. Steinman, R. L. Whitney, D. C. Atkins, L. L. Bryant, F. Grodstein, E. Larson, R. Logsdon, and M. Snowden. 2014. Existing data sets to support studies of dementia or significant cognitive impairment and comorbid chronic conditions. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (September 4).

Blazer, D. G., J. C. Hays, G. G. Fillenbaum, and D. T. Gold. 1997. Memory complaint as a predictor of cognitive decline: A comparison of African American and White elders. Journal of Aging and Health 9(2):171-184.

Brookmeyer, R., D. A. Evans, L. Hebert, K. M. Langa, S. G. Heeringa, B. L. Plassman, and W. A. Kukull. 2011. National estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 7(1):61-73.

Carlson, M. C., Q. L. Xue, J. Zhou, and L. P. Fried. 2009. Executive decline and dysfunction precedes declines in memory: The Women’s Health and Aging Study II. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 64A(1):110-117.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2007. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Optional Impact of Cognitive Impairment Module. http://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/impact_of_cognitive_impairment_module.pdf (accessed February 26, 2015).

———. 2013a. BRFSS: About BRFSS. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/about/index.htm (accessed December 19, 2014).

———. 2013b. 2014 Behavioral risk factor surveillance system questionnaire. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2014_BRFSS.pdf (accessed January 12, 2015).

———. 2013c. Self-reported increased confusion or memory loss and associated functional difficulties among adults aged ≥ 60 years—21 states, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62(18):347-350.

———. 2014a. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2015 Cognitive Decline Module. http://www.cdc.gov/aging/healthybrain/brfss-faq.htm (accessed December 19, 2014).

———. 2014b. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm (accessed December 19, 2014).

———. 2014c. NHANES 2013–2014. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/nhanes13_14.aspx (accessed January 12, 2015).

Cella, D., W. Riley, A. Stone, N. Rothrock, B. Reeve, S. Yount, D. Amtmann, R. Bode, D. Buysse, S. Choi, K. Cook, R. Devellis, D. DeWalt, J. F. Fries, R. Gershon, E. A. Hahn, J. S. Lai, P. Pilkonis, D. Revicki, M. Rose, K. Weinfurt, and R. Hays, and PROMIS Cooperative Group. 2010. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 63(11):1179-1194.

Cheng, E. R., H. Park, S. A. Robert, M. Palta, and W. P. Witt. 2014. Impact of county disadvantage on behavior problems among U.S. children with cognitive delay. American Journal of Public Health 104(11):2114-2121.

Cornoni-Huntley, J., D. B. Brock, A. Ostfeld, J. O. Taylor, R. B. Wallace, and M. E. Lafferty. 1986. Established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly: Resource data book. Vol. I. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging.

Cornoni-Huntley, J., D. G. Blazer, M. E. Lafferty, D. F. Everett, D. B. Brock, and M. E. Farmer. 1990. Established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Vol. II. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging.

Czaja, S. J., and J. Sharit. 2003. Practically relevant research: Capturing real world tasks, environments, and outcomes. Gerontologist 43(Suppl. 1):9-18.

Dawson, E., K. Savitsky, and D. Dunning. 2006. “Don’t tell me, I don’t want to know”: Understanding people’s reluctance to obtain medical diagnostic information. Journal of Applied Psychology 36(3):751-768.

FIFARS (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics). 2004. Indicator 17: Memory impairment. http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2004_Documents/healthstatus.aspx#Indicator17 (accessed December 19, 2014).

Fritsch, T., M. J. McClendon, M. S. Wallendal, T. F. Hude, and J. D. Larsen. 2014. Prevalence and cognitive bases of subjective memory complaints in older adults: Evidence from a community sample. Journal of Neurodegenerative Diseases. http://www.hindawi.com/journals/jnd/2014/176843 (accessed March 23, 2015).

Fyffe, D. C., S. Mukherjee, L. L. Barnes, J. J. Manly, D. A. Bennett, and P. K. Crane. 2011. Explaining differences in episodic memory performance among older African Americans and Whites: The roles of factors related to cognitive reserve and test bias. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 17(4):625-638.

Galea, S., and M. Tracy. 2007. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Annals of Epidemiology 17(9):643-653.

Geerlings, M. I., C. Jonker, L. M. Bouter, H. J. Ader, and B. Schmand. 1999. Association between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer’s disease in elderly people with normal baseline cognition. American Journal of Psychiatry 156(4):531-537.

Gershon, R. C., K. F. Cook, D. Mungas, J. J. Manly, J. Slotkin, J. L. Beaumont, and S. Weintraub. 2014. Language measures of the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery. Journal of the International Neuropsychology Society 20(6):642-651.

Glodzik-Sobanska, L., B. Reisberg, S. De Santi, J. S. Babb, E. Pirraglia, K. E. Rich, M. Brys, and M. J. de Leon. 2007. Subjective memory complaints: Presence, severity and future outcome in normal older subjects. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 24(3):177-184.

Hebert, L. E., J. Weuve, P. A. Scherr, and D. A. Evans. 2013. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology 80:1778-1783.

Hofer, S. M., and S. Clouston. 2014. Commentary: On the importance of early life cognitive abilities in shaping later life outcomes. Research in Human Development 11(3):241-246.

Hohman, T. J., L. L. Beason-Held, and S. M. Resnick. 2011. Cognitive complaints, depressive symptoms, and cognitive impairment: Are they related? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 59(10):1908-1912.

HRS (Health and Retirement Study). 2014a. Health and Retirement Study: A longitudinal study of health, retirement, and aging. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu (accessed December 18, 2014).

———. 2014b. HRS 2014—Section D: Cognition. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/2014/core/qnaire/online/04hr14D.pdf (accessed December 19, 2014).

———. 2015. Biennial interview questionnaires. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/index.php?p=qnaires (accessed January 12, 2015).

Jonker, C., L. J. Launer, C. Hooijer, and J. Lindeboom. 1996. Memory complaints and memory impairment in older individuals. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 44(1):44-49.

Jonker, C., M. I. Geerlings, and B. Schmand. 2000. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 15:983-991.

Jungwirth, S., P. Fischer, S. Weissgram, W. Kirchmeyr, P. Bauer, and K. H. Tragl. 2004. Subjective memory complaints and objective memory impairment in the Vienna–Transdanube aging community. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52(2):263-268.

Kahn, R. L., S. H. Zarit, N. M. Hilbert, and G. Niederehe. 1975. Memory complaint and impairment in the aged. The effect of depression and altered brain function. Archives of General Psychiatry 32(2):1569-1573.