3

Health Literacy and Medications

The workshop’s first panel session featured three presentations addressing progress in the field of health literacy and medications. Ruth Parker rofessor of medicine ediatrics and ublic health at the Emory University School of Medicine, provided an overview of the field’s progress. Gerald McEvoy, assistant vice president of drug information at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, discussed the progress that has been made creating a standard and best practices for medication prescription labels. Theresa Michele, director of the Division of Nonprescription Clinical Evaluations at FDA, then described the efforts that her agency has made in the health literacy area. An open discussion moderated by George Isham followed the presentations.

To begin her presentation, Parker recalled that when the committee that produced the 2004 report first met in 2002, approximately 10,000 prescription drugs and more than 300,000 over-the-counter (OTC) products were on the market. At the time, prescription drugs accounted for 10 percent of U.S. health care expenditures, which was double the level in 1980. The average American over age 65 was taking six or more medications prescribed by multiple doctors. “It was confusing, puzzling, and if you

_______________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Ruth Parker, professor of medicine, pediatrics, and public health at the Emory University School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

will, frustrating to patients,” said Parker. “A lot of folks knew that things could be better.”

Parker looked at this problem of health literacy as it applies to medications as a puzzle, with pieces of this puzzle represented by patients, prescribers, pharmacists and pharmacies, research, the timing of an increased focus on quality, the development of collaboratives, those who influence policy and public behavior, and the IOM. Starting with patients, she recounted collaborating with colleagues to listen to more than 35 hours of videotaped interviews of patients describing their struggles with understanding drug labels, and she remembered thinking at the time that “if we can get the word ‘twice’ [as in twice daily] off of every pill bottle, I am going to retire.” Ten years later, she’s still hoping for that to happen.

The variability in the way medication directions were given on drug labels was overwhelming despite the work of FDA and a system it had put in place to standardize the contents on labels. “From a patient standpoint, it was a non-system. It was broken,” said Parker, and the result was that patients were getting different content from different sources, whether it was the drug label itself, the pharmacist, or the prescribing physician. Physicians, for example, used different terms, sometimes even on the same prescription sheet, for “take one tablet twice daily,” and even today they still use Latin terms when ordering medication for their patients. Ten years ago, those Latin orders would often end up on the label on the pill bottle, though there were pharmacies and health care systems even then that were starting to change that practice and trying to figure out how to provide more consistent and easy-to-understand information for patients.

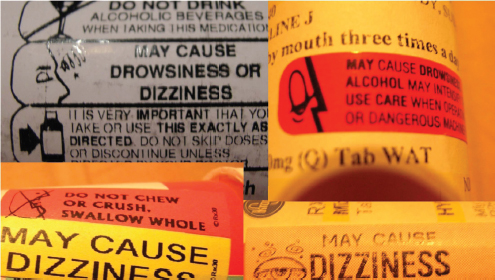

As far as what constitutes label information that patients might receive, there is the actual container label, the Consumer Medication Information (CMI) sheet that gets stapled to the bag, the package insert, and medication guide. Parker said that 10 years ago, it was not clear what kind of information was included in the CMI and whether it was even evidence based. There were also questions about the real purpose and clarity of the package inserts and the medication guides, which were and still are approved by FDA. “Are they really for the patient, or are they for the prescriber?” said Parker. She also noted that the pill bottles themselves are often cluttered with warning stickers (see Figure 3-1). “I remember Alistair Wood2 saying a pill bottle looked like a Christmas tree, with precious little real estate with all of those colorful little sticky things on it,” said Parker, “and when you really got down to it, there wasn’t a lot of evidence driving the content that was taking up this very precious real estate.”

Research became a piece of the puzzle when investigators started looking at the information consumers receive about medications and trying to

_______________________

2 Dr. Wood developed a uniform medication schedule that standardized dosing times.

FIGURE 3-1 Examples of the confusing array of warning labels on prescription pill bottles.

SOURCE: Parker, 2014.

figure out what patients get from this information and how it was presented to them. She recounted a study that she and her colleagues conducted that found that prescriptions written during one 8-hour period in one health system used 53 different phrases for “take one tablet a day” and that the translations of those phrases varied significantly (Bailey et al., 2009). One lesson from this study was that while drug container labels look simple, they are not clear. “The ability to read them doesn’t mean that you can actually interpret them or safely and effectively take the drug, which is what FDA wants to make sure you are able to do,” said Parker.

Mistakes were also common and increased with the number of drugs a patient took. They were also more frequent in individuals with low health literacy. Studies such as this one led to the conclusion that variability in dosing instructions is a root cause of some of the confusion patients experience with regard to their medications. Parker said one of the biggest lessons from the field of health literacy is that patients are actually experts on what they need in terms of drug information, and that partnering with them is important if the difficult challenge of making drug information understandable and actionable is going to be solved.

Over the past decade, a framework for health literacy has been developed that puts health literacy at the intersection of skills and abilities with demands and complexities, Parker explained, and it was the paradigm shift that Koh described of aligning demands and complexities with skills and

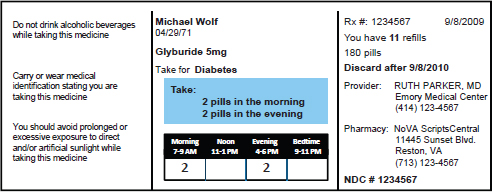

abilities that enabled the field to start making progress in creating health-literate drug information. One thing this paradigm shift led to was the development of consolidated medication regimens consisting of a small number of uniformly defined time intervals, rather than random intervals spread across the day (Wolf et al., 2011a). Parker and others have been developing reprogrammed medication labels (see Figure 3-2) that are more systematic and consistent in the way they present information to the patient, and as a result, are more likely to be correctly interpreted compared with standard instructions (Wolf et al., 2011b). In addition, they are developing instruction sheets that reduce the cognitive load on patients by using plain language, sequencing information in an order that makes sense to the patient, and only using visual aids that are meaningful (see Figure 3-3). Drop-down menus in electronic prescribing modules that use simplified and consistent pharmacy signature codes are also proving useful for creating labels and instruction sheets with standardizing language.

Instructions for pediatric liquid medications need improving, too. Dosing instruments, concentrations, and units of measures vary greatly, leading to confusion about how to give drugs to children. During the H1N1 influenza outbreak in 2009, for example, parents were instructed to give their children a dose of three quarters of a teaspoon of Tamiflu oral suspension, but the syringe included with the prescribed drug package was marked in a unit of milligrams, not fractions of a teaspoon (Parker et al., 2009). This confusing dosing information led FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to issue a warning (Budnitz et al., 2009).

Perhaps the most important shifts occurred when health literacy become framed as an issue of patient safety, and again when health literacy became linked with self-management as one of the priorities for

FIGURE 3-2 A reprogrammed prescription label.

SOURCE: Parker, 2014.

FIGURE 3-3 A simpler, more straightforward medication instruction sheet.

SOURCE: Parker, 2014.

transforming the quality of health care in the United States, said Parker. A 2007 Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations report (Joint Commission, 2007) was particularly important for raising awareness about the link between health literacy and patient safety and for prompting the formation of collaboratives to address the challenges of creating patient-friendly medication information. Parker noted the involvement of a wide range of organizations that have become involved in this effort since it was first raised at an AHRQ conference in 1999, including federal and state legislatures, the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP), numerous professional medical societies, the Latino Coalition for a Healthy California, the National Consumers League, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and even the mass media. Between 1999 and 2000, for example, the number of references to health literacy on television and radio increased from 7 to 128.

Parker noted the American Medical Association has been holding discussions about health literacy since the late 1990s, and Healthy People 2010 and 2020 have specifically highlighted the importance of health literacy to achieving national goals for improving the health of the nation. Surgeons Generals have been outspoken about health literacy. For example, Richard Carmona, who was Surgeon General from 2002 to 2006, mentioned health literacy in 200 of his last 260 speeches. She also applauded the work of the IOM, which has held 15 public workshops on health literacy, including workshops on how to align demands and complexities and on FDA’s Safe Use Initiative and building better patient-centered outcomes. The IOM’s publication of workshop proceedings over the years shows steady growth in efforts to continue to understand, build and support better patient-centered and health literate outcomes

She concluded her remarks by noting that the puzzle is not yet complete. “When the 2004 report came out I think we all felt good about the vision it laid out for a society in which people have the skills they need to obtain, interpret, and use health information effectively and within which a wide variety of systems and institutions do take responsibility for providing clear communication and the support to facilitate health-promoting actions,” said Parker. “I think that is still the vision that we share. Once we get that we will actually finish the pieces of the puzzle.” As a final note, she recounted a famous quote attributed to many sources: “It is amazing what you can do when you don’t care who takes credit.”

CREATING A STANDARD AND BEST PRACTICES FOR MEDICATION PRESCRIPTION LABELS3

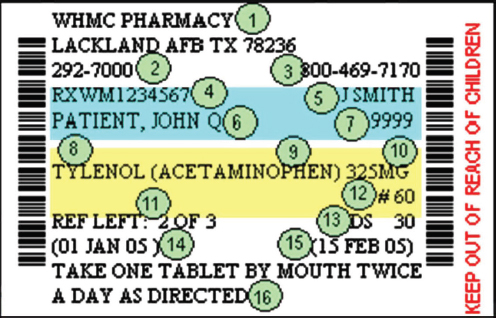

In his presentation, Gerald McEvoy focused on a USP initiative to develop standards for medication labels. He began his remarks by noting the confusing array of information that is included on the standard prescription label (see Figure 3-4), which historically features the name of the pharmacy as the most prominent piece of information. Over time, he noted, that information will become less prominent, and he acknowledged that progress toward creating more patient-friendly labels was being made before USP undertook its current effort and began issuing recommendations. Companies such as CVS and Target and health systems such as the Veterans Health Administration, for example, engaged experts such as Parker and others to assist them in designing labels even before standards became available.

The stimulus for much of this work, McEvoy said, was a white paper—Improving Prescription Drug Container Labeling in the United States: A Health Literacy and Medication Safety Initiative—that was commissioned by the American College of Physicians Foundation and presented at an October 2007 IOM Roundtable workshop. Two key findings noted in this white paper were that there was an inadequate understanding of the prescription container by patients that led to poor adherence, and that there were no universal standards for prescription labels. Other key findings in this white paper included

- Evidence-based practices should guide label content and format.

- Prescription instructions are important for patients and should be clear and concise.

- Patient medication information should be an integrated system that extends beyond the container.

- Health care providers are not communicating adequately to patients. • Research is needed to identify best practices.

McEvoy also listed the following major messages to come out of that IOM workshop:

- The container label is the patient’s most tangible source of information about prescribed drugs and how to take them.

- The container label is a crucial line of defense against medication errors and adverse drug effects.

_______________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Gerald McEvoy, assistant vice president of drug information at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

FIGURE 3-4 A standard prescription drug label presenting an array of information that is often confusing to patients.

SOURCE: McEvoy, 2014.

- Forty-six percent of patients across all levels of literacy misunderstood one or two dosing instructions.

- Fifty-four percent misunderstood one or more auxiliary warnings.

At that workshop, Alastair Wood presented his concept of the universal medication schedule and Roger Williams (then Chief Executive Officer of USP) offered to have USP convene a neutral, multidisciplinary group to develop prescription container labeling standards, an offer that many workshop participants endorsed. This offer was followed by the USP Safe Medication Use Expert Committee authorizing an advisory panel to determine an optimal prescription label content and format in order to promote safe medication use by critically reviewing factors that promote or distract from patient understanding of prescription instructions and to create universal standards for label format, appearance, content, and language. This advisory panel, which McEvoy and Joanne G. Schwartzberg co-chaired and that included Parker, Cindy Brach, and other health literacy experts, was formed in December 2008 and published the initial draft universal standards in January 2011. The standards became official in May 2013, with draft revisions focusing on visual impairment and patient-centered dosing expected to be posted for comment sometime

during 2015. The standards are available for downloading through the USP website.4

McEvoy noted that the decision was made to publish the initial set of standards based on top-level principles without waiting for additional evidence to more fully support detailed recommendations because enough things needed to be addressed and corrected in order to organize the information in a patient-centered manner. For example, the name of the pharmacy or its logo are not particularly important to patients, but how to contact the pharmacy with questions is important. In creating the standards, the advisory committee focused on issues such as improving readability, optimizing the label’s topography, and simplifying language. Discussions included topics such as whether to include the purpose of the drug—some patients do not want that information on the label for confidentiality reasons, but having that information is particularly important for the elderly, who often take multiple medications. Auxiliary information was a big focus of the advisory committee’s work and the ultimate recommendation was to minimize auxiliary information because there often is limited evidence to support that information and because it was distracting to patients.

Today, the standards are at what McEvoy characterized as at a high level, but he expects that over time they will become more specific in terms of how to standardize content and format as published evidence expands and strengthens. Currently, the standards stress that the prescription label be patient centered, that the information must be organized in a way that best reflects how most patients seek out and understand medication instructions, and that prescription container labeling should feature only the most important patient information needed for safe and effective understanding and use. The standards also state that the language on the label should be clear, simplified, concise, familiar, and free of jargon; that it is used in a standardized manner in sentence case; and that it should not use all capital letters. Instructions on the label should clearly separate the dose itself from the timing of each dose and should convey the number of dosage units to be taken, the timing of the doses using specific time periods—morning, noon, evening, and bedtime—and use numerals instead of letters for numbers. The standards note that dosing by precise hours of the day makes it harder for patients to follow.

The standards further state, McEvoy continued, that if the purpose of the medication is included on the prescription, it should be included on the prescription container label, though confidentiality and patient preference may limit inclusion of the purpose on labels. If the purpose is included, it should be in clear, simple terms and not use medical jargon—for example,

_______________________

4 See http://www.usp.org/usp-nf/key-issues/usp-nf-general-chapter-prescription-containerlabeling/download-usp-nf-general-chapter-prescription-container (accessed May 11, 2015).

high blood pressure should be used rather than hypertension. When in doubt, those writing the label should refer to the Plain Language Medical Dictionary available at the University of Michigan library website.5 Readability is important and the standards stress that labels should be designed and formatted with horizontal text so that the need to turn the container to read lines of text is minimized, that critical information is not truncated or abbreviated, and that the number of colors and their use should be minimized.

The important thing to remember about these standards, said McEvoy, is that USP is not a regulatory body and has no regulatory authority for this particular type of activity. Instead, states have to endorse the USP standards if they are to have the force of law because that is where the practice of both pharmacy and medicine are governed, he explained, though standards of practice can still apply when state regulations do not specifically endorse or preclude them. In 2011, California became the first state to require patient-centered labels, and the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy adopted the USP standard in a 2012 resolution that encourages individual states to adopt the standards. New York and Utah and perhaps others have since adopted some supportive language, and some national pharmacy chains have pre-empted state adoption to the extent permitted by state laws.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practice, the National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP), and other groups have also voiced support for the standards. NCPDP in particular, said McEvoy, can promote rapid adoption of the standard because it is the group responsible for electronic data standards that apply to medicines. He noted that NCPDP has published a white paper on acetaminophen label best practices (NCPDP, 2013), and these recommendations—including the one to replace APAP with acetaminophen and fully spell-out the ingredient for all combinations—were adopted quickly by the major pharmacy chains. Today, nearly 97 percent of U.S. pharmacies have adopted the recommended changes for acetaminophen-containing medications, including standardized warnings about liver toxicity and avoiding inadvertent concomitant use of multiple acetaminophen-containing products. In addition, the APAP abbreviation has been eliminated from the databases of every major medical publisher.

NCPDP has since released a second white paper containing recommendations and guidance for standardizing dosing designations on prescription container labels of oral liquid medications (NCPDP, 2014). The recommendations in the white paper include using milliliter as the standard unit of measurement and discontinuing the use of household units of measure

_______________________

5 See http://www.lib.umich.edu/taubman-health-sciences-library/plain-language-medical-dictionary (accessed May 11, 2015).

such as teaspoons, providing a dosing device with numeric graduations corresponding to the labeled dose, and always using leading zeros before a decimal point and never use trailing zeros. The white paper also recommends educating patients and caregivers about oral medications and educating pharmacy staff about the importance of using milliliters as the unit of measure for all oral liquids. CDC, FDA, USP, and professional practice groups have all voiced support for these recommendations, as have several large national pharmacy chains. Pharmacy database producers are facilitating easy adoption by converting household units to milliliters, and schools of pharmacy are now being asked to advocate the recommendations, which McEvoy said have received widespread national press coverage.

As far as the future goes, McEvoy reiterated that two proposed revisions will be available for comment. Revisions to address visual impairment incorporate the June 2014 U.S. Access Board Best Practices for the Visually Impaired (U.S. Access Board, 2013), which were authorized by the FDA Safety and Innovation Act signed into law on July 9, 2012. The revisions concerning more specific recommendations about using patient-centered instructions will refer to the Universal Medication Schedule (UMS), which schedules medication taking into four standardized time periods and which is particularly useful for simplifying daily medication regimens that include multiple oral therapies. McEvoy recalled visiting his parents and finding that they put out 10 to 15 cups of pills each day, each for a specific time of day ordered by their doctors. Randomized controlled trials have shown, however, that patient-centered labels using UMS improve understanding in a population that takes an average of five drugs: from 59 percent for standard labeling to 74 percent for UMS. Data also show improved adherence over 3 months from 30 percent for the standard label to 49 percent for UMS (Wolf et al., 2011b).

HEALTH LITERACY AT THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION6

In the final presentation of this panel session, Theresa Michele decided to eschew speaking about what has transpired over the past decade at FDA and instead talk about ongoing agency projects, both for prescription and OTC medications. She noted that none of this work would have been possible without the advances and paradigm shifts that the prior speakers discussed.

One of the things that concerns FDA about prescription drugs is that

_______________________

6 This section is based on the presentation by Theresa Michele, director of the Division of Nonprescription Clinical Evaluations at FDA, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

there are “too many cooks in the kitchen,” said Michele, meaning that patients are receiving prescription drug information from too many different sources that may be duplicative, incomplete, or difficult to understand. When patients pick up their drugs from the pharmacy, they receive medication guides and patient package inserts that are developed in collaboration with FDA, but they also receive consumer medication information that is not vetted by the agency. As a result, FDA is now considering a new regulation to require that all prescription drugs have a single, standardized Patient Medication Information (PMI) document. “They will get one piece of paper when they leave the pharmacy, and that would be for every prescription,” explained Michele. She stressed that this information will not replace patient counseling, which she said is absolutely crucial for reinforcing physician orders. Most importantly, the source of information in the PMI would be the FDA-approved professional labeling information.

Since it started this effort in September 2010, the agency has held a variety of expert meetings and public workshops to solicit input regarding the content and form of the PMI. For the most part, this idea has been well received, said Michele. The most recent of these workshops, held in July 2014, explored lessons learned from health literacy researchers engaged in the PMI projects and the role of stakeholders who regularly interface with the PMI in moving the initiative forward. FDA is now working on developing a framework for the PMI that is being informed by research and input from stakeholders. Some of the principles that the agency is considering in the development of the PMI framework include

- The agency will take a surveillance approach that includes reviewing and approving manufacturer-authored PMI;

- All information in the PMI will be based on FDA-approved professional labeling;

- The PMI will undergo consumer testing for comprehension, as is now done for OTC medications; and

- The PMI will be updated when certain changes are made to the professional labeling.

Another effort in the prescription drug area comes out of the FDA Safety and Innovation Act of 2012, and in particular Section 907, addressing issues related to demographic subgroups in clinical trials. The FDA Action Plan focuses on three key priorities, said Michele: quality in terms of improving the completeness and quality of demographic subgroup data collection, reporting, and analysis; participation with regard to identifying and breaking down barriers to subgroup enrollment in clinical trials; and

transparency as far as making demographic subgroup data more available and transparent to physicians and consumers who might benefit from those data. FDA is developing a website with a standardized consumer-friendly format that will be online soon, she said. These data are now available, but they are hard to find and are not useful to the general public.

Turning to the subject of OTC medications, Michele explained that the main focus of FDA’s activities is with the Nonprescription Safe Use Regulatory Expansion (NSURE), which would allow the use of innovative technologies or other conditions of safe use to expand which drug products can be considered nonprescription. To better explain what is involved in this effort, she first discussed some of the issues with the current system of regulating OTC drug products. In general, she said, OTC products have a few defining characteristics. They can be adequately labeled so that the consumer can self-diagnose, self-treat, and self-manage the condition being treated, and they can be used safely and effectively without input from a health practitioner. In addition, OTC products have low potential for misuse and abuse and they have a safety margin such that the benefits of OTC availability outweigh any risks associated with the product.

OTC drug candidates are tested to make sure they have these characteristics, typically using consumer studies. Michele explained that FDA requires a variety of consumer studies that look at label comprehension, self-selection, and actual use by patients. “These studies have evolved significantly over time to become much more sophisticated and much more in line with what we would expect for Phase III trials in prescription drugs,” said Michele. Currently, though, information to the consumer is limited to the small space on the drug facts portion of the product label, and FDA wants to ensure that OTC drugs gain wider use because of the difficulty that some patients have gaining access to the health care system. “We want to help patients take charge of their own health,” she explained.

Michele acknowledged that there were many misconceptions about what NSURE was trying to accomplish. Some stakeholders, for example, thought NSURE was trying to eliminate doctor visits, which is not the intention. Rather, NSURE aims to help people who are sitting in the pharmacy without seeing a doctor, not to stop those who want to see a doctor from doing so. Another concern FDA heard from stakeholders was that FDA was going to create a third class of drugs, but the agency has no intention of doing that, and NSURE is not designed to give prescribing powers to pharmacists. The latter, in fact, is regulated by the states. “What we are trying to do is expand the pie a little bit for those products that could be non-prescription if people had the health literacy abilities to understand how to use them,” said Michele in closing.

Betsy Humphreys, deputy director of the National Library of Medicine (NLM), started the discussion by noting that NLM appreciates the collaboration it has with FDA in terms of making approved drug labels available through the DailyMed website and for helping keep prescription standard terminology up to date. She then asked about the use of the PMI in cases where a patient has other comorbidities that would alter how they use a particular drug or where there are other factors that conflict with the standard information in the PMI. Michele replied that every great idea comes with stumbling blocks, and it is important to address as many as possible ahead of time, which is what FDA is doing with the PMI. She reminded the workshop that the PMI is not meant to replace individualized counseling or the special instructions that come with certain medications, such as those that use metered-dose inhalers or an auto-injector.

McEvoy continued on this theme by asking about off-label use, which is more common and more important for many drugs. As an example, he noted that methotrexate was used off-label to treat arthritis long before it was approved for that specific use. “Imagine the patient who got a PMI that only talked about cancer as the use for that particular drug. That is an important issue,” said McEvoy. Parker added that part of the vision for the future of the medication label is to develop a more standard approach to the instructions on the label, which, as she put it, is where the rubber meets the road for the actual patient. “We want to see that become a piece of the clinical trial that brings a medication to the market, where the data from the trial actually reflect the reality of what it is that ends up on the label and what ends up happening with the actual person consuming the products,” said Parker.

Humphreys then asked about the challenges of providing demographic breakdown data given that some of these data are not too accurate and wondered about the level of expertise that would be needed to assess the data. Michele said she could not agree more that it would not be useful to report on a tiny subgroup, and that additional feedback from the field will help FDA determine what kinds of data are useful and how they can best be presented.

Laurie Myers, lead of the Healthcare Disparities and Health Literacy Strategy group at Merck & Co., Inc., then asked Michele if she had any idea about the timing of the PMI framework and its implementation given that it has been in the works for a number of years. Michele responded that she could not say that anyone other than FDA is working on it, particularly with regard to meeting the needs of patients with low health literacy. Isham commented that the widespread availability of cell phones and other technologies may provide some opportunities for addressing some challenges

that come with low health literacy. Michele noted that FDA is considering all options as part of the NSURE Initiative, and has asked the pharmaceutical industry for any creative ideas it may have.

Parker noted that a recent meeting of the IOM Roundtable on Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities was well attended by technologists; there are now nearly 700 apps available to help with medications. She also remarked that cell phones are particularly popular with some of the underserved populations that might have issues with low health literacy. On the other hand, cell phones are becoming an increasing cause of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) violations when used to communicate with patients. This is particularly true when patients text pictures of their medications when asking for advice. McEvoy added that the Office of the National Coordinator Meaningful Use Stage II Requirements for Electronic Health Records requires that there be patient access to information in context. What that means, he explained, is that if a patient accesses his/her electronic health record (EHR) portal using his/ her cell phone to get information about his/her medications, that EHR must provide the in-context access to information about those drugs. “That is already being adopted and the government is stimulating it,” said McEvoy.

Thinking about how hard it is sometimes to decide which OTC product to take for a particular self-diagnosed illness, Isham asked the panelists if they had any thoughts about how drug labeling for OTC medications might integrate with a larger system for helping the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions. Michele replied that that would be a tall order. “I think OTC consumers get their information in a variety of different ways, and we need to reach out to them beyond just what is on the pharmacy shelf,” she said. One FDA program, called Medications in Your House, not only reaches out to the adult consumer, but is meant to be used as a middle school curriculum to educate budding adults who will soon need to understand what is on the pharmacy shelf and what is in their medicine cabinet.

“We need to be creative in this space because it’s not just about what is on that drug facts label,” said Michele. In the prescription drug space, all information should flow from the package insert, which FDA controls tightly even with regard to advertising. “In the OTC space, the drug facts label is just a small part of what the consumer sees,” she added, noting that the first thing the consumer sees is what is on the front of the box, which may not even say what the names of the drugs are in the product.

Parker noted that as a health care practitioner, her health literacy has been advanced by being part of FDA Advisory Committees. “I think FDA’s willingness to have those of us who are engaged in this field be a part of the conversation to become educated and health literate ourselves about

the nuances of a regulatory agency and what it takes to make progress and what to change has really contributed to my lens of what it is about. I am very appreciative of their allowing us to be a part of the table,” said Parker. She added that she has come to appreciate the fact that a regulatory agency such as FDA should not move too quickly with regard to issues such as these that are highly nuanced. As an example, McEvoy cited issues having to do with product branding, such as the decision of the maker of the cold product Sudafed to develop a formulation that did not include pseudo-ephedrine, which had been relegated to behind-the-counter status because of its potential use in making illicit drugs, and call it Sudafed PE. “This may not seem important but it really is,” said McEvoy. “Patients will draw their conclusions about what that product is intended for because of the history they have with that brand, so how do we balance the importance to the manufacturer of the brand versus solving that particular issue?” He also cited acetaminophen as another example because the United States is the only country where the generic name for that drug is not paracetamol. With the large number of immigrants in this country, it is important that acetaminophen also be identified as paracetamol to prevent accidental overdosing by someone who is not familiar with the U.S. name for this drug.

Isham concluded the discussion, noting that it illustrated a few important points, including the facts that (1) very capable individuals are addressing these issues, and (2) the need of consumers to treat themselves and the need to do it safely is a complex interface. Finally, he said the discussion has demonstrated the progress the field has made and drawn a clear line to some of the activities of the Roundtable, yet at the same time it points out that much more progress needs to be made to solve the issues of health literacy and medication safety.