The workshop’s third panel session included presentations by three speakers. Rima Rudd, senior lecturer on health literacy, education, and policy at the Harvard School of Public Health, provided an overview of where the field started and where it has progressed to in terms of education and health literacy. Barbara Schuster, Campus Dean, Georgia Regents University/University of Georgia Medical Partnership, addressed professional education, and Lindsey Robinson, a practicing dentist and trustee of the American Dental Association, discussed the role of education in oral health literacy. An open discussion moderated by Roundtable Chair George Isham followed.

Rudd began her review by reminding the workshop about the clearly articulated recommendations that the IOM offered in the 2004 report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. These included

- Recommendation 5-1: Accreditation requirements for all public and private educational institutions should require the implementation of the National Health Education Standards (NHES).

____________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Rima Rudd, senior lecturer on health literacy, education, and policy at the Harvard School of Public Health, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

- Recommendation 5-2: Educators should take advantage of the opportunity provided by existing reading, writing, oral language skills, and mathematics curriculum to incorporate health-related tasks, materials, and examples into existing lesson plans.

- Recommendation 5-3: HRSA and CDC, in collaboration with the Department of Education (DOE), should fund demonstration projects in each state to attain the NHES and to meet basic literacy requirements as they apply to health literacy.

- Recommendation 5-4: DOE in association with HHS should convene task forces comprised of appropriate education, health, and public policy experts to delineate specific, feasible, and effective actions relevant agencies could take to improve health literacy through the nation’s K-12 schools, 2- and 4-year colleges, and universities, and adult and vocational education.

- Recommendation 5-5: The National Science Foundation (NSF), DOE, and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) should fund research designed to assess the effectiveness of different models of combining health literacy with basic literacy and instruction. The interagency Education Research Initiative, should lead this effort.

- Recommendation 5-6: Professional schools and professional continuing education programs in health and related fields, including medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, social work, anthropology, nursing, public health, and journalism, should incorporate health literacy into their curricula and areas of competence.

Of these, only the second and sixth recommendations, to integrate health literacy with literacy skills and that professional schools incorporate health literacy into their curricula, have strong illustrative examples. One example of follow through on the second recommendation was then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s Health Literacy initiative in New York City. The initiative started with a partnership between Harvard School of Public Health and the Literacy Assistance Center of New York City. Adult education teachers in each of the five boroughs were engaged in a series of half day meetings that enabled them to integrate health literacy skills into their adult education ABE (adult basic education), GED (general education development), and ESOL (English for speakers of other languages) classes. Rudd noted that the tools and materials her team developed were tested in New York and then widely disseminated throughout the United States. Examples of follow-through on the sixth recommendation include health literacy courses that were first developed at the Harvard School of Public Health, the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, the University of Chicago Medical School, and the University of West Virginia Medical

School. Health Literacy classes and modules and are now increasingly being included in medical schools, dental schools, and pharmacy programs. Sadly, said Rudd, there are still a number of barriers to wider adoption of health literacy coursework, with the main one being the perception that there is no room in the curriculum to add another requirement. One comment she has heard has been that until competency in health literacy becomes a requirement for licensing, nothing much will get done.

In contrast, the non-formal health literacy education has flourished over the past decade, something that Rudd said was not in the IOM’s thinking when it developed this recommendation. Nonetheless, health literacy courses are also being included in professional continuing education offerings and are being made available as part of online courses, toolkits, training programs, workshops, and conferences. There has been what she characterized as a wonderful diversity of examples in the non-formal sector, where community education projects were developed. Many of these projects have only appeared in the gray literature given the difficulties in publishing studies that do not have overt links to health outcomes.

Regarding the third recommendation about demonstration projects, she said that the vision turned out be much more expansive than what actually happened, for there was not a regular effort in every state. Neither was much done as far as the development of partnerships between funding agencies. “That is not to say that there have not been incredibly interesting and exploratory work and really wonderful demonstration projects, but they didn’t have the impact on the national level that I think the recommendation was really trying to speak to, nor did the partnership work with the National Science Foundation,” said Rudd, who added that this is still a worthwhile goal. Much remains to be done in integrating health literacy insights and findings into broad public health efforts. In some ways, she added, global climate change debates and the panic over Ebola represent failures in health literacy.

Rudd said that some may ask why progress has been so slow given that the argument supporting health literacy insights is sound. After all, she said, the links between literacy skills and health outcomes has been well-documented, as have the poor findings of U.S. adult literacy skills, the mismatch between the skills of individuals and the demands of health systems, and the implications of poor health literacy with regard to disparities in health and in care services. Some difficulty can be attributed, Rudd noted, to the evolving concept of health literacy (Chinn, 2011). While Howard Koh spoke about paradigm shifts, there is also a shift under way in our understanding of what constitutes health literacy, what it means, where the locus of responsibility lies, and how contextual issues will be brought into the equation, explained Rudd. It is only recently, she added, that the field broadened its vision of health literacy from its initial focus on the skills

and deficits of patients to one that now includes attention to the skills of health professionals and the contextual factors of institutions in health care, public health, and social services. As many speakers at the workshop noted already, there is a new focus on institutions that includes not only their behaviors, but also the culture and norms that shape practice and policies. “It is only when we pay attention to all of these areas that we benefit the patient, the individual, and the community,” said Rudd.

She then offered some theory-based analysis to explain why progress has been slow, turning first to Kurt Lewis’s work on force field analysis. Force field analysis requires first analyzing the current situation before articulating a vision for change. The current situation in this case refers to the state of the field in 2002 to 2004 when the report was being assembled, and the articulation of change contained in the recommendations in that report. Force field analysis also requires carefully identifying the facilitating forces and the barriers to be removed before change is possible.

The context at the turn of the 21st century was one of excitement given the multiple DOE reports earmarking adult literacy starting in 1992; the Healthy People 2010 health literacy objective that came out in 2000; the HHS health literacy action plan released in 2003; the 2002 NIH Conference on Education, Literacy, and Cognition; the NLM’s preparation of annotated bibliographies on health literacy; The Education Testing Service’s population-based Health Literacy Analysis published in 2004; the 2004 American Medical Association report Understanding Health Literacy; AHRQ’s systematic review of the field in 2004; and the 2004 IOM report, among others. Rudd remarked that her European colleagues are amazed key players pushing the health literacy agenda were from government.

An important facilitating force for individual researchers at the time, Rudd said, was that it was a new field in which young researchers could make their mark. White papers, editorials, dedicated conferences, and workshops provided further incentives for researchers to join this nascent field. In addition, health literacy represented a malleable variable to address disparities and it held the promise for potential cost savings as well. There were also restraining forces, including the fact that health literacy challenged existing norms and common practices of already overburdened health care systems and was an implicit critique of the job that the health care community was doing. There was also little focus on efficacious action, that is, on understanding what to do differently or how to do it differently.

There were also constraining as well as restraining forces. There was a budget crisis then involving cuts and sequestration that included severe cuts to funding for adult education. Even well-designed and -tested health literacy educational programs for staff developed by CDC and the Veterans Health Administration, for example, were never fully deployed because of

budget cuts. Social and political distractions were also operating over the past decade, including the passage and subsequent challenges to the ACA.

The strategic action that force field analysis calls for is not only to understand the current state in order to identify a strategy, but action to remove barriers. Rudd wondered if the field might have done better work if everyone had not been so focused on the facilitating factors and had paid more attention to the strategic action of identifying restraining forces.

Another theory that provides insight is Everett Rogers’s articulation of Diffusion of Innovation. Diffusion, according to this theory, is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among members of a social system. Each of these key components (the processes, the innovation, the types of communication, the channels of communication, time, the various players, and the social system) has characteristics that can support or impede diffusion. A strategic action plan can focus on re-shaping some of the components to help with the spread of ideas and with the adoption process. When health literacy is analyzed as an innovation it offers implications for practice, institutional change, and modification for the way health materials are developed. Analyzing an innovation entails paying attention to relative advantages, compatibility with existing systems and ideas, and its trialability, complexity, and observability. The relative advantages are mixed, she noted, particularly because health literacy can seem bothersome and costly in the short run. “Perhaps we could have paid more attention to some of those difficult elements and changed our approach a bit,” said Rudd.

Communication channels have been extraordinarily challenging, she continued. The myriad journals that speak to specific audiences require that the message about the value and importance of health literacy be repeated over and over again in multiple journals, at multiple conferences, and to multiple professional groups. Addressing the vast number of audiences in the health field has been exhausting, said Rudd. She also said that while everyone in the health literacy field feels the urgency of their mission, patience is important for the time it takes for knowledge to spread, for persuasion to take place, and for decision making and action to follow. In many instances, the field is still at the persuasion stage. Furthermore, the social systems involved are just now being addressed as researchers begin looking at the characteristics of institutions in both healthcare and public health.

Rudd said one challenge was that the field in the early days was populated largely by young researchers who did not yet have the gravitas that would get others to listen to them. “Things have changed over time and we have more gravitas to us,” said Rudd. The social systems involved are just now being addressed as researchers begin looking at the characteristics of institutions in both health care and public health.

The lessons from diffusion of innovation theory come from analyzing the decision process and the consequences of those decisions. This analysis requires examining carefully the key elements of the innovation and perhaps considering the reinvention and malleability of health literacy to adapt approaches that best fit the core needs of the members of health care and public health systems. “That may be why we didn’t resonate with education—a field overburdened by its own set of changes and challenges,” said Rudd. For future planning and strategic action, Rudd contended that conducting a diffusion analysis and force field analysis will help the field move ahead with greater precision. “That’s not to say that we should not celebrate today for indeed we should celebrate the accomplishments in health literacy education,” said Rudd, and the field should certainly celebrate the fact that government agencies and institutions have been incredibly supportive of these efforts. In closing, she noted that the rich array of educational resources and programs that have long been available and are still available for free online, both for health professionals and for institutions to adapt and adopt, thanks to the hardworking people in our government institutions.

HEALTH LITERACY IN PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION2

Barbara Schuster began her presentation by reviewing the educational requirements for various health care fields. For medical education, two bodies are involved. The Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME) is the accrediting body for allopathic medical schools, which have increased in number over the past decade to 140 schools. LCME’s Standard 7.8, Communication Skills, calls for the faculty of a medical school to ensure that the medical curriculum includes specific instruction in communication skills as they relate to communication with patients and their families, colleagues, and other health professionals. She also noted the role of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which oversees the allopathic residencies, postgraduate medical education that is required for licensure and specialty certification in the United States. Schuster noted as an aside that by 2020, all osteopathic residencies will also fall under the same jurisdiction. ACGME has six core competencies it requires in graduate medical education and one of them calls for competency in interpersonal and communication skills “that result in effective information exchange and teaming with patients, their families, and other health professionals.” ACGME core program requirements also state that “the

_______________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Barbara Schuster, Campus Dean, Georgia Regents University/University of Georgia Medical Partnership, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

residents are expected to communicate effectively with patients, families, and the public, as appropriate, across a broad range of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, and to communicate with physicians, other health professionals, and health-related agencies.”

There are also communication requirements in pharmacy education. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Standard 3, Approach to Practice and Care, states that pharmacy programs “must impart to the graduate the knowledge, skills, abilities, behaviors, and attitudes necessary to solve problems; educate, advocate, and collaborate, working with a broad range of people; recognize social determinants of health; and effectively communicate verbally and non-verbally.” Looking at the standards, there is good overlap between what is required in the education of physicians and pharmacists, said Schuster.

The American Association of Colleges of Nursing’s Essential Number 7, Clinical Prevention and Population Health, states that “health promotion and disease prevention at the individual and population level are necessary to improve population health and are important components of baccalaureate generalist nursing practice.” Sample content could include health literacy. It is not a required component, but nonetheless at least health literacy is mentioned specifically, said Schuster.

Examining these accreditation standards offers several take-away lessons, she said. Each of the accreditation systems lays out the competencies and requirements for educating professionals in their respective fields, but each individual school writes its own competencies and curriculum. The schools then have to demonstrate to the accrediting bodies that their curriculum meets the standards and their stated competencies. “That means that if I want to make health literacy a requirement, I need to write a learning objective in my curriculum, which is going to answer a competency for the school that then answers a standard for the accrediting body,” explained Schuster. “You can see how in the national standards, health literacy is almost never actually specifically stated as a requirement or standard.”

Nonetheless, the general expectation is that students are taught about health literacy in some form, and most schools would say that they do teach health literacy. Schuster said that she was fortunate when she came to Georgia to start the Athens medical campus, a partnership between the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University and the University of Georgia (GRU/UGA) because one of the young faculty members was one of Ruth Parker’s disciples and had learned the skills needed to conduct health literacy training while an internal medicine resident at Emory. This faculty member does not teach a formal course because Schuster’s campus does not offer courses in any subject, but rather has an integrated, facilitated case-based and skills-building curriculum that also includes community outreach and working with community agencies. Core skills building

in communication and physical examination is a critical component in this curriculum, and health literacy is an explicit part of this curriculum, which Schuster illustrated by listing the following learning objectives for first year medical students:

- Describe the extent of low health literacy and numeracy in the United States.

- Identify possible outcomes when patients misunderstand issues in clinical care settings.

- Describe ways to present health information to patients to help overcome misunderstandings due to low health literacy and numeracy skills without appearing condescending.

- Practice plain language and the “teach-back” method.

- Evaluate patient handout materials and make suggestions on how to improve them for low health literacy patients.

- Given a case scenario, recognize clues that might suggest a patient has low health literacy and/or numeracy skills.

- Given a case scenario, identify possible misunderstandings that may arise due to low health literacy and numeracy skills.

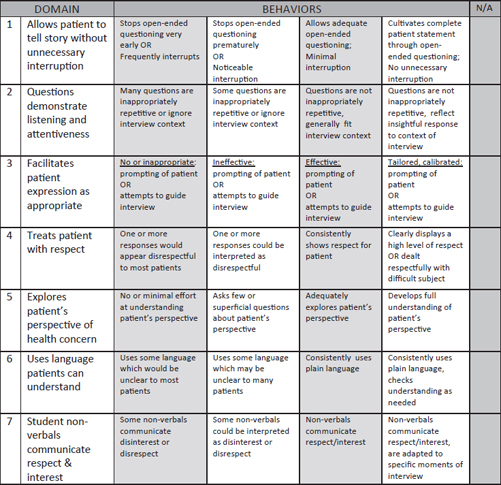

Not only do the students have to describe what health literacy and numeracy are, but they have to practice how to deliver concepts such as percentages and percentiles and to use teach-back methods that stress plain language. Everything the students write for patients, particularly during their projects in community health, is judged in part on their health literacy. All of their communications with volunteers who serve as “patients” are also judged on clarity and health literacy using a communication assessment tool (see Figure 5-1). For example, assessment item number six asks if the student uses language that patients can understand, and asks what behaviors the student exhibited, such as “uses some language that would be unclear to most patients,” “uses some language that may be unclear to many patients,” “consistently uses plain language,” and “consistently uses plain language and checks understanding as needed.” This assessment tool, she noted, continues to emphasizes good communication skills throughout the examination process.

Schuster said that once students leave their educational programs, it is important to continue stressing health literacy, and to illustrate her concerns she spoke about how the American College of Physicians (ACP) Foundation has changed. The ACP Foundation chose health communication as a major program area thanks to the role that Parker played in the formation of the Foundation, and as a result, health literacy was at the core of the Foundation’s mission. The ACP Foundation, in fact, helped facilitate some of the IOM’s early workshops on health literacy and supported the development

FIGURE 5-1 The Communications Assessment Tool used by the GRU/UGA Medical Partnership.

SOURCE: Schuster, 2014.

of some of the research papers that have helped move the field forward. In 2012, the ACP decided the Foundation would no longer be involved in health literacy, raising the question of who would champion health literacy going forward.

Schuster recounted how in 1975, when she was a third year medical student at the University of Rochester, Dr. John Romano, the chair of the psychiatry department would take every student to the state psychiatric hospital, where he interviewed patients in a very traditional manner. She remembered Romano saying to her and the rest of the students that the reason he took them to the state hospital was that they needed to learn as

physicians how to communicate with everyone, from the farmer that grows corn to the engineer who thinks in a black box. “That was very powerful as I sat there and watched this incredible person,” said Schuster.

She concluded her comments by noting that one of the big challenges that professional schools face is that they do not have faculty who have the background and skills to teach students about health literacy and to continually stress the need to communicate effectively and clearly to patients and their families. She told the story of a resident she once supervised who complained about a mother who repeatedly brought her child for care to the resident practice with an unresolved chief complaint. Schuster asked the resident to explain why. The resident responded said that he was writing out the instructions for the mother and that the instructions should have been clear. However, the resident had neglected to find out if the mother could read, which turned out to be the reason for the lack of communication and repeated clinic visits. “We need more faculty in nursing, pharmacy, and medicine who can teach these skills,” said Schuster. She also commented on the confusion that exists given that the regulations now talk about cultural competency, the use of translators, and communications as a whole, but not about the fine skills that the Roundtable has identified that are specific to health literacy.

There are opportunities. State organizations are now focusing on health literacy, as are interdisciplinary groups, which is important given that professional education is becoming increasingly interdisciplinary. As a last point, she returned to the question of who will champion health literacy. She asked in closing, “Will health literacy go the way of the bio-psychosocial model or evidence-based medicine, or will it become so enmeshed in professional education that there will be no further need for champions?”

EDUCATION IN ORAL HEALTH LITERACY3

It is the responsibility of the dental profession and its professional organizations to play a leading role in educating dentists and dental team members—hygienists and dental assistants—on the importance of oral health literacy, said Lindsey Robinson. The vision of the American Dental Association (ADA), she explained, is to be the recognized leader on oral health, and the mission of the California Dental Association (CDA) is a commitment to the success of its members in service to their patients and the public and to improve the health of all Californians by supporting the dental profession in its efforts to meet community needs, she explained.

_______________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Lindsey Robinson, a practicing dentist and Trustee of the American Dental Association, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

In 2000, the Surgeon General issued a report that put oral health on the map in terms of its importance to overall health and well-being (HHS, 2000). This report highlighted research findings that pointed to the possible associations between periodontal or gum disease, and diabetes, heart and lung diseases, stroke, low birth weight babies, and premature births, and it pointed out that dental caries is the single most common chronic disease of childhood, five times more common than asthma. This report was followed by the 2003 National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health, also from the Surgeon General’s Office (HHS, 2003), that stressed the importance of public–private collaboration, and a National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research report on oral health literacy released in 2004 (HHS, 2005). Research on oral health literacy also began appearing in the literature, particularly from groups headed by Jessica Lee and Gary Rozier at the University of North Carolina (Lee et al., 2013) and Alice Horowitz at the University of Maryland (Horowitz and Kleinman, 2008; Rozier et al., 2011). Since 2001, health literacy has been included in the annual sessions of most major dental organizations and government-sponsored meetings, Robinson added.

Other important developments raising the profile of oral health literacy included the adoption of a definition for health literacy in dentistry and a policy statement affirming its importance by the ADA House of Delegates in 2006, ADA’s establishment of a National Oral Health Advisory Committee in 2007, and the release of a Health Literacy in Dentistry Action Plan for 2010-2015. In 2009, ADA conducted the first surveys among U.S. dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants to assess the state of oral health literacy among dental professionals. That survey concluded that

- The number of communication techniques used routinely varies greatly among dentists;

- There was low use of techniques most commonly recommended by health literacy experts—only 20 percent of dentists used teach-back, for example;

- Routine use of health literacy techniques was similar to that of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists; and

- Of those who responded to the survey, 73.3 percent had never had a course in health communication, and 68.5 percent indicated interest in taking such a course.

CDA was also an important leader in the effort to raise awareness about oral health literacy, particularly through the April 2012 issue of the Journal of the California Dental Association that featured oral health literacy. Going through the table of contents of the April 2012 issue of the Journal of the California Dental Association, Robinson noted that the

issue included the ADA National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy in Dentistry (Podschun, 2012), three papers from the Horowitz group at the University of Maryland (Braun et al., 2012; Horowitz and Kleinman, 2012; Maybury et al., 2012), a paper calling for a multicultural paradigm shift in oral health care focusing on oral health literacy to address the demographic changes occurring in California (Centore, 2012), and a practical example of incorporating oral health literacy messages in community health efforts among a migrant farm community in Illinois (Bauer, 2012). One of the articles from the Maryland group showed that if dentists and hygienists do not understand the importance of early cancer prevention and do not know how to conduct an appropriate oral cancer exam, “the public is going to be in really bad shape,” said Robinson.

Another CDA initiative was the First Smiles program, which she explained was a $7 million program funded by the Tobacco Tax that was designed as an education and training program for dental and medical professionals on early detection and prevention of childhood caries. The materials developed for this program were translated into 10 languages for professionals to help them understand how to use preventive strategies, such as floride varnish, in a clinical setting.

Robinson noted that in 2007, CDA had released a consensus statement, Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA), which explicitly included oral health literacy and tools for improving oral health (Young et al., 2007). The CAMBRA movement, in which CDA has been heavily involved Robinson said, is a paradigm shift in dentistry with the goal of moving the treatment of dental caries from a surgical, restorative model to a chronic disease management model. To further this paradigm shift, CDA has developed health-literate tools and resources that are available on its website.

In 2010, the CDA Foundation collaborated with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, District IX, to issue the report Oral Health During Pregnancy and Early Childhood: Evidence-based Guidelines for Health Professionals. The report was the product of an expert panel that concluded that prevention, diagnosis and treatment of oral diseases is beneficial and safe during pregnancy. It established clinical guidelines for dental health professionals on treating pregnant women. “The goal was to make dental professionals understand that it was safe and it was their responsibility to treat pregnant women,” said Robinson. “It is amazing how many dentists still are very uncomfortable treating pregnant women.” A further goal was to encourage prenatal care providers to integrate oral health into the care of pregnant patients to optimize the oral health of both mother and baby.

CDA’s efforts now include funding a seat on the IOM’s Roundtable on Health Literacy. Robinson was also a co-author of a Roundtable discussion paper on the use of the after visit summary in dentistry (Horowitz et al.,

2014b). This paper makes the argument that the after visit summary is a powerful tool to assist in a patient’s self-management that could be used in dentistry and especially in an integrated health care environment where dentistry and medicine are practiced under one roof or closely associated with each other. Federally qualified health centers would be a good environment in which to promote health literacy and oral health literacy using the after visit summary as a resource in primary care, she said.

Robinson noted the importance of the Maryland Health Literacy Model that is centered on the prevention and early detection of dental caries. This model is meant to address the challenge of the mismatch between the demands of the health care system and the skills of those using the system and working within the health care system with the specific focus on the prevention of cavities in children, she explained. The goals of this effort include

- Establish local or state needs;

- Determine what the public knows and does regarding caries prevention and early detection;

- Determine public’s perceptions of provider communication skills;

- Determine what public agencies such as Head Start and Women, Infants, and Children know and do regarding caries prevention and early detection;

- Determine what health providers know and practice regarding caries prevention/early detection;

- Determine communication techniques of health care providers; and • Conduct environmental scans of dental facilities.

Research shows that the general public, at least in Maryland, does not understand how to prevent tooth decay, does not know what fluoride is and what it does with regard to prevention, or what sealants are and their uses. Often, members of the public do not drink tap water, which Robinson said was unfortunate because it is an inexpensive and cost-effective method proven to reduce or even eliminate tooth decay (Horowitz et al., 2013b). Surveys of health providers were concerning given that many health providers, including dentists and dental hygienists, do not have a good understanding of decay prevention. Many do not provide dental sealants in their practice, and most did not use recommended communication techniques (Horowitz et al., 2013a; Maybury et al., 2013). Based on these findings, the Maryland group has published recommendations for steps that dental professionals can use to improve communication with patients (Horowitz et al., 2014a).

Robinson then turned to ADA’s current efforts to improve oral health literacy. In 2014 the organization sent two staff members to the Institute for Healthcare Advancement (IHA) Annual Meeting to learn the basic

principles of oral health literacy. As a result of this experience, ADA is in the process of revising all of its patient education materials to conform to health literacy principles, and ADA’s Council on Access Prevention and Interprofessional Relations is providing content expertise for all IHA publications. In the week prior to this workshop, ADA convened a continuing education course called Health Literacy: Foundation of Patient Understanding and the organization has also reconvened the National Advisory Committee on Health Literacy and Dentistry. ADA will also take over funding of the Oral Health seat on the IOM Roundtable on Health Literacy and the organization is reviewing all of its policies to see if they can be updated to promote the use of health literacy principles.

Going forward, ADA is positioned to be the leader on health literacy in dentistry and is committed to continuing its support for the National Advisory Committee. The ADA Executive Director has also announced that the organization will work to adopt the 10 Attributes of a Health Literate Organization. In keeping with that announcement, ADA is implementing programs to educate its members about health literacy principles and is exploring opportunities to collaborate and support other organizations with the same goals of furthering health literacy in dentistry. As an example of how ADA is working to adopt the 10 Attributes, Robinson mentioned its effort with regard to Attribute Three: Prepares the workforce to be health literate and monitors progress. ADA is asking the Committee on Dental Accreditation to consider having health literacy included within the sections of the relevant standards for accrediting predoctoral dental education programs as a first step and will also explore including health literacy in actual standards.

CDA, meanwhile, will be working with the new California state dental director to incorporate health literacy principles within the work of state government and its programs aimed at improving the public’s oral health. Robinson noted, too, that the Maryland and North Carolina research groups are still actively researching issues related to health literacy in dentistry. The bottom line, said Robinson in closing, is that health literacy is inextricably linked to improving oral health, especially among low-income groups. “Each of us has a role, opportunity and responsibility to improve oral health literacy of patients, providers, and the public,” she said.

Cindy Brach, senior health policy researcher for AHRQ, began the discussion by asking Schuster if there was some role for continuing education programs to help professional school faculty become aware and supportive of the need for health literacy in medical professional education. She also asked if the development of curricula modules that schools could adopt

would be helpful given the findings that health professional school deans strongly support the health literacy movement and are trying to incorporate the subject in their curricula. Schuster responded that one challenge is to first determine what the competencies are that health professionals need to develop, and then modules might help. However, she noted that asking a student to complete a module, particularly online, does not lead to long-term retention and behavior change. What is needed is for instructors who are watching students as they interact with patients to actively review the students’ interactions and continually remind them about the importance of clear and effective communication. Brach agreed with Schuster’s critique of modules and explained that she was thinking more about exercises or assessments that faculty could use with students. Schuster replied that it is always good to have tools that faculty can use to assess their students’ actions. The most important step, though, is to include health literacy as a required competency. “If it doesn’t become a competency for their program then it doesn’t get counted and it doesn’t get done,” she said, noting that it is the responsibility of the faculty to write those competencies. She also added that her approach of integrating health literacy into other activities is to make them seem like they are not an add-on, but a natural part of what a student has to learn to be a competent health professional.

Following up on this idea, George Isham asked about the difficulty of including a health literacy standard into health professional education and if there might be some way for all health professions to work together to present a common front. Schuster replied that one approach might be for medical schools, pharmacy schools, nursing schools, dental schools, and others to work together as part of the intraprofessional education mandates that are common today.

Lori Hall, consultant on health education at the Lilly Corporate Center, asked Robinson if ADA had considered changing the term “oral health literacy” to “dental health literacy” to eliminate the confusion as to whether the reference is to health literacy as it applies to the mouth or to spoken communication. In fact, said Robinson, the ADA advisory committee just changed its name to the National Advisory Committee on Health Literacy in Dentistry, and she agreed that a change in terms might resonate better and make it more encompassing. “Dentists want to be thought of within the spectrum of health literacy and not standing by ourselves siloed as oral health literacy,” said Robinson. Steven Rush, director of the Health Literacy Innovations Program at UnitedHealth Group, agreed with Hall’s suggestion concerning renaming oral health literacy. He also expressed his thanks to Rudd for providing several frameworks for creating a business case that he could take to his organization.

Wilma Alvarado-Little, director of the Community Engagement/ Outreach Center for the Elimination of Minority Health Disparities at the

University of Albany, asked how a patient would know if a resident had completed the ACGME Core Program requirements for health literacy. Schuster said that the patient’s point of view is that the patient goes home knowing and having communicated with that care provider or that physician or resident in the room. “They feel good in that they have had their opportunity to ask the questions that they needed to ask,” Schuster said, adding that the unfortunate part is that the patient often does not know or say what they did not understand. “They are confused and go home not knowing it.” The challenge, she said, is to get health care professionals to a place where they not only communicate clearly, but can also pick up on the non-verbal cues to know when their patients are not understanding something, and that goes back to teaching basic communication skills and then learning other skills such as teach-back that allow the young health professional to find out that they have not been communicating clearly. Schuster noted that teaching students and residents how to use a translator is important because doing so stresses the importance of communicating clearly and using health literacy skills.

Sabrina Kurtz-Rossi, assistant professor of public health and community medicine and director of the Health Literacy Leadership Institute at Tufts University School of Medicine, said that she teaches an inter-professional course to dental, nutrition, and pre-med students and asked if all of the health professions have written health literacy standards and if these are getting incorporated into the various health professional schools. Schuster and Robinson both noted that getting standards written and incorporated into curricula takes champions with enough gravitas to get difficult and complex work done. Rima Rudd remarked that it might be possible to establish a dialog among the health professions to get one or two competencies as a starting point with which every professional organization would abide. One place to start, she offered, would be the use of plain language followed by teach-back.

Isham commented that the continued professionalization in health care and the resulting fragmentation of training and self-organization of professions in different silos has created a problem around consistency, particularly when those professionals then need to work together as part of a health care team. It also creates an opportunity, though, for those organizations to make demands of what they need in terms of prepared professionals.