Given the dynamism, complexity, and context-dependency of childhood obesity etiology, it is difficult to translate research results, especially findings from animal experiments, into real-world application. In Session 4, moderated by Debra Haire-Joshu of Washington University in St. Louis, the speakers explored in detail some of the challenges—as well as the opportunities—for real-world application of research into childhood obesity. This chapter summarizes the Session 4 presentations and discussion.

According to Aryeh Stein of Emory University, the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944–1945, which Karen Lillycrop had briefly mentioned in her earlier presentation, has long been recognized by researchers as a useful period for studying the effects of short-term hunger on subsequent generations. Stein summarized evidence from those and other studies on “real-world” human prenatal exposure to famine and its effects on obesity-related outcomes. In addition to the Dutch Hunger Winter and other periods of famine during World War II, researchers have examined next-generation obesity-related outcomes of the China famine of 1959–1961 and the Biafra, Nigeria, famine of 1967–1970. Stein emphasized that all of the studies he surveyed are flawed by fundamental confounding factors, the main one being that women become amenorrheic when food is restricted, so fertility drops, making it impossible to know how children born to fertile women are different from those who would have been born if fertility had not dropped. Additionally, none of the studies can separate the effects of hunger from the effects of other stressors, such as the extremely cold temperatures of the

Dutch Hunger Winter. That said, Stein observed two general conclusions: (1) female offspring appear to be more vulnerable to prenatal exposure than male offspring, and (2) gestational exposure appears to have a greater effect than later exposure.

Following Stein’s presentation, the focus of the workshop shifted to the social, health policy, and clinical implications of the wide range of animal and human evidence being discussed. Sarah Richardson of Harvard University explored the implications for women, particularly poor women of color, of the focus on female reproductive bodies as the central site of obesity-related epigenetic programming. She expressed concern that unless some critical issues are attended to, the public discourse around epigenetics and obesity is likely to become deterministic and stigmatizing in a way that threatens women’s reproductive autonomy. When communicating about epigenetic science in the public sphere, she urged greater emphasis on the complexity of the science, differences between animal and human studies, the role of paternal as well as maternal effects, and the need to seek societal changes rather than individual solutions.

In his discussion of the role of scientific evidence in Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) health policy development and implementation, Matthew Gillman of the Harvard School of Public Health agreed with Stein that obesity prevention calls for a greater focus on the environment and policy and less emphasis on the individual. He emphasized the importance of evidence in policy decision making and identified ways to improve DOHaD etiological evidence from both animal and human studies. He urged researchers who rely on animal models to harmonize experimental designs and measures and to report more null results. He suggested that more innovative experimental designs and analyses and more comparing and contrasting across studies could help overcome the confounding limitations of human observational research. He also discussed how prediction models, risk–benefit and intervention studies, long-term simulation modeling, and natural evaluation experiments can help inform DOHaD policy.

Finally, Shari Barkin of the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University brought the discussion full circle by reiterating what Sandra Hassink had emphasized in her opening remarks, that is, the clinic setting is a ripe environment for implementing childhood obesity interventions. The challenge is, how? Based on recent research, Barkin identified several potential clinical interventions for improving offspring obesity and metabolic dysfunction outcomes. For example, evidence suggests that maternal poor nutrition during pregnancy combined with rapid infant catch-up growth leads to increased metabolic dysfunction in offspring. A potential clinical application of this knowledge is the promotion of appetite regulation during infancy. But again, how? One of the objectives of the Greenlight Intervention Study, Barkin said, is to develop methods for

training providers to teach parents how to recognize hunger and satiety cues in their infants and how to soothe infants in ways that do not involve only feeding. Based on results from that and many other studies, Barkin suggested several interventions that could be implemented in the pediatric clinic, such as providing group visits or health coaching calls to pregnant women and setting nutrition and activity goals for parents as well as for toddlers.

PRENATAL EXPOSURE TO UNDER-NUTRITION AND OBESITY RISK IN ADULTHOOD1

Aryeh Stein of Emory University reviewed the current scientific literature on prenatal exposures to famine and food shortages and their effects on adult body weight and obesity risk. He used as his starting point a review study coauthored by him and L. H. Lumey of Columbia University (Lumey et al., 2011). For this workshop presentation, his research assistant, Bernice Thomas, supplemented the Lumey et al. (2011) findings with a PubMed search. The search yielded 11 relevant studies covering 3 famines or periods of famine: (1) World War II, (2) China, and (3) Biafra. Stein did not conduct a formal meta-analysis, but rather he reviewed some of the central themes across the 11 studies.

Famines of World War II

The most famous famine episode of World War II was the Dutch Hunger Winter, a 5-month period of food shortages during the last winter of the war (1944–1945). According to Stein, the Dutch Hunger Winter has long been recognized as a great period for studying the short-term effects of famine and food deprivation on the next generation. First among those studies was Ravelli et al.’s (1976) analysis of the medical examination data of 19-year-old males born during the famine who were categorized as being either exposed or unexposed to the famine based on where in Holland they were born. Individuals born in the urban areas of western Holland were considered exposed. Those born outside those areas were considered unexposed. Individuals were also grouped according to the timing of exposure during gestation. The authors reported that individuals exposed during early and middle gestation had an increased prevalence of obesity at age 19 compared to individuals born in unaffected areas and that individuals exposed during very late gestation had a lower prevalence of obesity compared to individuals born in unaffected areas (i.e., obesity as defined

______________

1 This section summarizes information and opinions presented by Aryeh Stein, M.P.H., Ph.D., Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

by 120 percent of the standard set at the time by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company). Stein pointed out that the increased prevalence of obesity among 19-year-old males exposed to famine during early or middle gestation was a doubling (from 1 percent to 1.9 percent). However, according to Stein, Lumey has access to the original data, and he replicated the analysis using more current standards of obesity—that is, BMI—and found no differences in BMI among the groups.

The Ravelli et al. (1976) study was a retrospective cross-sectional sample of 19-year-olds. Stein’s literature search yielded two relevant Dutch Hunger Winter studies, both of which used prospective birth cohort approaches. The first, Ravelli et al. (1999), followed a group of men and women born in the main Amsterdam maternity hospital up through the age of 50. The study included a total of 741 men and women, 298 of whom were exposed to the famine at some period of gestation. The data were stratified by early, middle, and late exposure in non-overlapping cohorts and were further stratified by gender. The researchers reported that women exposed to famine during early gestation were 7.9 kilograms heavier than unexposed women, representing a 7.4 percent increase in BMI. They reported no detectable differences in men.

Stein’s research group independently replicated the Ravelli et al. (1999) study a few years later among what were then 59-year-olds (Stein et al., 2007). They included in their analysis three additional birth institutions, including two maternity hospitals and one midwife training school. The study included a total of 956 individuals, 350 of whom were exposed to the famine at some period of gestation. They stratified the data into four partially overlapping gestational exposure periods. They were unable to replicate the large increase in body weight in the early gestational group. Instead, they found a consistent 4 percent kilogram increase among women exposed to famine at any time during gestation relative to the unexposed controls. They found no evidence of any effect in men except in men exposed very early in pregnancy. Stein reminded his audience that sexual differentiation in humans occurs in the first few weeks of gestation.

In addition to the Dutch Hunger Winter, the Leningrad siege of 1941–1944 has also been studied for its association with adult body weight. Stanner et al. (1997) collected data among survivors of the siege who were recruited in and around Leningrad in the 1990s, with an average age of 52 years. The authors grouped the recruits into one of three groups: (1) those born in the siege area (i.e., German-occupied areas of Leningrad) before the siege, (2) those born in the siege area during the siege, and (3) those born outside the siege area. They were unable to identify any differences in BMI among the three groups. They reported a somewhat lower skin fold ratio in women in the unexposed group compared to the other two groups.

Finally, Stein identified a fourth relevant World War II study pub-

lished in the Israel Medical Association Journal (Bercovich et al., 2014) on individuals born in Nazi-occupied parts of Europe during the war and therefore whose mothers could be assumed to have been exposed to food restrictions as well as other stresses associated with being Jewish in German Europe. Stein referred to the sampling of exposed individuals as “snowball sampling” among individuals living in Israel and known to be Holocaust survivors by Holocaust survivors’ organizations. The control group included individuals from the Israel National Health Interview Study. It was a small study, Stein said, with 70 individuals in the exposed group and 230 individuals in the control group. The mean age at assessment was 69 years. The researchers reported a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia, diabetes, and hypertension in the exposed group, compared to the unexposed group, and about a two-unit increase in BMI among males in the exposed group compared to males in the unexposed group (i.e., 29.1 in the exposed group compared to 27.0 in the unexposed). They reported no difference in BMI for females.

China Famine, 1959–1961

There have been several studies of the long-term consequences of being born during the 2-year China famine of 1959–1961. In Stein’s opinion, probably one of the best is Huang et al. (2010). The authors used a variety of approaches to try to model the deficit in population count attributable to infertility during the famine by examining how urban versus rural areas fared. Both areas suffered famines, but because mass shipments of food were sent from rural to urban areas, rural areas suffered a more severe famine. The researchers reported that individuals born before the famine had higher BMIs than individuals born after the famine, but that individuals born during the famine had lower BMIs than individuals born after the famine. Stein pointed out that the famine caused perhaps 50 million deaths, most of which were children, and that one of the limitations of the study is that it did not account for differences between the children who died during the famine versus those who survived and became part of the study sample.

In a second study of the China famine, Yang et al. (2008) reported a significantly higher BMI among women in three different famine groups (born in 1959, 1960, or 1961) compared to control women born in 1964. A limitation of that study, Stein pointed out, was uncontrollable confounding by age, that is, as people age they tend to put on weight.

In another study, Wang et al. (2010) examined individuals at approximately 50 years of age who were born before the famine (the toddler group), during the famine (gestational), or after the famine (controls). They reported that among women, but not men, those born before the famine had a more pronounced odds ratio for overweight (1.48) than those born

during the famine (1.26) and a significantly greater odds ratio for obesity (1.46) than those born after the famine. The authors reported no significant differences in men.

In a fourth study of the China famine, Wang et al. (2012) reported lower odds of obesity in men exposed during fetal development compared to a unexposed control group.

Biafra, Nigeria, 1967–1970

Stein found one study of the long-term effects of exposure to the Biafra famine, a consequence of the Nigerian Civil War in the 1970s. Hult et al. (2010) conducted a house-to-house recruitment of individuals who were roughly 40 years old and then categorized the individuals by their exact age and whether they were born in the region during the famine. They reported that the unexposed, being younger (born after 1971), were thinner than the exposed. Those conceived and born during the famine had a somewhat higher BMI than the unexposed.

Addressing Questions of Selectivity

To address questions of selectivity, Stein said, van Ewijk et al. (2013) examined data from the Indonesian Family Life Survey and tried to identify individuals who may have self-selected to change their diets during Ramadan. The researchers analyzed the data based on presumed exposure to Ramadan fasting while in utero and found that Muslim individuals who were exposed to Ramadan fasting early in gestation were thinner than Muslim individuals who were not in utero during Ramadan. They found no association between non-Muslim individuals born in utero during Ramadan and either BMI or weight.

Summary of the Evidence

In summary, Stein found three relevant studies of the Dutch Hunger Winter. All three studies suggested that at least one group of individuals exposed to the famine in utero showed an increased prevalence of at least one measure of overweight later in life, with early gestation tending to have stronger associations than later gestation and with stronger associations observed in women than in men (when the researchers were able to analyze both sexes). Among the four Chinese famine studies, the results are highly divergent. It is possible to make any determination one wants, Stein said, depending on the study picked. The Leningrad study authors reported no major associations between in utero exposure to famine and later obesity risk. The Nigeria study demonstrated an increased waist circumference

and increased risk of overweight in those exposed to the famine. Finally, the Ramadan study demonstrated that those exposed to Ramadan in utero were thinner.

Conclusion

“I am an epidemiologist,” Stein said. “The first thing epidemiologists always say is, ‘The study is fundamentally flawed.’” He remarked that even his study is fundamentally flawed (Stein et al., 2007). The main reason for this, he said, is that when food is restricted, the first thing that happens to women is that they become amenorrheic. So fertility drops. In Holland, during the Dutch Hunger Winter, fertility dropped 50 percent. In China, fertility dropped 60 to 70 percent in some places. In Leningrad, fertility dropped 80 percent. If fertility drops, but some women are still having children, it is impossible to know what makes children born to those women different from the children who were not born to women who were not fertile (but who otherwise might have been born if the women were fertile). Any study that compares the general population before and after a famine to the group of individuals who conceived during the famine is fundamentally confounded by that problem, which with most experimental designs Stein described as “not resolvable.” In his opinion, his study (Stein et al., 2007) came closest to resolving that problem because he and his colleagues recruited siblings of the affected birth cohort. But none of the other studies have been able to do that, he said.

Nor have any of the famine studies been able to separate the effects of food shortages from the effects of all the other wartime stressors, such as the particularly cold temperatures of the Dutch Hunger Winter. It is impossible to know how many of the observed effects were due to the famine versus the cold temperature.

Where there are male versus female data, Stein observed that female offspring tend to be more vulnerable than male offspring. He said that the data do not lend themselves to an explanation for why that is the case.

The data also suggest that the risk of obesity is increased following early gestation exposure. But the only famine for which researchers have really been able to examine early gestation effects is the Dutch Hunger Winter. The other famines were too long to differentiate early exposure from either other periods of exposure or whole gestation exposure.

MESSAGES TO WOMEN ABOUT EPIGENETICS AND CHILDHOOD OBESITY2

Sarah Richardson of Harvard University spoke about how fetal origins research focuses on female reproductive bodies as a central site for epigenetic programing and public health policy intervention and the implications for women of this rising discourse, with a particular emphasis on the implications for poor women of color and their children. “If we do not attend to these issues,” she said, “epigenetics can become another stigmatizing, determinist discourse that threatens women’s reproductive autonomy and contributes to fat stigma and moral panic about the mothering practices of poor women of color.”

She emphasized, first, that epigenetics has a life well beyond the laboratory and the halls of the Academies. “It has riveted the public,” she said. In her opinion, it has been received in a largely celebratory manner, categorized variously by mysticism, poetic wonder, hype, and humor, with popular writing on epigenetics often projecting very nascent scientific findings into practical advice for everyday living. Epigenetics is poorly understood by the public, Richardson observed, and has generally been received in a way that mirrors the genetic determinism of previous eras by offering switches that can turn genes on and off through simple lifestyle modifications. She remarked that she has been following the trope of headlines that say, “You can change your DNA. You can change your genes.” Those headlines are a reminder, in her opinion, that there is a high degree of scientific illiteracy around both genetics and epigenetics.

Richardson observed that while the presentations at this workshop had been well balanced, much of the other discourse around epigenetics tends to convey a larger effect size and much greater confidence in the solidity of the science in humans than is reflected in the scientific literature. She remarked that part of this hype can be attributed, of course, to the ways in which maternal fetal epigenetic science speaks to urgent public health priorities in the areas of infant mortality, early childhood development, and the prevention of complex and resource-intensive public health problems, such as obesity. There is a great amount of hope that epigenetics can help to address what have been intransigent problems, presenting a rich translational context for attracting investment and interest in epigenetics research and allowing epigenetics research to circulate to much broader publics than other areas of science.

Epigenetic programming also resonates publicly, Richardson continued, because it raises philosophically riveting questions of the possibility that

______________

2 This section summarizes information and opinions presented by Sarah Richardson, M.A., Ph.D., Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts.

one’s own experiences and behaviors can amplify into future generations, connecting with traditional notions of inheritance as patrilineal and matrilineal. This intergenerational kind of claim has focused largely on females. One reason for the focus on females, Richardson explained, is that the maternal body in fetal programming types of explanations is conceptualized as an adaptive environment for the growing infant who is receiving crucial developmental cues. Because this programming can imprint on the female fetus’s own gametes, it has been suggested that the effects of the maternal environment may be intergenerationally passed through the maternal line to grand-offspring.

Historically, Richardson observed, this kind of formulation of public health risk is, on the one hand, rooted in long-standing concerns to improve society by reducing the number of problem people through the management and control of human reproduction and, in particular, by calling on mothers to raise sound and productive citizens. That movement reached its heights in the eugenic era when, using what Richardson referred to as the very new genetic science, public health officials urged that certain maternal bodies were so harmful to society that they should be called upon not to reproduce. Women in the tens of thousands were subjected to forced sterilizations, Richardson said. The effects of this were particularly harsh on women of color and had a legacy well into the 20th century—and, some would say, Richardson observed, even to this day. From that legacy came a new profound commitment to reproductive autonomy and a new humility about directing human choices through very new science.

The science of maternal fetal epigenetic programming converges with several major trends in 20th- and 21st-century science, gender, and culture, Richardson continued, from an understanding of motherhood as instinctual, selfless, and intrinsically moral to a notion of motherhood as an agential project of the self, in which the mother’s interests are often perceived to be in tension with the child’s; from a psychosocial model of human development to a genetic and neurological model of child development; and from a concept of birth as that moment of personhood and medical concern to a concept of conception and preconception as the focal points of political interests and biomedical interventions in reproduction.

Epigenetic studies of maternal effects, given this backdrop of history, raise vital social, ethical, and philosophical questions for Richardson and others. Is there a potential for this new research to heighten public health surveillance of and restrictions on pregnant women and mothers through a molecular policing of their behavior? How might this new research participate in the often troubled history of notions of the supreme role of the mother in normal and pathological development? What are the empirical and methodological implications of a research focus on maternal effects largely to the exclusion of the larger social environment and, of course, paternal effects?

In the case of claims of obesity, added to these concerns is a worry about replicating harmful stereotypes and misconceptions that contribute to stigma about fat children, which in itself can harm their mental and physical health and imperil their safety. Richardson pointed to childhood bullying issues as an example. The notion that a fat child is something to mourn and to avoid at all costs is reflected in images known as headless fatties, which, Richardson noted, appeared on a few slides at this Institute of Medicine (IOM) meeting. Such images suggest that fat is such a horrific thing that a mother and child would experience shame if their faces were shown. Critics have pointed out the profoundly dehumanizing effects of such images.

Countering this stigma is a growing and important critique of the use of the language of health and science and the concept of an obesity epidemic to tag certain bodies as a threat to the nation in ways that are often laced with the language of moral panic. Who Richardson referred to as “fat activists” and their allies are not always looking to science and medicine for help and hope and are increasingly wary of their use of health to control and limit their autonomy and contribute to fat stigma. Their view is that a world in which all bodies are accepted is the ideal one for overweight and obese people, and they wish to have maximal autonomy to live their lives as they wish.

Regarding problematic considerations of race and class, Richardson said that they do not occur only in the popular communications of the science. They also exist in the scientific literature. She highlighted an example from Jonathon Wells, who she described as an influential theorist of early developmental programming in the prenatal maternal environment who has been very interested in the prenatal development of metabolic disorders and obesity as somatic manifestations of the intergenerational transmission of health inequalities. Wells (2010) modeled how features of the mother’s social and environmental context during her own development, including her social class, may be transmitted to the growing fetus, conditioning the fetus for a life of inequality even before birth. According to Wells, Richardson explained, the maternal body serves as a transducing medium for health inequalities from one generation to another. In Wells’s model, what he calls “maternal capital,” including public health policies, education, and health care, is corporealized in the maternal–fetal relation, Richardson explained. She remarked that Wells has quite provocatively used the term “metabolic ghetto” to refer to spaces of disadvantage within the mother’s body and has argued that public health policies must target multiple interventions through the maternal medium.

While there is a huge heterogeneity in discourse in the obesity literature, some of that literature has replicated the focus on mothers as both the agential causes of undesirable outcomes and the point of intervention. In fact,

the focus extends not just to mothers, but to all women, even beginning at birth or, according to Wells’s words, the total developmental period of mothers (Wells, 2007). For example, Kuzawa (2005) suggested that “public health interventions may be most effective if focused not on the individual, but on the matriline” (p. 5). These discourses often include a representation of great responsibility combined with little agency, which Richardson referred to as the “urgent, nonspecific expansive intervention model.” She pointed out some hyped language in the literature based on this model: the “feed-forward cycle of maternal to offspring obesity transfer,” the “importance of addressing the risk of obesity before females enter the childbearing years,” and “intervention during pregnancy merits consideration” (Olson, 2007, p. 435).

The Maternal Body as an Epigenetic Vector

Richardson has argued in some of her writing on maternal fetal epigenetics that in scientific research the maternal body emerges as an epigenetic vector—an intensified space for the introduction of epigenetic perturbations in development. She discussed some of the ways that this notion is being mobilized in public discourse around the research findings.

First, she referred to what she called a “deficit model,” with the research principally advancing, or being seen as advancing, a model of epigenetic modifications as a source of error, adverse effects, or disease risk. So while scientists acknowledge that epigenetics may provide a route to human enhancement or therapy, the main body of work at this time—and the central object of concern—is how to prevent the adverse effects of impaired or maladaptive maternal environments that are seen as causing epigenetic lesions in human lineages.

Second, maternal bodies are regarded as the central targets of epigenetics-based health intervention. Graphically, time and time again, a mother’s body is shown at the center of a causal scheme or scheme of intervention, with public health interventions being seen as most effective if they target women. Again, Richardson noted, what counts as a maternal body in this literature is potentially quite large and includes all premenopausal women, including young girls. She remarked that the point had been made repeatedly at this workshop that paternal effects have been neglected. Richardson observed that males of many species provide paternal care. Male gametes, as Stephen Krawetz discussed in his presentation (see Chapter 3), are also subject to environmental exposures and may carry critical developmental cues to future generations. While paternal effects are increasingly being recognized by scientists, with several studies substantiating the existence of intergenerational effects in mammalian paternal lines, Richardson said that it is fair to say that there is an overwhelming focus on

maternal effects in the research literature. She noted that in the highly cited Zhang and Meaney (2010) review article, the term “maternal” or “mother” was used 137 times, the term “parental” or “parent” 11 times, and the term “paternal” or “father” only three times.

While one can defend this imbalance by arguing that maternal phenotype has a greater capacity to shape offspring phenotype, in Richardson’s opinion, that argument is largely a working assumption rather that something that has been fully validated. As a cultural study scholar and historian, she also pointed to the fact that despite evidence that paternal behaviors and life experience, such as alcohol use, smoking, and pesticide exposure, can impact the health of offspring from conception and over time, public health interventions to reduce fetal harm have historically consistently focused on the mother and minimized paternal effects. This asymmetry, she said, originates in long-standing Western cultural and ideological convictions that include, on the one hand, a belief in the greater vulnerability of female rather than male bodies, and, on the other hand, a belief in the primary responsibility of the mother for child development and resistance to notions of male reproductive vulnerability and paternal responsibility for the development of embryos and infants.

Third, while the target of intervention is the maternal body, the desired outcome of epigenetics-driven health interventions is usually improved fetal health. Researchers, of course, do hope that a collateral effect of their policies will be to enhance resources for pregnant women. However, most proposed interventions are directed toward the most efficient methods to ensure developmentally optimum outcomes for the fetus. Richardson commented that symbols favored by some of the major texts and societies represent this, with fetuses encapsulated in headless, legless maternal abdomens. She pointed to insignia of the International Society for Developmental Origins of Health and Disease and the cover of one of the field’s leading textbooks (Gluckman and Hanson, 2004) as examples. The maternal body in this discourse is a transducing and amplifying medium necessary to get to the fetus—an obligatory passage point, not a primary end point or subject of the research.

Finally, while maternal bodies are conceptualized as having great power to influence future generations and are positioned at the center of the intervention model advanced by many in the field, in fact the model accords individual women very little power to influence their own outcomes. Richardson considered this an interesting feature of these kinds of feed-forward or mismatched models. While women are instructed to do all they can to prevent harm to their fetus, at the same time, with the epigenetic feed-forward cycle hypothesized by maternal fetal effects research, adverse effects originate in a misalignment between a fetus’s initial epigenetic programming and eventual environment. So the system has this kind of inertial

quality, Richardson said, where short-term investments may not lead to long-term benefits that are beyond conscious or individual control. The fact that change manifests at the level of intergenerational lineage, rather than the individual female, advances a shifting and mixed message regarding maternal agency and responsibility. In Richardson’s opinion, the system exhorts mothers to make changes that are unlikely to bring them or their offspring benefit. At the same time, it produces a model of the maternal body that suggests that maternal experiences, exposures, and behaviors may have very significant amplified consequences for the woman’s offspring, her descendants, and society at large.

Conclusion

In wrapping up, Richardson reiterated that epigenetic research on maternal effects advances a model of human inheritance and development in which the wider social and physical environment can be seen as heritable and as a determinant of future biomedical outcomes via discreet biochemical modifications introduced by the amplifying vector of the maternal body. She stated that while the hope is that this literature would move the field away from forms of deterministic explanations, in fact the language strongly resembles that of genetic determinism. The multivalenced concept of a vector points to a causal mechanistic explanatory landscape in which genes remain very much at the center, with environments, nutritional factors, toxins, social policy, and stress all collapsed into molecular mechanisms acting at the level of the DNA. Rather than challenging genetic determinism and biological reductionism, Richardson suggested that present-day research programs in human epigenetics could strategically appropriate and modify the discourse to produce a new form of determinism, a somatic determinism or an epigenetic determinism, one that places the maternal–infant relation at the center.

Richardson drew attention to a research comment published in Nature in 2011 that she, Matthew Gillman, and several others in the field coauthored, where some of the issues that she discussed at the workshop are highlighted and where concrete suggestions are offered for the translation of this research into the public sphere in ways that she and her coauthors considered to be non-stigmatizing and that appropriately clarify the state of the science (Richardson et al., 2014). They made four suggestions: (1) avoid extrapolating from animal studies to humans without qualification, (2) emphasize the role of both paternal and maternal effects, (3) convey complexity, and (4) recognize the need for societal changes rather than individual solutions. Richardson expressed concern that too often there is an impulse to simplify in order to quickly move scientific findings into the public sphere. When that happens, many of the efforts outlined in her suggestions are neglected: differences between animal and human

data are not clarified, the role of both paternal and maternal effects are not emphasized, and the complexity of the findings are not conveyed (e.g., that an effect size is small or that there are many still poorly understood factors at play). She emphasized that focusing on societal-level changes, instead of instructing individuals to change their behavior under conditions of structural inequality, would be best for everyone involved and also for addressing issues of stigma.

Matthew Gillman of the Harvard School of Public Health began his presentation by expressing gratitude to, among others, David Barker, “without whom,” he said, “none of us would be here” (Gillman and Jaddoe, 2013). He also showed what he said would be his “only slide on theory,” that is, that earlier intervention, during developmental periods of plasticity, sets individuals on better lifetime health trajectories than later intervention does (Godfrey et al., 2010). For the remainder of his talk, he discussed ways to improve the evidence base for Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) health policy.

Impact of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease and Health Policy

Gillman described health policy as strategies to improve health via government actions at the national, state, or local level through legislative or regulatory means. Health care policy is a subset of health policy that is aimed at improving individuals’ health via the organization, financing, and delivery of medical care services. Because pregnant women and infants see medical providers for routine care more often than they do in any other period in the life course, health care policy is a key piece of DOHaD health policy. Examples of DOHaD health policies are Massachusetts’s regulation of child care centers requiring each child to participate in at least 60 minutes of physical activity daily and baby-friendly hospital initiatives to promote breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity, or to screen and provide treatment recommendations for gestational diabetes. Gillman explained that DOHaD health policies also include government policies, such as cigarette tax policies that reduce smoking both outside of and during pregnancy, and mixtures of government and health care policies such as the IOM guidelines for gestational weight gain, which could be transmitted either through health care or outside of health care.

______________

3 This section summarizes information and opinions presented by Matthew Gillman, M.D., S.M., Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

The role of evidence in health policy is to both develop and evaluate policies, Gillman remarked. While evidence is only one of several factors that drive policy decisions, he said, “If we have the wrong evidence or the wrong type of evidence, we might be outside the loop.” Ideally, Gillman said, evidence is at the center of decision making, as it for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF, 2009). The question for him is, “How can we have the best types of evidence to drive policy?”

Although improving DOHaD evidence for use in policy development begins with etiology, which Gillman noted was the subject of most of this workshop discussion, it can also involve prediction, risk–benefit analysis, interventions, long-term effects, and policy evaluation. Gillman discussed each of these types of policy-relevant evidence in turn.

Etiology

While animal experiments have provided very helpful information on exposures, timing, mechanisms, and effects on outcomes, and while they have effectively, in Gillman’s opinion, “proved the programming principle,” they could be more helpful. What is often missing, he said, are certain features of randomized controlled trials in humans, including specification of the source population, a sampling frame and eligibility criteria, recruitment and retention rates, blinding, intention to treat analyses, attention to missing data, and cluster methods for litter sizes greater than one (Muhlhausler et al., 2013).

Ainge et al. (2011) attempted a systematic review of rodent models of maternal high-fat feeding and offspring glycemic control but, Gillman said, they were unable to summarize or meta-analyze the data because of the low quality and variability among the studies. Starting with 1,483 studies, they identified only 11 that met their criteria. Among those 11, quality scores were low, and there was a large amount of variability in maternal diet, with some being hypocaloric, others hypercaloric, others not stated, and none isocaloric, and a wide range of fat and carbohydrate content. Additionally, there was large variability in postnatal feeding regimens and age at outcome assessment.

Another way that animal studies could be more helpful, Gillman said, is by following, not just leading, epidemiology. In particular, he suggested that animal studies follow epidemiology’s lead in addressing pre-pregnancy obesity, gestational weight gain, low-carbohydrate and high-protein diets, glycemic index or load, vitamin D, and smoking. In his opinion, it would be great to have all of these translated into animal models.

In sum, animal experiments would, in Gillman’s view, be greatly improved by more harmonizing of interventions and measures across studies and by “translating up.” He also encouraged the publishing of null results.

Gillman reminded the workshop audience that DOHaD is an interdisciplinary field with multidirectional communication among several different fields, with evidence deriving from population-based studies, animal models, in vitro studies, and clinical studies. Just as there is room for improvement in animal models, the same is true of population-based studies. Both observational studies and randomized controlled trials have a number of disadvantages. In Gillman’s opinion, confounding is the main disadvantage of observational studies. In fact, the main reason randomized controlled trials are conducted is to minimize confounding. There are a number of what Gillman called “epidemiological tricks of the trade” to manage confounding. He noted that his list of innovative study designs or analyses was very similar to Caroline Relton’s list (see Chapter 3 for a summary of Relton’s presentation): judicious multivariable analysis, sibling-pair design, cohorts with different confounding structures, comparing maternal versus paternal effects, long-term follow-up of randomized controlled trials, Mendelian randomization, the use of biomarkers, and quasi-experimental studies (which Gillman noted are not really cohort studies, but usually repeated cross-sectional studies). Each of these has its own strengths and weaknesses. Gillman stressed that it is the totality of evidence that should be judged when using evidence to develop policy.

As an example of judging the totality of evidence, in 2011 Gillman was asked to write an editorial on breastfeeding and child obesity, in which he summarized the evidence for and against the hypothesis that having been breastfed reduces the risk of obesity (Gillman, 2011). In the editorial he categorized the evidence based on type of study design: cluster randomized controlled trial of breastfeeding promotion, cohort studies of mostly white European descent individuals, cohort studies in developing countries and in racial/ethnic minorities, sibling-pair analyses, comparisons of cohorts with different confounding structures, reverse causality studies, and studies of biological mechanisms. He identified which studies supported the hypothesis, which suggested that it may be true, and which indicated that breastfeeding does not reduce the risk of obesity. He described his conclusion as “fence-sitting.”

Gillman (2011) was published before the 11-year results of the Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial, or PROBIT, were made available. PROBIT was a cluster randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus that examined baby-friendly hospital initiatives versus usual care in 31 maternity hospitals and affiliated pediatric practices. The results of that trial indicated that breastfeeding promotion did not reduce adiposity at age 11.5 years. If anything, Gillman noted, the relative risks for the intervention sites, compared to the control sites, were above 1, not below 1 (Martin et al., 2013). The PROBIT study, Gillman said, was wonderful for a couple

of reasons, one being that it was a long-term randomized controlled trial and therefore a good test of causality.

In Gillman’s opinion, policy about breastfeeding and obesity has been based on the wrong evidence. While earlier studies suggested that breastfeeding afforded considerable protection against the risk of obesity, more recent studies, like the PROBIT study, cast doubt.

Impact of Epigenetics and Health Policy

Gillman asked how epigenetics might be translated into health policy. He explained that the conceptual model upon which the Project Viva cohort study is based is that prenatal exposures result in health outcomes mediated through epigenetics. That is, epigenetics plays an intermediate role between pre- and perinatal exposures and obesity-related outcomes. Those intermediate epigenetic biomarkers could be used as surrogate outcomes, Gillman suggested, as long as the markers are indeed causally related to the outcomes, making some studies more feasible because pregnant women and their children would not need to be followed in the long term. Additionally, if epigenetic biomarkers are causally related to outcomes, for Gillman, they serve as a rationale for what he called primordial prevention. That is, if certain pre- and perinatal factors are related to epigenetic markers that themselves are related to certain outcomes, the question for Gillman then becomes, “How can we prevent those pre- and perinatal risk factors in the beginning?” In a recently published editorial on primordial prevention of cardiovascular disease, Gillman wrote about optimizing the socio-behavioral milieu starting with conception, or even preconception, as a way to avoid exposures known to be related to offspring obesity, such as maternal obesity, excess gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes, and smoking (Gillman, 2015).

For Gillman, epigenetics is a reminder that, quoting Hertzman and Boyce (2010), “experiences get under the skin early in life in ways that affect the course of human development. . . . [E]pigenetic regulation is the best example of operating principles relevant to biological embedding [of societal influences].” Also for Gillman, epigenetics is a reminder that many solutions will not be at the individual level. Individual behavior is hard to change in restrictive environments. Instead, efforts should be aimed at changing people’s physiology or even their behavior through environmental and policy solutions. Finally, Gillman viewed epigenetics as an “easy” science to communicate to policy makers. For him, it is at what he described as the “right archaeological level” to explain how pre- and perinatal factors cause obesity. He remarked that even he understood the epigenetic differences between fat, yellow, short-lived agouti mice and lean, brown, long-

lived brown mice (see the summary of Robert Waterland’s presentation in Chapter 2 for a description).

Regarding the discussion concerning the use of epigenetic biomarkers as predictors, Gillman cautioned that prediction means separating the risk of one individual from another. It has a high bar of proof and requires a high sensitivity and specificity. A predictive signature cannot indicate a mildly elevated relative risk. Additionally, he warned that much of the talk about prediction in general revolves around the development of drugs based on what is learned about who is susceptible. Developing drugs for pregnant women and infants is, he said, “really the last thing that we want to do.”

Prediction

As an example of DOHaD prediction evidence for policy translation, Gillman described a Project Viva study on the risk of obesity at age 7 to 10 years that he and a coworker performed (Gillman and Ludwig, 2013). This study found that the optimal levels of four potentially causal and modifiable pre- and perinatal risk factors (smoking, gestational weight gain, breastfeeding, and sleep duration in infancy) were associated with a 4 percent predictive probability of obesity. At adverse levels of all four risks, the predictive probability was 28 percent. The population attributable risk (PAR) percentage (the proportion of disease incidence in a population that would be eliminated if exposure was eliminated) was 20 to 50 percent. In other words, eliminating the risks would eliminate 20 to 50 percent of the observed obesity. These results suggested to Gillman that multiple risk factor interventions in early developmental periods hold promise for preventing obesity and its consequences. Prediction studies can also be used to quantify the overall potential benefit of intervening early and to distinguish the most important determinants, which may vary by population or subgroup.

Risk–Benefit Analysis

Risk–benefit analysis provides a way to take into account different exposures and outcomes among populations. For example, it has been used to determine optimal gestational weight gain by taking into account both short- and long-term outcomes for both the mother and child. Associations between gestational weight gain and different outcomes vary. For example, the association with preterm delivery is U-shaped, whereas the association with small for gestational age is indirect and the associations with large for gestational age, postpartum weight retention, and child obesity are all direct. Oken et al. (2009) examined the average probability of all five outcomes and, based on all five outcomes, determined risk curves for

obese, overweight, and normal-weight women. They concluded that optimal weight gain lies at the nadir of each risk curve (i.e., with gestational weight gain on the x-axis and average predicted probability of adverse outcome on the y-axis).

Risk–benefit analysis has also been used to tease apart multiple outcomes among both mother and child associated with rapid weight gain during infancy. While rapid weight gain in infancy is known to be related to later obesity, it may also be beneficial for neurodevelopment. Belfort and Gillman (2013) summarized the evidence for differing effects of rapid infant weight gain on obesity and neurodevelopment, depending on gestational age, and they reported some positive associations, some evidence of no association, and insufficient evidence for some associations.

Interventions

Many DOHaD intervention studies focus on efficacy. But for policy translation, Gillman encouraged researchers to move beyond efficacy and focus more on implementation. He listed some prevention interventions that the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute’s Obesity Prevention Program has been involved with, many of which are cluster randomized controlled trials. Cluster randomized controlled trials can be very useful, in his opinion, because they focus on groups, not individuals. The features of the interventions vary. For example, one relies on health information technology, another is based on a chronic care model, yet another invokes interventions within an integrated clinical and child care system. Despite the variation in features, most are based on only one or a few kinds of determinants or one or a few kinds of settings.

In Gillman’s opinion, the “most bang for the buck” obesity prevention intervention will likely come from a whole-of-community approach, one that focuses not only on families and individuals, but also on the environment and policy (IOM, 2005). He said that he is excited about a whole-of-community project he is coleading with Ross Hammond at the Brookings Institution. The project, known as COMPACT, is aimed at obesity prevention from birth to 5 years of age: what works, for whom, and under what circumstances? At the time of this workshop, the research team had completed two intervention studies, one in the United States and the other in Australia, and had a cluster randomized controlled trial under way in Australia. The team will be using the results to design a new obesity prevention intervention for children in the United States under the age of 5 years.

Long-Term Effects

Long-term effects of interest to policy makers include effectiveness, safety, costs, and cost-effectiveness. The only way to integrate such data from multiple sources, Gillman said, is via simulation modeling. But there has not been much DOHaD simulation modeling. Instead, as an example, Gillman pointed to a study on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of blood pressure screening in adolescents (Wang et al., 2011). The researchers used a two-stage model structure. One stage was based on available data from blood pressure tracking, screening, and treatment among 15- to 35-year-olds. The other involved use of an existing coronary heart disease policy model for individuals aged 35 to death to estimate costs and effects of blood pressure screening. The researchers applied their two-stage model to the U.S. population of 15-year-old adolescents in 2000 and compared several blood pressure screen-and-treat programs versus population-wide strategies and concluded that population-wide policy approaches, including salt reduction and an increase in either physical education classes or individual exercise programs, were more effective and less costly than any of the screen-and-treat strategies. Gillman interpreted these results to mean that shifting a distribution of risk factors by a small amount over an entire population can do just as much for prevention as screening and intervening on a high-risk population.

Policy Evaluation

Gillman provided two examples of natural policy evaluation experiments. The first was a Project Viva time-series analysis of fish intake among pregnant women following warnings to eat less fish that was known to have high levels of mercury (Oken et al., 2003). The researchers demonstrated that fish intake had gradually increased before the warning, then dropped noticeably immediately after the warning, and declined steadily in the subsequent year. The analysis showed that even a weak intervention, in this case a policy promulgated through obstetricians’ offices and without a great implementation strategy, can have an effect on pregnant women’s eating habits. In Gillman’s opinion, the findings also suggested that pregnant women are concerned about their growing fetuses and may be willing to change behaviors that they might not be willing to change at other times in their lives.

A second example was Hawkins et al.’s (2014) use of a quasi-experimental approach to analyze tobacco control policies and birth outcomes. Analyzing repeated cross-sections of U.S. natality files from 28 states, they found that increases in cigarette tax were associated with improved health outcomes related to smoking among the highest-risk moth-

ers and infants. Gillman said, “Considering that states increase cigarette taxes for other reasons, not to improve birth outcomes, this is a very good side effect of this policy.”

Conclusion

In summary, to strengthen etiological evidence for policy translation, Gillman encouraged more consistent methods and harmonization of designs and measures in animal studies and more innovative designs and analyses in human observational and intervention studies. He also encouraged greater comparing and combining across human studies. In his opinion, epigenetics should help with science-to-policy communication of the results of human studies. In addition to etiological studies, several other types of studies can produce policy-relevant evidence. Prediction models can help to identify potential intervention targets; risk–benefit analyses can help inform guidelines; intervention studies that look beyond efficacy to implementation can be helpful; long-term simulation models that include cost-effectiveness can play a large part; and evaluations can be used to measure the impact of current policies.

In closing, Gillman emphasized that racial and ethnic disparities in childhood adiposity and obesity are determined by factors operating in infancy and early childhood and that changing risk factors early in life has great potential to reduce obesity disparities (Taveras et al., 2013).

If scientists know the effects of what happens in utero and early in life, such as that excess gestational weight gain and rapid infant weight gain in the first 6 months of life place a child at greater risk for insulin resistance, hypertension, and obesity, then for Shari Barkin of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, the key question is, how can clinicians apply that knowledge in their practices? Barkin elaborated on ways to apply science discussed at the workshop to clinical practice, given caveats about the context and population specificity of much of the evidence. She considered potential applications of the science based on developmental period (i.e., what happens during pregnancy versus infancy versus toddlerhood). In addition to highlighting evidence where it exists, she presented additional ideas that have yet to be tested but that she thinks should be considered.

______________

4 This section summarizes information and opinions presented by Shari Barkin, M.D., M.S.H.S., Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee.

From Science to Clinical Application: Pregnancy

Scientists know that offspring exposed to both under- and over-nourished mothers during gestation have similar metabolic dysfunction, including not just obesity but also insulin and leptin resistance. Given this knowledge, it would make sense, in Barkin’s opinion, to set clear and balanced nutritional patterns early in life, maintain those patterns during pregnancy, and reinforce them consistently in clinical settings both prior to and during pregnancy. Considering what is known about epigenetic paternal effects (see the summary of Stephen Krawetz’s presentation in Chapter 3), pediatricians should be talking to boys about nutrition. Talking with pregnant women and other family members about nutrition can occur in multiple settings, not just in the obstetrician’s office.

Scientific evidence also indicates that regardless of whether BMI changes as a result, exercise is beneficial to health and exercise during pregnancy can mitigate the development of metabolic dysfunction. A potential clinical application of this knowledge is to encourage mild to moderate exercise daily, for example, by recommending exercising or, in the case of children, playing for 30 minutes per day. Barkin commented that, given her experience as chief of the Division of General Pediatrics at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, where she and her staff see some 42,000 outpatient visits and supervise about 5,000 births yearly, while nothing is as straightforward as telling someone during a visit to exercise 30 minutes per day and that doing so will offer a greater health benefit than anything else would, simply conveying knowledge is not likely to change behavior. For most of their patients, Barkin said, “It is not about knowledge. Knowledge is necessary, but not sufficient. It is about skills and context.”

Barkin stated that there have been many pregnancy interventions aimed at educating women during pregnancy about physical activity and nutrition. They vary in approach and in how information is delivered. For example, some are group sessions, others individualized. Some health calls or coaching sessions are with a trusted adviser, others with someone unknown who is a part of an insurance plan. The interventions also vary in dose (how many) and timing (when).

With all of this variability as a caveat, Barkin highlighted two pregnancy interventions focused on physical activity and nutrition education during pregnancy. First was the Behaviors Affecting Baby and You (B.A.B.Y.) study. The participants, 110 prenatal care women, 60 percent Hispanic, were randomized during the second trimester into either a 12-week exercise intervention arm or a health and wellness arm (Chasan-Taber et al., 2011). For the exercise intervention group, researchers matched participants’ physical activity goals with their willingness to exercise, with the overall goal being to increase time spent in moderate activity by 10 percent each week until,

ultimately, participants were exercising 30 minutes on 5 or more days. The intervention involved one face-to-face visit, weekly mailed surveys and individually tailored reports, and 12 weekly telephone calls providing motivational-based individualized feedback. Barkin explained that with motivational interviewing, the interviewer does not always know the interviewee’s context, and therefore even though the interviewer is conveying expertise and knowledge, if that knowledge does not meet with any agency, the interview is unlikely to change behavior. This study took that into account as part of the study design, said Barkin. The researchers measured outcomes using a pregnancy physical activity questionnaire. They found that the exercise arm experienced a smaller decrease in physical activity in the second trimester compared to the control arm. Barkin said, “Sometimes we are talking about how to get more. Perhaps just getting to ‘better’ can affect outcomes, especially if you see patterns of decreasing physical activity during pregnancy.”

Barkin highlighted centering pregnancy as a second example of a pregnancy intervention focused on physical activity and nutrition education. She noted that centering pregnancy has been around for quite a long time and serves as a national model of group prenatal care. Applying adult learning theories that highlight the importance of group work and participatory process, it involves bringing together groups of 8 to 12 pregnant women at similar gestational ages to meet 10 times over 6 months, with the meetings facilitated by a nurse practitioner or midwife, and usually the same facilitator over time to ensure continuity. The meetings are 2-hour sessions covering nutrition and activity, stress reduction, relationships, and parenting. Picklesimer et al. (2012) showed that participation, which the researchers defined as attending even just one group session, led to a consistent reduction in preterm birth. In another recent study, Benediktsson et al. (2013) compared women who recalled receiving information during a centering pregnancy meeting to women who recalled receiving information during a typical prenatal visit. They found that recall for information about nutrition, cigarette smoking and secondhand smoke, and alcohol consumption during pregnancy was statistically different between the two types of women. Multiple other evaluations of centering pregnancy are under way, according to Barkin. “Stay tuned for more details,” she said. “We are in the evolving stages of examining evidence related to this type of clinical application.”

In addition to the potential clinical applications of scientific evidence related to physical activity and nutrition during pregnancy, Barkin discussed potential applications of what is known about maternal excess gestational weight and its interaction with pre-pregnancy weight to alter early infant growth trajectories. The science suggests that clear goals for weight gain during pregnancy should be set, perhaps by utilizing group visits or health

coaches during and after pregnancy. Barkin also encouraged more focus on appropriate weight loss after pregnancy by linking to effective community weight programs.

Barkin pointed to the IOM’s release in 2009 of a report on pregnancy weight gain guidelines (IOM, 2009) and remarked that it is known that women who experience excess gestational weight gain have children with an increased risk of high BMI and high systolic blood pressure at 3 years of age.

In a study aimed at understanding how excess gestational weight gain interacts with pregnancy weight to alter early infant growth trajectories, Barkin and colleagues used linked electronic medical record data for about 500 mother–child pairs and objective measurements of infant weight (as opposed to self-reported weights) (Heerman et al., 2014). Their main finding was that the infant growth trajectory was different for women who were obese prior to pregnancy and who also had excess gestational weight gain compared to mothers who were either obese prior to pregnancy but who did not have excess gestational weight gain or had excess gestational weight gain but were not overweight prior to pregnancy. Specifically, there was a 13 percent difference in the infant weight/length ratio at 3 months of age that persisted at 1 year of age. Also of interest to Barkin and her coauthors, and something that Barkin said they are trying to replicate, was the rapid increase in the first few months of life for infant weight gain, followed by a dip, then another increase, such that by the end of the first year of life, infants born to mothers who were obese and who also had excess gestational weight gain had greater weight/length ratios than infants born to mothers who were overweight prior to pregnancy.

Barkin considered post-pregnancy weight loss a “lever point.” Ideally, if mothers could reach a healthier pre-pregnancy weight for subsequent pregnancies, the interaction that she had just described, that is, between pre-pregnancy obesity and excess gestational weight gain, would not exist. Reaching a healthier pre-pregnancy weight would also prevent the development of the pro-inflammatory state described by Jacob Friedman and other speakers (see Chapter 3 for a summary of Friedman’s presentation). Barkin suggested that the Practice-based Opportunities for Weight Reduction (POWER) trial, although not intended to test post-pregnancy weight loss, nonetheless shows what an effective weight loss program looks like and perhaps ought to be utilized for post-pregnancy weight loss (Appel et al., 2011). The trial involved six primary care practices in Baltimore and 415 obese patients, 41 percent of whom were African American and the majority women. The patients were randomized into three conditions: (1) a self-directed weight loss control group, (2) a remote support-only group (i.e., patients received remote support from health coaches), and (3) an in-person support group (i.e., patients received face-to-face group and individual support as well as phone call health coaching). What was most surprising to

the investigators, Barkin said, was that both average weight loss and the percentage of patients who lost at least 5 percent of their body weight at 24 months were similar for the two treatment groups (10.1 pounds and 38 percent, respectively, for the remote group, and 11.2 pounds and 41 percent for the in-person group, compared to 1.8 pounds and 19 percent for the controls). In other words, the treatments were clearly and similarly effective despite their different durations and doses. In Barkin’s opinion, it is important to keep in mind that different durations and doses of an intervention can have similarly effective outcomes, particularly when thinking about clinical applications. In the case of the POWER study, participants received a higher dose earlier in the trial than in the later phases, and this still resulted in clinically significant outcomes. It does not appear that the same degree of participation throughout a study is necessary, Barkin said.

In a subsequent focus group study, Bennett et al. (2014) asked providers how they would use the POWER trial results. Providers replied that their role was to refer patients to effective programs and provide endorsement, to provide patient accountability, and to cheerlead when things are going well. They viewed their role in actual weight management as limited and, instead, preferred to maintain long-term trusted relationships with their patients so that they could connect them to the appropriate programs.

From Science to Clinical Application: Infancy

Barkin identified two potential clinical applications of scientific evidence indicating that poor nutrition during pregnancy, with rapid infant catch-up growth, leads to later increased offspring adiposity, hyperphagia, and hyperinsulinemia. First is the promotion of infant appetite regulation, perhaps by training providers to discuss with parents how to recognize satiety cues. Second is a change in the pediatric paradigm for catch-up growth. She suggested that perhaps weight gain velocity in early infancy should be slowed down and the expectations of early growth for providers and parents reassessed, although more science is needed to know what a safe velocity would be with respect to unintended consequences (e.g., effect on neurodevelopment) (see previous section for a summary of Matthew Gillman’s discussion on the use cost–benefit analysis to analyze trade-offs associated with rapid infant weight gain).

As an example of the promotion of infant appetite regulation, Barkin highlighted the Greenlight Study, a health-literature, health-numerate intervention being conducted by herself and Russell Rothman and colleagues. The researchers taught residents how to talk with families about how to recognize satiety in their infants and provide soothing strategies that do not involve only feeding. The conversations started early, when an infant was 2 months old. The materials provided to families were easy to view, with

pictures illustrating ways to tell when a baby is hungry versus full. The trial had been completed at the time of this workshop and the data were being analyzed. As with the results of ongoing centering pregnancy trials, Barkin said, “Stay tuned.”

As another example, Paul et al. (2011) tested the effects of two nurse home visits, one occurring 2 to 3 weeks after birth and the other after the introduction of solids to the infant diet, on infant weight velocity. During the first home visit, or intervention, parents were instructed on how to identify hunger versus satiety cues and how to soothe their infants. During the second visit, they were taught more about hunger and satiety cues and how to handle infant rejection of healthy foods through repeated exposure. The investigators randomized 160 mother–newborn dyads into four treatment groups, with each group receiving both interventions, one or the other intervention, or neither. The researchers found that those receiving both interventions had infants with a lower weight-for-length percentile compared to those receiving just one of the interventions or neither intervention.

Other recent work conducted by Rothman and his group has shown that larger bottles tend to result in increased consumption. “This is not normal,” Barkin said. She stated that, based on her clinical setting experience, infants and toddlers used to be the prime examples of individuals who regulate themselves. They knew when they were full and would stop eating and throw or push their plate away. Today, she and other clinicians are not seeing that behavior as much. Infants and toddlers are behaving like adults, she said, eating extra servings even when full, with their hedonic drive appearing to supersede their homeostatic regulation.

From Science to Clinical Application: Toddler

The Paul et al. (2011) study raised the question for Barkin, how can the findings be applied to toddlers? Like infants, toddlers used to have very good self-regulation thermostats. But again, clinicians are not seeing that anymore. Toddlers also tend to imitate the world around them, including how others are eating and playing. Barkin suggested that two potential clinical applications of these observations are, first, to support and reinforce toddler self-regulation and, second, to set normative habits in nutrition and physical activity. Barkin emphasized the importance of focusing on the community and the role of the clinical setting in making connections to community-based programs. She also encouraged clinicians to examine emerging science on how families, not just the child, are affected by interventions. When the goal is to improve the health of the parents as well as the child, clinicians create a much different dialogue. Additionally, Barkin encouraged considering how to utilize social networks to reinforce healthy habits.

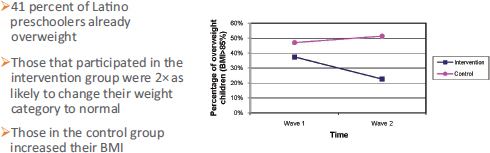

As an example of research in this area, the Salud con la Familia (Health with the Family) study tested a family-based, community-centered intervention to prevent and treat obesity among Latino parent–preschool child pairs. The study was a skills-building dyadic intervention where the focus was on improving the health for both the parents and child and helping them to use their built environment to reinforce healthy habits. The researchers found that 41 percent of Latino preschoolers were already overweight at the time of entry into the study, a prevalence that is much higher than any Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistic, Barkin said, and that those who participated in the intervention group were twice as likely to change their weight category (Barkin et al., 2012). For example, children in the intervention group who were obese at the start were twice as likely to be overweight by the end of the 3-month study, whereas the BMIs of those in the control group continued to increase even within the 3 months of the study (see Figure 5-1).

The Barkin et al. (2012) study raised the question for Barkin, why did the intervention work? To help answer that question, Gesell et al. (2012) measured both the intervention and control group social networks—not social media networks, Barkin explained, but rather bidirectional relationships through which new knowledge and new behaviors could be introduced. The researchers found that both the control and intervention groups started with some initial ties and that both groups developed additional ties over the course of the 3-month study, but the intervention treatment had been designed so that by the end of the study, the intervention group had a much more significant and dense social network.

FIGURE 5-1 Change in percentage of overweight children following a skills-building intervention where the focus was on improving health for both the parents and child and helping them to use their built environment to reinforce healthy habits.

SOURCE: Presented by Shari Barkin on February 27, 2015; modified from Barkin et al., 2012.

Summary

In summary, Barkin reiterated that the clinical setting is one of many environments that should be used to prevent childhood obesity. Ways to use it include providing more group visits and/or health coaching calls; addressing nutrition and physical activity with both pregnant women and fathers (in all clinic settings); linking to effective programs for postpartum weight loss to better prepare women for a next pregnancy; teaching parents about satiety versus hunger cues and about soothing approaches that can be used during early infancy; reassessing recommendations for appropriate weight gain during infancy and rethinking catch-up growth parameters for infants who are premature or small for gestational age; including families in setting nutrition and physical activity goals during toddlerhood for themselves and their child; and linking to trusted, effective community programs.

PANEL DISCUSSION WITH SPEAKERS

Following Shari Barkin’s presentation, a panel discussion with the speakers led to further discussion of breastfeeding and its association (or lack thereof) with the risk of offspring obesity, the famine studies, differences between animal and human studies, and calls to focus more on fetal and placental health.

Breastfeeding and Risk of Offspring Obesity

An audience member asked about breastfeeding data and what researchers know about the effects of breastfeeding on potential prevention of rapid infant weight gain and offspring metabolic dysfunction. The questioner was especially curious about the concept of dose, which Barkin had emphasized during her presentation. Specifically, what is known about exclusive versus partial breastfeeding in terms of preventing obesity and obesity-related metabolic disorders? Barkin commented on the complexities of that question, noting that bringing a baby directly to the breast, compared to bottle-feeding a baby expressed milk, not only affects the microbiome of the child in a different way but also encourages recognition of infant satiety. In her opinion good data indicate that exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months confers many benefits, such as immune globulin transference and its associations with reduced risks for cancer and type 1 diabetes. However, based on available data, in Barkin’s opinion exclusive breastfeeding does not appear to confer a protective benefit against obesity. She mentioned that in her clinic she has observed many women who use both breastfeeding and bottle-feeding and often overfeed their infants, because they find it

difficult to distinguish between satiety and hunger cues. She encouraged an assessment of that behavior.

Matthew Gillman added that in the developing world it seems that 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding is a very good recommendation. In the developed world, on the other hand, he suggested some moderation of that recommendation, specifically 4 to 6 months. Based on his team’s research results, the optimal time to introduce solid foods for obesity prevention is 4 to 6 months. He mentioned additional, emerging data from the allergy literature that also suggest that 4 to 6 months is the optimal time in Westernized countries to introduce solid foods. On the topic of infant feeding, Gillman encouraged moving the discussion beyond talking about breast versus bottle-feeding or breast versus formula feeding to talking about the different ways that people feed and other behaviors that affect infant growth trajectories and, later, metabolic function.

Famine Studies

There were several questions related to the famine studies described by Aryeh Stein. Andrea Baccarelli of the Harvard School of Public Health remarked that, much like the famine data suggest, prenatal exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals often has a more pronounced effect on females than on males, and he asked whether what he referred to as the “susceptibility window hypothesis” is enough to explain the difference. In the case of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, he said, he does not believe that it is. Stein replied that the differential susceptibility, or manifestation, of exposures seen in the two Dutch Hunger Winter studies were based on very small sample sizes in a very select population (Ravelli et al., 1999; Stein et al., 2007). During World War II, roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of all Dutch infants were delivered at home, yet the two studies that included both men and women were hospital-based prospective follow-up studies, so they represented a relatively low-risk group. He said that, yes, there is a signal, but it is unclear whether it is a strong signal.