2

Scientific and Conservation Merits of Landscape-Scale Conservation and the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives

This chapter addresses Item 1 in the committee’s statement of task: “an evaluation of the scientific merit of the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives (LCC) program and its goals.” The committee interpreted this item as asking whether a national program focused on developing a landscape approach to conservation has scientific merit, and if so, whether the LCC program has made use of current, relevant science. Therefore, this chapter reviews the development and underpinnings of conservation science with a focus on landscape scales. It also discusses modern approaches to conservation with the aim of evaluating the degree to which the LCC program has incorporated this body of work.

HISTORY OF LANDSCAPE-SCALE CONSERVATION

The United States has a long history of conserving large areas even though many 19th- and early 20th-century wildlife conservation efforts in the United States were primarily focused at relatively local scales, and undertaken by state or federal authorities or individual landowners. The committee can point to a few examples of early, large-scale conservation efforts. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 was intended to provide further protection for birds, in addition to earlier legislation that protected them from market hunting, and it was followed by the Migratory Bird Conservation Act of 1929.1 That act, according to its preamble, was

an act to more effectively meet the obligations of the United States under the Migratory Bird Treaty with Great Britain by lessening the dangers facing migratory game birds from drainage and other causes, by acquisition of areas of land and of water to furnish in perpetuity reservations for the adequate protection of such birds; and authorizing appropriations for the establishment of such areas, their maintenance and improvement, and for other purposes.

Note that this preamble expressly envisions establishing refuges in a landscape and the one threat it mentions—drainage—is a landscape-scale threat. Passage of the act led to the establishment of wildlife refuges on major flyways to protect migratory birds, an early implementation of landscape-scale conservation. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, which provided for management of grazing on public lands, also was a response to a landscape-scale threat, overgrazing on western rangelands.

Despite the above examples, many environmental threats at the time that conservation and systematic land management began continued to be perceived as local. However, many recent threats to natural resources occur at much larger spatial scales. Ecosystem degradation is occurring at an unprecedented rate due to resource extraction, urban expansion, air and water pollution, deforestation, agriculture expansion, and climatic changes. Whether it is wildfires over millions of acres, endangering human lives and property as well as economically and environmentally valuable resources, the cumulative impacts of thousands of dams disrupting natural flow regimes in large and small watersheds, the regional impacts of climate change on natural and cultural resources including people, or invasive species that alter the structure and function of entire ecosystems, it is clear that the most significant conservation challenges facing the United States today transcend administrative and geopolitical boundaries.

The scale of the conservation response does not yet match that of these threats. Scaling up conservation efforts and engaging a range of stakeholders across jurisdictions becomes necessary to muster a response proportional to the threats. Transboundary conservation also increases the capacity for finding solutions. For example, groups such as the Fire Learning Network facilitate structured learning across geopolitical boundaries primarily by establishing trust (Goldstein and Butler, 2012). This learning often brings benefits to conservation management at a local scale where conception, design, and building of local support may have been challenging without transboundary collaboration.

___________________

1 Chapter 257, approved Feb. 18, 1929, 45 Stat. 1222.

Landscape-scale conservation is not an idea only of the past few years (Turner, 1989; Dunning et al., 1992; see Box 1.1 for definition of landscape). Scientists and resource managers have long understood that important threats to natural resources operate at a landscape scale, and so effective management may require a large-scale view of systems. For example, state agencies and nongovernmental organizations have developed a landscape-scale conservation effort for the greater sage-grouse (see Appendix A). However, the fact that landscapes span jurisdictional and institutional boundaries complicates efforts to implement conservation at the landscape scale. Here, we briefly describe the recent history of federal landscape-scale conservation approaches, both to show that the LCCs are not the first attempt to address this problem and to show that effective landscape-scale management requires careful attention to institutional design. No one entity is capable of carrying out landscape-scale management by itself. By its nature, landscape-scale conservation requires partnerships or at least coordination among the entities that share authority across a landscape. These partnerships can be both difficult to create and difficult to sustain over time.

Significant federal emphasis on a landscape approach to conservation dates back at least to the mid-1980s, but it became prominent in the 1990s. The first major landscape approach to conservation for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) was the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, signed by the United States and Canada in 1986 (FWS and Environment Canada, 1986). Recognizing that cooperative harvest management efforts, which had been in place since the 1916 Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds, were inadequate to protect the continent’s waterfowl, the two nations agreed to undertake cooperative planning for habitat protection (for additional description of landscape-scale conservation at the FWS, see Chapter 5).

Enthusiasm for large-scale management efforts grew rapidly in the scientific community and among conservation practitioners (Agee and Johnson, 1989; Clark et al., 1991; Slocombe, 1993). Within a few years, spurred by a series of perceived crises under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973, regional ecosystem management had become a leading strategy in the federal conservation toolkit. The National Park Service’s National Heritage Area program was initiated 30 years ago in recognition of the need to preserve cultural resources across the nation beyond the National Park Service’s boundaries (see Chapter 6 for further discussion). Shortly after taking office, the Clinton Administration endorsed the concept (Gore, 1993). Regional plans were developed for protection of endangered species habitat in the forests of the Pacific Northwest, for restoration of the Florida Everglades, and for coastal sage scrub conservation in southern California (e.g., Frampton, 1996).

The landscape approach to conservation has been pioneered and embraced by nongovernmental organizations; community-based groups; universities; state, local, and tribal governments; and many other nonfederal actors. They have developed a variety of approaches to work across boundaries to achieve multiple objectives. The sage-grouse case study in Appendix A is a prime example. Similarly, The Nature Conservancy undertook its largest land acquisition to date with the Gray Ranch in New Mexico in 1990, and this effort evolved into a major multi-organizational landscape project known as the Malpai Borderlands Project (Sayre, 2005). By the late 1990s, The Nature Conservancy had launched scores of landscape conservation projects across the United States aiming to develop functional landscapes at multiple scales (Poiani et al., 2000). These efforts featured several common elements: all involved management beyond traditional political and institutional boundaries, emphasizing cooperation and coordination among participating entities; most focused on the production and use of needed scientific information and endorsed the concept of adaptive management, updating management strategies in light of learning over time.

CONSERVATION CHALLENGES AT THE LANDSCAPE SCALE

While the scale of conservation varies with the species and issues being considered, achieving landscape-scale conservation can be quite challenging. In part, this is because of the multiple uses that are demanded of many if not most landscapes and seascapes—to provide food, energy, water, and other goods and services for people while maintaining ecosystem functioning and biological diversity. The large area covered by most landscapes and seascapes, the complexity of the social and ecological communities within them, and the challenges of research designs provide a scientific basis for conservation (Eigenbrod et al., 2011; Baylis et al., 2015). These factors make landscape-scale conservation difficult (Lawler et al., 2014), and they require a broad scientific base that includes both natural and social sciences.

Climate change and its effects on sea level rise, on the survival of species and ecosystems, and on other aspects of human and natural systems provide challenges—but also incentives—for landscape-scale conservation efforts (e.g., NRC, 2010). The synergistic interaction of climate and land-use change (Ellis et al., 2010; Theobald, 2014) in the United States adds to the complexity of the challenge. Although anthropogenic features cover a relatively small portion of the western United States (13 percent), the human footprint disproportionately affects areas of high biodiversity such as valley floors and stream margins, further exacerbating ecosystem and wildlife management challenges (Leu et al., 2008). This may very well be an underestimate of the human footprint. For example, Forman (2000) argued that the ecological effects of roads extend outward for more than 100 meters, resulting in his estimate that about one-fifth of the U.S. land area is directly affected ecologically by public roads (see also NRC, 2005a). At the same time, land-use change, the further development of roads and other infrastructure on many landscapes, and the effects of cli-

mate change may also present opportunities for developing landscape-scale solutions.

The size and distribution of landscapes will vary by the mosaic of species, ecosystems, and human systems being considered, and by the set of relevant management concerns. For example, the greater sage-grouse (see case study on sage-grouse in Appendix A) currently occupies 56 percent of its historical range and was considered for listing under ESA, primarily because of the loss and fragmentation of its habitat (see Figure A.1), the sagebrush steppe landscape covering all or parts of 11 states. Wyoming contains 40 percent of the current greater sage-grouse population (Doherty et al., 2010) and the FWS (2010) described the greatest threats to the species as being poor grazing practices, wildfires, and agricultural conversion of sagebrush landscapes to grasslands. The threats are exacerbated by displacement from otherwise suitable habitat and functional habitat loss due to energy and other infrastructure developments. Other states that currently encompass the sage-grouse’s range have far fewer greater sage-grouse, and the primary concern for the species in the western portion of its range is loss of habitat due to wildfire and the subsequent spread of invasive plants. The other end of the spectrum of landscape size and configuration is the example of the Cheat Mountain salamander, which is only found above an elevation of about 3,000 feet within five counties in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia (Pauley, 1993). Conservation of this species depends on forest management, and 46 of the 60 known populations occur entirely within the Monongahela National Forest, simplifying protection of the species and its habitat. So the size and configuration of landscapes from both a science and conservation perspective are greatly influenced by the conservation features that are the focus of research and management attention.

INSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES OF LANDSCAPE-SCALE CONSERVATION

We have described the mismatch between jurisdictional boundaries and threats to natural resources. In addition, institutional mandates and responsibilities are divided and fragmented. Authority for conservation of natural resources has long been divided between the public and private sectors, between federal and state governments, and among individual agencies with distinct missions at both federal and state levels. Management efforts that cross these institutional boundaries inevitably face complexities and conflicts (although wisely assembled coalitions can be powerful forces for conservation).

A substantial challenge to conservation is fragmentation in land ownership. Land ownership in the United States carries with it control over the vegetation growing from the soil (except when these rights have been suspended through an alternative legal arrangement, such as easements for conservation or agriculture, or historical or cultural preservation, or when other rights, such as for mineral extraction, may affect private owners’ ability to exercise domain over vegetation on their land). By contrast, states have authority over wildlife, except for federally protected species. Native American tribes may also have or share regulatory authority on tribal lands. As a consequence, even where states have conservation responsibility for fish and wildlife, they often do not have control over their habitats.

Under the Property Clause of the U.S. Constitution, the federal government has plenary authority over the lands it owns. Since the late 19th century, the United States has used that authority to dedicate lands to a variety of purposes, encompassing both conservation and resource extraction. Beginning in the early 20th century, the United States also enacted a series of conservation statutes dealing with wildlife. Today, the states retain primary regulatory authority over most wildlife in most places, but federal regulation is primary with respect to endangered species, migratory birds, and marine mammals. In some cases, the boundaries between federal and state authority are contested.

State management of wildlife populations is not without complexity as well. States have laws giving them authority over all or most species resident within the state; all states manage fishing and hunting of resident species within their borders, although hunting of migratory birds and management of other federal trust species is done collaboratively with the FWS as allowed by federal regulation. However, many species managed by states occur over relatively large ranges covering several states. For example, the greater sage-grouse occurs in 11 western states (see Appendix A). State laws differ, sometimes significantly, in how wildlife populations are managed. Although most state agencies own or control some wildlife habitat, the vast majority of habitat supporting state-protected wildlife is managed by the aforementioned patchwork of public and private ownership. Although these differences in state wildlife laws and management do not seem to pose any threat to the greater sage-grouse itself, they do need to be taken into account in any conservation effort that includes several states.

Within the state and federal governments, conservation authority is frequently further divided or distributed among agencies with different missions. Federal authority over endangered species is divided between the FWS, which is responsible for protecting terrestrial and freshwater species, and the National Marine Fisheries Service in the U.S. Department of Commerce, which is responsible for marine species and anadromous fishes (except in Maine, where the FWS has responsibility for Atlantic salmon in freshwater). Federal land management authority is divided to varying degrees among the U.S. Forest Service in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Bureau of Land Management, the Bureau of Reclamation, the National Park Service, and the FWS in the U.S. Department of the Interior. The U.S. Department of Defense has extensive landholdings, and it

engages in conservation when feasible given that its primary mission is to ensure readiness of the nation’s military forces. (The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, in the U.S. Department of Defense, does manage and operate considerable areas around its dams, reservoirs, and dikes without a primary mission of military readiness.)

Just as importantly, conservation efforts often come into conflict with competing goals for the use of land among both private landowners and other government agencies. For example, in the arid west, water management by state agencies and by the federal Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been in significant tension with protection of endangered riparian and aquatic species for decades (e.g., NRC, 2012). State wildlife management agencies can find themselves in conflict with water and land management agencies. Even within individual agencies, there can be tensions between conservation efforts and other goals. The National Forests and Bureau of Land Management lands, for example, are managed for “multiple use,” meaning that they are used for such activities as grazing, timber, recreation, and mineral extraction. Finding the right balance among those uses is often difficult and controversial, both within the management agency and among external constituents.

Conservation efforts at the scale of large landscapes and seascapes are frequently complicated by this range of stakeholders with divergent values and mandates, and who are deeply invested in the outcome. In addition to federal and state agencies, stakeholders include environmental organizations, industry associations, nearby property owners, communities economically dependent on recreation or resource extraction, and others, including faith-based organizations (Hicks et al., 2015). These stakeholders may have a legal right to participate in decision making. Even if the law does not provide them with explicit participatory rights, they may believe their interests deserve consideration.

There is growing evidence from theory and practice that bottom-up stakeholder-driven processes are more likely to achieve long-term conservation outcomes than top-down driven ones. This evidence applies a variety of perspectives, including those interested in the growing connections of nature conservation efforts and human well-being (Milner-Gulland et al., 2014), the U.S. experience in collaborative conservation efforts and adaptive management at the landscape scale (Scarlett, 2013), a global perspective on the goals of nature conservation (Mace, 2014), and that of the scientific researcher studying stakeholder involvement in conservation (Young et al., 2013). Two recent and important examples support this observation: establishing a migration corridor for pronghorn in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem (Berger and Cain, 2014) and establishing a marine protected area network under the auspices of state legislation in California (Gleason et al., 2010).

LANDSCAPE APPROACH IN CONSERVATION

Although conservation biology has always had a strong focus on the maintenance of long-term, persistent populations of individual species, it has more recently recognized the importance of habitat conservation at larger scales, which requires a landscape-scale management approach (e.g., Sayer et al., 2013; Box 1.1). The landscape approach includes consideration of the complex jurisdictional environments, where ecological processes such as the migratory dynamics of a species, the hydrological flow regime of a river, or the spread of wildfire span many ecosystem types and geopolitical boundaries. An elk population or other migratory ungulates, for example, may spend the summer in high-elevation forest on public lands, migrate downward through a mix of public and private land, and then overwinter on private lands intensively managed for agriculture.

As scientists and managers address conservation at the landscape scale, we identify four overarching principles that need to be considered. First, there is a need to focus on both the biodiversity that occurs within these landscapes and the ecological processes and services that are derived from it. Second, species occur at different spatial scales and respond to landscapes in different manners, and these factors must be taken into account in the scientific methods used to assess the status of species. Third, science and management at landscape scales are complex and expensive, and require innovative and collaborative approaches to efficiently utilize the available resources. Fourth, which conservation features or targets are addressed (which species, communities, ecosystems, and/or processes), which threats are considered, what science is brought to bear (e.g., ecological, economic, social, and political), and how conservation and science challenges are conceptualized will have considerable influence on whether successful conservation outcomes are reached. Three key issues to consider in conceptualizing the landscape approach follow:

- Conserving biological diversity and ecosystem processes (including services) at landscape scales. Doing so requires addressing multiple spatial, temporal, and jurisdictional scales. There is no single best methodology for integrating ecosystem services into landscape conservation plans, but there is an increasing number of guidance papers, frameworks, and tools for doing so that landscape practitioners can put to use (e.g., Kareiva et al., 2011; Bagstad et al., 2013).

- Addressing landscape-scale variation for different priority issues. Different species perceive a landscape in different ways, depending on their life histories, associations with major vegetation types, and prey distributions, among other things (Fischer et al., 2005). Betts et al. (2014) proposed a species-centered approach using species-distribution models and land-cover data to measure landscapes. This variation in scale of species distribution and causes of the

-

loss and fragmentation of habitat presents a challenge for the LCC process, because each LCC was established with fixed geographic boundaries (although there is a process for adjusting boundaries;2LCC Network, 2011). The LCC boundary delineations were a result of thoughtful discussion, but it was recognized that these boundaries were context dependent. Fish boundaries often do not apply to birds, or for management of large, migratory mammals. Cultural issues do not even appear to have been part of the mapping efforts. As such, boundaries will always be somewhat problematic. To address the need for flexibility depending on the particular conservation concern, the boundaries were meant to be permeable. Any program needs to be bounded and administered through some structure (regions, districts, states, basins, etc.), but flexibility in delineating and adjusting boundaries does not need to hinder the conservation activities of the program unduly.

- Adaptive management at the landscape scale. Any program that intends to achieve conservation outcomes at the landscape scale will need to provide supporting scientific data, analyses, and tools (e.g., Curtin, 2015). Perhaps most important, these tools will need to be incorporated into an overall management approach, preferably following the principles of adaptive management. Although there are many definitions of adaptive management, two reports by the National Research Council (NRC, 2003, 2005b) discussed the concept in detail as it applies to the landscape-scale restoration of the Everglades of South Florida, distinguishing between active and passive adaptive management.

Walters and Holling (1990) defined three general ways to structure adaptive management: (1) trial-and-error, (2) active adaptive management, and (3) passive adaptive management. According to these authors, the trial-and-error or evolutionary approach (also referred to as disjointed incrementalism by Lindblom, 1968) involves haphazard choices early in system management while later choices are made from the subset of choices yielding more desirable results. Active adaptive management strategies use the available data and key interrelationships to construct a range of alternative response models (scenarios) that are used to predict short-term and long-term responses based on small- to large-scale “experiments.” The combined results of scenario development and experimentation are used by policymakers to choose among alternative management options to identify the best management strategies. Passive adaptive management is based on historical information that is used to construct a “best guess” conceptual model of the system. The management choices are based on the conceptual model with the assumption that this model is a reliable reflection of the way that the system will respond. Passive adaptive management is based on only one model of the system and monitors and adjusts, while in active adaptive management a variety of alternative hypotheses are proposed, examined experimentally, and the results applied to management decisions. (NRC, 2003)

Landscape Conservation Design (FWS, 2013a) is a landscape-scale approach to refuge system planning that is being adopted throughout the National Wildlife Refuge System and is a major objective in the LCC Network Strategic Plan (Objective 2 under Goal 1 on Conservation Strategy; LCC, 2014). The foundation of Landscape Conservation Design is the FWS Strategic Habitat Conservation Framework, which is essentially the FWS’s version of an adaptive management framework. It is quite similar in nature to the adaptive management framework of the Conservation Measures Partnership (CMP, 2013), which is increasingly being adopted as a standard by conservation organizations. Although the Strategic Habitat Conservation Framework does not explicitly mention “active adaptive management” in its use of competing models and alternative hypotheses, it clearly is designed to reflect active, rather than passive, adaptive management.

SOCIO-ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS IN LANDSCAPE CONSERVATION

Conservation science has long recognized the interdependence of people and nature (e.g., Marsh, 1864; Leopold, 1947) and the complexities of this relationship at different scales. In modern terms, society receives a variety of benefits (ecosystem services) provided by ecosystems, such as water, food, and fiber that we harvest; the regulation of climate, disease, disturbances, and the quantity and quality of water; and the aesthetic, spiritual, and recreational connections to the land and sea (MEA, 2005).

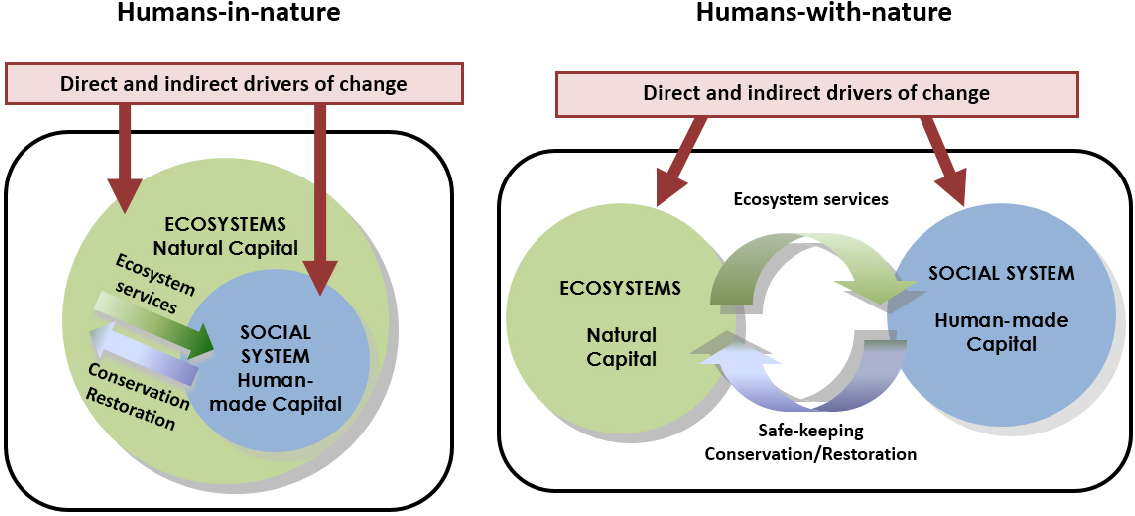

Much of the justification for landscape-scale conservation is based on an understanding of nonhuman species and their environments. However, there are equally valid reasons to invest in landscape conservation based on our understanding of how social systems work and interact with ecological systems, often referred to in combination as the socio-ecological system (see Figure 2.1). Socio-ecological systems are nested sets of social and ecological factors that interact to produce goods for society such as food, fiber, and drinking water (Berkes and Folke, 1998). Conservation planners are increasingly focusing on socio-ecological systems as they develop landscape-level conservation plans (e.g., Ban et al., 2013; Curtin, 2015).

The diversity of stakeholders who exist in any given socio-ecological system will have a considerable influence on the conservation goals and outcomes for the associated landscape. How well stakeholders are able to collaborate in working toward mutual goals will ultimately be a major factor in achieving conservation outcomes. As a result, “collaborative conservation” has become a central concept in large-landscape conservation (Margerum, 2008; Mitchell et

___________________

2 In brief, the change must be proposed by a member of the steering committee of an LCC (the “initiating LCC”), the abutting LCC(s) also must agree to the change, and then the change has to be approved by the U.S. Department of the Interior Climate Change Working Group or the LCC Council once established and operational (it was not in 2011).

SOURCE: González et al., 2008.

al., 2015). In their ground-breaking policy report on large-landscape conservation, McKinney et al. (2010) noted 10 key elements of successful collaboration. Some of the most important elements include leadership, the representation of stakeholders, how the stakeholders make decisions and govern themselves, the strategies and outcomes that are deployed by collaboration, and the ability of a collaboration of individuals and institutions to learn and adapt.

Social scientists evaluating the implementation of State Wildlife Action Plans have developed a useful conceptual model of collaboration for landscape conservation. A key underlying assumption of collaboration in landscape conservation is that it requires learning among its participants in order to be successful (Lauber et al., 2011). Three types of learning appear to be important: social (relationships and dialogue among participants), conceptual (developing new ways to define problems and think about issues), and technical (developing new means to achieve objectives).

Cultures and livelihoods are just as sensitive to landscape processes and their jurisdictional controls as are natural resources, even though they can value aspects of the landscape differently. Nonetheless, cultural conservation also can benefit from a landscape perspective. Ranching, for example, often uses different landscape units spread across public and private lands to support summer and winter grazing. Subsistence and food security of indigenous communities usually involves harvest of fish and wildlife from landscape mosaics that cross multiple management jurisdictions. Farming often depends on groundwater recharge from complex landscape mosaics and influences nutrient delivery to downstream rivers and estuaries. Irrigation using surface water depends on a complex system of allocating water that considers native flows, stored water, priority water rights, and return flows, often extending throughout an entire river basin.

BOUNDARY ORGANIZATIONS

Some organizations are likely to be more effective than others in engaging in landscape conservation efforts. Those that may be more effective are ones that are able to bridge the knowledge-action boundary (Cash et al., 2003; Cook et al., 2013); that is, they understand the need for scientific information and data to inform conservation interventions, but they are also able to use such information in implementing conservation strategies and actions. In some cases, these organizations generate scientific information either directly or indirectly, but they also consume that information in advancing conservation actions that depend on the underlying science. Organizations that are able to bridge this knowledge-action boundary are referred to as boundary organizations and often employ or are able to facilitate dialogue across groups of scientists as well as natural resource managers and conservation practitioners who actually implement conservation. Nongovernmental organizations are often examples of boundary organizations because of their abilities to facilitate scientists, decision makers, and other stakeholder groups across landscapes (Cook et al., 2013). For example, the Ecosystem-Based Management Tools Network3 “provides a wide range of training and outreach activities to connect practitioners with tools that incorporate

___________________

3 See http://www.ebmtools.org.

natural and social science into decision making.” The design and structure of LCCs suggest that they are intended to function as boundary organizations at large landscape scales by fostering collaboration among managers and stakeholders across multiple jurisdictions. It appears that in many cases, they may be able to fill this role, and may become more effective in fulfilling their missions if they are able to do so.

CHALLENGES OF LAUNCHING A LANDSCAPE APPROACH

Given the complex jurisdictional arrangements described above, it might not be surprising that the launch of the LCCs under the direction of the FWS encountered some challenges. First, this new program has been met with some criticism or skepticism. In its information-gathering process, during both committee meetings and informal phone conversations, the committee learned that the program was initially perceived by some stakeholders as a new federal mandate (as it was a Secretarial Order), as federal overreach, as a new program potentially decreasing funds for other, well-established FWS programs, and as yet another collaboration when there were already so many meetings to attend.

Because it was launched by a single agency in response to a Secretarial Order, its initial launch ran counter to the intent of the program and counter to the current social science research that stresses the importance of early involvement of relevant stakeholders to develop stakeholder engagement, trust, and buy-in (Cash et al., 2003). Thus, during the implementation, much of these initial perceptions needed to be overcome first before trust could be built. Furthermore, it appears that during the development of partnerships with individual LCCs, many of the same partners that the FWS typically engages were at the table. This could, in part, explain why the initial efforts by the LCCs appear to be primarily focused on natural resources, and why the methods by which the LCCs plan to address cultural resources are still not clear. As the LCCs evolve, benefits could be derived from engaging other state partners such as state parks, water agencies, and/or forestry agencies. This would serve to alleviate some of the burden of coordination among state agencies. The committee learned during its information-gathering process that during the process of engaging stakeholders and identifying their needs and priorities, a number of skeptical stakeholders began to recognize the potential benefits of this program.

CONCLUSIONS

Most of the major threats to conservation of natural and cultural resources in the United States today, including climate change impacts, occur at large spatial scales across vast regions, often as a result of historical or current land-use practices. To respond to these challenges, it is necessary to understand the underlying science of large landscapes and seascapes, and for different stakeholders and constituencies to work together across federal, state, local, and private jurisdictions. No single government agency, corporation, or nongovernmental organization is capable of doing this alone. The sage-grouse case study in Appendix A, based on a broad partnership initiated at the state level, illustrates the benefits from a landscape approach that helped avert the need for listing the species under ESA.

LCCs were created to convene different stakeholders to work together across geopolitical boundaries to take on these large-scale conservation challenges, including providing and further developing the underlying science capacity needed to address these problems. The committee concludes that the LCCs are appropriately based on modern conservation science and that, in concept, their design and implementation (with the exception of their initial launch) to date reflect an appropriate scientific response to conservation challenges at large scales.

The committee also concludes that the LCC boundaries appear to be largely fixed, in contrast to the definition of a landscape approach, which depends on the resources being managed. However, there is great emphasis in the LCC Network Strategic Plan to identify and address priorities that span multiple LCCs. One way the LCC Network has dealt with this matter is through initiating joint activities involving from two to seven LCCs (see Appendix B and further discussion in Chapter 6). In addition, the LCC Network has a process that allows for LCC boundaries to change under some circumstances (LCC Network, 2011; see footnote, p. 19). The committee applauds this flexibility, and encourages the LCC Network to explore the degree to which short- or long-term boundary changes can be helpful in achieving the program’s mission.

This page intentionally left blank.