5

The Landscape Conservation Cooperatives and Other Similar Federal Programs

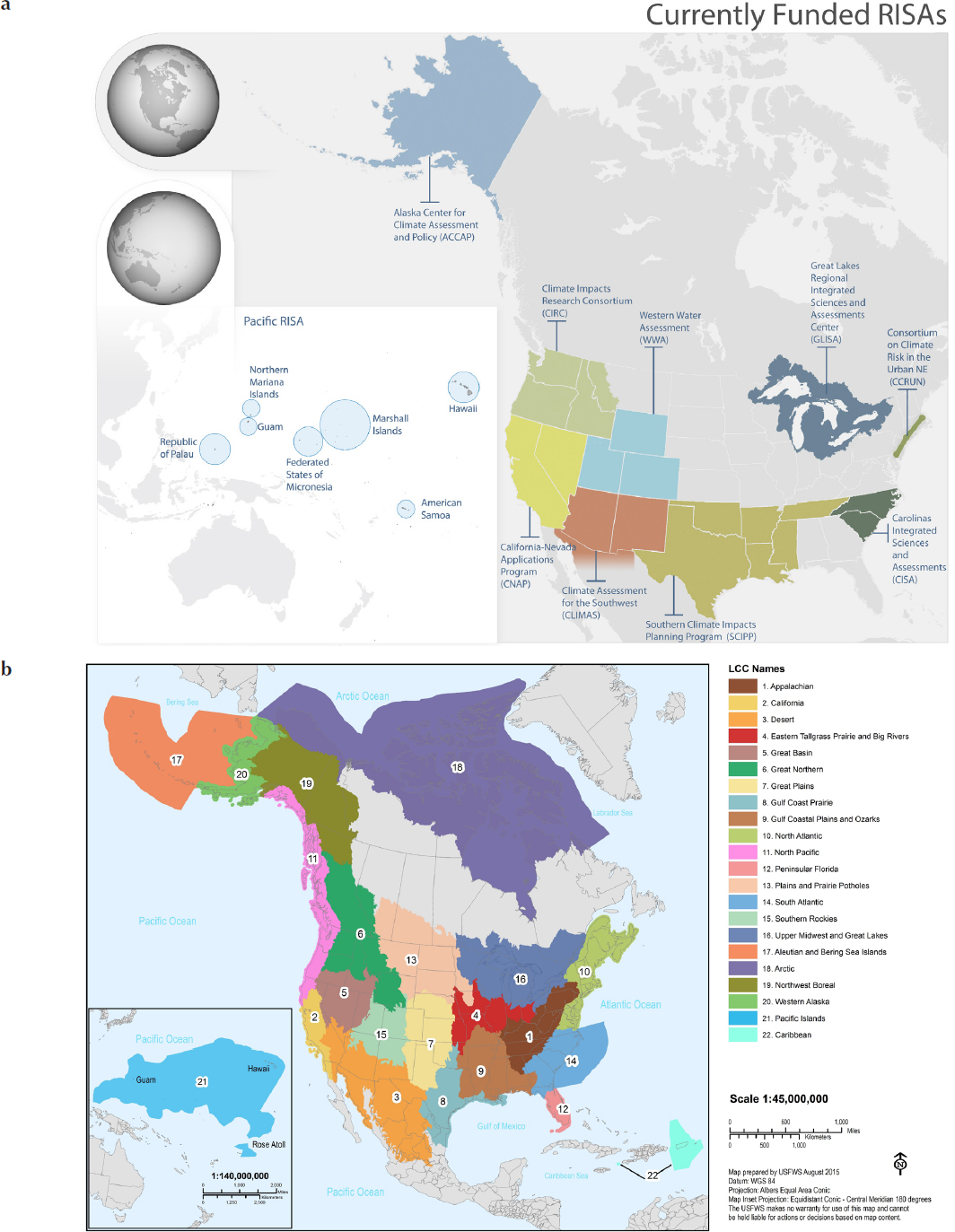

In this chapter, the committee addresses Tasks 2 and 3 of the statement of task (see Chapter 1), which, in brief, ask the committee to (a) compare the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives (LCC) program with other similar programs, considering similarities, differences, overlap, and coordination; and (b) compare activities supported by LCCs and related programs within the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and other agencies, and whether there is sufficient coordination and integration. To address these tasks, the committee reviewed and discussed similar programs that are federally funded1 (see Table 5.1 for a brief overview). There is a large number of existing federal programs that focus on conservation, and this review should not be considered comprehensive. Rather, this chapter and Appendix D include programs reviewed by the committee and, in particular, programs that were commonly referred to as potentially overlapping with the LCCs during the committee’s information-gathering efforts.

The committee considered initially more than 20 programs, including federal research laboratories and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Cooperative Research Units. After cursory review, the committee narrowed its analysis to 11 other programs that operate sub-nationally but across a considerable span of the United States and affiliated territories (in some cases, as with LCCs, these groups also have regionally organized governance structures), and that have a focus on landscape conservation and/or adaptation to climate change. The committee gave no further consideration to programs, including those within the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), whose primary purpose is the generation of scientific research, but that otherwise lack multiple key characteristics in common with LCCs, such as a landscape-scale focus, stakeholder involvement, or a large geographic domain.

Considering the five attributes below (see Box 5.1), the committee examined the 11 programs listed in Table 5.1 for overlap with the LCCs, and identified four programs sufficiently similar to LCCs in scope, scale, organization, and emphasis to warrant a closer examination: FWS’s Migratory Bird Joint Ventures program (Joint Ventures), FWS’s Fish Habitat Partnerships (FHPs), USGS’s Climate Science Centers (CSCs), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments (RISA) program. A brief discussion of the other seven programs is provided in Appendix D. The committee also discusses the regional-scale coordination among programs in the Pacific Islands and the Southeast United States. Finally, the committee concludes the chapter with feedback on how the LCCs can be best positioned to support and coordinate with similar conservation efforts or related activities.

DETAILED CONSIDERATION OF SIMILAR PROGRAMS

To gauge the programs’ similarity to LCCs, the committee considered the five attributes listed in Box 5.1. After examining numerous documents describing the various programs and considering these five attributes, the committee judged the degree of similarity to the LCCs to be roughly in the order presented in Table 5.2 and chose to concentrate its in-depth analysis on FWS’s Joint Ventures, FWS’s FHPs, USGS’s CSCs, and NOAA’s RISA Program.

Migratory Bird Joint Ventures

Responding to reductions in waterfowl populations and habitat, the U.S. and Canadian governments developed the North American Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP, 2012) to restore waterfowl populations. The NAWMP was first adopted in 1986 and has been updated several times since then. Congress passed the North American Wetlands

___________________

1 Because of the vast number of collaborative conservation efforts throughout the nation, the committee elected to interpret “similar programs” and “related programs” as those within the purview of federal agencies.

TABLE 5.1 Overview of the LCCs and 11 Other Federal Programs Considereda

| Entity and Primary Focus | Geography, Structure, and Governance | Mission (Paraphrased) |

|---|---|---|

| Landscape Conservation Cooperatives (LCCs)* Conservation strategies through technical support |

22 LCCs cover the U.S. land area, territories, Pacific and Caribbean islands, and parts of Canada and Mexico, and broadly participate in many activities. They are advised by a steering committee with members from a range of public and private conservation and resource management partners. | LCCs develop and provide integrated science-based information about the implications of climate change and other stressors for the sustainability of natural and cultural resources and develop landscape-level conservation objectives. |

| Migratory Bird Joint Ventures (JVs)* Large habitat or species conservation |

22 habitat-based JVs and three species-based JVs cover all of the United States, Canada, and a large part of Mexico. They are advised by an independent management board with members from a range of public and private conservation and resource management partners. | JVs benefit migratory bird populations, other wildlife, and the public by sustaining a diversity of habitats through cutting-edge science and technology. |

| U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) Fish Habitat Partnerships (FHPs)* Large habitat or species conservation |

19 FHPs (18 based on particular geographies or species, and 1 based on a particular type of system) cover the U.S. land area, territories, and parts of Canada. | FHPs protect, restore, and enhance fish and aquatic communities and habitats. The partnerships foster fish habitat conservation and improve the quality of life for the American people. |

| U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Climate Science Centers (CSCs) and the National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Center (NCCWSC)* Research to support management of fish, wildlife, and habitat |

Eight centers cover the U.S. land area and territories. Each is a USGS–university cooperative agreement and has an advisory council composed exclusively of federal, state, and tribal representatives. NCCWSC provides overall coordination for the eight CSCs. | CSCs provide science support to natural resource managers for dealing with effects of climate and other concurrent global changes on fish and wildlife and their habitats. |

| National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments (RISAs) Build resilience to climate through stakeholder-driven research |

11 RISAs,b all housed at universities (domain determined by proposers), collectively cover roughly 75% of U.S. land area. Priorities, topics, and governance vary widely. | RISAs act as a research engine for partnership-driven science to expand the nation’s capacity to prepare for and adapt to climate variability and change. |

| National Park Service (NPS) Scaling-Up initiative* Conservation of areas adjacent to national parks |

The initiative focuses on the 408 units of the national park system (covering 84 million acres) operated by the NPS, including 30 national historic and scenic trails and 49 National Heritage Areas. | The initiative preserves natural and cultural resources within national parks, trails, heritage areas, and landmarks by improving conditions beyond those boundaries through a larger-landscape approach to conservation. |

| Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Landscape-Scale Approach to Managing Public Lands* Resource conservation, restoration, and development |

BLM administers more than 245 million acres located in the 12 western states. BLM Ecoregions cross traditional administrative boundaries. | The ecoregional approach identifies important habitats for fish, wildlife, and species of concern, and their vulnerability to climate change, wildfires, invasive species, and development. |

| NOAA Regional Collaboration Teams Conservation and restoration of coastal and marine habitat |

Eight Regional Collaboration Teams within NOAA integrate NOAA employees and affiliates to promote regional coordination of NOAA assets in order to better address stakeholder concerns. | The Regional Collaboration Teams serve as flexible networks of NOAA staff and affiliates who engage with stakeholders, assess the needs of external partners and stakeholders, and adjust NOAA products and services accordingly. |

| U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Regional Climate Hubs Provision of climate information to private landowners |

Seven Regional Climate Hubs cover the U.S. land area and some territories. The program currently consists primarily of part-time directors with small budgets. | Regional Climate Hubs provide information to farmers, ranchers, and forest landowners to help them adapt to the impacts of climate change and promote sustainability. |

| Entity and Primary Focus | Geography, Structure, and Governance | Mission (Paraphrased) |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Forest Service (USFS) Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP) All lands, collaborative, science-based ecosystem restoration of priority forest landscapes |

USFS manages more than 192 million acres of forestlands and grasslands. The CFLRP is an approach to conserving priority forests led by USFS in close coordination with other landowners to encourage collaborative solutions through landscape-scale operations. The program uses a competitive process to allocate funding to collaborative groups to implement management activities. | The CFLRP encourages ecological, economic, and social sustainability, reduces wildfire management costs, and demonstrates effectiveness of ecological restoration techniques. |

| Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Landscape Conservation Initiatives Helps the agricultural sector contribute to conservation goals best addressed on a landscape scale |

Nationwide program with designated priority areas—Critical Conservation Areas. Also includes Chesapeake Bay Watershed and the Mississippi River Basin. It provides assistance to landowners through grants from the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP). | RCPP promotes coordination for landscape-scale initiatives among NRCS and its partners to assist producers and landowners in conservation. |

| U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration Environmental and military considerations near DoD facilities |

Projects are located around military lands and include designated Sentinel Landscapes, a nationwide federal, local, and private collaboration dedicated to promoting natural resource sustainability and working lands in areas surrounding military installations. | DoD Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration program coordinates mutually beneficial programs and strategies to preserve, enhance, or protect habitat and working lands near military installations, and reduce, prevent, or eliminate restrictions that inhibit military testing and training. |

a U.S. Department of Interior programs are indicated by asterisks.

b Since this report entered review, the committee has learned that the Southeast Climate Consortium is no longer currently funded, though they will have an opportunity to apply for future funds again. Therefore the RISA program now currently supports 10 regional research teams, not 11. Because the committee learned of this after the report entered review, references to the Southeast Climate Consortium remain throughout this chapter.

TABLE 5.2 Description of the Five Programs Relative to the Five Attributes

| Attribute | Program | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Conservation Cooperatives (LCCs) | FWS Migratory Bird Joint Ventures (JVs) | USGS Climate Science Centers (CSCs) | NOAA Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments (RISAs) | FWS Fish Habitat Partnerships (FHPs) | |

| Extent of land area covered | Cover all U.S. states and territories, and parts of Canada and Mexico | Covers essentially all of the United States, Canada, and a large part of Mexico | Cover all U.S. states and territories | Cover ~75% of U.S. land area | Nominally all of the United States but in reality, mostly riparian areas and adjacent lands |

| Emphasis on conducting scientific research | Fund extramural research and other activities | Some conduct original research, others fund extramural research and other activities | Fund extramural research and other activities; more research than LCCs | Conduct original research | No research |

| Emphasis on climate as a driving issue | Varies across the network as determined by each LCC’s stakeholder group | Low priority | Prominent | Prominent | Low priority |

| Emphasis on conservation within stated priorities and demonstrable activities | Conservation is a top priority | Conservation is a top priority | Conduct research, in part to support conservation, but do not do conservation projects | Little to no emphasis on conservation | Conservation is a top priority |

| Degree to which the program’s governance is concentrated in a single agency | LCCs are each steered by a broadly drawn stakeholder group | JVs are each steered by a broadly drawn stakeholder group | USGS–university cooperative agreement; USGS side has broadly drawn stakeholder advisory council for each CSC | Housed at universities | FHPs are each steered by a broadly drawn stakeholder group |

NOTE: FWS = U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; NOAA = National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; USGS = U.S. Geological Survey.

Conservation Act2 in 1988 in support of the NAWMP and to provide grants to carry out wetlands conservation projects. Mexico officially joined the NAWMP in 1994. Although the plan is international in scope, planning and implementation occur at regional levels.3 These regional efforts, known as Joint Ventures, seek to bring together the relevant agencies, organizations, and stakeholders to conserve habitat for migratory birds, other wildlife, and people within their region.4

The Joint Ventures enable partners to engage, both together and independently, in activities that support specific bird and bird habitat conservation goals within their geographic region. The activities conducted by the Joint Ventures and their partners range from biological planning, conservation design, habitat conservation (i.e., implementation), communication and outreach, monitoring, evaluation, and applied research.5

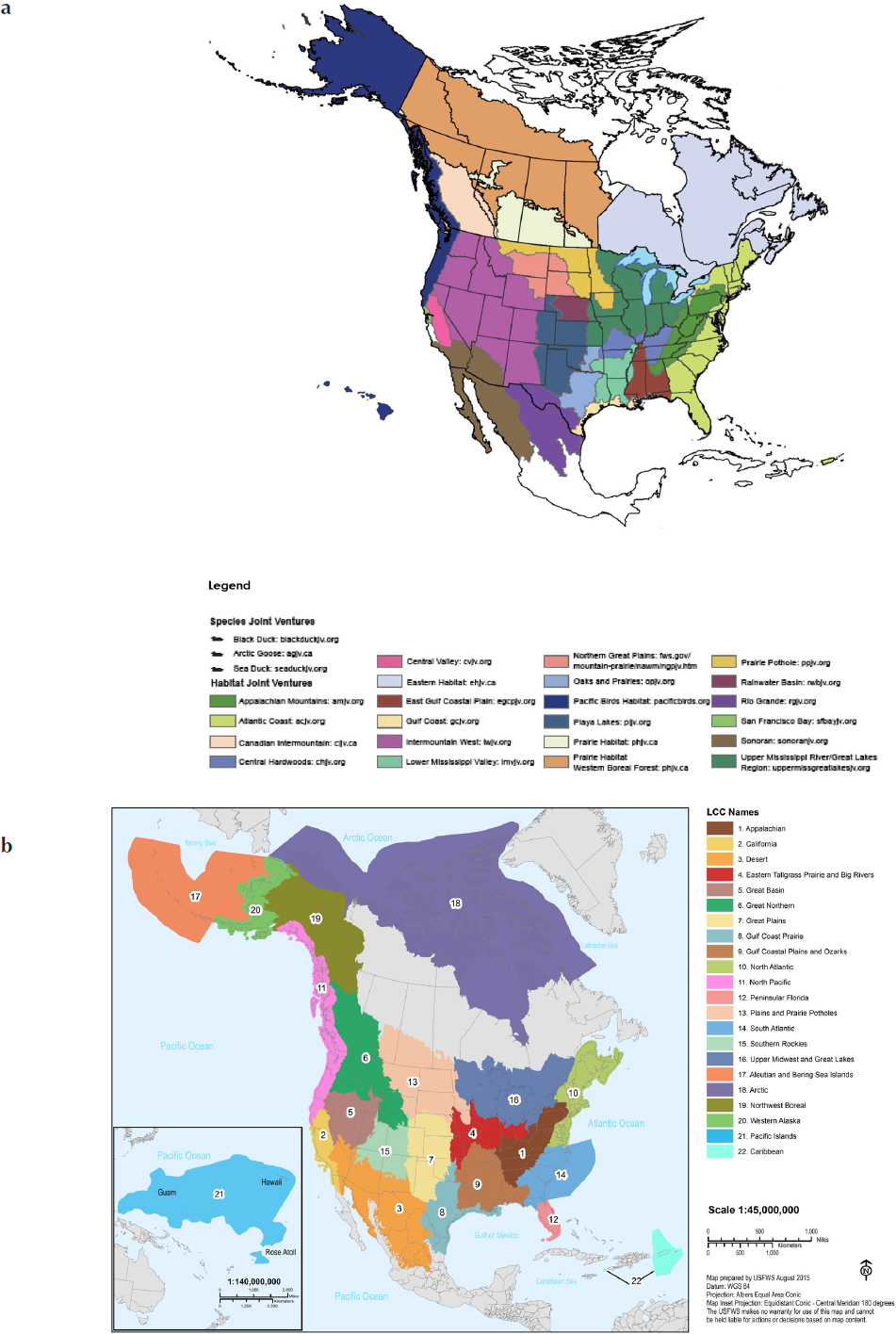

The first Joint Venture was formed in 1986, and today there are 22 habitat-based Joint Ventures (see Figure 5.1); 18 in the United States and 4 in Canada.6 Each Joint Venture is governed by a management board that directs its activities and oversees its implementation planning; membership of the boards is determined within each Joint Venture and includes representatives from the organizations participating in the Joint Venture partnership. Joint Ventures also have one or more technical committees that provide scientific advice related to conservation goals. Each Joint Venture is staffed by a coordinator, and many also include additional positions in science coordination, science delivery, or communication.7

An Association of Joint Venture Management Boards has been organized that includes management board chairs and members from each of the Joint Ventures.8 This association develops common messages about the impacts and successes of Joint Ventures and provides a forum to share les-

___________________

2 16 U.S.C. §§ 4401-4414.

3 See http://www.fws.gov/birdhabitat/NAWMP/index.shtm.

4 See http://mbjv.org/who-we-are.

5 See http://www.fws.gov/policy/721fw6.html.

6 See http://mbjv.org/who-we-are.

7 See http://mbjv.org/who-we-are; http://www.fws.gov/policy/721fw6.html.

SOURCES: http://www.fws.gov/birdhabitat/JointVentures/files/JointVentureFactSheet.pdf; https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/55b943ade4b09a3b01b65d78.

sons learned across individual Joint Ventures, but it does not direct their efforts.9 Joint Ventures receive support through U.S. congressional appropriations to the FWS,10 as well as additional federal, state, and private funding provided by partner organizations. The FWS typically provides funding for the coordinator and basic program infrastructure.11

Similarities with LCCs: In the 2012 revisions to the NAWMP, the Joint Venture approach of advancing conservation objectives through regional partnerships was cited as serving as a model for the LCCs and other emerging conservation efforts (NAWMP, 2012). Indeed, through communication with FWS personnel and a range of stakeholders, the committee learned that the Joint Ventures served as an inspiration for the LCC program. As a result, the LCCs naturally resemble the Joint Ventures in many ways. The Joint Ventures, like the LCCs, are self-directed partnerships organized at a regional level that together cover the entire United States and extend into Canada and Mexico. The governance structure for each program is similar: decisions for individual Joint Ventures and LCCs are made by representatives from the organizations participating in each partnership (management boards for the Joint Ventures and steering committees for the LCCs). Some Joint Ventures engage both a steering committee and a management board, the latter playing the role of implementing joint priorities (see Chapter 6 for a discussion of the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture). This structure is designed to ensure that the focus and specific project objectives for each Joint Venture and LCC address regional needs rather than being driven by national-level priorities. While each program includes some national-level organization (the Association of Joint Venture Management Boards and LCC Council), they are specifically designed to support efforts of the regional partnerships by enabling sharing of lessons learned, increasing awareness of the Joint Venture or LCC programs and related successes, and encouraging support of and participation in regional efforts. Many individual Joint Ventures and LCCs also have a science or technical committee to provide guidance on the best available science to inform partnership decisions.

The LCCs are described in LCC Information Bulletin No. 1 (Office of the Science Advisor, 2010) as “applied conservation science partnerships” designed to support conservation at the landscape scale. Similar to the Joint Ventures, they are intended to facilitate collaboration among the DOI bureaus and with other resource management agencies and organizations at the federal, state, and local levels, creating partnerships that are capable of “accomplish[ing] conservation objectives that no single LCC, nor any agency or organization, could accomplish alone.” Also similar to the LCCs, the Joint Ventures operate across national borders to coordinate conservation with Canada and Mexico.

Differences from LCCs: Although the LCCs have much in common with the Joint Ventures, the primary difference between these programs is in their programmatic scope. The Joint Ventures have a relatively narrow focus on migratory bird and bird habitat conservation.12 In contrast, the LCCs have a broader focus on natural and cultural resources more generally.13 While individual LCCs may engage in some projects that support conservation of birds or bird habitats, their purview is much broader and may focus on other conservation issues deemed to be a priority in a particular area; indeed a review of LCC projects demonstrates a broad range of supported topics.14 Joint Ventures have also been actively implementing conservation and monitoring activities, distinguishing them from the LCCs, which have so far focused more on collaboration, information sharing, and science development (see additional discussion in Chapter 6). Although LCCs intend to catalyze conservation, they are not yet viewed as a program that implements conservation the same way the Joint Ventures are perceived.

Coordination with LCCs: The committee found several existing avenues for limited coordination between the LCCs and Joint Ventures. An examination of the rosters of LCC advisory committees reveals many names with Joint Venture affiliations, either staff or management board members. In addition, some LCCs have funded joint projects with Joint Ventures: the list of LCC-funded projects includes 23 projects that mention Joint Ventures as partners or joint funders. Most of those (12) are with the California LCC.

Fish Habitat Partnerships

In 2006, a coalition of state, tribal, territorial, and federal government representatives as well as anglers, conservation groups, and scientists developed a National Fish Habitat Action Plan. The purpose of the plan was to encourage “voluntary, non-regulatory, science-based action to protect, restore, and enhance America’s aquatic systems.”15 The effort was spearheaded by states through the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (AFWA) in cooperation with the FWS and NOAA, which served as the primary liaisons to other federal agencies and other partners.16

___________________

9 See http://mbjv.org/who-we-are/networks.

10 Congressionally appropriated funds for both the LCCs and Joint Ventures are provided through an appropriation for “Resource Management.” In a congressional report that accompanies the appropriating legislation, Congress clarifies how those funds are to be divided among various programs, including the LCCs and Joint Ventures (e.g., H.R. 2822, 114th Cong. 2015 and H.R. Rep. No. 114-170, p. 13).

11 See http://www.fws.gov/policy/721fw6.html.

12 See http://www.fws.gov/birdhabitat/JointVentures/index.shtm.

13 See http://lccnetwork.org/about.

14 See http://lccnetwork.org/projects.

15 See http://fishhabitat.org/sites/default/files/www/NFHP_AP_Final_0.pdf.

16 See http://fishhabitat.org/sites/default/files/www/National%20Fish%20Habitat%20Action%20Plan%20-%20National_Fish_Habitat_Action_Plan.pdf.

The plan called for the organization of a network of regional FHPs focused on important aquatic habitats and species. These partnerships serve as the working units of the National Fish Habitat Action Plan and are overseen by the National Fish Habitat Board. The National Fish Habitat Board comprises 22 members representing a variety of stakeholder groups, including state and federal agencies, tribal governments, conservation groups, resource managers, and academia. Members of the board are approved by an executive leadership team that includes the president and executive director of AFWA, the assistant administrator for Fisheries at NOAA, and the director of the FWS. The purpose of the National Fish Habitat Board is to provide leadership and coordination, approve and support FHPs, establish interim and long-term national conservation goals, support regional goals, mobilize support, and measure and communicate the status and needs of fish habitat. Staff support for the National Fish Habitat Board is provided by AFWA, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, the FWS, NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, and USGS.17

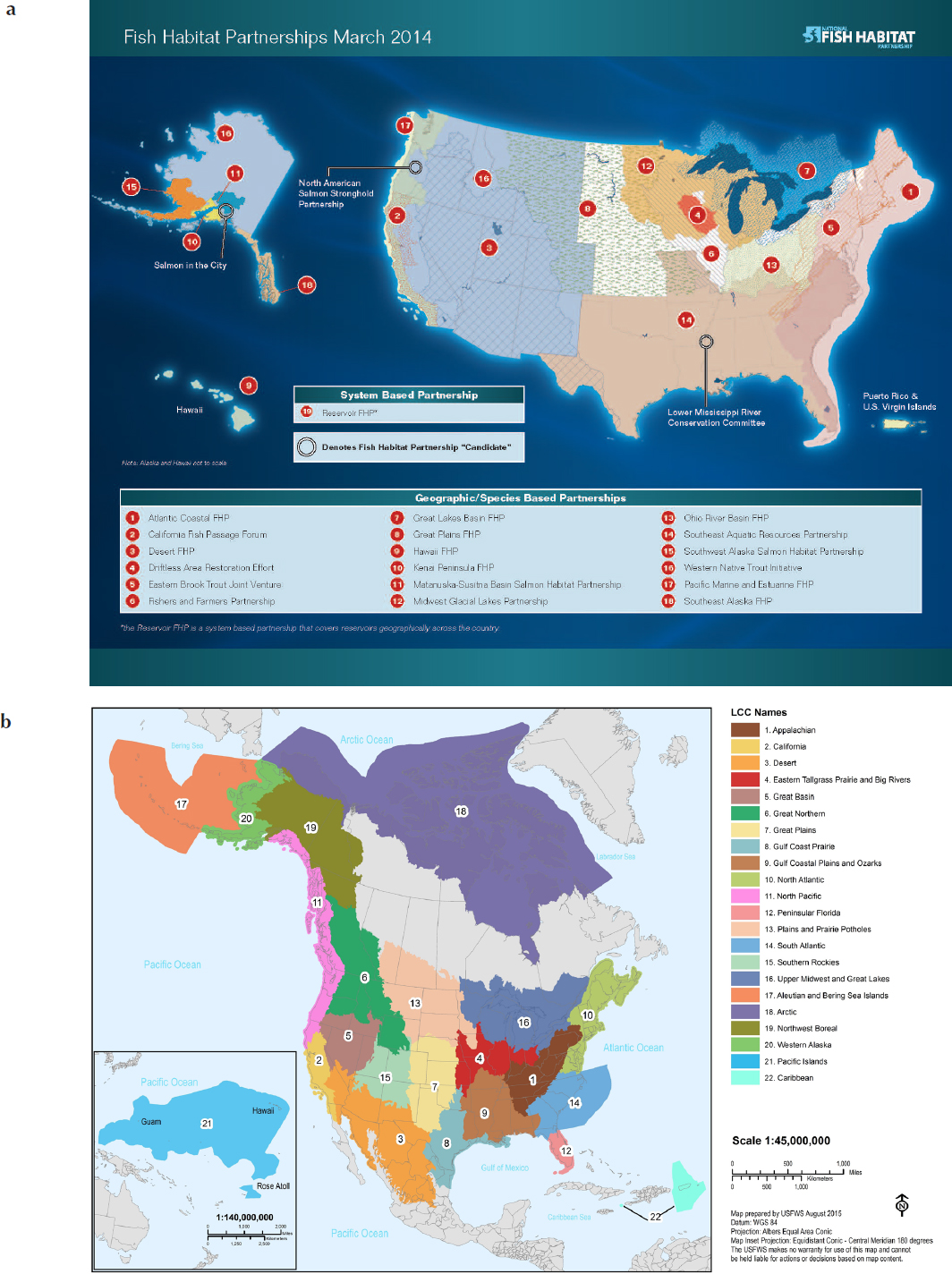

By 2012, when an updated second edition of the National Fish Habitat Action Plan was released, the National Fish Habitat Board had approved 18 regional FHPs, and in 2014, a 19th regional FHP in Southeast Alaska was approved. Among the 19 FHPs, all 50 states are represented in at least one partnership.18 Of the 19 FHPs, 18 are based either on a particular geographic region or a particular species of fish. The Reservoir Fish Habitat Partnership is considered to be a “system-based” partnership that includes reservoirs throughout the country (see Figure 5.2).

Similarities with LCCs: Like the LCCs, the National Fish Habitat Partnership was modeled after the Joint Ventures program,19 and therefore, shares many traits with both the Joint Ventures and the LCCs in terms of structure and function. Like the LCCs and the Joint Ventures, the individual Fish Habitat Partnerships are considered self-directed. The updated National Fish Habitat Action Plan (2012) describes them as “self-identified, self-organized, and self-directed communities of interest formed around geographic areas, keystone species, or system types.” They also resemble the Joint Ventures and LCCs in that they are overseen by a board at the national level, but they are primarily intended to operate at a regional scale through individual, cross-jurisdictional partnerships of diverse stakeholders. The individual FHPs are also typically led by a steering committee.

Differences from LCCs: As with the Joint Ventures, the primary difference between the FHPs and LCCs is their scope. Because these partnerships focus on a particular taxonomic group, their focus is also not as broad as the LCCs, which focus on natural and cultural resources generally. Whereas several LCCs include partners in Canada or Mexico, with one exception (the Great Lakes Basin Fish Habitat Partnership) the FHPs focus solely on U.S. waters. Another difference from the LCCs is that there is substantial geographic overlap among the FHPs. In contrast to the LCCs and according to the National Fish Habitat Action Plan (2012), the primary focus of the FHPs is to implement conservation projects.

Coordination with LCCs: Despite the differences in geography and focus just noted, the confluence of conservation priorities sometimes brings LCCs and FHPs to work together. The committee found multiple references to collaborations between LCCs and FHPs, including but not limited to coordination on fish habitat assessments. For example, the Plains and Prairie Potholes LCC worked with FHPs to develop advanced fish habitat assessment models to support efficient, targeted, and strategic management of aquatic resources.20 The committee also noted some overlap in the membership of the Fish Habitat Partnership steering committees and the membership of steering committees of the LCCs.

Climate Science Centers and National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Center

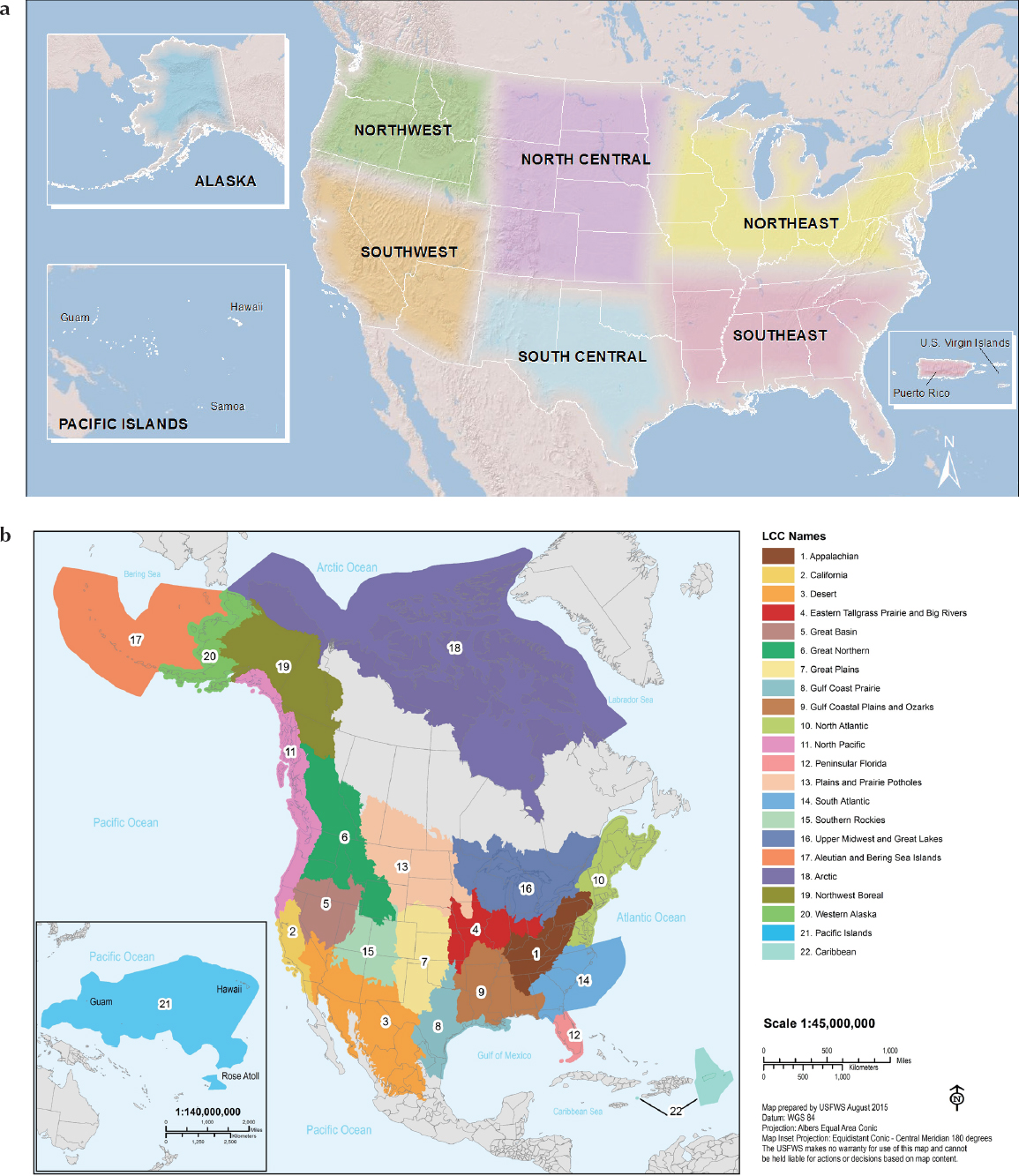

USGS’s National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Center (NCCWSC) serves as the managing entity for eight regional CSCs. The CSCs were established by the same Secretarial Order (No. 3289; see Appendix E) that established the LCCs, and were intended to provide information about climate change to all DOI bureaus. The LCCs and CSCs were intended to be complementary, with the CSCs focused more on research and LCCs on delivering information and convening partners for developing shared conservation strategies. Like the LCCs, the eight CSCs together span the entire contiguous United States from coast to coast, as well as Alaska, Hawaii, and the U.S. territories (see Figure 5.3). The eight CSCs are all housed at research universities that were selected through a competitive process.

Each CSC has the responsibility and opportunity to establish its own goals and research priorities in consultation with its Executive Stakeholder Advisory Committee, which entirely comprises federal, state, and tribal representatives. LCC coordinators are key stakeholders on the Executive Stakeholder Advisory Committees and as such serve an important function in ensuring that each CSC is responsive to LCC needs. NCCWSC has developed its own strategic plan, which includes some goals and aspirations for the CSCs. It also has its own advisory committee, but unlike the regional

___________________

17 See http://fishhabitat.org/sites/default/files/www/NFHP_AP_Final.pdf.

18 See http://fishhabitat.org/sites/default/files/www/NFHP_AP_Final.pdf.

19 See http://www.fws.gov/fisheries/whatwedo/NFHAP/nfhap_who.html.

SOURCES: http://fishhabitat.org/sites/default/files/FHP_Map_Main_14_1.pdf; https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/55b943ade4b09a3b01b65d78.

SOURCES: https://edit.doi.gov/csc/centers; https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/55b943ade4b09a3b01b65d78.

Executive Stakeholder Advisory Committees, none of the members are leaders of LCCs or its national program.21

Similarities with LCCs: Both the LCCs and the CSCs were created by the same Secretarial Order and cover the geography of the United States and its territories; both are housed in DOI; both award external grants; and both are guided by steering committees that have some ability to make recommendations including funding decisions, with the final decisions resting on the regional director (for the FWS). Furthermore, members of the respective steering committees comprise similar stakeholder groups; thus, potentially resulting in the identification of similar priorities. Both have an emphasis on climate science to support decisions, including cultural and natural resource management.

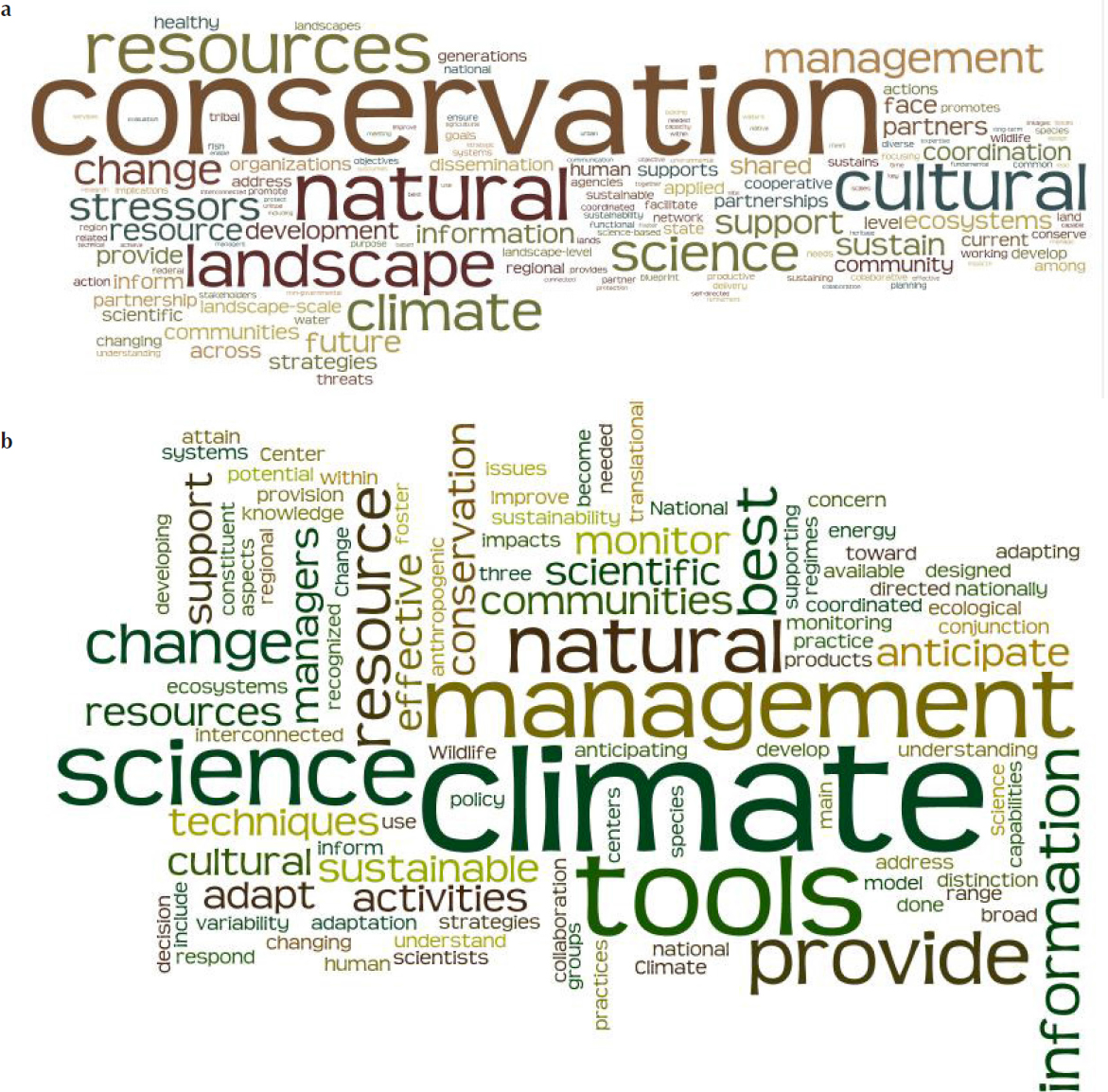

Differences from LCCs: As described in the Secretarial Order, the 22 LCCs and 8 CSCs were intended to be distinct but complementary. LCCs were intended to focus more on convening conservation partners to develop common conservation priorities and Landscape Conservation Designs as well as the applied science and tools to inform these conservation priorities. In contrast, CSCs were intended to focus on carrying out the research needed to support conservation and resource management in the face of climate change. CSCs are not designed to develop conservation strategies and Landscape Conservation Designs, but focus primarily on research. Structurally, CSCs consist of a university component competitively awarded on a 5-year cooperative agreement, and of a small number of USGS staff who direct USGS funding to a portfolio of research projects. By contrast, LCCs have no university component. The Executive Stakeholder Advisory Committees for CSCs consists solely of state, federal, and tribal representatives; the steering committee of LCCs includes much broader participation (e.g., nongovernmental organizations [NGOs] and private sector). Whereas all CSCs have a significant focus on climate, there is wide variety among LCCs in the prominence of climate issues in their communication, activities, and funded projects. A comparison of word clouds created from the mission statements of the individual LCCs and CSCs (after removing geographically specific terms and every occurrence of the name of the entity) reveals a much greater emphasis on climate, tools, and science in the CSCs, and much greater emphasis on conservation in the LCCs, reflecting the needs of their stakeholders (see Figure 5.4).

Coordination with LCCs: Relevant LCC coordinators are usually on the steering committee for CSCs, though not usually the reverse (since some CSC regions touch as many as seven LCCs). In some instances, CSCs and LCCs have jointly funded projects. The list of LCC-funded projects includes seven that were jointly funded with CSCs, mostly in Alaska. An additional two LCCs listed CSCs as leverage, and a number of LCC projects list CSCs as participants. At least 10 persons listed on the rosters of LCC advisory councils are directors or other leaders of CSCs. The LCCs and CSCs have also coordinated on meetings, workshops, and symposia. For example, the Southwest Climate Summit was organized jointly by the Southwest CSC, California Nevada Climate Applications Program, and the California LCC. The Pacific Island LCC and Pacific Island CSC have also cohosted two Climate Science Symposia.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments Program

The RISA program dates back to 1995 and was developed within NOAA to “pioneer innovative mechanisms for enhancing the value of climate information and products for understanding and responding to these challenges at the regional scale” (Binder et al., 2009). The RISA program now supports 11 regional research teams22 that help expand and build the nation’s capacity to prepare for and adapt to climate variability and change. RISA teams work with public and private user communities to develop knowledge on impacts, vulnerabilities, and response options through interdisciplinary research and participatory processes. Climate information can inform decisions intended to promote adaptation to a changing environment, but only if the climate research community and decision makers work together to understand each other’s needs and limitations. Successful outcomes from the RISA program are due in part to their ability to create lasting relationships with decision makers from the public and private sectors including local, regional, and state governments, federal agencies, tribal governments, utilities, the business community, and national and international nonprofit organizations (Pulwarty et al., 2009; Meadow et al., 2015). Through these relationships, RISA teams learn about specific decision contexts within and across different sectors of society, advancing the overall understanding of the use of science.23

Similarities with LCCs: Like LCCs, RISAs aim to serve a variety of functions: supporting and conducting research, developing tools or other approaches to support decision makers, and convening stakeholders, to name a few. Each RISA has the latitude to set its own priorities, choose which stakeholders to engage, and to some extent create its own approach to governance. Similarly, LCCs also have the

___________________

21 See https://nccwsc.usgs.gov/content/acccnrs-member-list.

22 Since this report entered review, the committee has learned that the Southeast Climate Consortium is no longer currently funded, though they will have an opportunity to apply for future funds again. Therefore the RISA program now currently supports 10 regional research teams, not 11. Because the committee learned of this after the report entered review, references to the Southeast Climate Consortium remain throughout this chapter.

23 See http://cpo.noaa.gov/ClimatePrograms/ClimateandSocietalInteractions/RISAProgram/AboutRISA.aspx.

authority as self-directed partnerships to develop their own diverse priorities and, to a lesser extent, however, to determine their own leadership.

Differences from LCCs: The RISA program is quite different from LCCs in mission, governance, topical focus, and goals. RISAs, whose core participants are based at universities, are much more focused on research, and are created through a competitive process by proposing teams of university scientists, not by an agency. RISAs, unlike CSCs and LCCs, do not cover the entire country, as can be seen in Figure 5.5. The teams of university scientists propose regional boundaries, select the key participants, determine the composition and structure of their advisory councils (if any), and determine

the priorities. RISAs do not themselves provide external funding for projects the way LCCs do; instead, they carry out their research agenda and other activities with the proposing team and often with leveraging (as with LCCs). Broadly, RISAs focus more directly on human considerations like urban water availability, public health, and community resilience; and RISA teams generally include social scientists.

Coordination with LCCs:

RISAs and LCCs primarily coordinate by convening joint meetings, workshops, conferences, and training events. For example:

- The Great Basin LCC and California-Nevada Assessment Program have organized a series of six Great Basin Climate Forums and two Tribal Climate Adaptation Workshops; combining forces has led to more effective dissemination and application of climate information, participants assert.

- The Desert LCC, and the Southwest and South Central RISAs co-convened a U.S.-Mexico binational climate change adaptation workshop, concentrating on the Big-Bend stretch of the Rio Grande Basin.24

- LCC coordinators serve on steering committees of at least two RISAs: the Alaska RISA25 and the Northwest Climate Impacts Research Consortium,26 and conversely, RISA participants serve on science advisory committees for at least two LCCs (the Northwest Climate Impacts Research Consortium on the North Pacific LCC, and Western Water Assessment on the Southern Rockies LCC27).

COORDINATION AMONG REGIONAL PROGRAMS

In this section, we examine in more detail the coordination among LCCs, CSCs, and RISAs in two geographic regions. We selected the Pacific Islands because the geographic boundaries of the Pacific Islands LCC, the Pacific Islands CSC, and the Pacific RISA are nearly identical, affording an organizationally simple framework to examine the interactions among the three types of regional programs. Because the alignment of geographic boundaries for these programs is not typical, we also analyzed in more depth the coordination among the Southeast CSC and its six affiliated LCCs and three RISAs.

Pacific Islands

The geographic extent includes the state of Hawaii and U.S.-affiliated Pacific territories, including Guam, American Samoa, and the Federated States of Micronesia. The committee learned from conversations with stakeholders involved in these programs that people in this vast, far-flung, and sparsely populated region rely on and value remote connections, personal networks, and collaborations. Therefore, organizations offering such networking, as well as decision-relevant research and products, like the Pacific Islands LCC, Pacific RISA, and Pacific Islands CSC, are valued.

Several examples serve to illustrate the collaboration and synergies of these three organizations. The Pacific Islands LCC and Pacific Islands CSC have cohosted two Climate Science Symposia.28 The Pacific Islands LCC and Pacific RISA collaborated on the Pacific Islands Regional Climate Assessment,29 which was the regional contribution to the third U.S. National Climate Assessment. The Pacific Islands Regional Climate Assessment was a collaborative effort engaging federal, state, and local government agencies, NGOs, academia, businesses, and community groups to inform and prioritize their activities in the face of a changing climate (Keener et al., 2012). Three technical workshops were held between November 2011 and January 2012, and the Regional Climate Assessment was released later in 2012. Most of the funding came from NOAA, through the Pacific RISA, and the Pacific Islands LCC was also a financial contributor. Because the Pacific Islands CSC was in its infancy at the time, it had a small role in the Regional Climate Assessment.

The research emphases of each entity are somewhat distinct and evolving. The Pacific Islands region’s LCC, CSC, and RISA all share an interest in the physical drivers of change, including sea level rise, ocean wave characteristics, and climate downscaling. However, the methods, applications, and partners of the three organizations are justifiably distinct, and to a large degree complementary.

Current Emphases of the Pacific RISA: Research emphases include

- Regional climate modeling. Techniques using Global Climate Models (GCMs) to generate future climate projections may be of less value over small islands, which are too small to be represented as land in the GCMs. The Pacific RISA supports the use of the Hawaii Regional Climate Model (HRCM) to generate high-resolution climate data for the Hawaiian Islands, Guam, and American Samoa at spatial resolutions as fine as 1 km, a spatial scale necessary to take into account steep topography and diverse microclimates.

- Future groundwater recharge. Using HRCM projections, Pacific RISA partner researchers at the USGS Pacific Islands Water Science Center and the University of Hawaii Water Resources Research Center used calibrated soil–water balance models for the island of Maui to calculate ground-

___________________

24 See http://cpo.noaa.gov/Partnerships/International/TheNorthAmericanClimateServicesPartnership%28NACSP%29_b/RioGrandeRioBravoRegionalPilotArea.aspx; http://www.climas.arizona.edu/blog/notes-field-preparing-climate-change-along-us-mexico-border.

25 See https://accap.uaf.edu/about.

26 See http://pnwcirc.org.

27 See http://southernrockieslcc.org/about-srlcc/science-workgroup.

28 See http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/PICSC/symposium.php; http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/PICSC/news/Review_Symposium.pdf.

SOURCES: http://cpo.noaa.gov/ClimatePrograms/ClimateandSocietalInteractions/RISAProgram/RISATeams.aspx; https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/55b943ade4b09a3b01b65d78.

-

recharge under future land and water management scenarios.

- Land-use and hydrology scenario development. To ensure that results from climate and hydrological models address the needs of Maui and state-level decision makers, Pacific RISA researchers worked with stakeholders to generate a set of feasible future Maui land-use scenarios relevant to groundwater resource management. Land-use maps represent future management decisions and provide the spatial environment across which groundwater recharge is calculated under future climate conditions.

- Regional network maps. To map flows of climate information and identify key hubs and potentially isolated groups in the greater Pacific Islands region, Pacific RISA researchers tracked communications patterns across different sectors and countries. Survey analysis of more than 300 climate change professionals revealed network connectedness and perceived community resiliency, climate change risk, and sense of community.

Current Emphases of the Pacific Islands LCC: Research emphases include

- Mapping potential ranges of native species and invasive species under future temperature and precipitation projections;

- Leading vulnerability assessments for rare species, native ecosystems, and keystone species;

- Predicting future potential community composition within protected areas under different climate scenarios;

- Identifying potential corridors linking present and future habitat;

- Recommending conservation and acquisition priorities based on future climate and sea level; and

- Developing adaptation strategies to protect biodiversity and cultural heritage across the Pacific.

Current Emphases of the Pacific Islands CSC: Research emphases include

- High-resolution projections of future climate, sea level, and shoreline/inundation;

- Estimates of low flow in ungaged streams;

- Understanding and predicting vegetation change and management thereof; and

- Coral reefs and other seascapes.

Consideration of Overlaps: As the above lists indicate, the Pacific Islands LCC, CSC, and RISA research is mostly complementary, with one exception: All three entities have funded projects on regional climate modeling for Hawaii and the Pacific Islands. However, from evidence available on the three programs’ websites, this work was started by simulating climate in Maui with funding from the Pacific RISA because of a specific interest in island water issues. Funding from the Pacific Islands LCC and CSC allowed researchers to apply the modeling framework to other islands in Hawaii and beyond. The committee noticed in at least one case that the Pacific Islands LCC and CSC funded projects that appear to be nearly identical, giving the impression that the same work was funded twice and suggesting that coordination could still be improved.

Southeastern United States

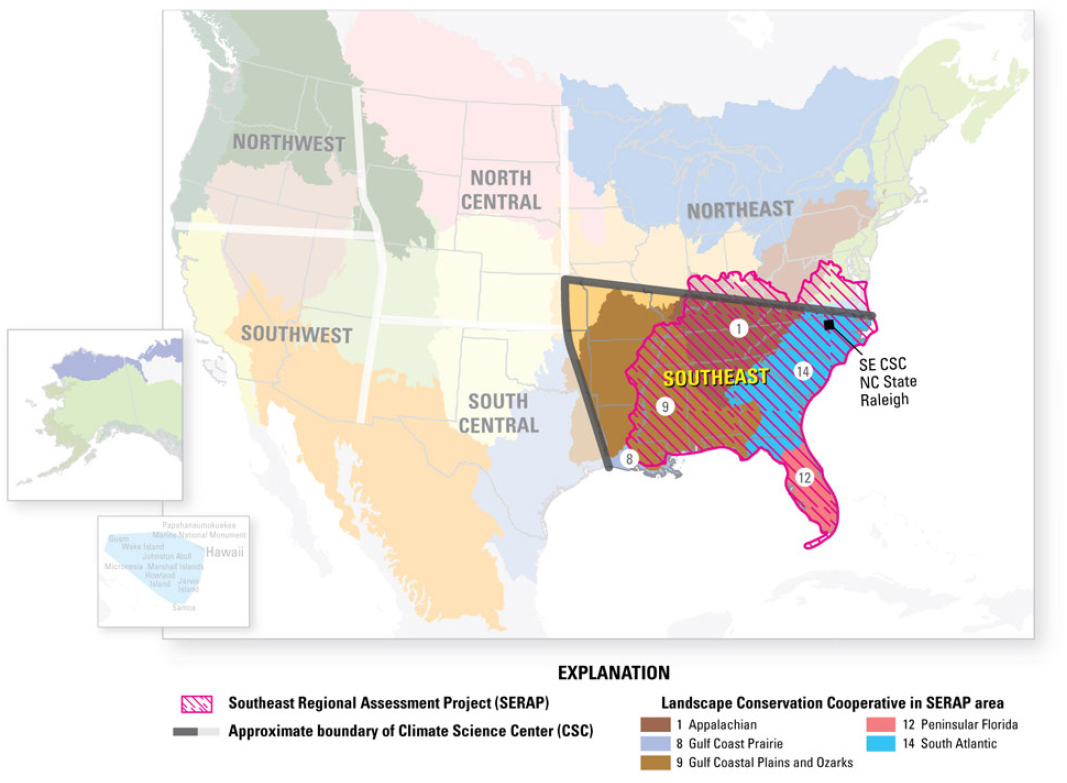

In contrast to the Pacific Islands, the geographic boundaries of programs in the Southeast do not align. The geographic extent of the Southeast CSC (see Figure 5.6) includes all or parts of three RISAs (Carolinas RISA, Southeast Climate Consortium,30 and Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program), and six LCCs (Appalachian, Gulf Coastal Plains and Ozarks, Gulf Coast Prairie, Peninsular Florida, South Atlantic, and Caribbean).

In the Southeast, the RISAs appear to be less involved with LCCs and the Southeast CSC than in the Pacific Islands. This should not be interpreted as a criticism; there appear to be strong and valid institutional and historical reasons for this separation. For instance, the Southeast Climate Consortium focuses on agriculture and on climate projections in the range of 1–12 months, a research focus and time horizon that the CSCs and LCCs are not undertaking.

Careful examination of the complete list of funded projects and activities by the Southeast CSC and the six LCCs revealed several projects with similarities. Specifically, seven projects provided variations of future climate projections, and four on the topic of sea level rise and associated saltwater habitat (marshes, mangroves). However, on closer examination, it became apparent that the seven climate-related projects are complementary. They produce different products over different geographic domains using, generally, different but application-appropriate techniques. As in the previous case study, the committee found that the Southeast CSC and one LCC funded similar projects. This also points to the need for the CSCs and LCCs to closely coordinate their external research-granting processes when the topics overlap.

Evaluation of Overlap and Coordination

The committee noted that the LCC program and other similar programs overlap in some areas. Below, the committee discusses the source of such overlaps; identifies benefits and costs that may be associated with overlaps, especially in the context of the LCCs; and determines that, with adequate coordination and rationale, the current extent of overlap is acceptable.

___________________

30 Since this report entered review, the committee has learned that the Southeast Climate Consortium is no longer currently funded, though it will have an opportunity to apply for future funds again. Therefore, the geographic extent includes all or part of two currently funded RISAs, not three.

SOURCE: https://globalchange.ncsu.edu/secsc/climate-science-centers.

Across the federal government, there are multiple directives to harness different authorities, programs, and funding sources with similar aims—ultimately, to promote conservation at a larger scale. Above, the committee illustrates a variety of such programs across federal agencies. In addition, there are numerous cross-agency efforts focused on either a geographic region (e.g., Chesapeake Bay or Gulf hypoxia; see Gulf hypoxia case study in Appendix B) or a species (e.g., sage-grouse; see case study in Appendix A). As discussed above, there are some similarities in projects, activities, and collaborations supported by LCC programs and other related federal programs.

By design, LCCs are collaborative conservation efforts (see Chapter 2) designed to identify strategic research and conservation priorities among partners, and help leverage funds. As a result, the research funded by LCCs is often collaborative with other agencies. Indeed, such collaborations were specifically encouraged in many LCC- and CSC-sponsored requests for proposals. Therefore, the committee was not surprised to find some overlap with other programs within the FWS, within other DOI bureaus, in other federal agencies, in state agencies, and in the nongovernmental conservation sector. Institutional redundancy and overlap are common in conservation, in natural resource management, and indeed in government organization more generally. The collaborative governance of the LCCs through each steering committee is designed to identify common goals and unmet research needs. The structure of the LCCs is intended to enhance communication and coordination of partners, and to streamline efforts in an increasingly complex field. Through this process, unnecessary overlap and redundancies are likely identified and avoided. Given the U.S. federalist structure, some degree of overlap between state and federal activities is both inevitable and desirable. Even within the federal system (and many state systems) there are significant institutional overlaps and shared regulatory (or management) spaces (Freeman and Rossi, 2012), as well as institutional gaps. In some cases, overlap is the product of federal law, and in this case, the Secretarial Order. Overlaps and redundancies can be beneficial or costly, depending on the context and societal goals.

There are administrative costs associated with redun-

dancy; it is generally more efficient to have a single entity responsible for a mission or a set of objectives than to have multiple entities involved. It may also add confusion, lead to conflict among agencies, and complicate interactions with those seeking to engage in regulated actions. If the institutional landscape is especially complex, it may be difficult either to pinpoint authority or to identify gaps in regulatory coverage (Crowder et al., 2006). Fragmentation may also diffuse responsibility in ways that provide incentives for each of the multiple actors to underplay its own responsibility, avoiding difficult decisions in the hope that other actors will confront them (Buzbee, 2003). It makes planning difficult, because no one entity has a comprehensive view of the managed system. Fragmentation can make learning difficult if there are not well-established lines of communication. It can also make it hard to see, and especially address, the impacts of cumulative or synergistic threats. However, the landscape approach taken by the LCC Network aims to overcome such institutional fragmentation and the associated complexities and inefficiencies. The LCC Network Strategic Plan (LCC, 2014) specifically states that one tactic for creating high-functioning organizational culture for LCCs is to “[i]dentify institutional barriers and stovepipes that inhibit cross-agency collaboration and partnerships and seek to reduce, breakdown, or overcome them.”

The involvement of and overlap among multiple management agencies can also provide benefits; moreover, the negative aspects of redundancy just mentioned may pertain more to regulatory concerns than to the science-management and collaborative priorities of LCCs. As in systems engineering, managing redundancy might reduce the risk of catastrophic failure by allowing one actor to compensate for another’s shortcomings (Landau, 1969). Moreover, institutional separation and overlap can encourage diversity of ideas and approaches, combating the tendency to fall into patterns of “group think,” where assumptions go unexamined and viewpoints tend to converge on an unrealistic extreme (O’Connell, 2006). It can bring to bear the distinct expertise, cultures, and missions of multiple institutional actors. Decentralizing authority also reduces the risk of domination by one particular stakeholder group whose goals diverge from those of the broader policy community (Curtin, 2015). At the most basic level, it is more difficult and costly to influence several agencies than to influence one. In addition, fragmentation allows for differing agency cultures and missions, which in turn should facilitate the zealous pursuit of multiple goals. In a competitive funding environment, scientific or conservation proposals that meet the objectives of multiple organizations (e.g., multiple LCCs or an LCC and a CSC) and show leveraging potential may achieve higher rankings during review than those with narrower support.

The right institutional design question, then, is not whether there is redundancy or overlap, but whether the institutional system as a whole is able to effectively pursue the goals for which it was developed. The answer depends on whether the entities involved are able to communicate, coordinate, and collaborate effectively, not simply on whether there is some overlap or some tension in their missions. The discussion above illustrates generally positive attributes of overlap because there is evidence of communication and coordination to achieve multiple objectives. The steering committee meetings of the LCCs attempt to coordinate across many of the existing programs. Furthermore, workshops, conferences, and training events that are jointly organized and funded can be of higher quality and impact than any one organization could achieve alone. Through personal communications with invited speakers and conversations with stakeholders, the committee learned that multiple LCC participants view the LCCs as a forum for increased and more efficient communication among stakeholders who often come from multiple states and represent a variety of NGOs, federal and state agencies, tribal organizations, and other partnerships. Further, multiple participants described the LCCs as avenues for building relationships, fostering future partnerships, increasing trust, providing learning opportunities, and enhancing technical capacity.

However, coordination among the LCCs and other programs requires staff resources that some of the partners and stakeholders might lack. The committee learned from invited speakers as well as from conversations with stakeholders that a major challenge to evaluation of the LCC Network is the number of collaborative efforts already under way (e.g., by the Joint Ventures, Western Governors’ Association, the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, and AFWA). Despite the fact that many stakeholders recognize that the LCC Network fills an important need, some, in particular state agency representatives, expressed a concern that they do not have sufficient staff capacity to substantially contribute to collaborative efforts. This problem is exacerbated in states with multiple LCCs, and they find themselves having to prioritize among collaborative initiatives.

Moreover, some representatives from state agencies indicated the difficult trade-offs they face in terms of dedicating resources and staff time to directly undertaking projects or participating in one or more LCCs or other partnership efforts. For example, Alaska includes designations in five different LCCs; California, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming each have four LCCs within their borders; and several other states have three. In light of multiple competing demands on capacity, particularly staff time and travel funds, some partners expressed that the cost of engaging in an LCC appear greater than the benefits. Also, because the LCCs are relatively new, many partners have not yet seen the direct benefit to their own priorities or responsibilities. For example, one stated that the scale at which LCCs aim to work (across large landscapes and long timescales) does not match well with state agency objectives, which by their nature must focus on smaller-scale, more immediate concerns. Others saw the LCCs as an added layer of bureaucracy when funds for

science delivery could be administered through preexisting groups and processes.

As the LCCs mature and benefits can be realized and documented, it may become less challenging to justify the staff cost. Some states have already overcome the challenge of participating in multiple LCCs by appointing a single staff person as the designated liaison to all LCCs within a state. Enhancing the opportunities for partners to be actively engaged with the full suite of regional activities that intersect with their missions will be important to the longevity of these efforts. Potential actions could include holding joint meetings between neighboring LCCs or among LCCs and overlapping programs, increasing the capabilities for virtual meetings with real-time interactions, or adjusting boundaries if appropriate to achieving conservation objectives.

CONCLUSIONS

A wide variety of landscape-scale programs exist that are federally funded or initiated. In addition, national associations and regional partnerships have formed that also aim to scale up conservation activities. The diversity of efforts, partnerships, and approaches that the committee reviewed all serve a unique mission or set of goals regarding landscape and habitat conservation. Therefore, the committee concludes that despite some overlap, none of the programs are fully redundant. In fact, many of these efforts are directed at incorporating the landscape approach into the mission of individual resource management agencies. Those efforts that are interagency collaborations largely focus on a smaller geographic region or on a limited number of target species.

Among this large number of programs, there are only a few other landscape-scale programs that combine science delivery with Landscape Conservation Design. Even within this sub-set of science delivery programs, LCCs have a distinct niche in that they identify and prioritize conservation science needs broadly; fund and otherwise support research projects that address these needs; and ensure that the results and products derived from these projects can apply to conservation efforts. They also operate regionally across the entire nation and across borders with Mexico and Canada, and they are not limited in scope to a few target species within a landscape-scale approach. Furthermore, the LCCs aim to develop a nationwide network of partnerships that play an important role working across jurisdictional boundaries and developing an integrated approach to conservation at the landscape scale. Although there is some overlap, the committee concludes that the extent of overlap is acceptable, given that there is usually a good rationale for the redundancy and good coordination with the overlapping partners. LCCs differ significantly in governance, geographic extent, mission, and activities from these other programs presented in this chapter, and hence are not fundamentally duplicative.

Of the programs reviewed, only the Joint Ventures and the CSCs appear to have some potential for redundancy that might need mitigation (see recommendations below). The committee found sufficient coordination between the NOAA RISAs and the LCCs, given different heritages, agency mandates, and governance structures. LCCs appear to benefit from the RISAs’ long history, greater focus on social science and human communities, and capability of producing training events.

The CSCs and LCCs were initiated by Secretarial Order No. 3289 and intended to be complementary. According to their respective strategic plans, the CSCs aim primarily to develop science and the LCCs to develop strategic conservation priorities, Landscape Conservation Designs, and applied science to inform the conservation priorities. However, based on the committee’s review of funded projects, both entities aspire to fund science, develop tools, and translate research for decision makers. Given that research priorities are developed for both the LCCs and CSCs by a committee of resource managers and other partners, it is not surprising that the resulting research might be similar and cause potential redundancies.

Recommendation: The LCC and CSC programs should be more clearly delineated. They should explicitly state how their research efforts differ and how they complement each other, identify and build on existing examples of coordination across the network, and make adjustments as appropriate. At the regional scale, LCC coordinators and CSC federal directors should coordinate their activities, including calls for proposals, as much as possible to avoid duplication of effort.

By design, the Joint Ventures and LCCs are both very similar FWS programs. Once the LCCs develop clear strategic priorities and focus on target species or some particular priorities, they will likely develop their own identity and will become more clearly distinguishable from the Joint Ventures. Despite the recognized need and unique niche for these multiple landscape conservation partnerships, the number of such efforts poses significant challenges to some partners whose active engagement is critical to achieving success (both for the LCCs and related programs). In particular, state agencies might not have sufficient staff resources to actively participate in all partnerships and will have to prioritize which partnerships are most likely to contribute to their own priorities.

Recommendation: DOI should review the landscape and habitat conservation efforts, especially the Joint Ventures and the LCCs, to identify opportunities for improved coordination between these efforts. Special consideration should be given to the limited capacity of state agency partners to participate in multiple efforts simultaneously.

Lastly, the committee was asked to consider “what may be gained or lost by consolidating [these FWS programs] in the LCC program.” The committee concludes based on its analysis above that none of the programs would benefit from consolidation given their distinct roles in addressing the nation’s conservation challenges.

This page intentionally left blank.