5

Preventive Interventions

The research on bullying prevention programming has increased considerably over the past 2 decades, which is likely due in part to the growing awareness of bullying as a public health problem that impacts individual youth as well as the broader social environment. Furthermore, the enactment of bullying-related laws and policies in all 50 states has drawn increased focus on prevention programming. In fact, many state policies require some type of professional development for staff or prevention programming related to bullying (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2015; Stuart-Cassel et al., 2011). Despite this growing interest in and demand for bullying prevention programming, there have been relatively few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) testing the efficacy or effectiveness of programs specifically designed to reduce or prevent the onset of bullying or offset its consequences on children and youth (Bradshaw, 2015; Jiménez-Barbero et al. 2016). Moreover, the much larger body and longer line of research focused on aggression, violence, and delinquency prevention has only recently begun to explore program impacts specific to bullying. The focus of that research has typically been on broader concepts, such as aggression, violence, delinquency, externalizing problems, etc. Therefore, it is quite possible that there are several violence or aggression prevention programs that have substantial effects on bullying, but there is currently too little data available from most violence prevention studies that employ RCT designs to formulate a conclusion regarding impacts on bullying specifically (Bradshaw, 2015).

In this chapter, the committee summarizes the current status of bullying prevention programming, while acknowledging both gaps in the extant literature and opportunities for future research. The committee first focuses

more narrowly on bullying prevention and intervention programming for which there are data specifically on bullying behaviors; greater emphasis is placed on RCTs, as compared to nonexperimental, correlational, or descriptive studies. The committee then considers the broader literature on other youth-focused violence prevention and intervention programming, with particular attention to potential conceptual or measurement overlap with bullying, since such models may hold promise for reducing rates or effects of bullying (Bradshaw, 2015; Hawkins et al. 2015). Although the committee was intentionally inclusive of the larger body of prevention programming literature, it acknowledges the caveats of such a broad focus, as findings from other violence prevention programs may not always generalize to bullying-specific outcomes (e.g., Espelage et al., 2013). Nevertheless, this review is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all evidence-based approaches to bullying or youth violence prevention; rather, the committee highlights particular models and frameworks for which there is a strong or emerging line of RCT studies suggesting promise for preventing or offsetting the consequences of bullying.

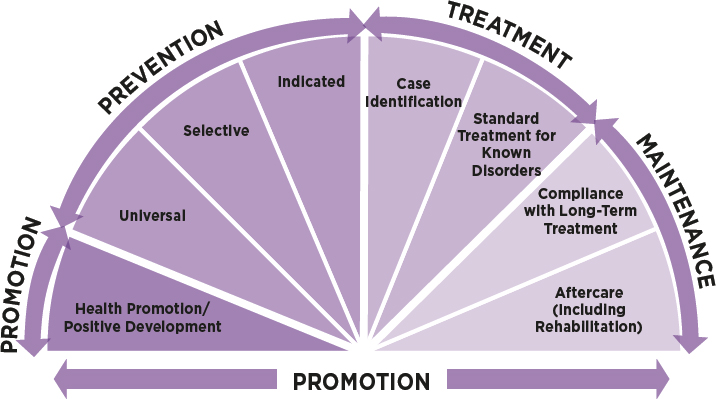

In an effort to organize the vast and somewhat disparate lines of prevention literature, the committee adopted the National Research Council’s public health model of mental health intervention (Institute of Medicine, 1994) as a framework for conceptualizing the various programs and models across increasing levels of intensity (see Figure 5-1).

SOURCE: Adapted from Institute of Medicine (1994, Fig. 2.1, p. 23).

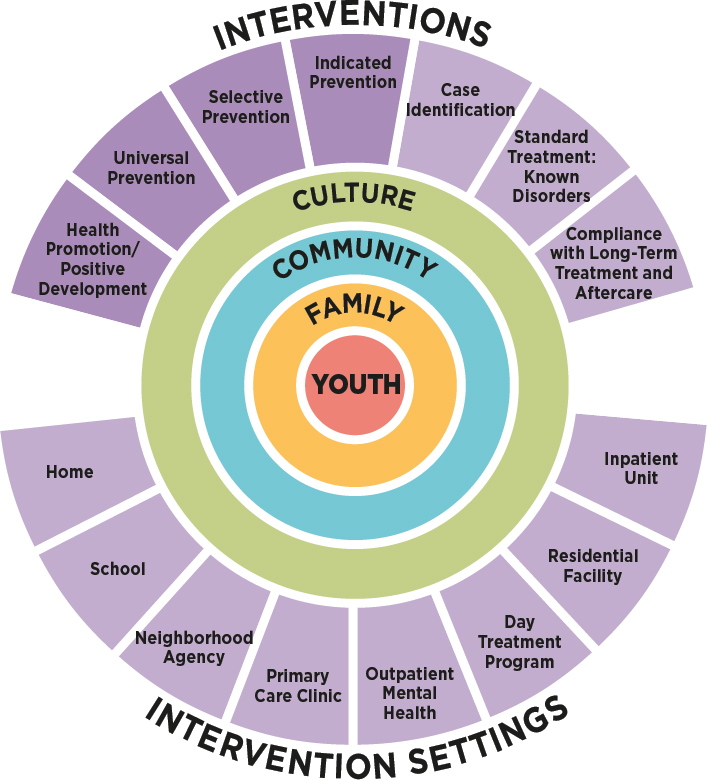

SOURCE: Adapted from National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2009, Fig. 4-1, p. 73).

This model includes three levels of prevention programming (i.e., universal, selective, and indicated), which are preceded by promotion-focused programming and followed by treatment and maintenance (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). Mental health promotion has been recognized as a key component of the mental health intervention continuum (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). Although prevention programming can occur in multiple settings and ecological contexts (see Figure 5-2; also Espelage and Swearer, 2004; Swearer

et al., 2010; Weisz et al., 2005), the majority of research has been conducted within schools. As a result, the committee made an effort to also provide examples of programs that occur in settings other than school, even when the literature base was thinner as it relates to bullying-specific programming and/or outcomes. After summarizing various research-based prevention frameworks and programs, the committee concludes by highlighting lessons learned from the extant research as it relates to critical features of bullying prevention programming and identifying future research directions related to bullying prevention programming.

MULTI-TIERED PREVENTION FRAMEWORK

An increasingly common approach to the prevention of emotional and behavioral disorders is the three-tiered public health model that includes universal, selective, and indicated preventive interventions, as illustrated in Figure 5-1 (Institute of Medicine, 1994; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009; Weisz et al., 2005). Similar frameworks have been proposed or articulated to conceptualize a multi-tiered system of supports (for a review, see Batsche, 2014). Although this continuum of preventive interventions can be applied to many behavioral, educational, mental health, and physical health problems, this report considers it primarily through the lens of bullying prevention among youth.

The Three Tiers

Specifically, universal prevention programs are aimed at reducing risks and strengthening skills for all youth within a defined community or school setting. Through universal programs, all members of the target population are exposed to the intervention regardless of risk for bullying. Using universal prevention approaches, a set of activities may be established that offers benefits to all individuals within that setting (e.g., school). Examples of universal or Tier 1 preventive interventions include social-emotional lessons that are used in the classroom, behavioral expectations taught by teachers, counselors coming into the classroom to model strategies for responding to or reporting bullying, and holding classroom meetings among students and teachers to discuss emotionally relevant issues related to bullying or equity. Universal interventions could also include guidelines for the use of digital media, such as youth’s use of social network sites.

Most of the bullying prevention programs that have been evaluated with RCT designs have employed a universal approach to prevention (Ttofi and Farrington, 2011; Jiménez Barbero et al., 2016). Although universal bullying prevention programs are typically aimed at having effects on youth, they may also yield benefits for the individuals implementing the

programs. For example, recent findings from a RCT of a social–emotional learning and behavior management program indicated that the program substantially affected the teachers who implemented the program, as well as affecting the students (Domitrovich et al., 2016). Similarly positive effects were observed in a randomized trial of a schoolwide Positive Behavior Support model, where implementation of the model demonstrated significant impacts on the staff members’ perceptions of school climate (Bradshaw et al., 2009a). Consistent with the social-ecological model, these effects may be either direct—through the professional development provided to the teachers—or indirect through the improved behavior and enhanced organizational context of the setting in which the program is implemented. These types of secondary impacts on the broader school or community environment also likely occur in universal bullying prevention programs, many of which are intended to reduce bullying in conjunction with improving school climate (Bradshaw, 2013).

Most school-based bullying prevention programs would fall under the universal category of largely preventive interventions, with limited articulation of specific programs, activities, or supports for students not responding adequately to the universal model. Even if the programs focus on the whole school or climate/culture changes, they often take the perspective that a universal approach is the most important and potentially most effective intervention because all children can benefit from attempts to enhance school climate, change attitudes or awareness about bullying, reduce aggressive behavior, or improve related social skills or behavior. Furthermore, some universal programs follow the assumption that all students are considered to be at risk at some level for bullying behavior, either as perpetrators, targets, or bystanders (Rigby and Slee, 2008). In fact, there is a growing recognition that universal prevention programs do not equally benefit all individuals; rather, evidence is emerging that universal prevention programs may actually be more effective for higher risk students than those traditionally conceptualized as low risk (Bradshaw et al., 2015; Eron et al., 2002; Kellam et al., 1994). As a result, there is a growing trend in prevention research to explicitly examine variation in responsiveness to universal prevention programs in order to better understand which youth may be most affected by a particular model (Kellam et al., 1994; Lanza and Rhoades, 2013). This may also improve understanding of why some effect sizes of universal prevention programs are relatively modest when they are averaged across a large population, as a broader population may have a relatively low base rate for engaging in the behavior (Biglan et al., 2015). On the other hand, investing in prevention on a national level has the potential to produce significant and meaningful behavior change for larger populations of youth across a broad array of outcomes, not just outcomes related to

bullying behavior (Biglan et al., 2015; Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015).

The next level of the tiered prevention model is referred to as selective preventive interventions. These may either target youth who are at risk for engaging in bullying or target youth at risk of being bullied. Such programs may include more intensive social-emotional skills training, coping skills, or de-escalation approaches for youth who are involved in bullying. Consistent with a response-to-intervention framework, these Tier 2 approaches are employed to meet the needs of youth who have not responded adequately to the universal preventive intervention (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009).

The third tier includes indicated preventive interventions, which are typically tailored to meet the youth’s needs and are of greater intensity as compared to the two previous levels of prevention. Indicated interventions incorporate more intensive supports and activities for those who are already displaying bullying behavior or have a history of being bullied and are showing early signs of behavioral, academic, or mental health consequences. The supports are usually tailored to meet the needs of the students demonstrating negative effects of bullying (Espelage and Swearer, 2008); they typically address mental and behavioral health concerns, often by including the youth’s family. Such programs may also leverage expertise and involvement of teachers, education support professionals, school resource officers, families, health care professionals, and community members, thereby attempting to support the participating youth across multiple ecological levels. While a number of selective and indicated programs have demonstrated efficacy for a range of youth behavioral and mental health problems (for a review see National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009), there has been considerably less research on selective and indicated prevention programs specific to bullying (Swearer et al., 2014).

Integrating Prevention Programs across the Tiers

Consistent with the public health approach to prevention (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009) and calls for multi-tier or multidisciplinary approaches to prevention, there is an increasing interest in layering components “on top of” or in combination with the universal intervention to address factors that may place youth at risk for being targets or perpetrators of bullying (universal plus targeted interventions). These combined programs often attempt to address at the universal level such factors as social skill development, social-emotional learning or self-regulation, which are intended to also reduce the chances that youth would engage in bullying or reduce the risk of further being bullied (Bradshaw, 2013, 2015; Merrell et al., 2008; Ttofi and Farrington, 2011; Vreeman and

Carroll, 2007). These combined programs are often characterized as universal, whole school, or climate/culture changing programs that may have additional “benefits” for perpetrators or targets (e.g., help them be more effective in coping with the stress of bullying). However, few have easily identifiable components that specifically target youth at risk for involvement in bullying behavior or those already identified as perpetrators or targets. Therefore much of what is currently known about bullying prevention derives from studies of universal programs, with limited research on selective and indicated models for prevention.

Current research is limited in its ability to specifically tease out the effects of targeted elements embedded in whole-school universal programs (Bradshaw, 2015; Ttofi and Farrington, 2011). For example, evaluators have not been able to assess whether it is the universal or targeted components (or the combination of the two) that leads to reductions in bullying behavior or improvements in social-emotional skills (Ttofi and Farrington, 2011). In fact, few of the truly multi-tiered programs have been evaluated using randomized, controlled esperimental designs to determine whether they are effective or lead to sustained behavior change. Moreover, once a child or youth is identified as a target or a perpetrator of bullying, the individual is often referred to mental health or behavioral health services providers in the community—in part because few school-based mental health professionals are available to provide these specialized services (Swearer et al., 2014).

In summary, despite calls for a layered public health approach to bullying prevention or calls for multicomponent, multilevel programs (Leff and Waasdorp, 2013), few studies of school-based bullying prevention programs have simultaneously evaluated both universal and targeted components (Bradshaw, 2015). Although many researchers encourage the use of a multi-tiered approach to address bullying, and there is conceptual research supporting the full integration of preventive interventions (Bradshaw, 2013, 2015; Espelage and Swearer, 2008; Hawley and Williford, 2015; Hong and Espelage, 2012; Swearer et al., 2012), relatively few large-scale RCT studies have examined the combined and tier-specific effects of multi-tiered programs on bullying. Yet, integrating the nested levels of support into a coherent, tiered framework could also reduce burden and increase efficiency of implementation (Bradshaw et al., 2014a; Domitrovich et al., 2010; Sugai and Horner, 2006).

PREVENTION PROGRAMS SPECIFICALLY IMPLEMENTED TO REDUCE BULLYING AND RELATED BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

The sections that follow focus on the available efficacy and effectiveness research that has examined different bullying prevention programs, the vast majority of which have been implemented at the universal level and within schools. The committee first considers the evidence for the effectiveness of universal programs, many of which are whole-school efforts that may include some elements directed to youth at risk for bullying or those already engaged in bullying behaviors.1 The committee also reviews the effectiveness of specific selective or indicated prevention programs, many of which were designed more broadly for youth with behavioral or mental health problems, rather than specifically for bullying.

The committee considered the broader literature on programs aimed at reducing youth aggressive behavior and those aimed at improving emotional and behavioral problems among youth. While most of these programs were not originally developed to address bullying behavior specifically, one may still learn much from them about means to reduce bullying-related behavior, or they may provide clues about how to improve resilience, social competence, or problem-solving skills that may lead to reductions in bullying perpetration or being bullied. In some instances, the committee has drawn

___________________

1 Clinicians and policy makers define efficacy trials as trials that determine whether “an intervention produces expected results under ideal circumstances” and effectiveness trials as trials that “measure the degree of beneficial effect under ‘real world’ clinical settings” (Gartlehner et al., 2006).

upon literature from related fields, such as trauma exposure or research on how families can promote emotional resilience to being a target of bullying (Bowes et al., 2010). Few of these studies, however, have assessed or examined the impact of these interventions on behaviors specific to bullying. Rather, they may assess behaviors such as fighting, threats, violence, aggressive, or delinquent behavior. If one takes the position that most bullying can be characterized as aggressive behavior but not all aggressive or violent behavior meets the narrower definition of bullying (Farrington and Ttofi, 2011; Finkelhor et al., 2012; Leff and Waasdorp, 2013), then perhaps there are lessons to learn from interventions that have shown reductions in aggression and violence or improvements in social skills, even if bullying behavior was not the primary focus of the intervention. The same thinking applies to studies of peer victimization in that while being bullied may be characterized as a form of victimization, not all victimization by peers would be characterized as bullying, particularly with respect to the criteria of repeated targeting or a power imbalance (Finkelhor et al., 2012).

Another reason the committee has considered the broader violenceprevention literature is that bullying often co-occurs with other behavioral and mental health problems, including aggression and delinquent behaviors (Bradshaw et al., 2013a; Swearer et al., 2012), and the risk factors targeted through preventive interventions are often interrelated. For example,

aggressive youth are more likely to be rejected by their peers, to have associated academic problems (Nansel et al., 2003), or to experience higher rates of family discord or maltreatment (Shields and Cicchetti, 2001). Further, many preventive interventions seek to enhance positive or prosocial behaviors or improve social competence, in addition to reducing negative behaviors such as aggression and fighting (Embry et al., 1996; Flannery et al., 2003).

For example, a meta-analysis of school-based mental health promotion programs found that they can improve social-emotional skills, prosocial norms, school bonding, and positive social behavior, as well as result in reduced problem behaviors, such as aggression, substance use, and internalizing symptoms (Durlak et al., 2007; Durlak et al., 2011). An improvement in competence and social problem-solving skills may lead to reductions in bullying perpetration even if that was not the intended outcome of the intervention. Other studies have demonstrated improvements in youth coping skills and stress management (Kraag et al., 2006), which can be helpful to children who are bullied even if such children were not the original population targeted by the intervention. In summary, many school and community-based programs were not originally designed to specifically reduce bullying, but because they target related behaviors, they may provide valuable lessons that can inform efforts related to bullying prevention.

Summary of the Available Meta-Analyses

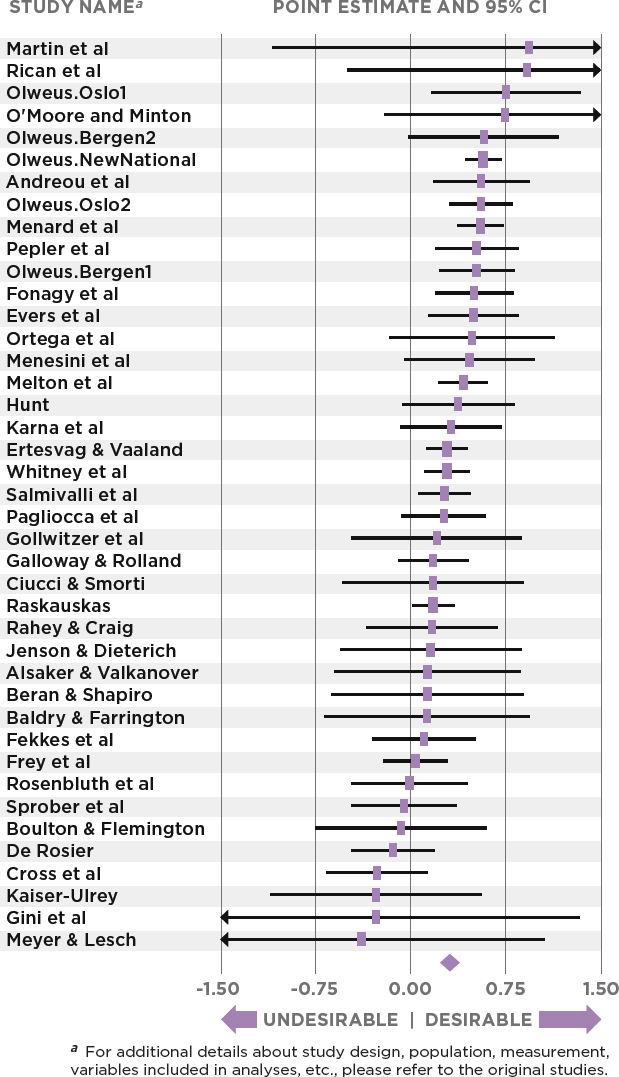

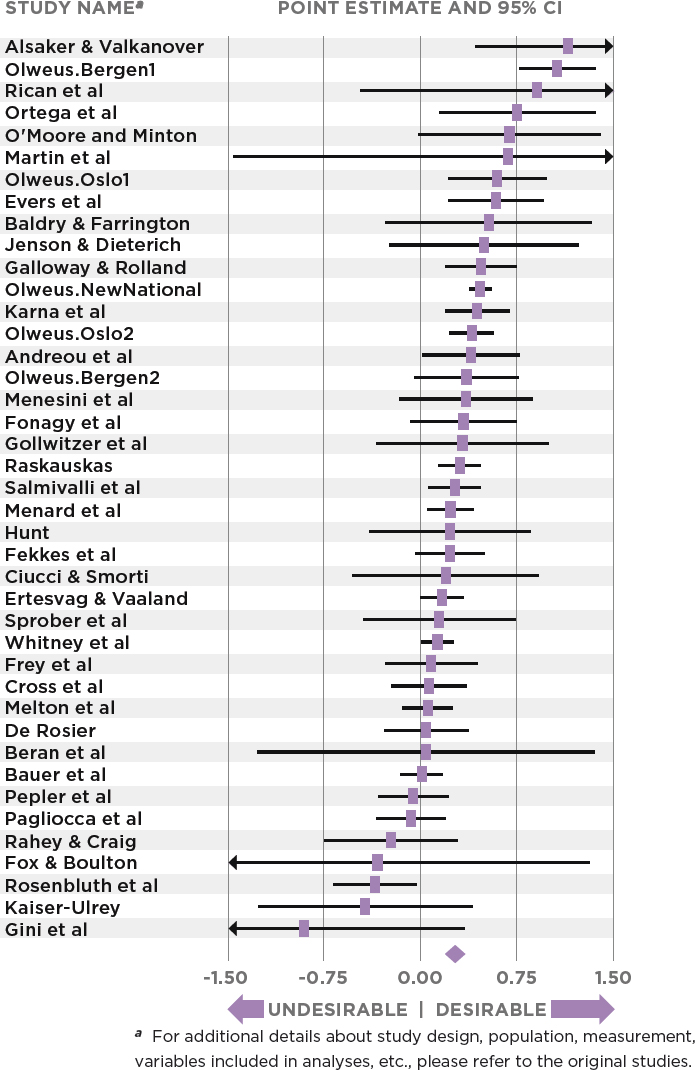

A number of recent meta-analyses have been conducted in an effort to identify the most effective and promising approaches within the field of bullying prevention; for a review of the meta-analyses see Ttofi and colleagues (2014). The most comprehensive review conducted to date was by Ttofi and Farrington (2011), who applied the Campbell Systematic Review procedures in reviewing 44 rigorous program evaluations and RCTs. The majority of these studies were conducted outside the United States or Canada (66%), and over a third of the programs were based in part on the work of Olweus (1993). Ttofi and Farrington (2011) found that the programs, on average, were associated with a 20-23 percent decrease in perpetration of bullying, and a 17-20 percent decrease in being bullied, as illustrated in Figures 5-3 and 5-4.2

As in other reviews and meta-analyses (Bradshaw, 2015; Leff and Waasdorp, 2013), Farrington and Ttofi (2009) concluded that in general the

___________________

2 The committee includes details of studies where possible, in particular if the study employed a RCT design and where effect sizes are reported or control groups were used. We encourage the reader to refer to the original studies for additional details about study design, population, measurement, variables included in analyses, etc.

most effective programs are multicomponent, schoolwide programs that reduce bullying and aggression across a variety of settings. However, as noted previously, these multicomponent programs are not always multi-tiered in the context of the public health model; rather, they may have multiple complementary program elements that all focus on universal prevention, such as a combination of a whole-school climate strategy coupled with a curriculum to prevent bullying or related behaviors. Furthermore, the designs of the studies precluded the researchers from isolating which program elements accounted for the program impacts. Nevertheless, Farrington and Ttofi (2009) concluded that parent training, improved playground supervision, disciplinary methods, school conferences, videos, information for parents, classroom rules, and classroom management were program components associated with a decrease in students being bullied.

The whole-school bullying prevention programs (mostly based on or modeled after the extensively studied Olweus Bullying Prevention Program model, which aims at reducing bullying through components at multiple levels) also generally demonstrated positive effects, particularly in schools with more positive student-teacher relationships (Richard et al., 2012). In general, significant intervention effects have been demonstrated more often for programs implemented in Europe (Richard et al., 2012) and Scandinavian countries (Farrington and Ttofi, 2009; Salmivalli, 2010) than in the United States (also see Bradshaw, 2015). Some researchers and practitioners have suggested that interventions implemented outside the United States may be more successful because they involve more homogeneous student samples in schools that are more committed to implementing programs as intended (Evans et al., 2014), compared with student samples and schools’ commitment in the United States. Competing demands on student and teacher time, such as standardized testing, also limit U.S. teachers’ perceived ability to focus on social-emotional and behavioral activities, as compared with traditional academic content. The challenges in designing and delivering effective bullying prevention programs in the United States may also include the greater social and economic complexities of U.S. school populations, including greater income disparities and racial/ethnic heterogeneity.

The meta-analyses, most notably the Ttofi and Farrington (2011) review, noted variation in program effects based on study design, as has been shown for most such intervention programs. For example, large-scale effectiveness studies (i.e., studies of taking an intervention program to scale) did not produce effects as strong as those in more tightly controlled efficacy studies, where the program is often administered with greater support and researcher influence (Bradshaw, 2015; Ttofi and Farrington, 2011). Similarly, the effects generally were stronger in the non-RCT designs than in the RCTs, suggesting that the more rigorous the study design, the smaller the effect sizes (Farrington and Ttofi, 2009). Moreover, as has been shown in

several other studies across multiple fields (e.g., Domitrovich et al., 2008), poor implementation fidelity has been linked with weaker program outcomes (also see Durlak et al., 2011).

Another important finding from the Ttofi and Farrington review was that, generally speaking, there are more school-based bullying prevention programs that involve middle-school youth than those that target youth of high school age. Of the programs that have been evaluated with RCT designs, the observed effects were generally larger for older youth (ages 11-14) than for younger children (younger than age 10) (Farrington and Ttofi, 2009; Ttofi and Farrington, 2011). However, this effect has not been consistent across all programs and all studies, as there is compelling developmental research suggesting that the earlier one intervenes to prevent behavior problems, the more effective the intervention is (Kellam et al., 1994; Waasdorp et al., 2012). Unpacking this finding is likely to be complicated because different programs are often used at different age ranges, thereby confounding the child’s age with the program used. However, more recently, some programs that were originally developed for a particular age group have been adapted for youth of a different age range (e.g., Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies, Second Step, Coping Power; Olweus Bullying Prevention Program). Implementations of these programs span multiple age groups, with specific curricular or program activities that are developmentally appropriate for the target population (e.g., to address different developmental needs for a third grader than for an eighth grader).

Other meta-analyses of school-based bullying intervention programs have not been as positive as the Ttofi and Farrington (2011) review (e.g., Merrell et al., 2008; Vreeman and Carroll, 2007). Some of these mixed findings may be due to different inclusion criteria, such as where the study was conducted (e.g., in the United States or Europe) or who conducted it (i.e., the program developer or an external evaluator). For example, Merrell and colleagues (2008) reviewed 16 studies of over 15,386 kindergarten through grade 12 (K-12) students in six different countries from 1980 through 2004. They concluded that the majority of outcomes were neither positive nor negative and generally lacked statistical significance one way or the other (they found a meaningful positive average effect on bullying for about one-third of all outcomes). They further concluded that programs are much more likely to show effects on attitudes, self-perceptions, and knowledge than on bullying behavior. Only one of the reviewed studies specifically included an intervention for at-risk students; a program that assigned social workers to the primary school building to work with students at risk for perpetrating or being targets of bullying (Bagley and Pritchard, 1998). Bagley and Pritchard (1998) assessed student self-reports of bullying incidents and showed significant declines in bullying among students who received intervention services from social workers. Merrell and his col-

leagues (2008) did not weight the 16 studies in the meta-analysis for sample size, degree of experimental rigor, or threats to validity when they computed effect sizes within the individual research studies. Overall, however, they concluded that while some intervention studies had positive outcomes, these were mostly for attitudes and knowledge rather than improving (lessening the frequency of) youth self-reports of being perpetrators or targets of bullying (Merrell et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2004).

Vreeman and Carroll (2007) also conducted a systematic review of bullying preventive interventions, some of which combined programs across the tiers. They found that whole-school approaches with teacher training or individual counseling did better than curricular-only approaches. Of the 26 studies that met their inclusion criteria, only four included targeted interventions involving social and behavioral skills groups for children involved in bullying as perpetrators (Fast et al., 2003; Meyer and Lesch, 2000) and two targeted youth who were victims of bullying (DeRosier, 2004; Tierney and Dowd, 2000). According to Vreeman and Carroll (2007), three of the four studies focused on youth in middle school (sixth through eighth grade) and one examined third grade students. The only social skills training intervention that showed clear reductions in bullying was the study of third grade students. The other three studies of older youth produced mixed results.

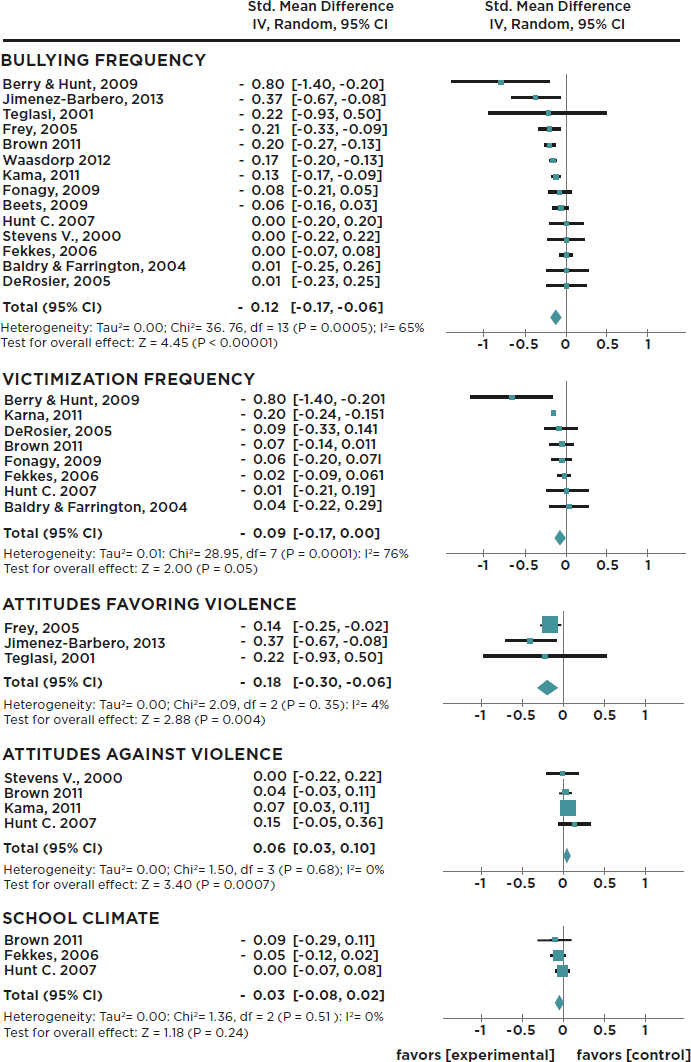

Another more recent meta-analysis of bullying prevention programs by Jiménez-Barbero and colleagues (2016) examined a range of effects of 14 “anti-bullying” programs tested through RCTs, comprising 30,934 adolescents ages 10-16. All studies were published between 2000 and 2013. They examined not only bullying frequency (ES = 0.12) and victimization frequency (ES = 0.09), but also attitudes favoring bullying or school violence (ES = 0.18), attitudes against bullying or school violence (ES = 0.06), and school climate (ES = 0.03). See details of the individual studies below in Figure 5-5. This study was considerably smaller in scale than the Ttofi and Farrington (2011) meta-analysis, in large part because of stricter inclusion criteria. Furthermore, on average, these effect sizes were smaller than observed in the Ttofi and Farrington (2011) study. Because of the smaller sample size, it is difficult to formulate conclusions based on specific components (e.g., family, teacher) or youth subgroups (e.g., age of students). Taken together, the meta-analyses provide evidence that the effect sizes of universal programs are relatively modest. Yet these effects are averaged across a full population of youth; selective and indicated prevention approaches, which focus on youth more directly involved in bullying, will likely yield larger effect sizes, as has been seen in other studies of violence prevention programming (discussed later in this chapter).

In contrast to the somewhat mixed findings on interventions specifically for bullying prevention, the larger body of universal youth violence preven-

NOTE: For additional details about study design, population, measurement, variables included in analyses, etc., please refer to the original studies.

SOURCE: Adapted from Jiménez-Barbero et al. (2016, Fig. 2, p. 171).

tion programming has generally had more favorable results, particularly for preschool and elementary school children (Sawyer et al., 2015; Wilson and Lipsey, 2007). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of school-based violence prevention programs (most that did not specifically address bullying behaviors) have shown many to be effective at reducing aggressive behavior and violence (Botvin et al., 2006; Durlak et al., 2011; Hahn et al., 2007; Mytton et al., 2002). Whereas some of the reviews of programs focused on bullying have reported greater effects for older students in middle or secondary schools versus students in primary schools (Mytton et al., 2002; Ttofi and Farrington, 2011), the programs focused on aggression and social competence have shown greater effects for younger children (Kärnä et al., 2011a). One factor may be variations in focus, such as reviews that cover secondary prevention trials for those at risk for aggression and violence (Mytton et al., 2002) versus reviews that include universal and whole school violence prevention programs (Hahn et al., 2007). For example, a review of violence prevention programs by Limbos and colleagues (2007) found that about one-half of 41 intervention studies showed positive effects, with indicated interventions for youth already engaged in violent behavior being more effective than universal or selective interventions.

Another comprehensive meta-review of 25 years of meta-analyses and systematic reviews of youth violence prevention programs concluded that most interventions demonstrate moderate program effects, with programs targeting family factors showing marginally larger effects compared to those that did not (Matjasko et al., 2012). Strength of evidence was rated as small, moderate, or strong by the authors using data on reported effect sizes. This meta-review suggested that studies consistently reported larger effect sizes for reduction of youth violent behavior for programs that targeted selected and indicated populations of youth versus universal prevention. The authors also found that programs with a cognitive-behavioral component tended to have larger effect sizes than those without that component or with only a behavioral component (Matjasko et al., 2012). These findings are generally consistent with a recent meta-analysis by Barnes and colleagues (2014), who found that school-based cognitive behavioral interventions were effective (mean ES = −0.23) on reducing aggressive behavior, especially those delivered universally compared with those provided in small group settings (Barnes et al., 2014).

Examples of Universal Multicomponent Prevention Programs to Address Bullying or Related Behavior

As noted above, many schoolwide bullying prevention programs include multiple components, both within and across the three prevention tiers. One such program is the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (Olweus,

2005), which is also the most extensively studied bullying prevention program. It aims to reduce bullying through components at multiple levels, including schoolwide components; classroom activities and meetings; targeted interventions for individuals identified as perpetrators or targets; and activities aimed to increase involvement by parents, mental health workers, and others. Some studies of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program have reported significant reductions in students’ reports of bullying and antisocial behaviors (e.g., fighting, truancy) and improvements in school climate (Olweus et al., 1999). However, some smaller-scale studies of this model produced mixed results (e.g., Hanewinkel, 2004). Although other derivations of Olweus’s model also have demonstrated promise at reducing bullying in North America (e.g., Pepler et al., 2004), these programs were generally more effective in Europe. Farrington and Ttofi (2009) found that programs that were conceptually based on the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program were the most effective, compared to the other programs examined (OR = 1.50 versus OR = 1.31, p = .011).

Another multicomponent and multi-tiered prevention model is Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) (Sugai and Horner, 2006; see also Walker et al., 1996). PBIS aims to prevent disruptive behaviors and promote a positive school climate through setting-level change, in order to prevent student behavior problems systematically and consistently. The model draws upon behavioral, social learning, organizational, and positive youth development theories and promotes strategies that can be used by all staff consistently across all school contexts (Lewis and Sugai, 1999; Lindsley, 1992; Sugai et al., 2002). Through PBIS, staff and students work together to create a schoolwide program that clearly articulates positive behavioral expectations, provides incentives to students meeting these expectations, promotes positive student-staff interactions, and encourages data-based decision making by staff and administrators. The model aims to alter the school environment by creating both improved systems (e.g., discipline, reinforcement, and data management systems) and procedures (e.g., collection of office referral data, training, data-based decision making) in order to promote positive change in student and teacher behaviors (Kutash et al., 2006; Sugai and Horner, 2006). The PBIS model also emphasizes coaching to tailor the implementation process to fit the culture and context of the school. The PBIS framework acknowledges that there is no one-size-fits-all program or model, therefore, coaches work with the schools to collect data in order to identify needs and both local challenges and resources. They subsequently help the school choose the most suitable program to be integrated within the PBIS framework, and they provide support to staff to optimize implementation fidelity.

The PBIS model follows a multi-tiered prevention approach (Institute of Medicine, 1994; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine,

2009), whereby Tier 2 (selective/targeted) and Tier 3 (indicated) programs and supports are implemented to complement the Tier 1 (universal) components (Sugai and Horner, 2006; Walker et al., 1996). Recent randomized effectiveness trials of PBIS, largely focused on the universal, Tier 1 elements, have reported significant effects on bullying and peer rejection (effect sizes ranging from 0.11 to 0.14; see Bradshaw, 2015; Waasdorp et al., 2012), as well as school climate (effect sizes from 0.16 to 0.29; see Bradshaw et al., 2008; Horner et al., 2009), and discipline problems (effect sizes from 0.11 to 0.27; see Bradshaw et al., 2010, 2012, 2015). Other significant effects have been reductions in suspensions and office referrals (ES = 0.27; see Bradshaw et al., 2008, 2009a, 2010; Horner et al., 2009; Waasdorp et al., 2012). Another randomized trial of PBIS combining Tier 1 and 2 supports in elementary schools also demonstrated significant improvements, relative to Tier 1 only, on teacher and student behaviors such as special education usage, need for advanced tier supports, and teacher efficacy to manage student behavior problems (Bradshaw et. al., 2012). An ongoing RCT of PBIS in 58 high schools, which combines other programs at Tiers 2 and 3, is currently under way; the preliminary findings from this trial suggest positive effects on bullying, violence, school climate, and substance use (Bradshaw et al., 2014b).

The KiVa Antibullying Program is another schoolwide, multicomponent program that has demonstrated promising effects. It has been implemented nationally in Finland for students in grades 1 through 9. Its universal elements include activities designed to increase bystander empathy and efficacy, teacher training, and more-targeted strategies for students at risk for or engaged in bullying as perpetrators or victims. It provides classroom training and materials to promote open discussions between teachers and students, peer support for students who are bullied, training for school staff in disciplinary strategies, and informational materials for families to prevent and appropriately respond to bullying. Computer games are also used to help students practice bullying prevention skills.

In their nonrandomized national trial, Kärnä and colleagues (2011a, 2011b) showed that after 9 months of implementation, students in KiVa schools reported lower rates of bullying behavior compared to students in non-intervention control schools. Specifically, victimization rates decreased with age from grade 1 (25.9%) to grade 9 (9.3%), with the largest decrease occurring between grades 1 and 6. Compared to controls, students in the KiVa program reported lower rates of being targeted for bullying (OR = 1.22; 95% CI [1.19, 1.24]) and perpetration of bullying (OR = 1.18; 95% CI [1.15, 1.21]).

Previous evaluations of the KiVa Program have also found the greatest program effects for younger elementary age students (grades 1-6) and smaller effects for middle-school age children (grades 7-9). Generally, pro-

gram effects increased through grade 4 but steadily declined from that point forward. Specifically, KiVa has demonstrated significant impacts on being a perpetrator or a target of bullying behavior among students in grades 4-6 (effect sizes from 0.03 to 0.33; see Kärnä, et al., 2011a, 2011b), as well as for youth in grades 1-9 (odds ratios from 0.46 to 0.79; see Garandeau et al., 2014). In one evaluation of the KiVa Program, Veenstra and colleagues (2014) showed that for fourth to sixth grade students, their perception of teacher efficacy in decreasing bullying was associated with lower levels of peer-reported bullying. They argued that teachers play an important role in anti-bullying programs and should be included as targets of intervention. Ahtola et al., (2012) also found in their evaluation of the KiVa Program that teacher support of the program was positively related to implementation adherence, which in turn contributes to the potential for enhanced program effects. KiVa has only been tested in Europe, although there are currently efforts under way to adapt the model for use in other countries such as the United States.

A recent meta-analysis examining developmental differences in the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs provides some supportive evidence for significant declines in program effectiveness for students in eighth grade and beyond (Yeager et al., 2015). Specifically, Yeager and colleagues examined hierarchical within-study moderation of program effects by age as compared to more typical meta-analytic approaches that examine between-study tests of moderation. Their findings are inconsistent with the findings of Ttofi and Farrington (2009), in which larger program effect sizes (reductions in perpetrating and being a target of bullying) were found for programs implemented with older students (typically defined as students over age 11) compared to younger students.

A number of social-emotional learning programs have also been developed and tested to determine impacts on a range of student outcomes (Durlak et al., 2007, 2011). Some of these models have shown promising effects on aggression and bullying-related outcomes. One such model is Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum. This classroom-based curriculum for children of ages 4-14 aims to reduce impulsive, high-risk, and aggressive behaviors while increasing social-emotional competence and protective factors. The curriculum teaches three core competencies: empathy, impulse control and problem solving, and anger management (Flannery et al., 2005; Baughman Sladky et al., 2015). Students participate in 20-50-minute sessions two to three times per week, in which they practice social skills. Parents can participate in a six-session training that familiarizes them with the content in the children’s curriculum. Teachers also learn how to deal with disruptions and behavior management issues. (Flannery et al., 2005). In one study, children in the Second Step Program showed a greater drop in antisocial behavior compared to those who did not receive the program, behaved less aggressively, and were more likely to prefer prosocial goals

(Flannery et al., 2005; Frey et al., 2005). Other studies of Second Step have demonstrated significant reductions in reactive aggression scores for children in kindergarten through second grade and significant reductions in teacher-rated aggression for the children rated highest on aggression at baseline (Hussey and Flannery, 2007).

In a RCT of 36 middle schools, Espelage et al. (2013) found that students in Second Step intervention schools were 42 percent less likely to self-report physical aggression than students in control schools, with aggression measured as incidents of fighting, but the authors reported that the program had no effect on verbal/relational bullying perpetration, peer victimization,3 homophobic teasing, or sexual violence. In one of the first school-level RCTs of a violence prevention curriculum, Grossman and colleagues (1997) examined, via parent and teacher reports and investigator observation, the effects of the Second Step preventive intervention program on elementary student (second and third grade) aggressive and prosocial behavior. While they did not find changes over time in parent or teacher reports, behavioral observations of students in various school settings showed an overall decrease 2 weeks after the curriculum in physical aggression (–0.46 events per hour, p = .03) and an increase in neutral/prosocial behavior (+3.96 events per hour, p =.04) in the intervention group compared with the control group. One of the recurrent limitations faced by school-level analyses is that measures that have been validated as school-level constructs may not use measures that have only been validated for individual assessment. Similarly, analyses in many studies do not account for the nesting of students within classrooms or schools.

The Good Behavior Game is an elementary school-based prevention program that targets antecedents of youth delinquency and violence. It uses classroom behavior management as a primary strategy to improve on-task behavior and decrease aggressive behavior (Baughman Sladky et al., 2015). Evaluations of the Good Behavior Game in early elementary school have shown it results in reduced disruptive behavior, increased academic engagement time, and statistically significant reductions in the likelihood of highly aggressive children receiving a diagnosis of a conduct disorder by sixth grade, as well as a range of positive academic outcomes (Bradshaw et al., 2009a; Wilcox et al., 2008). The effects were generally strongest among the most aggressive boys, who, when exposed to the program starting in the first grade, had lower rates of antisocial personality disorder when diagnosed as young adults (Petras et al., 2008) and reduced rates of mental health service use, compared to those in the control group (Poduska et al., 2008).

Good Behavior Game has also been tested in combination with other

___________________

3 Peer victimization was assessed using the three-item University of Illinois Victimization Scale (Espelage et al., 2013).

programs, such as Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers (LIFT), which combines school-based skills training with parent training for first and fifth graders. This program is implemented over the course of 21 one-hour sessions delivered across 10 weeks. LIFT uses a playground peer component to encourage positive social behavior and a 6-week group parent-training component. The Good Behavior Game is the classroom-based component of LIFT. LIFT also reduced playground aggression, reduced overall rates of aggression, and increased family problem solving (Eddy et al., 2000; Baughman Sladky et al., 2015).

Raising Healthy Children (Catalano et al., 2003), formerly known as the Seattle Social Development Project (Hawkins et al., 1999), is a multidimensional intervention that targets both universal populations and high-risk youth in elementary and middle school. The program uses teacher and parent training, emphasizing classroom management for teachers and conflict management, problem-solving, and refusal skills for children. Parents receive optional training programs that target rules, communication, and strategies to support their child’s academic success. Follow-up at age 18 showed that the program significantly improved long-term attachment and commitment to school and school achievement and reduced rates of self-reported violent acts and heavy alcohol use (Hawkins et al., 1999). At age 21, students who had received the full intervention when young were also less likely to be involved in crime, to have sold illegal drugs in the past year, or to have received a court charge (Hawkins et al., 2005).

Steps to Respect is another multicomponent program that includes activities led by school counselors for youth involved in bullying, along with schoolwide prevention, parent activities and classroom management. (Frey et al., 2005, 2009; Baughman Sladky et al., 2015). One RCT of Steps to Respect showed a reduction of 31 percent in the likelihood of perpetrating physical bullying in intervention schools relative to control schools (adjusted odds ratio = 0.609) based on teacher reports of student behaviors (Brown et al., 2011). Brown and colleagues (2011) also showed significant improvements in student self-reports of positive school climate, increases in student and teacher/staff bullying prevention and intervention, and increases in positive bystander behavior for students in intervention schools compared to students in control schools (effect sizes ranged from 0.115 for student bullying intervention to 0.187 for student climate). They found no effects for student attitudes about bullying.

In a separate RCT of Steps to Respect, Frey and colleagues (2009) found, using teacher observations of student playground behaviors, statistically significant declines over 18 months in bullying (d = 2.11, p < .01), victimization (d = 1.24, p < .01) and destructive bystander behavior (d = 2.26, p < .01) for students in intervention schools compared to students in con-

trol schools. While student self-reports of victimization declined across 18 months, student self-reports of aggressive behavior did not change.

One of the most comprehensive, long-term school-based programs that has been developed to prevent chronic and severe conduct problems in high-risk children is Fast Track. Fast Track is based on the view that antisocial behavior stems from the interaction of influences across multiple contexts such as school, home, and the individual (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999). The main goals of the program are to increase communication and bonds between and among these three domains; to enhance children’s social, cognitive, and problem-solving skills; to improve peer relationships; and ultimately to decrease disruptive behavior at home and in school. Fast Track provides a continuum of developmentally sequenced preventive intervention spanning grades 1 through 10. It includes some of the program elements and frameworks mentioned above, such as a social-emotional learning curriculum developed in elementary school called Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies, as well as a version of the Coping Power program for higher-risk students. Other elements include support to parents, which is tailored to meet the unique needs of the family and youth.

Thus, Fast Track is a combination of multiple programs across the tiers. It has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing aggression and conduct problems, as well as reducing associations with deviant peers, for students of diverse demographic backgrounds, including sex, ethnicity, social class, and family composition differences (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2002, 2010; National Center for Health Statistics and National Center for Health Services Research, 2001). In an examination of the longitudinal outcomes of high-risk children who were randomly assigned by matched sets of schools to intervention and control conditions, the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (2011) showed that 10 years of exposure to Fast Track intervention prevented lifetime prevalence (assessed in grades 3, 6, 9, and 12) of psychiatric diagnoses for conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, externalizing disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

In addition, a recent RCT of Fast Track showed that early exposure to the intervention substantially reduced adult psychopathology at age 25 among high-risk early-starting conduct-problem children (Dodge et al., 2015). Specifically, intent-to-treat logistic regression analyses showed that 69 percent of participants in the control condition displayed at least one externalizing, internalizing, or substance use psychiatric problem (assessed via self-report or peer interview) at age 25, compared to 59 percent of those assigned to intervention (OR = 0.59, 95% CI [0.43, 0.81]; number needed to treat = 8). Intervention participants also received lower severity-weighted violent crime conviction scores (standardized estimate = −0.37). This study was a random assignment of nearly 10,000 kindergartners in three cohorts,

who were followed through a 10-year intervention and then assessed at age 25 via arrest records, condition-blinded psychiatrically interviewed participants, and interview of a peer knowledgeable about the participant.

The above descriptions of the selected universal multicomponent programs that address bullying or related behavior and their tiered levels of prevention are summarized in Table 5-1. The ecological contexts in which these programs operate are summarized in Table 5-2.

| Program | Origin | Program Type | Typical Delivery Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olweus Bullying Prevention Program | Norway | Bullying prevention, school, school climate, environmental strategies | School |

| Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) | School climate, academic engagement, behavioral support, interpersonal skills, school/classroom environment | School | |

| KiVa Antibullying Program | Finland | Classroom curricula, school/classroom environment, bullying prevention/intervention, children exposed to violence | School |

| Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum | U.S. | Social-emotional curricula, conflict resolution/interpersonal skills, school/classroom environment, bullying prevention/intervention | School |

Examples of School-Based Selective and Indicated Prevention Programs to Address Bullying or Related Behaviors

As noted above, many of the schoolwide and universal prevention models included elements across the tiers, but here the committee considers programs that are largely focused at the selective and indicated level. Within schools, it is common for students who are involved in bullying to

| Targeted Population | Age Range of Children Served | Program Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Children in kindergarten and elementary, middle, and high schools | 5-18 |

|

| Children in preschool, kindergarten, and elementary, middle, and high schools | 4-18 |

|

| All children | 5-14 |

|

| Children in preschool/kindergarten, elementary school, and middle school | 5-12 |

|

| Program | Origin | Program Type | Typical Delivery Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steps to Respect | U.S. | Bullying prevention, teacher training, social-emotional curricula, conflict resolution/interpersonal skills, school/classroom environment | School |

| Good Behavior Game | U.S. | Classroom management, classroom environment | School |

| Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers (LIFT) | U.S. | Academic engagement, classroom curricula, conflict resolution/interpersonal skills, parent training, school/classroom environment, children exposed to violence, alcohol and drug abuse prevention | School |

| Raising Healthy Children | U.S. | Academic engagement, conflict resolution/interpersonal skills, parent training, school/classroom environment, alcohol and drug abuse prevention | Home, School |

| Fast Track | U.S. | Academic engagement, social-emotional curricula, classroom curricula, conflict resolution/interpersonal skills, parent training, school/classroom environment | School |

SOURCE: Program information was obtained from Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development at http://www.blueprintsprograms.com/programs [June 2016] and CrimeSolutons.gov at http://www.crimesolutions.gov/ [June 2016].

| Targeted Population | Age Range of Children Served | Program Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Students in elementary and middle schools | 8-12 |

|

| Children in kindergarten, elementary school | 6-10 |

|

| Children in elementary school and their families | 6-11 |

|

| Children and their families | 7-16 |

|

| Children identified for disruptive behavior and poor peer relations. | 5-15 |

|

NOTE: The information provided in Table 5-1 is meant to illustrate core features of program elements and focus rather than provide a detailed assessment of all aspects of a program or its demonstrated effects. The table is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all prevention pograms.

| PROGRAM | ||||||

| Olweus Bullying Prevention Program | ||||||

| Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports | ||||||

| KiVa Antibullying Program | ||||||

| Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum | ||||||

| Steps to Respect | ||||||

| Good Behavior Game | ||||||

| Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers | ||||||

| Raising Healthy Children | ||||||

| Fast Track | ||||||

NOTE: The information provided in Table 5-2 is meant to illustrate core features of program elements and focus rather than provide a detailed assessment of all aspects of a program or its demonstrated effects. The table is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all prevention programs.

SOURCE: Program information was obtained from Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development at http://www.blueprintsprograms.com/programs and CrimeSolutons.gov at http://www.crimesolutions.gov/ [June 2016].

be referred for some type of school-based or community counseling services (Swearer et al., 2014).

McElearney and colleagues (2013) reported that school counseling was an effective intervention for middle school students who had been bullied when the counseling focused on improving peer relationships. In their study, they collected longitudinal data from 202 students (mean age = 12.5) using

the self-rated Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).4 In total, 27.2 percent of the student referrals to the intervention related to being bullied. Students who had been bullied had significantly higher initial status scores (LGC initial score = 1.40, p < .001) on the Peer Problems subscale of the SDQ and experienced a significantly more rapid rate of decrease on this subscale (LGC rate of change score = −0.25, p < .001) with each successive session of school counseling, compared with those students who had accessed the intervention for another reason. However, counseling sessions probably vary considerably in the services provided and the extent to which they employ evidence-based models.

A few studies have examined social workers or school mental health staff who provide intervention for youth involved in bullying, but the research in this area is rather weak, with relatively few systematic studies focused on assessing the impacts of selective and indicated programs on bullying (Swearer et al., 2014). Moreover, given the difficulty of determining the efficacy of counseling as an intervention per se, the committee focuses here more specifically on particular structured preventive intervention models that have been more formally articulated in a curriculum, many of which are delivered by school-based counselors, social workers, or psychologists.

For example, Berry and Hunt (2009) found preliminary support for a cognitive-behavioral intervention for anxious adolescent boys in grades 7-10 (mean age of 13.04 years) who had experienced bullying at school. Fung (2012) assessed a group treatment for youth ages 11-16, provided by social workers in Hong Kong using a social information processing model. Students were selected for intervention based on their high levels of aggressive behavior rather than bullying specifically, but the author did find that after 2 years of the intervention, students reported a decrease in reactive aggression but not proactive aggression. Fung (2012) also found that cognitive-behavioral group therapy was effective in reducing anxious and depressed emotions in children who are both the perperator and target of bullying.

One of the few evidence-based targeted intervention programs for late preadolescent children is the Coping Power Program (Lochman et al., 2013). Coping Power targets aggressive youth and their parents and is delivered by counselors in small groups over the course of a school year. Additional supports are provided to teachers to promote generalization of skills into nongroup settings. The program has demonstrated significant improvements in aggressive-disruptive behaviors and social interactions, many of which were maintained at 3-year follow-up for children from fourth through sixth grade (Lochman et al., 2013).

___________________

4 The SDQ is a brief behavioral screening questionnaire that asks about 25 attributes, some positive and others negative (Goodman, 1997).

Having available strategies to cope with stress has also been shown to reduce depression among older adolescents who were bullied (Hemphill et al., 2014). Although originally developed for students in grades 4-6, there is currently an ongoing 40-school randomized trial testing a middle school version of this model; the trial has a particular focus on assessing outcomes related to bullying (Bradshaw et al., in press); a high school model of Coping Power is also currently in development and will soon be tested on 600 urban high school students (Bradshaw et al., in press).

DeRosier (2004) and DeRosier and Marcus (2005) evaluated the effects of a social-skills group intervention for children experiencing peer dislike, bullying, or social anxiety. In their study of third graders randomly assigned to treatment or to no-treatment control, DeRosier and Marcus (2005) showed that aggressive children exposed to the program reported greater declines in aggression and bullying behavior and fewer antisocial affiliations than aggressive children in the no-intervention control condition. The intervention resulted in decreased aggression on peer reports (Cohen’s d = 0.26), decreased targets of bullying on self-reports (Cohen’s d = 0.10) and fewer antisocial affiliations on self-reports (Cohen’s d = 0.11) for the previously aggressive children (DeRosier and Marcus, 2005).

A study of elementary school students exposed to the FearNot! virtual learning intervention to enhance coping skills of children who were bullied showed a short-term improvement on escaping being bullied (Sapouna et al., 2010). In a separate evaluation of the FearNot! Program in the UK and German schools, exposure to the intervention was found to help non-involved primary grade children to become defenders of the target in virtual bullying situations, at least for youth in the German sample (Vannini et al., 2011).

There are also a number of preventive interventions that aim to address mental health problems but may also prove to be helpful for youth who are involved in bullying. For example, a school-based version of cognitive-behavioral therapy is Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS). This evidence-based treatment program is for youth ages 10-15 who have had substantial exposure to violence or other traumatic events and who have symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the clinical range. The CBITS Program has three main goals: (1) to reduce symptoms related to trauma, (2) to build resilience, and (3) to increase peer and parent support. Based on a model of trauma-informed care, CBITS was developed to reduce symptoms of distress and build skills to improve children’s abilities to handle stress and trauma in the future. The intervention incorporates cognitive-behavioral therapy skills in a small group format to address symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression related to exposure to violence. CBITS was found to be more accessible to families who may not have been able or willing to participate outside of schools. CBITS was also

found to significantly improve depressive symptoms in students with PTSD (Jaycox et al., 2010).

Examples of Family-Focused Preventive Interventions to Address Bullying

A few family-focused preventive interventions have been developed that may also demonstrate promising effects on bullying. For example, the Incredible Years Program aims to reduce aggressive and problem behaviors in children, largely through supports to parents, as well as students and teachers. It focuses on social skills training components (Webster-Stratton, 1999) and targets elementary school students with the aim of preventing further aggression and related behavior problems for youth with conduct problems but whose behavior would not yet be considered in the clinical range requiring treatment. Barrera and colleagues (2002) showed that high-risk elementary school children in the Incredible Years Program displayed lower levels of negative social behavior, including aggression, compared to control youth who did not receive the intervention. In another study, Webster-Stratton and colleagues (2008) showed that teacher training in combination with Dinosaur School in Head Start and first grade classrooms with at-risk students resulted in improved social competence and self-regulation and in fewer youth conduct problems. There is also a universal version of the Incredible Years Program delivered by teachers, which is currently being tested in two separate randomized trials. To the committee’s knowledge, bullying has not been assessed as an outcome in prior studies of Incredible Years, although several impacts on other discipline and behavior problems have been observed in prior RCTs.

Another family-focused program is The Family Check-Up (also known as the Adolescent Transitions Program). This multilevel, family-centered intervention targets children at risk for problem behaviors or substance use. The Family Check-Up had historically been delivered in middle school settings, but more recent studies have extended the model to younger populations (e.g., 2-5 year olds in Dishion et al., 2014). Parent-focused elements of The Family Check-Up concentrate on developing family management skills such as using rewards, monitoring, making rules, providing reasonable consequences for rule violations, problem solving, and active listening (Dishion and Kavanagh, 2003). Connell and colleagues (2007) found that The Family Check-Up resulted in significantly fewer arrests; less use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana; and less antisocial behavior for intervention youth, compared with control group youth.

Another targeted program that includes supports for families is the Triple P intervention. A RCT of Resilience Triple P for Australian youth 6 to 12 years old found significant improvements for intervention youth compared to controls on teacher reports of overt victimization (d = 0.56),

and child overt aggression toward peers (d = 0.51) as well as improvements in related mental health such as internalized feelings and depressive symptoms. The intervention that combined facilitative parenting with social and emotional skills training worked best (Healy and Sanders, 2014). An earlier study of Triple P for preschoolers at risk for conduct problems found that a version delivered by practitioners (clinical psychologists, psychologists, and psychiatrists) trained and supervised in the delivery of the interventions was more effective in reducing problem behaviors compared to a wait-list condition and a Triple P program that was self-directed (Sanders et al., 2000).

In addition to the largely school- and family-based programs summarized above, there are several evidence-based interventions that are more typically provided in the community (Baughman Sladky et al., 2015). Although these programs focus more generally on violence and aggression prevention, they may also produce effects on bullying related behaviors, such as conduct problems for perpetrators or those at risk for perpetration, or they may address the behavioral and mental health consequences of being bullied.

For example, a widely utilized intervention to address mental health issues for children and adolescents is Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) which has been shown to be effective in reducing mental health symptoms related to violence exposure (Cohen et al., 2006). TF-CBT has been particularly effective in treating children who are victims of sexual abuse (Cohen et al., 2005). While not specifically used to address being a target of bullying, TF-CBT can be used to treat complex trauma and has been shown to result in improvements to mental health issues related to peer victimization including PTSD symptoms, depression, anxiety, and externalizing behavior problems (Cohen et al., 2004; Deblinger et al., 2011).

Programs that are delivered in the community often include supports for parents as well as the youth. For example, Functional Family Therapy (FFT) is a family-based intervention program that targets youth between the ages of 11 and 18 who are at risk for and/or presenting with delinquency, violent or disruptive behavior, or substance use (Baughman Sladky et al., 2015). It is time-limited, averaging 8-12 sessions for referred youth and their families, with generally no more than 30 hours of direct service time for more difficult cases. FFT is multisystemic and multilevel in nature, addressing individual, family, and treatment system dynamics. It integrates behavioral (e.g., communication training) and cognitive-behavioral interventions (e.g., a relational focus). Assessment is an ongoing and multifaceted part of each phase (Henggeler and Sheidow, 2012). Evaluations of FFT have shown significant improvements in delinquent behavior and recidivism (Aos et al., 2011; Sexton and Alexander, 2000).

Brief Strategic Family Therapy (BSFT) is a short-term (approximately 12-15 sessions over 3 months) family-based intervention for children and youth ages 6-17 who are at risk for substance abuse and behavior prob-

lems (Robbins et al., 2002, 2007; Szapocznik and Williams, 2000). BSFT employs a structural family framework and focuses on improving family interactions. Evaluation results demonstrate decreases in substance abuse, conduct problems, associating with antisocial peers, and improvements in family functioning. In a small randomized trial of girls who were perpetrators of bullying, Nickel and colleagues (2006) found a decrease in bullying behavior (and expressive aggression) in the BSFT group, with improvements maintained at 1-year follow-up. Similar findings were observed in a separate study of BSFT for boys who were involved in bullying behavior. (Nickel et al., 2006).

Wraparound/Case Management is a multifaceted intervention designed to keep delinquent youth at home and out of institutions by “wrapping” a comprehensive array of individualized services and support networks “around” young people, rather than forcing them to enroll in predetermined, inflexible treatment programs (Bruns et al., 1995; Miles et al., 2006). Evaluations of Wraparound have found marked improvement in behavior and socialization, and youth in the intervention group were significantly less likely to reoffend compared to graduates of conventional programs (Carney and Buttell, 2003; Miles et al., 2006).

Multisystemic Therapy (MST) targets chronic, violent, or substance-abusing male or female juvenile offenders, ages 12-17, at risk of out-of-home placement, along with their families. MST is a family-based model that addresses multiple factors related to delinquency across key socioecological settings. It promotes behavior change in the youth’s natural environment, using a strengths-based approach (Henggeler, 2011). Critical service characteristics include low caseloads (5:1 family-to-clinician ratio), intensive and comprehensive services (2-15 hours per week) and time-limited treatment duration (4-6 months) (Henggeler et al., 1999). Treatment adherence and fidelity are key ingredients for achieving long-term, sustained effects and decreasing drug use. Evaluations of MST that examined delinquency rates for serious juvenile offenders demonstrated a reduction in long-term rates of re-arrest, reductions in out-of home placements, and improvements in family functioning, and decreased mental health problems for serious juvenile offenders (Greenwood and Welsh, 2012; Schaeffer and Borduin, 2005). A recent meta-analysis of the effectiveness of MST across 22 studies containing 322 effect sizes found small but statistically significant treatment effects for its primary outcome of delinquent behavior, but the meta-analysis also found secondary outcomes such as psychopathology, substance use, family factors, out-of-home placements, and peer factors. For example, considering MST as an intervention that may affect bullying related behaviors, eight studies assessing peer relations showed improvements for aggressive youth treated with MST compared to youth treated via other modalities (mean effect size d = 0.213) (van der Stouwe et al., 2014).

Another communitywide prevention model that holds promise for reducing violence and related behavior problems is the Communities That Care (CTC) framework. CTC is a system for planning and organizing community resources to address adolescent problematic behavior such as aggression or drug use. It has five phases to help communities work toward their goals. The CTC system includes training events and guides for community leaders and organizations. The main goal is to create a “community prevention board” comprising public officials and community leaders to identify and reduce risk factors while promoting protective factors by selecting and implementing tested interventions throughout the community. Based on communitywide data on risk and protective factors, schools may select from a menu of evidence-based programs, which includes some of

| Program | Origin | Program Type | Typical Delivery Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coping Power Program | U.S. | Cognitive behavioral treatment, parent training, social-emotional learning | School |

| Incredible Years | U.S. | Academic engagement, cognitive behavioral treatment, social-emotional curricula, conflict resolution/interpersonal skills, family therapy, group therapy, parent training, school/classroom environment | Home, school, community |

| The Family Check-Up (formerly Adolescent Transitions) | U.S. | Academic engagement, crisis intervention/response, family therapy, parent training, school/classroom environment, motivational interviewing | School |

| Triple P | Australia | Parent training | School, community, home, hospital/medical center, mental health/treatment center |

the models listed above. Thus, CTC is more of a data-informed process for selecting and implementing multiple evidence-based programs. As a result, it is difficult to attribute significant improvements in youth behavior to any one specific program. However, randomized studies testing the CTC model have shown statistically significant positive effects on delinquency, alcohol use, and cigarette use, all of which were lower by grade 10 among students in CTC communities, compared to students in control communities (Hawkins et al., 2011).

Descriptions of a subset of selective and indicated prevention programs that address bullying or related behavior and their tiered level of prevention are summarized in Table 5-3. The ecological contexts in which these programs operate are summarized in Table 5-4.

| Targeted Population | Age Range of Children Served | Program Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Aggressive youth and their parents | 8-15 |

|

| Children at high risk for problem behaviors or substance use, along with their parents and teachers | 2-8 |

|

| Families | 2-7 |

|

| Parents with a child in the age range between birth and 12 years | 0-12 |

|

| Program | Origin | Program Type | Typical Delivery Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) | Cognitive behavioral treatment, group therapy, individual therapy, school/classroom environment, trauma-informed | School, high crime neighborhood/hot spots | |

| Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) | Cognitive behavioral treatment, family therapy, parent training, trauma-informed | Inpatient/out-patient | |

| Functional Family Therapy (FFT) | U.S. | Family therapy, individual therapy, probation/parole services | Inpatient/outpatient, home, community |

| Brief Strategic Family Therapy (BSFT) | U.S. | Alcohol and drug therapy/treatment, conflict resolution/interpersonal skills, family therapy, parent training, alcohol and drug prevention | Home, workplace, community |

| Wraparound/Case Management | U.S. | Individualized case management via team planning that is family-driven, culturally competent, and community-based | Home, community |

| Multisystemic Therapy (MST) | U.S. | Alternatives to detention, cognitive behavioral treatment, conflict resolution/interpersonal skills, family therapy, individual therapy, parent training | Home, community, school |

| Communities That Care (CTC) | U.S. | Classroom curricula, school/classroom environment, community crime prevention, alcohol and drug prevention | School, community |

NOTE: The information provided in Table 5-3 is meant to illustrate core features of program elements and focus rather than provide a detailed assessment of all aspects of a program or its demonstrated effects. The table is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all prevention programs.

| Targeted Population | Age Range of Children Served | Program Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Children exposed to violence or other traumatic events |

|

|

| Children exposed to violence and their families | 3-14 |

|

| Young offenders and their families | 11-18 |

|

| Children at risk for substance abuse and behavior problems and their families | 6-17 |

|

| Children and their families | 6-18 |

|

| Young offenders and their families | 12-17 |

|

| Infant, early childhood-preschool, late childhood, kindergarten-elementary school, early adolescence, middle school, late adolescence, high school, early adulthood | 0-18 |

|

SOURCE: Program information was obtained from Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development at http://www.blueprintsprograms.com/programs and CrimeSolutons.gov at http://www.crimesolutions.gov/ [June 2016].

NOTE: The information provided in Table 5-4 is meant to illustrate core features of program elements and focus rather than provide a detailed assessment of all aspects of a program or its demonstrated effects. The table is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all prevention programs.

SOURCE: Program information was obtained from Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development at http://www.blueprintsprograms.com/programs [June 2016] and CrimeSolutons.gov at http://www.crimesolutions.gov/ [June 2016].

Examples of Preventive Intervention to Address Cyberbullying and Related Behaviors