4

Job and Health Outcomes of Sexual Harassment and How Women Respond to Sexual Harassment

Knowing that greater than 50 percent of women faculty and staff and 20–50 percent of women students encounter sexually harassing conduct in academia,1 the question now becomes how significant of a problem this is to those women; to others in the sexually harassing environments; to the disciplines of science, engineering, and medicine (SEM); and to society. Sexual harassment2 has been studied in a variety of industries, social and occupational classes, and racial/ethnic groups. Negative effects have been documented in virtually every context and every group that has been studied. That is, the impact of sexual harassment extends across lines of industry, occupation, race, and social class (for meta-analytic reviews of these effects, see Chan and colleagues [2008], Ilies and colleagues [2003], Sojo, Wood, and Genat [2016], and Willness, Steel, and Lee [2007]). This chapter explores in more detail this research record on outcomes of sexual harassment and provides a conceptual review of the research3 on outcomes that are associated4 with sexual harassment experiences.

___________________

1 See Chapter 3 for the research on these prevalence rates.

2 There are three types of sexual harassment: gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. See Chapter 2 for further descriptions.

3 Wherever possible, the report cites the most recent scientific studies of a topic. That said, the empirical research into sexual harassment, using rigorous scientific methods, dates back to the 1980s. This report cites conclusions from the earlier work when those results reveal historical trends or patterns over time. It also cites results from earlier studies when there is no theoretical reason to expect findings to have changed with the passage of time. For example, the inverse relationship between sexual harassment and job satisfaction is a robust one: the more an individual is harassed on the job, the less she or he likes that job. That basic finding has not changed over the course of 30 years, and there is no reason to expect that it will.

4 Much of the research in this area is based on correlational survey data, which cannot support definitive causal conclusions; there have, however, been some experiments that do point to causal

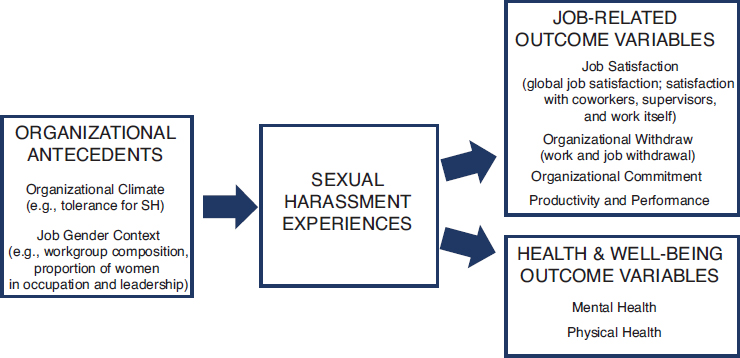

SOURCE: Adapted from Willness, Steel, and Lee 2007.

OUTCOMES OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT FOR INDIVIDUALS

Numerous robust studies have documented links between sexual harassment and declines in psychological and professional well-being. As a result, researchers have established a conceptual model of the factors that predict sexual harassment experiences (antecedents, examined in Chapter 3) and the outcomes associated with sexual harassment experiences (Figure 4-1). Overall, the research has demonstrated that women’s experiences of sexual harassment are associated with reductions in their professional, psychological, and physical health. The research also shows that the relationships between sexual harassment and these outcomes remain significant even when controlling for (1) the experiences of other stressors (e.g., general job stress, trauma outside of the work, etc.), (2) other features of the job (occupational level, organizational tenure, workload), (3) personality (negative affectivity, neuroticism, narcissism), and (4) other demographic factors (age, education level, race) (Cortina and Berdahl 2008). Some research also shows that sexual harassment has stronger relationships with women’s well-being than other job-related stressors, which emphasizes just how significant this issue is in educational and work settings (Fitzgerald et al. 1997). Other studies, moreover, show that negative effects extend to witnesses, workgroups, and entire organizations. The more often women are sexually harassed in a context, the more they think

___________________

connections between harassment and outcomes (e.g., Woodzicka and LaFrance 2005; Schneider, Tomaka, and Palacios 2001). Most of these correlational studies do not report the proportion of each sample who experiences each outcome; they instead focus on the strength of the relationship between sexual harassment and outcomes.

about leaving (and some do ultimately leave); the net result of sexual harassment is therefore a loss of talent, which can be costly to organizations and to science, engineering, and medicine.

Research has shown that even low-frequency incidents of sexual harassment can have negative consequences, and that these women’s experiences are statistically distinguishable from women who experienced no sexual harassment (Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997; Langhout et al. 2005). Not surprisingly, the research has also shown that as the frequency of sexual harassment experiences goes up, women experience significantly worse job-related and psychological outcomes (Fitzgerald et al. 1997; Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997; Magley, Hulin, et al. 1999; Leskinen, Cortina, and Kabat 2011). Relatedly, research has shown that gender harassment (a type of sexual harassment, which tends to occur at high frequencies) can have similar effects as unwanted sexual attention and sexual coercion (types of sexual harassment, which tend to be rare). In other words, gender harassment can be just as corrosive to work and well-being (Langhout et al. 2005; Leskinen, Cortina, and Kabat 2011; Sojo, Wood, and Genat 2016). This emphasizes the importance of not dismissing gender harassment as a “lesser,” inconsequential form of sexual harassment. It is also significant to note that the impacts women experience are in no way dependent on them labeling the experience as sexual harassment (Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997; Cortina and Berdahl 2008; Magley, Hulin, et al. 1999; Magley and Shupe 2005; Munson, Miner, and Hulin 2001).

Professional Outcomes

Extensive research shows that sexual harassment takes a toll on women’s professional well-being. This is true across a variety of industries, from academia to the military to the Fortune 500. Studies have considered a range of professional well-being outcomes, in particular, job satisfaction, organizational withdrawal, organizational commitment, job stress, and productivity or performance decline.

A host of studies have linked sexual harassment with decreases in job satisfaction. This finding applies to not only white women in the U.S. civilian workforce5 but also employees in the U.S. military and police force,6 women of color

___________________

5Bond et al. 2004; Cortina, Lonsway, et al. 2002; Fitzgerald, Drasgow, et al. 1997; Glomb et al. 1999; Harned and Fitzgerald 2002; Holland and Cortina 2013; Lim and Cortina 2005; Magley and Shupe 2005; Morrow, McElroy, and Phillips 1994; Munson, Hulin, and Drasgow 2000; Piotrkowski 1998; Ragins and Scandura 1995; Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997.

6 For example, Bergman and Drasgow 2003; Fitzgerald, Drasgow, and Magley 1999; Harned and Fitzgerald 2002; Harned et al. 2002; Langhout et al. 2005; Lonsway, Paynich, and Hall 2013; Magley, Waldo, et al. 1999.

in the United States,7 and nations outside of the United States.8 When the relationship between sexual harassment and job satisfaction is studied in more detail, data show that the dissatisfaction is notably worse when assessing interpersonal relations with supervisors and coworkers; however, there is less of a decrement in satisfaction with noninterpersonal job aspects such as the work, pay, or career progress (Willness, Steel, and Lee 2007).

Studies examining organizational withdrawal sometimes further categorize this professional outcome as (1) work withdrawal (distancing oneself from the work without actually quitting) and (2) job withdrawal (turnover thoughts, intentions, or actions). Work withdrawal is defined as “employees’ attempts to remove themselves from the immediate work situation while still maintaining organizational membership” (Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997). It includes absenteeism (i.e., more frequent time off), tardiness, and use of sick leave (measured on scales where respondents indicated desirability, frequency, likelihood, and ease of engaging in these behaviors) and unfavorable job behaviors (e.g., making excuses to get out of work, neglecting tasks not evaluated on performance appraisals) (Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997). Many studies have found that sexual harassment predicts work withdrawal (Barling, Rogers, and Kelloway 2001; Cortina et al. 2002; Fitzgerald et al. 1997; Culbertson and Rosenfeld 1994; Glomb et al. 1999; Holland and Cortina 2013; Lonsway, Paynich, and Hall 2013; Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997; USMSPB 1995; Wasti et al. 2000).

In a meta-analysis of studies, researchers found that while both work and job withdrawal are related to sexual harassment experiences, work withdrawal was found to be more significantly related to sexual harassment than job withdrawal—meaning targets are more likely to disengage from their work but not as likely to leave their job. These strategies can be viewed as ways to avoid further exposure to sexual harassment (Willness, Steel, and Lee 2007).

The second type of organizational withdrawal, job withdrawal, is “defined by employees’ intentions to leave their jobs and the organization itself and usually manifests through turnover or retirement” (Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997). It is measured by asking respondents “to indicate the likelihood of resigning in the next few months, the desirability of resigning, the frequency of thoughts about resigning, and the ease or difficulty of resigning on the basis of financial and family considerations and the probability of finding other employment” (Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997). Many studies have documented links between sexually harassing experiences and job withdrawal thoughts and intentions (Barling et al. 1996; Cortina, Lonsway, et al. 2002; Fitzgerald et al. 1997; Glomb et al. 1999; Lim and Cortina 2005; Holland and Cortina 2013; Lonsway, Paynich, and Hall 2013; Magley and Shupe 2005; O’Connell and Korabik 2000;

___________________

7 For example, Bergman and Drasgow 2003; Cortina, Fitzgerald, and Drasgow 2002; Shupe et al. 2002; Piotrkowski 1998.

8 Canada: Barling et al. 1996; O’Connell and Korabik 2000. Mainland China: Shaffer et al. 2000. Hong Kong: Chan, Tang, and Chan 1999; Shaffer et al. 2000. Turkey: Wasti et al. 2000.

Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997; Shaffer et al. 2000; Shupe et al. 2002; Wasti et al. 2000). Thoughts and intentions of leaving are critical to understanding how sexual harassment drives women out of an institution or field, because one of the best predictors of an action (such as leaving an institution or leaving the field) is thought and intention to commit that action. That being said, one study followed 11,521 military servicewomen over a 4-year time span, finding that sexual harassment led to actual turnover behavior over time; this effect held even after controlling for job satisfaction, organizational commitment, marital status, and rank (Sims, Drasgow, and Fitzgerald 2005).

Sexual harassment is also associated with reduced productivity and performance for the target (Barling, Rogers, and Kelloway 2001; Magley, Waldo, et al. 1999; USMSPB 1995; Woodzicka and LaFrance 2005). Some studies suggest that when organizational commitment declines, so do targets’ performance and work productivity. One unique experiment demonstrated that women’s verbal performance suffered as a result of subtle sexual harassment (Woodzicka and LaFrance 2005). Additional research has shown that it is not just targets’ performance but also workgroup or team productivity that is undercut by sexual harassment experiences. Workgroup productivity is often assessed based on “respondents’ perceptions of how well their workgroup performs quality work together” (Willness, Steel, and Lee 2007). One study demonstrated links between sexual harassment in teams and objective measures of those teams’ financial performance (Raver and Gelfand 2005).

Another key measure of sexual harassment outcomes in the workplace is the commitment of individuals to their organization. This measure reveals feelings of disillusionment and anger with an organization and beliefs that the organization is to blame for the experiences they had (Willness, Steel, and Lee 2007). Significantly, while this is an impact on the target of the harassment, this outcome can also negatively affect the organization, as the reduced commitment to the organization may result in employees leaving the organization or taking retaliatory actions against the organization. Research shows that as women experience more instances of sexual harassment, the less committed they feel toward their place of work (Barling, Rogers, and Kelloway 2001; Bergman and Drasgow 2003; Fitzgerald, Magley, et al. 1999; Harned and Fitzgerald 2002; Langhout et al. 2005; Magley, Waldo, et al. 1999; Magley and Shupe 2005; Morrow, McElroy, and Phillips 1994; Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997; Shaffer et al. 2000; Chan et al. 2008). In a meta-analysis of studies, Willness, Steel, and Lee (2007) found that the effect size of the relationship between sexual harassment experiences and organizational commitment9 was similar to the effect size for global

___________________

9 Assessed by a weighted mean correlation corrected for reliability, rc = –0.249.

job satisfaction,10 but lower than the effect size for satisfaction with supervisors11 or coworkers.12

Many studies include job stress as a covariate in their harassment-outcome models, but when researchers have instead conceptualized job stress as an outcome, they have virtually always found that general job-related stress increases as sexual harassment becomes more frequent (Cortina, Lonsway, et al. 2002; Lim and Cortina 2005; Lonsway, Paynich, and Hall 2013; Magley and Shupe 2005; Morrow, McElroy, and Phillips 1994; O’Connell and Korabik 2000).

Other job-related outcomes beyond those covered by the above categories include: impaired team relationships and increased team conflict (Raver and Gelfand 2005); lower justice perceptions; greater distractibility (Barling, Rogers, and Kelloway 2001); and targets feeling the need to over-perform to gain acceptance and recognition in the workplace (Parker and Griffin 2002). For reviews of research on professional outcomes of sexual harassment, see Cortina and Berdahl (2008), Holland and Cortina (2016), and Fitzgerald and Cortina (2017).

Educational Outcomes

The impact that sexual harassment has on students at all levels of the educational continuum, from high school to graduate studies, is markedly similar to the impacts it has in the workplace. The following sections discuss educational consequences at the high school, undergraduate, and graduate school levels.

Research on students in high school who have experienced harassment shows that they report lowered motivation to attend classes, exhibit greater truancy, pay less attention in class, receive lower grades on assignments and in their overall grade point average, and seriously consider changing schools (Duffy, Wareham, Walsh 2004; Lee et al. 1996). Even young women who have not been harassed avoid taking classes from teachers with reputations for engaging in harassing behavior (Fitzgerald et al. 1988).

At the undergraduate level, sexual harassment (of which the most common type is gender harassment) has significant consequences on the educational path of students. The more often women students are harassed, the lower their assessments of the campus climate and likelihood of returning to the college or university if they had to make the decision again (Cortina et al. 1998). Even worse, sexually harassed students have reported dropping classes, changing advisors, changing majors, and even dropping out of school altogether just to avoid hostile environments (Huerta et al. 2006; Fitzgerald 1990).

The women who remain in school tend to suffer academically (Huerta et al. 2006; Reilly, Lott, and Gallogly 1986). If women feel that the academic environment is hostile toward them, they may not participate in informal activities that

___________________

10 rc = –0.245.

11 rc = –0.285.

12 rc = –0.316.

could enhance their experiences and result in academic advancement (Dansky and Kilpatrick 1997). Sexual harassment also may have an impact on a student’s self-esteem (Barickman, Paludi, and Rabinowitz 1992). Therefore, low levels of academic engagement, performance, and motivation provide explanations as to why sexual harassment is related to poor grades among female college students (Cammaert 1985; Huerta et al. 2006).

Using the Administrator Researcher Campus Climate Collaborative (ARC3) survey, Rosenthal, Smidt, and Freyd (2016) found that consistent with studies on other populations of targets, sexual harassment experiences by graduate students were associated with posttraumatic symptoms for both men and women. Female graduate students who indicated that they had experienced sexual harassment also reported a diminished sense of safety on campus. The University of Texas analysis of the ARC3 data suggests that across academic disciplines women who experienced sexual harassment from faculty/staff reported significantly worse physical and mental health outcomes than those who had not experienced sexual harassment.

Health and Well-Being Outcomes

Researchers measure health and well-being based on standard psychology research scales that include multiple questions (e.g., about symptoms of anxiety and depression) appropriate for a general (nonpsychiatric, nonhospitalized) population. Many studies of this topic have appeared in the clinical and psychiatric literatures, and their findings are striking.

The more often women experience sexual harassment, the more they report symptoms of depression, stress and anxiety, and generally impaired psychological well-being (Bergman and Drasgow 2003; Bond et al. 2004; Cortina, Fitzgerald, and Drasgow 2002; Culbertson and Rosenfeld 1994; Fitzgerald, Swan, and Magley 1997; Fitzgerald, Drasgow, and Magley 1999; Glomb et al. 1999; Harned and Fitzgerald 2002; Langhout et al. 2005; Lim and Cortina 2005; Magley, Hulin, et al. 1999; Magley, Cortina, and Kath 2005; Parker and Griffin 2002; O’Connell and Korabik 2000; Piotrkowski 1998; Richman et al. 1999, 2002; Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997; Schneider, Tomaka, and Palacios 2001; Vogt et al. 2005; Wasti et al. 2000). These results extend to women of color (e.g., Bergman and Drasgow 2003; Cortina, Fitzgerald, and Drasgow, 2002) as well as to gay men, lesbians, and transgender individuals (Irwin 2002). Other psychological outcomes of sexual harassment include the following:

- negative mood (Barling et al. 1996; Barling, Rogers, and Kelloway 2001; O’Connell and Korabik 2000);

- fear (Barling, Rogers, and Kelloway 2001; Culbertson and Rosenfeld 1994);

- disordered eating (Harned and Fitzgerald 2002; Huerta et al. 2006);

- self-blame, lowered self-esteem (Culbertson and Rosenfeld 1994; Harned and Fitzgerald 2002);

- increased use of prescription drugs (Richman et al. 1999) and alcohol (Rospenda et al. 2008; McGinley et al. 2011);

- anger, disgust (Culbertson and Rosenfeld 1994); and

- lowered satisfaction with life in general (Cortina, Fitzgerald, and Drasgow 2002; Fitzgerald, Swan, and Magley 1997; Glomb et al. 1999; Lim and Cortina 2005; Munson, Hulin, and Drasgow 2000; Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997; Wasti et al. 2000).

In a series of articles based on a longitudinal study of university employees, Richman and other social scientists documented associations between earlier sexual harassment and later alcohol use and misuse (Freels, Richman, and Rospenda 2005; Richman et al. 1999, 2002; Wislar et al. 2002).

Beyond showing significant associations between sexual harassment and psychological distress symptoms, some studies have investigated whether and when those symptoms meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis. If the sexual harassment is severe enough in either intensity (e.g., assault) and/or frequency and duration (multiple and repeated incidents over a significant length of time), targets are more likely to experience symptoms that rise to the level of a psychiatric disorder, including mood and anxiety disorders (Rosenthal, Smidt, and Freyd 2016; Ho et al. 2012; Fitzgerald, Buchanan, et al. 1999). For example, one study, based on a large national random sample of women, found that 1 in 5 self-identified sexual harassment targets reported symptoms fitting a DSM-IV diagnosis of Major Depression, and 1 in 10 had symptoms meeting criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (Dansky and Kilpatrick 1997).

Clinical evaluation has demonstrated that women who experience sexual harassment incur often inevitable and multiple losses, which contributes to psychological stress and distress and which cannot be captured by a diagnostic label. Specific types of losses vary depending on the circumstances of each situation and are often exacerbated after formal reporting. The tangible losses women experience can include the loss of a job and its associated economic, personal, and social benefits. Of these, loss of income and economic security is often the most stressful (Unger and Crawford 1996). Women experiencing sexual harassment also incur intangible but significant losses. They often lose self-esteem and confidence in themselves and their competency, and they often report loss of motivation or passion for their work. In addition, disruptions and loss of significant relationships, inside and outside the workplace or academic community, are common. These can include loss of important mentoring or coworker relationships and strain on family and social relationships, including relationships with intimate partners and social networks. Social support inside and/or outside the workplace is one of the most significant factors that can mitigate the stress and distress sexual harassment causes. The disruption and loss of these relationships

can deprive women of this support and can worsen the psychological and physical outcomes (Gold 2004).

When harassment results in stigmatization and the loss of a highly valued training opportunity or career, the effects on the target can be devastating, beyond the financial stresses associated with job loss. When a woman has made a personal, professional, and financial commitment to and investment in highly specialized science, engineering, and medical training, such as choosing to forego having children or investing years in “paying dues” to advance in her field, the loss of a training or employment position creates profound grief. For some women who value a science, engineering, and medical career in relatively small and highly specialized training institutions and occupations, as are often found in science, engineering, and medical fields, getting labeled as a complainer and someone who “causes trouble” can effectively end a woman’s career. Even if she is able to leave the environment in which the harassment has occurred, a “reputation” may prevent the woman from being accepted into the handful of similar training programs or obtaining the few available positions in science, engineering, and medicine (Gold 2004).

Compared with the research on psychological health outcomes, the literature on physical health outcomes is less extensive and appears to be indirect (i.e., emerging as a result of its link to psychological health (Cortina and Berdahl 2008; Gold 2004). In other words, women who are experiencing psychological distress may report stress-related physical complaints as well. Some research has documented links to overall health perceptions or satisfaction (Bergman and Drasgow 2003; Fitzgerald, Swan, and Magley 1997, Fitzgerald, Drasgow, and Magley 1999; Harned and Fitzgerald 2002; Harned et al. 2002; Lim and Cortina 2005; Magley, Hulin, et al. 1999; Wasti et al. 2000). Others have identified specific somatic complaints associated with harassing experiences; these include headaches, exhaustion, sleep problems, gastric problems, nausea, respiratory complaints, musculoskeletal pain, and weight loss/gain (Barling et al. 1996; Culbertson and Rosenfeld 1994; de Haas, Timmerman, and Höing 2009; Fitzgerald, Swan, and Magley 1997; Piotrkowski 1998; Wasti et al. 2000).

Specifically, one experiment has demonstrated a causal connection between gender harassment, the most common form of sexual harassment, and physiological measures of stress. When women were exposed to sexist comments from a male coworker, they experienced cardiac and vascular activity similar to that displayed in threat situations.13 This kind of cardiovascular reactivity has been linked to coronary heart disease and depressed immune functioning. The researchers conclude that if women are exposed to repeated, long-term gender harassment and the resulting physical stress, they could be at risk for serious long-term health problems (Schneider, Tomaka, and Palacios 2001).

___________________

13 The researchers measured cardiac and vascular activity using electrocardiography (EKG), impedance cardiography (ZKG), and an automated blood-pressure device.

Studies have shown that sexual harassment experienced by students is associated with negative health outcomes. According to the ARC3, data comparing the relationship between experiencing sexual harassment and negative physical and mental health outcomes across academic disciplines (i.e., non-SEM), female students who were sexually harassed had similar negative effects regardless of their disciplinary area. However, only female medical students who experienced sexual harassment by faculty or staff showed a negative impact on safety concerns; they reported feeling less safe on campus. Students who experienced sexual harassment by another student had similar responses as those who had been harassed by faculty or staff. Female medical school and engineering students both reported negative physical and mental outcomes, with female medical students also reporting feeling less safe on campus (see Swartwout 2018, Appendix D consultant paper in this report).

Outcomes and Harasser Power

While all types of sexual harassment will have negative effects, top-down sexual harassment (i.e., committed by a superior) is sometimes more harmful than peer harassment. For instance, studies have shown that working women who experience sexual harassment from higher-level men, rather than equal or lower-level men, experience greater impacts and negative consequences for targets’ job satisfaction, intent to leave one’s job, and organizational commitment, as well as health-related variables such as depression, emotional exhaustion, and physical well-being (Morrow, McElroy, and Phillips 1994; O’Connell and Korabik 2002). Moreover, research has reported that the more powerful the perpetrator, the more that women find his harassing conduct distressing (Cortina et al. 2002; Langhout et al. 2005). Huerta and colleagues’ (2006) study of college students found that academic satisfaction was lower when the harassment came from higher-status individuals (i.e., faculty, staff, or administrators). Theoretical explanations for the greater consequences associated with top-down sexual harassment include the target’s learned helplessness (Thacker and Ferris 1991), fear of the perpetrator’s ability to coerce sexual cooperation, and fear of job-related repercussions for failing to cooperate (Bergman et al. 2002; Cortina et al. 2002; Langhout et al. 2005; O’Connell and Korabik 2000).

It is important to recognize, however, that sexual harassment more often comes from same-status peers rather than higher-status authority figures (in part because employees and students typically interact with peers more often than superiors, and in many contexts peers far outnumber those in power). Moreover, research has documented many negative effects of peer-perpetrated harassment (Morrow, McElroy, and Phillips 1994; O’Connell and Korabik 2000), and some effects are just as bad regardless of the status of the perpetrator (Huerta et al. 2006; Morrow, McElroy, and Phillips 1994). For instance, Huerta and colleagues (2006) found that sexual harassment related to student symptoms of anxiety and

depression, irrespective of whether the harassment came from peers (i.e., fellow students) or from those in authority (administrators, staff, or faculty).

Outcomes for Underrepresented Groups

While it continues to be sparse, research examining the intersection of sexual harassment and race has been able to illuminate “unique, culture-specific factors” that affect the impacts of sexual harassment on women of color. A study by Cortina and colleagues (2002) on Latina populations showed that a set of sociocultural determinants specific to a population affect sexual harassment experiences. One of the main findings of this study supports the idea that sexual harassment experiences are more distressing for women of color when occurring simultaneously with other types of harassment in the workplace. That is, racial harassment in the workplace was the strongest factor associated with severe experiences of sexual harassment. This finding supports the idea that sexual harassment is perceived by the targets to be more severe in work and education environments that tolerate sexual, racial, and sexual-racial harassment (Cortina et al. 2002).

In addition to racial harassment, perpetrator power was also revealed to be a strong correlate with the severity of the sexual harassment experience. The study also found significant relations between the severity of the sexual harassment experience and Latina job satisfaction and mental health. The more severe the sexual harassment, the lower the satisfaction with work (which in turn relates to job withdrawal) as well as increased mental health issues (depressive, anxious, and somatic symptoms). This finding is consistent with studies on the impact of sexual harassment experiences of women in general (see above). A similar study conducted by Woods, Buchanan, and Settles (2009) examined the sexual harassment experiences of black women. The study looks specifically at cross-racial and intraracial sexual harassment experiences and how the two are appraised differently by black women. This study found evidence that perpetrator race plays a powerful predictor of sexual harassment appraisal. Black women in this study appraised cross-racial harassment to be more severe (i.e., more offensive, frightening, and disturbing) than intraracial harassment. These appraisals, moreover, were associated with more severe symptoms of posttraumatic stress (Woods, Buchanan, and Settles 2009). These studies, as do many others, demonstrate the nuanced dimensions by which women of color experience sexual harassment. Further research in this space would help to further illuminate the complicated dimensions of sexual harassment experiences.

Sexual- and gender-minority individuals, an often overlooked group, can also experience the impacts of sexual harassment differently. A study by Irwin (2002) reveals that the impact on health and well-being to gender minorities is alarming, with 90 percent of those in the sample indicating that they experienced increased anxiety and stress levels while on the job. Eighty percent of the respondents

suffered from depression, 63 percent experienced a loss of confidence and self-esteem, and 59 percent expressed that their personal relationships suffered due to ongoing workplace harassment. Additionally, several studies do point to adverse effects of a generally hostile environment for this population, ranging from coming-out stress to using the wrong pronouns, to accessibility to safe bathrooms, which suggests it is important to study sexual harassment in this population to see how it may intersect with other forms of harassment (such as heterosexist harassment and transgender harassment) and incivility (DuBois et al. 2017).

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that the multiple layers of an individual’s identity may affect the way one perceives and deals with sexual harassment in the workplace or academia.

OUTCOMES OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT FOR WITNESSES AND WORKGROUPS

Sexual harassment does not only impact the target but may also impact employees and coworkers who witness or hear about the experience. Several studies have attempted to document these impacts to show that negative impacts associated with indirect experiences of sexual harassment will also affect other women (and men) in the target’s workgroup or team (Glomb et al. 1997; Miner-Rubino and Cortina 2004, 2007; Hitlan, Schneider, and Walsh 2006).

In a study of female employees from a public utility company, Glomb and colleagues propose that ambient sexual harassment, defined as the indirect exposure to sexual harassment or “the general or ambient level of sexual harassment in a work group as measured by the frequency of sexually harassing behaviors experience by others in a woman’s work group” (1997, 309), will lead to similar negative outcomes as direct exposure. Glomb and colleagues point to research on organizational stressors such as racial harassment and organizational politics that are known to cause heightened stress to employees who are not themselves targets. In this study, they propose that such research suggests that “effects of job stressors are quite diffuse and extend beyond the focal target” (312). In extending this research to sexual harassment, Glomb and colleagues find that ambient sexual harassment in the workplace has a detrimental influence on an employee’s job satisfaction and psychological conditions. According to their findings, women who experience sexual harassment directly and indirectly report higher levels of absenteeism and intentions to quit, and are more likely to leave work early, take long breaks, and miss meetings (job withdrawal).

Similar conclusions have been made from other studies. For example, a study by Miner-Rubino and Cortina (2004) found that all employees in the workplace—both female and male—can suffer from working in a climate perceived to be hostile toward women. Consequently, the concept of ambient sexual harassment has significant implications for organizations. The studies above confirm that sexual harassment is not only an individual problem but also an organizational problem.

COPING WITH SEXUAL HARASSMENT: WHY WOMEN ARE NOT LIKELY TO REPORT

Only a very small literature examines how women respond to their experiences of sexual harassment, but it reveals that women do not respond the way many expect them to. As Fitzgerald, Swan, and Fischer (1995, 118) note, “legal proceedings . . ., in practice if not theory, hold the victim responsible for responding ‘appropriately,’ . . . placing the burden of nonconsent on the victim.” They go on to highlight that, up to that point in time, frameworks for understanding women’s responses to sexual harassment were typically grounded in an assumption that responses were typically viewed as simply more or less assertive (e.g., Gruber 1998). As Magley (2002) noted, “Unfortunately, one consequence of framing women’s responses, purely as a continuum of assertiveness is that responses other than assertiveness can be interpreted as weakness on the part of the recipient or as evidence that she did not handle it properly.” As we demonstrate in our review below, women’s actual responses are much more complex than simply asserting/reporting or not.

As Magley (2002) found, based on data from more than 15,000 women, “frequently, a woman’s responses, often aimed at ignoring or appeasing the harasser, are nonconfrontive and intent on maintaining a satisfactory relationship with the individual” (see also Wasti and Cortina [2003]). For example, nearly three-quarters (74.3 percent) of the women in one of seven of the datasets analyzed by Magley avoided their perpetrator, 72.8 percent detached themselves psychologically from the situation, 69.9 percent endured the situation without any attempt to resolve the situation, and 29.5 percent attempted to appease their perpetrator by making up an excuse to explain his behavior.

Seeking social support is also a typical response to sexual harassment. As summarized by Cortina and Berdahl (2008), approximately one-third of targets discuss their experience with family members and approximately 50–70 percent seek support from friends. In an effort to better understand the sexual harassment experiences of women in SEM fields, an area of research that has been scarcely explored, the National Academies Committee on the Impacts of Sexual Harassment in Academia commissioned the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) to conduct a series of interviews. The results from the interviews showed that women had numerous ways of coping with sexual harassment. For example, internal coping mechanisms included minimizing or normalizing the incidents (e.g., trying to ignore or laugh it off, not taking it personally); strategizing about how to be better prepared to respond to future incidents (or to redirect the person); engaging in mindfulness, spiritual, and self-healing activities; engaging in exercise or physical activity; trying to get tougher; and staying focused on their careers (RTI 2018). Women also reached out to friends and family, which was considered almost universally to be a positive choice. But reactions from colleagues turned out to be a mixed bag for these women. Here is what one woman heard from a colleague:

I would tell [friends] outside this profession who would be like, “Are you kidding me, what?” But the people who work for this institution were like, “Can’t you just suck it up? This is not going to go well for you if you report. You don’t want to make a fuss.” I knew they were right, but at the same time, I really was like, “This is just too much. I shouldn’t have to be preparing to get raped when I go into work.” (Nontenure-track faculty member in medicine)

Other women found the advice from their colleagues to be extremely helpful. They reported that female colleagues in particular were empathetic and bolstered the overall quality of their work life. One woman explained the level of support as follows:

I happen to be in a department that is well above the national average for women faculty in [predominantly male field]. Because of that, we have a really strong network of women who—I mean, we go out to coffee once a month just to talk about being female faculty from the full professor level all the way down to first-year assistant professors or instructors. Because of that, it’s easier to face some of these issues when you kind of have a team behind you. I know I’m lucky in having that kind of network here; most women faculty don’t. (Assistant professor of engineering)

In fact, some women said that without this support, they may have left their fields altogether. For those who did not have the support on campus, they sought it out at scientific conferences or professional forums. Finally, a few women turned to therapists to deal with their feelings following a sexual harassment incident. While only a small number took this route, those who did said that counseling was beneficial (RTI 2018).

When seeking support from those other than peers, only around one-third of women will reach out to those in their organization. Cortina and Berdahl (2008) found that only approximately one-third ever informally discuss their sexual harassment experience with their supervisors, which mirrors the 36.2 percent found by Magley (2002).

For making formal reports with an organization, the rates are even lower. Cortina and Berdahl (2008) found that only 25 percent of targets will file a formal report with their employer, and even a smaller fraction of them will take their claims to court. A report by the Association of American University Women (2005) reveals that almost half (49 percent) confide in a friend, 35 percent of undergraduate students tell no one, and only 7 percent report the incident to a college employee. Results from the 2016 ARC3 survey at the University of Texas System confirms that students have very low reporting rates, with only 2.2 percent of all students who experienced sexual harassment reporting it to the institution and 3.2 percent disclosing the experience to someone in a position of authority at the institution. In a study on graduate students, 6.4 percent of those who had been sexually harassed reported the incident (Rosenthal, Smidt, and Freyd 2016). For university faculty and staff, earlier research suggests the rates

are similar to that for graduate students, with 6 percent reporting their experience (Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997). Low reporting rates have been documented among all women, but women of color—black women, Asian American women, and Latinas—have been shown to report even less frequently than white women (e.g., Wasti and Cortina 2002).

As a coping mechanism, formal reporting for targets is the last resort: it becomes an option only when all others have been exhausted. Cortina and Berdahl (2008) explain that the reluctance to use formal reporting mechanisms is rooted in the “fear of blame, disbelief, inaction, retaliation, humiliation, ostracism, and damage to one’s career and reputation.” These fears are justified because reporting processes often bring few benefits and many costs to the targets. Studies show that women and nonwhites often resist naming something “discrimination” because it promotes their victimhood and loss of control (Bumiller 1987; Crosby 1993; Dodd et al. 2001; Stangor, Sechrist, and Jost 2001). Social psychologists have documented negative reactions such as contempt and laughter against women and African Americans who claim to have experienced discrimination (even when the subjects view evidence showing that discrimination probably occurred) (Kaiser and Miller 2003; Czopp and Monteith 2003). In a survey of 6,417 men and women in the military, the research demonstrated that not only could reporting sexual harassment trigger retaliation (despite this being illegal, see the discussion in Chapter 5), but also it was linked to lower job satisfaction and psychological distress (Bergman et al. 2002). Further, retaliation becomes more likely and severe when there is a power differential between the target and the harasser, as is often the case (Knapp et al. 1997). In another study, which surveyed 1,167 federal employees, the results show that employees with lower rank or hierarchical status in an organization experience higher rates of retaliation for reporting harassment (Cortina and Magley 2003).

Women who experience sexually harassing behaviors may also be unlikely to report because they believe or know that grievance procedures favor the institution over the individual. Research has shown that the more frequent the mistreatment is, the more that targets encounter retaliation—both professional and social—for speaking out (Cortina and Magley 2003). If targets fear reprisals, and feel that the institutional process will not serve them, they will be unlikely to report. In particular, students are often reluctant to start the formal grievance process with their campus Title IX officer because of fear of reprisal, expectation of a bad outcome, not knowing how to proceed, and concerns confidentiality cannot be guaranteed (Pappas 2016a; Harrison 2007).

In the qualitative study by RTI, female faculty responded similarly to questions about disclosure of sexual harassment: they would often feel that they had limited options for ways to address the issue without adversely affecting their careers. Furthermore, stark power differentials between the target and perpetrator exacerbated the sense of limited options. The researchers also noted that targets were often new faculty members, residents, and postdoctoral students, whereas

their perpetrators were often high-ranking faculty, professional mentors, or widely recognized experts. Perceived threats to tenure prospects; ability to freely pursue research and scientific stature opportunities; and threats to physical, emotional, and mental health were significant factors for women who have been sexually harassed in weighing whether or how to disclose the incident (RTI 2018).

The RTI research also reveals what women’s experiences were like when they did disclose or report an incident and shows that women who shared their experiences with their supervisors, deans, or chairs rarely experienced positive outcomes. A few expressed profound gratitude for having managers who believed them about their experiences and supported them in pursuing university-level reporting. More often, however, managers expressed mild sympathy but neither took any action nor encouraged the target to do so. Even more commonly, however, these proximal authority figures minimized or normalized the experience, discouraged further reporting, or recommended that the target “work it out” with her harasser (or some combination thereof). A woman who was harassed by her chair recounted the following:

I thought I’d talk to the ombudsman person, but then I talked to the dean and he insisted that he has talked to the vice president of the university and she had said that it’s just a bad start. You should have a three-way meeting with some external person where you come and talk and we’ll try to help you resolve the differences. I was too scared to do that because he was already trying to put subtle pressure on me, the chair I mean, by assigning me another course and all those kind of things. (Assistant professor of engineering)

Still others experienced direct retaliation from those to whom they reported harassment. For instance:

I reported to my program director, the chief resident, who I had already talked to about it, but this was more formal, and then the site director, because this was offsite . . . my program director pretty much left it up to the site director, who told me that I sounded just like his ex-wife, who we all know he hates, and that maybe if I stopped whining so much I would have more friends. So, they basically blew off the report then. And then he—the one I reported it to—started giving me failing grades. Like, we don’t really get grades as residents but we have competencies, and where he had given me good grades previously, directly after me telling him about what was happening, then his reporting of my grades just all went downhill from there. (Nontenure-track faculty member in medicine)

For the reasons described in this section, institutions should not expect to gain a comprehensive understanding of the extent of sexual harassment on their campus from the number of sexual harassment cases reported by targets. Rather, institutions should work to gain a better sense for the prevalence and impact of sexual harassment through regular, anonymous campus climate surveys, as described in Chapter 2.

OUTCOMES OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT IN ACADEMIC SCIENCE, ENGINEERING, AND MEDICINE

As has already been described in this report, women in academia have very different experiences of the science, engineering, and medical workplaces than men have. An atmosphere of gender discrimination pervades classrooms, laboratories, academic medical centers, field sites, observatories, and conferences, and women report that this climate contributes to the frequency of and experience with sexual harassment (RTI 2018, section 3-1). In addition to the organizational antecedents that characterize high-risk sexual harassment workplaces that tend to be found in science, engineering, and medicine—male domination and organizational tolerance—there are a few aspects of the job pipeline in these fields that make sexual harassment especially damaging to women’s careers.

To illustrate how sexual harassment impacts the careers of women in science, engineering, and medicine in higher education, our committee commissioned RTI International to conduct a series of interviews with female faculty who experienced sexually harassing behaviors. When these women were asked about how they felt their experiences with sexual harassment affected their career progressions, the predominant answers from respondents was one of negative trajectories. Several respondents indicated that they were forced to make major transitions in their career as a result of these experiences. Three themes emerged from this discussion regarding the impacts on their job opportunities, advancement, and tenure: stepping down from leadership opportunities to avoid the perpetrator, leaving their institution, and leaving their field altogether.

Stepping down from leadership opportunities to avoid the perpetrator. One woman whose experience was reported to human resources was instructed to resign from an important committee position to avoid interaction with the perpetrator, who was the chair of the committee. Another dropped out of a major research project that was part of an early-career mentoring organization because her mentor raped her. In both situations, others perceived the women negatively because colleagues did not know the reason for their decision; they saw this as particularly harmful because both women were at early stages in their careers.

So, there’s been a negative kind of chain of events where supervisors at the institution have seen that I dropped out of the research project and may not understand, because they were never told what happened. So, it seems . . . I have had a black, I have been blacklisted in some ways and not invited to join other research projects and perhaps seen as a failure. (Nontenure-track faculty member in geosciences)

A third woman stepped down from an assistant dean position that she was very passionate about to avoid having to interact with the dean, who had harassed her.

Leaving their institutions. Several women ended up leaving their institutions either because the climate was negative toward women or to avoid a specific perpetrator there who continued to harass them. Others were actively looking for opportunities that would enable them to leave for a better environment, but some questioned whether the environment would be any better at other institutions or not.

That is why I made this decision of leaving that university, even though I liked the department, I liked the students, I liked the place. I had to leave it, just because I didn’t want this bitterness to continue and affect me personally or professionally. (Assistant professor of engineering)

Leaving their fields altogether. One woman felt that she was forced out of her field because of retaliation for reporting sexual harassment, and another left her field to avoid interacting with the perpetrator.

These responses to sexual harassment, which are consistent with the most common coping mechanisms explained earlier in the chapter, are very problematic to science, engineering, and medicine, because they deprive the enterprise of a pool of talented women and limit their ability to advance and contribute to the work in these fields.

Specific analyses of the ARC3 data from the University of Texas System suggest there are some differences between academic disciplines in the outcomes from experiencing sexually harassing behavior. Women students in medical school, in the sciences, and in non-SEM fields who were harassed by faculty/staff reported feeling less safe on campus than those who had not experienced sexual harassment. Women engineering students were the only exception and did not report feeling less safe than those who had not been sexually harassed. Female science majors and non-SEM majors who experienced any sexual harassment by faculty or staff reported similar academic disengagement outcomes—reporting missing class, being late for class, making excuses to get out of class, and doing poor work—significantly more often than those who did not experience sexual harassment, while female engineering majors who experienced any sexual harassment by faculty or staff were only significantly more likely to report missing more classes and making more excuses to get out of classes than their peers who had not experienced harassment. And female medical students who experienced any sexual harassment by faculty or staff were only significantly more likely to report doing poor work than their peers who had not experienced sexual harassment.

Outcomes Connected with the Research Environments for Science, Engineering, and Medicine

Across the fields in academic science, engineering, and medicine, there is high value placed not only on your Ph.D. or M.D. institution but also on the lab, program, or hospital you come out of. The “pedigree” of your institutional af-

filiation and advisor strongly influence your chances of obtaining a tenure-track faculty position, particularly at an R1 institution. Within this context, specific aspects of the science, engineering, and medicine academic workplace tend to silence targets as well as limit career opportunities for both targets and bystanders.

Informal communication networks known as “whisper networks,”14 in which rumors and accusations are spread within and across specialized programs and fields, are common across many male-dominated work and education environments, including science, engineering, and medicine. Informal communication networks created by and for women are used to warn women away from particular programs, labs, or advisors. This has the effect of automatically reducing their options and chances for career success. Yet this protective type of networking is common and described by many women who experience sexually harassing behaviors and environments. For example:

It’s more calling them to discuss the tribal experience and just hear the yeah, I’ve dealt with it too, and it sucks and no, I don’t have any ideas for how to fix it, but this isn’t only happening to you, which is kind of the bonding moment. (Assistant professor of engineering)

These informal communication networks may be used to protect women from harassment, but they also limit opportunities (Sepler 2017; RTI 2018). When a female graduate student or postdoc finds herself experiencing sexual harassment, she has few choices to remove herself from the perpetrator or perpetrators aside from leaving that program or lab. This puts her at a significant disadvantage: if she leaves that program or lab, she may have no other options at that institution to conduct similar work. Consequently, her options are to start a brand new line of research or apply to a new Ph.D. program. This is likely why women who experience sexual harassment in the sciences often report lateral career moves, taking lesser jobs, continuing a working relationship with their perpetrator, or leaving science altogether (Nelson et al. 2017; RTI 2018). As one interviewee noted about her perpetrator:

Because I work in this area of the world and work at certain sites where he is pretty well known, it kind of became clear that I was going to have to play along a little bit of the political game where future research would have to…I’d have to be careful about how I interact with this person. . . . Because my research was now starting to be centered around this area and he had this reputation and everyone knew him. So I had basically an arm’s length professional connection with this person but then, also, he sort of started to be like as if he expected me to become the next mistress.” (Nelson et al. 2017, 715).

So to remain in particular work contexts that they otherwise feel an attachment to (e.g., locations in the world, particular field sites, particular disciplines), many

___________________

14 See http://www.newsweek.com/what-whisper-network-sexual-misconduct-allegations-719009.

women have to perform a very delicate dance of not angering their aggressor, even while trying to stay out of harm.

Two issues within these fields compound to make it difficult for women to have normal work experiences, or to report. Much of the scientific, engineering, and medical enterprise still presents itself as a meritocracy where the best trainees and young scholars get the best jobs, and the best jobs in science are often believed to be tenure-track, research-intensive academic jobs. The system of meritocracy does not account for the declines in productivity and morale as a result of sexual harassment. When a woman receives unwanted attention or experiences put-downs, it can make her question her own scientific worth. Additionally, it can make scientific achievement feel like it is not worth it:

Prior to the event I had hoped to be a number one scientist and go for a tenure professor position, or main research scientist, whereas now that is not in my scope. . . . So, I feel like I have refocused to more menial roles, perhaps staying as assistant research scientist as I have been doing, and now not stretching for anything greater. (Nontenure-track faculty member in geosciences)

The dependence on advisors and mentors for career advancement is another aspect of the science, engineering, and medicine academic workplace that tends to silence targets as well as limit career opportunities for both targets and bystanders. In a very real way, the academic pipeline is limited for women when their advisors or mentors are the perpetrators, or when those in supervisory roles are not understanding, supportive, or helpful when they disclose these experiences.

[The director] believed my story but he didn’t really know what to do. He was like, “In different cultures that’s not abnormal.” . . . He did talk to the guy, he just said that he needed to stay away from me and that I was feeling uncomfortable and I don’t know how much it worked, it was still weird. Because at night we’d have a fire, and he’d still find his way to come and sit next to me and sit there and try to put his arm around me and I’d tell him to stop and leave or I’d move so that I’m never around him. (Nelson et al. 2017, 713)

As described in Chapter 2, male domination is a feature of some disciplines even when those disciplines numerically have even or greater numbers of women. The “macho” culture of some disciplines, particularly those that involve isolating spaces such as labs, patient rooms, or field sites, puts women in harm’s way and creates a particularly permissive climate for sexual harassment. Women have shared that their colleagues at field sites feel the need to behave like “Indiana Jones,” and enforce this behavior in others. In particular, women who have been sexually harassed report a type of testing behavior common in their workplaces:

We would do these really, really long days but we wouldn’t be warned when they were coming, they would just happen and so I wouldn’t bring enough food. . . . And I would try to vocalize, “I am tired. I can’t go any further. I need to eat.” . . . The second time I spoke up, there was [sic] the other two girls who were quick

to say, “Yeah, we’ve been out a really long time, it’s 8:00PM, let’s go eat.” We started getting snide comments like, “Oh, well the ladies are hungry so I guess we have to leave.” (Nelson et al. 2017, 714)

Taken together, these aspects of the science environment tend to silence targets as well as limit career opportunities for both targets and bystanders. Targets of sexual harassment may also choose to attend fewer professional events or withdraw from the organization (Clancy et al. 2017), which has also been shown in other workplaces (Barling, Rogers, and Kelloway 2001; Cortina et al. 2002; Fitzgerald et al. 1997; Culbertson and Rosenfeld 1994; Glomb et al. 1999; Holland and Cortina 2013; Lonsway, Paynich, and Hall 2013; Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997; USMSPB 1995; Wasti et al. 2000). At the same time, it is important to note that at least some women who have been sexually harassed have been shaped by those experiences, choosing to fight harder for their students, do research in the area of gender discrimination, create better field-site policies, or speak up when they observe victimization (RTI 2018; Nelson et al. 2017).

Outcomes Connected with the Medical Environment

The pattern of consequences experienced by women in the workplace and in undergraduate and graduate settings repeats itself when examining the academic medicine environment. In a survey of female family practice residents in the United States, a significant number of those who were sexually harassed experienced the following negative effects, similar to the experiences of women in workplaces generally: poor self-esteem, depression, psychological symptoms that required therapy, and, in some cases, transferring to other training programs (Vukovich 1996). Women who experienced coercive sexual harassment reported feeling a loss of personal autonomy and control, humiliation, shame, guilt, anger, and alienation as a result of the harassment (Binder 1992). In another study, female physicians who recalled experiences of sexual harassment as medical students reported they had diminished interest in their studies (55.9 percent), recurrent intrusive memories of the abuse (30.5 percent), severe depression (23.7 percent), and considered quitting their medical studies completely (28.8 percent) (Margittai, Moscarello, and Rossi 1996). Female physicians who reported previous experiences of sexual or gender-based harassment in medical training were also more likely to report a history of depression or suicide attempts (Frank, Brogan, and Schiffman 1998).

In terms of professional and educational consequences, women in medicine yet again experience outcomes consistent with earlier findings in other environments. Women in medicine with lower career satisfaction were also found more likely to report previous experiences of harassment during medical training (Hinze 2004; Nora et al. 2002). Further, perceived mistreatment among women in medicine was associated with increased cynicism (Wolf et al. 1991) and a

lessened commitment to the profession (Lenhart et al. 1991). Finally, in a recent survey of physicians, of the respondents who reported being sexually harassed, 59 percent perceived a decline in their self-confidence, and 47 percent said that these experiences had an impact on their career path (Jagsi et al. 2016).

Impacts on the Integrity of Research

Research integrity relies on a set of ethical principles and professional standards that guide the behaviors of those involved in the research enterprise. The recent National Academy of Sciences report Fostering Integrity in Research (NAS 2017) lists six values that are most influential in shaping research integrity: objectivity, honesty, openness, accountability, fairness, and stewardship. Sexual harassment undermines at least three of these core values of research integrity. The first is accountability, which is defined as being “responsible for and stand[ing] behind their work, statements, actions, and roles in the conduct of their work” (NAS 2017, 34). More specifically, accountability for research supervisors means they are accountable for conducting themselves as professionals and for being attentive to the educational and career development needs of trainees. When a trainee is forced to leave a lab or program because his or her supervisor or a peer is a perpetrator and the supervising researcher does not stop the behavior, then the supervising researcher is violating the value of accountability.

The second value, stewardship, implies “being aware of and attending carefully to the dynamics of the relationships within the lab, at the institutional level, and at the broad level of the research enterprise itself” (NAS 2017, 36–37). This includes serving as mentors to young researchers and educating the next generation of researchers. If researchers are not aware and attending to issues of sexual harassment that are resulting in students, trainees, and early-career scholars missing out on events, opportunities, and the work of doing research, then they are not fulfilling the responsibility for good stewardship.

Finally, fairness in this context means “making professional judgments based on appropriate and announced criteria, including processes used to determine outcomes” (NAS 2017, 35). This seems the most obvious value that is violated by sexual harassment, since sexual harassment in the environments of science, engineering, and medicine are resulting in women being judged based on their gender, which is not an appropriate criteria. For example, when women scientists are told they are not the “right” person to go on field research trips, or when a senior researcher leaves the women students off the authorship list for papers or chooses only male students to work in his lab, the integrity of research is damaged because they are not upholding the value of fairness.

Given that sexually harassing behavior violates at least three key values of research, sexual harassment is damaging not just to targets and bystanders, but also to the integrity of science. The Fostering Integrity in Research report reflects this in its categorization of behaviors that affect the integrity of research. It states

that there are three categories of behaviors that affect research integrity: research misconduct, detrimental research practices, and other misconduct—and sexual harassment is included under other misconduct (NAS 2017).

The 1992 report Responsible Science put forward a framework of terms to describe and categorize behaviors that depart from scientific integrity [NAS-NAE-IOM 1992]. This framework was developed around the terms misconduct in science, questionable research practices, and other misconduct. (NAS 2017, 63)

Responsible Science identified a category of unacceptable behaviors that the panel termed other misconduct. These behaviors are not unique to the conduct of research even when they occur in a research environment. Such behaviors include “sexual and other forms of harassment of individuals; misuse of funds; gross negligence by persons in their professional activities; vandalism, including tampering with research experiments or instrumentation; and violations of government research regulations, such as those dealing with radioactive materials, recombinant DNA research, and the use of human or animal subjects.” (NAS 2017, 74–75)

The Fostering Integrity in Research report states that “this committee agrees that the category of other misconduct should remain as it was recommended in Responsible Science” (75).

Economic Impacts

The research described in this chapter demonstrates that sexual harassment can contribute to a woman’s intention to leave her job, among many other negative consequences. Though no formal economic analysis has yet put a specific dollar amount to the cost of women’s attrition from science, engineering, and medicine because of sexual harassment, the economic impact of scientists, engineers, and medical doctors opting to abandon research and practice in fields with high costs of entry is worth noting. Colleges and universities invest immense resources in training faculty and students in science, engineering, and medicine. One study (CHERI n.d.) calculated that start-up costs for new faculty in engineering and the natural sciences can range from $110,000 to almost $1.5 million, and when faculty leave the institution it can take up to 10 years to recoup the investment.

Though it is not currently known how many women leave faculty positions due to sexual harassment, we can infer from the research reviewed in this chapter that some women do leave institutions as a result of sexual harassment and that this loss is costly to individual institutions and to the advancement of knowledge. Federal and state agencies likewise invest heavily in the training and education of professionals in science, engineering, and medicine. Some have estimated the economic cost of a “newly minted” STEM Ph.D. at approximately $500,000. Multiplying this cost across all the women who leave science, engi-

neering, and medicine or suffer reduced productivity or advancement because of sexual harassment is likely to reveal a significant loss of taxpayer dollars. A full assessment of the economic impact of sexual harassment in science, engineering, and medicine will first require a deeper understanding of the nature of the negative impacts of sexual harassment in these fields. Attrition from school or work, reduced productivity (of individuals and teams of researchers and students), barriers to advancement, and mental health concerns can each carry economic consequences. Additional research on the prevalence and impact of sexual harassment in science, engineering, and medicine could facilitate a formal economic analysis of the costs of harassment that would offer important new insight.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

-

Sexual harassment undermines women’s professional and educational attainment and mental and physical health. Negative outcomes are evident across lines of industry sector, occupation, race, ethnicity, and social class, and even when women do not label their experiences as “sexual harassment.”

- When women experience sexual harassment in the workplace, the professional outcomes include declines in job satisfaction; withdrawal from their organization (i.e., distancing themselves from the work either physically or mentally without actually quitting, having thoughts or intentions of leaving their job, and actually leaving their job); declines in organizational commitment (i.e., feeling disillusioned or angry with the organization); increases in job stress; and declines in productivity or performance.

- When students experience sexual harassment, the educational outcomes include declines in motivation to attend class, greater truancy, dropping classes, paying less attention in class, receiving lower grades, changing advisors, changing majors, and transferring to another educational institution, or dropping out.

- Gender harassment has adverse effects. Gender harassment that is severe or occurs frequently over a period of time can result in the same level of negative professional and psychological outcomes as isolated instances of sexual coercion. Gender harassment, often considered a “lesser,” more inconsequential form of sexual harassment, cannot be dismissed when present in an organization.

- The greater the frequency, intensity, and duration of sexually harassing behaviors, the more women report symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety, and generally negative effects on psychological well-being.

- The more women are sexually harassed in an environment, the more they think about leaving, and end up leaving as a result of the sexual harassment.

- The more power a perpetrator has over the target, the greater the impacts and negative consequences experienced by the target.

- For women of color, preliminary research shows that when the sexual harassment occurs simultaneously with other types of harassment (i.e., racial harassment), the experiences can have more severe consequences for them.

- Sexual harassment has adverse effects that affect not only the targets of harassment but also bystanders, coworkers, workgroups, and entire organizations.

- Women cope with sexual harassment in a variety of ways, most often by ignoring or appeasing the harasser and seeking social support.

- The least common response for women is to formally report the sexually harassing experience. For many, this is due to an accurate perception that they may experience retaliation or other negative outcomes associated with their personal and professional lives.

-

Four aspects of the science, engineering, and medicine academic workplace tend to silence targets as well as limit career opportunities for both targets and bystanders:

- The dependence on advisors and mentors for career advancement.

- The system of meritocracy that does not account for the declines in productivity and morale as a result of sexual harassment.

- The “macho” culture in some fields.

- The informal communication network, in which rumors and accusations are spread within and across specialized programs and fields.

- The cumulative effect of sexual harassment is significant damage to research integrity and a costly loss of talent in academic science, engineering, and medicine. Women faculty in science, engineering, and medicine who experience sexual harassment report three common professional outcomes: stepping down from leadership opportunities to avoid the perpetrator, leaving their institution, and leaving their field altogether.

This page intentionally left blank.