3

Strategic Use of Information

Presenters in this panel brought three different perspectives to bear on cyber policy and security. Herb Lin, Stanford University, discussed cyber-enabled information warfare and influence operations; Jacklyn Kerr, also of Stanford University, examined Internet regulation in authoritarian governments; and Richard Harknett, University of Cincinnati, addressed the use of strategic cyber persistence. Suzanne Fry, National Intelligence Council, then offered comments on these presentations and their implications for future research. The panel closed with an open discussion between presenters and audience members.

CYBER-ENABLED INFORMATION WARFARE AND INFLUENCE OPERATIONS

Lin framed his presentation with the question, “What would Hitler have been able to do with the Internet?” Information warfare and influence operations, he explained, denote the “deliberate use of information to confuse, mislead, and affect the choices and decisions” of an adversary. Although hostile, he added, they do not represent warfare in the traditional sense as defined by the United Nations Charter or laws of armed conflict. Noting the juxtaposition between the terms “information,” which implies propaganda and persuasion, and “warfare,” which suggests armed conflict, he quoted Sun-Tzu, author of The Art of War: “The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.” He noted that cyberwar is categorized as either (1) high-level (crippling society as a whole, attacking critical infrastructure, or destroying weapons systems); or (2) low-level

(drug dealing, child pornography, hacktivism, credit card fraud, and theft of intellectual property).

According to Lin, information warfare has “its own battle space and theory of operations.” He explained that conflict takes place in the information environment of cyberspace and involves the cognitive and emotional parts of the brain. He added that victory in information warfare and influence operations is when the adversary willingly accepts and adopts the victor’s political goals not because the adversary no longer has the means to resist (e.g., if it were militarily defeated), but because the adversary no longer views the victor as the enemy. Knowledge, truth, and confidence are all damaged, he continued, as the result of infection of the adversary’s decision process with fear, anger, and uncertainty. Furthermore, he asserted, there are no noncombatants in information warfare and influence operations; everyone, including governments, universities, and news media, is a potential target.

Lin outlined ways in which creating chaos and confusion can be damaging to a state adversary. First, he suggested, it creates conflict and uncertainty in the targeted state, and this internal conflict also harms the state’s international reputation. Moreover, he added, a state is unlikely to take action in response to information warfare and influence operations because they fall below the “act of war” threshold. He noted that, if the attacking state chooses to identify itself as responsible for such an act, the act is classified as being a “white” operation; if the identity of the responsible group is unclear, the act is considered a “gray” operation; and if another party is blamed, the act is regarded as a “black” operation.

Lin also described three main types of information warfare and influence operations. The first, propaganda, disseminates false information to influence attitudes and opinions. Information developed to reach a wide audience, Lin explained, often consists of a simple and repeated lie that appeals to emotions rather than reason; he likened this to the approach used in Hitler’s Mein Kampf. The second type is a chaos-producing operation. With this method, Lin explained, a high volume of false messages, such as trolls’ posts about fabricated disasters, is released rapidly to the public. The messages, he noted, need not be consistent or have a purpose. The third type, a leak operation, involves leaking secret and often embarrassing or compromising information to the public.

Lin noted that, while information warfare is old, cyber-enabled information warfare is relatively new and has several advantages. For example, he said, it is inexpensive and easy to disseminate the information to a wide audience. Thus, he added, even small groups can have a loud voice. Moreover, he observed, this form of warfare is often legal and can reach international audiences, and it is not difficult for the attacking actor to remain anonymous. Furthermore, marginalized communities can locate one

another and join forces to become more powerful. For example, Lin noted, automated Twitter accounts can amplify messages. He explained that information warfare and influence operations take advantage of the advertised features of information technology, whereas cyberwar takes advantage of the virtues of information technology.

According to Lin, it is human cognitive and emotional biases that help information warfare and influence operations work. To illustrate, he pointed out that fluency bias and illusory truth bias allow simple and repeated messages to be received positively; confirmation bias causes people to seek out only information that is already in line with their beliefs; and emotional bias prevents people with strong emotional beliefs from considering rational arguments.

Lin noted that some interest in policy changes has resulted from Russia’s interference with the 2016 presidential election. He asserted that the main consequence of this interference was that it increased political tensions in the United States. However, he added, this would likely have happened regardless of which party won the election. Because of the current polarizing political environment and the nation’s poor cyberdefense policies, he argued, the United States is particularly vulnerable to this form of information warfare and influence operations. In his view, moreover, the U.S. military does not always value soft power and often mistrusts people working in information operations.

To respond to information warfare, Lin continued, it is important to identify its targets. If the U.S. government can do a better job of identifying who is being attacked, he suggested, it may be able to do better at identifying when an attack is taking place. Moreover, he argued, for the United States to counter information warfare and influence operations, it must first recognize what will not help. He cited two strategies that are too time consuming to be effective: utilizing “traditional institutions that require coordination” and recruiting “smarter and better-educated people.” On the other hand, he suggested, it may help if the United States can drown out the attacking actor with countermessages. He referred to some research indicating that promoting the truth is more effective than attempting to refute false information. He suggested further that the United States may want to initiate more gray operations against perpetrators. He added that the private sector has been working on these issues and should be encouraged to continue those efforts.

Lin also observed that it is especially difficult to use information warfare against authoritarian regimes. Such regimes usually have strict information control systems that limit the types of communication citizens can access.

Lin closed by noting that there have been discussions related to striking a “grand bargain” with U.S. adversaries, according to which the United

States would make concessions in return for an end to information warfare. However, he acknowledged that he is unsure whether this is a real possibility.

INTERNET CONTENT, INFORMATION CONFLICT, AND THE FUTURE OF FREE EXPRESSION

Kerr drew on her work on the Internet and society to argue for continuing research on how authoritarian regimes are evolving in the information age and what the implications are for national and international security. She began by recalling the mass election protests that occurred in Russia in 2011 and 2012, which the country’s leadership regarded as an existential threat. She noted that the protesters relied heavily on relatively new information technologies to mobilize fellow citizens, demonstrating the usefulness of these technologies in mass protests.

Kerr added that many people, especially in the West, regarded these new technologies as vital supports for liberty, a tendency she referred to as “cyber utopianism.” The Internet allowed people to communicate in ways that were not possible through such traditional channels as print and radio or in media environments that were sometimes highly constrained. However, Kerr noted, authoritarian states threatened by this method of discourse initiated regulations making it more difficult for citizens to communicate freely using the Internet. In response to such authoritarian clampdowns, political figures, such as Hillary Clinton, began publicly advocating for Internet freedom as a democratic freedom and individual right.

These issues have only become more complex in the years since the protests in Russia, Kerr continued. She explained that increases in viral propaganda, extremist content, and hate speech and such developments as the 2016 hack into the Democratic National Committee’s computer system have heightened attention to the need for greater Internet security and stability. She believes there is much to be learned from a close look at evolving approaches to the flow of information within authoritarian states.

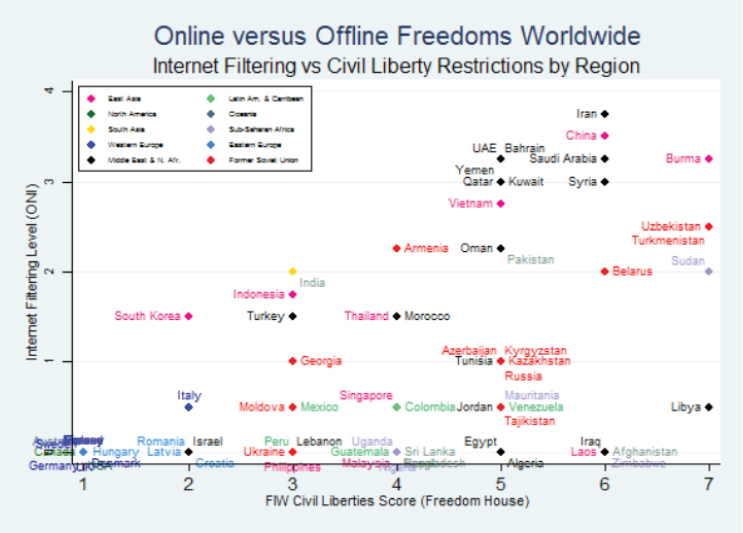

The Internet has changed dramatically in its short life, Kerr observed. At first, she elaborated, it was regarded as a technology that could not be censored, but by 2010 a variety of technical and nontechnical means for doing just that had been developed. She reported that researchers at The Citizen Lab, a project at the University of Toronto,1 have measured blocking of content on the Internet and linked it to other forms of repression; their findings are shown in Figure 3-1. The countries on the far right of the figure are the most repressive overall, she explained, but the relationship between censorship and other repression is not always predictable. The

___________________

1 For more information, see https://citizenlab.ca [January 2018].

SOURCE: Kerr, J. (2014). The Digital Dictator’s Dilemma: Internet Regulation and Political Control in Non-Democratic States. Palo Alto: The Center for International Security and Cooperation, Stanford University. Used with permission.

researchers found, for example, that in some states of the former Soviet Union, there was far greater freedom online than elsewhere in society. How might one account for differences between those states and others, such as China, Qatar, or Saudi Arabia, which adopted more restrictive approaches to the Internet from the outset?

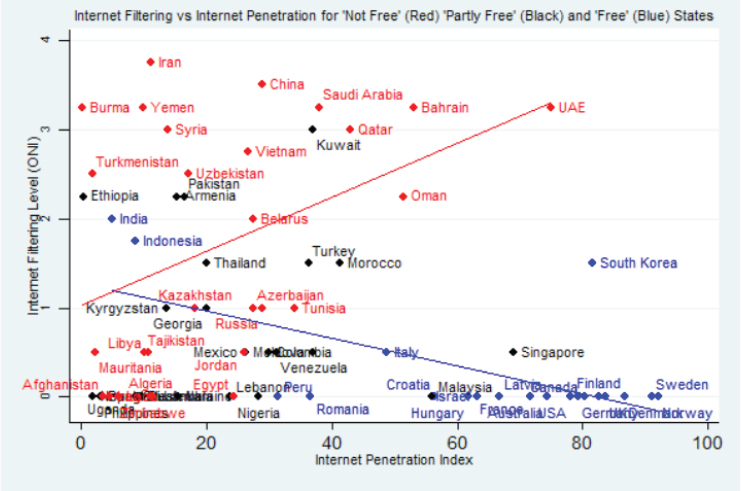

Kerr highlighted two seemingly conflicting trends that shed light on this question. Pointing to Figure 3-2, she explained that, as general Internet penetration increased, the most authoritarian states (shown in red) tended to converge on a norm of relatively high censorship because of the risks they perceived, such as mass protests or regime change. The states with the greatest degree of general freedom, shown in blue, tended to converge in choosing not to censor political and social content on the Internet. In the middle were states that fit neither category and were also relatively late to achieve Internet penetration. These countries, Kerr explained, faced conflicting pressures as they made decisions about censorship. Although they perceived threats in the form of protest movements, they also allowed some democratic freedoms, so they risked being labeled as hypocritical if they violated those freedoms by censoring the Internet.

SOURCE: Kerr, J. (2014). The Digital Dictator’s Dilemma: Internet Regulation and Political Control in Non-Democratic States. Palo Alto: The Center for International Security and Cooperation, Stanford University. Used with permission.

Some of these latter states did impose increased censorship, Kerr continued, but others adapted. She explained that, instead of adopting such overt censorship practices as site blocking and keyword filtering, methods used in the Great Firewall of China since the early 2000s, some countries adopted next-generation approaches that were more subtle and could be denied more plausibly. Table 3-1 lists examples of these two different approaches to censorship. In Russia, for example, Kerr reported that new forms of control over the Internet and information flow included pressure on information technology businesses, improved surveillance capabilities, and the generation of new sorts of targeted content not readily identifiable as propaganda.

Kerr emphasized that these developments blurred the line between censorship and noncensorship, the Chinese and democratic approaches. She acknowledged the spectrum between these two poles, but suggested that limited censorship using less overt tools and in a context of legal and security justifications represents a third approach. The old paradigm, she explained, was of a dichotomy between, on the one hand, a vision of global Internet universalism, according to which access to the Internet is a right

and democratic norms of free expression are valued, and, on the other hand, a focus on national cybersecurity with reliance on a range of methods to contain threats. She added that information itself is viewed as a threat to security in Russia and other countries. Russia, she noted, introduced an “information security doctrine” in 2000, just after Vladimir Putin had confronted some very negative publicity about the sinking of a Russian submarine. This doctrine identified both independent Russian media and foreign media as a threat and was part of a gradual media crackdown. The doctrine was updated in 2016 to mention the Internet explicitly, Kerr added.

Similar concepts have been promoted elsewhere, Kerr continued, including in a United Nations code of conduct for information nonaggression. “You see this way of thinking about information being rolled out in military and strategic thought and applications,” she commented. Leaks and targeted propaganda, she suggested, are being used as part of toolsets that also include cyberattacks, hacking, and other more technical forms of aggression that are used in domestic and international contexts. The goal of such efforts, she explained, is to exploit the vulnerabilities of groups or coalitions by “changing the narrative, rather than by blocking information.” Although those who use these strategies create the illusion that information flows freely, she added, the result is in fact increased control of information.

Kerr identified several pressing research needs in this area. The vulnerability of democratic systems to these new threats needs to be studied, she asserted, and the concept of soft power reexamined in the post–Cold War digital context. She suggested that authoritarian regimes may be more resilient than their democratic counterparts because they have been ad-

TABLE 3-1 Two Approaches to Internet Restriction

| “First Generation” | “Next Generation” |

|---|---|

| Site blocking Keyword filtering Manual censorship of content Cellular or network shutdowns Network traffic slowdowns “Walled garden” intranets |

Restrictive legal measures Informal takedown requests Regulation of private companies Just-in-time blocking/DDoS attacks Patriotic hacking/trolling/blogging Targeted and mass surveillance Economic takeovers Trials/physical attacks |

NOTE: DDoS = distributed denial of service.

SOURCE: Adapted from slide created by Jacklyn Kerr for the workshop.

dressing these issues for 20 years. She also highlighted the need to develop ways of addressing these challenges without violating democratic values. She suggested further that cyberconflict cannot be thoroughly understood through a framework of deterrence and military conflict, arguing that interdisciplinary work incorporating insights from media theory and the study of state–society relations, public opinion, protest movements, government processes, and other relevant areas is needed.

CYBER PERSISTENCE: RETHINKING SECURITY AND SEIZING THE STRATEGIC CYBER INITIATIVE

Harknett began by asking the audience to imagine that it was May 8, 1945, and World War II had just ended. He then argued that all of the tactics, operations, and strategies used to secure that victory would now become secondary. A radical new concept in international security—deterrence—would be needed instead, and it would require the U.S. Congress to spend trillions of dollars on military capabilities that would be developed with the sole purpose of never being used. Although this argument would have seemed outlandish on the day of victory in World War II, Harknett pointed out that this radical new concept was soon accepted.

Harknett used this scenario to illustrate the misalignment between current thinking about security and the realities of cyberconflict. He likened the situation today to paradigm shifts that occur in science, as described by Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, because he believes experts are resisting the implications of the empirical data they are seeing. “If we don’t get our fundamental assumptions [about the] strategic environment right,” he argued, “then the intelligence requirements, the capabilities that we need to have to do the necessary intelligence to engage in these types of operations are going to be completely out of whack.” To demonstrate this strategic misalignment, he pointed to an executive order on cybersecurity recently signed by President Trump, which asks “How are we going to deter?” rather than “How are we going to secure?”

Harknett asserted that, just as the destructive power of nuclear weapons made traditional defense strategies obsolete, the potential dangers of cyberspace make traditional deterrence obsolete. He suggested instead a strategy of cyber persistence, an approach that is not just tactical or operational but also takes into account the capabilities and actions of state and nonstate actors, large and small. He observed that in 1914, for example, it was assumed that going on the offensive provided an advantage, and even the data from the conflict at Verdun during World War I (in which 750,000 casualties were incurred over 10 months for the sake of a quarter-mile advance) did not immediately undermine that assumption.

Turning to defense in a cyber context, Harknett argued that it has little

cumulative effect on the overall scale and scope of an adversary’s capability. One can remove malware, for example, but the adversary can quickly reengineer it and find a new pathway for its operation.

Neither offense nor defense is particularly helpful in a cyber context, Harknett asserted. Instead, he argued, the focus should be on the interconnectedness of both strategies and organizations, not particular segments of a situation or environment. Cyberspace is not a “war-fighting domain,” he suggested, although the military may be viewing it that way. Rather, he said, it is “an interconnected domain in which the military may have to fight.” He suggested that national security experts view the situation not as a traditional chess board but as a constantly shifting terrain resembling Figure 3-3.

Harknett concluded his presentation by stating that a focus on cyber persistence has challenging implications for the Intelligence Community (IC). He used wrestling as an analogy to replace the offense/defense framework: “If you come at me and I use your weight as momentum and shift and then pin you, was I playing offense or defense? If I let you into my network or you get into my network but I know you’re in my network and I start to follow you, and then use that reconnaissance to understand how I can vector back and take that capability away from you, was I playing offense or defense?” Thus analysts must simultaneously anticipate potential exploitation of vulnerabilities on their side while leveraging the vulnerabilities of adversaries. Those vulnerabilities may not all be technical, Harknett added; as the earlier presentations had suggested, open democratic societies have vulnerabilities that authoritarian ones do not.

In sum, Harknett asserted, cybersecurity will depend on seizing the initiative across the full range of tactics and operations. It will require a “national-level strategy that encompasses resilience, defense, and countercapability in an environment of constant action and universal vulnerability.” According to Harknett, the United States must move away from deterrence as the cornerstone strategy for managing cyberspace; it should focus on a strategy of persistence. He believes the need for this shift will only become more pronounced as the next technology leap occurs. He agreed with a statement by Vladimir Putin that whoever controls artificial intelligence will control the future of international dynamics, and noted that China has a grand strategy for translating cyber capabilities and artificial intelligence into strategic advantages, whereas the United States does not.

REMARKS FROM SUZANNE FRY

Fry began her remarks by observing that information has become such a part of the environment that it is like air or water. Thus she suggested that, when researchers think about addressing cyber issues strategically, they “not aim for a cyber grand strategy,” but “for a grand strategy given

SOURCE: Created by Richard Harknett for the workshop.

an environment in which information is now like oxygen.” She stressed the need to understand not just the context of strategy “but actual strategy . . . both in a geopolitical sense as well as in a sort of defensive domestic sense.”

Fry agreed with the point made by Lin in his presentation that influence campaigns are driven by emotions. However, she urged researchers to consider how the Internet may be changing the way people feel and behave. She would also like to know how the Internet is used to manipulate people.

Fry observed further that, although information warfare and influence operations are not truly considered warfare in the traditional sense, when taken as a whole they represent attempts by another power to assert dominance. She posed the question, “How do we get our arms around the cumulative effects of this particular tool?” She argued for the need to develop methods with which to measure the effects of information warfare and influence operations, as well as for the need to know whether those effects are marginal or not.

Fry then noted that the military often thinks about an adversary’s “cen-

ter of gravity,” which, she said, includes “will to fight, will to support, civic commitment to country,” and other “core issues of national loyalty not just among warfighters, but also the citizenry.” If the purpose of influence operations is to disrupt the center of gravity, she asserted, researchers need to design ways to measure the outcomes.

According to Fry, another area of interest to the IC is interconnectedness as it relates to the Internet. She pointed out that, although the Internet was created more than two decades ago, little is still known about how it is associated with feelings of peace, love, or tolerance or with fragmentation, conflict, and intolerance. She suggested that more research is needed on this topic.

Turning to Kerr’s presentation on authoritarian governments, Fry suggested that it would be helpful if the IC knew how countries decide what information should be blocked. She also wondered whether there is an economic cost to the authoritarian strategy. She suggested that research is needed to determine whether censorship inhibits the ability to accumulate wealth.

Finally, returning to the topic of strategy, Fry suggested that it would be helpful to have “predictions about the patterns of geopolitical competition” and “how those strategies might evolve in the strategic environment.”

DISCUSSION

An audience participant opened up the panel discussion by suggesting that cyber issues may be one space in which alliances between state and nonstate actors are likely. Lin responded by noting that when the First Amendment was enacted information was scarce. At the time, he said, it was thought that the “best antidote to bad information is more information.” Although access to information is no longer an issue, he continued, the United States is founded on the principle of free speech, which serves to inhibit government action in this area. However, he noted, private industry is not subject to the same constraints as the government. Thus, if there is a solution, he asserted, it will likely be found in the private sector.

Harknett suggested that public–private partnerships are a possibility, but the goals and motives of each partner need to be aligned if progress is to be made. According to Kerr, the Internet has changed the way protesters, bloggers, and other groups communicate and organize in authoritarian governments. She also agreed with Lin’s comments about the significance of private-sector actors. There have been moments, she observed, in which public speech has been harmful both to individuals and to society in general. In those moments, she said, private organizations have taken steps to limit speech, a move that changes their role in security issues in democratic settings.

Another topic that arose during the discussion involved interdisciplinary work. An audience member asked what concepts, theories, and methods the fields of political science and security studies should borrow from other disciplines to address cybersecurity issues. Lin replied that the number of disciplines that could work together on these issues is endless. He noted that issues of cybersecurity cut across all fields because “when you’re talking about cybersecurity, you’re talking about the integrity and reliability of information in every field.”

Kerr agreed that a multitude of disciplines could work together on cybersecurity issues. First, she suggested, much can be accomplished with the combination of sociology and big data. She observed that such methods as computational linguistics and content and topic analysis, combined with network analysis, have been used in the past to study longitudinal changes and topics that span various networks. She also called attention to work based heavily in quantitative methods that she asserted could benefit from understanding culture and history. In her own work, she reported, she has been examining methodologies from science technology studies.

Harknett suggested that, instead of thinking about core concepts, it may be more important to consider how to bring members from different fields together. He gave the example of specialists in security studies working more closely with computer scientists. However, he added, organizational research could be used to answer questions about leveraging the expertise of these two disciplines.

An audience member observed that much of what had been discussed during the panel had centered on the spread of ideas across networks, which is somewhat analogous to the way diseases spread. With that analogy in mind, this participant asked whether the panelists thought there might be a way to link epidemiological methods to cyber issues. Lin responded that this is an idea advanced by other researchers, as well as incorporated in models from various disciplines, such as environmental studies. He added that some researchers are actively looking to such disciplines as epidemiology for solutions.

Harknett followed up on Lin’s comments by adding that, while models are being drawn from epidemiology and environmental studies, it is important to remember that strategic actors in cyberspace are often purposely attempting to do harm. Viruses and bacteria may hurt us, he added, but they are motivated by survival rather than malicious intent.

Kerr expressed her interest in these analogies. She stated that she is particularly interested in comparison with sustainability from the environmental movement, as well as sustainable business practices. She agreed that Harknett’s point about strategic intent is an important one, but suggested that its salience depends on the type of cyber issue being studied.