1

Introduction: Evaluation Scope and Approach

BACKGROUND

Since 2004, the U.S. government has provided support for global HIV programs through an initiative known as the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). As the largest bilateral donor to the global response to HIV, PEPFAR is a multifaceted and complex initiative. Working through many partners, including country governments and nongovernmental organizations, PEPFAR supports a range of activities, such as direct service provision, programmatic support, technical assistance, health systems strengthening, and policy facilitation. These activities are implemented in the cultural, social, economic, and political landscape of each partner country, and in the presence of HIV and health programs supported by other domestic and donor funding sources. These efforts have contributed to saving and improving the lives of millions of people around the world (IOM, 2013).

As the focus of global and national responses to the epidemic transitioned from an urgent need to scale up HIV services to sustainability and country ownership of HIV programs, strengthening components of the broader health system, such as human resources for health (HRH), remained crucial for delivering services and achieving better health outcomes (Palen et al., 2012). The Joint Learning Initiative, the World Health Report 2006, and the Global Health Workforce Alliance all highlighted the increasing HRH shortage, most acute in countries heavily affected by HIV, and called for greater investments in health workers. This included scaling up education and training to boost the number of qualified health work-

ers, as well as addressing skills mix imbalance, retention, migration, and maldistribution (Chen et al., 2004; Palen et al., 2012; WHO, 2006; WHO and GHWA, 2008). PEPFAR’s HRH strategy between 2008 and 2014 also incorporated innovative health service delivery models, such as task shifting and use of quality improvement interventions, as well as regulation of providers (PEPFAR, 2015). Among HRH initiatives that emerged as a result, three PEPFAR-funded efforts—the Medical Education Partnership Initiative, the Nursing Education Partnership Initiative, and the General Nursing Project—played important roles in expanding the workforce of physicians, nurses, and midwives and the capacity of health professional education institutions in Africa.

The Republic of Rwanda has been a PEPFAR partner country since the beginning of the initiative.1 Rwanda has made steady improvements in its response to HIV, with increasing access to and coverage of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and a steady decrease in HIV prevalence (Nsanzimana et al., 2015; UNAIDS, 2018a). Government leaders in Rwanda have long advocated for equity, integrated service delivery, and systems strengthening in the health sector (Binagwaho et al., 2014; Nsanzimana et al., 2015). However, despite gains in the response to HIV and in other key population health indicators since the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi, Rwanda has a health worker density of just 1.1 per 1,000 population for physicians (0.1 per 1,000), nurses and midwives (0.7 per 1,000), and other health workers (0.3 per 1,000) combined (Open Data for Africa, 2018)—far below the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended minimum of 4.45 skilled health workers per 1,000 population (WHO, 2016).

RWANDA HUMAN RESOURCES FOR HEALTH PROGRAM

Reflecting a prioritization of HRH in Rwanda, the HRH Program was originally designed as an 8-year program (2011–2019) to respond to four key barriers the Rwandan government had identified as preventing the provision of high-quality health care: (1) a shortage of skilled health workers; (2) poor quality of health worker education; (3) inadequate infrastructure and equipment for health worker training; and (4) inadequate management across different health facilities (MOH, 2011). The HRH Program, which was designed, managed, and implemented by the Rwanda Ministry of Health (MOH), sought to remedy these issues by partnering with U.S. medical, nursing, dental, and public health training institutions to build institutional capacity at the University of Rwanda College of Medicine and Health Sciences (CMHS) and to augment and increase the capacity of the

___________________

1 United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act of 2003, P.L. 108-25, 108th Cong., 1st sess. (May 27, 2003).

country’s health care workforce (Binagwaho et al., 2013; Cancedda et al., 2017; Uwizeye et al., 2018).

In addition to PEPFAR funding, primarily through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Program was supported by other major funders, including the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; the Rwandan MOH; and, to a lesser extent, other entities (Cancedda et al., 2018). In 2015, PEPFAR adopted a new strategy that required country programs to focus resources in high-burden geographic areas and on key populations (PEPFAR, 2014). The strategy resulted in a reconfiguration of PEPFAR’s HIV portfolio in Rwanda and a decision not to continue funding the Program (PEPFAR Rwanda, 2015).

HRH Program Framework

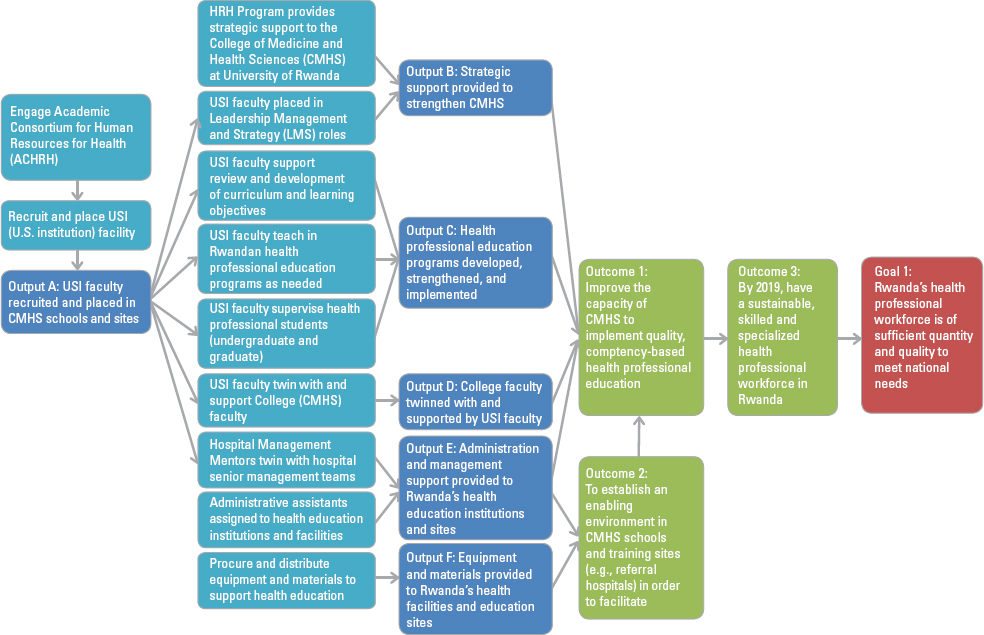

The Program framework (see Figure 1-1)2 describes the ultimate goal of the HRH Program, which was to “upgrade Rwanda’s health professional workforce to be of sufficient quantity and quality to meet the national need” (MOH, 2014). The Program proposed a number of ambitious workforce expansion targets by cadre:

- Nearly double the number of physicians (from 633 to approximately 1,182) in 8 years (MOH, 2011).

- More than triple the number of specialty physicians (from 150 to 551).

- Increase the overall size of the nursing and midwifery workforce by 25 percent (Binagwaho et al., 2013).

- Increase the proportion of nurses with advanced certificate training by more than 600 percent.

- Increase the number of trained professional health care managers from 7 to 157, so each district, provincial, and referral hospital could be professionally managed (Binagwaho et al., 2013; MOH, 2011).

To accomplish its goal, the HRH Program was designed to include numerous activities. U.S. medical and health professional universities provided instructors for Rwanda’s new health educational and training programs, filled gaps in teaching rosters for existing programs, and supported Rwandan educators in the development of new curricula and professional training programs (Cancedda et al., 2017, 2018; Uwizeye et al., 2018). A

___________________

2 The HRH Program Framework is taken from the Program’s 2014 monitoring and evaluation plan (MOH, 2014). It is presented here unaltered. It reflects the whole of the Program, which includes PEPFAR, the Global Fund, and other financial investments.

NOTE: CMHS = College of Medicine and Health Sciences; USI = U.S. institution.

SOURCE: MOH, 2014.

twinning program, pairing Rwandan and U.S. institution (USI) faculty and professionals, sought to build knowledge, promote the transfer of clinical and teaching skills, and facilitate research collaboration (Binagwaho et al., 2013; Cancedda et al., 2018; Ndenga et al., 2016). In addition, the HRH Program’s hospital quality improvement projects assigned faculty from USIs to hospitals to build leadership capacity (MOH, 2016). Other important efforts to build the institutional capacity of Rwanda’s medical and health professional institutions under the HRH Program included upgrading equipment and infrastructure at teaching facilities and training professional health managers (Cancedda et al., 2018). To make teaching a more attractive career option, the Program proposed a variety of structural and policy changes, including a new career laddering system within health cadres (MOH, 2011).

The HRH Program was fully managed and operationalized by the Government of Rwanda. The MOH set up a new management and advisory infrastructure to run the Program. It received direct U.S. and other donor funding and expended these funds, in part, through contracts with U.S. medical and health professional institutions that, as part of an academic consortium of 22 USIs, had been selected to provide faculty and health professionals to implement capacity-building and workforce-strengthening activities (Binagwaho et al., 2013; Cancedda et al., 2017, 2018).

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

The Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) was asked to undertake an evaluation of the HRH Program through a single-source request for application from CDC (CDC-RFA-GH18-1850). The National Academies had been called on previously to evaluate the implementation and impact of PEPFAR programs (IOM, 2007, 2013). Box 1-1 presents the full Statement of Task, as provided by CDC and the Department of State’s Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and approved by the Governing Board of the National Academies.

In response to this request, the National Academies appointed a committee of experts to carry out the evaluation as a consensus study. The committee was a multidisciplinary group of experts, selected based on their relevant knowledge and experience, expressly for the purpose of conducting this evaluation. Members had expertise in health workforce and health professional education, HIV clinical care and service delivery, health care quality, health services research, mixed-methods research, epidemiology, biostatistics, and health economics. See Appendix A for more information about the committee.

The design and operationalization of this evaluation was conducted in accordance with specific National Academies policies and procedures that

are in place to assure neutrality and objectivity for its consensus studies. Therefore, the study committee, staff, and evaluation team explicitly did not include any individuals who were affiliated with the sponsor of the evaluation, the funders of the program being evaluated, the implementers of the program, or parties with any other conflict or perceived conflict of interest. Given the wide reach of the HRH Program in Rwanda, and overlap with most individuals in fields of expertise and professional roles related to both health professional education and health service delivery, the committee did not have any members who were from Rwanda. Members of the committee had experience in clinical care, HRH, and health professional education in Rwanda and throughout the region.

An advantage to the use of an external evaluator is that it optimizes objectivity and neutrality in the evaluation design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and it provides assurance that the resulting conclusions and recommendations have not been vetted or controlled by those closely affiliated with or affected by the subject of the evaluation. A disadvantage

of an external evaluation can be that the evaluators do not inherently have the depth of context or the first-hand knowledge and insight of those who were directly involved. To enable appropriate interpretation of the available evidence and to foster the generation of meaningful conclusions and useful recommendations, it is important to incorporate this perspective and experience.

This evaluation incorporates several elements designed to accomplish this. First, a range of data sources were used to gather information about the context in which the HRH Program operated, as called for in the Statement of Task. The evaluation design also included the participation, through qualitative methodologies, of stakeholders with direct knowledge of the context and first-hand experience of the Program. Furthermore, in addition to study committee members with experience working in Rwanda, the evaluation team who carried out data collection and analysis included members who are Rwandan and contributed their contextual understanding. More broadly, stakeholders close to the Program in Rwanda had the opportunity to participate in public meetings, held in Kigali in December 2018 and May 2019, and provide additional context on HRH and HIV in Rwanda. Several points during the operational planning phase of the evaluation also provided opportunities for cooperation with key parties involved in the implementation of the Program, primarily the MOH and PEPFAR Rwanda.

Before its public release, the report underwent a thorough review by independent reviewers with expertise in HRH, HIV, and other subjects and methods relevant to the evaluation. Among these reviewers were individuals from Rwanda. However, consistent with National Academies’ policies protecting the independence of the committee’s work, the sponsor and key parties involved in the HRH Program neither reviewed preliminary findings, conclusions, and recommendations nor changed the draft report before its public release as a final document.

COMMITTEE’S APPROACH TO THE CHARGE

Overview

In response to the Statement of Task, the evaluation applied a retrospective, concurrent mixed-methods design, drawing on literature and document review, qualitative interviews, and secondary analysis of quantitative data. Chapter 2 describes the design and methodology in more detail. By drawing on multiple complementary data sources, the design provided flexibility to capture what results had occurred, while gaining a deeper understanding of how the gains were achieved and why change did or did not happen. This design also enabled insight into how different stakehold-

ers, implementers, participants, and beneficiaries experienced the HRH Program and its effects.

The committee used a contribution analysis approach that focused on the potential contributions to observed outcomes by understanding how the Program and its components were implemented and what effects they produced, and by examining the contextual factors that may have enhanced, moderated, or otherwise influenced outcomes (Moore et al., 2014). The analysis of the effects of the Program was informed by a theory-based causal pathway, described under the section “Theoretical Framing,” that reflects how programmatic activities and resulting changes in HRH outputs could be reasonably expected to contribute to intermediate HRH and health outcomes for people living with HIV (PLHIV).

The evaluation also employed appreciative and utilization-focused principles and a socioecological framework. Appreciative approaches in evaluation are effective in identifying often unrecognized programmatic results from the perspectives of diverse stakeholders, and in determining strengths on which to build for future efforts (Preskill and Catsambas, 2006). A utilization-focused approach ensures insights are grounded in the realities of those closest to a program and is more likely to provide useful and realistic recommendations to inform future activities and investments in HRH for HIV in Rwanda and elsewhere (Patton, 2008). Applying a socioecological framework provides a lens through which to view how different levels (individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and policy) interact and influence outcomes separately and as part of a larger system (McLaren and Hawe, 2005).

Evaluation Scope and Time Frame

The charge to the committee was to focus on PEPFAR investments in the HRH Program. The use of PEPFAR funding was difficult to isolate in this Program, which was implemented through an integrated financing stream that drew from multiple combined funding sources (described further in Chapter 3). Therefore, the evaluation focused on activities within the Program that were supported, although not exclusively, by PEPFAR. These included building health professionals’ capacity to train HRH in nine clinical and management specialties (anesthesia, emergency medicine, internal medicine, nursing and midwifery, obstetrics and gynecology, pathology, pediatrics, surgery, and hospital administration) and investments in equipment.

The evaluation focused on the activities carried out during the years when the HRH Program received PEPFAR-supported funding (2012–2017), also taking into account ongoing and lasting effects of those activities and the effects of the 2015 decision not to continue PEPFAR funding through 2019.

Theoretical Framing

Theoretical causal pathways facilitate understanding of how complex interventions plausibly contribute to more distal outcomes and show the processes undertaken to achieve those outcomes. Investments to expand health professional education and training capacity ultimately aim to contribute to improved health outcomes, although different capacity-building strategies vary in their timeliness of impact, in terms of both outcomes for health professionals and population health outcomes (WHO and GHWA, 2008). There are several pathways by which investments in HRH capacity could yield improved health outcomes. Although the HRH Program was designed to “build the health education infrastructure and health workforce necessary to create a high-quality, sustainable health care system in Rwanda” (MOH, 2011), the Statement of Task necessitates linking the Program’s aims to HIV-related outcomes at the population and patient levels. These outcomes reach further downstream than the stated goals and outcomes of the HRH Program.

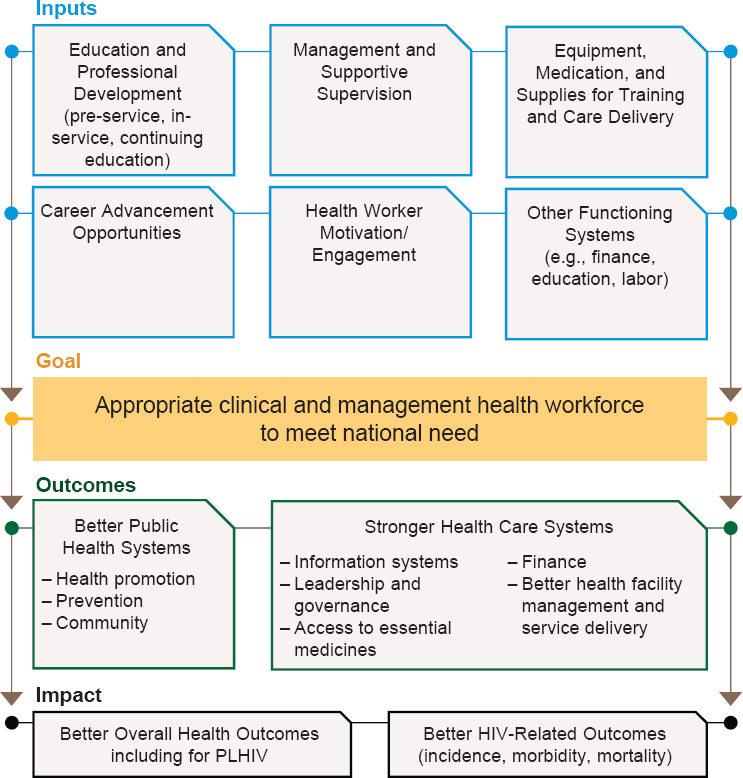

Developed through a combination of existing evidence, theory, and the expertise and knowledge of the study committee, the theoretical causal pathway (see Figure 1-2) strives to bridge the gap between the Program’s intentions and the evaluation’s objectives; it also guided the evaluation’s lines of inquiry and assessment of the contribution of PEPFAR-supported Program activities. The pathway is holistic, in that it includes elements that, although not funded under the HRH Program with PEPFAR support, are essential for building a health workforce that can effectively respond to the health needs of PLHIV. Taking this holistic view of HRH and associated needs to produce improved health outcomes for PLHIV facilitates examination of the context in which the Program was implemented.

As the causal pathway illustrates, a stronger health workforce that is able to meet the health needs of the population is understood, along with other factors, to generate improved public health and health care delivery systems. The combination of a functioning health system with an effective workforce results in better-quality services. This, in turn, contributes to improved health outcomes in general, including for PLHIV, and improved HIV-related outcomes, such as decreased incidence, mortality, and morbidity.

Key HRH outcomes, such as the number and density of health care workers, have been linked to important health services and population health outcomes. For example, lower physician density has been associated with higher maternal, infant, and under-5 mortality rates, and higher aggregate health care provider densities have been associated with higher immunization coverage and better health status (Anand and Bärnighausen, 2004; Robinson and Wharrad, 2001; Speybroeck et al., 2006). Other studies have found a negative relationship between physician density and morbidity more

NOTE: PLHIV = people living with HIV.

broadly, as measured by disability-adjusted life years (Castillo-Laborde, 2011). The WHO Task Force for Scaling Up Education and Training for Health Workers suggests that intermediate health outcome indicators related to direct contact with health care providers could be a useful way to measure health workforce scale-up (WHO and GHWA, 2008).

Although crucial for producing an effective health workforce, preservice and in-service health professional education alone are not sufficient. Health worker performance is also influenced by management and supportive supervision practices, professional development and promotion opportunities, salaries and other incentives, and functioning systems in the

health sector, such as referrals and supply chains (Bello et al., 2013; Henderson and Tulloch, 2008). Health workers’ engagement with their jobs is also associated with facility performance (Alhassan et al., 2013). For example, a recent study in Tanzania found that every 10 percent increase in health workers’ job satisfaction was associated with a 1 percentage point decline (95 percent confidence interval [CI]: 0.3–1.6) in HIV patients lost to follow-up (Lunsford et al., 2018).

It is widely recognized that a comprehensive health system is required to implement the interventions needed to decrease HIV-related mortality. However, it is also widely accepted that access to skilled HRH contributes to improved health outcomes and that insufficient HRH can exacerbate the impact of the HIV epidemic (McCoy et al., 2008). There can also be a bidirectional effect, in which investments in the response to HIV affect HRH, as evidenced by the effect, over time, of HIV funding from PEPFAR and the Global Fund on countries’ HRH strategies and policies (Cailhol et al., 2013).

Much of the literature addressing HRH and HIV focuses on task shifting and scale-up of ART services. Jaskiewicz and colleagues (2016) note a positive association between filled health care worker positions and greater provision of preventive services, such as testing and co-trimoxazole preventive therapy, which is commonly used to reduce HIV-related infections. Other studies have noted an association between staffing shortages and greater attrition for PLHIV (Govindasamy et al., 2012) and an association between greater staff burden for pharmacy staff—but not other facility staff—and greater risk of attrition for HIV patients (Lambdin et al., 2011).

Finally, although not illustrated in this theoretical causal pathway, it is important to note that many elements beyond the health sector influence the efficiency and effectiveness of the health system, both as a whole and in part. For example, without a functioning education sector that supports general education and professional educational institutions, students may not be prepared with the knowledge, skills, and competencies they need to be trained as health workers capable of providing high-quality care.

Assessment of Causality and Contribution to Impact

The third objective under the Statement of Task is to examine, “to the extent feasible, … the impact of PEPFAR funding for the HRH Program on HRH outcomes and patient- or population-level HIV-related outcomes.” The committee used the analytical approach of contribution to impact, the accepted standard, as an effective methodology for evaluating complex development assistance programs where an experimental design is not appropriate or feasible (IOM, 2014; Leeuw and Vaessen, 2009). Several factors complicated the feasibility and compromised the appropriateness of measuring a counterfactual and observing attributable impact: the retro-

spective nature of the evaluation, the timing of the evaluation with respect to the HRH Program’s plausible mechanisms of impact, the interacting effect of other factors and concurrent programs on the outcomes of interest, and the lack of an appropriate comparator.

The committee was charged to design, plan, and carry out this evaluation after the HRH Program had been implemented and after the end of the investment period being evaluated. This retrospective nature of the charge to the committee limited investigation into the causal impact of the Program on health outcomes for PLHIV, and especially on the population-level HIV incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality outcomes of interest named in the Statement of Task. When an understanding of causal impact is desired, the ideal design is prospective, with data collected from the beginning for either intervention and comparison groups or for a before-and-after comparison of the intervention group. This evaluation, by necessity, relied retrospectively on secondary indicator data that were not created or collected for evaluative purposes. As Chapter 2 details, a challenge for this evaluation was the availability of relevant measures to respond directly to requested aspects of the evaluation.

In addition, PEPFAR’s investments in the HRH Program and the subsequent request for this evaluation took place relatively recently, compared to the time frame required to develop and deploy highly qualified nurses and physicians. Effecting population-level change through investments in health professional education should be expected to take many years, if not decades, given the time required for training and for trainees to make their way as fully qualified health professionals into the service delivery system and as faculty to produce ongoing cohorts of providers. At the time of this evaluation, not enough time had elapsed to reasonably expect a sufficient volume of newly trained health providers to have been in the health system for long enough to observe changes in the population-level outcomes specified in the Statement of Task that could be attributed to the HRH Program.

Further complicating the ability to assess attributable impact was the difficulty of distinguishing the effects of HRH Program activities on the outcomes of interest from the effects of the multitude of other factors that contribute to HRH and HIV outcomes. The theoretical pathway presented above illustrates the range of these other factors. Programs that support and strengthen these other factors have an interactive effect. Concurrent with the HRH Program, there were investments from PEPFAR and other sources to support direct service delivery, quality improvement, capacity building, strengthening of other building blocks of the health system, and other interventions, all with the ultimate aim of affecting the same HIV-related outcomes. Population-level changes in health outcomes that could be used to reflect program impact cannot be separated by specific programs or investments. This makes it difficult to isolate and attribute improve-

ments to PEPFAR’s investments in the HRH Program. Even the impact on individual-level health measures is difficult to attribute, as the availability and quality of services an individual receives could be influenced by different programs, funded through different sources.

Another factor that ruled out an analysis of attributable impact was the lack of a comparator. Although it can be possible, in some cases, to employ a comparison design retrospectively, this was not an appropriate design in this case. Rwanda’s health and higher education systems—and the political, sociocultural, and historical context in which they operate—are key factors in the implementation of the HRH Program, just as with any other program. Rwanda’s unique context relative to other countries in Eastern and Southern Africa, the singularity of the University of Rwanda as the public-sector institution for health professional education in Rwanda, and the widespread deployment of the HRH Program’s trainees meant there was no appropriate comparison setting where the Program was not implemented that would allow attribution of outcomes.

This is made more complex by the HIV-related accomplishments in Rwanda before the start of the HRH Program. In 2012, when the Program was launched, HIV prevalence was 3.2 percent, with 52 percent ART coverage (UNAIDS, 2018b). In comparison to other countries in the region, these rates put Rwanda with the highest ART coverage and some of the lowest prevalence (see Table 1-1).

In 2016, Rwanda was the first country in the Eastern and Southern African regions to reach the “first 90” in the 90-90-90 target (90 percent of all PLHIV knowing their status by 2020). It reached the “second 90” goal of placing 90 percent of people who know their (HIV-positive) status on treatment in 2017 (UNAIDS, 2018c). The relatively high baseline for key HIV indicators in Rwanda meant any effects would be relatively small in magnitude. This made it particularly difficult to conduct a before-and-after

| Country | HIV Prevalence | ART Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| Uganda | 6.6% | 30% |

| Kenya | 5.6% | 41% |

| Tanzania | 4.9% | 33% |

| Rwanda | 3.2% | 52% |

| Burundi | 1.4% | 32% |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1.0% | 14% |

SOURCE: UNAIDS, 2018a.

comparison that could discern and isolate observable effects for a single program, focused on just one aspect of a health system in which multiple, interacting factors all play a role in access to high-quality care for PLHIV and have contributed to achievements in HIV-related outcomes both before and during PEPFAR’s investments in the HRH Program.

In light of these considerations, the committee used the lens of assessing contribution to impact in the context of the design and intent of the HRH Program and the landscape of other funding sources, other HIV programs, and other factors that affect health. Contribution analysis is an effective methodology in complex circumstances, where an experimental design or generating quantifiable measures of impact is not feasible or appropriate. In this approach, whether and how the elements of a theory of change led to the achievement of results are understood through concepts such as plausibility and reasonable agreement (Biggs et al., 2014; Mayne, 2011; Nakrošis, 2014).

Contribution analysis of this kind is accepted as an appropriate standard for large-scale development assistance programs because of their complexity (IOM, 2014; Leeuw and Vaessen, 2009), including specifically for PEPFAR. At a 2008 Institute of Medicine workshop on design considerations for evaluation of PEPFAR’s impact, participants described a need to “shift to a broader definition of impact evaluation and to a more nonlinear concept of causation” (IOM, 2008). As Patton (2012) notes, contribution analysis is particularly useful “where there are multiple projects and partners working toward the same outcomes, and where the ultimate impacts occur over long time periods influenced by several cumulative outputs and outcomes over time,” as is the case with HRH and HIV-related outcomes in Rwanda.

Contribution analysis approaches often begin with a theory of change, which is tested against evidence gathered throughout the evaluation (Mayne, 2012). The HRH Program had a framework that informed its design, but it did not have a theory of change that reflected external factors or that linked program activities with the outcomes of interest in the Statement of Task—HRH and individual- or population-level HIV outcomes. For this evaluation, the contribution analysis of the effects of the HRH Program was informed by the theory-based causal pathway, described above. This approach enabled the committee to reasonably examine, to the extent feasible, the effects of PEPFAR’s investment in the Program on HRH outcomes and on HIV-specific and other HIV-related health outcomes, including (1) the HRH Program’s potential to have made plausible contributions to improving mortality and morbidity outcomes for PLHIV in Rwanda during the time frame considered in this evaluation, and (2) its potential to improve future outcomes, as HRH outputs resulting from the Program are deployed over time in the health system.

USE OF THE EVALUATION

This evaluation provides a valuable opportunity to describe and understand how PEPFAR’s recent investment in building capacity for heath professional education in Rwanda, as part of efforts to address health workforce needs, contributed to HRH outcomes and to the health of PLHIV. Through a mixed-methods approach, guided by the theoretical causal pathway, the National Academies endeavored to respond to the request for this evaluation by conducting a rigorous assessment that took into account the complexities of the HRH Program and the Rwandan health system, the multitude of factors that contribute to health outcomes, and the challenges and limitations inherent in the timing and nature of the evaluation request.

By assessing convergence and consistency among findings from different yet complementary data sources and methods, and by exploring the data to understand areas of divergence, the committee was able to develop conclusions about the HRH Program’s performance and effects, and make recommendations to inform future HRH investments that support PLHIV and to advance PEPFAR’s mission. The committee’s hope is that the findings, conclusions, and recommendations generated from this evaluation and described in this report will be used by Rwandan, U.S., regional, and global stakeholders to inform future efforts to strengthen the health workforce in Rwanda and elsewhere.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized in eight chapters. Following this introduction and description of the evaluation’s scope and approach, Chapter 2 describes the evaluation design and methodology in more detail, followed by the findings and conclusions in Chapters 3 through 7. This includes content, corresponding to the committee’s Statement of Task, that describes PEPFAR’s investments in HRH over time; describes PEPFAR-supported HRH activities in Rwanda in relation to programmatic priorities, outputs, and outcomes; and examines the contribution of PEPFAR funding for the HRH Program to HRH outcomes and health outcomes, including HIV-related outcomes, in Rwanda. Chapter 3 examines the HRH Program’s vision and its design, which had implications for the activities and outcomes described in later chapters. Chapter 4 explores the individual twinning model the HRH Program used to build individual capacity of University of Rwanda faculty in teaching and clinical practice. Chapter 5 examines efforts to build institutional capacity at the University of Rwanda to continue producing high-quality health care workers. Chapter 6 presents data on the increased production of medical specialists, nurses, midwives, and administrators, as well as data on procurement of equipment and supplies

for medical education and training. In Chapter 7, the HRH Program’s contribution to health care service delivery and quality of care is discussed, along with a more detailed discussion of how impact could be assessed under circumstances different from those encountered in this evaluation. Chapter 8 captures the overall messages of the evaluation and conveys the recommendations the committee has made in response to its charge.

REFERENCES

Alhassan, R. K., N. Spieker, P. van Ostenberg, A. Ogink, E. Nketiah-Amponsah, and T. F. R. de Wit. 2013. Association between health worker motivation and healthcare quality efforts in Ghana. Human Resources for Health 11(1):37.

Anand, S., and T. Bärnighausen. 2004. Human resources and health outcomes: Cross-country econometric study. Lancet 364(9445):1603–1609.

Bello, D. A., Z. I. Hassan, T. O. Afolaranmi, Y. O. Tagurum, O. O. Chirdan, and A. I. Zoakah. 2013. Supportive supervision: An effective intervention in achieving high quality malaria case management at primary health care level in Jos, Nigeria. Annals of African Medicine 12(4):243–251.

Biggs, J. S., L. Farrell, G. Lawrence, and J. K. Johnson. 2014. A practical example of contribution analysis to a public health intervention. Evaluation 20(2):214–229.

Binagwaho, A., P. Kyamanywa, P. E. Farmer, T. Nuthulaganti, B. Umubyeyi, J. P. Nyemazi, S. D. Mugeni, A. Asiimwe, U. Ndagijimana, H. L. McPherson, J. D. D. Ngirabega, A. Sliney, A. Uwayezu, V. Rusanganwa, C. M. Wagner, C. T. Nutt, M. Eldon-Edington, C. Cancedda, I. C. Magaziner, and E. Goosby. 2013. The Human Resources for Health Program in Rwanda—A new partnership. New England Journal of Medicine 369(21):2054–2059.

Binagwaho, A., P. E. Farmer, S. Nsanzimana, C. Karema, M. Gasana, J. De Dieu Ngirabega, F. Ngabo, C. M. Wagner, C. T. Nutt, T. Nyatanyi, M. Gatera, Y. Kayiteshonga, C. Mugeni, P. Mugwaneza, J. Shema, P. Uwaliraye, E. Gaju, M. A. Muhimpundu, T. Dushime, F. Senyana, J. B. Mazarati, C. M. Gaju, L. Tuyisenge, V. Mutabazi, P. Kyamanywa, V. Rusanganwa, J. P. Nyemazi, A. Umutoni, I. Kankindi, C. Ntizimira, H. Ruton, N. Mugume, D. Nkunda, E. Ndenga, J. M. Mubiligi, J. B. Kakoma, E. Karita, C. Sekabaraga, E. Rusingiza, M. L. Rich, J. S. Mukherjee, J. Rhatigan, C. Cancedda, D. Bertrand-Farmer, G. Bukhman, S. N. Stulac, N. M. Tapela, C. Van Der Hoof Holstein, L. N. Shulman, A. Habinshuti, M. H. Bonds, M. S. Wilkes, C. Lu, M. C. Smith-Fawzi, J. D. Swain, M. P. Murphy, A. Ricks, V. B. Kerry, B. P. Bush, R. W. Siegler, C. S. Stern, A. Sliney, T. Nuthulaganti, I. Karangwa, E. Pegurri, O. Dahl, and P. C. Drobac. 2014. Rwanda 20 years on: Investing in life. Lancet 384(9940):371–375.

Cailhol, J., I. Craveiro, T. Madede, E. Makoa, T. Mathole, A. N. Parsons, L. Van Leemput, R. Biesma, R. Brugha, B. Chilundo, U. Lehmann, G. Dussault, W. Van Damme, and D. Sanders. 2013. Analysis of human resources for health strategies and policies in 5 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, in response to GFATM and PEPFAR-funded HIV-activities. Global Health 9(1):52.

Cancedda, C., R. Riviello, K. Wilson, K. W. Scott, M. Tuteja, J. R. Barrow, B. Hedt-Gauthier, G. Bukhman, J. Scott, D. Milner, G. Raviola, B. Weissman, S. Smith, T. Nuthulaganti, C. D. McClain, B. E. Bierer, P. E. Farmer, A. E. Becker, A. Binagwaho, J. Rhatigan, and D. E. Golan. 2017. Building workforce capacity abroad while strengthening global health programs at home: Participation of seven Harvard-affiliated institutions in a health professional training initiative in Rwanda. Academic Medicine 92(5):649–658.

Cancedda, C., P. Cotton, J. Shema, S. Rulisa, R. Riviello, L. V. Adams, P. E. Farmer, J. N. Kagwiza, P. Kyamanywa, D. Mukamana, C. Mumena, D. K. Tumusiime, L. Mukashyaka, E. Ndenga, T. Twagirumugabe, K. B. Mukara, V. Dusabejambo, T. D. Walker, E. Nkusi, L. Bazzett-Matabele, A. Butera, B. Rugwizangoga, J. C. Kabayiza, S. Kanyandekwe, L. Kalisa, F. Ntirenganya, J. Dixson, T. Rogo, N. McCall, M. Corden, R. Wong, M. Mukeshimana, A. Gatarayiha, E. K. Ntagungira, A. Yaman, J. Musabeyezu, A. Sliney, T. Nuthulaganti, M. Kernan, P. Okwi, J. Rhatigan, J. Barrow, K. Wilson, A. C. Levine, R. Reece, M. Koster, R. T. Moresky, J. E. O’Flaherty, P. E. Palumbo, R. Ginwalla, C. A. Binanay, N. Thielman, M. Relf, R. Wright, M. Hill, D. Chyun, R. T. Klar, L. L. McCreary, T. L. Hughes, M. Moen, V. Meeks, B. Barrows, M. E. Durieux, C. D. McClain, A. Bunts, F. J. Calland, B. Hedt-Gauthier, D. Milner, G. Raviola, S. E. Smith, M. Tuteja, U. Magriples, A. Rastegar, L. Arnold, I. Magaziner, and A. Binagwaho. 2018. Health professional training and capacity strengthening through international academic partnerships: The first five years of the Human Resources for Health Program in Rwanda. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 7(11):1024–1039.

Castillo-Laborde, C. 2011. Human resources for health and burden of disease: An econometric approach. Human Resources for Health 9(1):4.

Chen, L., T. Evans, S. Anand, J. I. Boufford, H. Brown, M. Chowdhury, M. Cueto, L. Dare, G. Dussault, G. Elzinga, E. Fee, D. Habte, P. Hanvoravongchai, M. Jacobs, C. Kurowski, S. Michael, A. Pablos-Mendez, N. Sewankambo, G. Solimano, B. Stilwell, A. de Waal, and S. Wibulpolprasert. 2004. Human resources for health: Overcoming the crisis. Lancet 364(9449):1984–1990.

Govindasamy, D., N. Ford, and K. Kranzer. 2012. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care: A systematic review. AIDS 26(16):2059–2067.

Henderson, L. N., and J. Tulloch. 2008. Incentives for retaining and motivating health workers in Pacific and Asian countries. Human Resources for Health 6(1):18.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2007. PEPFAR implementation: Progress and promise. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2008. Design considerations for evaluating the impact of PEPFAR: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2013. Evaluation of PEPFAR. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014. Evaluation design for complex global initiatives: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jaskiewicz, W., V. Oketcho, D. Settle, D. Frymus, F. Ntalazi, I. Ezati, and K. Tulenko. 2016. Investing in the health workforce to increase access to and use of HIV and AIDS services in Uganda. AIDS 30(13):N21–N25.

Lambdin, B. H., M. A. Micek, T. D. Koepsell, J. P. Hughes, K. Sherr, J. Pfeiffer, M. Karagianis, J. Lara, S. S. Gloyd, and A. Stergachis. 2011. Patient volume, human resource levels, and attrition from HIV treatment programs in central Mozambique. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 57(3):e33–e39.

Leeuw, F., and J. Vaessen. 2009. Impact evaluations and development: NONIE guidance on impact evaluation. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Lunsford, S. S., J. Kundy, X. J. Zhang, P. Magesa, and A. Nswila. 2018. Health worker engagement and facility performance in delivering HIV care in Tanzania. Journal of HIV and AIDS 4(1).

Mayne, J. 2011. Contribution analysis: Addressing cause and effect. In Evaluating the complex. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Mayne, J. 2012. Contribution analysis: Coming of age? Evaluation 18:270–280.

McCoy, D., B. McPake, and V. Mwapasa. 2008. The double burden of human resource and HIV crises: A case study of Malawi. Human Resources for Health 6(1):16.

McLaren, L., and P. Hawe. 2005. Ecological perspectives in health research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59(1):6–14.

MOH (Ministry of Health). 2011. Rwanda Human Resources for Health Program, 2011-2019: Funding proposal. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health.

MOH. 2014. Human Resources for Health monitoring & evaluation plan, March 2014. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health. (Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office [paro@nas.edu] or via https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08.)

MOH. 2016. Rwanda Human Resources for Health Program midterm review report (2012-2016). Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health. (Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office [paro@nas.edu] or via https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08.)

Moore, G., S. Audrey, M. Barker, L. Bond, C. Bonell, C. Cooper, W. Hardeman, L. Moore, A. O’Cathain, T. Tinati, D. Wight, and J. Baird. 2014. Process evaluation in complex public health intervention studies: The need for guidance. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 68(2):101–102.

Nakrošis, V. 2014. Theory-based evaluation of capacity-building interventions. Evaluation 20(1).

Ndenga, E., G. Uwizeye, D. R. Thomson, E. Uwitonze, J. Mubiligi, B. L. Hedt-Gauthier, M. Wilkes, and A. Binagwaho. 2016. Assessing the twinning model in the Rwandan Human Resources for Health Program: Goal setting, satisfaction and perceived skill transfer. Global Health 12(1).

Nsanzimana, S., K. Prabhu, H. McDermott, E. Karita, J. I. Forrest, P. Drobac, P. Farmer, E. J. Mills, and A. Binagwaho. 2015. Improving health outcomes through concurrent HIV program scale-up and health system development in Rwanda: 20 years of experience. BMC Medicine 13(1):216.

Open Data for Africa. 2018. Rwanda data portal: Health profile. Kigali, Rwanda: African Development Bank.

Palen, J., W. El-Sadr, A. Phoya, R. Imtiaz, R. Einterz, E. Quain, J. Blandford, P. Bouey, and A. Lion. 2012. PEPFAR, health system strengthening, and promoting sustainability and country ownership. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 60(Suppl 3):S113–S119.

Patton, M. 2008. Utilization-focused evaluation. 4th ed. Saint Paul, MN: Sage Publications.

Patton, M. Q. 2012. A utilization-focused approach to contribution analysis. Evaluation 18(3):364–377.

PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief). 2014. PEPFAR 3.0: Controlling the epidemic; delivering on the promise of an AIDS-free generation. Washington, DC: Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy.

PEPFAR. 2015. PEPFAR human resources for health: PEPFAR 3.0; February, 2015. Washington, DC: Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy.

PEPFAR Rwanda. 2015. Rwanda country operational plan (COP) 2015 strategic direction summary. Washington, DC: Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy.

Preskill, H., and T. T. Catsambas. 2006. Reframing evaluation through appreciative inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Robinson, J. J., and H. Wharrad. 2001. The relationship between attendance at birth and maternal mortality rates: An exploration of United Nations’ data sets including the ratios of physicians and nurses to population, GNP per capita and female literacy. Journal of Advanced Nursing 34(4):445–455.

Speybroeck, N., Y. Kinfu, M. Dal Poz, and D. Evans. 2006. Reassessing the relationship between human resources for health, intervention coverage and health outcomes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS). 2018a. AIDSinfo. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. aidsinfo.unaids.org (accessed August 31, 2019).

UNAIDS. 2018b. Country factsheets Rwanda 2018. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/rwanda (accessed February 5, 2020).

UNAIDS. 2018c. UNAIDS data 2018. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

Uwizeye, G., D. Mukamana, M. Relf, W. Rosa, M. J. Kim, P. Uwimana, H. Ewing, P. Munyiginya, R. Pyburn, N. Lubimbi, A. Collins, I. Soule, K. Burke, J. Niyokindi, and P. Moreland. 2018. Building nursing and midwifery capacity through Rwanda’s Human Resources for Health Program. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 29(2):192–201.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2006. The World Health Report 2006: Working together for health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2016. Health workforce requirements for universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO and GHWA (Global Health Workforce Alliance). 2008. Scaling up, saving lives: Task Force for Scaling Up Education and Training for Health Workers, Global Health Workforce Alliance. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

This page intentionally left blank.