2

Overview of Environmental Management Program Evolution

HOW THE PROGRAM CAME ABOUT

The mission of the earliest precursor agencies of the present-day U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) involved the use of atomic energy for defense purposes and then, with the passage of the McMahon Act in 1946, the use of atomic energy for civilian purposes as well. During the 1940s, wartime activities occurred at industrial scale on land reservations of hundreds of square miles in size. Smaller sites conducted upstream activities to fabricate materials needed at the larger sites for production of weapons grade materials (or for nuclear power fuel assemblies) and for the assembly of the weapons themselves. Interspersed within these sites and elsewhere in the larger complex were sites hosting research, development, and test operations also using atomic energy. In the following years, as peacetime activities involving atomic energy and other forms of energy and topics of research increased, and defense activities escalated, so too did the number of sites in the complex. The department’s inventory of sites for all its activities is now well over 150 (NASEM, 2017).

Several years after wartime activities ended, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) began considering the final disposition not only of the materials, the core of which were so-called “Atomic Energy Act materials,”1 but of the lands

___________________

1 These are defined in section 11 of the Atomic Energy Act (AEA) of 1954, as amended, as being of three types: source material, special nuclear material, and byproduct material. Source material is actinides, or ores containing actinides, that are fissionable with neutrons. Such ores can be milled and, when specified, selectively enriched in isotopes more suitable for nuclear chain reactions (becoming special nuclear material), and fabricated into fuel assemblies. The latter are used in the production of heavier elements or for release of fission energy to provide heat or generate mechanical or electric power (e.g., by raising steam to turn a Rankine cycle). Byproduct materials are chiefly those that

themselves at the dozen or so contract-operated laboratories and test ranges with significant land-holdings. The most radioactive of these wastes received the most attention, and by the late 1950s a consensus emerged that deep underground disposal in the lithosphere was the preferred method to isolate such wastes from the biosphere (NAS-NRC, 1957). Preparing and immobilizing wastes for ultimate disposition became the focus of further large-scale operations. In parallel, the issue of containing the wastes generated during the wartime activities became more urgent as natural processes conveyed radionuclide fractions outside site boundaries into environmental media and, within the sites, into soil and groundwater. The cleanup of environmental media2 thus became a significant mission area for the department.

By 1980, the responsibility for managing defense wastes had been assigned to DOE’s Office of Defense Programs pursuant to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1981. The annual budget for management of such wastes was approximately $300 million (Ghosling and Fehner, 1994, p. 29).

In 1989 DOE elevated and consolidated the responsibility for the cleanups within the organization. This created for the first time an assistant secretary with line management responsibility for the disposition of defense wastes.3 The organizational unit was called the Office of Environmental Restoration and Waste Management—albeit now headed by a presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed official—but within a few years became known as the Office of Environmental Management (EM).4

The Office of Environmental Management currently has three verticals: Field Operations (EM-3), Regulatory and Policy Affairs (EM-4), and Corporate Services (EM-5). This tri-partite structure followed from a reorganization in June 2016 that consolidated seven offices down to current three. Perhaps most prominently, this consolidation included “changes in the reporting relationships of the EM field organizations.”5 Whereas previously the headquarters units through

___________________

evolve during fission of source material and special nuclear material. Byproduct materials can also include mill tailings from the processing of source material; purified quantities of a particular isotope of the element radium; or material that has become radioactive in physics experiments involving highly-energetic particles. Interested readers should consult the AEA for definitions of the above having proper legal meaning and effect.

2 Collectively, “cleanup” may refer to soil and groundwater treatment, building demolition, disposal (often on-site), or waste processing and immobilization.

3 On November 8, 1981, Secretary of Energy James Watkins issued SEN-13-89 affirming the Department’s intention to ask for congressional authority for a new assistant secretary.

4 References to EM include both the Office of Environmental Management and the assistant secretary-level predecessor, the Office of Environmental Restoration and Waste Management.

5 Michele Inge-Farmer, Workforce Analytics & Planning Division, HC-52 Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer. June 30, 2016, “Memorandum for Mark Whitney, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary, Subject: Organization Change Implementation Material – Environmental Management.” H-14-16 (06/27/16).

which the sites reported were gathered under the assistant secretary (EM-1),6 they now reported to an associate principal deputy assistant secretary (EM-3).

REGULATORY REGIMES FOR WASTE MANAGEMENT

In the 1960s and 1970s, the department began to reckon with its major waste streams. A pilot project in New Mexico was proposed in a salt formation in the Permian Basin, and various wastes became candidates for final disposition there. A Defense Waste Processing Facility was proposed at the Savannah River Site (SRS) to immobilize the 25 million gallons of liquid waste in a form suitable for deep underground or “geologic” disposal. At the same time, the environmental laws that had been created in the years since the Atomic Energy Act led to debate over the applicability of these same laws to defense wastes.

Congress passed the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) in 1976, but, to a literal reading, the Act exempted sites with so-called mixed waste that has both AEA material and RCRA-hazardous constituents. The Department continued to assert for several years that the exemption of RCRA Section 1006 applied. Litigation followed, including a 1984 decision in which a federal court ordered DOE to comply with RCRA. See Legal Environmental Assistance Foundation v. Model, 586 F Supp. 1163 (E.D. Tenn. 1984).

Definitive resolution would have to wait until 1992 and the passage of the Federal Facilities Compliance Act (P.L. 102-386), which amended section 6001 of RCRA to specify that federal facilities are subject to “all civil and administrative penalties and fines, regardless of whether such penalties or fines are punitive or coercive in nature.”

The cleanup of inactive sites in the department’s inventory became subject to a further environmental law, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA or Superfund), created in 1980. The Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 required DOE to enter into cleanup agreements for all sites on the National Priorities List. CERCLA and RCRA are the two main laws under which EM cleanups proceed. (DOE, 2017).

While these legalities were being resolved, DOE in 1989 elevated and consolidated the responsibility for the cleanups within the department. This created for the first time an assistant secretary with line management responsibility for the disposition of defense wastes.7 EM was charged with the responsibility of cleaning up 107 contaminated sites in 35 states, covering approximately 3,100 square miles.8 Over time the on-site contractors funded by EM cleaned up sites

___________________

6 In addition, there is EM-2, the principal deputy assistant secretary.

7 Secretary of Energy James Watkins issued SEN-13-89 on November 8, 1981, affirming the Department’s intention to ask for congressional authority for a new assistant secretary.

8 Todd Shrader, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary (EM-2), Office of Environmental Management (EM), “EM Program History and Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

of varying size and complexity. (See the section “Accomplishments to Date,” below.) In 1989 four parcels at the Hanford Plant were added to the National Priorities List.9 By 1990, nine of the weapons complex sites were proposed or listed on the National Priorities List (OTA, 1991).

The authority to regulate radioactive material also shifted over time. In 1970, the newly created U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)10 was given authority set standards for radiation exposure and for the concentrations of Atomic Energy Act materials in the general environment. This authority was clarified in 1974 to allow EPA to specify such standards to apply outside the boundaries of sites without specificity on the particular activity occurring within.11 The AEC and its successors, the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA) and DOE, retained authority to regulate its own sites contaminated with AEA materials. There were exceptions to the latter; for example, the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant Land Withdrawal Act of 1993 (P.L. 102-579) gave EPA authority to set standards for that site, which EM developed and operates.

SIZE, SCOPE, AND SCALE OF EM PROGRAM

At its 1989 inception, EM was charged with the environmental cleanups of 107 sites in 35 states.12 The office set the priorities for cleanups in a 5-year plan issued in 1989 (Gosling and Fehner, p. 73). By one estimate, the 5-year plan contained over 1,500 projects (Gosling and Fehner, p. 77). The early years of EM were dominated by constructing and operating waste management facilities (over half of budget authority). Further significant outlays addressed corrective actions necessary to bring sites into compliance with the environmental laws and regulatory regimes noted above.

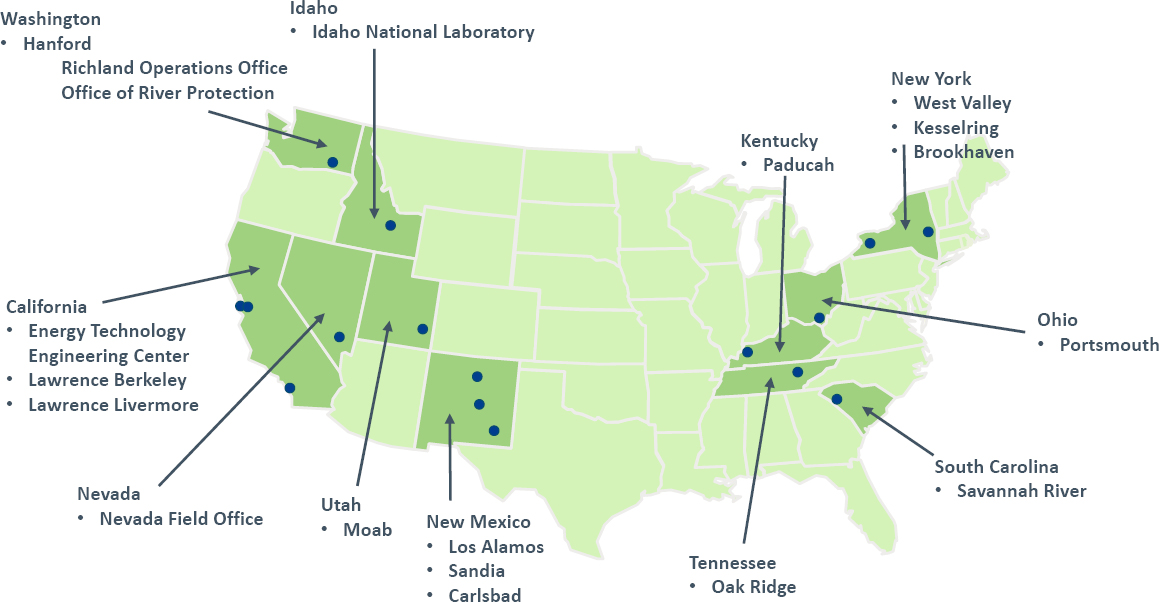

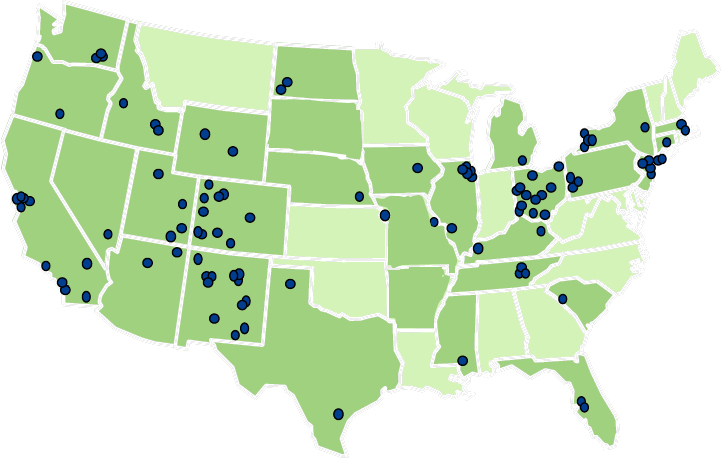

Today’s EM includes 17 sites (Figure 2.1), or a six-fold reduction versus 1989. Sixteen of these are contaminated from the use of atomic energy for defense purposes (see Table 2.1), the civilian nuclear fuel cycle, development of naval propulsion systems, or other Atomic Energy Commission objectives. A 17th site in Carlsbad, New Mexico, carries out disposal operations and accepts a specific type of waste (“transuranic”) contaminated with AEA material containing chiefly plutonium but also other actinides heavier than uranium.

Sites that are deemed sufficiently cleaned up are transferred to the Office of Legacy Management (LM). LM has responsibility for “long-term surveillance and maintenance, workforce restructuring and benefits, property management,

___________________

9 K. Schneider, 1989, “Agreement for a Cleanup at Nuclear Site,” The New York Times, February 28.

10 Reorganization Plan No. 3 of 1970. Federal Register 35: 15623; and 84 Stat. 2086.

11 R.D. Lyons, 1973, “E.P.A. Loses Power to Limit Radiation,” The New York Times, December 12.

12 Todd Shrader, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary (EM-2), Office of Environmental Management (EM), “EM Program History and Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

TABLE 2.1 List of Defense Sites

| Hanford Sitea |

| Idaho National Laboratory |

| Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory |

| Los Alamos National Laboratory |

| Nevada Nuclear Security Site |

| Oak Ridge |

| Sandia National Laboratory |

| Savannah River Site |

| Separations Process Research Unit |

| Waste Isolation Pilot Plant |

a Administered as two separate sites: the Office of River Protection and the Richland Operations Office.

SOURCE: DOE (2017).

land use planning, and community assistance.”13 LM continues the groundwater treatment activities from the EM ownership phase. For example, at the former Rocky Flats Plant in Colorado within the 1,300-acre Central Operable Unit, LM continues groundwater treatment and site monitoring. (The former security buffer zone, the Peripheral Operable Unit, was transferred in July 2007 to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge.14) Since its establishment in December 2003, LM has accepted the transfer of 101 sites.

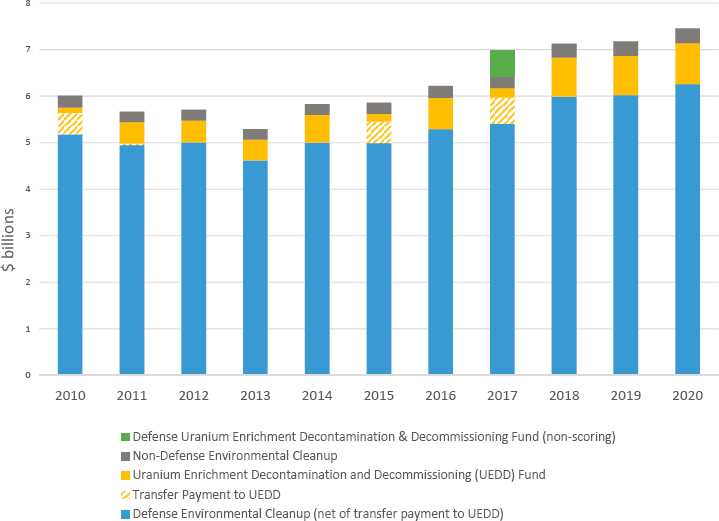

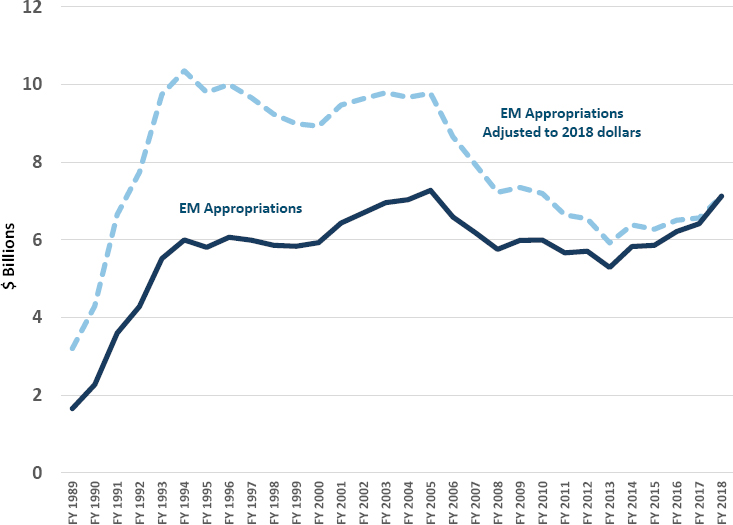

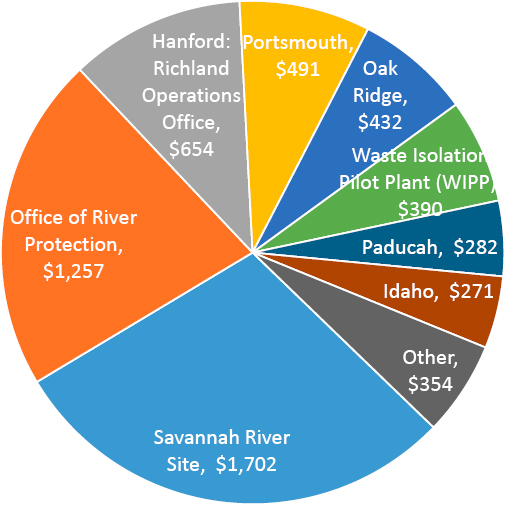

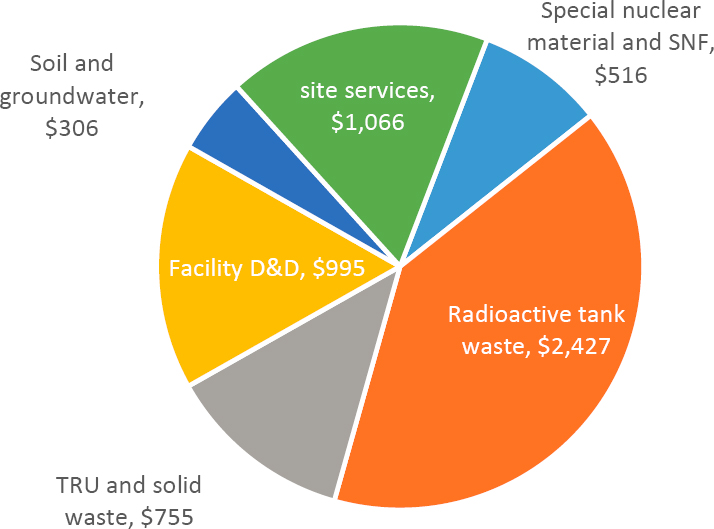

The budget authority for EM comes from more than one source, the dominant one being Atomic Energy Defense Activities, which is part of the National Defense Budget Function (050). Smaller portions of budget authority are sourced from the Non-Defense Environmental Cleanup account and the Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning account. These three accounts are allocated predominantly to the sites through headquarters and the monies obligated in contracts. The topline budget authority for the EM since its inception is shown in Figure 2.3. Figure 2.4 shows allocation to the eight largest sites in terms of budget authority. The budget priorities for FY 2021 are sorted by program breakdown structure (PBS) in Figure 2.5.

Recent accomplishments include, for example, the decontamination and decommissioning of the K-25 building at East Tennessee Technology Park (Oak Ridge National Laboratory), a gaseous diffusion plant; removal of sludge, debris and water from the K-West basin at the inactive K-West nuclear reactor in

___________________

13 U.S. Department of Energy “Office of Legacy Management,” https://www.energy.gov/lm/office-legacy-management.

14 Office of Legacy Management, 2020, “Fact Sheet: Rocky Flats Site, Colorado,” June, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/06/f75/RockyFlatsFactSheet.pdf.

Richland Operations Office (Hanford Site) in Washington state; and closure of almost 90 acres of coal ash and contaminated soil at the D-Area Ash Basin, adjacent to a steam and electricity plant that provided energy services at the Savannah River Site (Aiken, South Carolina).

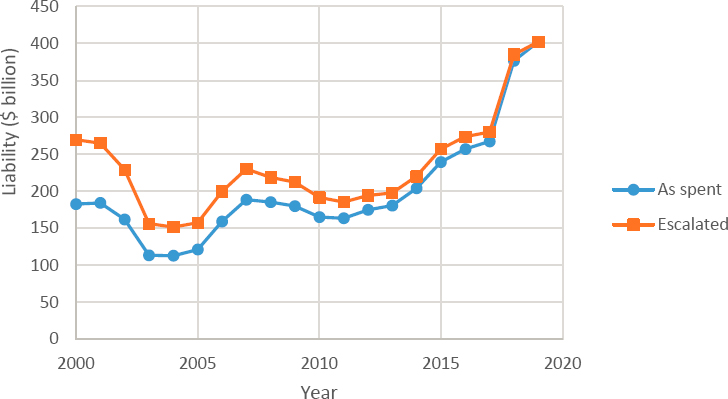

One measure of the size, scope, and scale of EM’s activities is the dollar amount of its cleanup liabilities. Environmental laws such as CERCLA and RCRA, noted above, require the cleanup of contaminated sites. These requirements and any specific remedies are negotiated with EPA and state authorities, and such remedies can be estimated and reported as liabilities. Since 2010 liabilities have increased $271 billion (see Figure 2.6). During the same time period, EM spent $70 billion on the sites. In recent years DOE has taken on additional contaminated sites from other DOE organizations (GAO, 2019, p. 7). The liabilities themselves have occasioned numerous studies by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).15

___________________

15 Amanda Kolling, Government Accountability Office, “DOE’s Environmental Cleanup Mission: Scope and Growth in DOE’s Environmental Liabilities and Challenges to Progress,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

ACCOMPLISHMENTS TO DATE

The cleanup of the industrial complex maintained by DOE and its predecessor agencies has proved to be a massive enterprise. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Manhattan Engineering District, started constructing the complex during the Second World War. The complex was expanded during the ensuing Cold War by the AEC, the Energy Research and Development Administration, and starting in 1977, DOE. At its peak, this nuclear complex encompassed 134 distinct sites in 31 states and 1 territory, with a total area of more than 2 million acres (DOE, 1998, Figure 2.7. Nuclear weapons and energy production activities required the construction of many buildings and facilities, produced large quantities of radioactive and hazardous wastes, and resulted in widespread groundwater and soil contamination at these sites, often referred to as “nuclear legacy sites.”

More than 100 of the DOE nuclear legacy sites required cleanup actions. Eleven were cleaned up prior to 1989; the majority of sites, 55, were cleaned up in the 10 years between 1989 and 1998; 20 sites were cleaned up between

1999 and 2008; and 5 sites between 2009 and 2019 (see Table 2.2).16 In total, EM and its predecessor offices have completed cleanup actions at 90 out of 107 sites.17 The remaining cleanup sites, listed in Table 2.3, are often cited as the most complex, and therefore the most costly to remediate with the longest timelines to completion.

To meet this objective, EM has undertaken a major cleanup effort, which, according to DOE, is the largest environmental cleanup in the world. Estimates of the remaining cost to cleanup have long been uncertain because the magnitude of contamination, the level of cleanup effort required at some sites, and the

___________________

16 Cleaned up refers to the state of the site in which cleanup actions were completed and the site determined “closed” by EM.

17 Todd Shrader, Principle Deputy Assistant Secretary (EM-2); Office of Environmental Management (EM), “EM Program History and Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

SOURCE: Adapted from Todd Shrader, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary (EM-2), Office of Environmental Management, “EM Program History and Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

environmental liability (one of the largest in the U.S. government) are still poorly understood (NRC, 2000, p. 14).

EM reports of continuing progress, as reported to the committee, include the following:18

- At Hanford’s Richland site, radioactive sludge has been transferred away from the Columbia River to T Plant.

- At Hanford’s other site, River Protection, significant steps were made in the ongoing construction of the Waste Treatment and Immobilization Plant required for processing the direct feed low activity waste.

___________________

18 The list of EM reports of continuing progress is adapted from Todd Shrader, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary (EM-2), Office of Environmental Management, “EM Program History and Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

TABLE 2.2 Department of Energy Office of Environmental Management’s Cleanup Completion of Sites

| Site | Closure Date |

|---|---|

| Hallam Nuclear Power Facility, NE | 1969 |

| Piqua Nuclear Power Facility, OH | 1969 |

| Bayo Canyon, NM | 1982 |

| Kellex/Pierpont, NJ | 1982 |

| University of California, CA | 1982 |

| Acid/Pueblo Canyons, NM | 1984 |

| Chupadera Mesa, NM | 1984 |

| Canonsburg, PA | 1986 |

| Shiprock, NM | 1987 |

| Middlesex Municipal Landfill, NJ | 1987 |

| Niagara Falls Storage Site Vicinity Properties, NY | 1987 |

| Salt Lake City, UT | 1989 |

| Spook, WY | 1989 |

| National Guard Armory, IL | 1989 |

| University of Chicago, IL | 1989 |

| Green River, UT | 1990 |

| Lakeview, OR | 1990 |

| Riverton, WY | 1990 |

| Tuba City, AZ | 1990 |

| Durango, CO | 1991 |

| Lowman, ID | 1992 |

| Pagano Salvage Yard, NM | 1992 |

| Elza Gate, TN | 1992 |

| Albany Research Center, OR | 1993 |

| Baker and Williams Warehouses, NY | 1993 |

| Falls City, TX | 1994 |

| Grand Junction Mill Tailings Site, CO | 1994 |

| Monument Valley, AZ | 1994 |

| Salton Sea Test Base, CA | 1994 |

| Project Chariot, AK | 1994 |

| Aliquippa Forge, PA | 1994 |

| Granite City Steel, IL | 1994 |

| Seymour Specialty Wire, CT | 1994 |

| Ambrosia Lake, NM | 1995 |

| Site | Closure Date |

|---|---|

| Holloman Air Force Base, NM | 1995 |

| Kauai Test Facility, HI | 1995 |

| Mexican Hat, UT | 1995 |

| Peak Oil PRP Participation, FL | 1995 |

| Alba Craft, OH | 1995 |

| Associate Aircraft, OH | 1995 |

| C. H. Schnoor, PA | 1995 |

| Chapman Valve, MA | 1995 |

| General Motors, MI | 1995 |

| Herring-Hall Marvin Safe Co., MA | 1995 |

| Gunnison, CO | 1995 |

| Oxnard Facility, CA | 1996 |

| South Valley Superfund Site, NM | 1996 |

| B&T Metals, OH | 1996 |

| Baker Brothers, OH | 1996 |

| Oak Ridge Associated Universities, TN | 1996 |

| Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, IL | 1996 |

| Site A/Plot M, IL | 1997 |

| Geothermal Test Facility, CA | 1997 |

| New Rifle, CO | 1997 |

| Old Rifle, CO | 1997 |

| Pinellas Plant, FL | 1997 |

| Slick Rock Old North Continent, CO | 1997 |

| Slick Rock Union Carbide, CO | 1997 |

| New Brunswick Site, NJ | 1997 |

| Ventron, MA | 1997 |

| Bellfield, ND | 1997 |

| Bowman, ND | 1998 |

| Maybell, CO | 1998 |

| Naturita, CO | 1998 |

| Center for Energy and Environmental Research, PR | 1998 |

| Ames Laboratory, IA | 1998 |

| Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, NJ | 1999 |

| Sandia National Laboratories – CA | 1999 |

| Monticello Remedial Action Project, UT | 1999 |

| Site | Closure Date |

|---|---|

| Columbus Environmental Management Project - King Avenue, OH | 2000 |

| Argonne National Laboratory - West, ID | 2000 |

| General Atomics, CA | 2001 |

| Grand Junction Office, CO | 2001 |

| Weldon Spring Site, MO | 2001 |

| Maxey Flats Disposal Site, KY | 2002 |

| Salmon Site, MS | 2005 |

| Laboratory for Energy-Related Health Research, CA | 2005 |

| Rocky Flats Environmental Technology Site, CO | 2006 |

| Kansas City Plant, MO | 2006 |

| Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory - Main Site, CA | 2006 |

| Amchitka Island, AK | 2007 |

| Columbus Environmental Management Project - West Jefferson, OH | 2007 |

| Ashtabula Environmental Management Project, OH | 2007 |

| Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, CA | 2007 |

| Fernald Environmental Management Project, OH | 2007 |

| Miamisburg Environmental Management Project, OH | 2008 |

| Pantex Plant, TX | 2009 |

| Argonne National Laboratory - East, IL | 2009 |

| General Electric Vallecitos Nuclear Center, CA | 2010 |

| Inhalation Toxicology Laboratory, NM | 2011 |

| Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, CA | 2014 |

SOURCE: Modified from Department of Energy, Office of Environmental Management, “Completed Cleanup Sites,” https://www.energy.gov/em/completed-cleanup-sites, accessed October 14, 2020.

- Cleanup of the East Tennessee Technology Park (ETTP) at Oak Ridge gained headway with completion of demolition of the K-1037 Building.

- The Savannah River Site completed an 11-year demonstration of two interim salt waste processing facilities, which support preparations for the startup of the Salt Waste Processing Facility, to be used to process tank waste on-site.

- The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) received its 12,500th shipment of transuranic waste for disposal.

- At the Idaho site, safely completed processing at the Advanced Mixed Waste Treatment Facility of stored transuranic waste, preparing it for offsite disposal;

TABLE 2.3 Department of Energy Sites and Locations with Current Remediation and Cleanup Activities; Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Budget Request Values Included

| Site Name | Location | FY 2021 Budget Request | End Datea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hanford: Office of River Protection | Richland, WA | $1.258 billion | |

| Hanford: Richland Operations Office | Richland, WA | $655 million | |

| Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory | Tracy, CA | $1.764 millionb | |

| Savannah River Site | Aiken, SC | $1.703 billion | |

| Portsmouth | Piketon, OH | $491 million | 2038 |

| Oak Ridge | Oak Ridge, TN | $432 million | |

| Paducah | Paducah, KY | $282 million | 2065 |

| Idaho | Idaho Falls, ID | $271 million | |

| Los Alamos National Laboratory | Los Alamos, NM | $120 million | |

| West Valley Demonstration Project | West Valley, NY | $92 million | |

| Nevada National Security Site | near Las Vegas, NV | $61 million | |

| Moab | Moab, UT | $48 million | |

| Separations Process Research Unit (SPRU) | Niskayuna, NY | $15 million | 2030 |

| Energy Technology Engineering Center (ETEC) | Canoga Park, CA | $11 million | |

| Sandia National Laboratories | Albuquerque, NM | $5 million | 2031 |

| Brookhaven National Laboratory | Upton, NY | $0 million | 2020 |

a As reported by EM’s 2020 strategic plan.

b Some EM-funded work is also managed by the National Nuclear Security Administration.

SOURCE: Modified from Department of Energy, Office of Environmental Management, “Cleanup Sites,” https://www.energy.gov/em/mission/cleanup-sites, accessed October 14, 2020.

- At Portsmouth, reached the highest operating uptime at the site’s depleted uranium hexafluoride conversion plant since it began operations; and

- At the West Valley site, completed disposition of waste from the demolition of the West Valley Demonstration Project vitrification plant, shipping nearly 460 containers of waste by train and truck to off-site disposal facilities.

These successes reported by EM do show progress at the remaining sites. However, as discussed above, the rate of increase of EM’s environmental liabilities eclipses the rate of closure of these sites and have increased $271 billion since 2010.

REFERENCES

DOE (U.S. Department of Energy). 1998. Paths to Closure: Accelerating Cleanup. DOE/EM-0362. June. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/631199-accelerating-cleanup-paths-closure.

______. 2017. Future-Years Defense Environmental Management Plan: FY 2018 to FY 2070. Washington, D.C.

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2019. Environmental Liabilities: DOE Would Benefit from Incorporating Risk-Informed Decision-Making into Its Cleanup Policy. GAO-19-339. Washington, D.C.

Gosling, F.S., and T.R. Fehner. 1994. Closing the Circle: The Department of Energy and Environmental Management: 1942 to 1994. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy. March.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Utilizing the Energy Resource Potential of DOE Lands. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

NAS-NRC (National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council). 1957. The Disposal of Radioactive Waste on Land. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10294.

NRC (National Research Council). 2000. Research Needs in Subsurface Science. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9793. Chapter 5.

______. 2007. Assessment of the Results of External Independent Reviews for U.S. Department of Energy Projects (2007). Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

OTA (Office of Technology Assessment). 1991. Complex Cleanup: The Environmental Legacy of Nuclear Weapons Production. OTA-O-484. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congress. February.