3

Contracting and Project Management in the Office of Environmental Management

CONTRACTING PRACTICES IN THE OFFICE OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT

The contracting model used by the Office of Environmental Management (EM) of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has evolved since its inception in 1989. Initially, management and operating (M&O) contracts prevailed, embodying a unique relationship between the government and contractor and a general work scope so as to comprehend the full suite of activities at a particular site, in some instances. These were cost-type contracts with fees paid either on a fixed fee schedule or incentive basis. Later EM employed contracts that had more specific work scope with cost reimbursement plus performance-based awards and fees.1 In the mid-1990s, DOE implemented several so-called closure contracts at the Rocky Flats Plant and the Fernald site, both chosen for accelerated closure by the Assistant Secretary for Environmental Management in 1996 (DOE, 2006, p. 3-23). These contracts were aimed at progressing the cleanup activities at the site toward a defined end state supported by fees and monetary incentives. The fees and awards were made following a set of award criteria in cost-plus-incentive fee (CPIF) contracts (DOE, 2020, p. 7), a type of cost reimbursement contract.

During the present study, EM explained that in the future large procurements will be subsumed under a new end-state contracting model (ESCM).2 The end state itself is described as follows:

___________________

1 Norbert Doyle, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Acquisition & Project Management (EM-5.2), “Contract Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

2 Written statement of Anne Marie White, Assistant Secretary for Environmental Management, before the Subcommittee on Strategic Forces Committee on Armed Services U.S.House of Representatives April 9, 2019, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/as/as29/20190409/109269/hhrg-116-as29-wstate-whitea-20190409.pdf.

Within the Performance Work Statement of the applicable contracts, the term “End State” is defined as the specified situation, including accomplishment of completion criteria, for an environmental cleanup activity at the end of the Task Order period of performance (POP).3

EM further explained the relationship between these end states and site completion: “End-state contracting is not a contract type but an approach to creating meaningful and visible progress through defined end-states, even at sites with completion dates far into the future. This is intended to create and motivate a culture of completion.” DOE envisages “a two-step process using a competitive qualifications-based Request for Proposal for selection of the offeror representing the best value and subsequent single source, Task Order(s) negotiations through effective partnering.” (DOE, 2020, p. 8) The first step results in a single-award indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ) contract to capture a substantial scope of work.4 The draw period of the IDIQ will be 10 years and uses a combination of firm fixed price (FFP) and cost reimbursement task orders. DOE sees the benefits of this end-state concept to include: quicker evaluations of proposals; less risk of protest loss; freeing up of contractor key personnel; and less proposal cost to industry.5

DOE has awarded two IDIQs under the ESCM at Hanford—the Central Plateau Cleanup Contract and the Tank Closure Contract—and one IDIQ for Nevada Environmental Program Services. Proposals for a fourth, the Integrated Management Cleanup Contract at the Savannah River Site, were accepted through December 1, 2020.6

PREVIOUS STUDIES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

The management of these projects has been the subject of study by different groups, and these studies led to specific changes at DOE. A rough chronology begins in 1998, when a series of reports by the National Research Council (NRC)

___________________

3 Rodney Lehman, EM-5.22, Department of Energy, “Responses to NAS Questions” sent to committee staff, June 30, 2020.

4 DOE described its “Principles of End State Contracting” to include the goal of having a very specific work-scope which potentially allows for a firm fixed price. DOE describes the benefits of this approach to include but not limited to: quicker evaluations of proposals; less risk of protest loss; frees up contractor key personnel; and less proposal cost to industry. (See Norbert Doyle, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Acquisition & Project Management (EM-5.2), “Contracting Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.)

5 Norbert Doyle, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Acquisition & Project Management (EM-5.2), “Contracting Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

6 American Nuclear Society, 2020, “Proposals Being Accepted for $21 Billion Savannah River Contract,” October 7, https://www.ans.org/news/article-2261/proposals-being-accepted-for-21-billionsavannah-river-contract.

were initiated by Congress. DOE subsequently worked to improve project management in three areas recommended by the NRC: “strengthening project management policies and guidance, developing consistent and objective performance information on ongoing projects, and improving the quality of federal oversight” (GAO, 2007a, p. 4). The Office of Engineering and Construction Management (OECM)7 (DOE, 1999) was formed within the Office of the Chief Financial Officer “to drive changes in DOE’s project management system and establish a strong project management capability” (NRC, 2007, p. 8); subsequently, DOE published Order 413.3, Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets on October 13, 2000.

The NRC reports continued annually and in 2004 found “inadequate planning, inadequate risk management, and inadequate monitoring and follow-up.” (NRC, 2004, p. 70). DOE issued the revised project management order, Order 413.3A on July 28, 2006 to incorporate lessons learned ((GAO, 2007b, p. 8) and in November 2010 issued the successor Order 413.3B, Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets (hereafter “Order 413.3B” or “the Order”). The DOE Office of Project Management, created in 2015, manages Order 413.3B and is the secretariat for the Energy Systems Acquisition Advisory Board (ESAAB) and the Project Management Risk Committee (PMRC).8

An internally led, externally advised study by DOE addressed project management as well. Initiated by a tasker memo from Secretary Steven Chu (March 31, 2011), this latter effort noted: “Appropriately constituted program offices with empowered program managers; strong line management with well understood roles and responsibilities; effective peer reviews; stability in organizational structure and personnel; and a culture of open information sharing could address many of EM’s program and project performance issues.”9

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found problems with DOE’s contract and project management and added the latter to its High-Risk Report first in 1990 where it has remained (GAO, 2019a). GAO further noted in 2019 that EM’s cleanup policy did not follow the majority of the leading practices for project management selected by GAO for evaluation (GAO, 2019b). The congressional request for the present study was made about this time.

The Department’s activities addressing project effectiveness and efficiency have evolved from the above activities and recommendations. EM applies Order 413.3B to those activities over $50 million in the following categories: major items of equipment (MIEs); environmental cleanup projects; and line-item construction projects. As of February 2020, there were 14 line-item construction

___________________

7 Congress had eliminated funding for the DOE office that was responsible for project and facilities management in 1999.

8 Office of Project Management, “About Us,” https://www.energy.gov/projectmanagement/about-us.

9 Daniel B. Poneman, Deputy Secretary of Energy, 2011, “Secretarial Review of Environmental Management Programs and Projects,” Washington, D.C., September 9.

projects and with a total project cost (TPC) of $21.6 billion, comprising roughly one-quarter of EM’s annual budget authority.10 The remaining three-quarters includes activities to which EM is not applying Order 413.3B. Some of these activities include site services while others include projects for decommissioning of buildings—a new protocol for these latter activities was published by EM in 2020—waste disposal operations, or environmental remediation.

The various studies discussed above are described in greater detail in Appendix C.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT AT DOE

The project management directive that applies to the work of EM is Order 413.3B, Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets. The earliest version was issued in 2000 following a period of concerted activity by DOE to address project management. The Deputy Secretary (S2)11 had, earlier that year, issued an interim instruction to serve as policy guidance on critical decisions by acquisition executives (AEs) and ESAAB and on the conduct of corporate level performance reviews. In June of 2000, DOE had issued Policy P413.1, which addressed project management accountability, the establishment of project management organizations, project management tools, and training of personnel. Order 413.3 followed from that policy.

In meetings with the committee, DOE described Order 413.3B as being “intended to provide the DOE Elements, including NNSA, with program and project management direction for the acquisition of capital assets with the goal of delivering projects within the original performance baseline (PB), cost and schedule, and fully capable of meeting mission performance unless impacted by a directed change.”12 It implements three directives from the U.S. Office of Management and Budget: A-11, Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget and the included Capital Programming guide; A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Internal Control; and A-131, Value Engineering. The applicability of Order 413.3B is to certain types of activities over $50 million TPC: construction projects, MIEs and environmental cleanup projects. It does not apply to information technology projects, weapons life extension projects, or financial assistance projects (cooperative agreements and grants).13

___________________

10 Norbert Doyle, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Acquisition & Project Management (EM-5.2), “Contracting Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

11 The Secretary has the designation “S1,” the Deputy Secretary “S2”, and the undersecretaries “S3”, “S4,” and “S5.”

12 Rodney Lehman, Director, EM Office of Project Management (EM-5.22), “Overview of DOE O[rder] 413.3B and EM Project Management Protocol for Demolition Projects,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

13 Paul Bosco, Director, Office of Project Management (PM), “Project Management (PM) Governance, Systems and Training,” presentation to the committee, May 6, 2020, Washington, D.C.

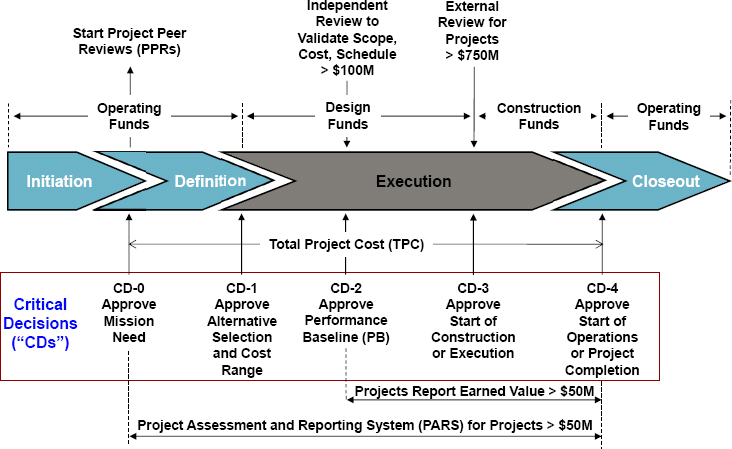

Order 413.3B contemplates several critical decision (CD) points as depicted in Figure 3.1. The official who can authorize each CD varies according to the total project cost (see Table 3.1).

There are a number of oversight committees internal to DOE including those concerned with project management:14

- Project Management Risk Committee (PMRC). PMRC is chaired by a noncareer senior advisor to the Deputy Secretary. (The Deputy Secretary is also Chief Executive (CE) for Project Management.) The director’s office of the Office of Project Management (PM-1) serves as executive secretariat. PMRC provides advice on cost, schedule, and technical issues regarding capital asset projects with a TPC of greater than $750M and on other high risk/high visibility projects, as needed.

- Energy Systems Acquisition Advisory Board (ESAAB). Chaired by the Deputy Secretary, ESAAB advises project management policy and issues, and assists the CE on each CD milestone (i.e., those of more than $750 million TPC).

In addition, the department operates a number of management information systems owned by the Office of Project Management (PM), which is a line office reporting to a different under secretary than EM. Two are most important for project management and oversight:15

- Project Assessment and Reporting System (PARS). Reporting on a monthly basis, PARS is DOE’s System of Record for project management information. PARS tracks projects with TPC greater than $50M, and PARS is the system that captures the progress reporting and documentation required per Order 413.3B to include: (1) At CD-0, Approve Mission Need: Start Narrative assessments/document upload; and (2) At CD-2, Approve Performance Baseline, to CD-4 (Completion): Start Cost and Schedule Data Reporting. Starting in June 2019, PARS was updated to include EMPOWER, a commercial off-the-shelf analysis and reporting tool to enable informed decision making.

- Earned Value Management System (EVMS) Project Control System. This control system implements the requirement of the Federal Acquisition Regulation to certify the use of an EVMS, which captures schedule, cost,

___________________

14 Adapted from Paul Bosco, Director, Office of Project Management (PM), “Project Management (PM) Governance, Systems and Training,” presentation to the committee, May 6, 2020, Washington, D.C.

15 Adapted from Paul Bosco, Director, Office of Project Management (PM), “Project Management (PM) Governance, Systems and Training,” presentation to the committee, May 6, 2020, Washington, D.C.

TABLE 3.1 Decision Authority for Various Levels of Total Project Cost (TPC)

| Critical Decision Authority | Total Project Cost Thresholds |

|---|---|

| Deputy Secretary | ≥ $750 million |

| Under Secretary | ≥ $100 million and < $750 million |

| Program Secretarial Officer | > $50 million and < $100 million |

SOURCE: Paul Bosco, Director, Office of Project Management (PM), “Project Management (PM) Governance, Systems and Training,” presentation to the committee, May 6, 2020, Washington, D.C.

and technical performance data to be used for informed decision making. The corporate ownership of this control system is with PM.

This chapter has described DOE’s process and controls for project management. Crucially, the above are applied according to threshold criteria and to certain types of projects as described in the applicability of Order 413.3B. The committee has received briefings and exchanged written queries and replies with DOE to understand these processes and controls as used in EM for the defense nuclear waste cleanups. The following chapters analyze these in more detail and offer findings and recommendations.

REFERENCES

DOE (U.S. Department of Energy). 1999. Memorandum for All Departments from T.J. Glauthier, Deputy Secretary. Subject: Project Management Reform Initiative. June 25.

______. 2006. Closure Legacy: From Weapons to Wildlife. Rocky Flats Project Office. Washington, D.C. August.

______. 2020. Department of Energy FY 2021 Congressional Budget Request: Volume 5, Environmental Management. DOE/CF-0166. Washington, D.C.

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2007a. Report to the Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development, Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives. https://www.gao.gov/assets/270/260444.pdf.

______. 2007b. Department of Energy: Consistent Application of Requirements Needed to Improve Project Management. GAO 07-518. Washington, D.C.

______. 2019a. High-Risk Series: Substantial Efforts Needed to Achieve Greater Progress on High-Risk Areas. GAO 19-157SP. Washington, D.C.

______. 2019b. Nuclear Waste Cleanup: DOE Could Improve Program and Project Management by Better Classifying Work and Following Leading Practices. GAO-19-223. Washington, D.C.

NRC (National Research Council). 2004. Progress in Improving Project Management at the Department of Energy: 2003 Assessment. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

______. 2007. Assessment of the Results of External Independent Reviews for U.S. Department of Energy Projects. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.