6

Contract Structures

RATIONALE FOR COMPLETION-ORIENTED CONTRACTING

A review of the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2019 (DOE, 2019) highlights the continued growth in environmental cleanup and disposal liabilities, rising from $377 billion in 2018 to $402 billion (not including future inflation). In 2015, the Office of Environmental Management’s (EM’s) liability was only $240 billion. Changes in technical approach, scope, regulations, laws, and inflation adjustments drove this growth.

In its management analysis, DOE has identified important ongoing efforts, including “defining requirements in measurable outcomes” and “using objective performance measures focusing on outcomes to balance considerations of cost control, schedule achievement, and technical performance.” Specifically, continued performance initiatives include:

- Incorporating the concept of end-state contracting in major contracts and procurements to reinvigorate the sense of urgency and the completion mindset:

- Building on successes of past initiatives, such as the accelerated closure of the Rocky Flats Plant1 in Colorado, to include a well-defined work scope with specific end states aimed at limiting increases to liabilities at EM sites;

___________________

1 Once it became no longer operational, the plant was known by other names such as “Rocky Flats Environmental Technology Site.”

- Demanding strong performance from contractors to make meaningful, discrete, and tangible progress in accomplishing EM’s important cleanup mission;

- Driving down operating and maintenance costs at EM’s facilities, which are a significant portion of EM’s annual budget, to provide more available funding to complete cleanup work; and

- Changing the culture to refocus on the completion of cleanup activities; linking contract objectives to DOE’s overall strategic goals.

The committee concurs with the imperative of outcomes-based completion contracting and agrees with the need to build on past successful initiatives such as the accelerated closure of the Rocky Flats Plant and the Feed Materials Production Center2 (known as the Fernald site) in Ohio. (Both the Rocky Flats Plant and the Fernald site had been chosen for accelerated closure by the Assistant Secretary for Environmental Management in 1996 [DOE, 2006, p. 3-23]. The closure contract issued in 2000 for Rocky Flats Plant was somewhat exceptional, being granted a sole-source justification by Secretary Richardson and a 30-day congressional review period [DOE, 2006, p. 4-9].) Outcomes-based, completion-oriented contracting allows the intent of a DOE program strategy to be fully integrated into the cleanup enterprise. An outcomes-based contracting approach:

- Focuses on reducing the cleanup footprint (i.e., the number of acres requiring remediation), an approach which reduces associated overhead costs and life-cycle costs;

- Reduces the risk of contractors focusing on narrowly defined performance criteria associated with performance-based incentive contracts; establishes results-oriented outcomes measures with incentives tied to completion;

- Reduces risks associated with incomplete statements of work for highly complex work activities to support fixed-price contracts;

- Ensures that white space risks (i.e., the risks of gaps between the scopes of work of contracts or task orders) are transferred in a broader outcome-based completion contract; and

- Fosters incentive driven innovations in outcomes focused on project execution, as seen in the reduction of expected cleanup time at Rocky Flats Plant and the Fernald site.

___________________

2 Once it became no longer operational, it was known as the “Fernald Environmental Management Project.”

DESCRIPTION OF CURRENT PLANS FOR USING IDIQ MODEL AS BASIS FOR COMPLETION CONTRACTS

EM has started implementing a redefined end-state contracting model (ESCM) approach.3 An end state in this new construct is described as follows:

Within the Performance Work Statement of the applicable contracts, the term “end state” is defined as the specified situation, including accomplishment of completion criteria, for an environmental cleanup activity at the end of the Task Order period of performance (POP).4

Emphasizing the manner in which the end-states achieved contribute to site completion, EM has described ESCM as follows: “End-state contracting is not a contract type but an approach to creating meaningful and visible progress through defined end states, even at sites with completion dates far into the future. This is intended to create and motivate a culture of completion.” DOE envisages “a two-step process using a competitive qualifications-based Request for Proposal for selection of the offeror representing the best value and subsequent single source, Task Order(s) negotiations through effective partnering” (DOE, 2020, p. 8). The first step results in a single-award indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ) contract to capture a substantial scope of work.5 The draw period of the IDIQ will be 10 years and uses a combination of firm fixed price (FFP) and cost reimbursement task orders.

DOE awarded two IDIQs under the ESCM at Hanford—the Central Plateau Cleanup Contract and the Tank Closure Contract—and one IDIQ for Nevada Environmental Program Services. Proposals for a fourth, the Integrated Management Cleanup Contract at the Savannah River Site, were accepted through December 1, 2020.6

The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) expresses a preference for multiple contract awards unless exceptions are met (see Chapter 7). Multiple award

___________________

3 Anne Marie White Assistant Secretary for Environmental Management, Written Statement Before the Subcommittee on Strategic Forces Committee on Armed Services United States House of Representatives April 9, 2019. Available at https://docs.house.gov/meetings/as/as29/20190409/109269/hhrg-116-as29-wstate-whitea-20190409.pdf.

4 Rodney Lehman, Department of Energy (DOE), EM-5.22, “Responses to NAS Questions” sent to committee staff June 30, 2020.

5 DOE described its “Principles of End State Contracting” to include the goal of having a very specific work-scope which potentially allows for a firm fixed price. DOE describes the benefits of this approach to include but not limited to: quicker evaluations of proposals; less risk of protest loss; frees up contractor key personnel; and less proposal cost to industry. Information from Norbert Doyle, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Acquisition & Project Management (EM-5.2), “Contracting Overview,” presentation to the committee, February 24, 2020, Washington, D.C.

6 American Nuclear Society, 2020, “Proposals Being Accepted for $21 Billion Savannah River Contract,” October 7, https://www.ans.org/news/article-2261/proposals-being-accepted-for-21-billionsavannah-river-contract/.

contracts are traditional IDIQ acquisition strategies, and the committee did not learn of how EM’s choice of a single-award IDIQ is complying with FAR 16.504(c)(1) or how it documents the use of the exceptions.

EM views ESCM as enabling “success similar to that experienced at the Rocky Flats, Mound7 and Fernald Sites.”8 A comparison of various contracting approach attributes follows for the Fernald site, the Rocky Flats Plant, and the ESCM in Table 6.1. The rows in the table describe elements of the contract. Reading across these rows, the reader can see the differences in approach including for example the streamlined regulatory process, the use of innovation, and the strong partnering, some or all of which were noteworthy at Fernald and Rocky Flats.

ANALYSIS OF PAST CASE STUDIES OF COMPLETION CONTRACT MODELS

Two of EM’s cleanup efforts that are often cited as successes in achieving program objectives at low cost and accelerated schedule were the aforementioned Rocky Flats Plant in Colorado and the Feed Materials Production Center (Fernald site) in Ohio. The Project Management Institute recognized both as a Project of the Year (Rocky Flats in 2006; Fernald in 2007). The Fernald Preserve, Ohio, Site, as it is called today, is managed by the DOE’s Office of Legacy Management (LM), which carries out ongoing groundwater cleanup and other site monitoring and remediation activities and monitors the on-site disposal facility.9 Today’s Rocky Flats Site is also managed by LM and carries out continued groundwater treatment and site monitoring on a 1,300-acre Central Operable Unit. The former security buffer zone of Rocky Flats, the Peripheral Operable Unit, was transferred in July 2007 to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge.10 Both the Rocky Flats Plant and the Fernald site had, as noted, been chosen for accelerated closure in 1996 (DOE, 2006, p. 3-23).

This section describes the program and contract approaches that contributed to the programs’ success. An important takeaway is the contracts for the Fernald site and Rocky Flats Plant employed approaches that allowed DOE to overcome the initial poorly defined costs, schedule estimates, and technical approaches. The lessons learned from this experience have informed the recommendations at the end of the chapter.

___________________

7 The site in Mound, Ohio, fulfilled diverse mission requirements related to nuclear weapons, space missions and energy research and development. After operations ceased in 2003, it was cleaned up to an end state that could support industrial and commercial uses and was assigned to the Office of Legacy Management.

8 DOE, Office of Environmental Management (EM), “Acquisition,” https://www.energy.gov/em/services/program-management/acquisition.

9 DOE, Office of Legacy Management, 2020, “Fact Sheet: Fernald Preserve, Ohio, Site,” May, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/05/f75/FernaldPreserveFactSheet.pdf.

10 DOE, Office of Legacy Management, 2020, “Fact Sheet: Rocky Flats Site, Colorado,” June, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/06/f75/RockyFlatsFactSheet.pdf.

TABLE 6.1 Comparison of Contracting Approaches Used by the Department of Energy (DOE)

| Contract Attribute | Fernald | Rocky Flats | End-State Contracting Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total closure cost ($B) | $4.40 | $10.00 | |

| Original closure estimate (years) | 27 | 65 | |

| Actual closure (years) | 15 (1992-2006) | 11 (1995-2005) | |

| Closure time savings (years) | 12 | 44 | |

| Original Closure Estimate ($B) | $12.20 | $37.0 | |

| Closure cost savings ($B) | $7.80 | $27.00 | |

| Closure contract value ($B) | $2.40 | $4.86 | |

| Closure contract start date | 12/2000 | 1/2000 | |

| Closure contract end date | 12/2006 | 12/2006 | |

| Actual completion | 10/2006 | 10/2005 | |

| Authorization/funding | Levelized funding; unique funding flexibility approach | All closure work authorized at contract signing | Task-order driven |

| Contract completion and transition document | Yes | No | No |

| Nature of relationship | Strong partnering focus | Strong partnering focus | Transactional approach limits partnering benefits |

| When end state defined to contractor (definition/scope of end state and date) | Pre-award | Pre-award | Post-award |

| Approach to achieving end state | Contractor | Contractor | DOE via task orders |

| Ownership of white space risk between defined projects to accomplish closure | Contractor | Contractor | DOE |

| Incentives | Outcomes (closure) based | Outcomes (closure) based | Output based task by task |

| Contractor performance focus | Overall closure | Overall closure | Task-based performance focus |

| Nature of contractor improvement focus | Contract (closure) | Contract (closure) | Task order (with emphasis on FFP tasks) |

| Focus on innovation and continuous process improvement | High | High | Limited opportunity to capture benefits |

| Contract Attribute | Fernald | Rocky Flats | End-State Contracting Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOE project oversight responsibilities | Focused on managing the contract not the contractor | Focused on managing the contract not the contractor | Tasks each require DOE oversight |

| Contract management | Strategic (outcomes focus) | Strategic (outcomes focus) | Tactical (task focus) |

| Cost control | Opportunity for DOE savings | Opportunity for DOE savings | Little incentive for contractor to control costs. |

| Land use end state—Wildlife refuge (acres) | 950 | 4,883 | |

| Land use end state—Other (acres; approximate) | 100 | 1,617 | |

| Regulatory approach | Traditional | Streamlined | Unknown |

Fernald

The original cost to complete the cleanup of Fernald had been estimated to be $12 billion and to take until 2025.11 By 1996, this completion date had been revised to 2010 (GAO, 1997). Final cleanup costs totaled $4.4 billion when completed in 2006, a reduction of nearly $8 billion versus the original estimate. EM initially expected a cost-plus incentive fee closure contract to complete in December 2009, but were able to execute the project with a revised completion date of December 2006, completed over a month early and under the contract’s target cost. EM and its contractor (Fluor) were able to close and restore portions of the site to its native habitat in 2006.

The shared focus of Fluor and EM on closure and program structure flexibility while addressing the inevitable contingencies that arise on large, complex projects led to innovative project execution in all dimensions, including:

- Developing and implementing an end-state closure plan;

- Challenging all costs through the implementation of an “austerity program”;

- Reducing indirect costs from 45 to 15 percent, saving $600 million in this category alone

___________________

11 C. Maag, 2006, “Nuclear Site Nears End of Its Conversion to a Park,” New York Times, September 20.

- Developing and maintaining a set of execution-ready projects to work around any delays experienced in planned project execution activities and position to take advantage of any additional funding that might become available; and

- Utilizing a unique funding flexibility approach that allowed deferral of provisional fees to maintain or accelerate overall closure schedule.

The projects to achieve closure and the programs to support and provide oversight of the projects were within the incentivized contractor’s control. In large part, success resulted from the significant culture change driven by the contractor’s project integration management strategy and powerful focus on safety.

Negotiated about 6 months after that of the Rocky Flats Plant, the contract for Fernald required development of a contract completion and transition document, which improved on the Rocky Flats contract (DOE, 2006, p. 4-14).

Rocky Flats

A report by EM initially predicted that site closure would take approximately 65 years and more than $37 billion in cleanup costs for the Rocky Flats Plant (DOE, 1995). DOE, the contractor (Kaiser-Hill Co.), and the state of Colorado worked together to develop a cooperative cleanup agreement and a streamlined regulatory process.12 Using a performance- and incentive-based contract, the site team set an aggressive target closure date of 2006. The work was completed a year early (and 50 years earlier than initially predicted) and $7.4 billion under budget (and over $20 billion less than original estimates).

Four key factors contributed to the early completion of the physical cleanup of Rocky Flats:

- The cost-plus-incentive-fee contract provided the contractor with strong profit incentives to complete the work quickly and safely (DOE, 2020, p. 7). These profit incentives drove site workers to look for innovative and creative cleanup solutions because they could receive bonuses for cost-saving suggestions. The incentives also led to a continuing focus on safety, as one significant safety infraction could shut down work in a building or throughout the site. DOE offered the contractor $560 million in total incentive fees to finish the cleanup ahead of schedule and under cost.

___________________

12 The State of Colorado, U.S Environmental Protection Agency Region VIII, and U.S. Department of Energy, 1996, “Rocky Flats Cleanup Agreement: Federal Facility Agreement and Consent Order,” CERCLA VIII-96-21, RCRA (3008(h)) VIII-96-01, and State of Colorado Docket # 96-07-19-01, July 19.

- DOE and the contractor overcame several major challenges through innovation, as workers constantly sought ways to complete their tasks quickly and under budget. Resolution of the question of expected future use led to resolution of the uncertainty about what cleanup levels were appropriate.13 In the mid-1990s, DOE, EM, the contractors, and Colorado collaborated with the community and regulatory agencies to resolve this uncertainty and determine a suitable end state (Rocky Flats FSUWG, 1995). A further challenge that has proved to be an obstacle to completion of other sites—namely, finding a path to disposal for the numerous waste types—was overcome at Rocky Flats (DOE, 2006, p. 5-7).

- DOE and the site’s regulatory agencies agreed to use an accelerated process to clean up the site. EPA’s Superfund accelerated cleanup process allowed cleanup actions to proceed much more quickly and collaboratively than they would have under the traditional Superfund process. As the cleanup progressed, DOE, the contractor, EPA, and state staff often worked side by side in the field.

- Several site-specific characteristics combined to limit the scope and complexity of the cleanup effort. Site-specific characteristics (e.g., climate, geography, the robust construction of the buildings, and the chemical nature of the key contaminants) physically limited the extent of the contamination. For example, the dry Colorado climate and the alluvial fan on which the site is situated helped minimize erosion, thereby inhibiting off-site migration of contaminants. Also, the thick shale and claystone that underlie the site prevented contaminants from seeping into the deep drinking-water aquifer.

Authorization of all project completion work when EM executed the contract moved the project from an annual planning cycle to one with a project completion focus. The closure contract included simplified terms and conditions supporting accelerated, efficient, and cost-effective project execution. DOE approval thresholds were high for any work sequence or process changes. DOE-directed changes automatically resulted in requests for equitable adjustment acting to check such requests.

The project’s final evolution to simplified, objective performance measures focused on overall site closure led to a consensus on the “critical few” performance measures and, eventually, end-state criteria. A cost-plus-incentive fee (CPIF) contract such as the one used at the Rocky Flats Plant may need to be adjusted if incentives no longer function as intended in the contract.

___________________

13 See, for example, DOE EM, 2003, “DOE P 455.1, Use of Risk-Based End States,” https://www.directives.doe.gov/directives-documents/400-series/0455.1-APolicy July 15.

IDENTIFICATION AND DISCUSSION OF OPTIONS FOR MOVING TOWARD COMPLETION CONTRACTS

EM has recognized that creating a culture of completion is important to its mission success14 and that creating a culture of completion led to the successes at Fernald and Rocky Flats.

The work at the Fernald site and Rocky Flats Plant relied on a strong definition of end states—defined in then-contemporary DOE policy documents as “representations of site conditions and associated information that reflect the planned future use of the property”15—and overall used a different approach than currently planned and practiced in the EM cleanup program. An end state is not solely a contracting method but must be subsumed under programmatic goals for individual sites.

Applying lessons learned from the Rocky Flats Plant and Fernald site will necessitate defining interim end states moving to ultimate closure. Strong definition supported by program strategies and plans will open the door for more appropriate contracting strategies, such as those used at Fernald and Rocky Flats. It will focus EM on managing the contract and not the contractor, undertaking a more strategic, governance role focused on partnership for success.

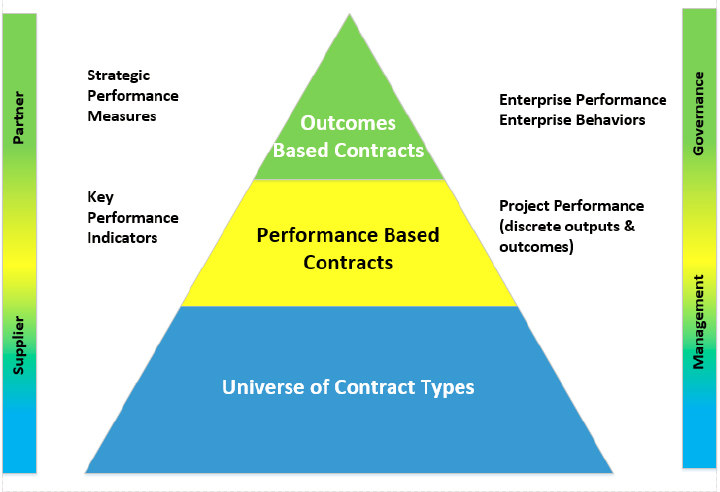

How Different Contract Types Are Intended to Work

There are many ways to look at the potential range of contract types. First, however, it is useful to look at the behaviors that contracts seek to drive. The broad universe of contract types includes various types of input and output contracts procured through various contract forms. A subset of these are performance-based contracts, which focus on delivering specific project-based outputs. Finally, a further subset of these contracts are outcomes-based contracts, focused on enterprise-level outcomes such as completion or closure: see Figure 6.1. The Fernald and Rocky Flats contracts were very much in this category.

The new ESCM and IDIQ contracting approach is limited to achieving project-based outputs. It relieves EM of defining end states at the time of procurement.

The four common types of government contracts available to EM include:

- Fixed-price contracts—used when contract risks are defined within acceptable limits. Such contracts require “delivery of a product or services

___________________

14 Anne Marie White Assistant Secretary for Environmental Management, Written Statement before the Subcommittee on Strategic Forces Committee on Armed Services United States House of Representatives April 9, 2019. Available at https://docs.house.gov/meetings/as/as29/20190409/109269/hhrg-116-as29-wstate-whitea-20190409.pdf.

15 See, for example, DOE EM, 2004, “DOE P 455.1, Use of Risk-Based End States,” https://www.directives.doe.gov/directives-documents/400-series/0455.1-APolicy, July 15.

- FFP contract

- FFP level-of-effort term contract

- FFP materials reimbursement type contract

- Fixed-price contract with award fees

- Fixed-price contract with economic price adjustment

- Fixed-price incentive (FPI) contract

- Fixed-price with prospective price redetermination

- Fixed-ceiling-price with retroactive price redetermination contracts

- Cost-reimbursement and cost-plus contracts—used when uncertainties involved in contract performance do not permit fixed-price contracts to be used; used when long-term quality is of higher concern than cost; cost-plus incentive contracts provide reimbursement for costs to budgeted authorization and other incentives to the contractor, reducing government risks.

- Cost contracts

- Cost-plus-fixed-fee (CPFF) contracts

- Cost-plus incentive contracts

- Cost-plus-incentive fee (CPIF) contracts—this form of contract was used by Fernald and Rocky Flats

- Cost-plus-award-fee (CPAF) contracts

at a specified price, fixed at the time of contract award and not subject to any adjustment” (DOE, 2008).

- Cost-sharing contracts

- Time-and-material (T&M) contracts—highest risk to government, lowest risk to contractor

- Indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ) contracts—can be used on both a fixed-price and cost-reimbursement basis; streamlines contracting process; often are multi-award contracts

- Task-order contracts (TOCs) and job-order contracts (JOC)

- Advisory and assistance (A&A) services

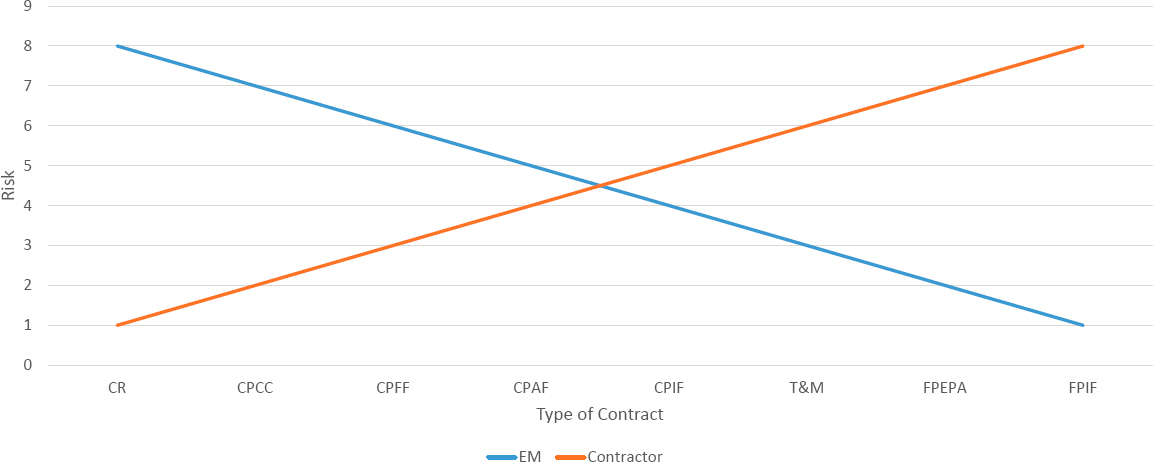

Figure 6.2 illustrates the relative risk to EM and a contractor under different forms of contracts.

As contractor risk increases, so too does its required risk contingency and profit margin. Lowering EM risk by shifting its responsibility to the contractor is not always a desired outcome. The private sector’s limited tolerance for risk often demands excessive contingencies and margins. Where EM has difficulty defining the requirements for an end-state, shorter cost-based contracts are its best choice. Where end states and the risks are well known and manageable, a fixed-price contract with incentives to drive productivity and innovation can often benefit all parties.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

A program manager, public or private, has the responsibility to package the subcomponents of a program into projects in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits and control not available from managing them individually. Contract structure is one tool a program manager has for improving program synergy and success.

There is extensive literature about the most suitable contract forms to use in program delivery. Over the past 30 years, EM has experienced strengths and weaknesses of various contract forms and currently is implementing the IDIQ delivery method to select the best contract form for the task or project.

FINDING: The single-award IDIQ contract vehicle DOE is currently implementing is one approach, though by no means the only one, to implement end-state contracting.

FINDING: The use of IDIQs for end-state contracting entails the use of task orders during the 10-year IDIQ draw period which themselves can have a further 5-year period of performance. The outputs and outcomes of the task orders could collectively progress not only toward an end state of the IDIQ, but also toward an intermediate outcome on the path to site closure. Measuring performance toward this outcome can be done using metrics established at the beginning of the draw period.

NOTE: CR = cost reimbursable; CPPC = cost plus percentage of cost; CPFF = cost plus fixed fee; CPAF = cost plus award fee; CPIF = cost-plus-incentive fee; T&M = time and materials; FPEPA = fixed price with economic price adjustment contract; and FPIF = fixed price incentive fee.

CONCLUSION: Measuring progress toward an end state in an IDIQ contract with multiple task orders necessitates setting metrics at the outset of the draw period aiming toward a defined end state (or intermediate end state in a broader program) that will have been reached at the completion of the IDIQ task orders.

RECOMMENDATION 6-1: The Office of Environmental Management (EM) should establish well-defined, outcomes-based intermediate end states in its 10-year cleanup contracts. Any intermediate outcomes should have clear, measurable metrics to assess site-based (versus task-based) achievement of the defined end states. EM should report progress on these metrics across the portfolio of end-state programs on a quarterly basis and such reports should represent a key EM performance measure.

FINDING: The recently awarded $10 billion IDIQ for the Hanford Central Plateau was described accurately as a cleanup contract and requires the provision of a variety of services with no end state clearly defined. Similarly, EM has declared the $21 billion IDIQ for the Savannah River Site Integrated Mission Completion Contract to be a completion contract. (DOE took bids on the RFP until December 1, 2020.)

CONCLUSION: The definition of end state in the RFP for the Savannah River Site Integrated Mission Completion Contract is essentially correct but needing clear outcomes related to completing the site’s cleanup. IDIQs are typically issued because an agency has not defined the work except in broad terms.

FINDING: In the committee’s interviews with EM project management, they stated that the average size for task orders is approximately $100 million. For a nominal $10 billion IDIQ contract awarded for cleanup, this would require EM to manage 100 task orders over the life of just one cleanup contract. Further, this number of task orders creates a huge residual risk for EM and does not assure an intermediate end state that is outcome focused.

FINDING: There will be substantial work needed to provide sufficiently robust cost estimates for the number of task orders implicit in the ESCM approach in a single-award negotiating environment. Not using the PEP process envisaged in Order 413.3B will compound this.

RECOMMENDATION 6-2: The Office of Environmental Management (EM) should structure task orders on a scale that is appropriate for defining intermediate outcomes and award fewer individual tasks. EM should apply to such task orders the same management oversight as currently required for major systems projects exceeding $750 million in total cost.

REFERENCES

DOE (U.S. Department of Energy). 1995. Estimating the Cold War Mortgage: The 1995 Baseline Environmental Management Report. DOE/EM-0232. Washington, D.C.

______. 2006. Closure Legacy: From Weapons to Wildlife. Washington, D.C. August.

______. 2008. “General Guide to Contract Types for Requirements Officials.” Chapter 16 in Acquisition Guide (March). https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/maprod/documents/AcqGuide16pt1.pdf.

______. 2019. Agency Financial Report: Fiscal Year 2019. DOE-CF-0160. Washington, D.C.

______. 2020. Department of Energy FY 2021 Congressional Budget Request: Volume 5, Environmental Management. DOE/CF-0166. Washington, D.C.

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 1997. Management and Oversight of Cleanup Activities at Fernald. GAO/RCED-97-63. Washington, D.C.

Rocky Flats FSUWG (Future Site Use Working Group). 1995. Recommendations for Rocky Flats Environmental Technology Site. Colorado.