Summary

Formaldehyde is widely present in the environment. It is one of the highest production chemicals by volume, used in many manufactured goods: wood products (e.g., cabinets, furniture, plywood, particleboard, laminate flooring, etc.), permanent press fabrics, and household products (glues, paints, caulks, pesticides, cosmetics, detergents etc.). It is also formed by combustion sources and present in smoke from cigarettes and other tobacco products, and in emissions from gas stoves and open fireplaces. Additionally, it is naturally produced in humans through one-carbon metabolism.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Office of Research and Development’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Program conducts comprehensive scientific reviews that lead to the development of reference concentrations (RfCs) for noncancer outcomes and inhalation unit risk (IUR) values for cancer outcomes for inhaled chemicals. In 1989, the IRIS Program listed formaldehyde as a probable human carcinogen and provided a cancer unit risk estimate (URE). In 1990, a noncancer reference dose (RfD) was provided by the IRIS Program. In 2010, EPA updated its draft IRIS assessment of formaldehyde, which underwent review by an ad hoc National Research Council (NRC) committee. The resulting report was released in 2011. Thereafter, in 2012, EPA began working on a revised draft assessment, convened workshops in 2014, and completed a revised draft assessment in 2017. In 2018, work was suspended on the draft assessment, according to the IRIS website (US EPA 2022). The draft assessment was updated beginning in 2021 before being released in April 2022 as the 2022 Draft IRIS Toxicological Review of Formaldehyde: Inhalation (hereafter referred to as the “2022 Draft Assessment”; the 2010 version is referred to as the “2010 Draft Assessment”). The timeline of EPA’s development of the formaldehyde Draft Assessment in the context of reports from the NRC (in 2011 and 2014) and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) (in 2018 and 2022) is shown in Figure S-1. These reports encouraged the IRIS Program to adopt systematic review methods, to develop a staff handbook with general guidance on the methods used in IRIS assessments, and to develop an a priori protocol for each major IRIS assessment.

In line with its statement of task, the committee considered that any Tier 1 recommendations would be important to address to improve critical scientific concepts, issues, or narrative in the 2022 Draft Assessment. Tier 2 and Tier 3 recommendations could also trigger additional work on the Draft Assessment, including document editing to better clarify and support the assessment’s conclusions. The committee did not conduct an independent hazard evaluation or dose-response assessment, and therefore does not recommend alternative hazard identification conclusions or toxicity values. The committee also was not charged with commenting on other interpretations of scientific information relevant to the hazards and risks of formaldehyde, nor did its statement of task call for a review of alternative opinions on EPA’s formaldehyde assessment. Any other topics that do not fall within the committee’s charge were beyond the purview of this study.

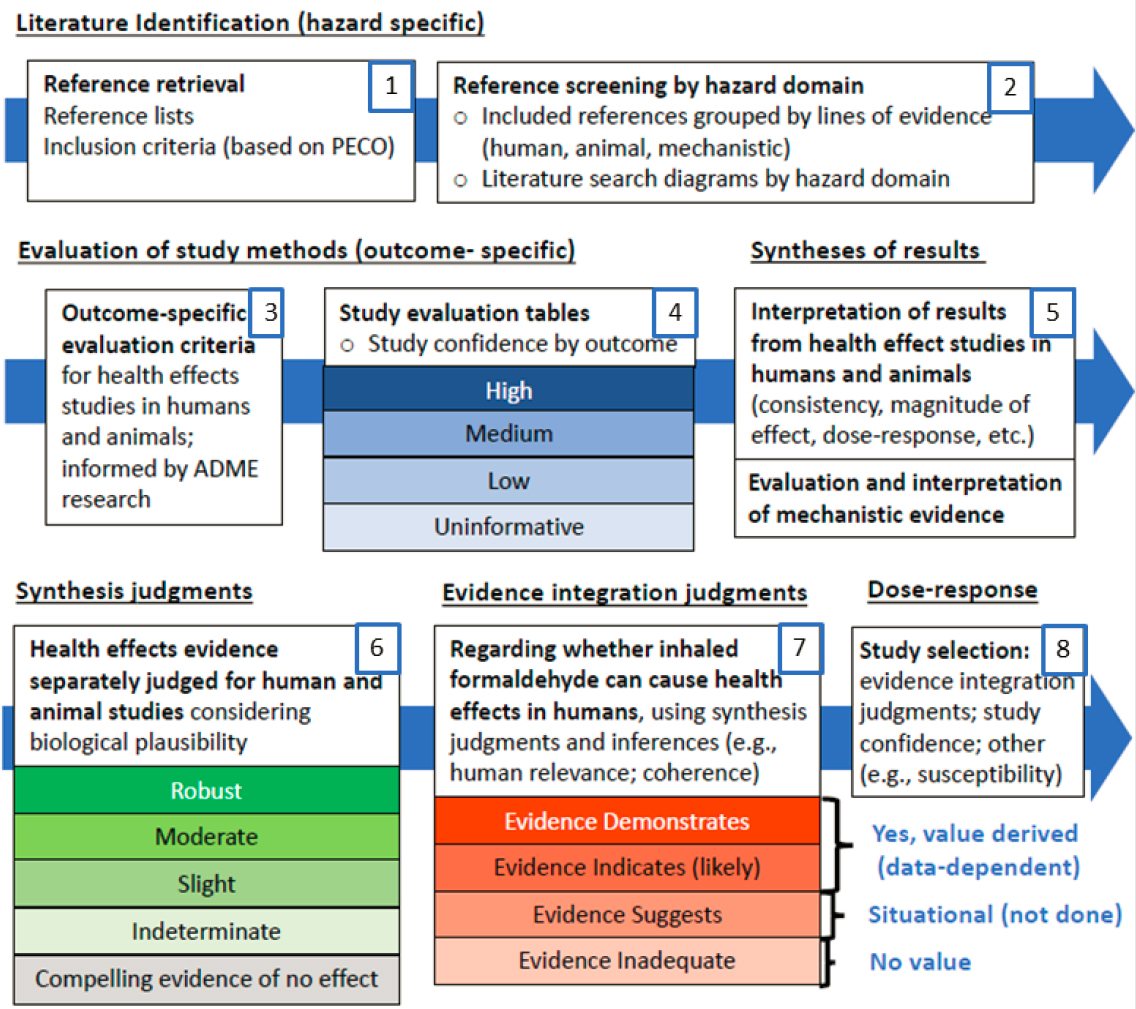

To address its task, the committee organized its review of EPA’s hazard identification and dose-response analyses of noncancer and cancer outcomes around the agency’s overview of its approach to developing the 2022 Draft Assessment (Figure S-2).

STUDY CHARGE, SCOPE, AND APPROACH

The committee’s statement of task is provided in Box S-1. As a comparison for the methods of the 2022 Draft Assessment and their documentation, the committee relied on general principles for conducting a systematic review and for ensuring transparency. To better understand the state

of practice applied in preparing the Draft Assessment, the committee sought the protocols for EPA’s reviews of noncancer, cancer, and mechanistic evidence so they could be evaluated against accepted systematic review methods that existed at the time the Draft Assessment was prepared. The committee also relied on EPA’s responses to queries it posed to the agency.

NOTE: Modified from EPA’s presentation to the committee on October 12, 2022.

The committee provided critiques and suggestions on EPA’s methods for each step in the assessment (documentation of methods, evidence identification, study evaluation, evidence synthesis, evidence integration, and dose-response assessment). For each step, the committee considered the alignment of the 2022 Draft Assessment methods with the contemporaneous state of practice and prior advice to EPA from the National Academies. Transparency in EPA’s systematic review methods implies that the committee should be able to replicate each step based on the information included in the assessment documents or in publicly available supplemental materials. Accordingly, the committee used a case study approach to provide a detailed evaluation of the transparency and replicability of the 2022 Draft Assessment methods, relying on the documentation provided by EPA in the 2022 Draft Assessment and in the written responses to the committee’s queries.

The committee also reviewed the hazard and dose-response conclusions for noncancer outcomes (covering sensory irritation, pulmonary function, respiratory pathology, allergy and asthma, reproductive and developmental toxicity, and neurotoxicity) and for cancer outcomes. This aspect of the committee’s review addressed each step of EPA’s assessment methods for each outcome as used to develop evidence integration judgments and derive risk estimates for formaldehyde. In line with its overall charge, the committee focused its review on whether the 2022 Draft Assessment adequately and transparently evaluated the available studies and data, and used appropriate methods in reaching hazard identification conclusions and dose-response analyses that are supported by the scientific evidence. In its review, the committee also considered the recommendations of prior NRC and NASEM committees, including the 2014 NRC committee that reviewed the formaldehyde assessment of the National Toxicology Program 12th Report on Carcinogens. In accordance with its statement of task, the committee did not conduct an independent assessment of formaldehyde’s hazards or risks.

SUMMARY OF THE COMMITTEE’S FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee provides a number of Tier 1, 2, and 3 recommendations to improve the 2022 Draft Assessment. Key recommendations are provided in this section, and others are presented in the context of the detailed discussion within the main chapters.

RESPONSIVENESS TO PRIOR RECOMMENDATIONS AND DOCUMENTATION OF METHODS

Overall, the committee found that the 2022 Draft Assessment is responsive to the broad intent of the 2011 NRC review of EPA’s 2010 Draft Assessment and the 2014 NRC review of the IRIS process. Yet, while the steps in the systematic review process used in preparing the Draft

Assessment are generally consistent with those outlined in the 2014 NRC report, the assessment does not satisfactorily follow recommendations for problem formulation and protocol development. EPA did not develop a set of specific protocols for the 2022 Draft Assessment in a fashion that would be consistent with the general state of practice that evolved during the prolonged period when the assessment was being developed. Instead, EPA described the assessment methods across the three documents that together make up the 2022 Draft Assessment: the Main Assessment (789 pages), accompanying Appendices (1059 pages), and an Assessment Overview (192 pages). The committee concluded that prepublished protocols are essential for future IRIS assessments to ensure transparency for systematic reviews in risk assessment.

The committee’s review of the 2022 Draft Assessment documents the challenges faced by users of the assessment in navigating the voluminous documentation and understanding the methods used and evidence assessed. Revision is needed to ensure that the methods used for each outcome can easily be found. This can be accomplished by providing a linked roadmap and merging the descriptions of the methods used for each outcome in a single location.

Recommendation 2.1 (Tier 1): EPA should revise its assessment to ensure that users can find and follow the methods used in each step of the assessment for each health outcome. EPA should eliminate redundancies by providing a single presentation of the methods used in the hazard identification and dose-response processes. A central roadmap and cross-references are also needed to facilitate access to related sections across the different elements of the assessment (e.g., Appendixes, Main Document) for the different outcomes analyzed. Related Tier 2 recommendations would amplify the impact of this Tier 1 recommendation in improving the assessment.

Recommendation 2.2 (Tier 2): In updating the assessment in line with the Tier 1 Recommendation 2.1, EPA should further clarify the evidence review and conclusions for each health outcome by giving attention to the following:

-

Using a common outline to structure the sections for each health outcome in order to provide a coherent organization that has a logical flow, by

- adding an overview paragraph to guide readers at the start of sections for each of the various health domains, and

- including hyperlinks to facilitate crosswalking among sections within the document;

- Moving lengthy, not directly used information to an appendix;

- Including a succinct executive summary in the Main Assessment; and

- Performing careful review and technical editing of the documents for consistency across the multiple parts of the 2022 Draft Assessment, including across the Assessment Overview and Appendices. (The Assessment Overview could be entirely removed if the above recommendations were carried out.)

The sections that follow address the specific steps depicted in Figure S-2.

EVIDENCE IDENTIFICATION (STEPS 1 AND 2)

Generally, the committee found the literature searches to be adequate. EPA appears to have sufficiently harmonized the approaches for the pre- and post-2016 literature searches that were conducted using two different methods, and the approaches used were consistent with the state of practice at the time. Although the search strategies are adequately documented, the origins of the

various population, exposure, comparator, and outcome (PECO) statements are less clear. In particular, across noncancer outcomes, the rationale for excluding studies on the basis of the populations, exposures, and outcomes studied is not well documented. For allergy and asthma, for example, the age cutoffs are not stated and clearly applied, and it is unclear whether a broader set of immunopathologies was considered before the focus was narrowed to prevalent allergies and prevalent asthma. For sensory irritation, the rationale for excluding outdoor air studies is unclear. For respiratory pathology, the search terms and inclusion and exclusion criteria used to search human and animal evidence are discrepant.

Recommendation 2.3 (Tier 2): EPA should expand the text explaining the choices of the elements of the PECO statements.

STUDY EVALUATION (STEPS 3 AND 4)

EPA provides overall and outcome-specific evaluation criteria that are generally consistent with the common domains for risk-of-bias analysis. However, the information is presented in several different locations in the documents, and in some cases is inconsistently presented and integrated across the documents. As a result, for several noncancer outcomes, the committee was challenged to reconstruct the study evaluation approach and how the criteria were applied for study evaluation.

The considerations listed for study confidence classification and evaluation of each study by at least two independent experts are adequate. However, the committee’s evaluation revealed some inconsistencies in how evaluation criteria are described and applied. Such inconsistency was broadly evident in the committee’s review of EPA’s evaluation of human and animal studies across noncancer outcomes (including for sensory irritation, pulmonary function, respiratory pathology, allergy and asthma, reproductive and developmental toxicity, and neurotoxicity). In multiple instances, individual ratings of confidence for noncancer studies may merit more careful reassessment, whereas others are merely described inconsistently.

Overall, while outcome-specific criteria for evaluating the human and animal studies were generally appropriate, the committee could not satisfactorily identify the final criteria that were applied, as well as the judgments made in determining overall study confidence for both human and animal studies. Inconsistencies between the stated criteria and the rationale for conclusions on study confidence were evident.

Recommendation 2.4 (Tier 2): EPA should thoroughly review the 2022 Draft Assessment documents to address issues of consistency and coherence so as to ensure that its methods can be applied and replicated with fidelity. The reviews for each outcome in Chapters 4 and 5 provide more specific guidance.

EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS (STEPS 5 AND 6) AND INTEGRATION (STEP 7)

For evidence synthesis, the strength-of-evidence categories and how they were applied to the overall evidence judgments are generally clear and appropriate for the human and animal evidence streams.

While drawing on long-established methods for inferring causation, the 2022 Draft Assessment deviates in several respects, including (1) blurring of the boundary between evidence synthesis and integration, and (2) the choice of terminology used to describe the strata in the four-level

schema for classifying strength of evidence. Additionally, in some instances the narratives concerning the evidence integration step are too terse to fully explain why EPA came to specific confidence conclusions.

Recommendation 2.5 (Tier 2):

- The 2022 Draft Assessment should be edited to more sharply demarcate the synthesis and the integration of evidence discussions.

- EPA should expand the narrative descriptions of the evidence integration step, or should follow published methodology while providing detailed explanation of any adaptations.

Regarding mechanistic evidence, the committee found that EPA is thorough and transparent in identifying the relevant information. However, the definition of “impactfulness” and how this concept was applied are not well described. Similarly, the term “other inferences” is used in the sections on integration of cancer evidence, but is not explained.

Recommendation 2.6 (Tier 2): To increase the transparency of the evaluation of mechanistic data, EPA should clarify key terms (e.g., “impactfulness,” “other inferences”) and their application to specific studies. “Impactfulness” can be defined (in Table F-12 and elsewhere), and “other inferences” can be explained in discussing the approach to evidence integration in the Preface on Assessment Methods and Organization.

Regarding toxicokinetics, EPA used the data in the evidence synthesis step and applied the available models to derive candidate RfCs for respiratory tract pathology in animals in a manner consistent with its state-of-practice methods. Transparency could be enhanced by explicitly identifying the models used to derive flux values in the summary tables, and by improving documentation of the dosimetry approaches in the tables and text.

For noncancer outcomes comprising effects on pulmonary function, respiratory pathology, allergy and asthma, reproductive and developmental toxicity, and neurotoxicity and sensory irritation, EPA presents hazard identification conclusions supported by the available scientific evidence from humans, experimental animals, and mechanistic studies. The assessment could be strengthened by clarifying the basis for summary judgments, such as by referencing the specific studies relied upon in reaching conclusions.

Recommendation 4.7 (Tier 2): EPA should clarify the basis for its synthesis judgments and provide additional information about the studies on which they are based, such as the formaldehyde levels observed, as well as the exposure ranges or other measure of variability. The study summary tables (Tables 1-6 to 1-9) should be updated to provide an organized distillation of the points made in the evidence synthesis text.

With respect to cancer hazard identification, EPA used its state-of-practice methods to synthesize the current state of the science and presents hazard identification conclusions supported by the available scientific evidence from humans, experimental animals, and mechanistic studies. For lymphohematopoietic cancers, EPA was responsive to previous recommendations from the NRC and focused on the most specific diagnoses of myeloid leukemia, lymphatic leukemia, multiple myeloma, and Hodgkin lymphoma. Clarifications are needed with respect to the summary statements, and some terminology (e.g., “other inferences”) needs to be defined, as noted above.

Recommendation 5.1 (Tier 2): While the narrative describing the application of criteria for each site is well done, EPA should enhance clarity by providing explicit statements in section 1.2.5 summarizing synthesis judgments for each criterion (consistency, strength, temporal relationship, exposure-response relationship, etc.).

DOSE-RESPONSE ASSESSMENT (STEP 8)

The committee found the considerations for selection of dose-response studies to be reasonable, although the discussion in multiple places in the documents made it difficult to determine what the considerations were and how they were applied.

EPA provides criteria for study inclusion in the dose-response assessment, but does not include any discussion of how these criteria were applied to the specific studies chosen for dose-response. Using the Hanrahan et al. (1984) study as a test case, there are inconsistencies between the characteristics of the study and EPA’s criteria for selecting studies for dose-response analyses. Similar inconsistencies were identified across the noncancer outcomes considered by the committee.

Recommendation 4.6 (Tier 2): EPA should clarify and clearly state the criteria used to select the studies for dose-response analysis of noncancer endpoints.

Recommendation 4.16 (Tier 2): EPA should carefully address the following points regarding the derivation of the RfC:

- Fully disclose data extracted from original study reports using HERO or other means.

- Cite relevant guidance documents regarding the use of a mean versus median and arithmetic mean versus geometric mean to estimate a lowest observed adverse effect level or no observed adverse effect level.

- In reanalyzing data from published studies, the use of raw data is preferred. Aggregated data may be used when appropriate. At a minimum, group size, group mean, and a measure of variance (e.g., group standard deviation or standard error of the mean) for each exposure level are needed to capture data variation in a reanalysis of dose-response.

- Avoid fitting a dose-response model that has as many parameters as the number of distinct aggregated data points taken from the published literature. Report and consider only models that meet the goodness-of-fit criterion EPA accepts.

- To ensure that the resulting benchmark concentration lower bound is not artificially overestimated, better account for within-group variability in the dose-response analysis of Hanrahan et al. (1984) to address limitations arising from reliance on only secondary, aggregated rates per exposure group that were extracted from the plot of the originally fitted model.

- Be more explicit as to how the final RfC was chosen (in Figure 2-2 of the 2022 Draft Assessment and elsewhere).

Regarding the dose-response assessment for cancer endpoints, the committee found that EPA used approaches consistent with its state-of-practice methods to derive the inhalation unit risk estimates. The analyses generally followed the process outlined in the 2022 IRIS Handbook and were consistent with the 2005 Guidelines for Carcinogen Risk Assessment. As documented in Appendix

D and in sections on cancer dose-response analyses, the decision points and analyses were also responsive to the recommendations of the 2011 NRC committee.

The derivation of the unit risk is documented in approximately 200 pages in total across the three documents in the 2022 Draft Assessment, and some redundancies are evident within and across the documents. The sections documenting the derivations based on epidemiological evidence are transparent, and overall are well written and accessible.

Specific recommendations regarding the cancer dose-response assessment concern the criteria for study selection, the procedure and justification for pooling the data from two animal studies into one analysis, the discussion of uncertainties and variabilities, and the characterization of inhalation unit risk estimate, as detailed below.

Recommendation 5.4 (Tier 2): While the criteria for selecting the Beane Freeman et al. (2013) study can reasonably be discerned from the 2022 Draft Assessment, EPA should provide clearer statements of the criteria and comparison of studies with such criteria, in tabular format, to improve transparency and clarity. EPA should add to such a table other studies that evaluated the same cancer outcome so it is apparent why the selected study was superior for the purposes of dose-response analysis.

EPA identified three high-confidence and three medium-confidence long-term (>2-year) animal studies of formaldehyde in F344 rats for the purposes of dose-response analysis. The rationale for selecting some but not all of the studies and the procedure for combining data from two selected studies are not clearly presented. In joint analysis of the combined data, the description for the models used is not sufficiently transparent, particularly regarding the estimation of some key parameters.

Recommendation 5.8 (Tier 2): EPA should describe more clearly the procedure and justification for pooling the data from two animal studies into one analysis, and clarify that combined and corrected incidence data are contained in the Bermudez memorandum, which is not readily accessible to the public. The individual animal data for time-to-tumor occurrence used in the model should be provided in an appendix.

Recommendation 5.9 (Tier 2): To enhance transparency, EPA should provide additional detail on the modeling, including constraints imposed on model parameters, the results of model fitting (goodness-of-fit test), and the approach used to define lag parameters. The relationship between administered dose and the DNA–protein crosslinks and flux dose metrics should also be provided. Given the uncertainties in the dose surrogates, a dose-response analysis and benchmark concentration calculations using administered concentrations should be provided as a point of comparison.

Recommendation 5.10 (Tier 2): EPA should organize the discussion of uncertainties and variabilities in a manner that is easier to follow, such as by models or by process (models, benchmark concentration estimation, lower dose extrapolation, or extrapolation from animal data to humans).

Recommendation 5.12 (Tier 2): EPA should discuss the extent to which the inhalation unit risk estimates based on animal squamous cell carcinoma data and mechanistic data provide supporting evidence for the inhalation unit risk based on the human nasopharyngeal carcinoma data.

Recommendation 5.15 (Tier 2): In the discussion of uncertainties and confidence in the inhalation unit risk for myeloid leukemia, EPA should include the unknown dose rate-response relationship, the choice of statistical model and method, and the lack of understanding of mechanism. The three estimates in Table 2-35 should be presented as alternative, low-confidence inhalation unit risk estimates for myeloid leukemia without selection of a preferred estimate. EPA should not characterize the combining of other/unspecified leukemia with myeloid leukemia as “the best approach.”

THE PATH FORWARD

EPA’s 2022 Draft Assessment has been revised over a period spanning more than a decade and has been improved substantially. During that time, the methods used by the IRIS Program have evolved, prompted in part by the recommendations of the 2011 NRC report and subsequent reports of the National Academies. The 2011 report recognized that a period of change in methods used by the IRIS Program would begin if its recommendations and suggestions were followed, and cautioned that revisions to the 2010 Draft Assessment should not await finalization of any new methods.

The 2022 Draft Assessment was developed over a period of evolving methods within EPA and externally. The revised 2022 Draft Assessment follows the advice of prior National Academies committees, and its findings on hazard and quantitative risk are supported by the evidence identified.

In addressing its charge, the committee had to be able to identify the methods used, compare them against the state of practice for the IRIS Program, and assess their replicability. The committee did not find it easy to fulfill its charge given the organization and scope of the three documents, together totaling more than 2,000 pages, and the presentation of the review methods in several locations across the three documents. The IRIS Program did not consolidate protocols for the various outcome reviews, as would be current practice. Many of the committee’s findings and recommendations relate to the fragmented description of methods across the documents and insufficient clarity in their presentation.

In the chapters that follow, the committee reviews in detail EPA’s methods and conclusions and provides detailed recommendations for improving the clarity, accuracy, and usability of the final assessment. A major focus of the committee’s recommendations is revisions needed to provide a clearer description of the methods used in order to facilitate their consideration by readers. At present, the description of methods in several places throughout three lengthy documents is perhaps the most critical area for structural and editorial revisions. Other recommendations point to opportunities to harmonize the assessment narrative across health outcome domains and to bring greater consistency by structuring them more carefully around the assessment’s overall review framework. Implementation of the committee’s recommendations would strengthen EPA’s conclusions on the many noncancer outcomes reviewed, as well as the cancer hazard identification and dose-response conclusions. Revisions are needed to achieve the overall objective of making the assessment’s methods sufficiently accessible for its users, and to facilitate access to related sections across the different elements of the assessment for the different outcomes analyzed.

The committee notes that according to the IRIS Program’s website:

EPA’s mission is to protect human health and the environment. EPA’s IRIS Program supports this mission by identifying and characterizing the health hazards of chemicals found in the environment.

The 2022 Draft Assessment, which addresses a widely used, high-volume production chemical, needs to be completed to support EPA in fulfilling its mission. The committee acknowledges the significant effort made by EPA to improve the assessment since the 2010 Draft Assessment was reviewed. This report provides a number of specific Tier 1, 2, and 3 recommendations to guide the assessment’s finalization, and the committee encourages EPA to implement all of the needed changes. A confined set of revisions will enhance clarity and transparency. Overall, the committee’s judgment is that EPA should undertake its recommendations expeditiously to complete a revised assessment document that can be implemented without delay.