In the United States, an apple grower knows what pesticides the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has approved for use in apples, their application rates, and preharvest intervals. Similarly, a dairy farmer and his/her veterinarian can look at a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved label on an FDA-approved veterinary drug and know whether the drug can safely be used in cows producing milk and for how long the milk must be discarded. Domestic food manufacturers, food warehouses, and farms recognize that they can be inspected and their products sampled. Domestic producers worry about maintaining the integrity and good reputations of their brands. U.S. trade organizations educate their members about food safety and FDA regulations. When a foodborne outbreak occurs, the FDA and states can investigate quickly and usually track down the source.

Imported foods come to the United States from nearly 200 countries, none of which have exactly the same pesticide, food additive, and veterinary drug approval systems as the United States, and many of which do not have such systems at all. Foreign producers may be ignorant of U.S. food safety requirements or may produce for multiple foreign markets.

Domestic food safety systems in exporting countries may vary from excellent to nonexistent. Potable water may not be available for irrigation; waste and sewage treatment may be absent or inadequate. Nevertheless, many exporting countries that lack domestic food safety programs are willing to do what they can to ensure export markets for their products, including employing food safety measures to satisfy importing country requirements if doing otherwise could cause problems or a loss of market access.

While no importing country is able to examine all imported foods for all possible chemical residues and contaminants, microbiological pathogens, and physical hazards, many importing countries have achieved excellent imported food safety records by focusing resources on higher-risk foods and preventive mechanisms and confronting food-related public health problems when they occur. As discussed in this appendix, import programs for food safety can employ many methodologies to foster safer imports and provide incentives for foreign producers/food importers to comply with importing country requirements. Just as imported food presents different food safety challenges from those encountered with domestically produced foods, so, too, do they require a different paradigm for regulation.

BACKGROUND

The FDA’s overall foods program is distinct in several respects from the agency’s other public health regulatory program areas. First—with the exception of food and color additive approvals and premarket notification for certain foods—foods under FDA jurisdiction, whether produced within or outside the United States, do not require premarket approval. Thus, the foods program overall is generally a postmarket program. A second difference is that the foods regulatory program, to date, is not supported in any way by user fees, while all agency premarket approval programs are, as well as all agency export certificate programs, except for foods. Thus the foods program, at present, is totally dependent on congressional appropriations. Third, whereas most of the FDA’s other centers generally have regulatory autonomy over their respective product areas, the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) must interface with other federal departments and agencies, as well as the 50 states, to ensure consistent and comprehensive coverage of the entire U.S. food supply at all levels. While the regulatory roles of U.S. food safety partners are well delineated, smooth operation of the U.S. food control system requires constant communication to ensure that the roles mesh efficiently. Finally, the foods program differs from other FDA programs in that, by volume of product and number of consignments, the realm for regulatory oversight is vast. These four differences are important to remember and fundamental in considering potential improvements in the FDA’s foods program because one needs to understand

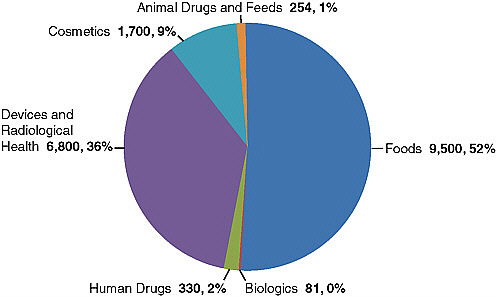

FIGURE E-1 Fiscal year 2009 estimated import lines by program area (in thousands): total 18.7 million lines.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Steven Solomon, Office of Regulatory Affairs, July 2009.

the regulatory context in which the program operates in regulating 80 percent of the nation’s food supply (Meadows, 2006). The differences between other FDA programs and the foods program are especially apparent in light of the special challenges inherent in regulating imported food safety.

The estimated total of food import entry lines3 for fiscal year (FY) 2009 is 9.5 million, or 52 percent of the estimated total of 18.7 million lines for all FDA-regulated imported products (see Figure E-1).4 Food imports now account for approximately 15 percent of the foods and 80 percent of the seafood consumed in the United States (Acheson and Glavin, 2007). In addition to quantity, the variety of imported product types is challenging to regulate, ranging from highly perishable produce, to dairy, to shellfish, to canned products, to bakery goods. The number and types of countries exporting products to U.S. shores are also wide-ranging, from less developed countries with, at best, rudimentary food regulatory systems to developed economies with highly regarded food safety controls.

Although many countries may have a limited spectrum of products that they export, almost every country exports agricultural commodities, and almost 200 countries export such commodities to the United States (FAS, 2009).

Regulating imported foods can be complex. With such foods, the FDA may need to consider not only the exporting country’s food control system but also the environment in which the food is grown, including the availability of potable water for irrigation and washing, and diseases of farm workers and farm animals that could impact the safety of the food. In addition to working with other U.S. food-related agencies and states, as it does for its domestic food safety program, for its imported food program the FDA must interface with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP, in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security), the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the Foreign Agricultural Service, the Departments of State and Commerce, and exporting country governments themselves. Compliance with international trade agreement obligations is important in dealing with imports, including ensuring that the scientific basis for all FDA regulatory measures that may impact trade is clear and no more trade-restrictive than necessary. Imported foods are infrequently examined at the border, often being sampled for analysis less than 1 percent of the time (GAO, 2008).5 There are simply too many imported food shipments for the FDA resources available. Certainly there are too many foreign firms to consider on-site inspections on a routine basis, and the few such inspections performed can only provide a snapshot of a country’s internal food regulatory system. Most foreign facilities that produce, manufacture, process, or store foods consumed in the United States must register under the bioterrorism regulations (FDA, 2009a); however, there is no mechanism for putting foreign food producers and shippers on notice that U.S. food safety laws must be followed, other than the laws and regulations themselves. Clearly, the FDA’s imported food program needs a fresh review.

The Concept and Design for the FDA’s Imported Food Program

In large part, the FDA’s food laws and programs were built around a domestic food industry. Domestic food facilities were to be inspected, with the FDA focusing on products involved in interstate commerce and states concentrating on retail and intrastate establishments. Sampling of food was conducted during inspections of firms to detect problems or to confirm a safety concern when one was suspected. Sampling of products being moved in commerce was done primarily on a surveillance basis and often close to

the farm gate or boat. Foods were not transported long distances; only a tiny fraction of foods consumed came from other countries, and these were traditional imports such as bananas and coffee.

Until very recently, the FDA approached food imports with a philosophy similar to that of its domestic program. All foods, whether domestic or imported, must comply with the same food safety standards, and, as with domestic foods, it is the responsibility of foreign companies—growers, manufacturers, packers, warehouses—and importers to know and comply with applicable laws and regulations. The FDA maintains a comprehensive website that provides all this information, generally in English only (FDA, 2009b). Although it can be argued that knowing the food safety requirements of the importing country should be integral to conducting a food export business, it may also be noted, with some exceptions, that until quite recently the FDA did not actively pursue outreach to foreign countries, their industries, or importers regarding its food safety requirements. The agency has conducted annual meetings with Washington embassies on its programs (in all FDA product areas). It also carried out a massive outreach program on the implementation of its bioterrorism regulations a few years ago through meetings with embassies, World Bank–assisted regional vide-conferences, and question/answer sessions at the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Geneva.

In the case of meat, poultry, and processed egg products, by law the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) cannot grant market access until the exporting country’s system has been evaluated and determined to be equivalent to the U.S. system in the level of protection provided.6 By contrast, the FDA has seen its job with food imports primarily as one of checking the products at ports of entry. However, the FDA cannot begin to examine the vast number and variety of food shipments arriving at about 300 ports of entry throughout the United States (GAO, 2008).

Today, with approximately 15 percent of all foods consumed in the United States being imported, amounting to millions of shipments and hundreds of millions of dollars, the FDA continues to look at as many shipments as possible and sample products mainly on a surveillance basis—that is, not “for cause.” Nevertheless, recognizing that its import surveillance resources are limited, the agency has always prioritized food safety sampling in its compliance programs to look for chemical contaminants, microbes, and other problems in specific foods in which such problems are more likely to be found based on historical and available intelligence.

The FDA’s Process for Dealing with Imported Foods

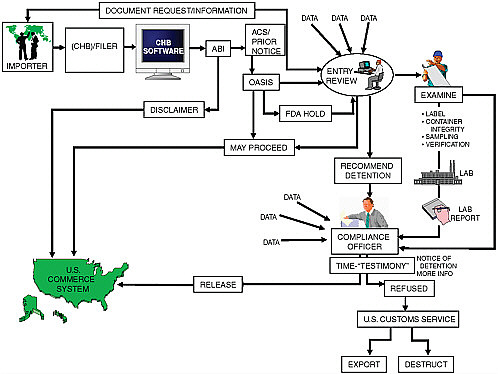

The process the FDA follows in examining food import documents and the foods themselves is summarized in Figure E-2 (Veneziano, 2008).

The procedures for the FDA’s handling of imported foods are found in the FDA’s Investigations Operations Manual, Chapter 6, “Imports” (FDA, 2009c). Any article that is offered for entry into the United States and subject to the laws administered by the FDA with a value greater than $2,000 is considered a formal entry. Formal entries require that a bond be filed with CBP; this bond includes a condition for redelivery of the merchandise at any time or, in case of default, the collection of liquidated damages. Notification of the CBP entry is usually accomplished by electronic submission through the CBP Automated Commercial System (ACS). The FDA reviews the entry documents electronically through the FDA/ACS interface and decides whether the shipment may proceed into U.S. commerce or should be examined further. The FDA also reviews informal entries and, if it decides to take action on such an entry, asks CBP to convert it into a formal consumption entry.

The Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 (the Bioterrorism Act) requires that domestic and foreign facilities that manufacture, process, pack, or hold food for human or animal consumption in the United States register with the FDA (FDA, 2009a). The Bioterrorism Act also requires that the FDA receive advance notice of food to be imported into the United States before the food arrives—called prior notice (FDA, 2009d). The information required for prior notice to the FDA is basically the same as that usually required by CBP. Prior notices can be submitted either through the Automated Broker Interface/ACS or the FDA’s Prior Notice System Interface. Products being transported by road require 2 hours prior notice, those being transported by rail or air 4 hours notice, and those by water 8 hours. As a rule, prior notice must be given for all foods under FDA jurisdiction, with the exception of foods made by individuals as a gift or food carried with a traveler for personal consumption or consumption by family or friends. Food that is imported or offered for import with inadequate prior notice is subject to refusal and holding at the port or in secure storage.

The FDA’s Prior Notice Center, operating 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, reviews the prior notices received. The review process is designed to identify food products that may pose serious risks to public health under the Bioterrorism Act so that appropriate action can be taken when the food arrives at the port of entry. If the food meets the prior notice requirements, the FDA’s Operational and Administrative System for Import Support (OASIS) data system review (discussed later in the section on Predictive Risk-Based Evaluation for Dynamic Import Compliance Target-

ing [PREDICT]) determines whether further evaluation of the shipment is necessary under section 801(a) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) before the food can enter U.S. commerce. For example, if a particular product falls under an FDA import alert, OASIS may flag the shipment for detention without physical examination (DWPE). The food may also be flagged for sampling or examination under a CFSAN compliance program or sampling assignment. In addition, an FDA reviewer may decide to examine a product (e.g., to check its labeling or the integrity of cans) or collect samples for analysis in an FDA laboratory.

If a product arrives at a point of entry where an FDA official is not expected to be present, the responsible FDA district office may ask CBP to collect a sample for forwarding to the FDA servicing laboratory. If the shipment is found to be in compliance after examination or analysis, the importer of record, consignee, or filer and CBP receive a Notice of Release. If a violation is found or the product appears to be in violation, the district office will decide whether the product should be detained. The filer, owner, and consignee, where applicable, are advised of such action by a Notice of Detention and Hearing. This notice specifies the nature of the violation and designates a site where the owner or consignee can come for an informal hearing. The owner may be able to correct the problem by relabeling or reconditioning the product, in which case the product is released. If this is not possible or not done when possible, the district may issue a Notice of Refusal of Admission by request of the importer or on its own decision. The FDA charges for its services in overseeing relabeling, destruction of product, or other action and sends these charges to CBP, which in turn sends a notice for payment to the identified importer of record. The remittance by the owner or consignee must be to CBP, not to FDA district offices. CBP will issue a demand for redelivery at the request of the FDA. Exportation of refused merchandise is done under CBP supervision. Failure to redeliver results in CBP issuance of a liquidated damage for up to three times the value of the shipment.

The FDA’s New Foreign Posts

One recent step forward in working with other countries on food safety is the FDA’s opening of foreign posts. These posts are located in China (Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai), the European Union (EU) (Belgium, Italy, and the United Kingdom), India (Mumbai and New Delhi), and Latin America (Chile, Costa Rica, and Mexico). A table provided by the FDA, dated August 20, 2009, gives the status of staffing of these foreign posts (GAO, 2009). Fifteen of these positions are to be focused specifically on foods, as opposed to other FDA jurisdictional areas. The foreign posts have many purposes, including technical cooperation with foreign regulators,

information exchange, better understanding of each other’s systems and requirements, and, where appropriate, inspections.

Differences Between Domestic and Imported Food Regulation

All in all, differences between the FDA’s domestic and imported food programs are readily apparent. With domestic firms, FDA field offices have access to and the ability to inspect the firms. They know where these firms are. The domestic food industry is more likely to know, understand, and be constrained by U.S. food safety laws. Industry trade and agricultural organizations actively communicate changes in U.S. regulations to firms and farmers. U.S. farmers and processors have access only to U.S.-approved pesticides and food and color additives, and thus cannot use products banned or never approved in the United States. The same applies to animal drugs used in meat or poultry production, recognizing that meat and poultry regulation falls under the purview of USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). And when a significant regulatory action is taken within the United States, the impact is felt not only by the target of that action but also by the industry as a whole, as industry trade groups publicize such actions to their membership. With imported foods, foreign producers may have difficulty understanding or accessing FDA requirements (although the FDA has put more foreign-language information on its website). Foreign producers may not have access to EPA-approved pesticides or FDA-approved veterinary drugs. Or producers, exporters, and importers simply may not do the homework. Despite globalization of the marketplace, word usually does not travel very far within a country when the FDA takes action on import shipments. The affected country may correct the immediate problem, but rarely does the message reach other countries to have a deterrent effect. Because of these and other differences between the FDA’s domestic and imported food programs, the agency faces more challenges in regulating imported foods in many respects.

The FDA and Food Exports

Unlike a number of other U.S. agencies that deal with food, the FDA does not have a food export program per se. The FDA was established as a scientific regulatory agency that would protect the U.S. consumer, and that has remained its primary mission. Until fairly recently, the statutes underpinning the FDA’s mission did not focus on responsibilities outside U.S. borders. In 1996, Congress passed the FDA Export Reform and Enhancement Act, which affirmatively established export responsibilities, but very little of this act applied to foods. In fact, a system of user fees for issuing export certificates for drugs and devices was included in the law, but nothing was

included on export certificates for foods. The FDA continues to discourage the issuance of food export certificates of any sort because the cost of their preparation far exceeds the $10 fee the agency collects under Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) provisions (actually, even that small fee does not go into supporting the export certificate activity within CFSAN). The FDA’s expectation is that the private sector should be responsible for knowing and observing the food safety requirements of other countries when exporting foods. The FDA has no part in monitoring the safety of food shipments exported from the United States, although all foods produced within the United States are subject to the FDA’s regulatory oversight. Generally, the FDA is willing to say, when it does issue an export certificate, that the product produced in the United States was subject to the laws of the United States, or words to that effect. The FDA does, however, work closely with other countries when they find an unsafe U.S food product to determine the cause and correct the situation. The same foods may pose a risk to the U.S. population or to other countries. The FDA also notifies governments of other countries when U.S.-produced foods found to be adulterated have been exported abroad.

Other U.S. food-related agencies, such as FSIS, the Federal Grain Inspection Service, and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), have export trade-related missions and laws to enforce. These agencies may require and issue export certificates or mandate and demonstrate equivalence of their programs to those of foreign systems. The FDA does have export rules under section 801(e) of the FDCA, basically saying that the agency will not find a product adulterated or misbranded if it is marked for export, accords with the laws of the importing country, was never offered for sale in U.S. commerce, and meets the foreign purchaser’s specifications. It is important to note, however, that this provision is applicable only when a product is found to be adulterated or misbranded. The FDA does not routinely check food products being exported from the United States.

OTHER FEDERAL AGENCIES’ APPROACHES TO REGULATING IMPORTED FOODS

Several agencies have responsibilities in regulating various aspects of the importation of food. For present purposes in comparing regulatory approaches, the focus is on USDA’s FSIS—responsible for the safety of meat, poultry, and processed egg products—and its APHIS, responsible for protecting U.S. agriculture (which may include fresh produce, meat and poultry, live animals, and forests) from exotic diseases and pests.

FSIS

Under the Federal Meat Inspection Act (FMIA), the Poultry Products Inspection Act, and the Egg Products Inspection Act, imported products are prohibited from entering the United States unless the exporting country meets all food safety public health standards applicable to similar products produced in the United States. FSIS evaluates foreign regulatory systems in advance of any product being exported to ensure a program and requirements equivalent to those of the United States. Although FMIA contained the concept of “at least equal to” prior to the WTO obligation in the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures that WTO members allow for equivalence of other countries’ food control systems (Article 4), FSIS rethought its program after the SPS Agreement went into effect to ensure full compliance with the Agreement and prepared new guidance on FSIS equivalence procedures (FSIS, 2003).7

FSIS deals directly with the competent authority in the exporting government in negotiating the equivalence determination, as the government is responsible for both demonstrating and maintaining the equivalent system. FSIS’s import program uses a three-part process to determine and maintain equivalence: (1) recurring analysis of the salient laws, regulations, and implementing policies and discussions with the exporting country to understand how the program operates; (2) on-site audits to verify the delivery of the program; and (3) continuous port-of-entry inspection of products shipped from eligible countries and foreign establishments. FSIS does not conduct actual inspections of facilities in the foreign country or certify foreign establishments for export to the United States. After a country has been judged to have an equivalent food regulatory system, FSIS relies on the country to carry out daily inspections, and the country’s chief inspection official must certify a list of those establishments operating under its control that meet U.S. import requirements. FSIS also requires consignment-by-consignment import certificates. Eligible countries are listed in FSIS regulations 9 CFR 327.2 for meat, 381.196 for poultry, and 590.910 for egg products. There were 29 countries actively exporting meat, poultry, and egg products in 2008, with Canada being the only country exporting

|

7 |

The FDA partnered with FSIS in preparing the first version of this guidance, as the FDA was at the time preparing equivalence guidance of its own. The FDA’s draft guidance was published in 1997 (Draft Guidance on Equivalence Criteria for Food, 62 FR 30593, June 4, 1997). Final FDA guidance was never published. Instead, the FDA turned its full attention to working within the Codex Alimentarius process on the preparation of the Codex guidance on equivalence (Guidelines on the Judgment of Equivalence of Sanitary Measures Associated with Food Inspection and Certification Systems, CAC/GL 53-2003, www.codexalimentarius.net/download/standards/10047/CXG_053e.pdf). |

egg products (FSIS, 2008). An FSIS presentation on its equivalence determination process is available online (Swacina, 2004).

APHIS

APHIS’s responsibilities extend to protecting animal and plant health, as opposed to protecting humans from unsafe foods. Therefore, for present purposes, it is important simply to be aware that APHIS has oversight over imported food to ensure that exotic diseases and pests that might threaten U.S. agriculture and forests are not brought into the United States. In exercising its authority, APHIS requires import certificates and issues export certificates pertaining to animal and plant health to meet other countries’ needs in safeguarding against the entry of exotic animal and plant diseases and pests into their countries (APHIS, 2008). APHIS also evaluates and establishes quarantine treatments for foodstuffs needing treatment before entering the United States. In addition, it works closely with countries on their disease and pest status, which bears on whether and under what conditions they can export to the United States. While APHIS sets the rules, CBP has operational responsibility for implementing these rules at the border.

ROLES OF STATES IN REGULATING FOOD IMPORTS AND EXPORTS

As a general rule, states have been responsible for regulating foods in intrastate commerce, while the FDA’s authority focuses on foods in interstate commerce, which include foods moving in international commerce to or from the United States. Thus, states have not had a significant role in regulating imported foods, except those already in domestic commerce. States concentrate on retail food stores, restaurants, grocery stores, roadside stands, and so on. They usually have embargo authority, which the FDA does not, and can use this authority when partnering with the FDA in controlling the movement of adulterated foods when a problem arises. The FDA and the states work together, often through the Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO), to promote consistency in state food laws and their implementation (e.g., model food laws and the Food Code). Through federal–state contracts, the FDA deputizes state officials to co-duct FDA inspections of food facilities; these inspections became increasingly commonplace as the FDA’s food program resources diminished. The FDA currently has 42 of these contracts, accounting for more than 10,500 inspections a year, including Good Manufacturing Practices sanitation, seafood and juice Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), and low-acid canned food inspections (Solomon, 2009). States have taken actions to stop the sale of imported Grade A dairy products, not because

the products were adulterated but because they were not produced under the federal–state cooperative program for such products. Also, a few states have tested imported foods in domestic commerce for pesticides and examined imported dairy products to check for compliance with the federal–state Grade A program. In these cases, results have been shared with the FDA. Recently, the FDA and the states have been considering giving state inspectors a larger role in dealing with imported foods.8

While not a food import issue per se, it should be noted that virtually all states issue export certificates for food and other products produced in the state. During meetings of the Export Certificate Working Group under AFDO, a number of states suggested to this author, who chaired that group, that the federal government should bear the full responsibility for issuance of export certificates, which they regard as a federal government matter involving international trade. Nevertheless, when the flow of international commerce can be hastened for an in-state product, the states are willing to issue certificates—if necessary within a 24–48 hour time frame—while the FDA may take significantly longer to issue a certificate. Most states charge a fee, usually modest but up to around $175, for a certificate. Their certificates may attest to free sale, the regulatory standing of a firm, or other matters that can be substantiated without laboratory tests or on-demand inspections. The State of Oregon has a special unit that provides fee-for-service laboratory testing as a service to industry to support issuance of export certificates (Oregon Department of Agriculture, 2009).

IMPORTED FOOD SAFETY CONTROL SYSTEMS IN OTHER COUNTRIES

In reviewing the food safety systems of other countries, it is useful to know the philosophical, political, or event-driven basis for their development and structure. In any case, it can be instructive to learn more about those programs that provide the citizens of other countries with safe and high-quality foods. While recognizing that it is impossible to provide detail here on the background, legislation, organization, and operations of each such food control system, several such systems are highlighted in this section (see also Appendix C).

Canada

Canada reorganized its food safety system in 1997. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) was created to clarify roles and responsibilities pertaining to food safety, to reduce overlap and duplication, and to improve

delivery of services, federal/provincial harmonization and cooperation, and reporting to Parliament. In CFIA, Canada consolidated all federally mandated food, plant, and animal inspection and quarantine services formerly provided by the Departments of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Health Canada (HC), Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Industry Canada. Prior to this reorganization, the government carried out extensive outreach with all stakeholders, including foreign countries.

Under the CFIA Act, the Minister of Health (HC) establishes standards and policies governing the safety and nutritional quality of all food sold in Canada. HC is responsible for risk assessment pertaining to food safety with regard to human health. HC identifies and prioritizes issues based on scientific evaluation of the likelihood that a specific adverse health effect will occur and carries out foodborne illness surveillance, providing a system for early detection and warning and a basis for evaluating control strategies. HC also was given authority to assess the effectiveness of CFIA activities, thus providing checks and balances on the food safety system to ensure that assessed risks are being managed appropriately.

CFIA, reporting to the Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food, is responsible for enforcing the policies and standards established by HC. It is responsible for both risk assessment and management in the areas of animal health and plant protection. CFIA was also established as a corporate structure with a president at its head. All import and international trade activities pertaining to foods fall under CFIA. Part of the assessment performed in establishing CFIA was to determine which activities benefited the public good and thus would be supported through tax dollars and which should be cost-recovered as they benefited industry. At present, the food safety and quality programs for the Meat Inspection Act, Fish Inspection Act, and Canada Agricultural Products Act are subject to user fees, but only a small percentage of CFIA’s overall budget is cost recovered (CFIA, 2009a). It should be noted that Canadian provinces play a large role in ensuring the safety of food products within their jurisdictions, but not in the regulation of food imports/exports.

There are a number of significant differences between the U.S. and Canadian food import systems that should be noted, although most of the mechanisms and goals are quite similar. Canada conducts “monitoring sampling,” that is, “unbiased sampling” to “assess human dietary exposure, perform risk assessments, monitor trends, identify potential problems and at-risk population groups, set standards and guidelines, and evaluate the effectiveness of programs.” It also conducts “directed sampling” or “biased sampling,” that is, “directed at targeted sample populations … to investigate and verify any suspected problems of potential health risk suggested by the monitoring program.” Although directed sampling can lead to detention of a product, products that are tested under monitoring

and directed sampling are not required to be held pending analysis (CFIA, 2005). When violations are found during monitoring sampling, importers must demonstrate that subsequent shipments from that source meet standards (CFIA, 2008). “Compliance testing is directed at specific samples suspected of not complying with specific regulations. … The product is usually detained until the test results indicate the appropriate disposition” (CFIA, 2005). The FDA’s surveillance sampling is similar to Canada’s monitoring sampling; however, products must be held pending sampling results. Canada also carries out special surveys, blitzes, and legal sampling, the latter applying when legal action is anticipated to ensure appropriate sampling and testing procedures.

Canada and the FDA have taken some different approaches toward violative residues. Canada generally establishes finite limits for situations in which there is no official maximum residue limit/tolerance for a particular chemical residue or contaminant. For example, the FDA generally has taken action on pesticide residues based on the level at which the chemical can be reliably identified and measured, which evolving technologies may drive to ever lower levels. With other contaminants, Canada and the FDA usually follow a similar risk-based approach. Another difference in Canada’s program is that seafood importers are licensed. Canada provides educational sessions for fish import license holders to help them understand Canadian requirements and license holder responsibilities (CFIA, 2009b). If violations are repeatedly found with an importer’s products, the license can be revoked (CFIA, 2009c). Finally, for any type of product, Canada generally does not move, even when multiple violations are found, to countrywide detention, but continues to place individual importers/firms with violative products on a list requiring that their products be tested before they can be imported (CFIA, 2009d).

EU

The EU also separated risk assessment from risk management when the European Commission established its food safety structure. The U.S. food safety regime, including the FDA, was one of the country systems studied and visited when the European Commission’s system was developed. The resulting White Paper on Food Safety (European Commission, 2000) sets forth a “farm to table” approach. Simply described, the European Commission (in which food falls under the Directorate General for Health and Consumers, also known as DG SANCO) ensures that food safety legislation established by the Council of the European Union (Council) and the European Parliament (the two legislative bodies in the EU) is transposed into national law and properly implemented. Each member state must incorporate European Commission food rules and standards into its national

legislation to ensure consistency and effectiveness in regulating food safety throughout the 27 Member States. The Member States are the operational units of the food safety program. The Commission’s Food and Veterinary Office (FVO) (located in Grange, Ireland) audits each Member State’s programs on a schedule. The independent European Food Safety Authority has the responsibility for risk assessment, including compiling and assessing the scientific basis underpinning the EU food safety legislation.

The EU has a list of high-risk food products, generally products of animal origin, including meat and poultry, game meats, gelatin, dairy, seafood, pet foods, and honey (Agreement on Sanitary Measures, 1998). For these products, the Commission requires that all importing countries have a system in place that provides the same level of safety as that for foods produced within the EU. DG SANCO has equivalence agreements with other countries, including the United States, for one or more of these products (DG SANCO, 2009a). For these products, the EU also requires a minimum number of physical checks per annum, just as is required for EU Member States, as well as import certificates on a consignment-by-consignment basis from the exporting countries. For all foods in this high-risk category, each consignment must undergo an official veterinary check at the entry post. Entry posts are limited in number to enable these inspections. Just as the FVO conducts periodic audits of each Member State’s program, it also audits other countries’ programs to ensure that the level of food protection is being upheld by all parties producing food for consumption within the EU (DG SANCO, 2009b).

Australia and New Zealand

Australia’s Imported Food Inspection Scheme is run jointly by the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service (AQIS) and Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ). The Imported Food Control Act of 1992 provides the legal basis for the program. The program is risk-based, with FSANZ advising on food risk assessment policy, as well as food inspection and testing under its Food Standards Code, and AQIS staff having operational responsibility for inspection and sampling. FSANZ classifies all foods into one of three inspection categories, which determines their inspection frequency: risk, active surveillance, or random surveillance. Foods in the risk category pose a medium or high risk to public health. These foods require 100 percent referral to AQIS from Australia Customs for inspection. Shipments tested are held pending analytical results. From this point, inspection frequency is based on a particular producer’s performance. The first 5 shipments from a producer are inspected, and if these shipments are in compliance, the inspection frequency is reduced to 1 in 5, with 1 shipment being inspected and the other 4 released with no inspection, for a total

of 20 shipments. Thereafter, if all inspections are cleared, the inspection rate is reduced to 1 in 20 shipments. A single violation can cause the testing rate to revert to the 100 percent level.

For foods in the active surveillance category, 10 percent of shipments from each supplying country are referred to AQIS for inspection, and the products are released after sampling. The test results are analyzed periodically by FSANZ to determine whether the category classification is still appropriate or should be changed. For foods in the random surveillance category, 5 percent of all consignments are inspected, and the products are released after sampling. If an active or random surveillance food does not comply with the Food Standards Code, a holding order may be issued against the foreign supplier, meaning that the food has been raised to the risk inspection category or 100 percent inspections.

Referral for AQIS inspection does not mean that all shipments are tested. Inspectors examine all referred foods visually, looking for labeling and packaging defects and indications of contamination. Samples may also be taken to test for pathogens, chemical residues and contaminants, additives, and adherence to compositional requirements (FSANZ, 2003).

All inspection and laboratory work is cost recovered and charged to the importers, to whom the government has given the responsibility of meeting country requirements. AQIS is required to recover 100 percent of the cost of running its inspection system through charging fees. In the case of low-risk foods, because it would be inequitable to charge only importers who happened to have their products tested under the 5 percent sampling rate, all importers pay a low, uniform inspection/testing fee for every shipment entered (AQIS, 2008). Each importer must also obtain a permit to import food. When importers apply for the permit, the government uses that opportunity to ensure that the importer knows the food safety and animal and plant health requirements of the country. All countries must meet the FSANZ standards.

Australia rarely requires export certificates. The exception is when the certificate requirement is being used as a tool to deal with a specific problem. In such cases, the issue is usually one of animal health rather than food safety.

Unlike Australia, New Zealand requires official certificates from exporting countries. Consignment-by-consignment certificates are seen as a useful tool in the regulation of imports for a number of reasons. First, a certificate gives the importing country a handle on the composition of the shipment at export, so it is useful in identifying the consignment and ensuring that it is not confused with another shipment on import. The description of the product on export also helps in indicating whether the product was tampered with during shipment, and thus is useful in monitoring security on import. The attestations in the certificate are helpful in ensuring that

the exporting party and its government are aware of and complying with New Zealand’s requirements. New Zealand sees certificates as quite useful in tracing shipments when something goes wrong as, for example, in the Chinese melamine case.

INTERNATIONAL FOOD STANDARDS: CODEX ALIMENTARIUS

The Codex Alimentarius Commission is an international body comprised of governments as its members. Its dual role in developing international food standards and guidance is to (1) protect the health of consumers and (2) ensure fair trade practices in food trade (FAO/WHO, 2008). The Codex was formed in 1962 by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Its Secretariat is housed at FAO in Rome, and it has more than 180 member governments. Since its inception, Codex standards have been utilized as voluntary standards that countries may choose to incorporate into national legislation. The standards are based on evaluations of scientific data and other necessary information. They address food safety hygiene, analytical methodologies, maximum limits for residues of pesticides and animal drugs in foods, nutrition issues, food labeling, limits for contaminants, product identity standards, and food inspection and certification, among other things.

Since the advent of WTO in 1995, Codex standards and guidance have served as reference standards in trade challenges before WTO. The SPS Agreement specifically recognizes the Codex Alimentarius Commission (WTO, 1995). The Codex standards can be used in challenges involving foods under the WTO Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) Agreement as well. The SPS Agreement requires countries to base their national measures on international standards, guidelines, and recommendations, or provide the scientific basis for doing otherwise. Countries with limited resources can rely on Codex food safety standards instead of developing their own standards to protect public health and facilitate trade.

The FDA has participated in Codex Alimentarius since its inception and devotes a significant amount of resources to Codex work. The FDA does not have a procedure to adopt Codex standards and texts as national requirements. However, in partnership with the U.S. Codex Office (located in FSIS, under the Office of the Under Secretary for Food Safety in USDA) and the other federal agencies engaged in Codex activities (USDA agencies, the Departments of State and Commerce, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, and EPA), the FDA endeavors to ensure that all Codex standards, guidance, and other texts are consistent with U.S. national measures.

WTO: FOOD SAFETY AND TRADE OBLIGATIONS

In 1994, the Uruguay Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations concluded with the Ministerial Meeting, where countries signed off on the Final Act of the Uruguay Round and the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the WTO. The SPS and TBT Agreements are the two WTO agreements that focus on nontariff trade barriers, and both can apply to foods in different respects. The U.S. Congress enacted all the WTO agreements as U.S. law in the Uruguay Round Agreements Act of December 1994, just prior to the January 1, 1995, the date on which the agreements entered into force.

The FDA participated actively on the U.S. negotiating team for the Uruguay Round negotiations, especially on the SPS negotiations. The eventual text provided a balance between preserving a country’s sovereign right to protect its citizens from public health hazards in imported food (among other things) and enabling agricultural trade to flow. Generally, under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the SPS Agreement, WTO Members are not allowed to discriminate arbitrarily or unjustifiably among imports from WTO Members, meaning that all Members should be treated equally with respect to trade; nor can Members give less favorable treatment to a WTO Member’s goods than they do to their own; unless there is a reason based in science (recognizing, however, that each Member’s country has the right to set its own appropriate level of protection). These principles are called Most Favored Nation Treatment (WTO, 2009a) and National Treatment, respectively (WTO, 2009a).

For its part in the negotiations, the FDA wanted to ensure that the trade agreement would not impinge on its ability to protect public health, and it was successful in this regard. For purposes of this appendix, only sanitary measures are discussed, as phytosanitary, or plant health, measures are not at issue. The SPS Agreement states the right of WTO Members to establish sanitary measures to protect human or animal life or health, but places limits on this right. Some of these limits, or obligations, are mentioned below. A WTO Member or Members may bring a challenge against other Members they believe have violated these legally binding obligations. Such issues may first be raised informally at an SPS committee meeting in Geneva, generally held three times a year. A country may also raise a complaint formally and enter into the dispute settlement process, which may result in the establishment of a dispute settlement panel to assess the facts of the case and make a ruling.

It is useful to understand what exactly is a sanitary measure under the SPS Agreement. The definitions in Annex A indicate that they may include the following:

Any measure applied …

(b) to protect human or animal life or health within the territory of the Member from risks arising from additives, contaminants, toxins or disease-causing organisms in foods, beverages or feedstuffs;

(c) to protect human life or health within the territory of the Member from risks arising from diseases carried by animals, plants or products thereof. (WTO, 1995)

Measures can include laws and regulations, among other things, as well as operational measures, such as testing methods, sampling procedures, and methods of risk assessment.

A few of the SPS Agreement obligations are important to mention here (WTO, 1995). For example, under Article 2, WTO Members must ensure that measures are both applied only to the extent necessary to protect health and based on scientific principles. Members must ensure that their measures do not arbitrarily or unjustifiably discriminate between other Member States in which similar conditions prevail, including between their own territory and that of other Members.

Under Article 3, as mentioned in the previous section, Members must base their measures on international standards, guidelines, or recommendations, where they exist. Sanitary measures that conform to international standards, guidelines, or recommendations are deemed necessary to protect life or health and are presumed to be consistent with the SPS Agreement and GATT 1994. Thus, Codex standards become a “safe harbor” in the event of a challenge under the SPS Agreement. However, Members can still set sanitary measures that provide a higher level of protection if they are scientifically justified and based on the country’s chosen level of protection.

Under Article 4, on equivalence, a Member is obligated to accept the sanitary measures of other Members as equivalent if the exporting Member objectively demonstrates to the importing Member that its measures achieve the importing Member’s appropriate level of sanitary protection.

Under Article 5, on assessing risk and determining a country’s appropriate level of protection, WTO Members must ensure that their sanitary measures are based on an assessment, as appropriate to the circumstances, of the risks to life or health, taking into account relevant scientific evidence, among other specified considerations, including economic factors.

Also included are other provisions pertaining to transparency in establishing measures and the rights and obligations of countries that have premarket approval systems for such things as veterinary drugs, pesticides, and food additives.

With regard to foods, the TBT Agreement applies to the extent that the issue, such as food labeling requirements not established to protect human or animal life or health, is not covered in the SPS Agreement. The TBT

Agreement is a wide-ranging agreement dealing with all kinds of nontariff trade barriers for all sorts of products, while the SPS Agreement is the primary agreement focused on national measures to protect agricultural and forestry products and food.

PRACTICAL CHALLENGES IN MEETING THE FDA’S IMPORTED FOOD PROGRAM OBJECTIVES

The goal of any imported food program is ensuring the safety of foods for consumption by the domestic population. The FDA has done a good job in achieving this goal, but there are a number of areas in which it might do better. This section explores some of these areas.

Stakeholder Buy-In

Margaret Hamburg, in her first testimony as FDA Commissioner, said, “A precondition for health is having access to safe food.” She further stated, “A coalition of consumer groups is fighting for improvements in the food safety system so that more families do not have to suffer tragic consequences from foodborne disease. I am impressed that major sectors in the food industry also support and are advocating for fundamental change” (Hamburg, 2009).

It is essential that stakeholders understand and have buy-in and input into the FDA’s imported food program to enable a strong, workable program; to establish incentives for compliance with requirements; and to promote common ground and backing for the program. The public, industry, and congressional dialogue that has taken place over the past few years as the FDA has lost almost a third of its food program resources is a healthy process and one that has helped in clarifying the reasons why the FDA’s food safety program is important in both the domestic and global contexts. The current food safety bills in Congress are evidence that this dialogue process works. The FDA needs to do more to improve understanding of the issues it faces in promoting and regulating imported food safety, its import program objectives, and the reasoning behind these objectives with all its stakeholders, including other federal agencies, the Congress, foreign nations, states, and the general public. This can be done through dialogue, public meetings, brochures on the FDA’s program and accomplishments, and other outreach efforts.

Teamwork, Clear Objectives, and Consonant Implementation

Because a number of offices in FDA headquarters and the field take part in establishing the objectives of the imported food program, it is important

that all these offices understand the various factors to be considered in setting up the program, including laws, resources, available mechanisms to ensure food safety, the global context of international trade agreement obligations, and international standards and guidance that bear on the operation of the program. It is imperative that the program and its policy staff that chart its overall objectives operate as a team with the offices that implement the program. Too often there have been conflicts in priorities or misunderstandings regarding program objectives that have hampered optimal achievement of these objectives.

For example, despite the FDA’s goal of protecting public health from unsafe residues of pesticides in imported foods, the parallel goal of detecting as many violative shipments as possible led field offices in the past to oversample imported spices that often had violative residues. Sampling food products with higher per capita consumption rates might have provided greater public health protection, but the program had strong incentives to find violative products, and spices offered greater opportunity in this regard. Now sampling instructions for this program clearly state that only commodities of dietary importance should ordinarily be sampled (FDA, 2006).9 These types of situations can easily be avoided by (1) establishing clear import program objectives, (2) ensuring that the spirit and rationale behind those objectives are well understood by field personnel, and (3) tracking the program accomplishments throughout the year to see whether adjustments need to be made to achieve the objectives.

Another example involving pesticides could provide a model for improving program design and implementation for imported foods. In the 1980s, FDA consumer surveys indicated that U.S. consumers saw pesticide residues as their top food safety concern. In response, the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) and CFSAN decided to form Pesticide Coordination Teams (PCTs) in each district office, comprised of at least one representative from the laboratory, investigational, and compliance branches of the field office. These teams met regularly to coordinate and track their pesticide monitoring and compliance activities. Moreover, all the teams participated in regular conference calls with the headquarters’ ORA and CFSAN program staffs, and often EPA staff, to be briefed on the latest pesticide issues, congressional hearings, U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports, press and consumer group reports, analytical improvements, or whatever brought greater understanding of why their work was so important to the

|

9 |

Pesticides and Industrial Chemicals in Domestic and Imported Foods FY 06/07/08 (7304.004), Part III, “Inspectional General Sampling Instructions”: “Collect samples of commodities of dietary importance identified in Attachment B. Do not sample products such as parsley and spices that have little impact on total dietary intakes. Monitoring of these types of food will be directed by headquarters initiated surveys as needed.” |

U.S. consumer. All teams came together annually at a PCT meeting to compare notes, give presentations, and troubleshoot. The headquarters–field and field–field network in this program area was invaluable to the smooth and responsive operation of the program, which produced a full-color public report annually that often went through several printings because the public demand for it was so great. Although the public health importance of pesticide residues in the food supply has diminished—partly because of new, more protective pesticide legislation—the FDA’s teamwork in giving this program the coordination needed at the time helped EPA and Congress obtain the data and knowledge required to develop the much-needed legislation.

Potential Use of Third-Party Certification

As the FDA’s imported food program encounters a vast variety of foods from a broad spectrum of countries, companies, and importers, the challenges in ensuring imported food safety are considerable. The agency must have available tools that are best suited to the circumstances. One tool the FDA has placed on the table is third-party certification (see Chapter 8). This would involve the FDA’s accrediting third parties to certify that its food safety requirements are being met. Currently, such certification is taking place on a private, commercial basis. In these cases, private standards, including end-product standards and production processes, are being established by a number of bodies. Developing countries have raised concerns to WTO and Codex regarding the use of private standards (Henson and Humphrey, 2009; WTO, 2009b), with the overriding concern that certification is very expensive and cost-prohibitive to small growers. Therefore, third-party certification may be useful only in limited situations where firms or governments can afford or choose to utilize it. Nevertheless, third-party certification can be a useful tool for gaining confidence in a country’s exports when food safety problems have been found, and in other cases, it may enable the agency to shift enforcement resources to where they will do the most good.

Sampling: Surveillance, Compliance, and Hold and Test

Most of the sampling done under the FDA’s imported food program is surveillance sampling. This means the agency does not have reason to believe the particular shipment will be violative. Compliance sampling generally occurs after a problem has been found. Samples are taken at the port of entry and are sent to a servicing laboratory for analysis. The shipment chosen for sampling, under 21 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 1.90, must be held intact until laboratory results are available and a decision can

be made on disposition of the shipment, that is, whether the consignment can be released into commerce or should be refused entry.

Surveillance sampling is done to gather information, to detect food safety problems, and to identify a violative shipment before it enters U.S. commerce. Other developed countries that carry out surveillance sampling of foods generally utilize such sampling to detect problems so they can act to stop future shipments of products that are found to be unsafe or misbranded. They allow the shipments that are randomly sampled to be distributed as they have no reason to hold them. This approach enables a more efficient sampling/analysis program with more sample throughput in the laboratory and more product coverage, but it also opens up the possibility for fault finding by political bodies and the public when a significant safety problem is uncovered. In practice, other countries say this rarely occurs and has not hampered their food protection safety net.

Inspection of Foreign Food Facilities

The FDA’s inspection of foreign facilities with any regularity is impossible given that there are 200,000 such firms registered (Taylor, 2009). For this reason, it may be more appropriate for foreign facility inspections to be reserved for situations in which food safety problems have been detected in products from a facility. Especially given the high cost of foreign inspections, the FDA has recently stated (Taylor, 2009) that foreign inspections may not result in the best use of its resources, so it appears that the agency may be moving in that direction. A tool to obviate the need for individual foreign firm inspections is the recent guidance for Accredited Third Party Certification of firms and the FDA’s recognition through auditing of the certifiers. This tool could provide increased confidence in particular firms, and the resulting data could then be fed into PREDICT (discussed below).

Incentives to Export Safe Food

There are a number of ways to encourage foreign companies to export safe food that could be incorporated into the FDA’s imported food program. It has already been mentioned that the FDA could conduct more outreach to countries. The agency could also require import certificates attesting to food safety that in effect would put the foreign facility on notice that it needs to be aware of the safety status of food it exports to the United States. Licensing importers (or registering them as proposed in HR2749; see below) could be coupled with providing information and outreach to importers that they could convey to the food businesses they are servicing.

RECENT EFFORTS TO IMPROVE IMPORTED FOOD SAFETY

PREDICT

PREDICT is an electronic import screening tool that will automate many of the decisions currently made by import entry reviewers, utilize intelligence from numerous sources to guide automated decision making on the potential risk posed by imported food, and expedite the entry of more products that are not selected for examination. It will replace the admissibility screening portion of the FDA’s existing electronic system (OASIS) for processing import entries.

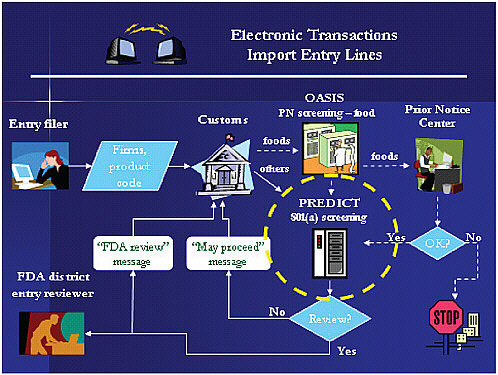

PREDICT will apply to shipments of all products under FDA jurisdiction, not just foods, and will be used for both imported and domestic products. The focus here, however, is only on PREDICT as it applies to foods imported into the United States. This system holds great promise for enabling the use of almost any intelligence received and applying that intelligence in writing risk rules to establish a score for the particular entry line and importer. Such intelligence could include information pertaining to recalls, registration of low-acid canned food processes, agreements with other countries, data provided by governments on monitoring of their own products, information on government or third-party certification of facilities, and information from import certificates. Pilot testing for PREDICT began in June 2007 and was successful based on the evaluation criteria at the time. Now that user acceptance testing has been completed, PREDICT is expected to be beta tested in Los Angeles District in September 2009 and rolled out on a district-by-district basis thereafter.

The current OASIS is the only system in the federal government that exchanges import admissibility data with CBP in real time (ORA, 2009). OASIS receives data on products under FDA jurisdiction from CBP. It then electronically screens entry lines based on certain criteria and generates notices regarding admissibility decisions. OASIS will be supplanted by PREDICT, which has the capability and flexibility to mine data sources and integrate a vast amount of information in arriving at a risk score that can be used to decide whether an entry line may proceed into commerce or should be more closely reviewed. Thus, food entry data will flow from (1) the entry filer (importer, exporter, or broker); to (2) the CBP database; to (3) OASIS for prior notice (bioterrorism screening, which is done on 100 percent of entry lines); and then either to (4) the Prior Notice Center for review if, for example, the entry has no registration number or affirmation of compliance, or (5) straight to PREDICT for admissibility screening. Figure E-3 shows the process (ORA, 2009). The Prior Notice Center can decide to detain the shipment based on terrorism criteria or can release the entry line back into PREDICT admissibility screening. If PREDICT scoring rules determine that

FIGURE E-3 Electronic transactions for import entry lines.

NOTE: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration, OASIS = Operational and Administrative System for Import Support, PN = prior notice, PREDICT = Predictive Risk-Based Evaluation for Dynamic Import Compliance Targeting.

SOURCE: ORA, 2009.

the product may proceed into commerce, then that information is supplied to CBP. Otherwise, PREDICT sends the entry line to an FDA district entry reviewer, with results also being communicated automatically to CBP. The district entry reviewer then has the option to request additional information from the importer to make an admissibility decision, examine the product in the field, collect a sample for analysis, detain the product without a physical exam, or allow it to proceed into commerce.

PREDICT will utilize automated data mining and pattern discovery, open-source intelligence such as news reports, and existing CFSAN databases, including low-acid canned food scheduled processes and registration, to make admissibility decisions. For example, if a new food product is coming from a country, or if a usual product is valued at a significantly diminished amount or is shipped during a different time of year, the entry line may receive a higher score for review because the pattern is different from the usual. News reports of typhoons or hurricanes with significant environ-

mental damage may be added to the PREDICT rules for a country to flag reviews of the country’s food products. Similarly, if a country is willing to provide the FDA with data on its domestic food testing programs and if the FDA finds the data compelling, the agency can create a rule in PREDICT that reduces the risk score associated with the information provided by the country. The rule created will provide the entry reviewer with the reason for the reduction in score. On the other hand, if a trusted country shares its findings on illegal drugs being found in imported fish from particular countries, that information can be utilized as intelligence that may lead to flagging fish shipments from those countries. Firms that have been inspected by accredited third-party certifiers and found to produce products in compliance with U.S. food safety requirements can also be given a score that reduces the risk associated with the products.

PREDICT will work by scoring each entry line on the basis of risk factors and surveillance requirements. The pilot testing on a small sample of 32,696 lines of seafood entering at five ports within the Los Angeles District found that PREDICT was better than OASIS in predicting violations for field exams and sample analyses (ORA, 2009). It also enabled a higher “may proceed” rate—39.1 percent versus 5.7 percent—by utilizing the wide range of intelligence data entered into the PREDICT system for the products. This more accurate prediction of violations and “may proceeds” should reduce workload for the FDA reviewers as well.

PREDICT and OASIS are both part of the Mission Activity Reporting Compliance System (MARCS), which is the overall integration system for a number of interfaceable databases. This is significant because for all the systems to work together, they must have high-quality, accurate data entered. This has been a problem, although inaccurate data entry may now cause PREDICT to flag an entry for review. Importers have been advised of this fact and the fact that their product entries may suffer if data mistakes are made. Another issue with PREDICT is the CBP Manufacturer Identification (MID) system. In the past, manufacturers have provided multiple, inconsistent MIDs for the same foreign facility (ORA, 2009). PREDICT will recognize each MID as a separate facility, and a new MID/facility may be flagged and have a higher risk score. To correct this problem, there are plans to utilize a unique, reproducible identifier for each facility. Nevertheless, importers will need to work closely with filers to ensure data quality, as poor-quality or missing data will increase the risk scores for entry lines. Filers’ data error rates will be available to the public through FOIA.

The Import Trade Auxiliary Communications System is also part of the MARCS system and will interface with OASIS and PREDICT. It is an Internet portal for entry filers. The importance of this interface cannot be overemphasized as entry filers will have instant access to information on the status of their entries. At present, importers must phone FDA district offices

and talk to a person to determine whether a product has been released or whether the agency is waiting for them to provide further information. This interface will also allow filers to submit additional information electronically. Therefore, this system, which is also being beta tested in Los Angeles, has the potential to streamline communications and save resources and effort for FDA field staff and importers alike.

FDA data systems have never had the flexibility to utilize all the information that can affect whether a particular shipment should be examined in some manner. Also important is whether safe products can move unimpeded and without deterioration through trade channels. As better intelligence is generated and received through multiple sources, PREDICT holds the promise of being able to manage field resources and direct them to where they can do the most good in protecting consumers from unsafe products. Achieving this goal, however, is dependent on the decisions and information utilized in setting the rules for PREDICT, and these decisions and rules will surely be the subject of future debate. It is important, however, that in developing the PREDICT criteria, the emphasis be on public health criteria in deciding on admissibility. Given the number and volume of food shipments to the United States and the FDA resources needed to examine them, the criteria should focus on whether consumers are significantly at risk, not on whether examination/sampling of a product will simply result in a violation that may be of negligible health concern. As efficient use of public health resources is one of the purposes of PREDICT, it is hoped that this system can live up to its full promise.

Food Safety Working Group

On July 7, 2009, the Food Safety Working Group (FSWG), established by President Obama, issued its key findings on how to upgrade the nation’s food safety system for the 21st century (FSWG, 2009). The FSWG recommended a new public health–focused approach to food safety based on three core principles: (1) prioritizing prevention, (2) strengthening surveillance and enforcement, and (3) improving response and recovery. Although the FSWG’s initial key findings say little that pertain to the FDA’s imported food program, it is understood that the full report, yet to be released, may contain such recommendations.

Food Protection Plan and Import Safety Action Plan

Both of these documents were produced under the previous administration, and while they have not explicitly been supplanted, the work of the cabinet-level FSWG and work on food safety legislative proposals (see below) have generally taken priority. Many of the recommendations of the

Food Protection Plan (FDA, 2007) and the Import Safety Action Plan (Interagency Working Group on Import Safety, 2007) pertaining to imported foods have, according to FDA contacts, been incorporated or addressed in the FSWG report, although until the full report is released by the White House, this cannot be confirmed.

Food Safety Legislation

Several pieces of food safety legislation have been proposed in the current Congress, including S510, HR875, HR759, and HR1332. On August 3, 2009, a comprehensive bill was passed by the House of Representatives and referred to the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. This legislative proposal, HR2749, pertains to the FDA’s overall food safety program but focuses primarily on the domestic portions of the program (U.S. sovereignty cannot easily extend into the territories of other countries). Nevertheless, it would provide for some major and potent new authorities in the food import and export areas (see also Appendix D):

-

Registration of facilities—Under section 101, all facilities, domestic or foreign, that produce, pack, or hold food for consumption in, or for export from, the United States must submit an annual registration and pay a registration fee, which is set at $500 for 2010 but may be revised thereafter. Registration may be suspended if the registrant is found to have violations that could result in serious adverse health consequences or cancelled if registration is not updated annually or inaccurate information is submitted. This fee certainly would not be adequate to sustain the FDA’s imported food program but would put registrants on notice that they need to avoid violations of U.S. law or risk losing their registration and no longer be able to export to the United States. Imported food will be considered “misbranded” if it comes from an unregistered facility. The bill authorizes collection of fees only until 2014.

-

HACCP requirement for all registered firms—Under section 102, all facilities that are required to be registered annually, whether domestic or foreign, must have a food safety plan with a full HACCP program in place. The FDA will have to issue guidance or promulgate regulations to establish science-based standards. The bill explicitly states that international HACCP standards will be reviewed in issuing the guidance or regulations to ensure consistency.

-

Inspections based on risk—Each registered facility must be inspected. Foreign facilities can be inspected by an agency or representative of a country recognized by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The frequency of inspections

-

is based on whether the facility is Category 1, high risk (inspect every 6–12 months); Category 2, low risk (inspect every 18–3 months); or Category 3, holds food (inspect every 3 years). A facility’s category depends on the type of food, its compliance history, whether it is “certified” by a quality entity, and other relevant factors. This provision requires notice and comment before a categorization is established or modified, which will be difficult and extremely resource intensive to implement, especially for foreign facilities. There is also a requirement to provide an annual report and a 3-year assessment to Congress on the costs and success of the program.

-

Finished product testing from Category 1 facilities—Finished product test results must be provided by the owner, operator, or agent of each Category 1 facility (beginning after public notice/comment, pilot projects, and a feasibility study to be completed within 2 years). The firm must also have a food defense plan to prevent contamination throughout the supply chain. The testing must be done in accordance with science-based performance standards, to be established under section 103. Every 2 years, HHS will review and evaluate epidemiological data to identify the most significant foodborne hazards and apply performance standards to foods/food classes for compliance with these standards.

-

Mandatory Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs)—Under section 104, there is a new provision for a determination of adulteration under the FDCA whereby raw produce not grown, harvested, processed, packed, sorted, transported, or stored under required standards can be considered adulterated under the law. The Secretary of HHS will determine for which foods mandatory standards/GAPs are necessary.

-

Records access—Each person who manufactures, processes, packs, or holds an article of food in the United States or for importation into the United States must give inspectors access to records, including the food safety plan. This provision does not generally apply to farms, but in fact does if the food is a fruit, vegetable, nut, or fungus. Records must be retained for 3 years. Restaurants must keep records of suppliers only, so the current restaurant exclusion is modified. The most important change with this provision is that the FDA does not have to demonstrate that the food hazard poses a serious threat to life. Access to records can simply bear on whether such food is adulterated, misbranded, or otherwise in violation of the FDCA.

-

Traceability—In section 107, the FDA is asked to hold two public meetings before putting this provision into effect, as this subject

-

has stirred great controversy in the past. The provision foresees maintenance of a full pedigree of origin and previous distribution of the food. The provision applies to food within or for importation into the United States.

-

Certification and accreditation—Within 3 years after the date of enactment of the legislation, if a shipment requires but lacks certification of compliance, it will be considered misbranded in violation of section 801(q) and will be refused admission into U.S. commerce. Section 801(q) imposes an additional condition for admission of foods whereby a qualified certifying entity must provide certification that the food complies with the FDCA. Thus, if the Secretary has found that a food from a particular country, territory, or region is not subject to adequate government controls to ensure that it is safe and that certification would assist in this regard, a certificate of compliance can be required. The risk concern must be based on science. A qualified certifying entity is defined as a government or other entity recognized by the Secretary.

-

Disclosure of information—Section 112 allows for disclosure of non-public information to bodies if they can protect the information.

-

Importation facilitated—Under section 113, a program can be established, in coordination with CBP, to facilitate the movement of food through the importation process if the importer (1) verifies that each facility is in compliance with food safety and security guidelines, (2) ensures that appropriate controls are in place through the supply chain, and (3) provides supporting information to the Secretary.

-

Country-of-origin labeling for all foods—Foods will be considered misbranded under the law if (1) labeling of processed food fails to identify the country in which final processing occurred, or (2) for nonprocessed food, if the country of origin of the food is not given.

-

Export certificates—While not part of the import program, CFSAN currently issues thousands of official export certificates annually since some countries demand such certificates as a condition for entry of imported foods. Section 203 simply adds foods to section 801(e)(4) and allows the FDA to collect fees in appropriate amounts to support the issuance of certificates.

-

Registration for commercial importers of food—Section 204 considers a product misbranded if the importer is not registered. Maintenance of registration is conditioned on compliance with Good Importer Practices (GIPs) (in January 2009, cross-cutting GIP guidance was published; this section anticipates regulations rather than guidance). The importer should have information about the

-