2

The Food Safety System: Context and Current Status

Since humans began farming, agriculture has evolved rapidly, with pervasive effects on society. An example is the industrialization of food production in the twentieth century, which, among other things, dramatically changed perceptions and behaviors related to food (Hennessy et al., 2003). While this revolution in food production resulted in great benefits to today’s consumers and the ability to feed a growing population, it also resulted in unanticipated foodborne risks. Regulatory agencies responsible for food safety thus are challenged not only to respond to current issues, but also to articulate a vision of food safety that anticipates future risks. This chapter sets the stage for the more detailed assessments, findings, and recommendations that follow by reviewing some of the developments that have contributed to the context for food safety in the United States and by providing an overview of the current U.S. food safety system.

A CHANGING WORLD

The Institute of Medicine (IOM)/National Research Council (NRC) report Ensuring Safe Food: From Production to Consumption (IOM/NRC, 1998) identifies a number of developments with implications for food safety, including (1) emerging pathogens, (2) the trend toward the consumption of more fresh produce, (3) the trend toward eating more meals away from home, and (4) changing demographics, with a greater proportion of the population being immunocompromised or otherwise at increase risk of foodborne illness. These developments continue to be important today, but many others affecting food safety have occurred in the decade since that

report was published. Together, these developments contribute to the current context for food safety in the United States, which is characterized by a number of features that must inform any assessment of the food safety system. These include changes in the food production landscape, climate change, changing consumer perceptions and behaviors, globalization and increased food importation, the role of labor–management relations and workplace safety, heightened concern about bioterrorism, increased levels of pollution in the environment, and the signing of international trade agreements.

Changes in the Food Production Landscape

In addition to constant changes in food production and substantial growth in the number of food facilities (the number regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA] grew by 10 percent between 2003 and 2007 [GAO, 2008a]), the food and agriculture sector has experienced widespread integration and consolidation in recent years. For example, the consolidation of supermarkets has changed the retail grocery landscape in the United States, leading to the dominance of the industry by a small number of large companies. Apart from consequences for the market share of small retailers, the greater dependence of manufacturers on this limited number of retailers for sales volume gives these companies significant leverage to bargain for lower prices and demand safety standards. The result has been an increased tendency to establish private standards, which has changed the enterprise of food safety (Henson and Humphrey, 2009).

For example, large retailers and customers established the Food Safety Leadership Council on Farm Produce Standards to develop standards for the growing and harvesting of fresh produce (FSLC, 2007). Another private effort was the Global Food Safety Initiative, created in 2000 to set common benchmarks for different national and industry food safety programs. Its standards, now used widely around the world, require that the food protection practices of manufacturers of food, including produce, meat, fish, poultry, and ready-to-eat products such as frozen pizza and microwave meals, be audited at regular intervals (GFSI, 2007). Farmers, shippers, and processors in the business of producing leafy greens may participate in the California Leafy Greens Marketing Agreement, a private mechanism operating with oversight from the California Department of Food and Agriculture that verifies whether growers are following certain food safety practices (LGMA, 2010). Adoption of these private standards could be seen as an enhancement of food safety; however, private standards can also impose unnecessary burdens if they are not scientifically justified. For example, private standards may result in unnecessarily higher food prices (DeWaal and Plunkett, 2007). Therefore, a close look at such standards is warranted. As an alternative, public standards can be instituted. For example, Tomato

Good Agricultural Practices for tomato farms and Tomato Best Management Practices for tomato packinghouses are the first mandatory produce safety programs in the United States (Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, 2007).

Climate Change

Climate change is doubly relevant to the food enterprise: not only may climate change affect food yields, but food production may contribute to climate change by releasing a substantial amount of greenhouse gases, such as carbon monoxide and nitrogen monoxide (Stern, 2007). Stern (2007), among others, has highlighted serious concerns regarding the effects of climate change on future food security, especially for populations in low-income countries that are already at risk of food insecurity.

Climate change can affect food systems directly, by affecting crop production (e.g., because of changes in rainfall or warmer or cooler temperatures), or indirectly, by changing markets, food prices, and the supply chain infrastructure—although the relative importance of climate change for food security and safety is expected to differ among regions (Gregory et al., 2005). A recent Food and Agriculture Organization paper, Climate Change: Implications for Food Safety (FAO, 2008), identifies the potential impacts of anticipated changes in climate on food safety and its control at all stages of the food chain. The specific food safety issues cited are increased range and incidence of common bacterial foodborne diseases, zoonotic diseases, mycotoxin contamination, biotoxins in fishery products, and environmental contaminants with significance for the food chain. To raise awareness and facilitate international cooperation, the paper also highlights the substantial uncertainty on the effects of climate change and the need for adequate attention to food safety to ensure effective management of the problem.

Changing Consumer Perceptions and Behaviors

With an increasingly global food market, consumer expectations and behaviors with regard to food have changed dramatically over the past hundred years. Consumers have grown to expect a wide variety of foods, including exotic and out-of-season foods. As a result, the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables has increased (IOM/NRC, 1998) and is expected to continue to do so: per capita fruit consumption is predicted to grow in the United States by 5–8 percent by 2020, with a smaller increase predicted for vegetables (Lin, 2004). Additionally, consumers are spending more money on food away from home, which accounted for 48.5 percent of total food dollars, or approximately $565 billion, in 2008 (ERS, 2010).

At the same time, consumer perceptions and behaviors with respect to food safety have also changed significantly. Consumer knowledge about foodborne pathogens, high-risk foods, vulnerable populations, and safe food-handling practices has increased in recent years, although this knowledge is sometimes wrong or incomplete (FSIS, 2002). Recent foodborne illness outbreaks have further increased consumer awareness about food safety; in fact, a majority of consumers believe foodborne illnesses are a serious or very serious worry (FSIS, 2002; Hart Research Associates/Public Opinion Strategies, 2009). Further, recent polls indicate a lack of confidence in the ability of the FDA to protect consumers against food-related threats (Hart Research Associates/Public Opinion Strategies, 2009).

While food producers, processors, and retailers have the primary responsibility for the safety of the food they produce, food preparers also play an important role in preventing foodborne illness. Accordingly, several groups have developed educational messages aimed at teaching safe food-handling behaviors to consumers and other food preparers. The Clean, Separate, Cook, Chill approach, for example, is focused primarily on consumers in the home. However, this initiative has proven to be largely ineffective (Anderson et al., 2004). Several studies have found that, although self-reported use of safe food-handling practices has increased, consumers and other food preparers do not always follow these practices (Redmond and Griffith, 2003; Howells et al., 2008; Abbot et al., 2009). Further, the International Food Information Council Foundation found that many consumers fail to use some important food safety practices; for example, just 50 and 25 percent of consumers, respectively, use a different or freshly cleaned cutting board for each type of food and check the doneness of meat and poultry items with a food thermometer (IFICF, 2009). Several factors have been identified as affecting the adoption of safe food-handling practices, including attitudes, lack of motivation, sociodemographic factors, and cultural beliefs (Medeiros et al., 2004; Patil et al., 2005; Pilling et al., 2008). In addition, the media often promote poor food-handling practices during on-air cooking demonstrations and frequently give misinformation on the subject (Mathiasen et al., 2004). The decline of home economics classes in schools, coupled with the increasing trend to eat out, further contributes to the lack of food safety knowledge. In addition, few medical providers diagnose and report foodborne illness, and fewer yet discuss safe food-handling practices with their patients (Wong et al., 2004; Henao et al., 2005).

Globalization and Increased Food Importation

The expansion and liberalization of international trade in recent decades have resulted in an increase in food imports. By 2005, the volume of imported medical supplies and food had increased seven-fold over that in 1994, and

this trend is expected to continue (Nucci et al., 2008). Among foods, the increase has been especially dramatic in the seafood sector, which the FDA oversees. From 1996 to 2006, the volume of FDA-regulated food imports increased almost four-fold, from 2.8 billion to 10 billion pounds (Nucci et al., 2008). About 230,730 facilities that deal with imported foods are registered with the FDA, including foreign manufacturers, packers, holders, and warehouses (FDA, 2010a). Consequently, there is a growing need for a robust regulatory system that can ensure the safety of food imports. This concern over the safety of imported foods is reflected in the number of congressional hearings on the subject in 2007 and 2008 (GPO, 2010).

Various countries are experimenting with models for regulating food imports (e.g., third-party certification, inspections at the border, country certifications; see Appendix E), but there is no consensus on the best regulatory models. In this environment, the United States is attempting to determine the best model to implement given available resources and the vast amount of imported foods to oversee. For example, in 2007, at the request of the White House, the Interagency Working Group on Import Safety was established. It included, among others, representatives of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the parent agency of the FDA, and the Department of Agriculture (USDA). The working group developed a road map recommending both broad and specific actions that would enhance the safety of all food imports (Interagency Working Group on Import Safety, 2007).

The Role of Labor–Management Relations and Workplace Safety

The crucial role of food employees and employers in food safety cannot be overstated, particularly since food workers have been implicated in the spread of foodborne illness (Todd et al., 2007). When addressing food safety, therefore, it is important to consider the potential role of labor–management relations and workplace conditions. For example, if the labor force responsible for producing food on farms and in factories is inadequately trained or paid, is forced to work under unsafe or unsavory conditions, or is ignored by management when it attempts to express concerns, workers may respond by applying less care in the production, processing, or preparation of food, leading to increased risk for consumers. Some elements of this association may be direct since many human pathogens are easily transmitted to foods via contact with human vehicles, and worker sanitation and hygiene are critical factors in this process. Specifically, ensuring that workers have access to appropriate sanitary facilities, providing adequate sick leave, and making hand washing a critical control point are vital to controlling many hazards in the food supply. For example, if farm laborers in the field are not provided with adequate sanitary facilities, there will be increased opportunity for crop exposure to

infectious agents. And if workers are not given sufficient training for their basic work activities, they are also less likely to be trained in minimizing risks for food products.

Regulation and oversight of all phases of the food supply chain by all levels of government can help enhance food safety by identifying situations in which work procedures need improvement or workers need training. Cooperation between the FDA and labor regulatory agencies such as the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration would appear to warrant exploration.

Heightened Concern About Bioterrorism

Although public health agencies have been concerned about the potential for intentional contamination of food in the past, this concern increased greatly after the events of September 11, 2001. The volume of food animals and commodities, the lack of physical security and robust surveillance systems for food products, and the rapid movement of food products over a broad geographic range and through many hands make the U.S. food supply highly vulnerable to intentional contamination (Kosal and Anderson, 2004). A major activity in response to this threat was the FDA’s establishment, with USDA and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), of a food defense partnership (i.e., sector organization) with all relevant federal, state, local, and industry counterparts (see Appendix D). Various other efforts followed the establishment of this partnership, increasing the responsibilities of all involved and of the FDA in particular. The FDA is engaged in food defense activities to implement new presidential directives and congressional legislation, as well as to educate and communicate with industry, its own staff, and state, local, and foreign counterparts about matters related to food defense. The issue of terrorism-related prioritization of efforts is highly problematic, however, because of the uncertainty concerning the likelihood and nature of an attack (information about which is generally classified). This uncertainty makes comparisons with other risks and justifications for resource allocation and prioritization difficult.

Increased Levels of Pollution in the Environment

An undesirable consequence of the industrialization of agriculture and manufacturing is the release of chemicals to the environment. Not all food pollutants come from industrial processes, however. For example, dioxins and furans are contaminants released unintentionally into the environment as a result of both preindustrial combustion processes (e.g., the combustion of forests or brush) and modern combustion processes (e.g., industrial burn-

ing, landfill fires, structural fires) (IOM/NRC, 2003). Whether exposure to these pollutants has increased over the years depends on the pollutant, and the data needed to assess trends are often lacking (IOM, 2007).

The bioaccumulation of pollutants in the food chain (e.g., methylmercury in seafood) has received a great deal of attention. The pollutants of concern may change over time as manufacturing processes evolve, but those that are persistent in the environment can be a chronic issue for public health and environmental agencies. The growing attention to the problem is due to both increased understanding of bioaccumulation and greater public concern about environmental pollutants in general, both domestically and internationally. The potential long-term effects of these pollutants, coupled with the difficulty of measuring multiple exposures and potential interactions, present a complex problem.

Although the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), not the FDA, is the agency that regulates levels of pollutants in the environment, food commodities are subject to contamination via the environment. Much of the work on collecting and analyzing environmental and toxicological data on food pollutants has already been done by EPA, and EPA’s risk assessments can often be used as the basis for food policy. A recent report, however, found that the national residue program is not accomplishing its mission of monitoring the food supply for harmful residues (USDA, 2010a).

The Signing of International Trade Agreements

In the wake of the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 and the signing of the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, countries are obliged to follow some basic rules in the application of food safety measures and plant and animal regulations. Countries can set their own standards for safety, but those standards must be based on science. The intent is to avoid protectionism on behalf of domestic producers of food and allow for free trade based on competitive principles. Although the obligations of this agreement were not fully understood at first by governments, it is increasingly viewed as a legal document with the same force as domestic law (Carnevale, 2009). In practical terms, this means that unscientific regulations that affect trade could be successfully challenged at WTO.

As an example, the United States and Canada brought to WTO the European Union’s (EU’s) ban on the importation of meat and meat products that had been treated with any of six hormones, which favored EU meat producers and blocked exports from the United States and Canada. The WTO Panel and Appellate Body concluded that the prohibition was not based on scientific evidence, and a settlement was reached (Lugard and

Smart, 2006). Policies of the United States have also been under scrutiny. A recent analysis suggests that foreign food producers may be at a disadvantage when they want to export to the United States because they need to comply with costly requirements under the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002, such as providing prior notice of shipment (GAO, 2004a; Boisen, 2007).1 As the volume of imported foods continues to rise, such international agreements are becoming more important and must be considered in any discussion of enhancing food safety in the United States. (International trade agreements and their influence on food safety oversight and regulations are discussed in detail in Appendix E.)

LIMITS ON FOOD SAFETY

In examining how to improve a food safety system, one must acknowledge that foodborne illness cannot be completely eliminated. Many factors affect the degree of safety that is achievable, some related to the state of science and others to human factors, such as economic considerations and people’s desire to enjoy certain foods whose safety cannot be ensured (e.g., raw milk). The degree of food safety that is attainable also depends on management and oversight practices, on costs versus benefits, and on such factors as regulatory limits, public perceptions, consumer education and responsibility, and public communication.

It is important to stress that responsibility for food safety falls on everyone, from farmers to consumers. However, the FDA is often held responsible for negative events related to food safety, given that ensuring food safety is part of the agency’s core mission. This focus on the FDA’s responsibilities has grown as such events have become more widespread, garnering increased media attention. Moreover, in recent years, reductions in the incidence of foodborne illness seen in the late 1990s appear to have leveled off (CDC, 2009), and for some pathogens the incidence has recently increased (CDC, 2010). Because many government agencies are responsible for food safety, it is not possible to attribute changes in the rate of foodborne illness to any particular agency. Still, the FDA’s responses to these events have sometimes been less than optimal (Produce Safety Project, 2008).

One limit on the degree of food safety attainable is the fact that to achieve a complete absence of pathogens and other contaminants in food is an unrealistic goal (IOM/NRC, 2003). Although the concept of zero tolerance for a particular pathogen may appear justifiable, it is merely a

regulatory term with little scientific basis. As the IOM/NRC report Scientific Criteria to Ensure Safe Food states: “Scientists are often dismayed by the use of the term [zero tolerance] because they recognize the inability to ensure, in most situations, the complete absence of pathogens and contaminants and the limitations of any feasible sampling plan to check for their total absence” (IOM/NRC, 2003, p. 25). Moreover, most interventions to minimize food hazards have only limited effects in decreasing the prevalence of pathogens, and for some foods, such as those sold raw, few interventions are possible. Recognizing these realities, zero tolerances are viewed as an enforcement tool applied to the most problematic hazards with the goal of communicating that the highest level of public health protection is needed (DeWaal, 2009).

The creativity of those seeking to compromise food safety for profit, the evolution of bacteria to increased virulence, and the inevitability of human errors will continue to challenge regulators, producers, and consumers. As demonstrated by the recent incident in which several brands of pet food were contaminated with melamine, researchers struggle with the question of how to predict, mitigate, and prevent such relatively rare events. The predictability of such events must be taken into account when decisions are made about allocating resources to prevention versus rapid response.

OVERVIEW OF THE CURRENT FOOD SAFETY SYSTEM

Although the FDA’s role in ensuring safe food needs to be reviewed in the context of the U.S. national food safety system, for brevity the discussion in this section is limited to information that pertains to the FDA and is needed as context for the reminder of this report. Previous reports have reviewed the food safety system in the United States (IOM/NRC, 1998; GAO, 2004a,b,c, 2008b; Becker and Porter, 2007), and the reader is referred to those reports for a more detailed description and historical context of the U.S. food safety system as a whole.

Organization

Table 2-1 lists the main federal agencies that have responsibility for food safety under at least 30 laws. Of these agencies, eight have primary responsibility for ensuring food safety: two under HHS—the FDA and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); four under USDA—the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), the Agricultural Marketing Service, the Agricultural Research Service, and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture; DHS; and EPA (GAO, 2004b,c, 2005, 2008a, 2009a).

State and local governments also have food and feed safety responsi-

TABLE 2-1 Food Safety Responsibilities by Federal Agency

|

Abbreviation |

Name |

Food Safety Responsibilities |

|

CDC |

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

Prevents disease, disability, and death caused by a wide range of infectious diseases and does the following: |

|

|

|

|

|

DHS |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security |

Leverages resources within federal, state, and local governments, coordinating the transition of multiple agencies and programs into a single, integrated agency focused on protecting the American people and their homeland. |

|

DHS/CBP |

Customs and Border Protection |

Works with federal regulatory agencies to ensure that all goods entering and exiting the United States do so according to U.S. laws and regulations. |

|

DHS/OHA |

Office of Health Affairs |

|

|

DOJ |

U.S. Department of Justice |

|

|

Abbreviation |

Name |

Food Safety Responsibilities |

|

EPA |

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

Oversees drinking water and certain aspects of foods made from plants, seafood, meat, and poultry; establishes safe drinking water standards; regulates toxic substances and wastes to prevent their entry into the environment and food chain; assists states in monitoring the quality of drinking water and finding ways to prevent contamination of drinking water; and determines the safety of new pesticides, sets tolerance levels for pesticide residues in foods, and publishes directions on the safe use of pesticides. |

|

EPA/OECA |

Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assistance |

Responsible for inspection/enforcement of pesticide regulations, including the misuse of pesticides. |

|

EPA/OPPTS |

Office of Prevention, Pesticides, and Toxic Substances |

Responsible for risk assessment of pesticide residues in food, pesticide registration. |

|

EPA/ORD |

Office of Research and Development |

Provides scientific support for pesticide-related public health issues. |

|

Abbreviation |

Name |

Food Safety Responsibilities |

|

FDA |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

Oversees all domestic and imported food sold in interstate commerce, including shell eggs, but not meat and poultry, bottled water, and wine beverages with less than 7 percent alcohol. Also enforces food safety laws governing domestic and imported food, except meat and poultry, by inspecting food production establishments and food warehouses and collecting and analyzing samples for physical, chemical, and microbial contamination; reviewing the safety of food and color additives before marketing; reviewing animal drugs for the safety of animals that receive them and humans who eat food produced from the animals; monitoring the safety of animal feed used for food-producing animals; developing model codes and ordinances, guidelines, and interpretations and working with states to implement them in regulating milk and shellfish and retail food establishments, such as restaurants and grocery stores (e.g., the model Food Code, a reference for retail outlets and nursing homes and other institutions on how to prepare food to prevent foodborne illness); establishing good food manufacturing practices and other production standards, such as plant sanitation and packaging requirements and Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) programs; working with foreign governments to ensure the safety of certain imported food products; requesting manufacturers to recall unsafe food products and monitoring those recalls; taking appropriate enforcement actions; conducting research on food safety; and educating industry and consumers on safe food-handling practices. See Table 2-2 for detail on the responsibilities of the FDA centers and offices involved in food safety. |

|

FTC/BCP |

Federal Trade Commission/Bureau of Consumer Protection |

Protects consumers against unfair, deceptive, or fraudulent practices, including advertising claims for foods, drugs, dietary supplements, and other products promising health benefits. |

|

Abbreviation |

Name |

Food Safety Responsibilities |

|

NOAA/NMFS |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/National Marine Fisheries Service (under the U.S. Department of Commerce [DoC]) |

Through its voluntary fee-for-service Seafood Inspection Program, inspects and certifies fishing vessels, seafood processing plants, and retail facilities for federal sanitation standards. Provides scientific oversight and system surveillance of the DoC inspection program and seafood HACCP training. |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

Primarily responsible for meat, poultry, and egg products; see also below. |

|

USDA/AMS |

Agricultural Marketing Service |

Provides standardization, grading, and market news services for five commodities: (1) dairy, (2) fruits and vegetables, (3) livestock and seed, (4) poultry, and (5) cotton and tobacco. Enforces such federal laws as the Perishable Agricultural Commodities Act and Country-of-Origin Labeling. AMS’s National Organic Program develops, implements, and administers national production, handling, and labeling standards for organic agricultural products. |

|

USDA/APHIS |

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service |

Responsible for monitoring/surveillance of egg products, risk assessment and data collection for pesticides, and inspections, enforcement for the pesticide record-keeping program, including border quarantine activities to detect and eliminate animal health problems and exotic organisms that might harm U.S. agriculture, many of which also pose potential food safety threats. |

|

USDA/ARS |

Agricultural Research Service |

Provides data for food products and contaminants (fruits and vegetables, dairy products, eggs/egg products, meat/poultry, seafood, grain/rice/related products, imported foods, animal drugs/feeds, and pesticide residues) to support risk assessment by the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), the Economic Research Service (ERS), the Office of Risk Assessment and Cost-Benefit Analysis (ORACBA), the FDA, and EPA; broad support of Land Grant Universities for research and education across all product areas; and education in the form of information to the National Agricultural Library (NAL) and educational workshops. |

|

Abbreviation |

Name |

Food Safety Responsibilities |

|

USDA/ERS |

Economic Research Service |

Provides risk assessment for meat and poultry and data collection to support the pesticide risk assessment process as well as technical assistance to identify education needs and to analyze the effectiveness of food safety education programs. |

|

USDA/FSIS |

Food Safety and Inspection Service |

Oversees domestic and imported meat and poultry and related products, such as meat- or poultry-containing stews, pizzas, and frozen foods, as well as processed egg products (generally liquid, frozen, and dried pasteurized egg products). Also enforces food safety laws governing domestic and imported meat and poultry products by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As of April 2010, FSIS is responsible for mandatory inspection of catfish and catfish products.a |

|

Abbreviation |

Name |

Food Safety Responsibilities |

|

USDA/GIPSA |

Grain Inspection, Packers, and Stockyards Administration |

Through its oversight activities, including monitoring programs, reviews, and investigations, fosters fair competition, provides payment protection, and guards against deceptive and fraudulent trade practices that affect the movement and price of meat animals and their products. Protects consumers and members of the livestock, meat, and poultry industries. Its Federal Grain Inspection Service facilitates the marketing of U.S. grain and related agricultural products by establishing standards for quality assessments, regulating handling practices, and managing a network of federal, state, and private laboratories that provide impartial, user fee–funded official inspection and weighing services. |

|

USDA/NAL |

National Agricultural Library/USDA/FDA Foodborne Illness Education Information Center |

Collects information on human nutrition and food to support USDA programs. These programs encompass areas as diverse as human nutritional needs, food production, safety and inspection, distribution, economics, and consumer education. Because of USDA’s responsibility for food safety and inspection, NAL comprehensively collects works addressing foodborne illness, food toxicology, and food inspection. In addition, in support of USDA’s close relationship and regulatory role with the food industry, NAL collects information on the food industry and technology, including food irradiation and biotechnology. |

|

USDA/NASS |

National Agricultural Statistics Service |

Performs data collection for risk assessment of pesticides. |

|

USDA/NIFAb |

National Institute of Food and Agriculture |

Advances knowledge for agriculture, the environment, human health and well-being, and communities by supporting research, education, and extension programs in the Land Grant University System and other partner organizations. Does not perform actual research, education, and extension but helps fund them at the state and local levels and provides program leadership in these areas. |

|

USDA/ORACBA |

Office of Risk Assessment and Cost-Benefit Analysis |

Provides technical assistance to identify education needs and to analyze the effectiveness of food safety education programs. |

|

Abbreviation |

Name |

Food Safety Responsibilities |

|

US DOT/BATF |

U.S. Department of the Treasury/Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms |

Oversees alcoholic beverages except wine containing less than 7 percent alcohol, enforces food safety laws governing the production and distribution of alcoholic beverages, and investigates cases of adulterated alcoholic products, sometimes with help from the FDA. |

|

aThe Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, 21 U.S.C. §§ 601 et seq., 2008 (also known as the 2008 Farm Bill). b The Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service became the National Institute of Food and Agriculture on October 1, 2009. SOURCE: IOM/NRC, 1998; DHS, 2004; GAO, 2005; Becker and Porter, 2007; AMS/USDA, 2009; FDA, 2009a; APHIS/USDA, 2010; FoodSafety.gov, 2010; USDA, 2010b. |

||

bilities (see also Chapter 7). Forty-four states conduct inspections of food-manufacturing firms under contract to the FDA, and all 50 states have food safety and labeling programs. Additional responsibilities of state and local governments include the following:

-

implementing food safety standards, such as Good Manufacturing Practices and Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), for fish, seafood, milk, and other foods manufactured within state borders with the assistance of the FDA and other federal agencies;

-

inspecting restaurants, grocery stores, and other retail food establishments, as well as dairy farms, milk-processing plants, grain mills, and food-manufacturing plants, within the state (the states collect and analyze many food product samples);

-

using advisory and enforcement actions to protect the health of their citizens, including placing embargoes on (i.e., stopping the sale of) unsafe food products manufactured, transported, or distributed within state borders;

-

providing safety training and education to food establishment personnel and industry as requested;

-

preparing for and participating in food recall events and foodborne outbreak investigations independently or with the FDA and other federal agencies (this may include ordering recalls of contaminated foods within state borders and taking enforcement actions against firms within state borders);

-

collecting representative samples according to established procedures and with a documented chain of custody (These samples are

-

then tested at state regulatory laboratories so they can be evaluated for compliance with food regulatory laws.);

-

receiving, evaluating, and responding to consumer complaints relating to products manufactured, purchased, or consumed in their state;

-

conducting epidemiological investigations of people who have become ill or injured (State, county, and local health officials serve the primary on-site epidemiological role in the United States and coordinate among one another and with CDC in situations of multistate outbreaks.);

-

responding to natural disasters—earthquakes, floods, hurricanes—to assess the impact on food safety and take immediate action to prevent problems in affected areas; and

-

issuing consumer health advisories or warnings through typical media and outreach channels.

The FDA’s Responsibilities for Food Safety

The FDA’s responsibilities for food safety are only part of its wide range of responsibilities. The agency has regulatory authority over more than $1 trillion in products sold annually—about 25 cents of every dollar spent by consumers (Fraser, 2009). The FDA is required to oversee the safety of all food products with the exception of meat, poultry, and some egg products. Additionally, the agency’s food safety charge includes the safety of animal feed for both pets and food-producing animals (e.g., swine, dairy cattle). In addition to food, moreover, the FDA’s jurisdiction extends to drugs, biologics, medical devices, and tobacco.2 According to the agency’s mission statement,

1) FDA is responsible for protecting public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, medical devices, our nation’s food supplies, cosmetics and products that produce radiation. 2) The FDA is also responsible for advancing the public health by helping to speed innovations that make medicine and foods more effective, safer, and more affordable; and helping the public get the accurate science-based information they need to use medicines and foods to improve their health. (FDA, 2009a)

The FDA has six program centers: (1) the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, (2) the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, (3) the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, (4) the Center for Food Safety

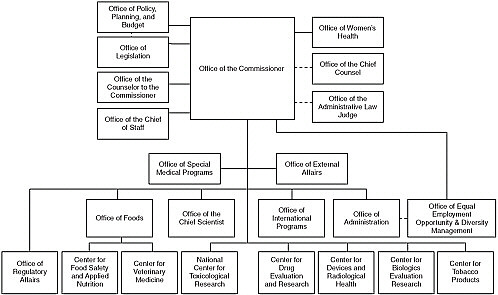

and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), (5) the Center for Tobacco Products, and (6) the Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM). The FDA also has a number of cross-cutting offices that report directly to the FDA Commissioner, including the Office of Operations, the Office of Scientific and Medical Programs, the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA), the Office of International Programs, and the Office of Planning, Policy, and Preparedness. A recent addition has been the Office of Foods, which reports directly to the Commissioner (see Figure 2-1) (FDA, 2010b).

In response to the increasing volume of imported products, including foods, the agency recently embarked on the Beyond Our Borders initiative, establishing offices in foreign countries under the Office of International Programs. As of 2009, countries with one or more U.S. offices included Belgium, China, Costa Rica, India, and Mexico. Although the long-term roles of these offices are still in the planning stages, the Beyond Our Borders initiative is designed to build or further strengthen relationships, help in learning more about the industries in these countries, facilitate and leverage inspection resources, increase interactions with foreign manufacturers, and verify that products meet U.S. standards (FDA, 2009b).

The main FDA offices with responsibility for food safety are the Office of the Commissioner, the Office of Foods, CFSAN, CVM, ORA, and the National Center for Toxicological Research (NCTR) (see Table 2-2) (FDA, 2010c).

The regulatory authority for foods is derived primarily from the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA)3 and its amendments. Recent amendments include the Infant Formula Act of 1980, the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002, and, more recently, the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (Fraser, 2009). In some fundamental respects, the law under which the FDA must ensure the safety of 80 percent of the nation’s food supply4 remains unchanged since 1938, despite the dramatic changes in food production, processing, and distribution that have taken place since (as discussed earlier in this chapter). Bills currently under consideration in Congress would give the FDA new authorities and, if enacted, would result in significant changes in the way food safety is managed.5

|

3 |

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), 21 U.S.C. §§ 301 et seq., 1938. |

|

4 |

The term “food,” as defined in the FDCA, includes “all articles used for food or drink for man or other animals,” and thus encompasses what is commonly known as animal feed. Throughout this chapter, therefore, as throughout the report generally (see Chapter 1), the word “food” includes animal feed unless otherwise noted. |

|

5 |

HR 2749, Food Safety Enhancement Act of 2009; S510 IS § 206: FDA Food Safety Modernization Act 2009. |

TABLE 2-2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Offices and Centers with Responsibility for Food Safety

|

Office |

Responsibilities |

|

Office of Foods |

|

|

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) |

Focuses on foods and applied nutrition, but also has responsibility for regulating the safety of cosmetic products. Except for food and color additives, generally it does not have premarket approval authority (in contrast with the centers that deal with drugs and devices, which generally must preapprove products before they can be put on the market). The prevailing regulatory philosophy is that the manufacturer has the primary responsibility for putting a safe product on the market. According to CFSAN’s mission statement, “CFSAN, in conjunction with the agency’s field staff is responsible for promoting and protecting the public’s health by ensuring that the nation’s food supply is safe, sanitary, wholesome, honestly labeled, and cosmetic products are safe and properly labeled.” Specific responsibilities include |

|

|

|

|

Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) |

Regulates foods used to feed animals, including pet food, as well as devices and drugs for animals, which must gain FDA premarket approval (except animal devices). According to CVM’s mission statement, “It’s a consumer-protection organization that fosters public and animal health by approving safe and effective products for animals and by enforcing other applicable provisions of the FDCA [Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act] and other authorities” (FDA, 2009c; Fraser, 2009). |

|

Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) |

With a headquarters location and field offices across the country, serves as the FDA’s broad compliance and enforcement arm. ORA has responsibility to “protect consumers and enhance public health by maximizing compliance of FDA regulated products and minimizing risk associated with those products.” In a presentation to the committee, the FDA clarified that within ORA, work to foster compliance is often done in partnership not only with the FDA centers but also with industry. During an outbreak, ORA field investigators work closely with the center that is impacted, conduct investigations, and decide on courses of action (FDA, 2009c; Fraser, 2009). |

|

National Center for Toxicological Research (NCTR) |

|

Budget, Strategic Planning, and Performance Measures

Budget

Annual funding for the FDA is provided in the Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies appropriations bill and is handled by the corresponding appropriations subcommittees in the House and Senate. The total amount the agency can spend is composed of direct appropriations (budget authority) and other funds, mainly user fees. Occasionally, funds are earmarked for various activities or offices by Congress. Implementation of the budget for food programs involves a great deal of collaboration among the centers, ORA, and leadership of the FDA food programs.

Table 2-3 shows the FDA budgets for fiscal years (FYs) 2008, 2009, and 2010 and the President’s FY 2011 budget as presented in February 2010. After many years of declining funds and personnel, resources for the agency’s food programs have recently increased from 2007 levels (note that the food programs include food safety and nutrition funding).

Appropriations for the FDA’s food safety program increased in FY 2009 by $141.5 million to a total of about $644 million, or a little less than 25 percent of the agency’s overall budget. The distribution of FY 2009 $141.5M food safety budget increase was as follows: CFSAN received $32 million, ORA $90 million, and CVM $6.4 million.

The FDA’s budget for food safety comes not only from its budget for food programs, but also from the budgets for the animal drug and feeds program and NCTR, as well as other budgets. In 2009, the FDA proposed an initiative called Protecting America’s Food Supply6 for which a budget increase of $259.3 million was requested for FY 2010, bringing the total budget for food safety to more than $1 billion (HHS, 2009). This increase was the highest among FDA programs for that year. The administration justified the budget request with reference to investments that would strengthen the safety and security of the food supply chain, including enhancements to the system needed as a result of recent food safety events, the dramatic growth in food imports, and changes in food processing and distribution practices. Among the priorities mentioned in the budget justification were the creation of a food safety system that would integrate federal and state programs, the development of preventive controls, increased frequency of domestic and foreign inspections, improved laboratory capacity and food surveillance, and enhanced information technology (IT) to support all food safety programs. The proposed 2011 budget increases the agency’s

|

6 |

See http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm152276.htm (accessed October 8, 2010). |

TABLE 2-3 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Budgets for Fiscal Years (FYs) 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011 (in millions)

|

|

FY 2008 (Enacted) |

FY 2009 (Enacted) |

FY 2010 (Appropriation) |

2011 President’s Budget |

|

Total FDA |

2,420 |

2,691 |

3,284 |

4,023 |

|

$ |

1,870 |

2,055 |

2,362 |

2,508 |

|

User fees |

549 |

636 |

922 |

1,233 |

|

FTEsa |

NA |

11,413 |

12,335 |

13,677 |

|

Total Food Programs |

577 |

644 |

784 |

1,042 |

|

Center |

NA |

210 |

237 |

337 |

|

Field |

NA |

434 |

547 |

705 |

|

User feesb |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

194 |

|

FTEs (center) |

NA |

854 |

981 |

1,186 |

|

FTEs (field) |

NA |

2,165 |

2,505 |

2,902 |

|

Total Animal Drugs and Feeds |

115 |

133 |

156 |

175 |

|

Center |

NA |

90 |

102 |

113 |

|

Field |

NA |

43 |

53 |

62 |

|

User fees |

14 |

20 |

23 |

24 |

|

FTEs (center) |

NA |

424 |

447 |

472 |

|

FTEs (field) |

NA |

238 |

278 |

319 |

|

NOTE: FTE = full-time equivalent; NA = not available. a In general, the numbers of FTEs decreased from 1992 to 2007 and increased thereafter, in parallel with increases in the FDA’s budget for food programs. (The FDA could not provide the number of food-dedicated FTEs at the Center for Veterinary Medicine because its staff is also responsible for products other than foods [e.g., approval of animal drugs]). b Current law includes user fees for animal drug approval and export color certification (certification ensures that products meet regulatory requirements for exportation). Incorporated in the FY 2011 budget for the FDA’s food programs is approximately $194 million in user fees, which has been proposed by Congress for registration of food facilities, reinspection, and food and feed export certification. SOURCES: HHS, 2008, 2009, 2010. |

||||

funding for food safety by $318 million. Major activities mentioned to justify this increase include setting standards to integrate state and federal programs and enhancing analytical tools and laboratory capacity. Increased inspection is also proposed.

Strategic Planning and Performance Measures

Strategic planning involves fundamental decisions about the nature, mission, and goals of an organization. When a strategic plan is linked to performance measures, an approach that has been adopted by the federal government, it is also a tool to enhance accountability, which is especially

important as the FDA uses public money to implement its plan. The Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 requires that all cabinet-level departments and independent agencies develop a strategic plan covering 6 years, with updates every 3 years.7 Under this act, HHS is required to have a strategic plan, but not the FDA, which is a sub-cabinet-level department within HHS; however, all the operating divisions of HHS do in fact develop such a plan. As discussed further below, the FDA last developed a strategic plan in 2007.

An additional requirement of the 1993 act is an annual performance plan and a report on how well that plan was implemented during the previous year. During the Bush Administration, the performance plan and report for HHS were integrated with the annual budget submission to Congress. This year, the integrated FY 2010 performance plan and report for HHS were provided as an appendix to the budget request to Congress in compliance with HHS performance planning and reporting requirements (HHS, 2009). The Program Assessment Rating Tool was also introduced during the Bush Administration as a governmentwide evaluation tool, with strategic planning being one of the areas assessed (OMB, 2008). Chapter 3 of this report includes a list of performance measures that have been used by the FDA and are linked to long- and short-term objectives. The President’s FY 2011 budget as presented in February 2010 introduces a significant number of new performance measures in the area of food. For example, a reduction in the number of days spent on subtyping priority pathogens in food is linked to the strategic objective of detecting safety problems earlier (HHS, 2010).

Reorganization at the FDA

CFSAN has undergone various reorganizations in an attempt to become more efficient and to adopt new ways of accomplishing its mission under new circumstances. For example, in 1992, as a result of concern expressed by FDA leadership about the ability of the agency’s food programs to address emerging food safety issues, the FDA (1) conducted a management study of CFSAN’S programs and activities, (2) reorganized CFSAN and created organizational units to respond directly to certain new food technologies, and (3) established an advisory committee on issues related to food safety. The intent was to make the center more efficient in performing its scientific and regulatory activities and to enhance its ability to meet new challenges. The reorganization was aimed at integrating policy, regulatory, and scientific specialists into offices according to their areas of expertise.

The FDA believed this new structure would increase managers’ accountability for program results and streamline approvals (Suydam, 1996; Johnson et al., 2008). This reorganization was a major change for a center that had been organized by scientific discipline (i.e., toxicology, physical sciences, and nutrition) for the previous 20 years. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO, 1992), concern arose at the time that the reorganization’s dispersion of scientists could threaten the agency’s science base and impede consistency.

Since 1992, other reorganizations have occurred at the FDA. Most notably, the agency was reorganized in 2007 in an effort to consolidate its structure, realign programs with similar or overlapping functions and operational activities, and improve communication and coordination.8 To reduce the number of management layers, most research activities were merged into two primary offices and the compliance and enforcement functions into one office. The ultimate goal was to maintain a strong and flexible food safety system as new public health challenges continued to emerge. In 2007, the Office of Food Protection was established under the commissioner’s oversight to develop an agencywide, visionary strategy for food protection and serve as a liaison to HHS on food protection issues. This office has now merged into the new Office of Foods, headed by a new deputy commissioner of foods and having responsibility and authority for all aspects of food policy under agency jurisdiction (see Box 2-1). Figure 2-1 (presented earlier) reflects these latest changes, plus the addition of the Office of Foods, in 2009 (FDA, 2009d).

Since the Obama Administration took office, the FDA has undergone further changes, which continue even as this report is being written. With a greater emphasis on food safety and public health and an increase in resources for 2010 (see above) (Hamburg and Sharfstein, 2009), the new administration is making substantive attempts to effect strategic changes, for example, through the creation of the White House Food Safety Working Group (FSWG).

RECENT ANALYSES OF FOOD SAFETY MANAGEMENT AT THE FDA9

Over the years, the U.S. government has changed its food safety management approach to meet new challenges and adapt to changes in cir-

|

8 |

Personal communication, Robert Brackett, Director and Vice President, National Center for Food Safety and Technology, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, July 14, 2009. |

|

9 |

This section does not reflect the conclusions of the committee but instead summarizes the findings of various other reviews of the U.S. food safety system focusing on the FDA. (To complement this section, Appendix B contains numerous recommendations made over the last two decades for enhancing the FDA’s management of food safety.) |

|

BOX 2-1 Responsibilities of the Office of Foods

SOURCE: FDA, 2009d. |

cumstances and expectations, scientific advances, and new evidence-based understanding of effective management practices. For example, since the mid-1990s, greater emphasis has been placed on preventive programs, such as HACCP, and on industry responsibility. In 1997, after a series of serious foodborne outbreaks, President Clinton announced a request for $43.2 million to fund a nationwide early-warning system for foodborne illness, increase seafood safety inspections, and to expand food safety research, training, and education. In addition, the Secretary of Agriculture, the Secretary of HHS, and the Administrator of the EPA were directed to identify specific steps to improve the safety of the nation’s food supply (FDA/USDA/EPA/CDC, 1997).

Several initiatives, including science-based HACCP regulatory programs for seafood (FDA/HHS, 1995), meat and poultry (FSIS, 1996), and juice (FDA/HHS, 2001), reflected an effort not only to place greater emphasis on prevention, but also to be more flexible in the governance of food safety by allowing manufacturers to identify their own preventive controls. (For a more detailed description of the progression of food safety philosophies over the years, see Chapter 1 of the IOM/NRC report Scientific Criteria to Ensure Safe Food [IOM/NRC, 2003]).

Reported Funding Discrepancies Based on Volume of Foods

According to GAO, the FDA is responsible for approximately 80 percent of the nation’s food supply, yet the federal funds the agency receives do not reflect this level of responsibility (GAO, 2004c).10 Whereas more than 75 percent of consumer expenditures on food are for FDA-regulated products, roughly 60 percent of food safety funding is allocated to USDA (GAO, 2004c). The reason for this disparity lies partly in the federal laws governing food safety, which require USDA/FSIS (the agency with responsibility for meat, poultry, and egg products) to conduct daily inspections of meat and poultry processing plants and carcass-by-carcass inspections of slaughtered animals (GAO, 2004c).

Fragmented Nature of the Food Safety System

The 30 laws that govern food safety activities were enacted over time between 1906 (the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act) and today (e.g., HR3580, the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007), and they are based on the issues that were faced in each time period—there has been no overall strategic design to the food safety system. For example,

|

10 |

In 2009, the budgets for food safety were $649 million for the FDA and $1,092 million for USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (www.fda.gov; www.usda.gov). |

the FDA was created (in its first incarnation as the Bureau of Chemistry under USDA) to prohibit adulterated and misbranded food and drugs in interstate commerce. The FDCA of 1938, which established the current FDA, was passed in response to the 1937 Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster.11

According to a recent GAO report, this situation results in “fragmentation and overlap,” as well as the lack of a strategic design to protect the public health. According to GAO, “What authorities agencies have to enforce food safety regulations, which agency has jurisdiction to regulate what food products, and how frequently they inspect food facilities is determined by the legislation that governs each agency, or by administrative agreement between the two agencies, without strategic design as to how to best protect public health” (GAO, 2004c, p. 4).

Gaps in the System

Although there is overlap in the U.S. food safety system in some areas (e.g., inspection of certain establishments), past reviews have identified some gaps that could result in threats to food safety. These gaps are most obvious in two areas—imported foods and on-farm food safety—and relate to both intentional and unintentional threats. For example, GAO has expressed concern about the food safety system because both the FDA and USDA lack statutory authority to “regulate all aspects of security at food-processing facilities” (GAO, 2004c, p. 16).

Imported Foods

As discussed earlier, a significant portion of the nation’s food supply—and more than 75 percent of its seafood—comes from abroad; however, the FDA inspects less than 2 percent of imported foods (GAO, 2004c; FDA Science Board, 2007). GAO also found that while USDA saves money and time by mandating U.S.-equivalent food safety standards for countries supplying imports, the ability of the FDA to do the same needs strengthening (GAO, 2004c). The Interagency Working Group on Import Safety’s 2007 Action Plan for Import Safety requests additional, expanded, or strengthened authorities for the FDA to require preventive controls for certain foods, measures to prevent the intentional contamination of foods, and certification or other assurance that a product under its jurisdiction complies with agency requirements (Interagency Working Group on Import Safety, 2007). The report specifically cites the FDA as the lead for its recommendations or requests for new authorities more frequently—28 times—than is the case

|

11 |

See http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/ProductRegulation/SulfanilamideDisaster/default.htm (accessed October 8, 2010). |

for any other agency (Interagency Working Group on Import Safety, 2007). A 2009 GAO report recognizes that some steps have been taken to ensure the safety of imported foods but also highlights gaps in enforcement and collaboration among U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the FDA, and FSIS (GAO, 2009b). Appendix E contains a detailed discussion of the FDA’s imported food program.

On-Farm Food Safety Policies

On-farm regulation has received increased attention recently as a result of outbreaks involving pathogen-contaminated fresh produce. The FDA relies almost completely on voluntary guidance documents and initiatives (for example, the Produce Safety Initiative) for on-farm regulation (Becker, 2009). Occasionally it will inspect farms, but almost exclusively during periods of crisis (FDA Science Board, 2007). Although the FDA had requested authority to regulate shell eggs, such measures were postponed because of industry concerns (Becker, 2009); the Egg Safety Rule, which regulates the production of shell eggs on the farm, was published only recently (FDA/HHS, 2009). A further barrier to the FDA’s on-farm efforts lies in the FDCA, in which farms are specifically exempted from requirements for record keeping (Consumers Union, 2008) and registration. Both exemptions hinder traceability, and ending these exemptions is a recurrent recommendation of GAO and other groups to help protect the public health (DeWaal, 2003; Consumers Union, 2008).

Lack of Mandatory Recall Authority

Also lacking is authority for the FDA to order mandatory food recalls—aside from infant formulas (USDA also lacks this authority [Brougher and Becker, 2008; GAO, 2008b]). The need for this authority is controversial because some argue that in the majority of cases, food companies voluntarily recall products suspected of being contaminated (Degnan, 2006), and that the FDA already has legal authority to seize adulterated and misbranded products and to administratively detain articles of food for which it “has credible evidence or information indicating that such article presents a threat of serious adverse health consequences or death.”12 In addition, the FDA routinely uses the embargo authority of the states to remove and hold products off market until federal seizure actions can be implemented. In support of mandatory authority, however, others observe that detention procedures must be carried out through the courts and therefore are not expeditious; meanwhile, the food supply and public health are endangered

(GAO, 2004b, 2008b). Moreover, when manufacturers or producers issue a recall, neither the FDA nor USDA has mechanisms for tracking the recall’s effectiveness or accounting for the recalled products. Nor does either agency mandate timelines for recalls (GAO, 2004b). A 2004 GAO report found that, in some cases, the time it took for the agency to verify a recall was longer than the shelf life of the recalled products (GAO, 2004b). Accordingly, both consumer groups and GAO have recommended that the FDA and USDA be given mandatory recall authority (GAO, 2004b, 2008b; Consumers Union, 2008), and in the FDA’s Food Protection Plan (FPP), the agency itself requests this authority (FDA, 2007; GAO, 2008b).

The FDA’s Use of Resources

Groups such as the Alliance for a Stronger FDA,13 Consumers Union, and the IOM have for years called for increased funding for the FDA (IOM/NRC, 1998; Consumers Union, 2008). Yet while the FDA’s funding and staffing levels have not kept pace with its increased workload, the agency has opportunities to improve the management of its resources (GAO, 2008a). For example, GAO has identified some overlap in the activities of USDA and the FDA, including inspection and enforcement, training, research, and rulemaking. By simply enforcing interagency agreements, the FDA could “leverage inspection resources and possibly avoid duplication of effort” (GAO, 2005, p. 33). The same report suggests that the FDA and USDA consider a joint inspection training program. These examples illustrate the potential for savings and better use of limited resources (GAO, 2005, 2008a).

Inspection

In 2004 and 2005, GAO identified the three main deficiencies in the FDA’s inspection program as (1) duplication of effort, (2) insufficient inspection, and (3) a poor basis for determining which facilities to inspect (GAO, 2004c, 2005). According to GAO, in 2003 USDA and FDA inspection and enforcement activities included overlapping inspections of 1,451 domestic food-processing facilities that produce multi-ingredient foods. This overlap occurs because of the differences in the statutory responsibilities of the two agencies.

Insufficient inspection takes many forms. Facilities can go as long as 10 years without an inspection, and the rate of inspection has declined by 78 percent in the past 35 years (FDA Science Board, 2007). GAO reported in 2004 that the FDA had roughly 1,900 full-time equivalents (FTEs) who

|

13 |

See http://www.strengthenfda.org/members.htm (accessed October 8, 2010). |

inspected an estimated 57,000 facilities. In comparison, USDA had 9,170 inspectors for “daily oversight of approximately 6,464 meat, poultry, and egg product plants” (GAO, 2004c, p. 10). Further, these 1,900 FTEs were also responsible for inspecting other FDA-regulated products. In fact, the FDA was unable to tell the committee specifically how many FTEs were dedicated to food inspections (Givens, 2009). Without a sufficient number of inspectors and inspections, the agency cannot ensure the safety of the food supply (FDA Science Board, 2007). To illustrate the problem, the Peanut Corporation of America facility, at the root of a 2009 salmonella outbreak that sickened 700 people and contributed to 9 deaths, had last been inspected by the FDA in 2001, 8 years before the outbreak. Intermittent inspections had been conducted by the state of Georgia, but significant problems had not been detected, leading the recently appointed Advisor to the FDA Commissioner on Food to say during the outbreak that it was an example of “a basic breakdown” and to call for the agency to raise its standards (Schmidt, 2009).

Prior reports have expressed concern about insufficient inspection with respect to certain kinds of commodities—fresh produce and imported products—and certain kinds of facilities, such as farms (see On-Farm Food Safety Policies). When the FDA conducts fresh produce inspections—which declined in number to just 478 in FY 2007—it tests primarily for pesticide rather than microbial contamination (GAO, 2008c).

The 1998 IOM/NRC report Ensuring Safe Food notes that, although there is a computer system to track FDA- and USDA-regulated imported products and their inspection, “there is no way to determine whether the agencies are focusing their attention on the most important health risks” (IOM/NRC, 1998, p. 89). The FDA lacks control over detained imported shipments and does not punish those who violate the rules. Seafood is inspected minimally, although, as noted earlier, 75 percent of seafood consumed in the United States is imported, and shellfish alone is reported to have caused 21 percent of all foodborne illness from 1978 to 1992 (IOM/NRC, 1998; GAO, 2004c). This situation reflects an inherent flaw in FDA inspections: they are not risk-based in frequency or in facilities targeted (GAO, 2004c). Federal regulation, not risk, determines which facilities are inspected by which agency. For example, according to GAO, the frequency of inspection of a facility that produces ham and cheese sandwiches depends on the percentage of meat used rather than on risk (GAO, 2004c). The law, in this case, inhibits science-based decisions in food safety programs (IOM/NRC, 1998).

Research

Without an adequate research program, there is insufficient information with which to make science-based decisions (IOM/NRC, 1998). Indeed, a thorough scientific understanding of threats to the food supply would likely be more cost-effective for the FDA in the long term than simply adding more inspectors.

In 2007, the FDA Science Board completed a general review of the agency’s research programs. The review concluded that these programs were in urgent need of enhancement. The Science Board’s report stated that basic research programs and risk assessments would determine pressing risks to the food supply so that the agency’s limited funds could be used for targeted research to address those risks (FDA Science Board, 2007). The agency maintains several research centers at academic institutions, but these, too, are poorly funded. When the Science Board examined CFSAN’s critical research priorities, such as detection of foodborne viruses, many were found to be on target, but the agency does not always maintain staff with scientific expertise in those areas. It was suggested that some of these priorities could be shared with USDA (FDA Science Board, 2007). The FDA also lacks plans for critical research in other areas, such as produce safety (GAO, 2008c).

In 2007, a new center was formed to conduct research and serve as a source of scientific information to enhance food safety and defense. The Western Institute for Food Safety and Security is a program at the University of California, Davis, partnering with the California Department of Food and Agriculture, the California Department of Public Health, the FDA, and USDA. See Chapter 6 for further discussion of the FDA’s research centers and their funding.

With limited funds and inadequate staff, the FDA relies on USDA to meet some of its research needs (FDA Science Board, 2007). Much of the data the FDA needs is expensive to acquire, however, and other agencies are not willing to make the investment (FDA Science Board, 2007). Data the FDA itself collects are not available to every researcher within the agency, and data obtained by other agencies often are not made available to the FDA (FDA Science Board, 2007; GAO, 2009a).

A review of CFSAN and CVM research programs was recently initiated by subcommittees of the FDA Science Board. As of this writing, only the CVM review had been completed. The report from that review highlights that since the 2007 review (FDA Science Board, 2009), CVM has made much progress in the research function, but the report also points to areas of weakness, such as regulatory science and the external consultative process for research planning.

Information Technology Infrastructure

Related to the above problems is the lack of an adequate IT infrastructure both within the FDA and between the FDA and related agencies responsible for food safety (see Chapter 5) (FDA Science Board, 2007). Although the FDA has made progress in addressing this deficiency by hiring new staff, forming internal IT governance boards, developing strong partnerships with other agencies, and updating management systems, in 2007 the Science Board found that the FDA’s IT infrastructure could not support the agency’s public health mission (FDA Science Board, 2007). Specific problems mentioned include (1) the quality of data, which are not standardized; (2) the integration of IT systems within centers; (3) inconsistent data collection across different centers and even within discrete agency program areas (GAO, 2009a); (4) antiquated hardware lacking security measures (FDA Science Board, 2007; GAO, 2009a); and (5) delays in sharing data (FDA Science Board, 2007). A 2008 report describing the FDA’s plan to revitalize ORA proposes ways to deal with many of these IT issues. GAO supports such efforts but concludes that without initiating a strategic plan as is required by federal law, the agency may not be effective in carrying them out (Glavin, 2008; GAO, 2009a).

An example of how IT problems contribute to inefficiency is the significant duplication of effort among the agencies responsible for ensuring safe food discussed above. GAO has found that one reason this duplication occurs is that the agencies “do not have adequate mechanisms to track interagency food safety agreements” (GAO, 2005). An IT system should facilitate the FDA’s public health mission by allowing data flow and being responsive to scientific innovation, but the agency’s system does not meet these requirements (GAO, 2009a).

Lack of a Research and IT Strategic Plan

One key problem at the FDA has been the lack of an overarching strategic plan for research addressing the agency’s food safety mission. Development of a new strategic plan is said to be under way (Musser, 2009). The FDA’s efforts to enhance and modernize its programs are uncoordinated and inefficient and may lead to little or ineffectual improvement (GAO, 2009a). Without a clearly delineated mission statement, goals, and performance metrics, the agency cannot align itself with a direction, measure how well it fulfills its responsibilities, or determine the effectiveness of its programs (FDA Science Board, 2007; GAO, 2009a). The FDA needs to define its mission to meet its regulatory obligations and build its research, inspection, IT, and other programs to fulfill that mission. The Science Board report acknowledges both the lack of resources available to the FDA and the current initiatives to improve its programs, but it finds that without

clear goals, the agency cannot know, for example, what expertise is needed as it recruits new staff, what laboratory capabilities are needed, or how to organize data in an efficient and productive way (FDA Science Board, 2007).

LOOKING FORWARD

The nation is undergoing many changes related not only to technology advances, but also to changes in the way business is conducted and the way its citizens interact with the rest of the world. Although ensuring food safety is the responsibility of everyone, the public will continue to view regulatory agencies as the ultimate repository of salient scientific knowledge, reliable advisors, and overseers of food safety activities in the private sector. The flaws in the existing food safety system have been well investigated, and recent changes in the approach to food safety offer cause for hope that the nation is ready to take the steps necessary to create an efficient and effective food safety system. The first signs of progress at the FDA were seen in the development and early stages of implementation of the FPP, a document that outlines basic principles of prevention, intervention, and response for food safety and defense of domestic and imported products (FDA, 2007). However, a 2008 GAO report states that, while the FPP proposes some positive first steps to enhance oversight of food safety, the plan lacks specific information about strategies and resources needed for its implementation (GAO, 2008b).

With a new FDA commissioner in place and the creation of the White House FSWG and the Office of Foods, many further positive changes are anticipated, and some of them are already well under way. In the following chapters, the committee encourages the FDA to continue with its recent initiatives and plans and to delineate a course of action that will enable it to become more efficient at carrying out its food safety responsibilities.

REFERENCES

Abbot, J. M., C. Byrd-Bredbenner, D. Schaffner, C. M. Bruhn, and L. Blalock. 2009. Comparison of food safety cognitions and self-reported food-handling behaviors with observed food safety behaviors of young adults. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 63:572–579

AMS/USDA (Agricultural Marketing Service/U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2009. About AMS. http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/ams.fetchTemplateData.do?template=TemplateD&navID=AboutAMS&topNav=AboutAMS&page=AboutAMS&acct=AMSPW (accessed May 13, 2010).

Anderson, J. B., T. A. Shuster, K. E. Hansen, A. S. Levy, and A. Volk. 2004. A camera’s view of consumer food-handling behaviors. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 104(2):186–191.

APHIS/USDA (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service/U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2010. Animal Product Manual (Second Edition). Washington, DC: APHIS/USDA. http://www.aphis.usda.gov/import_export/plants/manuals/ports/downloads/apm.pdf (accessed March 30, 2010).

Becker, G. S. 2009. Food Safety on the Farm: Federal Programs and Selected Proposals. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Becker, G. S., and D. V. Porter. 2007. The Federal Food Safety System: A Primer. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Boisen, C. S. 2007. Title III of the Bioterrorism Act: Sacrificing U.S. trade relations in the name of food security. American University Law Review 56(3):667–718.

Brougher, C., and G. S. Becker. 2008. CRS Report for Congress: The USDA’s Authority to Recall Meat and Poultry Products. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Carnevale, C. 2009. FDA and Import Food Safety: A Briefing Paper. Paper presented at Institute of Medicine/National Research Council Committee on Review of the FDA’s Role in Ensuring Safe Food Meeting, Washington, DC, October 15, 2009.

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2009. Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of infection with pathogens commonly transmitted through food—10 states, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 58(13):333–337.

CDC. 2010. Preliminary FoodNet Data on the incidence of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food—10 states, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 59(14):418–422.

Consumers Union. 2008. Increased Inspections Needed for Produce, Processing Plants to Protect Consumers from Unsafe Food. http://www.consumersunion.org/pub/core_food_safety/005732.html (accessed January 28, 2010).

Degnan, F. H. 2006. FDA’s Creative Application of the Law: Not Merely a Collection of Words (Second Edition). Washington, DC: Food and Drug Law Institute.

DeWaal, C. S. 2003. Safe food from a consumer perspective. Food Control 14(2):75–79.

DeWaal, C. S. 2009. Zero Tolerance: Pros and Cons. Paper Presented at the International Association for Food Protection 96th Annual Meeting, Grapevine, TX, July 15, 2009.

DeWaal, C. S., and D. Plunkett. 2007. Building a Modern Food Safety System: For FDA Regulated Foods, CSPI White Paper. Washington, DC: Center for Science in the Public Interest.

DHS (U.S. Department of Homeland Security). 2004. Fact Sheet: Strengthening the Security of Our Nation’s Food Supply. http://www.dhs.gov/xnews/releases/press_release_0453.shtm (accessed March 25, 2010).

ERS (Economic Research Service). 2010. Food CPI and Expenditures. http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/CPIFoodAndExpenditures/ (accessed January 28, 2010.