1

Introduction

The public will support science only if it can trust the scientists and institutions that conduct research.

The achievements of science in formulating a systematic knowledge of the physical, biological, and social world have been breathtaking. Study of both the very large and the very small has revealed that the universe began with an initial singularity and has deepened our knowledge of its expansion over more than 13 billion years. Research into the fundamental building blocks that make up living things has unlocked mysteries of heredity, biochemical bases of diseases, and pathways to improved medicines and better health. Examination of brain function is providing new insights into learning, emotion, and mental disorders. Studies of human communities have contributed knowledge of psychological, social, and political behaviors to inform a continued expansion of human well-being consistent with environmental sustainability.

This astonishing growth in human knowledge has been accompanied by a dramatic explosion of technologies designed to meet human needs and enhance human well-being. New drugs and devices, including imaging devices based on research into the properties of materials, have contributed to the extension and improvement of human life. The development of digital technologies has not only expanded human capabilities but has created entirely new ways of communicating, sensing, analyzing, learning, and doing research. Advances in agriculture, transportation, and food science have increased human capacities to feed a growing world population. Often drawing inspiration from scientific research and sometimes enabling that research, technological and other forms of innovation have become a mainstay of modern economies.

A major contributor to the remarkable progress of science and technology has been the ability of the research enterprise to continuously build upon a foundation of knowledge created by previous researchers. The stability of this founda-

tion has resulted from the adherence of researchers to good research practices and from their openness in communicating research procedures and results. By communicating the assumptions made and methods used in conducting experiments, researchers allow others to replicate, extend, and, where necessary, correct their work. When undertaken with fidelity, science becomes a cumulative exercise that produces a growing body of reliable knowledge.

Science progresses through both success and failure. Modest gains are not just incremental but are interspersed in unpredictable ways with huge breakthroughs followed by periods of consolidation. Research frequently returns negative results, and such failures are necessary to push the boundaries of knowledge forward. Even when researchers are careful and scrupulous, results will be reported that later turn out to be the result of incomplete understanding, honest errors in performing experiments and interpreting data, or limitations in the capabilities of research instrumentation available at a particular time. Adherence to good practices and values such as openness and transparency minimizes missteps and increases the likelihood of efficient progress toward new, reliable knowledge: it enables good science.

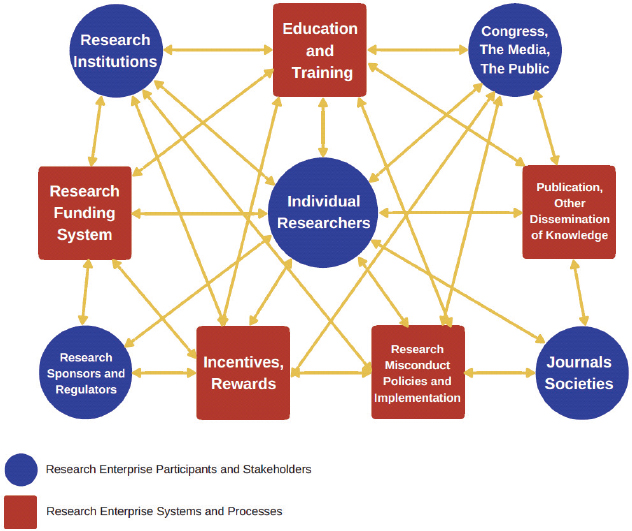

The research enterprise is a system of individuals, organizations, and relationships that requires its constituents to fulfill their responsibilities in order to be effective. In contrast to simple systems, which are stable and whose components interact through well-understood cause-and-effect relationships, the research enterprise is more akin to a complex adaptive system characterized by dynamism and self-organization. Such systems “can be highly organized without any conscious leadership, direction, or management” and exist “within other interdependent systems” (McKenzie, 2014). The components of complex adaptive systems change as they interact with each other. Cause-and-effect relationships within the system are influenced by feedback effects, and “changes in one part of the system can cause changes in other parts of the system, often in nonlinear and unpredictable ways” (McKenzie, 2014).

Figure 1-1 illustrates the research enterprise as a complex adaptive system. The figure, which is meant to be stylized and heuristic rather than purely and exhaustively descriptive, distinguishes two conceptually distinct “components” of the system: participants and stakeholders, and systems and processes. These components interact with one another and across the two types in ways that may be bidirectional, implying the existence of nonlinearity, feedback loops, and complex causality. As discussed in other parts of this report, some components of the research enterprise operate at a local level (research institutions) or a national level (research funding systems, to a large extent). Other components, such as publication and the dissemination of knowledge, operate largely at a global level.

Some researchers deviate from the norms and practices that they are expected to fulfill. The reasons can be complex, including intentional or negligent actions resulting from carelessness or other individual shortcomings coupled with environmental pressures and institutional practices. Deviations from good science

can cause great damage to the research enterprise—both in the practice of science and in how that science is perceived in the broader society. Organizations such as research institutions, research sponsors, and journals may also engage in detrimental research practices. Even fields and disciplines may fail to define and uphold necessary standards in areas such as data sharing, in effect tolerating detrimental research practices.

Making matters more complex, in recent years the research enterprise has been changing in ways that can make both the identification and the application of best practices more difficult than in the past. For example, ensuring research integrity may require encouraging and rewarding behaviors that have not been valued in the past, such as publication of negative results.

A central goal of this report is to identify best practices in research and to recommend practical options for discouraging and addressing research misconduct and detrimental research practices. The sustainability of the scientific enterprise, both as a body of practice and as a legitimate, authoritative contributor to societal ends, depends in no small part on putting best practices to work across the entire system.

THE 1992 RESPONSIBLE SCIENCE REPORT

In 1989, the Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy of the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine formed a 22-member panel to conduct a major study of issues related to scientific responsibility and the conduct of research. The goals of the panel were to review factors affecting the integrity of science and the research process, to recommend steps for reinforcing responsible research practices, to review institutional mechanisms for addressing allegations of misconduct in science, and to consider the advantages and disadvantages of formal guidelines and enhanced educational efforts for the conduct of research.

In 1992, the panel released its report Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process (NAS-NAE-IOM, 1992). The panel defined the term “integrity of the research process” as “the adherence by scientists and their institutions to honest and verifiable methods in proposing, performing, evaluating, and reporting research activities.” The panel also developed a framework that distinguishes three categories of behaviors that can compromise the integrity of research. Misconduct in science was defined as “fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reporting research.” Questionable research practices were defined as “actions that violate traditional values of the research enterprise and that may be detrimental to the research process.” Other misconduct was defined as “forms of unacceptable behavior that are clearly not unique to the conduct of science, although they may occur in the laboratory or research environment.”

WHY REVISIT THESE ISSUES?

The 1992 Responsible Science report provided a valuable service in describing and analyzing a very complicated set of issues, and it has served as a crucial basis for thinking about research integrity for more than two decades. However, as experience has accumulated with various forms of research misconduct, detrimental research practices, and other forms of misconduct, as subsequent empirical research has revealed more about the nature of scientific misconduct, and because technological and social changes have altered the environment in which research is conducted, it is clear that the framework established more than two decades ago needs to be updated. In order to develop more robust approaches to ensuring research integrity in the current research environment, it is necessary to revisit some of the issues addressed in Responsible Science.

A recent case illustrates some of the questions and issues that should be rethought. On August 5, 2014, stem cell biologist Yoshiki Sasai of Japan’s RIKEN (a large research institution) was found dead in an apparent suicide. Sasai had been the supervisor of Haruko Obokata, another RIKEN researcher, and one of Obokata’s coauthors on two papers published in the journal Nature purporting to have discovered an easy way to transform ordinary cells into pluripotent stem

cells, which would give a significant boost to a variety of therapies that utilize stem cells (Obokata et al., 2014a,b). Earlier versions of the work had been rejected by Nature and several other journals before being published in early 2014 (Vogel and Normile, 2014). Questions about the work arose almost immediately, as many researchers around the world set out to replicate and extend the remarkable results and failed. RIKEN promptly conducted an investigation, concluding that Obokata had fabricated and falsified data (Ishii et al., 2014) (Appendix D provides a full case description).

This case shares many elements with several other high-profile misconduct cases that have emerged in recent years, including (1) a striking, counterintuitive result trumpeted in a prestigious journal; (2) the apparent failure of supervisors at the lab and institutional levels as well as other coauthors to check or question data that turned out to be fairly obviously fabricated or falsified; (3) international coauthorship that illustrates the global nature of challenges to integrity; and (4) a publication whose results are immediately cast into doubt by the relevant research community, perhaps because the publication is in a high-profile field where efforts to replicate and extend the work would be expected to commence soon after publication. Given that cases with similar elements appear fairly regularly, it is fair to ask several questions: Could better research practices at the lab or institutional levels, at journals, and at the field or disciplinary level prevent a significant fraction of these cases? If so, can better practices be developed and implemented so that the behavior of researchers actually changes?

The need for rethinking and reconsideration of approaches to understanding, preventing, and addressing research misconduct and detrimental research practices is reinforced by a narrative that has emerged in the scientific and general media over the past several years: that the research enterprise itself is somehow broken or seriously off track (Fang et al., 2012; Economist, 2013; Alberts et al., 2014). Some of the phenomena that have driven this narrative, in addition to the regular appearance of highly visible research misconduct cases, include growing evidence that half or more of the published results in some fields are not reproducible, the remarkable growth in the number of retractions of journal articles, and the appearance of new forms of detrimental research practices such as journals that charge authors to publish but appear to do no quality control. According to the Economist, “Fraud is very likely second to incompetence in generating erroneous results, though it is hard to tell for certain” (Economist, 2013).

The trends and phenomena listed above are discussed in detail in the report, along with possible new approaches. For the purpose of this introduction, it is important to note that the report does not conclude that science itself is broken. Rather, the research enterprise faces serious challenges in dealing with research misconduct and detrimental research practices in the current environment. For example, detrimental research practices are more widespread and may ultimately be more damaging to research than research misconduct is. In order to meet these challenges and secure the future, the research enterprise needs to make deliberate

efforts to strengthen the self-correcting mechanisms that are already an implicit part of science.

The report also concludes that, while the core values of research do not and should not change, there is a need to restate and reconfirm these values for the 21st century. Research is based on a set of enduring principles that have proven to be successful in generating empirically based knowledge of the natural world. It also takes place using particular practices, techniques, and methods that vary from one research field to another, across research groups, and over time. The ways in which science is carried out and communicated have evolved dramatically over the past two decades. The research enterprise in the United States and around the world has undergone tremendous change over this time, and these changes can have implications for how the enterprise fosters integrity. Research takes place within particular contexts that can have a powerful influence on the productivity and applicability of research both within science and in the broader society. These methods and contexts have been changing rapidly over the past two decades; this also has created new challenges to upholding research integrity.

A CHANGING ENVIRONMENT

Responsible Science contains a chapter entitled “Contemporary Research Environment” that laid out the changes in science from the post–World War II period to the early 1990s. It noted that in the 1960s a typical laboratory research group might have consisted of less than a half-dozen members, while in the 1990s larger and more diverse groups were becoming more common. It cited “the increasing complexity of contemporary research problems and instrumentation, the increasing costs of scientific research, changes in the rationale for supporting and monitoring government-funded research, and increased regulation of federal research.” As the number of government regulations and guidelines had increased, the report observed, universities had expanded administrative and oversight functions, which had the potential to create or exacerbate tensions between administrators and faculties. Also, the growing interest of private industry in research results was leading to more cooperative programs between universities and industry, encouraged by federal and state programs designed to foster such cooperation.

All of these trends have intensified since the early 1990s. Today, the research system is even larger, more complex, and more integrated into other societal sectors. In the United States, the number of science, engineering, and health doctorate holders employed in academia rose nearly 30 percent, from 211,000 in 1991 to almost 309,000 in 2013 (NSB, 2016). The number of PhDs awarded in science and engineering rose 95 percent, from approximately 19,000 in 1988 to almost 37,000 in 2013, with an increasing percentage of these doctorate recipients going to work outside academia (NSB, 2016). The number of science and engineering articles worldwide grew more than 350 percent, from approximately 485,000 in

1989 to approximately 2,200,000 in 2013, with especially rapid growth outside the United States (NSB, 2016). Government regulation of research has continued to grow, to the point where its “ever-growing requirements are diminishing the effectiveness of the nation’s research investment” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016).

Even as expansion and diversification have continued, new developments have reshaped the research enterprise since the early 1990s. These include:

Collaboration. The increasing prevalence of multi-investigator, interdisciplinary research has led to the creation of research teams where sometimes no one member can understand the details of all of the science encompassed by the research. In such circumstances, collaborative research must include structures that coordinate and verify the integrity of separate contributions to the overall research effort. These efforts are further complicated by the fact that collaborations often operate across institutional and national boundaries (see below).

Globalization. While research has always been international in many important respects, the scale and scope of research practice are globalizing to an unprecedented extent. This is seen in the spread of capabilities around the world (particularly in large emerging economies such as China, India, South Korea, and Brazil), the growth of large- and small-scale collaborations across borders, and continued internationalization of the U.S. research workforce (described in more detail in Chapter 3). Differences in culture, language, and training can lead to lack of understanding and clarity about values, roles, and responsibilities and could contribute to research environments where it is more difficult to prevent, uncover, or respond to lapses in integrity.

Funding and Organization. The funding and organization of research in the United States and the institutions that perform and communicate it have undergone some changes. For example, the share of U.S. research and development funded by industry has grown somewhat (from 58 percent in 1992 to 65 percent in 2013) while the share funded by government has shrunk (from 36 percent in 1992 to 27 percent in 2013) (NSB, 2016). However, looking only at basic and applied research and leaving development aside, the federal share of funding has held steady at about 45–46 percent while the industry share has declined from 44 percent to 36 percent. The commercialization of university research has increased over the years, as measured by patenting, licensing, and the launch of start-up companies based on university technology (AUTM, 2014).

Some of the key institutions for performing and communicating research, including research universities and scholarly journals, are experiencing significant stresses. The organizational model for academic research is shifting, with the results perhaps most visible in biomedicine: larger research groups, lower success rates on grants, a growing population of graduate students and postdoctoral fellows who are less likely to attain tenure-track or other independent research positions than previous generations, and the greater reliance of researcher sala-

ries on federal support that has sometimes moved in unpredictable ways. U.S. research universities and higher education institutions more broadly face a range of long-term pressures apart from shifts in research funding, including pressures on general funding from states (for public universities), tuition growth that has outpaced increases in the overall cost of living, demographic shifts, and disruptions caused by the advent of new technologies (NRC, 2012a).

Competitive Pressure. Increasing pressure on both junior and senior researchers to publish in prominent journals has created a bias to produce the kinds of novel, newsworthy, and paradigm-shifting results favored by these journals. Similarly, the difficulty in securing government grants and contracts along with explicit federal requirements to do so have increased the pressure on researchers to emphasize the significance and relevance of proposed research. The importance of publications in establishing the reputation of researchers and as the basis for hiring and promotion decisions has increased the potential for disputes over authorship and distorts the publication process—for example, by heightening the temptation to publish multiple papers on just one experiment or dataset.

Policy and Societal Relevance. The relationship between the research enterprise and the larger society, including policy makers and the public, has become deeper and more complex. Research is implicated in more policy areas with higher stakes, so as science is called upon to inform decision making there is more risk of research being invoked in controversies, misrepresented, or shaped to advance a desired political outcome, contributing to poor decision making and loss of public trust.

Technological Changes. Research in most fields has been transformed by the advance of technology, particularly the emergence of approaches to research across many fields that take advantage of the ability to collect and analyze large amounts of digital data and the infusion of information technologies into communications. As will be explored further in the report, technological advances have enabled new ways for researchers to err—both intentionally and unintentionally—as well as offering new tools to detect mistakes and misbehavior.

Scholarly Communications. New forms of scientific publication pose challenges to traditional peer review systems.1 Examples include non-peer-reviewed web publications that are widely available, “publication” on personal web pages, and rapid publication with continuously updated reviews. The emergence of research based on computer analyses of massive datasets raises questions about access to both the data and the computer code used to analyze the data and about the allocation of credit to those who collect, curate, and disseminate data and to those who create software and programs that perform scientific analysis on the datasets. Computational science also raises questions regarding appropriate stewardship and persistence of datasets and code.

___________________

1 This report generally uses the term peer review to refer to systems that bring expert perspectives to bear on the evaluation of articles submitted for publication and the evaluation of grant proposals. Alternative terms include merit review and expert review.

Visibility of Research Misconduct and Detrimental Research Practices. Research misconduct is reported on in the science media and in some cases the general media, with a steady stream of cases from around the world. Retractions and other indicators related to research misconduct and detrimental research practices are on the rise, and there are new mechanisms for communicating cases and trends. Policy reports on research integrity are emerging from a variety of international groups and individual countries and from the large international community of scholars, educators, and other practitioners concerned with these issues. This is reflected in phenomena such as the world conferences on research integrity and the launch of the Association of Research Integrity Officers. More detailed discussion about these trends appears elsewhere in the report. The overall result is that research misconduct and detrimental research practices are becoming more visible and attracting more attention.

Evolution of Policies. The U.S. policy framework related to research misconduct has evolved over the past two decades. Changes such as the 2000 unified federal definition and new or revised education mandates have emerged within a framework where primary responsibility for investigating and taking corrective actions in response to misconduct and other undesirable behavior lies with institutions, overseen by funding agencies. There has also been growing focus on research integrity issues around the world, with a number of individual countries adopting or changing policies, as well as reports by international bodies such as the InterAcademy Partnership (IAC-IAP, 2012; IAP, 2016). In light of other changes in the research environment, it is worth examining the current policy framework and related administrative procedures to see how they are working and whether they are adapted to research as it is performed today and as it will likely evolve in coming decades.

Improved Understanding of Research Misconduct and Detrimental Research Practices. A significant change since the publication of Responsible Science is the accumulation of knowledge through the passage of time. More cases of research misconduct, the development of empirical research on research misconduct and detrimental research practices, and better understanding of human cognition and decision making have all contributed to this knowledge. More is known about the incidence of major and “minor” departures from research norms, and about the factors that can influence behavior inside organizations. Examining the systems within which research takes place and considering how these can be designed and managed in ways that buttress and reinforce the integrity of research provides better understanding of the emerging threats to research integrity and can lead to policies and interventions that address these threats.

Adding a focus on how research environments and systemic conditions influence individual choices does not lessen the personal responsibility of researchers for their actions. Nor does it lessen the importance of educating students and working professionals about their roles in upholding the integrity of the community of scholars. Each individual retains deeply personal obligations and duties

to aspire to the highest levels of rigor in his or her work, including understanding about cognitive biases and errors to which decision-making processes are prone in order to build in safeguards and precautions against natural influences in favor of existing ideas, personal biases, the interests of funders, and the reward systems that surround the pursuit of science.

STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT

This report is divided into three parts. The first part focuses on integrity in research, including this introduction, the underlying values and norms of research, and shifts in the research system and how they affect integrity. The second part covers research misconduct and detrimental research practices, including definitions, a historical overview of how these issues have been handled by the research enterprise, incidence and consequences, understanding why researchers commit these transgressions, and how they are addressed by various stakeholders. The third part considers how the research enterprise can better foster integrity in research, including education and training, defining best practices and encouraging their adoption, and the report’s findings and recommendations.

See Box 1-1 for the committee’s task statement. The first two task elements are largely addressed in Chapter 3, with some material addressing these elements in Chapters 5, 6, and 7.2 The third task element is largely addressed in Chapters 7, 8, 9, and 10. The fourth task element is largely addressed in Chapters 4, 7, 8, and 9. The fifth task element is largely addressed in Chapters 4 and 7. The sixth task element is largely addressed in Chapters 7, 8, and 9. All of the task elements are addressed to some extent in Chapter 11. Box 1-2 contains further information about terminology used in the study.

___________________

2 Although this report contains some discussion of federal regulations covering the treatment of human research subjects and how this regulatory framework interacts with implementation of the federal government’s research misconduct policy, the committee considered institutional review boards and other elements of human subjects protections to be outside the appropriate scope of its findings and recommendations. The federal government was in the process of developing changes to the regulatory framework designed to protect human subjects—the Common Rule—during the course of this study. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine were undertaking a comprehensive study of government research regulations at the same time that this study was in process (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016).