2

Solid Organ Transplantation in the United States and the Experiences of Organ Recipients and Their Caregivers

Solid organ transplantation is a lifesaving procedure for many patients with end-stage organ failure. While the cutting-edge research, best practices, and evidence-based treatments can contribute a large amount of knowledge to the field, many workshop speakers reminded the audience that patients are at the center of the discourse about posttransplantation recovery and functioning. This chapter summarizes presentations and discussions from the first and third workshop sessions. Speakers in the first session provided an overview of the U.S. transplantation system, including how organs are donated and allocated, the availability of organs, outcome data, and disparities in the recovery and survival rates. Patients, a caregiver, and a social worker in the third session conveyed what it is like to live with an organ transplant.

OVERVIEW OF THE SOLID ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION SYSTEM

Opening the first session, David Mulligan, president of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), began by discussing how solid organ diseases, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) or cardiomyopathy, which can result in the need for a transplant, are more common than most people think and that demand far exceeds supply. Mulligan introduced two methods of

organ donation: living donation and deceased donation. Living donors may either donate via direct donation to a specific recipient or act as a non-direct “Good Samaritan” donor where the recipient is unknown. Kidney donors may also donate via paired donation, where a family member may wish to donate a kidney to a relative, but their blood type is incompatible. When this situation occurs, the related donor may instead donate to a nonrelated recipient in exchange for a kidney from a family member of that recipient, resulting in a “kidney swap.” The second method is deceased donation. Deceased donors may be considered either brain dead, characterized by no brain stem function, or experiencing circulatory death. Mulligan noted that while the number of organ transplants from deceased donors is growing, there is still a shortage of all solid organs.

OPTN, which maintains the national transplant list, plays an important role in living donation by maintaining quality standards and requirements through guidelines for donor evaluation and informed consent. It also provides training for the personnel in living donor programs. Together, Mulligan noted, OPTN and UNOS maintain a national database of available organs and the transplant waiting list and help to distribute organs equitably based on a set list of matching criteria, such as medical urgency, blood type, organ size, waiting time, and geographic distance. Mulligan discussed the survival rates for transplant patients. Table 2-1 highlights the survival rates for patients and grafts for all organ types 1 year after transplantation. Using OPTN data from 2015–2019, Mulligan discussed how despite 70–80 percent of patients having a high-performance status1 across all organ types, few are able to return to income-generating work. He noted that when looking at long-term data, such as 3 and 5 years after transplantation, the outcomes are similar: a strong majority of patients in all organ transplant types report good quality of life (QOL), but at 5 years after transplantation, 40–60 percent still have not returned to work, with kidney patients being the most likely and lung patients the least. Mulligan explained that 16 to 27 percent of patients do not have a reported performance status at 5 years after transplantation and beyond, meaning that while it is known whether these patients are still living, their QOL and return-to-work status remain unknown. Mulligan concluded by stating that

___________________

1 Performance status is a numerical rating of a patient’s ability to perform normal activities, including the ability to care for oneself (getting dressed, eating, and bathing) and to engage in more vigorous activity (cleaning a house, working at a job). The Karnofsky scale (100–0) is widely used. A normal score is between 80–100 percent (see Karnofsky et al., 1948).

| Kidney | Liver | Heart | Lung | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Survival (%) | 96 | 94 | 91 | 89 |

| Graft Survival (%) | 94 | 92 | 90 | 89 |

| Return to Work (%) | 31 | 21 | 21 | 14 |

| Normal QOL (%) | 75 | 72 | 80 | 70 |

NOTE: Normal QOL is defined by a Karnofsky score of 80–100 percent.

SOURCES: Adapted from David Mulligan presentation, March 22, 2021. Based on Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) data, including transplants from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2019.

while solid organ transplants have become increasingly successful, the rising rates of solid organ diseases in the United States is contributing to greater morbidity, mortality, and need for transplants.

DISPARITIES IN TRANSPLANTATION RECOVERY AND SURVIVAL

Tanjala Purnell, associate director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity and Urban Health Institute, has conducted extensive research on topics such as racial, ethnic, and wealth disparities in transplant recovery and survival. She framed her talk by stating that many factors contribute to differing transplant survival rates, such as age, body mass index, and etiology, as discussed in Chapter 3; but she said many social factors also contribute to whether transplant outcomes are positive or negative. She discussed the extensive benefits of transplantation, such as increased life expectancy, better QOL, maintaining independence, and the ability to return to work (Purnell et al., 2013). Purnell emphasized that the benefits, however, are not equal for all transplant recipients. Racial and ethnic disparities in heart transplant outcomes exist: Asian Americans have the highest graft survival rates, while African Americans have the lowest (Morris et al., 2016). Poverty levels and sex are also indicative of transplant outcomes, specifically graft survival. When examining 5-year kidney transplant outcomes, data show no significant difference in graft survival for men and women who live in wealthy neighborhoods, but as poverty levels increase, women are more likely to experience graft failure (Purnell et al., 2019). Nevertheless, kidney transplant outcomes tell an encouraging story. Purnell et al. (2016b) con-

ducted a study of racial disparities in kidney transplant outcomes spanning two decades and found increasingly similar survival rates between African American and White patients.

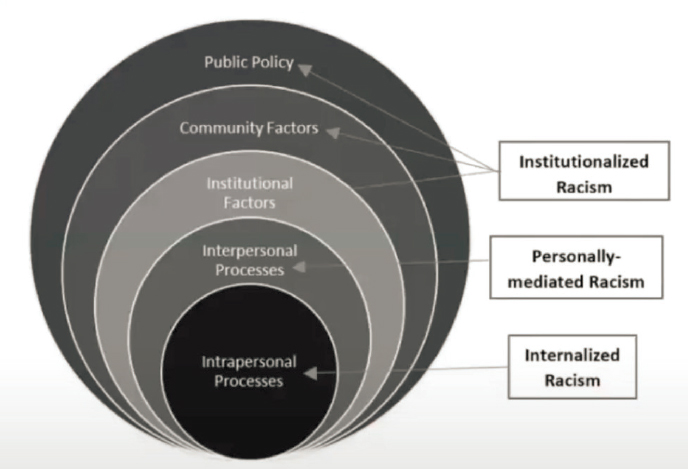

To understand racial, ethnic, and economic disparities in transplant outcomes, Purnell emphasized that examining the root cause is key, and stated that disparities exist because of multiple factors, including systemic racism. Arriola (2017) proposed a model of different types of racism experienced by African American transplant recipients, including internalized racism, personally mediated racism, and institutionalized racism (see Figure 2-1). Institutionalized racism is the largest portion of the model, presenting as institutionalized factors, community factors, and public policy. Purnell indicated that structural racism is another form and defined it as the mechanisms by which societies foster racial discrimination through systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and criminal justice that reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources (Bailey et al., 2017). She showed data from the Baltimore City Health Department (Barbot, 2014) as an example

SOURCES: Tanjala Purnell presentation, March 22, 2021; Arriola, Kimberly Jacob. “Race, Racism, and Access to Renal Transplantation Among African Americans.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 28:1 (2017), 35, Figure 1. © 2017 Meharry Medical College. Reprinted with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

of a practice called “redlining” (a form of residential segregation) and she explained that such institutionalized practices contribute to the economic and racial inequalities seen in organ transplant outcomes.

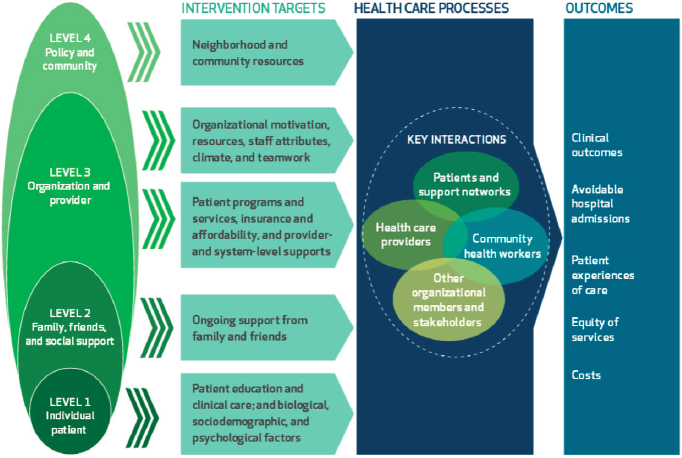

Purnell ended her presentation by posing the question of what needs to be done from a policy standpoint to achieve better transplant outcomes. She explained there is already general awareness of inequalities, such as patients from poorer neighborhoods experiencing worse outcomes, and so what is needed now is a targeted, multilevel approach to combat transplant inequalities. Purnell et al. (2016a) suggested intervention techniques designed to target individual patients as well as families, providers, and communities, ranging from patient education to programs to ensure affordability of care, to policy changes (see Figure 2-2). Her multilevel approach aims at improving clinical outcomes, avoiding hospital readmissions, improving the patient care experience, and ensuring equity of services. Despite a few encouraging statistics showing that the racial inequality gaps in transplant outcomes may be getting smaller, there is still a long way to go to combat racial, ethnic, and wealth disparities in transplant outcomes, she concluded.

SOURCES: Tanjala Purnell presentation, March 22, 2021; Purnell et al., 2016a.

PERSPECTIVES FROM ORGAN RECIPIENTS AND THEIR CAREGIVERS

An understanding of transplantation recovery and functioning cannot be attained by only looking at the transplantation system and policies or merely reviewing the science. The picture would be incomplete without the stories about the realities of life as told by people needing a transplant, people living with a transplant, or their caregivers. This section offers several first-person perspectives from organ recipients and then highlights a caregiver’s perspective and the viewpoint of a social worker who is paired with patients during and after a transplant.

Organ Recipient Perspectives

Five adults who had undergone organ transplantations shared stories about their journeys and what life is like now in the years after the procedure. They discussed the challenges of living with chronic diseases and the difficulties of managing life after organ transplantation.

Valen Keefer described her transplant journey beginning at the age of 10, when she was diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease (PKD), a hereditary disease that has taken the lives of many of her family members. Keefer said PKD caused pain and required many hospital stays as a child and a year-long stay in college. She finally had both kidneys removed, underwent 7 months of dialysis, and eventually received a kidney transplant at the age of 19. Keefer emphasized that she had a long road to recovery, which included taking 40 pills per day, dealing with side effects, and getting sick often because of her suppressed immune system. “While the transplant gave me a second chance at life, it didn’t cure my disease,” Keefer said. “Fourteen years following the kidney transplant, I got severely ill again,” she explained, “and after numerous recurrent sepsis episodes and daily antibiotics, I needed a lifesaving liver transplant.” Receiving an organ transplant is a singular event that does not translate into being fine once the procedure is over, she noted, and it requires dedication and resilience and is quite exhausting, both physically and mentally. “I’ve been a patient my whole life,” Keefer continued, “not knowing how I’m going to feel day to day. A fever or single lab number being off could lead to hospital stays.” She stressed the difficulty of being in her late 30s and still unable to maintain a full-time job, but added that she strives to take the best care of her health she can in order to be a contributing member to society, in gratitude to organ donors, and as an advocate for the transplant community.

Dawn Edwards introduced herself as a kidney transplant patient; she had kidney disease for 29 years and underwent a transplant in 2003 after 10 years on dialysis. Her journey was difficult from the start, she said. She was released 5 days after receiving her transplant, but had to go back daily for routine infusions. Then, 10 days later, she had her first rejection episode, which was “completely frightening,” but doctors were able to control it. During that episode, they discovered that she had acquired cytomegalovirus (CMV) from her donor. In addition to surgery recovery, Edwards shared that she also had a lot of stomach and intestinal problems from CMV. She described the first 3 years after transplantation like a roller coaster, and she was often in the hospital with either colitis or a rejection episode. But, she said, she always thought she would go back to work when the 3 years of disability benefits were up, so she had to focus on getting better in that time. She acknowledged that she could not return to her previous job because of the physical demands, so she thought about how to reinvent herself. Still, throughout this time, she continued to have episodes that made her recovery very difficult. She experienced side effects from anti-rejection medications, such as osteoporosis, which led to a broken hip that needed to be replaced after stepping off a curb one day. Edwards said that things started to settle down after the third year, and she was lucky to be offered a position within her end-stage renal disease (ESRD) network as her disability benefits ended. She attempted a trial period at the position; she still had occasional hospitalizations, but it went well, and her employer was very understanding. “I think disability for people with kidney transplants needs to be individualized,” Edwards stated; “it can’t just be the recovery from journey in and of itself.” She added that many patients would feel more comfortable if they did not have the pressure of needing to go back to work after that 3-year period or risk losing their health care coverage.

Stephanie Hoyt-Trapp was diagnosed with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, an advanced form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, about 10 years ago. Six years ago, she explained, she had to have a transplant because her liver had essentially ceased functioning. She was forced to stop her practice as a clinical psychologist and had just adopted an infant a few years prior as a single parent. She had many responsibilities but suddenly could not handle any of them and had to go on disability. “Getting a transplant was obviously the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” Hoyt-Trapp said. “Prior to the procedure I was very upbeat and positive that things were going to be okay.” She went on to say that she had thought she would return to her normal life, but when she did not, it was a huge turning point. Separate from the physical challenges,

she explained, her biggest challenge was her level of depression. She tried going through rehabilitation, but it did not help, and being unable to work, she said it felt like she was not doing anything of value. Finally, she shared, just recently she was asked to participate as a subject-matter expert on a research grant related to pain and cirrhosis. She said the work has allowed her to feel useful, use her brain, and have a valued opinion. “Having that sense of worth does a lot to help you get through this,” she added.

Sharing her perspective as a lung transplant recipient, Fanny Vlahos introduced herself as a licensed attorney, as well as many other roles including mother, who was born with cystic fibrosis (CF), a disease that mostly affects the lungs and pancreas. When she was born, the life expectancy for someone with CF was 14, Vlahos shared, but she recently celebrated her 40th birthday. She acknowledged that she is here today because she received a lifesaving double lung transplant 9 years ago. While she was fortunate and only mildly affected with CF for most of her life, she contracted pneumonia while pregnant and went from 130 percent lung function to needing a lung transplant in just 14 months, receiving new lungs when her baby was 10 months old. When thinking of going back to work, Vlahos explained, she had to consider her weekly doctor appointments, routine procedures, dozens of daily medications, and sensitivities to things in the environment that could compromise her suppressed immune system. She knew the legal community could not be as flexible as she needed, and had to stop her career and become a stay-at-home mom. Throughout her recovery, she endured both routine complications and near-fatal setbacks, with numerous gastrointestinal complications due to anti-rejection medications. Some days, Vlahos said she feels strong and ready to conquer the world, and other days, she feels her body is failing her, emphasizing that both the physical and mental stressors that come with this life are now her new normal. While her family has been with her through this entire journey, she pointed out that it is difficult for others—especially hiring managers—to understand her circumstances, because she looks “healthy” on the outside. But, living as a transplant patient has no finish line, and she said it is more than a full-time job to maintain her health. She wishes that employers would consider her value as a competent attorney with two law degrees, not as a liability for being an organ transplant recipient.

Robert Montgomery is a transplant surgeon at the New York University Langone Medical Center who also underwent a heart transplant. He has had a genetic heart disease, familial dilated cardiomyopathy, his whole life, but it became progressively worse. Though he was diagnosed early in his

career as a resident, he was able to continue for years as a transplant surgeon. In 2018, his condition acutely worsened, and he became very ill, ending up in the ICU in an urgent situation. He noted that he was lucky to receive a heart, but his donor had died from a drug overdose and had hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, requiring Montgomery to take additional medication to clear the virus from his blood. His recovery was fairly rapid, but he found himself facing new challenges that he did not anticipate, even after seeing thousands of transplant patients in his career. Most challenges were related to side effects from drugs—especially a tremor from one particular drug. While most patients just get used to it, he said, that is really not an option for a surgeon. So he spent a long time searching for an alternative drug that would not cause tremors. Montgomery reiterated the comments of other speakers, saying that you do not simply return to your normal life after a transplant. Instead, you take on a whole new challenge of being immunocompromised, which has significant risks and pitfalls. Fortunately, he admitted, he has been able to return fully to work as a surgeon and administrator, but he noted it has not been an easy journey.

Caregiver Perspective

For some patients, especially young children, the caregiver’s role can be just as challenging as the patients themselves. Melissa McQueen from Transplant Families shared her experience as a mother and caregiver when her son had to undergo a heart transplant as a baby. She shared that he nearly died right after birth and then was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy. McQueen’s son was eventually able to leave the hospital, but the treatments were not enough, and by the time he was 8 months old, he needed a heart transplant. Because they did not have a transplant center close to their home, they had to fly to Dallas, Texas, and were able to receive a heart shortly after the initial evaluation. Afterward, she said, he was a whole new baby, ready to tackle life. While they had hoped that would be the end of their journey, McQueen said in reality it was not. Many families do not talk about the difficult recovery, she said, and shared stories about some of the many stays in the hospital as he got older. He suffered from immune suppression problems and clostridium difficile infection and had to navigate many years of speech and occupational therapy. He also missed many milestones in early childhood. She said it was very difficult to get back on track after that and commented on the challenges that affect elementary-school aged kids, as well as adolescents, due to needing to adopt a strict adherence

schedule for medications and other demands. McQueen added that it takes a long time and support to get the pediatric patients to a place where they can truly grow and be successful.

Social Worker Perspective

Charlie Thomas, social worker at the Banner-University Medical Center Phoenix, explained that every U.S. organ transplant center certified by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is required to have a state-licensed, master’s level social worker. That way, he explained, every patient and family has access to a social worker, helping them navigate the process and outpatient posttransplant services. It begins a lifetime relationship with that patient and includes counseling, group work, and other services that are vital to their health and functioning.

Overview of Patient Challenges

Underscoring the realities related by the organ recipients and caregiver on the panel, Thomas presented a few of the major issues, including adjustment to chronic illness and ongoing treatment, relationship challenges, educational and vocational problems, crisis, chronic problem solving, as well as navigating difficult topics, such as end of life. Patients’ and families’ experiences are shaped most often by their insurance status, he added. Many have Medicaid or Medicare, making the government the largest payer of transplants in the country, but each insurance situation is different and often dictates how well patients do after transplantation. He shared findings from a 2001 study that, although QOL may improve for physical functioning, daily activities, and social functioning, various psychosocial problems confront the patient both before and after transplantation, with depression and anxiety being the most prevalent diagnoses (Engle, 2001). Other psychosocial problems included struggles with family roles and relationships, sexual dysfunction, return to work, adherence to a medical regimen, and anxiety about the possibility of organ rejection (Engle, 2001). Clinical outcomes were successful, Thomas said, yet mental and emotional health oftentimes suffered in the aftermath of the procedure. Caregivers are so important, noted Thomas, because after having access to so many medical experts and devices in the hospital, patients go home to a very different environment and need to manage their own care and treatment.

Difficulties Returning to Work

Thomas presented research on factors associated with returning to work. Paris et al. (1993) found that six factors were associated with return to work following a heart transplant:

- Physically able to work

- No loss of health insurance

- Longer length of time after transplant

- Education level higher than 12 years

- No loss of disability income

- Shorter length of disability before transplant

Thomas reported on another study that examined return to work after a heart transplant, which found associated factors to be age, length of disability before transplant, control over working conditions, and type of health insurance, including cost of medication (Meister et al., 1986). Of 47 patients, 32 percent returned to work, 25 percent retired, 7 percent were medically disabled, and 35 percent were “insurance disabled” (defined as fearing losing income and insurance by going back to work). Numbers from a study of kidney transplants were somewhat similar, with 57 percent of patients not working, but a high percentage (67 percent) with Medicaid reported that they were not working because they feared losing their health care benefits and not being able to afford immunosuppressive medications if they did go back to work (Markell et al., 1997).

Finally, Thomas shared recent results from a Swiss Transplant Consortium examining kidney, liver, heart, and lung transplant recipients: nearly 50 percent were employed by 12 months after transplantation, but the major predictor for this was pretransplant employment status (Vieux et al., 2019). He also commented that return to work was influenced by education level, depression levels 6 months after transplantation, and wait time in the employed group before transplantation—the longer unemployment was before transplantation, the longer it would take to be employed after.

DISCUSSION

McQueen began the discussion, asking others to highlight challenges recipients encounter when trying to manage their health, work, and family. Vlahos replied that the sheer volume of doctors’ appointments, treatments,

and medications really has a huge impact on daily life. She said that her transplant was not a cure for her CF; it gave her the gift of more time, but that time was not easily earned. Her transplant is at the forefront of all of her life decisions: where they live, where she works, what type of insurance they can get, or even where her husband works.

Regarding how the transplant has affected QOL, Edwards shared that her life has deteriorated. She ended up with other comorbidities, including bone diseases and early-stage colon cancer, and overall, it has affected her home life in a huge way, she said. While she can work somewhat, she has to carefully manage her schedule to ensure she does not do too much. She also struggles with mental health since her rejection episode and has been seeing a therapist. Keefer added that transplants come with many challenges before, during, and after the surgery. She also stressed the importance of the mental aspect and that it has not been emphasized enough in the field, and she advocated for more mental and emotional support for recipients. In response to other challenges navigating the system, Hoyt-Trapp highlighted the high levels of frustration and difficulty in trying to get services due to endless phone calls and paperwork. She said that while the initial recovery is coordinated through home health services, people have no centralized system available for different types of support or care after that. Making it even more difficult, she added, is that each state often has its own system, so things are not standardized. This is an issue for many patients who have to travel, or move, to other locations to obtain transplant services at specialized centers, which was also pointed out by Andrea DiMartini, professor of psychiatry and surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in her presentation (see Chapter 3).

Montgomery asked about the most difficult period following the transplant procedure, and McQueen commented that the transplant itself is similar to a short sprint, but the posttransplant experience is a long-distance run. Her son had a feeding pump for 3 years and therapists for 4 years. While he is doing well now and in school, she recalled the first few years as very difficult. Vlahos added that recovery ebbs and flows. For her, the initial period was an incredible gift of being able to breathe on her own again. But several months later, she started suffering more severely from medication side effects, needed more surgeries, and depended on intravenous nutrition. In a final point, Montgomery noted the struggle is just getting started at 1 year after transplantation, but that is often where patients really start to feel a sudden void in services and support. He explained that transplant centers are held accountable for metrics up until 1 year, such as rates of

patient and graft survival, for the purposes of financing and reimbursement. Because of this emphasis, he said, that is where the health care financing flows, leaving less support for the longer-term recovery.

This page intentionally left blank.