3

Organ Transplantation and Disability in Adults

Many speakers described organ transplantation as a complex, lifesaving treatment that begins prior to the transplant and continues with many transitions and recovery periods in the months and years following. This chapter begins with summaries of Session 1 presentations and discussion, which addressed the clinical conditions that are associated with transplantation in adults and the consequences for health and function. Following those clinical overviews are summaries of Session 5A presentations and discussion in which speakers focused on physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning in adults after organ transplantation.

CLINICAL CONDITIONS AND CONSEQUENCES FOR HEALTH AND FUNCTION

In the first session, speakers discussed the most common types of solid organ transplants in adults—kidney, liver, lung, and heart—highlighting the causes of the end-stage organ disease, methods for estimating posttransplant survival, and statistics on survival and recovery outcomes across various patient groups. In addition, the presentations and panel discussion explored various factors that are associated with survival, recovery, and functioning in these transplant patients.

Kidney Transplantation

Dorry Segev, professor of surgery and epidemiology and associate vice chair of the Department of Surgery at Johns Hopkins University (JHU), discussed the prevalence of CKD and ESRD. CKD is the most common form of solid organ disease, affecting 37 million U.S. adults, 9 in 10 of whom may be unaware of it (CDC, 2021). All patients on the transplant waitlist are given an EPTS, a numerical score used to allocate donor kidneys. EPTS scores are designed to predict survival rates based on a variety of factors, including age, number of years on dialysis, presence of diabetes, and whether a candidate has had a prior solid organ transplant. Data published by the OPTN from deceased donor adult kidney transplants in 2008–2018 show that patients with an EPTS score of 0–20 percent had a 90 percent survival rate at 10 years after transplantation, whereas those with a score of 81–100 percent had only a 40 percent survival rate (OPTN, 2020a).

Donor factors are also important in evaluating transplant outcomes, as the quality of the donor kidney also largely impacts survival rates, Segev said. Donors are evaluated based on the kidney donor risk index (KDRI) and the kidney donor profile index (KDPI); KDRI values are calculated to determine the KDPI. Donor characteristics used to calculate the KDRI are age, height, weight, ethnicity, history of hypertension or diabetes, cause of death, serum creatinine, HCV status, and donation after circulatory death status. Similar to EPTS scores, the KDPI is also measured on a scale of 0–100 percent, where lower percentages indicate better graft survival rates. Data from 2008 to 2018 show that patients receiving a kidney with a KDPI of 0–20 percent had a graft survival of 60 percent at 10 years after transplantation, whereas those receiving a kidney with a KDPI of 86–100 percent had a 10-year graft survival of only 30 percent (OPTN, 2020b). As discussed by Mulligan, organs of all types are in short supply, including kidneys. Segev explained that the overall discard rate of kidneys due to poor KDPI is about 30 percent, whereas 70 percent of kidneys with high KDPI are deemed unfit for transplant (Bae et al., 2016).

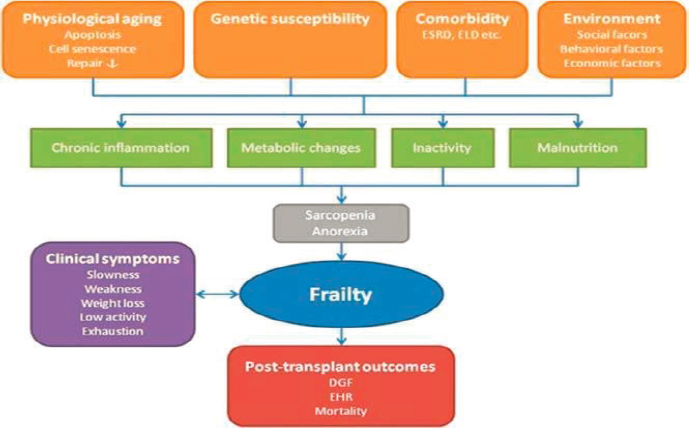

Another factor strongly impacting kidney transplant survival rates is frailty, Segev said. The American Society of Transplantation has not set an upper age limit for transplant consideration, so patients with CKD at any age can be evaluated. However, Segev noted, frailty, disability, or dependence are associated with poor outcomes. Frail patients are 40 percent less likely to be added to the waiting list, and those who do make it onto the list are 32 percent less likely to ever receive a transplant and 1.7 times more

likely to die waiting for a kidney (Haugen et al., 2019). Poor outcomes associated with frailty also include increased risk of mortality and early hospital readmission, increased risk of delayed graft function, and higher incidence of delirium (Garonzik-Wang et al., 2012; Haugen et al., 2018; McAdams-DeMarco et al., 2013a,b).

Segev discussed contraindications that may exclude eligibility for transplant. For example, absolute contraindications include active malignancy, acute infection, or vasculitis. Relative contraindications are cardiopulmonary disease, vascular disease, or uncontrolled psychiatric disorders. Other medical contraindications include bone disease, diabetes, hypertension, or anemia. However, Segev noted, all contraindications are evaluated case by case. When investigating cause of death after transplant, many of these contraindications are often present. Segev explained that 30–40 percent of deaths in kidney transplants are due to cardiovascular disorders, such as hypertension and diabetes, while 20–30 percent are due to infections, and an additional 20–30 percent are due to malignancy.1 Segev concluded by highlighting that the heterogeneous nature of CKD patients leads to a variety of outcomes. Factors such as patient EPTS scores, donor KDPI scores, frailty, and medical contraindications all contribute to whether a kidney transplant will be successful.

Liver Transplantation

Shari Rogal, transplant hepatologist at the Pittsburgh Veterans Affairs Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion and assistant professor of medicine and transplant surgery at the University of Pittsburgh, began by sharing statistics about the prevalence of liver disease among U.S. adults. It is the 12th leading cause of death, and hepatocellular carcinoma, commonly known as “liver cancer,” is the fastest growing cause of cancer death (Siegel et al., 2018). Consequently, she noted, the number of liver transplants per year is increasing and the patient population is older and sicker. Rogal shared data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) showing that in 2010, 11 percent of liver transplant recipients were over the age of 65, but that number doubled to 22 percent in 2020 (SRTR, 2018). She added that OPTN data show trends indicating survival rates can be predicted based on a patient’s MELD score at the time of transplant: lower scores are predictive of a better chance of survival. Patients with a MELD

___________________

1 Data courtesy of Dan Brennan, Johns Hopkins Medicine.

score below 15 at time of transplant have a 5-year survival rate of 84 percent, whereas patients with a score over 35 have a 5-year survival rate of about 74 percent (Kwong et al., 2020). As the population of liver transplant patients is aging, data also show that survival rates depend on age at transplant, she said. Data from Kwong et al. (2020) show that patients over 65 have a 5-year survival rate of 73 percent, whereas the 18–34 and 35–49 age groups both have a 5-year survival rate of 84 percent.

As the population makeup of liver transplant patients is changing, the causes of liver disease, or etiology, are changing as well. While 2.4 million people have liver disease associated with HCV, this number is decreasing (CDC, 2020b; Wong and Singal, 2020). Rogal explained that as HCV has become curable, those with HCV on the transplant waitlist are decreasing, while those on the list due to both alcohol use disorder and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are nearly double the rate of HCV patients (Wong and Singal, 2020). Etiology is also a good indication of graft survival; patients with hepatocellular carcinoma have the poorest transplant outcomes, and those with HCV or cholesterol disease have significantly higher survival rates (Kwong et al., 2018). However, Rogal noted, the statistics are not all bad, citing a study that showed liver transplant survival rates remain extremely high, with 86 percent still alive at 1 year after transplantation and 72 percent at 5 years after transplantation (Kwong et al., 2018). The study also showed that the number of living donor transplants is increasing. While these are still a small percentage of total liver donations, Rogal explained that because donated livers are allocated based on disease severity and the sickest patients typically receive deceased donors’ livers, the increase in living donors may indicate that more patients are receiving livers before extensive disease progression.

While survival rates for liver transplants are high, functional status remains relatively low 1 year after transplantation. Rogal shared that many patients report increases in physical distress, and more than half report limitations in the kind and amount of work they are able to do. Additionally, one in three patients is prevented from returning to work or school. A 12-year follow-up study showed many patients had no functional improvement at all (Ruppert et al., 2010). Rogal noted that while transplants may cure conditions such as liver cancer or metabolic diseases, they will not cure many underlying problems, whether they be physical, mental, or personal. Conditions such as diabetes, chronic pain, substance abuse disorder, depression, or financial problems are all obstacles that will remain after transplantation, and she added that some of these persistent problems, such

as depression or chronic pain, may play a role in survival. Rogal noted that patients who have a history of depression have lower survival rates, and those who have been prescribed opioids for chronic pain are also less likely to have positive transplant outcomes. Approximately 80 percent of cirrhosis patients report experiencing chronic pain, and half of those are prescribed opioids for pain management (Rogal et al., 2015). Additionally, evidence suggests that higher doses of opioids at the time of transplant are associated with decreased survival rates (Randall et al., 2017).

Finally, Rogal ended by emphasizing that every patient is different. Despite many ways to predict survival rates, such as MELD score, age, and etiology (strong indicators of positive outcomes), patients have many physical, mental, and personal reasons that could lead them to need a liver transplant, such as substance abuse disorders or diabetes, that are not cured solely by transplanting the organ. She pointed out that as the prevalence of liver disease continues to rise in the United States, the number of patients presenting with more severe disease at the time of transplant, coupled with high survival rates, is leading to more people experiencing disability and decreased functional status after transplantation.

Lung Transplantation

Lung transplants in the United States are also rapidly increasing. In 2019, a record number of candidates were added to the waitlist, and the number of transplants performed continues to grow each year (Valapour et al., 2021). Erika Lease, transplant pulmonologist at the University of Washington, explained that the number of lung transplants in the United States is growing, particularly the number of patients undergoing a double lung transplant. Data from the SRTR show that lung transplants have nearly doubled in the past decade, from 1,500 in 2008 to almost 3,000 in 2019 (Valapour et al., 2021). While the majority of recipients are age 50–64, the number of patients over 65 is growing.

Lease explained that lung transplant patients generally belong to one of four major disease categories: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary fibrosis, CF, or pulmonary hypertension. COPD, a slow and progressive disease commonly attributed to smoking, is one of the most common forms of lung disease for which lung transplantation may be indicated; because of the slow nature of the disease, many patients are over the age of 60 and account for a large proportion of elder recipients (Chambers et al., 2019; Devine, 2008). Pulmonary fibrosis, however, is a

common reason for lung transplant in older patients as well; patients generally have rapidly progressing disease and are typically transplanted within a few years of diagnosis. Pulmonary hypertension is another form of lung disease; blood vessels in the lungs become narrowed and can often lead to heart failure. Finally, the small portion of younger transplant recipients often suffers from CF, a lifelong genetic disease that leads to accumulating lung clogging and damage. Lease explained that these patients have the best survival rates, at almost 10 years, likely due to younger age at the time of transplant and lack of comorbidities.

Despite strides in the field of surgical techniques and posttransplant care, lung transplant long-term survival rates have not changed much in recent years. Lease explained that 10–15 percent of recipients will not survive the first year after transplantation and just under 50 percent will survive to 7 years. Since 1992, the median survival rate has only increased from 4.7 to 6.7 years (Chambers et al., 2019). Survival rates do differ depending on diagnosis and presence of comorbidities. While the median survival rate for CF patients, 9.9 years, is likely due to younger age at transplant, pulmonary fibrosis and COPD patients have the worst survival rates at 5.2 and 6 years, respectively. Lease explained these are likely due to older age at the time of transplant and smoking-related comorbidities in COPD patients (Chambers et al., 2019). Lease cited a variety of posttransplant complications that can lead to lower survival rates, such as recovering from a major thoracic surgery and pretransplant lung disease, adjusting to immunosuppressive medications, or chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD), a progressive loss of lung function for which there is no effective treatment. Early transplant complications may arise, such as infection, which is the most common cause of death in the first year after transplant, or acute rejection. Patients are also at risk of later complications, many stemming from complications from the immunosuppressive medications, which can cause patients to develop comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and even cancer. Lease indicated that long-term medication use can also lead to kidney damage; some patients may even require a kidney transplant. However, the biggest issue in later complications is CLAD, which Lease described as the greatest contributor to morbidity and mortality after the first year following transplant and showed that 43 percent of patients will have reported some kind of lung function decline by 5 years after transplantation (Valapour et al., 2021).

Lease concluded by emphasizing that the field of lung transplantation is constantly evolving, and survival is slowly improving. Survival rates can

vary greatly depending on etiology, age, and comorbidities, but despite increasing survival rates, patients have to navigate a new set of challenges, including changes in QOL, functional status, and comorbidities that often result in the need for frequent medical care.

Heart Transplantation

One in four deaths in the United States is attributed to heart disease, claiming the lives of more than 650,000 Americans annually (CDC, 2020a; Virani et al., 2020). Hannah Valantine, professor of medicine at Stanford University, began by outlining the numerous indications that may warrant a heart transplant, such as refractory cardiogenic shock, recurring left ventricular arrhythmias, and end-stage congenital heart failure (Alraies and Eckman, 2014). In essence, these patients have extensive disease that has been unresponsive to multiple therapies, are unable to carry out everyday activities, and may even require assistive devices, such as an inter-aortic balloon pump. However, more than 80 percent of heart transplants are due to just two common conditions: ischemic cardiomyopathy and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. The former, commonly known as “coronary artery disease,” has been responsible for 32.4 percent of heart transplants over the past decade; the latter, or heart failure without significant blockages to the coronary arteries, resulted in just over 50 percent of transplants (Khush et al., 2019). Valantine also noted that the number of patients bridged with mechanical support, or requiring mechanical circulatory assistive devices before transplant, is increasing. While only one-quarter of patients required a bridge to transplant in 2005, more than half did in 2017 (Khush et al., 2019). She explained that these patients requiring mechanical assistance are less likely to be able to fully rehabilitate and regain maximum function after transplantation.

As with all solid organ diseases, survival rates are largely dependent on etiology. Risk factors for mortality at both 1 year and 5 years after transplantation are similar, said Valantine, and include recipient age, body mass index, and kidney function as measured by creatinine levels. Survival risk factors also depend on the health of the donor, including age, cigarette use history, and donor–recipient predicted heart mass match (donor and recipient must be similar in weight) (Khush et al., 2019). Kidney function before transplantation is also particularly important due to the need for immunosuppressive medications after transplantation. Similar to lung transplant patients, she explained, heart transplant patients require many medications

that put them at increased risk of kidney failure; 6.7 percent have severe renal dysfunction 1 year after transplantation and 15.7 percent 5 years after transplantation (Khush et al., 2019). Despite all of the necessary medications heart transplant recipients require, some will still experience rejection. Those who do, defined as having at least one acute rejection episode treated by an anti-rejection agent or being hospitalized for rejection, still equal 12 percent (Khush et al., 2019). Valantine explained that rejection is often treated with high-dose corticosteroids and other drugs that can put patients at risk for infection and require long periods of rehospitalization.

Despite the risk of complications, survival rates for heart transplant recipients are encouraging. Overall survival 1 year after transplantation is 91 percent, and it is 75 percent at 5 years, translating to median overall survival rates of 11.4 years for men and 12.2 years for women (Khush et al., 2019). Functional status and QOL after transplantation are also promising, Valantine added. She explained that 75 percent of patients report being able to carry out normal activity and 39 percent have returned to work 5 years after transplantation (Khush et al., 2019).

Valantine also discussed the three most common causes of death: malignancy, graft failure resulting in heart failure usually attributed to rejection, and cardiac allograft vasculopathy, a progressive blockage of the coronary arteries to the graft; she indicated that data from 1995 to 2018 show these three causes were responsible for 19.6 percent, 24.4 percent, and 12.4 percent of deaths, respectively. Valantine was optimistic about the median survival rate for heart transplant recipients being 11.6 years, and that as many as three in four are able to maintain good QOL and functional status. However, she added, a small percentage still battle disabling rejection and infection.

DISCUSSION

Paul Kimmel, program director at the Division of Kidney, Urologic, and Hematologic Diseases at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, moderated a discussion with the speakers from the first session. Reflecting on the challenges of returning to work, each speaker underscored that transplantation is only a treatment, not a cure. Moreover, recovery is extensive and a positive outcome is not always guaranteed, they cautioned. When thinking about posttransplant outcomes and disability, Kimmel asked why patients may enjoy good QOL but remain unable to return to work. Several experts agreed that a variety of factors are

responsible for this disparity, such as the aging population of transplant recipients, mental health issues, and lack of employee protections. The lack of mental health care and poor social determinants of health in the United States also prevent many patients from returning to work, not because they are physically disabled but because they are not receiving adequate mental health and other psychosocial supports, as many workshop speakers pointed out. Underscoring this point, Segev implored clinicians to ask about emotional well-being rather than only focusing on physical health. He stressed the need for increased funding for mental health studies, while making the point that if only physical determinants of health, such as immunology and tissue engineering, are studied, that is all that will be known. Rogal also noted that patients who struggle with mental illness often turn to substance abuse, particularly alcohol and tobacco, which can also affect physical recovery and lead to poor outcomes. Finally, many patients do not return to work because of a lack of employee protections. Posttransplant care requires rigorous follow-up appointments that require time away from work. Purnell noted that hourly workers do not have the type of protections that salaried workers may have, such as the ability to take time off for these appointments. Many patients fear losing their disability benefits if they return to work, and hourly workers will not be paid while they take time off to attend medical appointments, leaving them without disability benefits or a paycheck. She added that labor laws and leave policies need to be examined and expanded to protect recipients from the fear of losing their jobs or benefits. Additionally, some may not be able to return to work due to unsafe working conditions given their new vulnerabilities. The fear of respiratory viruses or infection leaves many patients unable to return. Lease noted that many lung transplant recipients have experienced chronic allograft dysfunction after being exposed to respiratory viruses at work.

Kimmel posed a question about gaps in the available data, as transplant registries often lack functional data. David Mulligan responded that tracking long-term patient data lies largely on the shoulders of the transplant center and he suggested that patient self-reporting may lessen the burden. Furthermore, patients may relocate to posttransplant and transition care elsewhere rather than continuing care at their original transplant center. Several speakers identified a need to use new technology to report data, particularly in a way that makes it easy for patients to self-report data. Valantine also pointed out there are data gaps related to the social determinants of health, echoing Segev’s previous comments by emphasizing “what gets measured gets done.” Data on race, wealth, sex, and mental health are lacking because they

are not always being measured, she argued. This again highlights the need to focus more on the “soft sciences,” not only when treating patients but also while collecting data.

ASSESSING PHYSICAL, COGNITIVE, AND PSYCHOSOCIAL FUNCTION IN ADULTS AFTER ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION

As many speakers noted, the transplant journey does not end once the procedure is completed. Transplantation recovery is complex and thus answering questions regarding returning to work depend on many different factors. In Session 5A regarding adult physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning after transplantation, speakers described methods of assessing patient functioning and presented research findings on short- and long-term effects of transplantation on functioning and QOL. A panel discussion further explored the topic of impairments that can lead to disability following an organ transplant.

Physical Functioning

In order to talk about physical functioning after transplantation, a discussion about what happens to the body before transplant is necessary, said Jignesh Patel, medical director at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Due to end-stage organ disease, many patients end up with a physiologic state that results in significant disability. Patel defined “frailty” as a state of increased vulnerability to physiologic stress—distinct from aging, comorbidity, or disability—and noted the difficulty in quantifying frailty due to the lack of a gold standard assessment tool. Frailty is a common problem in organ transplants, he said, because of the nature of end-stage organ disease, and it manifests as decline in physical, psychosocial, and cognitive function. Patel indicated that the “Fried Criteria”2 is the most extensively validated current tool and presented several studies that demonstrated that frail kidney transplant patients are at increased risk of poor outcomes. He noted that frailty is associated with more than 50 percent odds of a 2-week or longer length of hospital stay, almost twice the risk of delayed graft function, and more than twice the risk of mortality (Garonzik-Wang et al., 2012; McAdams-DeMarco et al., 2015, 2017). Looking closer at mortality associated with

___________________

2 Fried’s frailty model consists of five criteria—weight loss, exhaustion, low physical activity, slowness, and weakness—that are used for identifying frail older adults (Fried et al., 2001).

frailty after transplant across various organs, he emphasized that regardless of the organ type, being classified as frail prior to the transplantation nearly doubles the risk of mortality. The challenge, Patel continued, is transitioning a patient who has end-stage organ disease into a physically functioning state after transplantation. At an American Society of Transplantation conference convened on frailty, participants developed several concepts identifying it as common in patients (Kobashigawa et al., 2019). Patel explained that the conference noted that frailty affects mortality on the waitlist and in the posttransplant period. Participants discussed optimal methods to measure frailty, but these are yet to be determined or agreed upon. Patel also noted that interventions to reverse frailty are shown to vary among organ groups but so far appear promising. He summarized what happens in frailty and noted that the components include a range of factors across body systems, genetics, and the environment (see Figure 3-1). Age is certainly an important component, he acknowledged, as the greatest increase in demand for transplantation is seen by those above age 65, regardless of organ.

To address the issue of pretransplant frailty, Patel noted that attempts at prehabilitation have been made to see if patients can get stronger before the procedure, but these have shown limited efficacy. The most

NOTE: DGF = delayed graft function; EHR = early hospital readmission; ELD = end-stage liver disease; ESRD = end-stage renal disease.

SOURCES: Jignesh Patel presentation, March 23, 2021; Exterkate et al., 2016.

common intervention was exercise, but it has a large range in dropout rates—5–50 percent. Overall, exercise improved physical function, but the gains were modest compared to baseline level of impairment. Patel also described a clinical trial conducted by Kobashigawa et al. (1999), which measured exercise rehabilitation after heart transplant. Certain biomarkers improved following the intervention, he said, and other studies have shown that cardiac rehabilitation after a heart transplant was associated with significant decline in rehospitalization rates (Bachman et al., 2018). Similarly, in lung transplantation, a supervised exercise training intervention in the first 3 months after transplant was associated with increased functional capacity—at 3 months and even 1 year afterward (Langer, 2015). In longer-term studies, nearly half of patients reported no functional disability—but those who did cited more clinical symptoms, depression, and other comorbidities. They were more often older, female, less educated, and unemployed (Grady et al., 2007).

Measuring physical functioning continues to be a challenge, but new technology is becoming more commonly used and integrated into monitoring. Patel highlighted activity trackers or wearable devices that offer feedback to adjust activity in near real time—something that looks promising but is still being evaluated, he added. Essentially, physical functioning after an organ transplant is highly dependent on pretransplant state. Frailty is very common, said Patel, and despite some efforts to address frailty prior to transplant, most efforts thus far have focused on the posttransplant phase.

Cognitive Functioning

Aditi Gupta, associate professor of medicine at the University of Kansas Medical Center, opened by sharing that an inspiration for her research career was a patient who mentioned the brain fog they suffered from disappeared following a transplant. Gupta pointed out that cognitive impairment is common; she shared a study of patients on dialysis that found up to 87 percent have some form of cognitive impairment, with just 13 percent having normal cognitive function (Murray et al., 2006). Cognitive impairment influences kidney transplant eligibility, Gupta noted. She shared findings from her study that showed subclinical cognitive impairment is associated with a lower likelihood of being listed for a kidney transplant and a longer time getting to transplant (Gupta et al., 2019). Gupta explained that kidney transplant recipients have a high prevalence of cognitive impairment, regardless of age. However, despite this knowledge becoming more widely available, she said

it is not currently the standard of care to measure cognition in pretransplant or posttransplant care, and most centers do not even have the resources to do so or screen for cognitive impairment.

Gupta stated that although many clinicians feel that they could reliably detect some type of cognitive impairment in their patients, this may not be the case. Gupta described a study showing that the clinicians’ perceptions of cognitive impairment in patients matched the “measured” cognition scores (using a standardized assessment tool) only about half the time (Gupta et al., 2018). The exact etiology of cognitive impairment is multifactorial but unknown, she explained. Ongoing studies are examining the possible role of anti-rejection medications, such as calcineurin inhibitors, which are potent vasoconstrictors and hypothesized to potentially decrease cerebral blood flow and affect cognition. Focusing more on the connection between CKD and brain abnormalities, Gupta said that it is well established, and the specific brain abnormalities that CKD causes are associated with cognitive impairments also seen in non-CKD populations. To understand these connections better, she shared a study that examined brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before, 3 months after, and 12 months after transplant and found that where blood flow in the brain was higher before transplantation, it decreased after transplant—even below the original baseline (Lepping et al., 2021).

Looking more broadly, Gupta discussed several longitudinal studies assessing change in cognition from pre- to post-kidney transplant. Not a lot of data are available, and research is ongoing, she said, but overall, all studies give the same message—certain domains of cognition do improve after transplantation, but overall cognition does not totally normalize. She highlighted one study that demonstrated improved logical memory, but no improvements in other areas of cognition after kidney transplant (Gupta et al., 2017). Gupta noted that preliminary data from cognition analysis studies correlated with brain changes detected in MRIs. She said short screening tests are not sensitive enough to appreciate the change in cognition, and current information is insufficient about which domains and which areas of the brain improve. Gupta explained that the current thinking is most of the chronic brain damage being measured happened before the transplant and is not completely reversible, but studies are still ongoing. Overall, she concluded that cognitive impairment is highly prevalent among transplant recipients but the field still needs better ways to assess cognition. She pointed out that mechanisms for underlying deficits in cognitive impairment vary among different solid organs, so findings from one organ to another should not be extrapolated. Finally, there are

not currently enough data to be able to predict posttransplant cognition scores based on pretesting.

Psychosocial and Emotional Functioning

Transplantation is not merely the singular event related to the surgery; it is a journey that begins before that, with discrete transition and recovery periods, said Andrea DiMartini, professor of psychiatry and surgery at the University of Pittsburgh. DiMartini explained that after patients are put on the waitlist, while waiting for a donated organ to become available, they may become sicker, with acute health crises and deteriorating physical health. Many patients maintain hope but still recognize the possibility that a transplant might not occur, which can result in great emotional stress. When patients receive an organ, there is an initial posttransplant period where they are elated to have received this second chance but then realize there is a lot of physical recovery to be achieved, which can be really discouraging, DiMartini said. They also may face the constant worry of organ rejection or rehospitalization and the stress of adjusting to powerful daily immunosuppressive medications. As they begin to adapt to their new lives and responsibilities, they also try to resume their previous life and may consider going back to work, creating a lot of potential stressors. The long-term maintenance phase, she added, may include chronic rejection, recurrent organ disease, or even a need for a second transplant, so stress may continue even many years later.

QOL is an important metric of physical and mental well-being, said DiMartini. Virtually all studies show that transplant recipients show some improvement in QOL, but the level is more comparable to others with chronic disease as compared to that of healthy people. In terms of mental well-being, DiMartini noted that the first year following transplant has shown mood and anxiety disorders, ranging from 20 percent for kidney recipients to as high as 60 percent for heart recipients (DiMartini et al., 2008). Anxiety specifically appears to be prominent in lung recipients, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can sometimes develop from the transplant experience. PTSD may cause avoidance of future appointments because of the anxiety that it triggers. The rates of onset of mental health disorders appear to follow a certain pattern after transplantation. She shared findings from Dew et al. (2001) that examined heart transplant recipients and found their first year was particularly stressful, which is expected, she said. Although the prevalence of depressive or anxiety disorders declined

over subsequent years, she noted that it then plateaued and began to increase again around 10 years after transplantation, perhaps at the time where patients begin to experience additional health problems. Certain mental health disorders are linked to poor medical outcomes, DiMartini stated. Depression is a primary example—it is associated with unhealthy physiologic changes, such as inflammation, lethargy, fatigue, poor sleep, and poor appetite. A meta-analysis showed that among transplant recipients across all organ types, those who had a pre- or posttransplant history of depression had significantly poorer survival rates and increased graft loss (Dew et al., 2015). She also highlighted a possible correlation in liver recipients between posttransplant depression and unemployment but noted that the temporal relationship between this linkage was unknown, and more research is still needed to determine its direction (Newton, 2003).

Strategies to Improve Mental Health Outcomes and Support Return to Work

DiMartini began by stating that clinical strategies that consider patients’ lives before transplant and that prepare them for transplantation during the pretransplant phase can help improve posttransplant outcomes. In addition to ensuring patients have sufficient social support, she emphasized the need to prepare patients for realistic expectations regarding physical outcomes and long-term functioning, with varying plans on returning to work, depending on each individual. She shared findings from Rogal et al. (2013) illustrating the importance of this early identification and treatment of mental health issues, where researchers found liver recipients who were given adequate antidepressant therapy had better survival rates than those with depression who were untreated. It appeared that adequate treatment may reduce mortality risk conferred by depression, she explained. DiMartini offered some interventions that clinicians can suggest to assist recipients in their quest to return to work (see Box 3-1).

In summary, DiMartini said, placing the strongest efforts into the first year after transplantation, where stress and rates of mental health disorders are high, and focus on mental health and recovery may help to maximize long-term outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Erika Lease and Shari Rogal moderated a discussion with the Session 5A speakers on the various methods for assessing and improving physical and

cognitive functioning in adult transplant recipients. Lease asked Patel how effective posttransplant interventions are for frailty and whether the improvements seen are sustainable. Patel responded that the data supporting interventions are strongest for heart transplants, where cardiac rehabilitation has been shown to significantly improve functional capacity, QOL, and cognition and translate into long-term benefits. Because of this, cardiac rehabilitation is now a routine part of care, but this is less so for other organs, where the evidence is less established. But Patel commented that the general changes resulting in frailty are common to all organ transplants, so presumably the improvements found from posttransplant cardiac rehabilitation would be applicable across other solid organs.

Lease asked Gupta whether patients can recognize cognitive impairment in themselves or if they must rely on a medical provider to identify and address it. Gupta said that the patients will generally feel it, likely sooner than a medical provider would notice, but it is subjective. She said the only way for providers to really identify cognitive decline is to conduct formal testing, which is less focused on an absolute score but instead

something to watch over time to see how it changes. Once the presence of cognitive decline or impairment has been established, Gupta noted that the success of the intervention will depend on the mechanism of the issue, as some will be more reversible than others. For example, in kidney disease, reasons could be related to the disease directly, even before transplantation, or cognitive decline could be because of calcineurin inhibitors or other immunosuppressive agents that constrict blood flow, but she said it is unknown whether they affect cerebral flood flow. Additionally, cognitive decline could be related to the surgical process, she said; kidney transplant surgeries are typically shorter and easier on the body, compared to heart or lung transplants, which are longer and cause more hypotension and postoperative delirium.

Numerous barriers to recovery are also related to psychosocial and emotional function, which can make it difficult for patients to resume their lives. DiMartini noted that if patients are not being screened for mental health problems, then it is difficult to pick up on how they are doing. Unless transplant recipients are asked appropriate questions about how they are doing emotionally, she said, it is easy to overlook those who are experiencing significant depression or anxiety. Providing patients with appropriate mental health treatment so symptoms are in remission before the surgery is important, DiMartini said. But, she added, this can be challenging because many patients travel out of state for transplant care. Obtaining mental health care can be particularly problematic either because the provider is located in a different state, which can be difficult with telemedicine regulations, or the provider is separate from the transplant program, which can make it hard for some patients to maintain regular appointments.

Lease also asked about comorbidities that arise from posttransplant treatment and if some are more common or more limiting than others. Patel responded that most are directly related to immunosuppression medication effects. For example, diabetes becomes much more prevalent in this population, as well as high blood pressure and obesity. Together, these comorbidities can certainly affect QOL and functioning. Gupta agreed on the importance of rehabilitation programs in the early posttransplant phases but commented that many patients who receive organ transplants do not have access to them. She highlighted many studies that show patients do really well mentally and physically in active intervention programs after transplantation, but when they end, things tend to return to the way they were before the research study. Therefore, some kind of longer-term maintenance program is needed, she said. DiMartini added that depression is a

significant comorbidity that can affect every area of life and functioning, including whether someone is taking recommended medications. She emphasized that inadequately treated depression in transplant patients can affect not only QOL but also survival. In one study, patients who were depressed were approximately 2.5 times more likely to die in subsequent posttransplant years as compared to patients who were not depressed (Rogal et al., 2013).

Impact of COVID-19 on Posttransplant Functioning

Lease asked all speakers whether they know what impact active COVID-19 infection has had on transplant recipients’ posttransplant functional abilities, directly or indirectly. Gupta replied, noting the differences between “active COVID” and “long COVID,” where patients suffer from fatigue and sometimes cognitive impairment for months afterward. Many questions remain about how these symptoms would intersect with posttransplant symptoms in a transplant recipient. Patel added that they do know mortality rates for transplants are very high at 20–25 percent for hospitalized patients. Emerging data show the vaccine may not be fully protective for transplant recipients (Boyarsky et al., 2021), which naturally is leading to anxiety for those who are feeling vulnerable. DiMartini also emphasized this point, calling attention to the anxiety and depression levels—even substance use relapse—by patients who are very concerned with getting infected and are afraid to leave the house. Lease agreed COVID-19 has significantly impacted early posttransplant management and care. She added that getting people access to physical functioning rehabilitation was extremely difficult with most of the programs closed during the previous year.

Final Thoughts on Changes to Improve Outcomes

In conclusion, Rogal asked each speaker to suggest changes to policies or other factors that could improve outcomes. DiMartini emphatically responded that insurance and access to care would be her focus areas, because she struggles to find mental health resources that are covered by insurance, no matter what location patients are in at the time. Patel agreed and added that access to physical rehabilitation in the early posttransplant phase is also critical. Investing in rehabilitation services is important, he said, because they can help reduce rehospitalization rates and comorbidities and improve survival and return-to-work rates.

__________________