4

Organ Transplantation and Disability in Children and Adolescents

While the majority of transplant patients are adults, hundreds of children undergo solid organ transplantation each year in the United States. Similar to Chapter 3, but addressing special concerns of children and adolescents, this chapter summarizes the presentations and discussions in Session 2 regarding the clinical conditions that are associated with the most common pediatric organ transplants and the consequences for health and function. This is followed by summaries of the Session 5B presentations and discussions in which speakers focused on physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning in children after organ transplantation, as well as the specific challenges that adolescents face.

CLINICAL CONDITIONS AND CONSEQUENCES FOR HEALTH AND FUNCTION

Session 2 speakers presented clinical overviews of liver and intestine, kidney, lung, and heart transplants in children and adolescents that highlighted the causes of the end-stage organ disease, methods for estimating posttransplant survival, and statistics on survival and recovery outcomes across various groups. In addition, the presentations and panel discussion explored various factors that are associated with survival, recovery, and functioning in these patients.

Liver and Intestine Transplantation

George V. Mazariegos, chief of pediatric transplantation at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, began with an overview of liver and intestine transplantation in children, noting that the number of pediatric liver transplants is approximately five times more than the number of pediatric intestine transplants each year. He said that the number of pediatric liver transplants has been fairly stable over the past decade, whereas the number of intestinal transplants is decreasing—primarily because of hormonal therapy improvements and other medical advances in the treatment of gut diseases. He indicated that a key trend is the ability to do technical variant liver transplants,1 which offers children an option that has reduced waitlist mortality, possibly eliminating it entirely. Retransplantation is fairly rare for liver recipients, he added, with just 10 percent needing one within 15 years. However, 15 percent of intestine recipients may require a retransplant within 5 years (Kwong et al., 2021). Mazariegos shared additional findings based on OPTN/SRTR data: more than 27,000 U.S. children are living with a functional allograft today, with liver and kidney transplants being the highest, compared to fewer heart recipients and significantly fewer intestine and lung recipients.

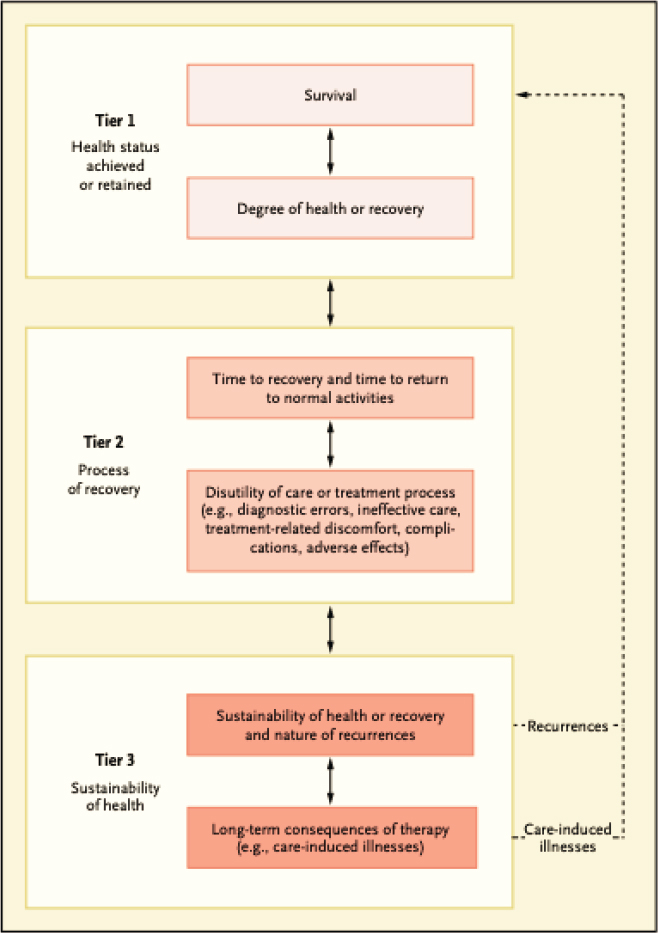

Before discussing the factors that can lead to liver or intestinal transplantation, Mazariegos reviewed a three-tiered hierarchy of outcome measures, a concept that can be applied to any chronic disease or therapy, allowing caregivers and families to understand the different tiers of care that can occur over the life cycle of a certain condition (Porter, 2010; see Figure 4-1). In the surgical transplant world, Mazariegos explained that patient outcome assessments most often address Tier 1, centering on survival. Tier 2 is focused on the process of recovery, the time it takes, and how well patients can return to healthy living. Tier 3 covers sustainability of health. This third tier asks whether the condition is successfully treated after transplantation, if disease recurs, and what long-term consequences of any therapy might be. If patients develop other diseases or need retransplantation, the cycle would start again.

To help understand how liver and intestine transplants may be similar or different, Mazariegos discussed what diseases lead to transplantation in children. For those requiring a liver transplant, the most common conditions are chronic liver disease and metabolic or genetic conditions, which together account for more than 50 percent of the indications for pediatric

___________________

1 Technical variant techniques use a partial liver graft to replace the role of a whole organ.

SOURCES: George Mazariegos presentation, March 22, 2021; Porter, 2010.

liver transplants in the United States (Squires et al., 2014). For those needing an intestine transplant, 70 percent of indications relate to loss of the intestine from surgical removal due to a condition such as necrotizing enterocolitis (Horslen et al., 2021). The other 30 percent are due to motility disorders, but systemic conditions leading to gut loss are generally rare (Horslen et al., 2021). In chronic liver disease, many of the associated comorbidities are attributable to malnutrition or liver failure and will improve following transplant. But in some children with metabolic disease, the ongoing systemic condition may not allow a complete return to normal even after transplantation, highlighting the ongoing systemic effect of the metabolic complications.

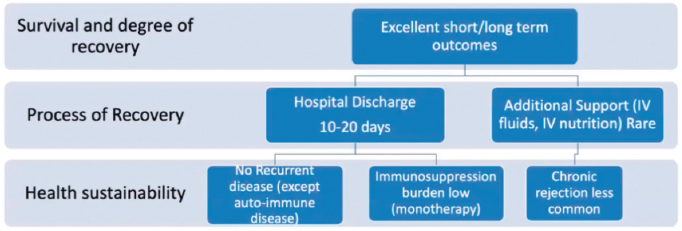

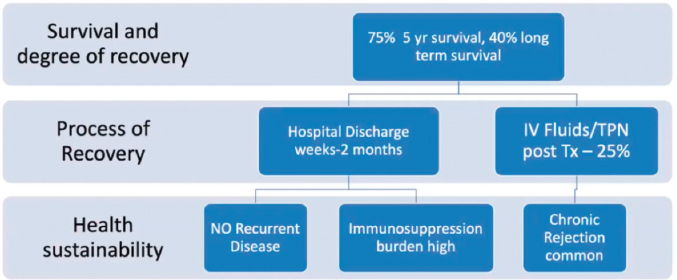

In terms of long-term outcomes, Mazariegos explained that liver transplant recipients fare significantly better than patients requiring intestine transplants. Only about 25 percent of liver recipients from deceased donors had graft failure after 10 years, compared to 40–60 percent of intestine recipients (Kwong et al., 2021). Most who received a liver transplant since 1989 still have their first allograft. Thinking specifically about liver and intestine transplants within the tiered outcome model (see Figure 4-1), he said the degree of recovery for liver transplant recipients is excellent, with good short- and long-term outcomes (see Figure 4-2). In comparison, pediatric intestine transplant patients have a more challenging survival and degree of recovery, shown in Figure 4-3. Survival is generally good compared to death from the significant morbidities of their disease, but only 40 percent of patients needing intestine transplantation have long-term survival.

In his concluding remarks, Mazariegos called for transitioning to a more holistic standard when viewing outcome metrics. He presented a study conducted by Ng et al. (2012) looking at liver transplants 10 years

NOTE: IV = intravenous.

SOURCE: George Mazariegos presentation, March 22, 2021.

NOTE: IV = intravenous; TPN = total parenteral nutrition; Tx = treatment.

SOURCE: George Mazariegos presentation, March 22, 2021.

after transplantation, which examined how the liver was functioning and what extra hepatic measures of an ideal outcome were present, including QOL. While most of the 10-year survivors had achieved most of the measures, only about one-third achieved all 13 of them. Marzariegos stated he believes liver and intestine transplants are best evaluated through an outcomes hierarchy to identify the distinct challenges children face through the transplant journey, as their cycle of care is measured in decades compared to years for adults.

Kidney Transplantation

Maria E. Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris, professor of pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, focused her presentation on kidney transplants in children and young adults. She first presented data from 2015 to 2018 showing the difference in causes of end-stage kidney disease by age. Children who are diagnosed young, especially less than 1 year old, she said, are more likely to have congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urinary tract. But in children diagnosed later, the causes are more likely to be glomerular disease or other conditions. She added that the incidence and prevalence of end-stage kidney disease in children have really remained stable in the United States. While adults typically have a 10-year survival rate of about 50 percent, children often fare much better, and have 10-year survival rates of 85–90 percent, an increase from the 70 percent range in the 1970s (Ferris et al., 2006).

Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris explained what it means if a child has end-stage kidney disease. Pediatric patients can have comorbidities, just like adults, but also may experience cognitive impairment, learning abnormalities, mood disorders, gastrointestinal disturbances, and even dental abnormalities. She added that cardiovascular disease plays a significant role in a child’s prognosis, and those who survive to their 30s and 40s may have the same cardiovascular risk as an 80-year-old. Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris indicated that the mental and emotional burden on these pediatric patients adds another challenge, as they often have low levels of employment in adulthood, low self-esteem, and diminished health-related QOL. In addition, she said that adolescents and young adults with chronic of end-stage kidney disease are at great risk of nonadherence to medication regimens and provider follow-ups. She explained that it is difficult for them to self-manage their disease in part because typical individuals do not reach brain maturity until their mid-20s, and the cognitive effects of end-stage kidney disease may delay full maturity. Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris presented on Gogtay et al. (2004), which measured brain activity in healthy controls compared to pediatric kidney disease patients and found that the latter had decreased activation in the parietal lobe and prefrontal regions of the brain. She said that these children may take longer to mature, and even at full maturity, they may not have formed all of their neural connections.

Once pediatric patients with chronic conditions, including those who have received a transplant, have transferred to adult-oriented care, Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris said, they often do not have a great deal of knowledge about their diagnosis and medications, are often nonadherent, and may continue to be dependent on their parents. Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris cautioned that when adolescent patients with chronic conditions are not prepared to self-manage their care as adults, they can experience adverse effects, including transplant rejection, death, graft loss, higher hemoglobin A1C scores in diabetics, and increased arthritis activity. Reporting findings from a study that measured transition readiness among adolescents and young adults (Zhong et al., 2018), she said that while many with chronic conditions succeed at mastering different parts of their condition along the way, it was not until they were in their 20s that they fully learned to self-manage their health. Thus, Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris noted, programs that teach patients about health self-management and focus on this transition are important. She described research that found adolescents significantly preferred learning about their health conditions from their parents or provider, as compared to the Internet, other patients, or written informa-

tion (Johnson et al., 2015). These preferences were associated with greater adherence to treatment protocols, self-efficacy, and transition readiness. See Adolescent Transitions to Adulthood After Transplantation below for additional information on this topic.

Lung Transplantation

Pediatric lung transplants are very rare, said Carol Conrad of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, with only 37 pediatric lung transplant centers around the world, mostly in North America and Europe. At her center in California, they perform three to five pediatric lung transplants each year. She explained the wide range in causes of end-stage lung disease, differing by the age of the child. CF is the most common reason in older children and teenagers, with an average of 58 each year worldwide. Infants are commonly referred for pulmonary hypertension, which often develops secondary to a cardiovascular malformation. Other causes include interstitial lung diseases from genetic mutations or rheumatologic disorders, but these types of disorders require very few lung transplants annually. Conrad presented a survival curve comparing rates between children and adults, with median survival for adults being 8.3 years and children 9.1 years. However, she did note that survival has been improving since 2010 (Hayes et al., 2019). When breaking down the data for children into more discrete age groups, she explained that younger children have better outcomes compared to adolescents. This is in part due to adolescents’ new sense of independence and poorer adherence to recovery treatments, Conrad said.

Conrad discussed how transplant centers estimate the level of impairment in a patient prior to transplantation through a combination of aerobic and mobility testing, muscle function, and assessment of physical activity level. However, many pediatric patients with lung diseases are unable to complete a 6-minute walking test because of their limited lung function, Conrad said. If their lungs are scarred or have limited blood flow, they are unable to increase their lung volume, leading to low oxygen levels. Conrad emphasized that optimal physical function and condition before lung transplantation contributes to better outcomes. She referenced studies in both pediatric and adult candidates that demonstrate that rehabilitation exercises before transplantation can lead to an improved exercise activity level and increase in the 6-minute walk distance (Castleberry et al., 2017). She said these gains are correlated with improved patient survival while on the lung transplant waiting list, fewer days on mechanical ventilation, and shorter stays in the ICU after

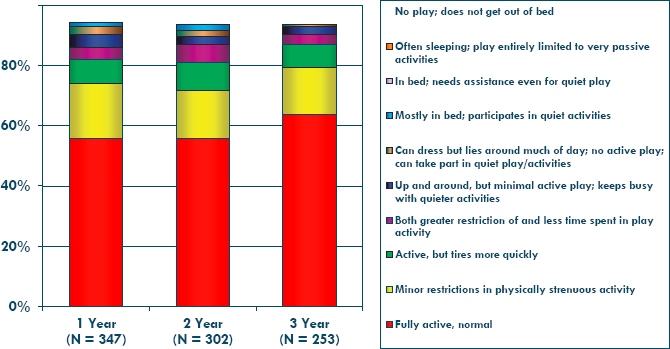

transplantation for both children and adults. Posttransplant complications can decrease from exercise training and proper nutrition, but she stated it is still unknown whether these interventions affect longer-term survival, though the QOL implications are clear. No specific guidelines exist for determining the level of fitness for candidates, but many options are available. Conrad noted that many providers monitor patients with gross motor exercise tests, along with other tools such as developmental milestones, a pediatric multidimensional fatigue scale, or functional status estimates through the Lansky performance scale.2 She presented data showing the functional status of surviving pediatric recipients at 1-, 2-, and 3-year follow-up visits from 2008 through 2017, as displayed in Figure 4-4. Conrad explained that by 3 years after transplantation, nearly 80 percent of recipients reported normal function, and another 10 percent were active but tired easily.

Conrad suggested pediatric lung transplant recipients would likely benefit from a directed treatment rehabilitation exercise program to achieve their best functionality and QOL. Given the limitations, she said, they focus on a better QOL rather than length of survival. Rehabilitation and physical therapy are important tools to help them achieve normal activities in their lives, including school, sports, and good physical, social, and mental health outcomes. Finally, she advocated for sharing and testing methodologies between transplant centers to better understand which interventions can best produce these outcomes to support their patients.

Heart Transplantation

Nine out of every 1,000 live births result in a child with congenital heart disease (CHD), stated Clifford Chin, director of Advanced Cardiomyopathy Services and medical director of Pediatric Heart Transplant at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (AHA, 2021). Chin went on to say that one-third of those will require surgery early in their lives. CHD is one of the major reasons a child might need a transplant, in addition to cardiomyopathy, a condition where the heart cannot pump enough blood needed for the body. Eventually, dilated cardiomyopathies overcome CHD as the leading indication for transplantation among adolescents. While neurological complications can be quite common, Chin said it is difficult to discern whether cognitive neurologic defects exist prior to cardiac

___________________

2 The Lansky performance scale measures QOL, including psychosocial and functional status, in children (Lansky et al., 1987).

SOURCES: Carol Conrad presentation, March 22, 2021; International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) International Thoracic Organ Transplant (TTX) Registry.

surgery in infants. Nonetheless, infant patients are at highest risk for severe developmental delay, which has consequences for future employability, insurability, educational achievement, and physical activity. Worldwide, Chin highlighted that approximately 25 percent of pediatric heart transplants each year occur in infants (Dipchand et al., 2013); children between the ages of 1 and 10 make up approximately 35 percent. Each year, the United States has roughly 500 heart transplants in children, defined as receiving a new heart prior to reaching their 18th birthday.

Chin described QOL assessment tools, including the Pediatric QOL Inventory tool (PedsQL), which assesses five domains of health: physical, emotional, psychosocial, social, and school functioning. The health-related QOL Inventory focuses more specifically on the effects of illness and the impact that treatment may have on QOL. Generally, children with more severe cardiovascular disease experience poorer physical and psychosocial QOL. Chin reported that even after transplantation, heart recipients have lower health-related QOL compared to children who are healthy, have chronic conditions, or have CHD. Going into transplant, children of different age categories will present differently but are generally very ill and may require life support. Chin stated that older children and adolescents who have had multiple surgeries typically do not require hospitalization while waiting for a heart but are often not well enough to attend school. Similarly,

cardiomyopathy patients considered for transplant are generally too fragile to attend school and are often hospitalized for months on intravenous medications. Some develop severe dysfunction of the heart, requiring mechanical support devices, which can lead to other health risks.

Describing what may happen after a heart transplant, Chin said that a clock begins that will count down until the patient passes away or requires a second transplant. Chin explained that the half-life3 for pediatric patients to arrive at this point is approximately 20 years but varies depending on the age at transplant (Rossano et al., 2019). Chin indicated that infants have better overall survival outcomes as compared to teenagers. He said that if 100 infants received a transplant today, one would expect 50 of them to be alive with their first transplanted heart in 25 years. On the other hand, if 100 teenagers were transplanted today, 50 of them would be alive in only 14 years. Chin added that because of improvements in half-life during the past two decades, cardiac retransplantation in pediatric patients is uncommon. For those that do require transplantation, the half-life of the second transplant is shorter; it may be only 10 years.

Chin described a number of clinical consequences pediatric patients may experience after heart transplantation. He said many patients develop kidney disease and described risk factors for the development of kidney disease this include preexisting disease, effects of surgery and hospitalization, use of anti-rejection medications, and age at transplant. While the majority of children do not experience severe kidney disease at 10 years after transplantation, Chin said that 10–15 percent of the population will require some form of dialysis by 20 years. He mentioned cancer is a problem that affects a small number of transplant patients and that most of the cancers that do develop are thought to be due to immunosuppressive medications in combination with certain viruses, especially Epstein-Barr virus infection, that can lead to the development of lymphoma. Chin also reported on repeated posttransplant hospitalizations, saying that although they do decrease over time, even 5 years after transplantation, 30 percent of patients are readmitted due largely to rejection and infection (Rossano et al., 2019). In terms of function, 70 percent of children report being fully active after 3 years, with the majority of the remainder having some limitations on strenuous activity (Rossano et al., 2019).

___________________

3 Half-life is the time required for a quantity to reduce to half of its initial value; in the context of transplantation, it refers to the time it takes for half of the grafts functioning at 1 year to subsequently fail.

Chin explained that it is possible to objectively measure exercise capacity and quantitate functional status. Compared to healthy children, pediatric transplant recipients have reduced exercise capacity, including lower peak oxygen consumption, higher resting heart rate, and lower peak heart rate. Cardiac rehabilitation programs and the significant benefits they can provide (increased in exercise capacity and muscle strength) are not widely available to children. Chin noted that compared to the 2,500 certified adult cardiac rehabilitation programs in the United States, there are just 10–15 certified pediatric programs. Currently, he said, pediatric heart transplant patients are set up to be deconditioned and less active, which leads to a weak foundation as they transition to adulthood.

Finally, cardiac transplantation is not a cure, Chin emphasized. While it is a lifesaving treatment, it creates a chronic health condition that depends on medications with adverse effects and limits to daily activities. Developmental delay and impaired cognitive function, the absence of pediatric resources to improve physical health, and inherent problems of transitioning from pediatric to adult programs are just a few of the barriers that hinder success for these patients.

ADOLESCENT TRANSITIONS TO ADULTHOOD AFTER TRANSPLANTATION

Transitioning to adult-oriented care is a challenging endeavor for many adolescent recipients. In Session 2, Nitika Gupta, professor of pediatrics at the Emory University School of Medicine, presented the current status of this transition, expanding on several points made earlier by Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris. Four million young adults in the United States turn 18 each year, with 18–20 percent of them affected by chronic health conditions (Goodman et al., 2011). This translates to around 750,000 patients with special needs transitioning from pediatric to adult health care every year, she said, and less than half receive adequate support and services (Goodman et al., 2011; McManus et al., 2013; Rosen et al., 2003). Evidence suggests this transition is associated with adverse health outcomes (Toomey et al., 2013). Gupta stated that, based on OPTN data, children make up approximately 2–13 percent of all transplants, depending on the organ type. While this is a small percentage compared to adults, children have a much longer lifespan ahead of them, resulting in many more years of managing their new organ.

While the morbidities and outcomes of pediatric transplants have been discussed for various organ types, Gupta focused on a general overview of

what happens when patients move from pediatric to adult health care. She shared a study examining liver transplant patients who survived about 20 and 25 years after transplantation. The main findings were that survival in children transplanted between ages 11–15 and 15–17 was worse than that of children who were transplanted before their 5th birthday (Ekong et al., 2019). Additionally, older age at transplant was associated with worse patient and graft survival. Gupta also highlighted a study from her center that found increased mortality in children who transferred from pediatric to adult care: one in four young adult liver transplant recipients died after that transition, and she noted that African Americans constituted the majority of these (Katz et al., 2021).

Factors Affecting Outcomes in Pediatric Transplant Recipients

Gupta asked what patient factors should be considered that may adversely affect these outcomes in pediatric transplant recipients. She highlighted the teenage brain, noting it is still very much under construction, with dissociated decision making and strong emotion, even in healthy children. The cerebral abilities that mature latest include foresight, planning, and risk/reward evaluation. Patients with chronic diseases may also have delayed maturation in psychosocial spheres and autonomy. She described the typical adolescent transplant patient: long-term survival is limited, substance abuse peaks, and the suicide rate is tripled. Gupta said that overall, the mortality rate of 18–24-year-olds is twice that of those 12–17, and up to one-third of adolescent transplant patients are nonadherent to medication regimens (Paraskeva et al., 2018). Several studies show risk factors for and causes of nonadherence, including the number of years after transplantation, sex, and parental stress and anxiety, but she noted a risk factor that has been apparent in several studies is a single-parent home, emphasizing the importance of social support (Berquist et al., 2006). Fredericks et al. (2007) showed that functional outcomes include evidence of poor cognitive, intellectual, and health-related QOL after transplantation.

Gupta was optimistic that knowledge of the developing adolescent brain can help providers and caregivers be empathetic and understanding regarding the needs of teenagers and young adults, and thus may facilitate implementation of interventions that support improved functioning in these patients. She highlighted transition programs that support adolescents as they transfer to the adult care setting and place emphasis on individual needs, customized care and treatment, and tracking outcomes. For example,

Gupta shared that her team developed the Adolescent Program 101,4 which takes a multidisciplinary approach involving providers, patient navigators, social workers, peer support, telemedicine, and other initiatives—and provides intensive monitoring and education as patients transfer to the adult setting.

DISCUSSION

Dorry Segev, associate vice chair of the Department of Surgery at JHU, moderated Session 2. He began by asking the panelists what might contribute to the differences between adult and pediatric survival rates among the various end-organ groups and why some organs show much better pediatric survival when others may even be worse than adult rates. Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris responded in the context of kidney transplant patients, saying that 10-year posttransplant survival is actually greater for children than adults, but the reason is not completely clear. Some theories include the fewer comorbidities in adolescents and young adults, such as heart disease, diabetes, or lung disease. She also highlighted a study looking at approximately 168,000 transplants across the country up to 55 years old and found that the 14–16-year-old age group—especially those with public insurance and minority status—are at the highest risk of losing their transplanted organ (Andreoni et al., 2013). Gupta agreed, noting similar findings have been seen in liver recipients. She described a study of 25-year outcomes, in which 14–17-year-olds were also the highest risk group (Ekong et al., 2019). Gupta again called attention to the developing adolescent brain and the need for more empathy and support.

Lung transplantation may be unique, said Conrad, because the organ is constantly exposed to the environment, whereas the other organs are generally protected. One concern is that teens join their peer groups and want to do the things they are doing, which can include inhaling substances—even passively. This has especially been more of an issue with the increasing rate of marijuana legalization around the country, Conrad said. Aside from CF patients, she said typically the worse survival rates are not related to recurrence of baseline disease, but she also acknowledged they still do not understand why lungs fibrose. For heart transplants, Chin said adolescent half-lives were quite similar to adults, around 14–15 years, compared to

___________________

4 See http://prd-choa.choa.org/medical-services/transplants/adolescent-and-young-adult-program (accessed May 24, 2021).

babies, who have much higher half-lives (25 years). He attributed this to babies being immunologically naïve, compared to older children or adults who are immunologically mature. But he also pointed out that if patients are transplanted as babies, they grew up with posttransplant life as their normal life and are accustomed to all the things that go with it. Chin compared this to a cardiomyopathy patient who may have led a normal life until 16 or 17 and then suddenly becomes sick with numerous new restrictions and obligations; such a patient is more likely to resist recommended treatment regimens, Chin said.

Nonadherence in Children and Adolescents

Segev recalled a study that found that those who had a functioning allograft at age 17 had a 42 percent chance of losing it by the time they were 24 years old (Van Arendonk et al., 2013). During this high-risk window, nearly half of kidney allografts are lost, he said. He asked how the effect of nonadherence with transplant follow-up procedures can be quantified. Segev also asked whether it was possible to quantify the effect on survival rates if nonadherence could be reduced or eliminated. Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris noted the lack of strong agreement on the definition of nonadherence, so it is difficult to quantify. Another challenge is that patients want to live a normal life, but living with chronic disease is difficult and can be a vicious cycle. For example, in CKD, 30–40 percent of adolescents have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. They do not perform well in school, do not have great job outlooks, and can have anxiety and depression, as well as high-risk behaviors, which can lead to a vicious cycle that results in nonadherence. They also have employment issues, with nearly half living with their parents, so the experience of growing up and transitioning to adulthood is not the same compared to typical adolescents. Gupta again emphasized the point about single-parent homes contributing to nonadherence, but as children become older, the need for oversight lessens. Additionally, she pointed out a need to reflect racial disparities, and also immune systems differences, when considering nonadherence. Chin added that it is very difficult to quantitate, but there are some possible approaches for detecting nonadherence. For example, drug screenings may be able to help determine whether a patient is following recommended medication regimens.

ASSESSING PHYSICAL, COGNITIVE, AND PSYCHOSOCIAL FUNCTION AFTER ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION IN CHILDREN

As many speakers noted, children face unique challenges as they adjust to their lives following transplantation. In Session 5B regarding physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning following transplantation in children, speakers described methods of assessing patient functioning and presented research findings on short- and long-term effects of transplantation on functioning and QOL. A panel discussion further explored the topic of impairments following an organ transplant that can lead to disability in children.

Physical and Cognitive Functioning

Compared to adults, children are transplanted early in life and may have other congenital diseases that cause impairment, but they tend to be quite resilient, said Saeed Mohammad, medical director of pediatric hepatology and liver transplantation at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. A critical time of development is affected by transplantation and use of immunosuppressive medications from childhood for many years can also affect the developing brain. Defining functioning can include physical and cognitive realms, where age and pretransplant health status are also important determinants. Functional assessment measures that are age appropriate may be more difficult for children who are chronically ill, because they usually have not attained the milestones expected for certain ages. Ratings may be done by self or proxy (such as a parent), but proxy raters often report more impaired functioning than standardized tests, which tend to underestimate the abilities of children with chronic illnesses, Mohammad explained.

Physical functioning is typically measured through observation of physical ability, such as attaining milestones, the 6-minute walk test, or the Lansky performance scale. Cognitive functioning tools depend on a child’s development but could include IQ tests or specific tests of executive functioning and visuospatial abilities. Survey instruments, such as PedsQL or the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System scale, could be used for either physical or cognitive functioning. Mohammad presented data on kidney recipients transplanted before the age of 5. Poor developmental outcomes were associated with long-term dialysis, and with

hemodialysis (Popel et al., 2019). Kidney transplant recipients had lower visual-motor integration, full-scale IQ, and general adaptive composite scores. A separate study of heart transplant patients compared those with CHD to those who had a failing heart. Despite all of them having been transplant recipients at a very young age, the patients with CHD scored lower (Urschel et al., 2018). He highlighted the differences between the two groups, noting that those with CHD have more surgeries, greater kidney injury, and more days in the ICU, demonstrating the significance of the course of illness before transplantation in addition to other factors.

Liver recipients also had cognitive functioning studied. Mohammad shared one study of a multicenter trial across three time points that showed both cognitive functioning and school functioning decreased over time. The study suggested that more than half of the adolescents with liver transplants may be at risk of poor school functioning (Ohnemus et al., 2020). Mohammad said this could also be because as patients transition into high school, they may have difficulty adjusting to the increased demands on their brains’ executive functioning.

When discussing areas for improvement, Mohammad noted that physical functioning in children is closest to normal in liver and kidney recipients, but heart recipients are the most at risk for functional deficits. Pediatric heart patients are generally transplanted at a young age and are very ill before transplantation. They also typically have lower oxygen levels, which may affect their cognitive outcomes. Cognitive functioning may also worsen with age due to the increased need for executive functioning. Regarding knowledge gaps and possible interventions for improving functional outcomes, he identified a need for functional assessment measures collected in real time to enhance the identification of modifiable factors. Mohammad explained that existing measures identify a problem but cannot indicate when it occurred (before transplantation or around the time of surgery), making it difficult to know how best to intervene to improve outcomes. Real-time assessment measures might help overcome this barrier, he said.

Psychosocial Risk Factors Associated with Transplant Outcomes in Children

Eyal Shemesh, chief of the Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics at Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital, emphasized that children are not just small adults. They have different trajectories and

somewhat different risks following transplantation. Pediatric transplantation is best viewed as a lifesaving transition from a deadly risk to a chronic illness, he said, echoing previous comments, but it is not a cure that brings children to full health. Transplantation means a lifelong commitment to immunosuppression management. While the outcome is often a long and productive life, Shemesh said transplantation can lead to many complications and this is especially true with children who may live with a transplant the majority of their lives.

Emphasizing that that cognitive impairment is an important concern in children, Shemesh said that a large percentage of pediatric transplant patients have schooling difficulties. Based on his research—mainly on a liver transplant prospective child cohort assessed 1 year after transplant—Shemesh indicated that psychosocial demographic challenges were top predictors of risk. He shared the following predictors of cognitive impairment, cautioning that they are not necessarily causal but only indicate a risk:

- History of child abuse

- Single-parent household

- Zip code (often a proxy for low socioeconomic status)

- Race (African American)

- Sex (female, especially predictive in adolescent populations)

Monitoring is very important, continued Shemesh, including adherence to medical recommendations, which is something that is unique to transplant patients. Transplant patients must take immunosuppressive medications consistently for the rest of their lives. Monitoring school functioning is also important, given the cognitive impairment risks. Shemesh shared data from a liver transplant child cohort study showing that in adolescents, 53 percent who were nonadherent had a rejection episode, compared to just 6 percent of those who were adherent (Shemesh et al., 2017). He said awareness of the risk of nonadherence is a step toward mitigating it. Because children can change as they grow and develop, assessments and evaluations need to be repeated again and again, especially during adolescence, so the level of risk can be proactively addressed. Shemesh stressed that in the young transplant population, all family members need support, not just the patient. He added that resources for additional support should be allocated for patients who are at high risk, with special attention to the prevalence of PTSD and depression.

DISCUSSION

Lease and Rogal co-moderated the discussion. Lease first asked Mohammad how effective cognitive interventions are at improving cognitive function in children and how it might vary based on the underlying causes of the decline. He replied that in general, most kids are transplanted quite early, before they turn 5, so there is not a lot of testing before transplantation. It can also be difficult to differentiate complications that happen after transplantation from something that was part of the underlying disease. He referred to the example of recipients with CHD having worse cognitive outcomes compared to those with other types of heart disease, and he said they see the same thing in liver recipients. Patients with metabolic diseases that can affect the whole body struggle more than those with other liver ailments.

Turning to Shemesh, Lease wondered how long after transplantation would anyone be able to generally see the apex of functioning in children. Shemesh responded he did not think of functioning as a linear trajectory. He envisions function as a “seesaw” or something that is coming and going, which is why it is most important to monitor progress or decline. In addition to the risk period of adolescence, he said, studies of long-term trajectory show a risk period in adulthood.

Regarding what might be specifically beneficial for children, Mohammad cited a need for resources to monitor their physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development, but said such resources are not always easily available. For example, clinicians may refer a child who is struggling to a therapist or psychologist, but it is often up to the family to find someone, which can be very difficult. That provider also may not be well versed in the specific challenges transplant recipients face, which might include PTSD from hospitalization, difficulty adhering to medication regimens, or the vulnerability that may come from being different from other children. This is definitely an area that could benefit from more easily accessible resources, he stated. Shemesh added that children are naturally completely dependent on their parents, but in cases where the parent is not completely functional, then it may necessary to create an environment around the child that can help them thrive, regardless of their situation.

In terms of monitoring those who are not able to access regular health care, Shemesh said the COVID-19 era catapulted them into remote monitoring more quickly than he could have imagined. He is working on research to show the efficacy of these remote appointments, which would

inherently remove the burden of traveling to the clinic. He also described multiple apps that try to interact with patients to have them check in with their care team and communicate directly with the care team if something is going wrong or they have questions.

One thing about adult transplantation programs, said Lease, is that they do not have the same structure or resources built into them as the pediatric programs do. She asked for suggestions for adult transplantation programs that are now taking care of pediatric patients who have transitioned into their care. Shemesh said it may help if programs focus on not only the adult side but also the pediatric side. As young patients approach a transition to adult care, he suggested a separate transition program may ensure pediatric patients are ready for the next stage of care by helping them to build self-sufficiency. Mohammad added that the volume of pediatric patients is smaller compared to adults, so it is difficult for adult programs to mimic everything that is done. Lease noted that adolescence is very vulnerable, and she cautioned against losing the opportunity for them to maintain their progress.

Rogal commented on the fine line between monitoring adherence and blaming the patients, as adherence is not merely related to motivation and may be influenced by systemic barriers. Shemesh agreed, saying he had studied adherence in both adults and children, but children may have a better chance to benefit from adherence interventions because they often have a parent or other partner that can be involved. He advocated for specifically targeting resources instead of trying to make sure that everyone in the clinic gets everything available, because some patients will have much more of a need. The resources could include social workers, psychologists, or physicians, but it depends on the case. Shemesh noted that the largest predictor of nonadherence in their cohort was child abuse, a horrific intersection with transplantation (Shemesh et al., 2007). Mohammad added that tailoring the services to the population is necessary, agreeing that some patients need more help and reminders to adhere to the treatment schedules. He also highlighted the importance of understanding family situations, using the example of housing instability. If medications need to be refrigerated but patients cannot consistently comply, they are not able to take the medications as prescribed. Understanding each family’s position as to why this happens is important, he said, and so is the need to be sensitive to the stigma associated with things such as being unable to afford medications.

Lease asked if there were special SSA considerations when the child is receiving disability benefits and is in the child welfare system. Shemesh

acknowledged he did not know SSA considerations specifically but argued that those children who are in the transplant system need more resources to support their health and QOL. Mohammad agreed they are a higher-risk population and could be monitored more closely and provided with more resources earlier after transplantation.

A final question was about posttransplant functioning after adolescence, based on the level of adherence during adolescence, for those patients who survive into young adulthood. Shemesh noted the selection bias, because the only outcomes to examine would be in patients who did survive that tumultuous period. In addition, he said there is some indication in the literature that if patients make it through the vulnerable period of adolescence, they can improve afterward. But, Shemesh added, many patients do not make it through a period of adolescent nonadherence. Mohammad said for survivors, there may be no long-term effects on functioning, though they may lose a grade in school depending on how long they are hospitalized. But others may end up with diminished graft function, so the effects on functioning would be related to the number of medications and which side effects might be playing a role. Mohammad said that overall outcomes for pediatric patients are very good for liver, kidney, and heart transplants. They likely need close monitoring, and some will require more support, but he believed it is something that can be overcome for them to live a fairly normal life. Shemesh agreed, adding that the focus on the family unit when considering needs and outcomes for children is incredibly important, as any child will not do well when a parent is not well.