This chapter considers the knowledge and competencies needed by adults to more seamlessly support the health, learning, development, and school success of children from birth through age 8 by providing consistent, high-quality care and education. For its articulation of these competencies, the committee draws on the science of child development and early learning, the knowledge base about educational practices, and the landscape of care and education and related sectors. The chapter first summarizes foundational knowledge, skills, and abilities, or competencies, needed by adults who have professional responsibilities for young children. This is followed by a discussion of specialized competencies needed for quality practice for the care and education workforce, including the extent to which current statements of professional standards encompass these competencies. The final two sections examine knowledge and competencies for leaders and administrators, and for collaborative and coordinated practice among professionals within and across the closely related sectors of care and education, health, and social services.

FOUNDATIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND COMPETENCIES

The committee identifies the general knowledge and competencies in Box 7-1 as an important foundation for all adults with professional responsibilities for young children, across settings and sectors.

BOX 7-1

Foundational Knowledge and Competencies for All Adults with Professional Responsibilities for Young Children

All adults with professional responsibilities for young children need to know about

- How a child develops and learns, including cognitive development, specific content knowledge and skills, general learning competencies, socioemotional development, and physical development and health.

- The importance of consistent, stable, nurturing, and protective relationships that support development and learning across domains and enable children to fully engage in learning opportunities.

- Biological and environmental factors that can contribute positively to or interfere with development, behavior, and learning (for example, positive and ameliorative effects of nurturing and responsive relationships, negative effects of chronic stress and exposure to trauma and adverse events, positive adaptations to environmental exposures).

All adults with professional responsibilities for young children need to use this knowledge and develop the skills to

- Engage effectively in quality interactions with children that foster healthy child development and learning in routine everyday interactions, in specific learning activities, and in educational and other professional settings in a manner appropriate to the child’s developmental level.

- Promote positive social development and behaviors and mitigate challenging behaviors.

- Recognize signs that children may need to be assessed and referred for specialized services (for example, for developmental delays, mental health concerns, social support needs, or abuse and neglect); and be aware of how to access the information, resources, and support for such specialized help when needed.

- Make informed decisions about whether and how to use different kinds of technologies as tools to promote children’s learning.

SPECIALIZED KNOWLEDGE AND COMPETENCIES FOR EDUCATORS

This section considers what educators and education leaders who work with children from birth through age 8 need to know and be able to do to support important domains of development and learning and to support greater continuity for children along the birth through age 8 continuum. The discussion begins with a summary of what the committee has identi-

fied as the shared core knowledge and competencies needed by educators, or those professionals who provide direct, regular care and education for young children from birth through age 8, who may work with these children in home- or center-based childcare settings, early childhood education centers and preschools, and elementary schools. This is followed by an overview of the extent to which current statements of core competencies at the national and state levels encompass the identified knowledge and competencies. Knowledge and competencies for leadership in care and education are discussed later in the chapter, as well as competencies for collaboration and communication among different professional roles, referred to in this report as interprofessional practice.

As described in Chapter 1, the committee’s focus was identifying the competencies that, to support greater consistency in high-quality learning experiences for children, need to be shared in common for educators across the birth through age 8 continuum and across professional roles and practice settings, as stated in the statement of task. This includes areas in which these care and education professionals will benefit from understanding the scope of learning—and the scope of educational practices—for the settings and ages that precede or follow them within the birth through 8 age range. Further specialized competencies and professional learning differentiated by age, setting, and/or role are important, but this study avoids duplicating or supplanting existing infrastructure or processes for articulating, reviewing, and guiding them. Rather, this committee’s charge was to bridge those efforts and assist each of them in refining their efforts to collectively and more effectively contribute to greater consistency and continuity for children.

Finally, while this section and this chapter cover knowledge and competencies at the individual level, it is important to note that a focus on the individual is not sufficient, and professionals cannot be expected to bear the responsibility for quality practice alone. Part IV covers professional learning systems with responsibility for supporting and continuously updating the acquisition and application of these knowledge and competencies. Even beyond professional learning systems, however, adults who have mastery of the necessary knowledge and competencies may still be constrained in putting them into practice by the circumstances and work environments of the settings and systems in which they practice and by the policies that support those settings and systems, as previously described in Chapter 2. Therefore, Part IV also examines characteristics of settings and systems that are needed to ensure quality and to support individual practitioners.

Core Competencies for Educators

In addition to the foundational knowledge and competencies described in the preceding section, the committee identifies in Box 7-2 the knowledge

BOX 7-2

Knowledge and Competencies for Care and Education Practitioners

Core Knowledge Base

- Knowledge of the developmental science that underlies important domains of early learning and child development, including cognitive development, specific content knowledge and skills, general learning competencies, socioemotional development, and physical development and health.

- Knowledge of how these domains interact to facilitate learning and development.

- Knowledge of content and concepts that are important in early learning of major subject-matter areas, including language and literacy, mathematics, science, technology, engineering, arts, and social studies.

- Knowledge of the learning trajectories (goals, developmental progressions, and instructional tasks and strategies) of how children learn and become proficient in each of the domains and specific subject-matter areas.

- Knowledge of the science that elucidates the interactions among biological and environmental factors that influence children’s development and learning, including the positive effects of consistent, nurturing interactions that facilitate development and learning, as well as the negative effects of chronic stress and exposure to trauma and adversity that can impede development and learning.

- Knowledge of principles for assessing children that are developmentally appropriate; culturally sensitive; and relevant, reliable, and valid across a variety of populations, domains, and assessment purposes.

Practices to Help Children Learn

- Ability to establish relationships and interactions with children that are nurturing and use positive language.

- Ability to create and manage effective learning environments (physical space, materials, activities, classroom management).

- Ability to consistently deploy productive routines, maintain a schedule, and make transitions brief and productive, all to increase predictability and learning opportunities and to maintain a sense of emotional calm in the learning environment.

- Ability to use a repertory of instructional and caregiving practices and strategies, including implementing validated curricula, that engage children through nurturing, responsive interactions and facilitate learning and development in all domains in ways that are appropriate for their stage of development.

- Ability to set appropriate individualized goals and objectives to advance young children’s development and learning.

- Ability to use learning trajectories: a deep understanding of the content; knowledge of the way children think and learn about the content; and the ability to design and employ instructional tasks, curricula, and activities that effectively promote learning and development within and across domains and subject-matter areas.

- Ability to select, employ, and interpret a portfolio of both informal and formal assessment tools and strategies; to use the results to understand individual children’s developmental progression and determine whether needs are being met; and to use this information to individualize, adapt, and improve instructional practices.

- Ability to integrate and leverage different kinds of technologies in curricula and instructional practice to promote children’s learning.

- Ability to promote positive social development and self-regulation while mitigating challenging behaviors in ways that reflect an understanding of the multiple biological and environmental factors that affect behavior.

- Ability to recognize the effects of factors from outside the practice setting (e.g., poverty, trauma, parental depression, experience of violence in the home or community) that affect children’s learning and development, and to adjust practice to help children experiencing those effects.

Working with Diverse Populations of Children

- Ability to advance the learning and development of children from backgrounds that are diverse in family structure, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, culture, and language.

- Ability to advance the learning and development of children who are dual language learners.

- Ability to advance the development and learning of children who have specialized developmental or learning needs, such as children with disabilities or learning delays, children experiencing chronic stress/adversity, and children who are gifted and talented. All early care and education professionals—not just those in specialized roles—need knowledge and basic competencies for working with these children.

Developing and Using Partnerships

- Ability to communicate and connect with families in a mutually respectful, reciprocal way, and to set goals with families and prepare them to engage in complementary behaviors and activities that enhance development and early learning.

- Ability to recognize when behaviors and academic challenges may be a sign of an underlying need for referral for more comprehensive assessment, diagnosis, and support (e.g., mental health consultation, social services, family support services).

- Knowledge of professional roles and available services within care and education and in closely related sectors such as health and social services.

- Ability to access and effectively use available referral and resource systems.

- Ability to collaborate and communicate with professionals in other roles, disciplines, and sectors to facilitate mutual understanding and collective contributions to improving outcomes for children.

Continuously Improving the Quality of Practice

- Ability and motivation to access and engage in available professional learning resources to keep current with the science of development and early learning and with research on instructional and other practices.

- Knowledge and abilities for self-care to manage their own physical and mental health, including the effects of their own exposure to adversity and stress.

and competencies that are important for all professionals who provide direct, regular care and education for young children to support development, foster early learning, and contribute to greater consistency along the birth through age 8 continuum.

Current Statements of Professional Standards and Core Competencies for Educators

One of the factors that contributes to continuity in high-quality learning experiences is continuity in the stated expectations for the care and education professionals who work with children throughout the age 0-8 continuum. This section describes the extent to which the knowledge and competencies identified in the preceding sections are reflected in current statements of professional standards and core competencies, focusing on the role of educators. This is followed by a discussion of how stated core competencies could be improved to better reflect both the science of child development and the science of instruction, as well as to reflect more aligned expectations for care and education professionals across roles and settings.

Comparison of National Statements

A scan of the stated professional standards or core competencies from four national organizations provides a sense of the expectations that have been articulated for care and education professionals who work with children through age 8:

- The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) has developed “Standards for Early Childhood Professional Preparation” (NAEYC, 2009).

- The National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) has a set of “Early Childhood Generalist Standards” that apply to teachers of children from ages 3 to 8 (NBPTS, 2012).

- The Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (InTASC) of the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) offers “Model Core Teaching Standards” for K-12 teachers (CCSSO, 2011).

- The Division for Early Childhood (DEC) of the Council for Exceptional Children has issued “Recommended Practices in in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education” (DEC, 2014).

These statements from national organizations are consistent in saying that effective educators need to possess the following knowledge and competencies, which also are consistent with those identified by this committee:

- working effectively and equitably with children from diverse backgrounds—cultural, socioeconomic, and linguistic—and of different ability levels;

- creating and using supportive learning environments, including physical space, materials, and activities;

- having the capacity (knowledge and skills) to support children’s learning and development across multiple domains, including cognition, language and literacy, socioemotional skills, learning competencies, executive function, physical health, and moral and ethical development;

- understanding core concepts of major content areas and having the ability to use that knowledge to design curricula and activities that help children understand and apply these concepts;1

- knowing how to assess children appropriately and using assessment results to inform practice;

- setting appropriate goals and objectives for learners based on understanding of the children’s development across domains and content knowledge, and planning, designing, and selecting instructional activities and approaches accordingly;

- using a repertoire of strategies that engage children across content areas and domains in developmentally appropriate ways while making ongoing adjustments based on children’s progress to foster further growth;

- engaging in professional learning opportunities to improve practice and in leadership opportunities to advance the field;

- collaborating with other early care and education professionals and those from related fields to support children holistically; and

- partnering with family members to support children’s learning and development.

Given the commonly cited differences in philosophies, policies, and approaches between the early childhood (birth to age 5) and elementary education communities, some of the above similarities are worth highlighting. First, there is an assumption that elementary education systems neglect children’s development in areas other than the academic, and that “standards-based” reform is “pushing” expectations and teaching strategies down the age continuum from the older grades and encouraging practices that are inappropriate for children in prekindergarten through third grade. Setting aside whether that is indeed the case, it is interesting that all of the above national statements expect professionals—whether they are working with the youngest children or third graders—to know how to support

_____________

1 The InTASC standards do not name specific content areas.

children’s development across domains, in general cognitive skills, specific academic skills, learning competencies, socioemotional development, and health and physical well-being. All four statements of competencies also expect professionals to work with children in developmentally appropriate ways and to collaborate with colleagues in early care and education and in other related fields if necessary to support children’s learning and development comprehensively.

Similarly, a common perception about early childhood professionals (those who work with children under the age of 5) is that they lack adequate understanding of early learning in content areas or focus more on how children are developing in the socioemotional domain and in general learning competencies than on the foundations of learning discrete subjects. Yet both the NAEYC and the NBPTS standards express explicit expectations that these professionals understand content knowledge in specific subject areas and have the ability to use that understanding to develop curricula, learning environments, and learning activities.

While these four statements suggest significant agreement as to what early care and education providers for children under age 5 and early elementary grade educators should know and be able to do, some nuances and variations exist in a number of areas:

- Assessment—The NAEYC and DEC standards place more emphasis on professionals’ proficiency in using observational assessments, systematic and everyday documentation of children’s progress, and screening tools. The InTASC standards emphasize using multiple assessment strategies and distinguishing between formative and summative assessments—concepts that are not mentioned in the NAEYC statement. The NBPTS standards address the need to differentiate between formative and summative assessments, but also the value of observations and performance-based assessment that yield anecdotal evidence and work samples that can be meaningful. Both InTASC and the NBPTS, however, are largely silent on knowledge of and the ability to use screening tools. The InTASC standards also do not focus on professionals’ ability to communicate assessment results to family members and other colleagues—skills that are included in the NAEYC, DEC, and the NBPTS standards.

- Family engagement—While all four sets of standards speak to skills related to engaging families, the InTASC standards tend to emphasize these skills as means to support children’s learning and development. The NAEYC, DEC, and the NBPTS also discuss this purpose of partnering with families, but they also expect professionals to have competencies related to helping families access other services that support their children’s well-being.

- Technology—The NAEYC’s position statement on technology provides guidance on developmentally appropriate practices for educators with respect to interactive media and technology, though it does not identify required competencies. Technology is identified as an important influence on children’s learning and development, and while there are no NAEYC standards specific to technology, it is integrated as a component of the NAEYC standards. The recognition of technology is limited to its use as a method of communication between educators and families, as well as a source of tools for child assessment and professional learning (NAEYC, 2009). Conversely, the NBPTS standards include technology as a subject matter and state that educators should support young children in using technology as a tool. The NBPTS further articulates that accomplished educators are knowledgeable about technology and aware of new technological advances, and understand how children use technology to nurture their curiosity and learning (NBPTS, 2012). Similarly, InTASC identifies technology as a theme that cuts across many standards related to learning environment, content, application, and assessment; planning; instructional strategies; professional learning; and leadership (CCSSO, 2011). InTASC’s definition of learning environment includes the use of technology, which can allow children to work and engage with collaborators outside the classroom, as well as personalize their own learning. Standards require educators to teach and promote responsible and safe use of technology in order to achieve specific learning goals, help build children’s capacity for working productively and collaboratively, and understand the demands and challenges of using technology (CCSSO, 2011).

Comparison of National and State Statements

Many states also have developed formal core competencies for early care and education professionals.2 Most of them focus on professionals who work with children below the age of 5, although many also include those who work with K-3 and in a few cases even older students as well. Some states have different sets of competencies for more specialized roles, such as home visitors or early interventionists, and for different settings, such as home-based or center-based care. This discussion focuses on competency statements for educators.

_____________

2 A scan was conducted of a sample of states to compare examples of core competencies statements for care and education professionals in the birth through age 8 continuum across states and between state and national statements.

In general, states’ expectations for early care and education professionals align with those articulated in national statements, especially that of the NAEYC. Importantly, state and national statements of core competencies reflect the notion that “education” goes beyond academic success to encompass other domains, such as socioemotional development and physical and mental health, that also contribute in important ways to students’ success in school and in life. Thus, statements for both educators who work with young children and those who work with early elementary students uphold the importance of addressing all of the domains of development and learning, not just academic skills. These statements also expect professionals to learn how to collaborate with each other and colleagues from other fields so that if necessary, children have access to other services that contribute to their well-being and academic success.

For states that have articulated core competencies specifically for those who work with infants and toddlers;3 these statements tend to elevate the importance of being effective in partnering with and supporting family members and include more specialized skills for this, such as “family-centered practices” that include joint decision making between family members and practitioners (Ohio Child Care Resource & Referral Association, 2008); skills related to applying theories of attachment and separation in practice and integrating families into the process of identifying and addressing children’s special needs through early intervention (New York State Association for the Education of Young Children, 2009); and understanding the family’s beliefs and values related to child-rearing, communicating with the family about children’s growth and development, collaborating with parents throughout the assessment process, and integrating families’ goals and culture into curricula and learning environments (New Hampshire Department for Health and Human Services and Child Development Bureau, 2013).

Despite this broad agreement between the core competencies identified by states and national organizations, some significant differences exist. First, the core competencies of states tend to place more emphasis on skills

_____________

3 Only three states have separate documents outlining specific competencies for professionals who work with infants and toddlers. Those states are Maine (http://muskie.usm.maine.edu/maineroads/pdfs/ITC1_Cred_Guide_Manual.pdf, accessed March 25, 2015), New Hampshire (http://www.dhhs.state.nh.us/dcyf/cdb/documents/infant-toddler-competencies.pdf, accessed March 25, 2015), and New York (http://nysaeyc.org/wp-content/uploads/ITCECCompetencies.pdf, accessed March 25, 2015). Two states have published documents for these professionals that are used to augment generalized early childhood competencies: Minnesota (Companion document) (http://www.cehd.umn.edu/ceed/projects/ittcguide/default.html, accessed March 25, 2015) and Ohio (standards including infant and toddler caregiver competencies) (http://occrra.org/it/documents/ITStandards.pdf, accessed March 25, 2015). Personal communication, B. Gebherd, ZERO TO THREE, 2014.

related to promoting health, safety, and nutrition, often calling them out as separate competency areas. Second, states also tend to include competencies related to the business of operating or managing an early learning program, such as relevant legal issues, financial planning, and human resources. Third, instead of calling out content knowledge as a competency area, as the national statements do, early care and education competencies from states embed it in other competencies, such as “teaching practices” or “learning environment and curriculum.” Most of these statements do differentiate professionals’ competencies in instruction, building a curriculum, and creating a learning environment for different content areas, which often include mathematics, language and literacy, science, social studies, art, and sometimes technology. In some cases, though, the concept of content knowledge appears to be broadly defined as language and literacy and part of cognitive development.

Opportunities for Statements of Educator Core Competencies to Better Reflect the Science

The above scan of both national and state statements of core competencies suggests that there is broad agreement on what educators who work with children from infancy through age 8 need to know and be able to do. The existence of core competencies for professionals in early childhood settings represents an effort to bring coherence to a workforce with highly diverse expectations and backgrounds, and the general agreement among the competencies is an indication of some emerging alignment. Despite this broad agreement, however, there are also some variations in emphasis in a few areas. As described previously, the early childhood and elementary education fields vary somewhat in their statements of what educators’ competencies should be in the areas of assessment and family engagement, and reconciling these differences could be constructive for educators, children, and families.

At the same time, the science of how children develop and learn (as described in Part II) and the important role of high-quality educational practice in fostering developmental progress for children (as described in Chapter 6) point to a number of areas in which both national and state statements of core competencies could be improved. These areas are also emphasized in the competencies identified by this committee (see Box 7-2).

Teaching subject-matter–specific content Just having knowledge about various content areas and the major stages or milestones experienced by children is inadequate. As discussed in Chapter 6, effective instruction in subject areas (such as reading and math) results from a combination of knowledge of the subject; of the learning trajectories necessary for children

to gain proficiency in the subject’s major concepts, themes, and topics; and of developmentally appropriate pedagogy and content knowledge for teaching, that is, how to represent and convey specific content and how to design learning experiences to support children’s progression along the learning trajectories in the subject. Each subject area calls for a distinctive body of knowledge and set of competencies. In short, having content knowledge and knowing the major developmental milestones in any given subject area does no good if the educator does not know how to link that knowledge to instructional practices and engineer the learning environment to support children’s growth in that subject.

Among states’ statements of core competencies for early childhood educators, New Mexico’s comes close to this concept. It calls for early learning professionals to be able to “use their child development knowledge, their knowledge of developmentally appropriate practices, and their content knowledge to design, implement, and evaluate experiences that promote optimal development and learning” for all children from birth through age 8. For example, to support the development of emergent literacy skills in young children, educators should be able to describe and implement developmentally appropriate strategies based on the stages of reading and writing across the developmental continuum, and identify ways to effectively implement these strategies (New Mexico Early Childhood Higher Education Task Force, 2011). Among the national statements, the NBPTS’s standards for early childhood generalists go into greater detail than others about the concepts for each subject area—language and literacy, mathematics, science, social studies, visual arts, music and drama, health education, physical education, and technology—and the skills professionals need to support children’s development in each.

Seen in this light, discussions of content knowledge in most existing statements of core competencies—whether at the state or national level—lack specificity (e.g., major concepts and themes in a content area are rarely included), or differentiation (e.g., embedding math and science under “cognitive development”), or both. Most existing core competencies for educators of young children are lacking in the area of describing developmentally appropriate practice for teaching specific content areas.

Addressing stress and adversity Educators of young children need to understand recent research on the interplay among chronic adverse experiences (e.g., poverty, trauma, stress); brain development; and children’s capacity to learn, exert self-control, and develop positive relationships (as discussed in Chapter 4). For example, Vermont’s core competencies for early childhood professionals expect beginning practitioners to understand that stress from adverse childhood experiences (e.g., trauma, abuse, neglect, poverty) affects child development and behavior and to be able to identify strategies that

can help recognize this stress. More experienced professionals are expected to consider the origins and effects of stress when working with children as well as the available ways to address their needs (Vermont Northern Lights Career Development Center, 2013).

Most existing statements of core competencies do emphasize the importance of working effectively with children with different learning needs and from diverse cultural, socioeconomic, and linguistic backgrounds, but nonetheless may not adequately address the competencies needed for early care and education professionals to work with children experiencing chronic stress and adversity. Competency statements could be improved by articulating what knowledge and skills early care and education professionals need to recognize learning challenges that result from stress and adversity, to adapt instructional practices that take these issues into account, and to implement what are sometimes referred to as “trauma-informed” practices that help children manage their emotions and behaviors while engaged in learning activities. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network has developed 12 core concepts that provide a rationale for trauma-informed assessment and intervention (NCTSN Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force, 2012), covering considerations for how to assess, understand, and assist children, families, and communities who have experienced trauma.

Fostering socioemotional development and general learning competencies According to national and state statements of core competencies, educators are expected to understand socioemotional development as well as how children develop general learning competencies, and to be able to create learning environments and experiences that support development in both of these major areas. However, most of the existing competencies related to these two domains tend to treat them monolithically or define them through a list of examples of skills that differ somewhat from document to document. In other words, most statements of competencies related to these domains do not appear to be grounded in a strong conceptual framework that identifies and differentiates major areas of development that care and education professionals should understand in addition to understanding relationships among the domains.

As discussed in Chapter 4, a growing body of research is focused on the important role of the development of executive function and self-regulation not just during the early childhood and early elementary years but throughout a student’s academic career and indeed, into adulthood. National organizations and states may also need to catch up with this research and articulate what educators of young children need to know about how generalized self-regulatory capacities regarding emotion, behavior, attention, and focus are linked to each other and to academic achievement and how

to design learning environments and engage specific teaching strategies to create experiences that cultivate these skills in children in developmentally appropriate ways.

Statements of core competencies tend not to specify what educators should know about how children’s socioemotional development and acquisition of learning competencies progresses as they grow from infants to toddlers to preschoolers to older students. As a result, most competency statements, especially those of states, only articulate generally what educators need to know to promote development in these areas; they do not address practices and strategies that they can design in these areas that are appropriate and specific for different age groups or for the distinct domains of socioemotional development and the growth of learning competencies. These domains of development are included in most national and state early learning standards for children, revealing a gap between what is expected for children and the specific competencies needed for educators to foster those learning outcomes.

Working with dual language learners Research on young dual language learners suggests that working effectively with these children requires both fundamental understanding of child development and learning and more specialized knowledge about how these children develop in various domains, how they respond to instruction, and what evidence-based practices have demonstrated success with this population. Yet while many statements of core competencies speak to the general need to respect cultural and linguistic diversity, they do not discuss in depth the knowledge professionals need of how these children learn, including the distinctive knowledge and capabilities required to support English acquisition and children’s home language development. Given that dual language learners are one of the fastest-growing populations in the nation, better articulation of these competencies is needed. California’s core competencies statement, for example, includes one of the most comprehensive discussions of this topic (California Department of Education and First 5 California, 2011). In addition, the Alliance for a Better Community (2012) recently developed “Dual Language Learner Teacher Competencies” that articulate what early childhood teachers should know and be able to do to support language and literacy development as well as socioemotional skills for dual language learners. The California competencies also are differentiated by the teachers’ linguistic skills (monolingual, bilingual, or biliterate), cultural background (monocultural or bicultural), and levels of experience.

Integrated technology into curricula Technology is everywhere: students in elementary schools are increasingly expected to develop digital literacy skills; technology and media have become nearly ubiquitous in the lives of

most families with young children; and professional information, curriculum materials, and children’s books already are being delivered digitally to schools and early childhood centers. Competency statements on technology may need to be two-pronged: (1) expressing expectations around the use of new tools by educators for professional communication, information sharing, and assessment; and (2) articulating more specifically what educators should know when using technology to teach young children, including the teaching of emergent digital literacy skills and the teaching of particular content or subject matter (see Chapter 6). The second prong should involve knowing how to be selective in adopting technology and interactive media products, and knowing how and under what conditions to use various technologies with young children effectively. In addition to the technology skills outlined by the NBPTS and InTASC, a joint position statement from the National Association for the Education of Young Children and the Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College provides guidance to educators in settings across the birth through age 8 spectrum (NAEYC and Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College, 2012). ZERO TO THREE has also developed guidelines specifically for children under 3 (Lerner et al., 2014).

Conclusion About Competencies for Educators

Having a role in the early learning of a child is a complex responsibility that requires a sophisticated understanding of the child’s cognitive and socioemotional development; knowledge of a broad range of subject-matter content areas; and skills for developing high-quality interactions and relationships with children, their families, and other professionals. The importance and value of these skills is often underestimated.

Conclusion About Core Competency Statements for Educators

A scan across national and state statements of core competencies for educators suggests that there is broad agreement on what educators who work with children from infancy through age 8 need to know and be able to do. However, there are variations in emphasis and gaps. Organizations and states that issue statements of core competencies for these educators would benefit from a review aimed at improving consistency in family engagement and assessment and enhancing their statements to reflect recent research on how children learn and develop and the role of educators in the process. Areas likely in need of enhancement in many existing statements include teaching subject-matter–specific content, addressing stress and adversity, fostering so-

cioemotional development, promoting general learning competencies, working with dual language learners, and integrating technology into curricula.

KNOWLEDGE AND COMPETENCIES FOR LEADERS AND ADMINISTRATORS

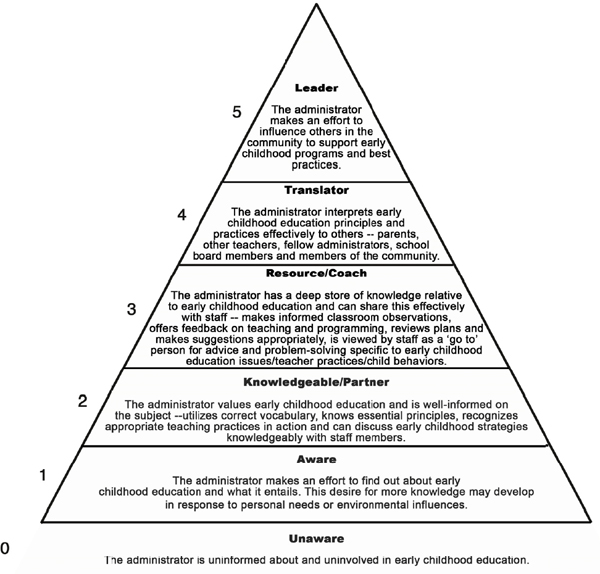

Elementary school principals, early learning center directors or program directors, family childcare owners, and other supervisors and administrators play an instrumental role in helping care and education professionals who work with young children strengthen their core competencies and in creating a work environment in which these professionals can fully use their knowledge and skills (see Figure 7-1 for a summary of levels of effective

FIGURE 7-1 Administrator’s contribution to care and education for young children.

SOURCE: Kostelnik and Grady, 2009, p. 26.

contributions from leadership).4 These leaders are an important factor in the quality of early learning experiences for the children in the settings they oversee. Principals and directors often take a lead role in selecting instructional content and activities for professional learning within their school, center, or program (Matsumura et al., 2010; Snyder et al., 2011).

In addition, leaders, including not only principals and directors but also superintendents and other administrators, have a major influence because they are responsible for workforce hiring practices. They need to be able to seek and hire educators with the appropriate and necessary knowledge and competencies to work with children in the settings they lead. While licensure/credentialing systems for educators are one tool to assess whether prospective candidates are qualified, leaders also need to know and be able to assess a wide range of characteristics that contribute to quality practice.

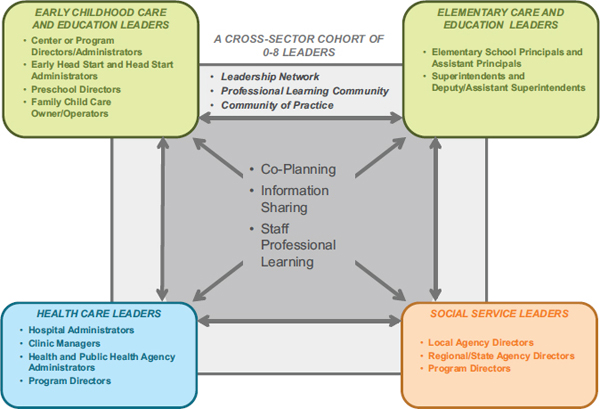

Leaders also serve as a point of linkage among different stakeholders, professionals, and settings (see Figure 7-2). By sharing information, planning together, and introducing shared professional learning for their staff, a cross-sector cohort of leaders can play an important role in facilitating the communication and collaboration necessary to improve both vertical continuity within the care and education sector and horizontal continuity with other sectors, such as health and social services (continuity is discussed further in Chapter 5).

The quality of leadership is connected to the quality of early learning for children. For example, the levels of education and specialized training for directors in center-based early learning programs are linked to program quality, as indicated by observations of the learning environment, instructional leadership practices, and program accreditation (McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, 2010, 2014). One meta-analysis of studies of K-12 schools showed a correlation between principals’ leadership behaviors and student achievement (Marzano et al., 2005), and a recent study found that effective principals can boost student achievement by an equivalence of 2-7 months in a school year (Branch et al., 2013).

While the importance of school and program leadership is unequivocal, the capacity of these leaders to support high-quality instruction and services in the early years is questionable. Early childhood center and program directors suffer from a lack of specialized training as early learning instructional leaders. Elementary school principals, because of the way they are prepared or recruited, often lack understanding of early childhood development research and best practices in instruction in preschool and the primary grades. The National Association of Elementary School Principals

_____________

4 Murphy (2003) also provides a useful outline of the role of an effective leader in promoting children’s academic success, although the focus is not specifically early childhood.

FIGURE 7-2 Leadership roles and connections.

has reported that more than half of practicing elementary school principals work in schools with prekindergarten programs serving children ages 3-4, and much of their knowledge about child development is self-taught (National Association of Elementary School Principals, 2014).

As a result of federal and state accountability policies that tend to focus on the academic performance of older students, elementary school principals have less immediate pressure to devote more attention to the earlier grades (Mead, 2011). One study of North Carolina elementary schools suggests that over time, tying high-stakes consequences to standardized test scores in grades 3 through 8 has caused principals to assign lower-quality teachers to the earlier grades (Fuller and Ladd, 2013). In another study on the extent to which principals use data from teacher evaluation systems to inform their personnel decisions (e.g., hiring, assignment, professional development), interviews with principals and district-level administrators in six urban districts and two charter school management organizations found that principals were assigning teachers they perceived to be poor to the early grades (Goldring et al., 2014).

The complexity of early childhood development discussed in earlier chapters and the sophisticated knowledge and competencies needed by early care and education professionals to be effective raise significant questions about the extent to which (1) school and program leaders are expected to have the capacity to support high-quality instruction and interactions in early childhood and early elementary settings, and (2) state and federal policies motivate and support these leaders in acquiring the knowledge and skills needed to fulfill that responsibility.

Perspectives from the Field

A leader’s job is multifaceted, and requires instructional and operational capabilities.

Leaders have an important role in incentivizing staff to seek professional learning supports and encouraging them to seek supports tailored to their individual needs.

The specific role of leaders as a “hub” between systems is particularly important, but requires that they learn competencies that they often currently do not have and that they receive support and are incentivized to make connections among leaders in early childhood education, early elementary, and other sectors, such as health.

————————

See Appendix C for additional highlights from interviews.

BOX 7-3

Knowledge and Competencies for Leadership in Settings with Children Birth Through Age 8

Practices to Help Children Learn

- Understanding the implications of child development and early learning for interactions between care and education professionals and children, instructional and other practices, and learning environments.

- Ability to keep current with how advances in the research on child development and early learning and on instructional and other practices inform changes in professional practices and learning environments.

Assessment of Children

- Knowledge of assessment principles and methods to monitor children’s progress and ability to adjust practice accordingly.

- Ability to select assessment tools for use by the professionals in their setting.

Fostering a Professional Workforce

- Knowledge and understanding of the competencies needed to work with children in the professional setting they lead.

- Ability to use knowledge of these competencies to make informed decisions about hiring and placement of practitioners.

- Ability to formulate and implement policies that create an environment that enhances and supports quality practice and children’s development and early learning.

- Ability to formulate and implement supportive and rigorous ongoing professional learning opportunities and quality improvement programs that

Core Competencies for Leadership

In addition to the foundational knowledge and competencies described for all adults who work with children (see Box 7-1), center directors, principals, and other leaders who oversee care and education settings for young children from birth through age 8 need both specific competencies and general competencies that overlap with those of the professionals they supervise. In Box 7-3, the committee identifies the competencies needed by these leaders.

Existing Statements of Leadership Competencies

A review of examples of statements of core leadership competencies from two early childhood organizations and two elementary education

-

reflect current knowledge of child development and of effective, high-quality instructional and other practices.

- Ability to foster the health and well-being of their staff and to seek out and provide resources that can help staff manage stress.

Assessment of Educators

- Ability to assess the quality of instruction and interactions, to recognize high quality, and to identify and address poor quality through evaluation systems, observations, coaching, and other professional learning opportunities.

- Ability to use data from assessments of care and education professionals appropriately and effectively to make adjustments to improve outcomes for children and to inform professional learning and other decisions and policies.

Developing and Fostering Partnerships

- Ability to support collaboration among the different kinds of providers under their leadership.

- Ability to enable interprofessional opportunities for themselves and their staff to facilitate linkages among health, education, social services, and other disciplines not under their direct leadership.

- Ability to work with families and support their staff to work with families.

Organizational Development and Management

- Knowledge and ability in administrative and fiscal management, compliance with laws and regulations, and the development and maintenance of infrastructure and an appropriate work environment.

leadership organizations suggests that there is a distinction between the stated expectations for these two categories of leaders whose professional roles fall within the birth through age 8 range.

- McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership Program Administration Competencies (Bloom, 2007)

- Head Start Director Core Competencies (Office of Head Start, 2008)

- National Association of Elementary School Principal Competencies for Leading pre-K-3 Learning Communities (National Association of Elementary School Principals, 2014)

- Council of Chief State School Officers Draft Standards for School Leaders (CCSSO, 2014)

Compared with competencies for educators, which show considerable agreement in the stated expectations, there is a more pronounced disconnect in expectations for leaders between elementary school settings and early childhood settings outside of elementary schools. Competency statements for leaders from organizations representing elementary school principals and chief state school officers are much more focused than those representing early childhood professions on knowledge and skills required for instructional leadership. Most of the NAESP and CCSSO competencies are related to leaders’ ability to create working environments and supports for educators that help them improve their instructional practice. In contrast, most of the competencies specified by the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership and Head Start have to do with how well a leader can develop and manage a well-functioning organization. In fact, the “Technical Competencies” described as part of the “core” for Head Start directors recommend only that directors have “general knowledge” of the content areas of the Head Start program performance standards and not necessarily of how they need to use that knowledge to support Head Start educators’ practice. The other skills described under “Technical Competencies” could be considered related more to organizational development and management than to instructional leadership.

This emphasis on organizational management for early childhood program leaders relates to an important aspect of their work. Many early childhood providers are essentially small businesses with minimal to no support infrastructure (compared with a school district). Therefore, it is important for leaders to get the business side of their job right. Yet, given the science of child development and early learning reviewed in Part II, the complex and sophisticated professional competencies needed by the practitioners in these settings, and the importance of the work environment in supporting quality professional practice, adequate attention also needs to be paid to the ability of leadership to support high-quality instruction.

CCSSO’s standards include some of the most specific mentions of child development and other principles that may be associated with early childhood research and best practices. For example, the standards state that leaders are expected to

- ensure that instruction is anchored in the best understandings of child development;

- emphasize assessment systems congruent with understandings of child development and standards of measurement;

- ensure that each student is known, valued, and respected;

- ensure that students are enmeshed in a safe, secure, emotionally protective, and healthy environment; and

- ensure that each student has an abundance of academic and social support.

Based on what is needed to foster the early learning of children, effective educational leadership in all settings needs to be driven by a common impetus, one that is articulated in the CCSSO standards as the expectation that leaders focus first and foremost on supporting student and adult learning.

Conclusion About Competencies for Leadership

The complexity of childhood development and early learning and the sophisticated knowledge and competencies needed by care and education professionals have important implications for the knowledge and competencies of leadership in settings for children from birth through age 8. These leaders and administrators need to understand developmental science and instructional practices for educators of young children, as well as the ability to use this knowledge to guide their decisions on hiring, supervision, and selection of tools for assessment of children and evaluation of teacher performance, and to inform their development of portfolios of professional learning supports for their settings.

Conclusion About Core Competency Statements for Leaders

To create a more consistent culture of leadership expectations better aligned with children’s need for continuous learning experiences, states’ and organizations’ statements of core competencies for leadership in elementary education would benefit from a review of those statements to ensure that the scope of competencies for instructional leadership encompasses the early elementary years, including pre-K as it increasingly becomes included in public school systems. States and organizations that issue statements of core competencies for leadership in centers, programs, family childcare, and other settings for early childhood education would benefit from a review of those statements to ensure that competencies related to instructional leadership are emphasized alongside administrative and management competencies.

KNOWLEDGE AND COMPETENCIES FOR INTERPROFESSIONAL PRACTICE

A critical competency for all professionals with roles in seamlessly supporting children from birth through age 8 is the ability to work in synergy, both across settings within the care and education sector and between the care and education sector and other closely related sectors, especially

health, mental health, and social services. The concept of interprofessional practice has been an increasing focus in the health sector, and many of the principles that have been developed in that sector apply as well to the care and education sector. The health sector also has recognized the interdependency between interprofessional practice and interprofessional education in creating a workforce prepared for collaborative practice as one way to improve the quality of health care services and ameliorate fragmentation in health systems (D’Amour and Oandasan, 2005; Frenk et al., 2010; WHO, 2010). This principle applies well to the challenges and professional learning needs that arise from the diffuse systems that make up the care and education sector (as described in Chapter 2).

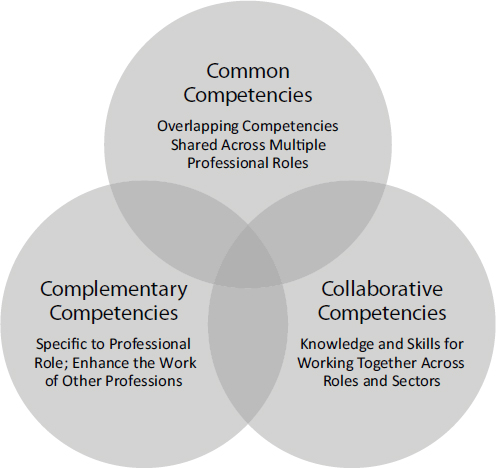

An increasing focus on interprofessional competencies in the health sectors provides useful groundwork for strengthening these competencies in the care and education sector. Barr (1998) distinguishes among “complementary” competencies that are specific to a professional role but enhance the qualities of other professionals in providing care; “common” or overlapping competencies expected of multiple professional roles in a sector (like those for educators in Box 7-2); and “collaborative” competencies that professionals use to work with one another within and across specialties and sectors, as well as with families and communities (Barr, 1998) (see Figure 7-3).

Core interprofessional collaborative competencies have been articulated for the health sector in four main areas: (1) values and ethics for interprofessional practice, (2) roles and responsibilities for collaborative practice, (3) interprofessional communication practices, and (4) interprofessional teamwork and team-based practices (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011).5 Competencies related to values and ethics for interprofessional and collaborative practice identify the importance of showing respect for patients and families, as well as a mutual trust and respect for team members, health professionals, and individual experts. Interprofessional ethics, an emerging component of interprofessional competencies, can help health professionals understand one another and facilitate working relationships among professions to provide collaborative care for patients.

The ability to communicate one’s own role and responsibilities and understand the roles and responsibilities of team members and other professionals is a key competency to facilitate cooperation, coordination, and col-

_____________

5 The Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel (2011) articulated interprofessional competencies that converge across those identified previously by professional health organizations and educational institution in the United States, as well as national and international literature. The full statement of competencies can be found at http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/ipecreport.pdf (accessed March 22, 2015).

FIGURE 7-3 Three types of interprofessional competencies.

SOURCE: Adapted from Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel,

2011.

laboration among the team and to address the needs of patients. Moreover, effective teamwork requires ongoing communication and learning which can aid in further defining the roles of each health professional. Thus, interprofessional communication is a competency domain that involves respectful communication with patients, families, and other health professionals. This competency involves communicating information using a common language that is understandable for patients and health professionals in other disciplines. Effective communication also requires listening and providing instructive and respectful feedback to help facilitate collaborative teamwork as well as considering how one’s levels of experience and expertise, culture, and power can impact working relationships.

The final interprofessional competency domain emphasizes components

of teamwork and team building, and ways in which health professionals can effectively collaborate on behalf of shared goals. Specific competencies include engaging other professionals and integrating their knowledge and expertise in a patient-centered effort. Professionals should also understand team development processes and recognize areas of improvement through individual and team reflection. Furthermore, professionals need to recognize that shared accountability and decision making requires “relinquishing some professional autonomy to work closely with others, including patients and communities, to achieve better outcomes” (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011, p. 24).

These core competencies embody a number of principles that also apply to what care and education professionals need to know and be able to do to work well both across roles and settings within the care and education sector and with professional colleagues in other sectors. Indeed, an analysis of competencies for school mental health professionals included several similarly applicable competencies for communication, collaboration, and data sharing across multiple systems (see Box 7-4) (Ball et al., 2010). For the health sector, these competencies were articulated to inform interprofessional practice as well as behavioral learning objectives for interprofessional education, with the intent that they would be used in parallel with specific and differentiated competencies within professions in the health sector (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011). A similar approach could be used to improve the acquisition and application of these skills in the training and practice of care and education professionals.

BOX 7-4

Competencies for Communication and Collaboration Across Systems

Communication and Building Relationships

- Demonstrates effective communication skills with school personnel, families, and community and other stakeholders.

- Collaborates with others in ways that demonstrate a valuing of and respect for the input and perspectives of multiple professionals and disciplines.

- Builds positive relationships with other school personnel, families, and the community.

- Participates effectively in teams and structures.

- Provides effective consultation services to teachers, administrators, and other school staff.

- Facilitates effective group processes (e.g., confl¡ict resolution, problem solving).

- Demonstrates knowledge of variances in communication styles.

- Identifies, describes, and explains the differing roles and responsibilities of other helping professionals working in and with schools.

Engagement in Multiple Systems and Cross-Systems Collaboration

- Collaborates with families in support of healthy student development.

- Collaborates effectively within and across systems.

- Values the input and perspectives of multiple stakeholders.

- Identifies and knows the protocols for accessing various school- and community-based resources available to support overall school success and promote healthy student development.

- Effectively navigates school-based services through appropriate prereferral and referral processes.

- Participates effectively in planning, needs assessment, and resource mapping with families and school and community stakeholders.

- Coordinates and tracks the comprehensive services available within the community to support healthy student and family development.

Data Use

- Uses clear and effective protocols to assist in sharing and using data for decision making.

SOURCE: Adapted from Ball et al., 2010.

Alliance for a Better Community. 2012. Dual language learner teacher competencies (DLLTC) report. Los Angeles, CA: Alliance for a Better Community.

Ball, A., D. Anderson-Butcher, E. A. Mellin, and J. H. Green. 2010. A cross-walk of professional competencies involved in expanded school mental health: An exploratory study. School Mental Health 2(3):114-124.

Barr, H. 1998. Competent to collaborate: Towards a competency-based model for interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care 12(2):181-187.

Bloom, P. J. 2007. From the inside out: The power of reflection and self-awareness, Director’s toolbox. Lake Forest, IL: New Horizons.

Branch, G. F., E. A. Hanushek, and S. G. Rivkin. 2013. School leaders matter: Measuring the impact of effective principals. Education Next 13(1):62-69.

California Department of Education and First 5 California. 2011. California early childhood educator competencies. Sacramento: California Department of Education.

CCSSO (Council of Chief State School Officers). 2011. Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (INTASC): Model core teaching standards: A resource for state dialogue. Washington, DC: CCSSO.

———. 2014. 2014 Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium (ISLLC) draft standards. Washington, DC: CCSSO.

D’Amour, D., and I. Oandasan. 2005. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: An emerging concept. Journal of Interprofessional Care 19:8-20.

DEC (Division for Early Childhood). 2014. DEC recommended practices in early intervention/early childhood special education 2014. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children.

Frenk, J., L. Chen, Z. A. Bhutta, J. Cohen, N. Crisp, T. Evans, H. Fineberg, P. Garcia, Y. Ke, P. Kelley, B. Kistnasamy, A. Meleis, D. Naylor, A. Pablos-Mendez, S. Reddy, S. Scrimshaw, J. Sepulveda, D. Serwadda, and H. Zurayk. 2010. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 376(9756):1923-1958.

Fuller, S. C., and H. F. Ladd. 2013. School based accountability and the distribution of teacher quality across grades in elementary school, working paper 75. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Goldring, E. B., C. M. Neumerski, M. Cannata, T. A. Drake, J. A. Grissom, M. Rubin, and P. Schuermann. 2014. Summary report: Principals’ use of teacher effectiveness data for talent management decisions. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Peabody College.

Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. 2011. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

Kostelnik, M. J., and M. L. Grady. 2009. Getting it right from the start: The principal’s guide to early childhood education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Lerner, C., and R. Barr. 2014. Screen sense: Setting the record straight. Research-based guidelines for screen use for children under 3 years old. Washington, DC: Zero to Three.

Marzano, R. J., T. Waters, and B. A. McNulty. 2005. School leadership that works from research to results. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Matsumura, L., H. Garnier, and L. Resnick. 2010. Implementing literacy coaching: The role of school social resources. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 32(2):249-272.

McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership. 2010. Research notes. Connecting the dots: Director qualifications, instructional leadership practices, and learning environments in early childhood programs. Wheeling, IL: National Louis University, McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

———. 2014. Leadership matters. Wheeling, IL: National Louis University, McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

Mead, S. 2011. PreK-3rd: Principals as crucial instructional leaders. New York: Foundation for Child Development.

Murphy, J. 2003. Leadership for literacy: Research-based practice, preK-3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2009. NAEYC standards for early childhood professional preparation. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

NAEYC and Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College. 2012. Technology and interactive media as tools in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

National Association of Elementary School Principals. 2014. Leading pre-K-3 learning communities: Competencies for effective principal practice, executive summary. Alexandria, VA: National Association of Elementary School Principals.

NBPTS (National Board for Professional Teaching Standards). 2012. Early childhood generalist standards, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: NBPTS.

NCTSN (National Child Traumatic Stress Network) Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force. 2012. The 12 core concepts: Concepts for understanding traumatic stress responses in children and families. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: UCLA-Duke University National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

New Hampshire Department for Health and Human Services and Child Development Bureau. 2013. New Hampshire’s infant and toddler workforce specialized competencies. http://www.dhhs.state.nh.us/dcyf/cdb/documents/infant-toddler-competencies.pdf (accessed March 17, 2015).

New Mexico Early Childhood Higher Education Task Force. 2011. Common core content and competencies for personnel in early care, education and family support in New Mexico: Entry level through bachelor’s level. Santa Fe, NM: New Mexico Children, Youth and Families Department.

New York State Association for the Education of Young Children. 2009. New York state infant toddler care and education credential competencies. http://nysaeyc.org/wp-content/uploads/ITCEC-Competencies.pdf (accessed March 17, 2015).

Office of Head Start. 2008. Head Start director core competencies. http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/tta-system/operations/leadership/HeadStartDirect.htm (accessed March 6, 2016).

Ohio Child Care Resource & Referral Association. 2008. Standards of care & teaching for Ohio’s infants & toddlers. http://occrra.org/it/documents/ITStandards.pdf (accessed March 17, 2015).

Snyder, P. A., M. K. Denney, C. Pasia, S. Rakap, and C. Crowe. 2011. Professional development in early childhood intervention: Emerging issues and promising approaches. In Early childhood intervention: Shaping the future for children with special needs and their families (Vols. 1-3), edited by C. Groark and L. A. Kaczmarek. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger/ABC-CLIO. Pp. 169-204.

Vermont Northern Lights Career Development Center. 2013. Core knowledge areas and competencies for early childhood professionals: The foundation for Vermont’s unified professional development system. Montpelier: Vermont Northern Lights Career Development Center.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva: WHO.

This page intentionally left blank.