Children are already learning at birth, and they develop and learn at a rapid pace in their early years, when the environments, supports, and relationships they experience have profound effects. Children’s development from birth through age 8 is not only rapid but also cumulative. Early learning and development provide a foundation on which later learning is constructed, and consistency in high-quality learning experiences as children grow up supports continuous developmental achievements. The adults who provide for the care and education of young children bear a great responsibility for their health, growth, development, and learning, building the foundation for lifelong progress. Young children thrive and learn best when they have secure, positive relationships with adults who are knowledgeable about how to support their health, development, and learning and are responsive to their individual progress. Indeed, the science of child development and of how best to support learning from birth through age 8 makes clear what an important, complex, dynamic, and challenging job it is for an adult to work with young children in each of the many professional roles and settings where this work takes place.

Even though they share the same objective—to nurture young children and secure their future success—the various professionals who contribute to the care and education of children from birth through age 8 are not perceived as a cohesive professional workforce. Those who care for and teach young children do so in disparate systems with a variety of backdrops and circumstances. The requirements for their preparation and credentials often depend on the setting where they work rather than on the needs of children. They work in homes, childcare centers, preschools, educational programs,

and elementary schools. Their work relates directly to those who provide services such as home visiting, early intervention, and special education, and is also closely connected to the work of pediatric health professionals and social services professionals who work with children and families.

Growing public understanding of the importance of early childhood is reflected by an increased emphasis on this age group in policy and investments. Yet the sophistication and complexity of the professional roles that entail working with children from infancy through the early elementary years are not recognized and reflected consistently in practices and policies regarding education and other expectations for qualification to practice, professional learning expectations and supports, and compensation and other working conditions. Those who care for and educate young children currently are not acknowledged as a workforce unified by their common objective and shared contributions to the development and early learning of young children and the common knowledge base and competencies needed to do their jobs well.

STUDY CHARGE, SCOPE, AND APPROACH

Over the past several decades, much has been learned about the rapid development of critical neurological and biological systems in the earliest years and about the important foundation that is laid through the early experiences of children. Considerable work also has been done to examine the interventions, programs, policies, and systems that have been implemented or are needed to have a positive influence on young children in early life and for the long term. Over time, these efforts increasingly have addressed important topics related to early childhood in a frame that is inclusive of children from birth through age 8. This age span is not a discrete developmental period with precise boundaries at its margins; indeed, it falls on a developmental continuum that encompasses individual variations and that begins before birth and continues after age 8 into the rest of childhood, through adolescence, and throughout the life course. Nonetheless, focusing on this specific age span within this continuum is important because it is a range in which a troubling disconnect currently exists.

This age span is a window during which development is progressing at a particularly rapid pace, and experiences during the first 8 years of life shape a child’s long-term trajectory. In this window, children benefit from consistent, cumulative learning experiences and other influences that build on each other and evolve as children age. Yet just when children would benefit most from consistency and continuity, the systems with which they interact and the professionals who work with them are particularly fragmented and disjointed. By third grade, a child has entered the education system that will guide her or him for nearly the next decade, having

previously been prepared by formal and informal learning opportunities beginning from birth. However, both early learning opportunities and the education system that most commonly follows often fail to support children seamlessly, on a consistent, cumulative trajectory free from disruptive transitions, to position them for their future academic achievements and success in life.

Many factors influence child development during this window of time, including, for example, the availability of and equitable access to the wide range of services and programs that are or could be provided for children and their families; the funding and financing that affect the allocation of resources to and among those services and programs; the quality of their implementation on a large scale; the policies for their oversight, evaluation, and accountability; and the degree to which they are coordinated and interact across settings and sectors. Improvements and progress across all of these factors will be important to promote the development and early learning of all children from birth through age 8. However, none of these improvements will be truly effective without concerted attention to the adults who work with children. Effort in this area is one of the most important mechanisms available for improving the quality of the care and education received by young children; providing information, support, and links to resources as these professionals interact with families and with each other; and ultimately, improving outcomes for children. This study was commissioned specifically to focus on the science of development and early learning not just for what it reveals about children, but in particular for its implications for the professionals who work with children during this critical period. These implications apply to the knowledge and competencies these professionals need; their systems for professional learning; and other supports that contribute to improving the quality of professional practice and developing an excellent, robust, and stable workforce across the many professional roles that relate to children from birth through age 8. This dual focus on the science of learning and the development of the workforce is central to ensuring that all children get a good start in life.

Study Charge

The full statement of task for the Committee on the Science of Children Birth to Age 8: Deepening and Broadening the Foundation for Success is presented in Box 1-1. In summary, the committee was charged with examining how the science of children’s health, learning, and development can inform how the workforce supports children from birth through age 8. Areas of emphasis included the influence of neurobiology, health, and development on learning trajectories and educational achievement, as well as on workforce considerations such as standards, expectations, and

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee will conduct a study and prepare a consensus report on how the science of children’s health, learning, and development from birth through age 8 can be employed to inform how we prepare a workforce to seamlessly support children’s health, development, learning, and school success from birth through age 8, including standards and expectations, instructional practices, preparation and professional development, and family engagement across diverse contexts (e.g., rural/urban) and populations (e.g., special education, immigrant, dual language learners, sub-threshold children). The committee will address the following questions:

- What do we know about the influence of neurobiology, health, and development (e.g., emotion regulation, executive functioning, psychosocial) on learning trajectories and educational achievement for children from birth through age 8, including typical and atypical pathways?

- What generalized and specialized knowledge, skills, and abilities do adults, working with children across the birth through age 8 continuum and across infant, toddler, preschool-aged, and K-3 settings (for example, home visitors, childcare workers, early childhood educators, health professionals, center directors, elementary school teachers, principals) need to seamlessly support children’s health, learning, development, and school success?

- What staff development structure and qualifications are necessary for educators at each level (e.g., entry level, full professional, etc.) to support children’s learning across the continuum of development from birth through age 8? This should be linked to question 2.

qualifications; generalized and specialized knowledge and competencies; instructional practices; professional learning; leadership; and family engagement. The committee was tasked with looking across diverse contexts and populations and across professional roles and settings to draw conclusions and make recommendations about how to reenvision professional learning systems and inform policy decisions related to the workforce in light of the science of child development and early learning and the knowledge and competencies needed by the adults who work with children from birth through age 8. The statement of task specifies a wide range of audiences for the report, such as federal funding agencies, state and local agencies, regulatory agencies, federal and state legislatures, institutions of higher education, and programs and practitioners that serve children birth through age 8.

As noted above, one critical factor that influences child development from birth through age 8 is the availability of resources to invest in any

- How can the science from questions 1 and 2 be employed to reenvision preparation and professional development programs across infant, toddler, preschool-aged, and K-3 settings, including how to assess children and use data to inform teaching and learning from birth through age 8?

- How can the science on children’s health, development, learning, and educational achievement, and the skills adults need to support them, inform policy decisions conducive to implementing the recommendations?

Based on currently available evidence, the report could include findings, conclusions, and recommendations on the above, paying particular attention to research on (1) poverty, racial inequities, and disadvantage; (2) learning environments in the home and in schools; (3) adult learning processes as they relate to teaching children; and (4) leadership/management skills as they relate to developing the skills of a highly effective workforce designed to support children’s learning, growth, and development from birth through age 8. The report will provide research and policy recommendations to specific agencies and organizations (governmental and nongovernmental) as well as inform institutions serving children birth through age 8. Recommendations will be geared toward the following, including recommendations for joint actions among agencies, institutions, and stakeholders: federal funding agencies, including the Administration for Children and Families, the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Education, with a particular emphasis on Title II of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (Title II), which focuses on improving teacher and principal quality; legislatures (Congress, state legislatures); higher education institutions; state and local education agencies; state early childhood care and education agencies; family childcare programs; regulation agencies; and practitioners that provide health, education, and care services to children birth through age 8.

potential changes, most of which will require significant allocation of new or reallocation of existing resources. While acknowledging that the availability of resources is an important reality that would affect the feasibility of the committee’s recommendations, the sponsors specified in clarifying the study charge that this committee not conduct analyses or develop consensus conclusions and recommendations addressing funding and financing. The sponsors did not want the committee to be swayed by foregone conclusions about the availability of resources in interpreting the evidence and the current state of the field and in carrying out deliberations about its recommendations. The sponsors also recognized that the breadth of expertise required to fulfill such a broad and comprehensive charge precluded assembling a committee with sufficient additional breadth and depth of expertise in economics, costing and resource needs assessment,

financing, labor markets, and other relevant areas to address funding and financing issues.1

Study Scope

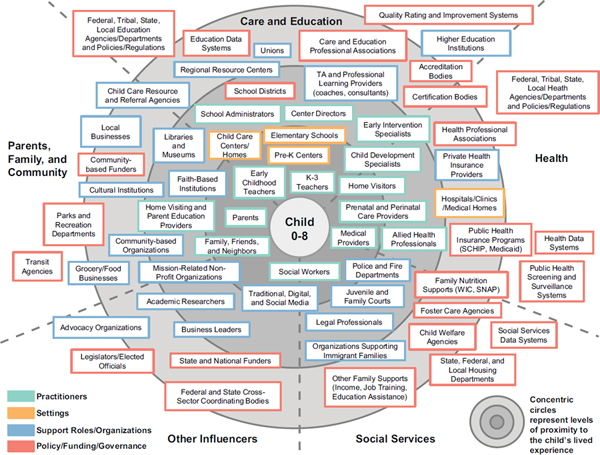

The landscape of influences on and opportunities for a child’s development and early learning is complex and encompasses many interrelated settings, services, and stakeholders. Figure 1-1 shows illustrative examples within the main categories of care and education; health; parents, family, and community; and other influences. While overwhelming and perhaps even intimidating, this is nonetheless the reality of the environment in which efforts to improve the quality of professional practice and support for the workforce will be implemented. This landscape is explored in greater depth in Chapter 2, with a focus on the care and education sector.

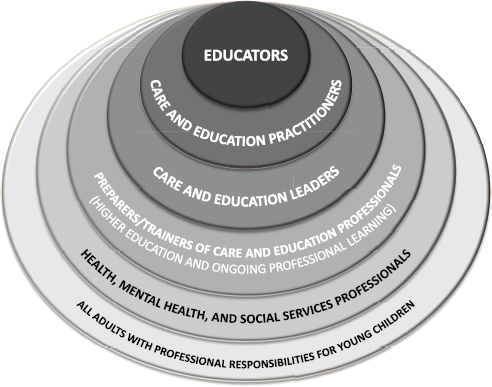

Many adults interact with children within this complex landscape, and every interaction a child has with an adult is an opportunity for a learning experience. Yet it was not possible for a single consensus study to cover in depth every adult role with the potential to influence child development and early learning within this landscape. The emphasis specified in the committee’s statement of task is on learning and educational achievement, instructional practices, and educators. Therefore, the committee chose to focus on professionals who work in the care and education sector, and to a lesser extent on those in the health and social services sectors who intersect closely with the care and education sector. That said, the findings and conclusions in this report about foundational knowledge and competencies are applicable broadly for all adults with professional responsibilities for young children.

When this report delves into specialized competencies and the implications for professional learning and workforce development, the major focus is on those professionals who are responsible for regular, daily care and education. In many cases, the committee’s review was also inclusive of or applicable to closely related care and education professions who see children somewhat less frequently or for periodic or referral services, such as home visitors, early intervention specialists, and mental health consultants. In addition, it encompassed considerations for professionals in leadership positions and those who work in the training, education, and professional development of the care and education workforce, as well as for the interactions of care and education professionals with closely related practitioners

_____________

1 Personal communications between sponsor representatives and Institute of Medicine (IOM)/National Research Council (NRC) staff during contract negotiations and between sponsors and committee members during a public information-gathering session held on December 19, 2013.

FIGURE 1-1 The complex landscape that affects children ages 0-8.

NOTE: SCHIP = State Children’s Health Insurance Program; SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

who work with children aged 0-8 and their families in the health and social services sector. Figure 1-2 summarizes the study’s scope of inclusion for different professional roles.

Finally, as specified in the statement of task, the committee’s major focus was on the competencies and professional learning that, to support greater consistency in high-quality learning experiences for children, need to be shared among care and education professionals across the birth through age 8 continuum and across professional roles and practice settings. This focus included areas in which care and education professionals will benefit from understanding the scope of learning—and the scope of educational practices—for the settings and ages that precede or follow them within the birth through age 8 range. Although further specialized competencies and professional learning differentiated by age, setting, and/or role are important, this study was not intended to duplicate or supplant existing infrastructure or processes for articulating, reviewing, and guiding

FIGURE 1-2 Illustration of the study’s scope of inclusion for different professional roles, with the specificity and depth of focus decreasing from the innermost/darkest rings to the outermost/lightest rings.

those competencies. Those further competencies require greater depth of representation for each age range and professional role than was feasible with a committee composed to be broadly representative in its expertise across the entirety of its broad charge. Rather, this committee’s task was to bridge those efforts by providing information and recommendations to assist each such effort in contributing collectively and more effectively to greater consistency and continuity for children.

It is important to acknowledge that parents (or other designated primary caretakers or guardians) and other family members are the most important adults in the life of most young children, with the potential to make the largest contribution to the child’s future success. Given the study charge to focus on the professional workforce, this report does not cover interventions to support or educate parents, but it does cover the role of care and education professionals in engaging and collaborating with families. An ongoing study and forthcoming report of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the National Research Council (NRC) will focus on strengthening the capacity of parents of young children from birth through age 8.2

Terminology

Selected key terms used broadly throughout this report are described here. Other terms that appear less frequently in the report that may be ambiguous or used in different ways in different fields are explained when first introduced in the chapter in which they appear.

Professional roles The terminology used to describe professional roles within the care and education sector varies widely based on setting, tradition, and emerging—but not always consistent—preferences from within the field itself. For this report, the committee selected some terms to use consistently whenever possible, with the aim of using terms that would be generally inclusive across subspecialized roles and reflect the shared value and importance across roles, and avoiding terms that sometimes are perceived as implying differing value for different roles.

To refer inclusively and collectively to the overall care and education workforce, this report uses the term “care and education professionals.” To refer to professionals with regular (daily or near-daily), direct responsibilities for the care and education of young children, this report uses the terms “educators,” which includes educators in childcare settings and centers that span ages 0 through 8, as well as preschools and elementary schools. To refer to closely related professions such as home visitors, early intervention

_____________

2 More information about this study can be found at www.iom.edu/activities/children/committeeonsupportingtheparentsofyoungchildren.

specialists, and mental health consultants, who may not have the same frequency of direct interaction with a child as educators but are closely linked to the professional practice of the educators who do, the report uses either the term used for the specific role or, collectively with educators, “care and education practitioners.” The term “practitioners” also is used broadly to denote professional roles in the health and social services sectors.

As noted above, this report encompasses those in leadership roles, such as center directors, principals, and administrators, as an important part of the care and education workforce, and therefore includes some review of implications for their professional practice, professional learning, and workforce development. These roles are generally referred to as “leaders” or, collectively with the overall care and education workforce, as “care and education professionals.”

Professional learning This report uses the term “professional learning” to describe all of the various mechanisms that can contribute to ensuring that the early care and education workforce has what it needs to gain and reinforce necessary knowledge and competencies for quality practice that will foster continuous progress in the development and early learning of children from birth through age 8. Chapter 8 provides a detailed overview of this conceptualization of professional learning.

Systems This report uses the term “systems” to describe the many interrelated elements—such as institutions, organizations, stakeholder groups, and policies—that contribute to services for young children and affect the adults who work with them. The term encompasses both “systems” as complex wholes and specified subsets (such as “professional learning systems” or “licensure systems”).

Finally, it should be noted that this report uses terms consistently whenever possible. However, there are some exceptions. In some cases, for example, where a finding or discussion is specific to a more narrow professional role, the specific term for that role is used (e.g., “home visitor”). In other cases, where a source document uses a different term from that selected by the committee and it is not clear whether the committee’s term would accurately reflect the intent of the authors, the source term is retained.

Study Approach

The committee met five times to deliberate in person, and conducted additional deliberations by teleconference and electronic communications. Public information-gathering sessions were held in conjunction with the committee’s first, second, and third meetings and in three locations across

the country; the complete agendas for these sessions can be found in Appendix B. The committee also conducted interviews and site visits in three locations. Additional interviews were conducted by a consultant team to inform a mapping of systems and stakeholders in the care and education and related sectors and to explore professional learning in greater depth with relevant stakeholders. Interview participants and themes from the interviews and site visits are listed in Appendix C. The committee also had the opportunity to gather information from and engage in discussions with practitioner advisors who served as consultants for this study; these individuals are listed in the front of this report.

The committee reviewed literature and other documents from a range of disciplines and sources.3 Comprehensive systematic reviews of all primary literature relevant to every aspect of the study’s broad charge was not within the study scope. To avoid replication of existing work, the committee sought relevant high-quality reviews and analyses. Where these were available, the report includes summaries of their key findings, but otherwise refers the reader to the available resources for more detailed information. In specific topic areas where existing reviews and analyses were insufficient, the committee and staff conducted targeted or systematic literature and document searches. This report therefore builds on a large body of previous work. Indeed, several prior reports of the IOM and the NRC provide more detailed review and analysis specific to subcomponents of what is covered in this report (see Box 1-2).

Applying this approach to review the existing body of work revealed some gaps in the evidence base and led to the identification of some important research areas, which are listed in Chapter 12. However, the committee does not intend its highlighting of ongoing research needs to be taken as suggesting inaction; rather, the report provides a framework for immediate actions that are sound and well supported based on the available research findings. The committee’s aim is to offer an ambitious yet pragmatic analysis and agenda for action with real potential for implementation in the

_____________

3 In developing the statement of task for this study, the sponsors elected to manage the already broad scope of work and range of required expertise by limiting the study’s consideration of programs and policies for workforce development and support for young children to the United States, given that this is the policy and implementation environment for the committee’s recommendations. However, there is also much relevant research and practice-based experience from international settings outside the United States. Of direct relevance to the topic of this report, for example, the interested reader is referred to Preparing Teachers and Developing School Leaders for the 21st Century: Lessons from Around the World, a report of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (http://www.oecd.org/site/eduistp2012/49850576.pdf, accessed March 24, 2015). In addition, readers may be interested in following the work of the IOM’s ongoing Forum on Investing in Young Children Globally. More information can be found at www.iom.edu/activities/children/investingyoungchildrenglobally.

BOX 1-2

Related Reports of the Institute of Medicine

and the National Research Council

Eager to Learn: Educating Our Preschoolers (2000)

Educating Teachers of Science, Mathematics, and Technology: New Practices for the New Millennium (2000)

From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development (2000)

How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition (2000)

Early Childhood Development and Learning: New Knowledge for Policy (2001)

Knowing What Students Know: The Science and Design of Educational Assessment (2001)

Testing Teacher Candidates: The Role of Licensure Tests in Improving Teacher Quality (2001)

Learning and Instruction: A SERP Research Agenda (2003)

Strategic Education Research Partnership (2003)

Early Childhood Assessment: Why, What, and How (2008)

Mathematics Learning in Early Childhood: Paths Toward Excellence and Equity (2009)

Preparing Teachers: Building Evidence for Sound Policy (2010)

Incentives and Test-Based Accountability in Education (2011)

Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century (2012)

Improving Measurement of Productivity in Higher Education (2012)

_____________

NOTE: All reports are available for free download at www.nap.edu.

context of the complexities of the heterogeneity and variability of different communities.

The various professionals who care for and teach young children from birth through age 8 currently do so in disparate settings and systems under a variety of circumstances while coming from different backgrounds. The expectations and requirements for their professional practice vary depending on their practice setting. Each of these professional roles and settings has variations in pathways for training, professional learning systems, requirements and systems for licensure and credentialing, and other policies for oversight and accountability. The implications of this varied and complex landscape are discussed in greater depth throughout this report.

To provide an overview here as context for the report, this section briefly reviews the historical origins of different workforce roles and some of the major challenges that must be met to arrive at a more convergent approach to caring for and teaching young children, one that allows for greater consistency and continuity from birth through elementary school settings.

The current professions, settings, and systems that contribute to the care and education of children from birth through age 8 in the United States have their roots in five distinct traditions: (1) childcare, (2) nursery schools, (3) kindergartens, (4) compensatory education, and (5) compulsory education at the primary level (see Table 1-1). For many years, these traditions

TABLE 1-1 Historical Traditions in the United States for Professions, Systems, and Settings for the Care and Education of Children from Birth Through Age 8

| Childcare | Childcare centers were established in the United States primarily to provide safe and secure settings for young children while their parents are at work. Childcare practices are historically grounded more in public health and child protection traditions than in education traditions. Many federal funding streams and state licensing for childcare programs still reflect this historical aim of subsidizing safe childcare to enable adult workforce participation rather than orienting primarily to providing an early learning environment for children (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009). |

| Nursery Schools | Historically, nursery schools in the United States were established to provide supplemental early learning experiences to children below school age. Children attending nursery schools were primarily from middle- and upper-class families. The aim was to nurture children’s social, emotional, physical, and intellectual development, and nursery school teachers were responsible for engaging children in activities that aligned with their interests and provided opportunities for creative expression, project work, and the use of natural materials (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009). |

| Kindergartens | In its early history in the United States, kindergarten, funded through philanthropy, was primarily intended to provide classroom learning, health services, home visits, and other assistance to children living in poverty and their families. Although kindergarten has moved over time into elementary schools, originally it functioned as a transition between home-based care and formal schooling and focused on play, self-expression, social cooperation, and independence. While the original emphasis was on development in social and emotional domains, over time, kindergarten began also to incorporate content-based learning as well as mathematics and literacy skill development (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009). |

| Compensatory Education | Compensatory programs provide services to children and their families who experience developmental, socioeconomic, or environmental circumstances that can negatively affect child development, such as poverty or disability. Examples in the United States include federally mandated programs under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act as well as Head Start, which provides prekindergarten for young children from low-income families. The learning environments in these programs are influenced by other care and education traditions, and as they have become well established, these programs have also influenced other settings and services (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009). |

| Compulsory Education |

Originally schooling in the United States varied greatly, including private institutions, church-sponsored schools, charity schools for low-income families, local schools created by parents, private tutors, and boarding schools for children from wealthy families, among others. Due to the disjointed and uncoordinated approach, schooling was inconsistent and inequitable, with some children having limited access to opportunities to learn. A publicly funded, locally governed, universal system was established as a result of education reform movements. As described by Kostelnik and Grady (2009, pp. 48-49), the purpose of this compulsory education was

|

| At present, about half of states require children to attend school by age 6, while for some the minimum age is 5 and for others is it as old as 8 (ECS, 2005; Snyder and Dillow, 2011, Tables 174, 175, and 176). | |

proceeded along relatively separate paths, which led to different roles, different entry points for working in those roles, and different pathways and modes of professional preparation and ongoing professional learning. As efforts emerge to help these traditions converge, the different philosophies and historical perspectives associated with each may complement one another or clash, and in any case they all influence today’s dialogue about the care and education of young children and the role of the workforce that provides it.

Although the care and education traditions described in Table 1-1 each have their own histories, philosophies, and perspectives, they often are thought of in two major categories: preprimary education and elementary

education. As summarized by Kostelnik and Grady (2009, p. 57), each of these brings different assets and qualities that can strengthen a convergent approach for the birth through age 8 continuum, and there are also many shared assets across the traditions:

- Preprimary education has a long history of

- – working with very young children,

- – educating the whole child,

- – working in teams,

- – working with families,

- – identifying children with special needs early on,

- – integrating children with special needs into classrooms with typically developing children, and

- – deriving programs and curricula based on studies of child development.

- Elementary education has a long history of

- – providing access to all children regardless of race, income, ability, or language;

- – providing auxiliary services to supplement children’s educational needs;

- – rallying the community to come together on behalf of children;

- – aligning curriculum from one level to the next;

- – addressing issues of accountability;

- – helping children and families make the transition from kindergarten to first grade; and

- – deriving programs and curricula, typically organized by distinct subject-matter content, based on studies of pedagogy and teacher practice.

- Both preprimary education and elementary education have a long history of

- – public service,

- – working with multiple funding streams,

- – working with community partners,

- – drawing on research to shape professional practice, and

- – professional organizations that support their members.

A more recent development is the growing emergence of preschool in public education. Head Start, created in 1965, is the first publicly funded preschool program for children from low-income families. Because there was much interest in but a lack of funding for Head Start, a few states started similar programs for students from low-income families during the

1980s (K-12 Academics, 2014). The first National Education Goal4 and the three accompanying objectives acknowledged that “the well-being of young children is a shared responsibility of family and society” and stated that “all children will have access to high-quality and developmentally appropriate preschool programs that help prepare them for school” (Kagan et al., 1995, p. 1).

Since then, publicly funded universal preschools have been emerging, although tuition remains the primary source of funding for most preschool programs. As of 2008, 38 states and the District of Columbia financed some prekindergarten programs, while many school districts used local and federal funds to implement preschool services (Barnett et al., 2009; Wat and Gayl, 2009). Currently, several states, including Florida, Georgia, Illinois, New York, Oklahoma, and West Virginia, are considering legislation to provide or already have universal preschool for all 4-year-olds. Illinois has a universal preschool program that also serves 3-year-olds. For children not in public preschools, there are multiple options: federally funded Head Start for eligible families; for-profit and not-for-profit providers, some of which accept government subsidies for low-income families; and government-funded special education programs (K-12 Academics, 2014).

Major Challenges to Navigate5

The field of early care and education has experienced a number of sometimes divisive issues. Following is a sample of some of the major challenges that must be navigated to promote a more unified workforce with a more convergent approach to caring for and teaching young children from birth through age 8, an approach that allows for greater consistency and continuity from birth through elementary school settings.

Differential Realities Related to Resources

Limited resources can be a challenge in all education settings. Public education has the stability of public financing, but resources are not always adequate to the need and are not distributed evenly. In particular, when public education is funded by property taxes, families living in poverty will most likely have schools with fewer resources, meaning lower-quality public schools and lower-quality learning experiences in the early elementary years, contributing to a cycle of disparity in education and achievement.

_____________

4 The National Education Goals were established in 1990 by the president and state governors.

5 The discussion in this section is based in part on Kostelnik and Grady, Getting It Right from the Start—the Principal’s Guide to ECE.

In early childhood settings outside of public school systems, the variability in funding streams and the lack or unpredictability of sustained funding mean that resource limitations are even more problematic. These other settings for educating young children rely on a multitude of sources, including federal, state, and local governments; nongovernmental funds such as private business and philanthropic resources; and out-of-pocket payments for childcare and education. As a result, there are disparities in the level of funding available among counterparts within the field.

One consequence of divergent financing mechanisms is that programs sometimes view each other as competitors for limited resources. For example, both Head Start and school-based preschool programs are required to demonstrate enrollment numbers in order to receive funding, and they are often in competition for the same population of students. Private providers and programs, which often rely heavily on out-of-pocket payments and in some cases subsidies, may feel that their role in the community and their client base is undermined by the emerging availability of public programs. The sense of a competitive care and education environment hinders the development of a system that fosters coordination and collaboration to ease transitions among settings and support continuity of high-quality learning experiences for children (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009).

Historical Schism Between Childcare and Early Education

Although it is common to group the workforce as preprimary and elementary education, it is important to recognize the challenges that have resulted as childcare and other forms of preprimary early childhood education have developed relatively independently of one another and with different purposes in mind (see Table 1-1). Policies for education programs and childcare, with their differing origins, often lack coordination and alignment around a comprehensive vision that encompasses the multiple aims of keeping children safe and healthy, providing them with high-quality learning experiences, and enabling their parents to be available to work. The disconnect among systems affects elements associated with the quality of learning experiences, such as teacher and administrator qualifications and standards for program quality and oversight. It also poses a challenge to developing mutual understanding and cooperation among professionals across systems (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009).

Differences in Professional Learning, Compensation, and Status

Those care and education professionals who work in early childhood settings outside of elementary schools and those who work in public and other school systems experience major differences in educational expecta-

tions as well as in the available systems for both preparation and professional learning during ongoing practice. The preprimary workforce has still nascent and highly diffuse professional learning systems, whereas the early elementary workforce is part of a much more regulated and established system for preparing and licensing K-12 teachers. In addition, many of the same issues that divide the workforce also divide those who provide their professional learning.

Discrepancies among compensation for different kinds of educators can lead to “informal (but powerful) hierarchies in which some individuals clearly have lower status than others,” which can create contention in working environments and hinder professionalism, respect, and collaboration among colleagues with an otherwise common purpose of supporting children’s early learning (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009, p. 55).

Assumptions and Perceptions of Divergence in Philosophies About Appropriate Instructional Practices and Outcomes for Children

There are some divisive issues related to educational philosophies and instructional practices among the different historically defined education traditions. These issues sometimes reflect actual differences in professional practices, but in some cases are also fueled by assumptions or misperceptions. These assumptions and misperceptions are compounded by the lack of mutual understanding and collaborative relationships across settings or the fact that various groups in the field tend not to see one another as colleagues with common purposes. Three examples are presented below:

- Many preprimary educators fear that preschools located in the public schools will place too great an emphasis on a narrow range of academic skills, will lose their focus on whole-child learning, and will reduce or eliminate time for play. Over the years, kindergarten has transformed from a “children’s garden” for play, learning, and discovery to a “mini-first grade.” This shift involves stricter schedules with long periods for group instruction, reducing or eliminating recess and play time, and removing play equipment (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009). Many early childhood educators are concerned that preschool will experience a similar transformation. Currently, many kindergarten teachers expect their students to enter the classroom knowing letters, numbers, and colors, and believe that literacy and mathematics instruction should begin in preschool or kindergarten. A major concern voiced by early childhood educators is that school-based preprimary programs will move in directions they consider developmentally inappropriate and inconsistent with

-

high-quality programming for young children (Bassok and Rorem, 2014; Elkind, 2007; Kostelnik and Grady, 2009; Wien, 2004).

- Many educators of elementary-grade children aged 6-8 believe that programs for younger children pay inadequate attention to literacy and numeracy or to learning outcomes and K-12 standards. These worries have several sources: concern about children entering elementary school not adequately prepared for academic learning and ready to progress through the next grade levels and perceived differences in perspectives on appropriate learning and instructional practices, including the perception among many that the early childhood field provides passive support for development, rather than active promotion of learning and skill development driven by learning standards and student outcomes. Although these perspectives are changing, there is ongoing debate over the best method for implementing early learning standards into early learning curricula and how to align these standards with K-12 standards. Similar divisions and perceptions exist not just between early childhood education and elementary education, but also between the early and later grades within K-12 systems (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009).

- Debates over adult-led versus child-initiated learning experiences can be contentious. For some in education, a philosophical divide exists about whether early learning experiences are best when mainly child-initiated or when primarily adult-led instruction is used. This can be a contentious issue in which both sides are driven by concerns about the ramifications for children and find it challenging to find common ground (Kostelnik and Grady, 2009). However, although some tend to treat these as mutually exclusive, research findings actually support a mix of these approaches (see the discussion of false dichotomies in instructional approaches in Chapter 6).

Kindergarten Teachers Getting Lost in the Middle

In the context of the differences between preprimary and elementary education, kindergarten teachers often are in the middle, not really part of either group when it comes to communities of practitioners who share a work environment. In many states, even if there is a commitment to making kindergarten, and increasingly prekindergarten, universally available, they are often voluntary rather than part of compulsory education. Whether and how kindergarten and prekindergarten are offered often is left to the discretion of the locality, and they often differ from the rest of the public school system in various ways. In some school systems, for example, kindergarten and prekindergarten are only a half-day. Some programs also

are funded through a different mechanism than the regular public school funding stream. Thus, in some states and districts, the “K-12 system” is in reality a grade 1-12 system, leaving kindergarten teachers outside of the established structure.

Systems Capacity to Improve Continuity in Care and Education for Young Children

Currently, the work of bridging early childhood and early elementary education to increase continuity of care and education for children from birth through age 8 rarely is the purview of a single entity at the local, state, or national level. Typically, one or more agencies oversee early childhood programs for young children before entry into kindergarten, while a public education system oversees K-12 education. (In a few states, such as New Jersey and North Carolina, the departments of education have small “P-3” offices that are charged with promoting greater coordination between early childhood and early elementary initiatives.) While interagency collaboration sometimes occurs, it usually does so in a piecemeal fashion, focusing on one specific topic (e.g., aligning learning standards), rather than taking a more systemic approach. Also, the extent to which agencies serving children from birth through third grade come together often relies on the priorities and interests of the agency leaders and value they place on alignment and coordination. In short, early childhood and public education leaders work largely in separate circles (even if they are in the same agency), and often lack formal, systematic opportunities to ensure that their goals, strategies, and policies are mutually reinforcing and supportive. Given this context, the work required to increase continuity becomes no one’s official job. Local, state, and federal systems lack the organizational leadership to develop comprehensive strategies, manage their execution, and monitor their progress.

In addition, even if both early childhood and K-12 leaders understand the importance of increasing continuity across the 0-8 age span, they may struggle to be able to take this work on. The recent increased attention to both early childhood and K-12 education has resulted in a myriad of reforms in both sectors. The expansion of quality rating and improvement systems, the greater focus on standards and assessments, and the pressure to help the early childhood workforce attain higher education and more training experiences are just a few priorities that early childhood program and policy leaders need to address. In the meantime, K-12 educators and leaders are implementing more rigorous college- and career-ready standards and assessments; revamping their human capital policies, from recruitment to compensation to teacher evaluation; and responding to pressures to improve test scores and other performance metrics. Arguably, there has been

more activity within the early childhood community to assume continuity as a goal, but helping both sectors understand how this work can advance their existing priorities and then finding the capacity (time, staffing, financial resources) to take it on is an important challenge to tackle.

In summary, the ultimate goal for this committee was to contribute to a more coherent care and education continuum for children through the infant-toddler years, preschool ages, and early grades across all settings, including the home, family childcare homes, childcare centers, preschools, and elementary schools, as well as across home visiting, early intervention, and other consultative services and across referrals to and linkages with the health and social services sectors. These different settings and the professionals who work within them are characterized by differences in terminology, expectations, approaches to teaching and learning, accountability policies, relationships with families and the community, funding, and system priorities and pressures. Bringing these multiple different systems together will require coordination and alignment across multiple interconnected moving parts and will entail significant conceptual and logistical challenges for the stakeholders involved: care and education practitioners; leaders, administrators, and supervisors; those who provide professional learning for the care and education workforce; policy makers; health, mental health, and social services providers; and parents and other adults who spend time with young children. The aim of this report is to navigate these challenges by identifying the areas of convergence that can be leveraged to build and sustain a strong foundation for providing high-quality, consistent early learning opportunities for children as they grow.

The committee was tasked with applying what is known about child development and early learning to inform how the early care and education workforce can support children from birth through age 8. This report presents the committee’s findings, conclusions, and recommendations. The report is divided into five parts. After this introductory chapter, Part I continues with Chapter 2, which describes in greater detail the current landscape of care and education for children from birth through age 8.

Part II focuses on the science of child development and early learning in two chapters. Chapter 3 describes interactions between the biology of development, particularly brain development, and the environmental influences experienced by a child. Chapter 4 then summarizes what is known about the various elements of child development and early learning in four domains: cognitive development, general learning competencies, socioemotional development, and health and physical well-being.

Part III turns to the implications of the science for the care and edu-

cation of children from birth through age 8. Chapter 5 draws on the science of child development and early learning, as well as the realities of the landscape described in Chapter 2, to establish the critical need—and the opportunities—for continuity in care and education across the birth through age 8 continuum. Chapter 6 then explores in depth the educational practices that, when applied with consistency and high quality over time for children as they age, can continuously support development and early learning. Chapter 7 considers the knowledge and competencies needed by professionals with responsibilities for the education of young children to implement these practices.

Part IV focuses on the development of the care and education workforce. Chapter 8 presents a framework for considering the key factors that contribute to workforce development and quality professional practice for care and education professionals who work with children from birth through age 8. Chapter 9 covers higher education programs and professional learning during ongoing practice. Chapter 10 considers current qualification requirements for educators who work with young children and systems and processes for evaluating educators, as well as program accreditation and quality improvement systems. Chapter 11 turns to factors that contribute to the work environment and the status and well-being of educators, such as compensation and benefits, staffing structures and career advancement pathways, retention, and health and well-being.

Ultimately in Chapter 12, the committee offers a blueprint for action based on a unifying foundation for the development of a workforce capable of providing more consistent and cumulative support for the development and early learning of children from birth through age 8. This foundation encompasses: essential features of child development and early learning, shared knowledge and competencies for care and education professionals, principles for high-quality professional practice at the level of individuals and the systems that support them, and principles for effective professional learning. This foundation is intended to inform coordinated and coherent changes across systems for individual practitioners, leadership, organizations, policies, and resource allocation. Chapter 12 also provides a framework for the inclusive and collaborative systems transformation that will be needed to carry out these changes. Finally, the committee offers recommendations for specific action in the areas of qualification requirements for professional practice, higher education, professional learning during ongoing practice, evaluation and assessment of professional practice, the role of leadership, interprofessional practice, improvement of the knowledge base, and support for implementation. Accompanying these recommendations is extensive discussion of considerations for their implementation.

Barnett, W. S., D. J. Epstein, A. H. Friedman, J. Stevenson-Boyd, and J. T. Hustedt. 2009. The state of preschool 2008: State preschool yearbook. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research.

Bassok, D., and A. Rorem. 2014. Is kindergarten the new first grade? The changing nature of kindergarten in the age of accountability. Working Paper Series No. 20. Charlottesville: EdPolicyWorks, University of Virginia.

ECS (Education Commission of the States). 2005. Attendance: Compulsory school age requirements. http://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/50/51/5051.htm (accessed March 22, 2015).

Elkind, D. 2007. The power of play: How spontaneous, imaginative activities lead to happier, healthier children. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Lifelong.

K-12 Academics. 2014. Preschool education. http://www.k12academics.com/systems-formaleducation/preschool-education (accessed December 18, 2014).

Kagan, S. L., E. Moore, S. Bredekamp, M. E. Graue, L. M. Laosa, E. L. Boyer, L. F. Newman, L. Shepard, V. Washington, and N. Zill. 1995. Reconsidering children’s early development and learning: Toward common views and vocabulary. Washington, DC: National Education Goals Panel.

Kostelnik, M. J., and M. L. Grady. 2009. Getting it right from the start: The principal’s guide to early childhood education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Snyder, T. D., and S. A. Dillow. 2011. Digest of education statistics 2010. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Wat, A., and C. Gayl. 2009. Beyond the school yard: Pre-K collaborations with community-based partners. Washington, DC: Pew Center on the States.

Wien, C. A. 2004. Negotiating standards in the primary classroom: The teacher’s dilemma. New York: Teachers College Press.

This page intentionally left blank.