Status and Well-Being of the Workforce

This chapter examines a variety of factors that contribute to the work environment, status, and well-being of the professionals who provide care and education for children from birth through age 8, including discussion in the key areas of compensation and benefits, staffing structures and career advancement, retention, and health and well-being. As described in Chapter 8, these factors—many of which are at the institutional or systems level—play important roles in the capacity of these educators for quality professional practice.

The current status of compensation, benefits, and related factors about the work environment for educators are summarized in Table 11-1. The Society for Research in Child Development reported that adequate compensation for teachers as well as opportunities for professional learning, mentoring, and supervision can lead to the development of an effective and strong early childhood workforce (Rhodes and Huston, 2012). However, the recent follow-up report to the 1989 National Child Care Staffing Study found that little progress has been made over the past 25 years in addressing the need for increased supports and compensation for early childhood professionals. Despite advances in the science of child development and knowledge of the impact of care and education professionals on the development of young children, many of these professionals still are receiving low wages. The result is high turnover rates in the field and increased economic instability among staff. Since 1997, compensation for childcare educators has

TABLE 11-1a Overview of Factors That Affect the Status and Well-Being of the Care and Education Workforce

| K-12 Schools | Early Childhood Settings | ||||

| Compensation and Benefits |

Uniform pay scales are established by local public school districts. Employer-offered health and retirement benefits are included in pay packages provided to the vast majority of public school teachers. Payment for vacation, holidays, sick leave, planning, and professional sharing time, is standard. K-12 teachers typically work a 10-month year. 2012 mean annual salaryd:

|

Teaching staff typically are paid by the hour. Pay varies dramatically within and across sectors, and formal pay scales are uncommon.a One-quarter of teachers are estimated to have no health care coverage; those covered may receive insurance through a spouse, public agency, or employer.b Payment for vacation, holidays, sick leave, planning, and professional sharing time is not standard (Whitebook et al., 2009). Teachers are predominantly full-time workers. Teachers in state-funded prekindergarten and Head Start programs typically work a 10-month year, while teachers in most other center-based programs and childcare work a 12-month year.c |

|||

| State-Funded Prekindergarten | Head Start | All Other Center-Based Programs | Home-Based/ Family Childcare | ||

|

2012 mean hourly wages: |

2012 mean hourly wages:

|

2012 mean hourly wages:

|

Median wage for “childcare workers”: $9.38 per hour/$19,510 per year (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014d)g | ||

|

|

||||

a Only 4 states and 1 territory have a salary or wage scale for various professional roles; 37 states and 1 territory provide financial rewards for participation in professional development (e.g., a one-time salary bonus for completing training); 12 states provide sustained financial support on a periodic, predictable basis (e.g., annual wage supplement, based on the highest level of training and education achieved) (NSECE, 2013; Whitebook, 2014).

b Six states and 1 territory offer or facilitate benefits (e.g., health insurance coverage, retirement) for the workforce (NSECE, 2013; Whitebook, 2014).

c In 2012, 74 percent of center-based teachers were full-time workers; the median hours worked per week by early care and education teachers was 39.2 (NSECE, 2013).

d The averages are based on 157,370 kindergarten teachers and 1,360,380 elementary teachers. Comparable annual salary data for early childhood educators by public prekindergarten, Head Start, and childcare are not available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. However, comparable data are available for the more inclusive categories of childcare worker ($21,230) and preschool teacher in public or private programs ($30,750). The Bureau of Labor Statistics is considering new occupational definitions to capture more accurate information about early childhood industries. (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014b).

e While pay is higher for teachers in school-sponsored public prekindergarten, it is important to note that only 6 percent of preschool teachers work in such programs nationally (NSECE, 2013).

f The NSECE is based on more than 10,000 questionnaires.

g Data are for “childcare workers” which include those employed in childcare centers, preschools, public schools, and private homes.

SOURCE: Adapted from Building a Skilled Workforce (prepared for The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) (Whitebook, 2014).

TABLE 11-1b Overview of Factors That Affect the Status and Well-Being of the Care and Education Workforce

| K-12 Schools | Early Childhood Settings | ||

| Work Environment |

The staffing structure typically is a teacher working primarily alone in the classroom; an assistant teacher or paraprofessional may be present in the early grades or to assist children with special needs. Staff cohesion, collaboration, the availability of teacher leadership opportunities, and the quality of school leadership are identified by teachers as factors influencing the quality of the work environment (Tooley, 2013). |

School- or Center-Based | Home-Based/Family Childcare |

|

The staffing structure typically is a teacher working with other teachers or assistants in the classroom because of the greater need of young children for individual attention. Assistant teachers are included in the required ratio of adults to children set by licensing laws determined by each state. Working conditions vary by sector and funding stream, with publicly funded programs typically offering better support (Whitebook et al., 2009). Staff stability and training, staff cohesion, collaboration, the availability of teacher leadership opportunities, and the quality of school/program leadership are identified by teachers as factors influencing the quality of the work environment (Whitebook and Ryan, 2011; Whitebook and Sakai, 2004). |

Depending on program size, a typical teacher may work individually or in teams with other teachers or assistant teachers. The age range of the children may include infants and toddlers and preschool-age children, as well as school-age children before and after school. Family childcare workers typically work in their own home (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014d). Practitioners may work part time and/ or be self-employed. Practitioners also often perform tasks related to running their business (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014d). For example, a 2003 survey of family childcare providers in Massachusetts found that providers spent 52 hours per week working directly with children and an additional 10 hours per week on tasks related to their business (Marshall et al., 2003). |

||

SOURCE: Adapted from Building a Skilled Workforce (prepared for The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) (Whitebook, 2014).

TABLE 11-1c Overview of Factors That Affect the Status and Well-Being of the Care and Education Workforce

| K-12 Schools | Early Childhood Settings | ||||

| Unionization |

Thirty-five states and the District of Columbia have laws guaranteeing collective bargaining rights for K-12 teachers. Teacher unions exist in all 50 states (Whitebook et al., 2009). Working conditions, including benefits, are established through collective bargaining agreements.

|

Union presence is limited and varies by sector. Teachers in school-sponsored preschools and Head Start are the most likely to be members of unions.a Teacher membership in professional organizations is low.b |

|||

| State-Funded Prekindergarten | Head Start | All Other Center-Based Programs | Home-Based/Family Childcare | ||

| Union density: 16.7 percent of 1.5 million preschool and kindergarten teachersd | No current data available | No current data available | Fourteen states allow unions to represent home-based providers (Blank et al., 2010) | ||

a Forthcoming data from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) will include information on union density across early care and education sectors (NSECE, 2011).

b The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), the largest ECE professional organization, has approximately 80,010 members. However, many of its members do not teach children directly but hold such roles as teacher educator or director. Membership has declined in recent years (NAEYC, n.d.-b).

c Union density figures cannot be disaggregated for elementary and middle school teachers (Department for Professional Employees and AFL-CIO, 2013).

d Union density figures cannot be disaggregated for preschool and kindergarten teachers. Because more kindergarten than preschool teachers are employed by public schools, union density among preschool teachers is likely to be much lower than 16.7 percent. Preschool and kindergarten teachers who were union members earned more than twice as much as those who were not. Several unions represent early childhood practitioners, most notably the Service Employees International Union; the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees; the American Federation of Teachers; and the National Education Association (NEA). The NEA allows private preschool workers to seek union membership (Department for Professional Employees and AFL-CIO, 2013).

SOURCE: Adapted from Building a Skilled Workforce (prepared for The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) (Whitebook, 2014).

seen a 1 percent increase, whereas salaries for preschool educators have increased by 15 percent. Childcare educators earn an average of $10.33 per hour, preschool educators earn $15.11, and kindergarten educators earn $25.40, although these numbers vary by setting (Whitebook et al., 2014).

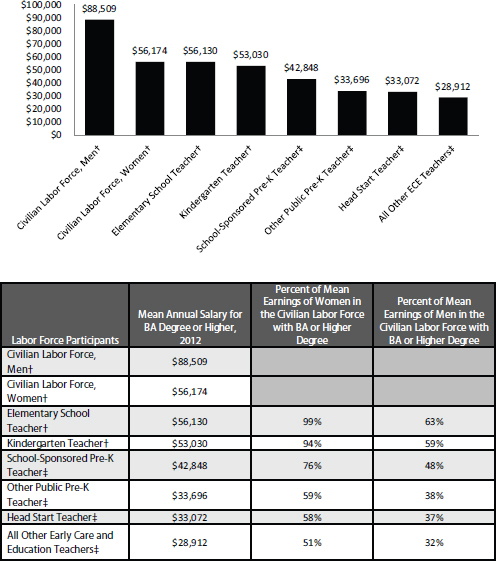

Wages also do not reflect the education and qualifications of the professionals in the field; the mean annual salary for early care and education professionals holding bachelor’s degrees is considerably lower than the salaries earned by professionals with a bachelor’s degree in other fields. For example, the average hourly wages of center-based educators vary with education level, ranging from $9.60 for those with a high school diploma or less to $17.30 for those holding a bachelor’s degree or higher (NSECE, 2013) (see Table 11-2).

Professionals working with children from birth through age 5 earn on average approximately 50 percent of what women in the civilian labor force earn and nearly 32 percent of what men in the civilian labor force earn. Those in school-sponsored prekindergarten are closer to the mean, while kindergarten and elementary school teachers earn salaries nearly equal to the mean for women (see Figure 11-1) (Whitebook et al., 2014).

Additionally, benefits for the early care and education workforce outside school settings are limited for some and unavailable for others. A 2012 study reviewing compensation and benefits for employees in North Carolina early care and education programs found that nearly half of the centers provided either full or partial financial assistance for health care services, and nearly 70 percent of programs provided full or partial assistance for childcare costs. While many programs offered paid holiday and vacation time, only two-thirds provided paid sick leave. In family childcare programs, however, it is less common for early childhood professionals to receive any paid benefits, as programs often are small and run by a single individual (Child Care Services Association, 2013). Home-based providers in Massachusetts, for example, indicated closing their homes for holidays or vacation for a minimum of 5 days per year. The majority of providers took

TABLE 11-2 Mean Hourly Wage of Center-Based Educators

| Highest Degree Received | Mean Hourly Wage of Center-Based Educators |

| High school or less | $9.60 |

| Some college, no degree | $10.50 |

| Associate’s degree | $12.90 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | $17.30 |

| Total | $13.10 |

SOURCE: Adapted from Building a Skilled Workforce (prepared for The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) (Whitebook, 2014).

FIGURE 11-1 Compensation for the care and education workforce.

NOTES:

† The wages are based on 1,360,380 elementary school teachers and 157,370 kindergarten teachers (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014b).

‡ National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team (2013). Number and characteristics of early care and education teachers and caregivers: Initial findings, Table 17 and Appendix Table 11, p. 27.

ECE = early care and education.

SOURCE: Adapted from Building a Skilled Workforce (prepared for The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) (Whitebook, 2014).

no sick leave, and 11 percent had no type of health insurance (Marshall et al., 2003).

Early care and education professionals outside of school settings often have no workplace standards such as paid planning time and a dependable schedule, nor do they have many opportunities for increased compensation based on education and training (Whitebook et al., 2014). Moreover, many of these professionals experience economic insecurity and express concern over having money to cover food, transportation, health care, and housing costs; having their work hours or benefits reduced; having their classes canceled because of low enrollment; or being laid off. Because of their low wages and concern over financial issues, it is common for professionals working in early care and education to participate in public support programs regardless of their educational background (Whitebook et al., 2014). Some also need to pursue a second job to make ends meet (Child Care Services Association, 2013). Program directors have difficulty attracting quality and effective professionals to the field because of the low compensation, minimal benefits, and lack of job security (Child Care Services Association, 2013).

In 2012, the Society for Research in Child Development offered policy recommendations for supporting the financial status of early care and education professionals, including increases in wages and benefits and opportunities for training and professional learning. Other suggestions included pay parity, better working conditions, and trainings to support the mental and emotional well-being of professionals working with young children (Society for Research in Child Development, 2012).

Currently, a number of financial supports are available to those in the care and education workforce. To raise the education levels of those working with young children, the Teacher Education and Compensation Helps (T.E.A.C.H.) scholarship offers early childhood teachers and assistant teachers the opportunity for continued education. More than 80 percent of those who participate do so to ease the financial burden of education costs (Child Care Services Association, 2013). The Child Care WAGE$ program is another opportunity for financial support available to low-paid childcare educators and directors who work with children from birth through age 5 in Florida, Kansas, and North Carolina (NAEYC, n.d.-a). This program provides salary supplements with the aim of lowering turnover rates in childcare programs, as well as creating opportunities for educational growth among early care and education professionals. Benefits of the WAGE$ program include financial stability, increased staff morale in the workplace, and decreased turnover rates. Additional supports that can help alleviate financial stress among early care and education professionals include paid time for training, breaks, and planning (Child Care Services Association, 2013).

Along with financial supports and salary supplements, several states are implementing policies that call for reducing pay discrepancies between professionals working with children in prekindergarten classrooms and public school teachers. Opportunities for pay parity can reduce the financial stress experienced by professionals in the field and attract qualified and effective educators. New Jersey and Oklahoma both have implemented policies on pay parity, and the Alliance for Early Childhood Finance has established a set of policy recommendations for narrowing the wage gap in Louisiana (Bornfreund, 2013; Stoney, 2013; WestEd E3 Institute, 2013).

STAFFING STRUCTURES AND CAREER ADVANCEMENT PATHWAYS

Two key institutional factors that affect quality practice—staffing structures and career options and opportunities for advancement—are closely interrelated. Staffing structures encompass how settings are staffed with tiered professional roles (such as lead educators, assistant educators or aides, master educators, mentors/coaches, and supervisors). Career advancement pathways encompass what professional roles and opportunities for career advancement are available to an individual professional, which include advancing in experience level within a role, such as novice to expert, as well as advancement and promotion to higher-level professional roles. Professional learning systems need to be equipped to prepare care and education professionals to assume the roles that are needed.

Policies on staffing of classrooms and centers determine the types of professional roles needed and the responsibilities of each role, as well as how many positions within those roles are needed in the system. These numbers in turn determine the opportunities for employment and advancement available to individuals. These decisions are sometimes based on a child development perspective, but more often are based on an organizational or financial perspective.

Staffing Structures

Evidence is lacking with which to definitively recommend ideal staffing structures and staffing supports across different settings and age groups. No comparative research has examined how different staffing structures contribute to the learning and development of young children. Staffing also depends on such contextual factors as resources in the setting and the labor market in a given geographic area. Even in the absence of a best-case staffing structure, however, it is important that any process designed to improve professional learning and the quality of professional practice include careful consideration be given to such issues as

- limiting teacher–child ratios and class sizes;

- using a tiered professional structure, for example,

- – director or principal (plus assistant director/principal depending on size),

- – lead educator in each classroom who is responsible for the learning environment and for curriculum implementation, including individualized instructional strategies,

- – assistant educators,

- – availability of some kind of coach or mentor (either a more experienced colleague, a designated coach role, or from an external source), and

- – support staff that either provide services from other sectors (e.g., health and mental health, family support services) or help with referrals or navigating other systems with which care and education teachers may not be familiar;

- supervisory support that provides both oversight/accountability and supportive/reflective supervision;

- everyday practical support (e.g., supplies, learning environment); and

- consultant and referral supports (designated staff, as well as resources and tools) for screening/identification and linking to additional services.

Career Advancement Pathways

Many states or localities are describing pathways for career development to help with retention and recruitment of good educators. A common challenge in both cases is how to make these pathways reflective of increasing competency, as opposed to increasing education. This is happening for both early childhood and elementary school settings, although for somewhat different reasons. Elementary school efforts are more about identifying educators who have demonstrated greater competency among their peers and/or have taken leadership roles within their schools or districts. Early childhood efforts are focused mainly on professionalizing the field and pointing a path toward more knowledge and skills, starting from a relatively low level. A recent scan of statewide “career lattices”1 found that 37 states have some form of documentation describing how an early childhood professional might acquire more training, education, and competencies to support career advancement (Missouri Coordinating Board for Early Childhood, 2014). In many cases, the term “career” was used broadly

_____________

1 The terms used vary greatly, including “lattice,” “ladder,” “steps,” “tiers,” “spectrum,” and “pathway.”

to mean training/education/etc. that one might obtain to advance in one’s career, rather than to refer to a direct link to job eligibility. These pathways shared a number of common features, such as formal education, college credits, training hours, membership in a professional organization, meeting licensure requirements or obtaining a certificate or credential.

The current status of recruitment and retention for educators is summarized in Table 11-3. Just as early care and education professionals have seen no significant changes in wages over the past 25 years, there has been very little change in turnover rates, which have remained at 14 to 15 percent since 2002. Nearly one-third of professionals who have left the field have done so because of inadequate compensation (Whitebook et al., 2014). A 2003 study on job turnover (leaving the job) and occupational turnover (leaving the field) among childcare center educators and directors found that childcare centers had the highest turnover rate in the care and education field. Data show that the average turnover rate in childcare settings is more than four times higher than that in elementary schools. High turnover rates can lower the quality of childcare and education programs, as frequent staff changes can have negative effects on children’s development—particularly for infants and toddlers, whose attachments and relationships with educators are disrupted (Rhodes and Huston, 2012). Indeed, continual changes and instability in caregivers can cause a child to demonstrate aggressive behaviors and become socially withdrawn.

Educators and directors report leaving their jobs or the field because of concerns and pressures involving low pay, job instability, and changes in staff or leadership. Highly qualified staff are drawn to and tend to continue their employment in centers that exhibit stability among their teaching and leadership staff and offer salaries that exceed the median wage. High-quality centers are often those that offer higher salaries (Whitebook and Sakai, 2003). However, it is difficult for childcare centers to retain highly trained educators with bachelor’s degrees as they may also be qualified to teach in elementary schools or other settings that, as mentioned earlier, offer better salaries and benefits and greater stability (Whitebook and Sakai, 2003). Approaches to minimizing job turnover rates in this field include increasing wages and benefits for educators, directors, and administrative staff, as well as implementing quality policies regarding hiring practices and the work environment (Whitebook and Sakai, 2003). Conversely, it is worth noting that job turnover can be perceived as positive when ineffective educators leave the field (NRC and IOM, 2012).

TABLE 11-3a Overview of Factors That Affect the Status and Well-Being of the Care and Education Workforce

| K-12 Schools | Early Childhood Settings | |||

| Recruitment |

Estimated replacement rates (2012-2022) for elementary school teachers are 22 percent.a Employment of elementary school teachers is projected to grow by 12 percent from 2012 to 2022.b Estimated replacement rates (2012-2022) for elementary and secondary principals is 26.6 percent (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014a). Employment of elementary and secondary principals are projected to grow by 6 percent from 2012 to 2022 (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014c). Recruitment pressures are higher among schools considered difficult to staff (typically those in low-income, high-poverty communities, and often staffed by novice teachers). |

Estimated replacement rates (2012-2022) are 28.1 percent for preschool teachers and 29.4 percent for childcare workers.c Employment is projected to grow by 17 percent for preschool teachers and 14 percent for childcare workers from 2012 to 2022 (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014b,c). Estimated replacement rates (2010-2022) for preschool and childcare administrators is 26.6 percent (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014a). Employment of preschool and childcare administrators is projected to grow by 17 percent from 2012 to 2022 (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014b,c). |

||

| State-Funded Prekindergarten | Head Start | All Other Center-Based Programs | ||

|

|

|

||

a “Replacement rates” refers to the estimated job openings resulting from the flow of workers out of an occupation. This includes separations due to retirements as well as other reasons for departure. Estimates reflect decreases in job demand in an occupation, but not potential expansion (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014a).

b Projected growth refers to the projected increase in demand for workers during a specified period. The growth rate for overall employment in the United States is estimated at 10.8 percent for 2012 to 2022 (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014c).

c In most occupations, separations occur mainly among workers over 40; occupations with relatively low entrance requirements and compensation (as is typical of many early care and education jobs) typically have large net separations among young workers (Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor, 2014a).

SOURCE: Adapted from Building a Skilled Workforce (prepared for The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) (Whitebook, 2014).

TABLE 11-3b Overview of Factors That Affect the Status and Well-Being of the Care and Education Workforce

| K-12 Schools | Early Childhood Settings | |

| Turnover/Retention/Dismissal |

Teachers in unions typically have job protection once they have achieved tenure; dismissal follows collective bargaining protocol. Increasingly, states are mandating consideration of more stringent measures of teacher performance in awarding tenure and determining layoffs.a

Teachers leave their jobs for a variety of reasons: 24.9 percent seek a different occupation; 13.7 identify pregnancy or family issues; 22.4 percent retire; 25.1 percent identify dissatisfaction with administration or lack of support on the job; and 13.9 percent list other reasons.b Compensation influences turnover, but work environment plays a significant role (Glazerman et al., 2013). In 2008-2009, 14.6 percent of elementary school teachers left teaching; 6.4 percent changed schools. 22.9 percent of all teachers (K-12) with 1-3 years’ experience left teaching; 6.5 percent changed schools (Institute of Education Sciences and National Center for Education Statistics, 2008-2009b). |

Job turnover is high primarily because of low wages (Ryan and Whitebook, 2012).

Dismissal is at the discretion of the program administrator in accordance with state and federal employment law, unless collective bargaining protocol is in place. High rates of job turnover are associated with low program quality, inability of programs to improve and sustain improvements, and negative outcomes for children. Frequent staff changes create challenges in building essential cohesive classroom teaching teams (Whitebook and Sakai, 2003). Many teachers who leave their jobs remain in the occupation but move to other early care and education sectors that pay higher salaries.c A study in Massachusetts found that 25 percent of family childcare providers intended to quit within the next 3 years, and another 25 percent intended to quit within the next 9 years; another quarter expected to stay in their positions for the next 15 years. One-quarter of family care providers noted that upon leaving their positions, they would pursue work or school in another field (Marshall et al., 2003). No current national data are available for turnover for educators in early childhood settings.d |

a In 2014, for example, 16 states required the results of teacher performance evaluations for tenure decisions, compared with 10 states in 2011 (Fensterwald, 2014; Thomsen, 2014).

b In 2007-2008, there was a total of 347,000 leavers (Institute of Education Sciences and National Center for Education Statistics, 2008-2009a).

c Movement from one job to another in the field explains the relatively long occupational tenure for early care and education teachers (NSECE, 2013). In a 2011 study of early childhood teachers in North Carolina, 81 percent of teachers identified higher pay as the most important motivator for their remaining in the field (Child Care Services Association, 2012).

d Forthcoming data from the NSECE will provide information on turnover; Center-based Provider Questionnaire (published November 28, 2011) (NSECE, 2011).

SOURCE: Adapted from Building a Skilled Workforce (prepared for The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) (Whitebook, 2014).

The health and well-being of care and education professionals play a critical role in their effectiveness as educators and thus in the development of children. The socioemotional competence of educators can influence student behavior and the classroom environment (Klassen et al., 2012). At the same time that socioemotional well-being is so important for the quality of their professional practice, however, care and education professionals experience higher rates of stress than those in many other fields, and this is a primary reason why many people leave the field (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2013). Teachers experience a number of sources of stress in their daily routine (Montgomery and Rupp, 2005). This stress can lead to emotional exhaustion, physical illness, burnout, and loss of interest in the teaching field (Klassen et al., 2012; Richards, 2012). Depression and other mental health conditions also are not uncommon among early childhood professionals. Sixteen percent of family care providers and approximately 30 percent of center-based staff and directors have depressive symptoms, and this rate is highest for professionals working with children in low-income households (Whitebook and Sakai, 2004). These effects of the stressors they experience can restrict the ability of educators to create positive, high-quality learning environments for their students (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2013).

Professionals who are socially and emotionally competent are self-aware and can identify how to engage and motivate their students (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). Those who have a feeling of connectedness or relatedness with their students often find greater enjoyment in their daily work, which leads to a strong commitment to their job. They also experience less anxiety, anger, and burnout (Klassen et al., 2012). Executive function abilities such as working memory, inhibition of immediate reactions or impulses, and rapid shift in focus may help educators maintain control in the classroom and appropriately handle students’ behavioral issues by moderating their response to these stressors. Establishing a positive classroom environment, moreover, helps educators achieve their teaching goals (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2013).

For some educators the effort to support individual children with specific behavioral issues exceeds their available emotional resources, which can increase their stress levels. The bidirectional relationship between children’s behavioral problems and educators’ experience of job stress can lead to a cycle of heightened negative interactions between students and educators (Friedman-Krauss et al., 2013).

An additional source of stress is uncertainty in the education profession. Care and education professionals react differently to this uncertainty: some become anxious and frustrated and feel that that they are falling

short of the standards they are expected to meet, while others feel that the evolving expectations of what defines good teaching can help them improve upon their teaching practice (Helsing, 2003). Helsing (2003) describes how uncertainty in teaching can lead to routinized lessons, predictability, and boredom, and suggests that leaders can work toward minimizing uncertainty by identifying key elements of good teaching and reinforcing the need for collaboration and reflective practice.

A survey of Head Start programs in Pennsylvania offers a glimpse into how working conditions affect the physical and mental health of Head Start professionals. Head Start employs nearly 200,000 staff, including teachers, managers, and home visitors, in stressful working conditions, primarily with children who exhibit poor self-regulation. This survey looked at the mental and physical health of 2,200 staff in 66 Head Start and Early Head Start programs. The staff surveyed had a high rate of physical issues, including back pain, headaches, obesity, asthma, hypertension, and diabetes. The primary mental health issue was depression, with depressive symptoms being experienced by 25 percent of those surveyed. Additionally, a large percentage of staff frequently felt ill or missed work, which has been shown to disrupt healthy development of children in these programs (Whitaker et al., 2013).

There are several approaches to promoting educators’ mental and emotional wellness. These approaches include trainings that promote emotional awareness, socioemotional competence, stress reduction, and reflective practices (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). Some programs also offer retreats that support healthy personal development by focusing on establishing relationships with colleagues and students, as well as workshops that promote stress reduction techniques (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). While educators are unable to change the contexts in which they teach and the levels of stress they experience, they can improve their management of stress by improving their coping strategies. These strategies include maintaining a positive attitude and sense of humor; turning to family and social supports; finding time for relaxation, reflection, hobbies, and exercise; and getting adequate sleep (Richards, 2012). Additionally, some schools provide mindfulness training for educators, which has been reported to reduce stress levels and depression, as well as increase awareness and self-regulation (Flook et al., 2013; Gold et al., 2010). Mindfulness in educators also is linked to better health and functioning in the classroom, which can affect student outcomes (Flook et al., 2013; Gold et al., 2010; NAEYC, n.d.-a; Stoney, 2013; WestEd E3 Institute, 2013; Whitaker et al., 2014).

Perspectives from the Field

“I don’t think we have the right supports in place to increase quality practice. People aren’t getting paid enough. The professionals carry the brunt of the underfunding of the system and are trying to do their best without sufficient resources.”

————————

See Appendix C for additional highlights from interviews.

Conclusions About the Status and Well-Being of the Workforce

The early care and education workforce is at risk financially, emotionally, and physically, subject to a vicious cycle of inadequate resources, low qualification expectations, low education levels, and low wages that is difficult to break. Appropriate income, resources, support, and opportunities for career development are essential for bringing excellent candidates into the workforce, retaining them as they further develop their knowledge and skills, and ensuring that they advance their knowledge and skills through professional learning opportunities.

The early childhood workforce in settings outside of elementary schools is particularly affected by a quality/cost mismatch in the care and education market. Childcare costs are highly driven by personnel and worker turnover is high. Federal subsidies often are inadequate to pay for the high quality of care they are intended to promote, and most families are unable to pay for the quality of care they desire.

Blank, H., N. D. Campbell, and J. Entmacher. 2010. Getting organized: Unionizing home-based child care providers, 2010 update. Washington, DC: National Women’s Law Center.

Bornfreund, L. A. 2013. An ocean of unknowns: Risks and opportunities in using student achievement data to evaluate preK-3rd grade teachers. Washington, DC: New America Foundation.

Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Department of Labor. 2014a. Employment projections: Replacement needs. http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_table_110.htm (accessed January 12, 2015).

———. 2014b. Occupational employment and wages news release. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ocwage.htm (accessed January 12, 2015).

———. 2014c. Occupational outlook handbook. http://www.bls.gov/ooh (accessed January 12, 2015).

———. 2014d. Occupational outlook handbook: Childcare workers. http://www.bls.gov/ooh/personal-care-and-service/childcare-workers.htm (accessed July 7, 2014).

Child Care Services Association. 2012. Working in early care and education in North Carolina: 2011 workforce study. Chapel Hill, NC: Child Care Services Association.

———. 2013. Working in early care and education in North Carolina: 2012 workforce study. Chapel Hill, NC: Child Care Services Association.

Department for Professional Employees and AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations). 2013. Teachers: Preschool through postsecondary. http://dpeaflcio.org/professionals/professionals-in-the-workplace/teachers-and-college-professors (accessed January 9, 2015).

Exstrom, M. 2012. Teaching in charter schools. Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislatures.

Fensterwald, J. 2014. Judge strikes down all 5 teacher protection laws in Vergara lawsuit. EdSource. http://edsource.org/2014/judge-strikes-down-all-5-teacher-protection-laws-invergara-lawsuit/63023#.VLVUEivF-Sp (accessed January 13, 2015).

Flook, L., S. B. Goldberg, L. Pinger, K. Bonus, and R. J. Davidson. 2013. Mindfulness for teachers: A pilot study to assess effects on stress, burnout, and teaching efficacy. Mind, Brain, and Education 7(3):182-195.

Friedman-Krauss, A. H., C. C. Raver, J. M. Neuspiel, and J. Kinsel. 2013. Child behavior problems, teacher executive functions, and teacher stress in Head Start classrooms. Early Education and Development 1-22.

Glazerman, S., A. Protik, B. Teh, J. Bruch, and J. Max. 2013. Transfer incentives for high performing teachers: Final results from a multisite experiment. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Gold, E., A. Smith, I. Hopper, D. Herne, G. Tansey, and C. Hulland. 2010. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) for primary school teachers. Journal of Child and Family Studies 19(2):184-189.

Helsing, D. 2003. Regarding uncertainty in teachers and teaching: Learning to love the questions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, Graduate School of Education.

Institute of Education Sciences and National Center for Education Statistics. 2008-2009a. Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS): Number and percentage of public and private school teacher leavers who rated various factors as very important or extremely important in their decision to leave their 2007-08 base year school, by selected teacher and school characteristics in the base year: 2008-09. http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/tables/tfs0809_027_f12n.asp (accessed January 13, 2015).

———. 2008-2009b. Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS): Percentage distribution of private school teachers by stayer, mover, and leaver status for selected teacher and school characteristics in the base year: 1994-95, 2000-01, 2004-05, and 2008-09. http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/tables/tfs0809_022_cf2n.asp (accessed January 13, 2015).

Jennings, P. A., and M. T. Greenberg. 2009. The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research 79(1):491-525.

Klassen, R. M., N. E. Perry, and A. C. Frenzel. 2012. Teachers’ relatedness with students: An underemphasized component of teachers’ basic psychological needs. Journal of Educational Psychology 104(1):150-165.

Marshall, N. L., C. L. Creps, N. R. Burstein, K. E. Cahill, W. W. Robeson, S. Y. Wang, J. Schimmenti, and F. B. Glantz. 2003. Family child care today: A report of the findings of the Massachusetts Cost/Quality Study: Family child care homes. Wellesley, MA: Wellesley Centers for Women and Abt Associates, Inc.

Missouri Coordinating Board for Early Childhood. 2014. “Career lattice” paper: Early childhood state charts describing steps for advancement. Jefferson City: Missouri Coordinating Board for Early Childhood.

Montgomery, C., and A. A. Rupp. 2005. A meta-analysis for exploring the diverse causes and effects of stress in teachers. Canadian Journal of Education 28:458-486.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). n.d.-a. Critical facts about the early childhood workforce. http://www.naeyc.org/policy/advocacy/ECWorkforceFacts#WAGE (accessed March 22, 2015).

———. n.d.-b. Membership. http://www.naeyc.org/membership (accessed January 12, 2015).

NCES (National Center for Education Statistics). 2008. Average salaries for full-time teachers in public and private elementary and secondary schools, by selected characteristics. http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d09/tables/dt09_075.asp (accessed January 12, 2015).

NRC (National Research Council) and IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2012. The early childhood care and education workforce: Challenges and opportunities: A workshop report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NSECE (National Survey of Early Care and Education). 2011. Workforce [classroom staff] questionnaire. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation; Administration for Children and Families; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

———. 2013. Number and characteristics of early care education (ECE) teachers and caregivers: Initial findings from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE). Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation; Administration for Children and Families; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Rhodes, H. H., and A. C. Huston. 2012. Building the workforce our youngest children deserve. Social policy report. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for Research in Child Development.

Richards, J. 2012. Teacher stress and coping strategies: A national snapshot. The Educational Forum 76(3):299-316.

Ryan, S., and M. Whitebook. 2012. More than teachers: The early care and education workforce. In Handbook of early childhood education, edited by R. C. Pianta. New York: Guilford Press. p. 98.

Society for Research in Child Development. 2012. Strengthening the early childhood care and education workforce would benefit young children. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for Research in Child Development.

Stoney, L. 2013. Early care education compensation: Policy options for Louisiana. West Palm Beach, FL: Alliance for Early Childhood Finance.

Thomsen, J. 2014. Teacher performance plays growing role in employment decisions. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States.

Tooley, M. 2013. Is money enough to keep more high-quality teachers in high-need schools? http://www.edcentral.org/is-money-enough-to-keep-more-high-quality-teachers-in-highneed-schools/#sthash.hTWyRIVF.dpuf (accessed January 12, 2015).

WestEd E3 Institute. 2013. Early childhood credentials and systems for professional preparation: Comparative data from 5 states (Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma). http://www.ctc.ca.gov/educator-prep/early-care-files/2014-01-ECE-summary.pdf (accessed January 5, 2015).

Whitaker, R. C., B. D. Becker, A. N. Herman, and R. A. Gooze. 2013. The physical and mental health of Head Start staff: The Pennsylvania Head Start Staff Wellness Survey, 2012. Preventing Chronic Disease 10:E181.

Whitaker, R. C., T. Dearth-Wesley, R. A. Gooze, B. D. Becker, K. C. Gallagher, and B. S. McEwen. 2014. Adverse childhood experiences, dispositional mindfulness, and adult health. Preventive Medicine 67:147-153.

Whitebook, M. 2013a. Preschool teaching at a crossroads. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

———. 2013b. Staffing a universal preschool program will be no small task. EdSource, http://edsource.org/2013/staffing-a-universal-preschool-program-will-be-no-small-task/30091#.VLVDUivF-Sp (accessed January 13, 2015).

———. 2014. Building a skilled teacher workforce: Shared and divergent challenges in early care and education and in grades K-12. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute for Reseach on Labor and Employment.

Whitebook, M., and S. Ryan. 2011. Degrees in context: Asking the right questions about preparing skilled and effective teachers of young children: Preschool policy brief. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University, National Institute for Early Education Research.

Whitebook, M., and L. Sakai. 2003. Turnover begets turnover: An examination of jobs and occupational instability among child care center staff. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 18(3):273-293.

———. 2004. By a thread: How child care centers hold on to teachers, how teachers build lasting careers. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Whitebook, M., D. Gomby, D. Bellm, L. Sakai, and F. Kipnis. 2009. Preparing teachers of young children: The current state of knowledge, and a blueprint for the future. Executive summary. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment.

Whitebook, M., C. Howes, and D. Phillips. 2014. Worthy work, still unlivable wages: The early childhood workforce 25 years after the national child care staffing study. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

This page intentionally left blank.