11

Effective Mental Health Care

An effective health care system, as defined by the Institute of Medicine, is one that provides “services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refrains from providing services to those not likely to benefit” (IOM, 2001, p. 39). The use of evidence-based care to treat mental health problems has been shown to be associated with symptom reduction and reduced morbidity and mortality among patients. Conversely, the consequences of inadequate care for people with mental health conditions are well known and include an increased risk of disability and impairment, adverse health behaviors, poor health outcomes, and higher health system costs (Collins et al., 2010; Harpaz-Rotem and Rosenheck, 2011; Kessler et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2005).

To answer the question of whether the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides evidence-based mental health treatments to veterans, this chapter examines the availability of evidence-based practices in the VA system, the quality of mental health providers, and the provision of mental health care to veterans. The section dealing with that third issue examines whether veterans are receiving adequate treatment, the factors associated with receiving treatment, and patient engagement in care. Provider adherence to treatment protocols (fidelity of treatment) and patient outcomes, including satisfaction with care, are also discussed. Supporting evidence for these discussions comes from the committee’s review of the literature, its survey and site visit research, and information gathered from the VA.

AVAILABILITY OF EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES FOR MENTAL HEALTH IN THE DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS

Medical interventions should rest on sound conceptual and empirical foundations and be rigorously designed and evaluated. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the practice that results from the integration of the best available research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values (IOM, 2001). Over the past decade, the VA has placed a high priority on making EBPs more widely available to veterans who need mental health services. Below, the committee describes the VA’s activities to increase its capacity

to provide evidence-based psychotherapy and then provides a summary of providers’ and veterans’ perspectives on mental health treatment availability.

See Chapter 4 for details about the EBPs (including psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments) recommended in various VA and Department of Defense (DoD) clinical practice guidelines for the management of veterans seeking VA care for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, substance use disorder, or who exhibit a high-risk for suicide.

Evidence-Based Psychotherapy and Pharmocotherapy

Psychotherapy

For more than a decade, the VA has been executing a multipronged approach to increase the availability of evidence-based treatments for veterans who seek mental health care. Table 11-1 shows the details of the VA’s approach to disseminating and implementing evidence-based psychotherapy throughout the health system. Beyond what is outlined in Table 11-1, there are other elements that should be considered when delivering evidence-based treatments. The Chronic Care Model (The MacColl Center, 2017), for example, outlines some of the components needed to effectively implement evidence-based treatments. Studies on effective dissemination strategies show that using multifaceted strategies, as the VA has, is the most effective way to change provider behavior (BootsMiller et al., 2004; Ruzek and Rosen, 2009).

Provider training is a major focus of the VA’s EBP initiative and has been key to improving the VA’s capacity to provide psychotherapy to veterans. Details about the training program are presented in Chapter 8 in the provider quality section. Some specific VA policies supporting the implementation of evidence-based care include requiring all facilities to have staff trained in evidence-based psychotherapy treatment, designating local EBP coordinators, and instituting new policy standards. Regarding the latter, the VA released the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Handbook 1160.01: Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics (the VHA Uniform Mental Health Services Handbook) (VA, 2015), which set minimum standards for providing mental health services and evidence-based treatments across VA facilities.

Pharmocotherapy

The VA’s progress in the use of evidence-based practices includes expanding the implementation of evidence-prescribing practices to ensure that veterans have access to high-quality, evidence-based pharmacological treatments for mental health. In 2013 the VA launched the Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI), a system-wide psychopharmacology quality improvement (QI) program to support high-quality prescribing practices at Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) and facilities. PDSI provides quarterly scores on 35 prescribing performance metrics, offers tools to identify actionable opportunities for patient care improvement, and supports QI implementation through educational resources, such as a virtual learning collaborative, training, and technical assistance. The VA reports that phase 1 of PDSI (ended in the fourth quarter of fiscal year [FY] 2015) had increased the use of evidence-based pharmacological treatments for veterans with substance use disorders, decreased inappropriate use of benzodiazepines, decreased polypharmacy, and decreased the use of potentially harmful medications in veterans with PTSD. Preliminary results from phase 2 (set to end in the third quarter of FY 2017), which has focused on improving evidence-based prescribing among older veterans, has also led to improvements in care. Fewer older veterans are receiving potentially harmful benzodiazepines and anticholinergic medications.

| Implementation Level | Focus | Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Policy | National requirements for EBP availability |

|

| Provider | Staff training and support |

|

| Local systems | Local clinical infrastructures and buy-in |

|

| Patient | Clinical implementation strategies |

|

| Accountability | Monitoring and evaluating implementation and impact |

|

NOTES: EBP = evidence-based psychotherapy (in this table only; elsewhere EBP = evidence-based practice).

SOURCE: Karlin and Cross, 2014.

With the growing epidemic of opioid misuse and opioid use disorder in the United States, including among the nation’s veterans, the VA has deployed the Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) requirements to all VISNs with the aim of ensuring that opioids are used in a safe, effective, and judicious manner. The implementation of OSI is similar to that of PDSI, described above, including the use of performance measures and educational activities. As part of the OSI, the VA launched the Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution program. In addition to OSI, the VA is implementing a new clinical practice guideline to evaluate, treat, and manage patients with chronic pain who are on or being considered for long-term opioid therapy. The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain, Version 3.0—2017 is based on evidence reviewed through December 2016 and replaces the 2010 VA/DoD guideline for opioid therapy (Opioid Therapy Chronic Pain Work Group, 2017).

Provider and Veteran Perspectives on Availability of Care

From the site visit interviews with VA providers, the committee found that across all 21 sites, VA clinicians indicated that they had been trained in and were using a variety of evidence-based treatments for mental health. The principles of the various modalities are used either in individual therapy or in group sessions. Some staff reported that providing time-limited services with an evidence base has helped to keep the patients “flowing” through the system, with the recommended frequency of visits and within the guidelines recommended.

The committee’s survey asks about the availability of a range of VA mental health services from the veterans’ perspective. Among VA users who have mental health need, a majority were very or somewhat satisfied with the availability of general mental health services (62 percent) and with the availability of medication management for mental health (56 percent). On the other hand, fewer VA users reported being very or somewhat satisfied with the availability of specialized mental health services (40 percent), psychotherapy (39 percent), case management (31 percent), emergency services (25 percent), and group therapy (21 percent). These results are presented in more detail in Chapter 6, Table 6-18, under the heading Barriers and Facilitators to Service Use.

DELIVERY OF MENTAL HEALTH CARE IN THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION

Despite the availability of effective treatments, millions of Americans who might benefit from treatment are not seeking treatment or are not receiving adequate treatment. Studies show that gaps in the use of effective treatments exist in both general health care and mental health care and in both the civilian and veteran health systems (Cook and Wiltsey-Stirman, 2015; Farmer et al., 2016; Harpaz-Rotem and Rosenheck, 2011; Watkins et al., 2015). However, research indicates that the mental health treatment gap is smaller in the VA than in the private sector (Watkins et al., 2015). While studies comparing the quality of mental health care received by veteran and by civilian populations are scarce, there are data showing that the VA performs favorably on key measures of mental health quality when compared to private health plans. In an analysis of use data for VA patients and for patients enrolled in private health plans, Watkins et al. (2015) compared veterans who had received a mental health diagnosis (i.e., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, PTSD, major depression, or substance use disorder) in FY 2007 (N = 836,519) to a comparable population in private plans (N = 545,484) on seven measures related to medication evaluation and management.1 The gap in providing the indicated care between the VA and private sector was at least 10 percentage points. Veterans with schizophrenia or major depression were more than twice as likely to receive appropriate initial medication treatment, and veterans with depression were more than twice as likely to receive appropriate long-term treatment. Nonetheless, on four of the seven measures, fewer than half of the veterans who were eligible to receive the indicated medication-related treatment received it.

Until recently, there was no systematic method for measuring how widely evidence-based psychotherapy was used throughout the VA; the VA did not have a standard method of collecting data on how many and which patients who had PTSD received cognitive processing therapy (CPT) or prolonged exposure (PE) therapy, for example (IOM, 2014). The VA has reported to this committee that after several years of testing and development, it has begun fully implementing progress note templates in the

___________________

1 The measures addressed medication laboratory tests, any laboratory screening tests, antipsychotics, 12-week supply, maintenance treatment with antipsychotics, maintenance treatment with mood stabilizers, antidepressants, 12-week supply, and maintenance treatment with antidepressants.

electronic medical record in order to document and track the system-wide delivery of evidence-based psychotherapy (Rosen et al., 2016; VA, 2017).

The VA’s new electronic progress note templates allow clinicians to document individual sessions of specific evidence-based psychotherapies. Prior to this time, the only available data were medical billing codes describing the length of sessions and whether a session was an individual or group format, rather than describing the type of psychotherapy delivered. The new clinical progress templates collect data about patient characteristics, symptoms, treatment setting, the therapy process, the number of sessions, and treatment completion (Karlin and Cross, 2014; Rosen et al., 2016). Used appropriately—provider compliance with data entry is key—these templates are expected to significantly enhance the VA’s capacity to systematically evaluate the use of psychotherapy treatment throughout the system of care. Until then, such evaluation relies on the examination of research studies conducted with veteran populations.

Research on the VA’s delivery of evidence-based psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy treatments focuses on three aspects of care: treatment initiation, adherence, and completion; patient engagement in treatment; and treatment fidelity. Many of the studies examined the rates of veterans receiving treatment. The actual services delivered were measured against practice standards related to the frequency and length of visits, the medication dosage and supply, follow-up and monitoring, or the length of the treatment course (Cook and Wiltsey-Stirman, 2015; Cook et al., 2014; Cully et al., 2008). In these evaluations, the common treatment standards used were the VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines (refer to Chapter 4), the facilities standards mandated by the VHA Uniform Mental Health Services Handbook (VA, 2015), and HEDIS®2 quality measures. It can be concluded that care is inadequate if large numbers of veterans do not appear to be treated with an EBP or when the level of treatment received does not meet the practice standards for what is considered a full dose or full course of treatment. Cook and Wiltsey-Stirman (2015) stressed that the majority of studies are descriptive and that there is a need for more rigorous, experimental studies of treatment implementation.

Below, the key findings from the committee review of the literature are summarized and organized by three aspects of care: treatment initiation, adherence, and completion; patient engagement in treatment; and treatment fidelity.

Treatment Initiation, Adherence, and Completion

Millions of Americans experience mental health disorders, but only a subset of these individuals actually receives services. The 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicates that an estimated 35.2 percent of 10.4 million adults with a serious mental illness (SMI) had not received mental health services in the past. SMI was defined as any mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder—excluding substance use disorders and developmental disorders—that substantially interfered with or limited one or more major life activities. Of the 19.9 million adults needing substance use treatment, less than 11 percent (2.1 million) received specialty treatment (Park-Lee et al., 2017). Harpaz-Rotem and Rosenheck (2011) reported on studies that found that a significant proportion of patients entered treatment but did not receive the minimum number of sessions needed to achieve clinical benefits; an estimated 20 to 57 percent of patients dropped out after the first session of mental health treatment.

Similarly, several studies of the VA found that a large proportion of veterans do not receive any treatment following a diagnosis of PTSD, alcohol or other substance use disorder (SUD), or depression. With respect to EBPs, studies from the early years of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts (2001–2005) (Cully et al., 2010; Garfield et al., 2011; Hunt and Rosenheck, 2011; Rosen et al., 2011) as well as more

___________________

2 HEDIS® is a registered trademark of the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

current studies (Rosen et al., 2016) consistently show that the implementation of EBPs at the VA is variable and quite low at some sites.

Summarized below are findings from studies the committee reviewed that assess the degree to which patients are receiving evidence-based care as well as factors associated with initiation and retention in treatment.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Spoont et al. (2014) found that 45 percent of veterans did not receive any PTSD treatment (either psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy) within 6 months of a PTSD diagnosis. Another study showed that 29 percent of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans with PTSD received minimally adequate treatment within 1 year of their diagnosis (Lu et al., 2011). In a relatively small study (N = 137), Harpaz-Rotem et al. (2014) found that 73 percent who screened positive for PTSD or depression initiated care in the year following their mental health assessment. However, only 45 percent of those who initiated care (33 percent of the total sample) received adequate care (attended 12 or more visits within 1 year of their assessment). Data from VA specialty PTSD clinics in New England showed that only 6 percent of veterans with a new PTSD diagnosis received at least one session of evidence-based psychotherapy within their first 6 months of treatment (Watts et al., 2014). CPT use ranged from 1 to 13 percent, and PE therapy varied from 0 to 3 percent across six sites in the study. Kehle-Forbes et al. (2015) found higher rates of EBT use, but still only half of the veterans who were referred for PE therapy or CPT in the study sample completed the treatment.

Among veterans who do receive treatment for PTSD, many do not receive guideline-concordant care. In a large study (N = 356,958) of veterans with PTSD receiving medication from V providers, Abrams et al. (2013) found that just over 65 percent of veterans were prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and 37 percent were prescribed benzodiazepines, which are not guideline-recommended treatments for PTSD and which can interfere with EBTs for PTSD. Similarly, Jain et al. (2012) found that 14 percent of veterans with a recent PTSD diagnosis and without a clear comorbid psychiatric diagnosis were prescribed benzodiazepines.

Alexander et al. (2015) also found evidence of treatment patterns that were not consistent with the VA guidelines for PTSD. Among the 12,844 VA patients who were prescribed prazosin for PTSD in 2010, less than 40 percent were still taking the drug 1 year later, and fewer than 20 percent received the minimum recommended dosage according to VA guidelines (although the reasons for the discontinuation were not clear). Looking specifically at adherence to treatment and the relapse of veterans discharged from an inpatient PTSD program who were prescribed antidepressants (N = 82), Lockwood et al. (2009) found overall adherence to be 34 percent, with no significant association between adherence and rehospitalization. Notably, given the fact that there were only 82 subjects in the study, this result might be based on a low-power analysis.

Substance Use Disorder

Similar shortfalls have been reported for SUD treatment. Among veterans aged 21 to 34 in the general population, Golub et al. (2013) found that only 10 percent of non-institutionalized veterans who screened positive for SUD had received treatment in the previous year, and 16 percent of veterans overall had an unmet need for SUD treatment. Hawkins et al. (2010) also found patterns of care not consistent with VA guidelines in a cross-sectional national sample of VA outpatients randomly selected for standardized medical record review (N = 12,092). According to VA guidelines, all veterans who screen positive for

alcohol misuse are supposed to receive a brief intervention, but only 32 percent of men who screened positive for alcohol misuse (AUDIT-C ≥5) received advice or feedback (the more inclusive measure of brief intervention), and only 12 percent received advice and feedback (the performance measure for brief intervention for FY 2008). About half of the veterans (49 percent) who screened positive for alcohol misuse received either a brief intervention or a referral to treatment, although only 13 percent of positive-screening veterans actually scheduled appointments. These findings were similar to those of Grossbard et al. (2013), who found that among 4,725 OEF/OIF VA outpatients with alcohol screening (2006–2010), 61 percent of veterans with positive alcohol misuse screens received either a referral or a brief intervention. Watkins and Pincus (2011) reported that 71 percent of veterans had documentation of a brief intervention, current specialty care, or a completed referral to specialty mental health care during FY 2007.

Among veterans with documented alcohol dependence, pharmacotherapy was offered or contraindicated for only 16.4 percent within 30 days of a new treatment episode, and 21.5 percent received psychotherapy with documentation of relapse prevention therapy (Watkins and Pincus, 2011). However, Del Re et al. (2013) suggest that VA data may be underestimating the rates of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder by as much as 40 percent because topiramate (which is not Food and Drug Administration approved for alcohol dependence) is commonly used off label in the VA to treat alcohol dependence but is not captured in the monitoring data.

An investigation into opioid addiction treatment and opioid prescribing practices also revealed patterns not consistent with VA guidelines. Watkins and Pincus (2011) found that only 25 percent of veterans with opioid addiction had documentation that maintenance therapy had been offered or contraindicated within 30 days of new treatment in FY 2007. The VA Clinical Practice Guidelines for SUD (VA and DoD, 2009) state that “addiction-focused pharmacotherapy should be considered, available, and offered if indicated for all patients with opioid dependence and/or alcohol dependence.” Another study of 4,270 veterans who were 18 to 30 years of age and treated at VA Palo Alto Health Care System found that only 31 percent of veterans receiving prescription opioids underwent drug testing while on the drugs (Wu et al., 2010); however, the guidelines recommend random testing of all recipients (VA, 2010).

Major Depression

Using the HEDIS® quality measures, Pfeiffer et al. (2011) found patterns of inadequate care for veterans with major depressive disorder. Among a large sample of veterans discharged from a psychiatric inpatient stay with a major depressive disorder diagnosis (N = 45,587), less than 40 percent completed a follow-up visit within 7 days of discharge and just over 75 percent did within 30 days. Less than 60 percent of the veterans received adequate antidepressant coverage following discharge (at least 72 of 90 days), and less than 13 percent received adequate psychotherapy (at least 8 encounters). In another look at adherence, Zivin et al. (2009) found antidepressant medication adherence to be low (<0.8 medication possession ratio3) for about half of veterans 3 months following discharge from an inpatient psychiatric stay. At 6 months following discharge, 60 percent of veterans had low adherence. The Government Accountability Office (GAO, 2014) (2014) also found treatment patterns that were not consistent with VA guidelines for major depressive disorder. In a review of 30 veterans’ medical records only 6 (20 percent) were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item (PHQ-9) at the start of antidepressant treatment, and only 4 (13 percent) were reassessed 4 to 6 weeks following treatment

___________________

3 Medication possession ratio is defined as the total number of days’ supply received divided by the number of days’ supply needed for continuous use.

initiation. Only 18 veterans (60 percent) received a PHQ-9 assessment at any encounter during their course of treatment. The GAO concluded that the VA does not have mechanisms in place that fully assess the extent to which care is consistent with the guideline, and it recommended that the VA “implement processes to review data on veterans with MDD [major depressive disorder] prescribed antidepressants to evaluate the level of risk of any deviations from recommended care and remedy those that could impede veterans’ recovery” (GAO, 2014, p. 37).

Factors Associated with Receiving Any, Adequate, or Complete Treatment

Several studies have found older age (>30 years) to be associated with staying in treatment for PTSD, SUD, depression, or some combination (Erbes et al., 2009; Kehle-Forbes et al., 2015; Tate et al., 2011), although being over 65 was also associated with less than adequate care (Pfeiffer et al., 2011). Erbes et al. (2009) showed that OEF/OIF veterans had significantly lower rates of session attendance and higher rates of treatment dropout than (older) Vietnam veterans, even after controlling for differences in the treatment presentation. Other factors that have been found to predict treatment initiation, retention, or greater concordance with guidelines include being white, being female, living less than 30 miles from a facility, having a recent major health event, having three or more medical comorbidities, having greater PTSD symptom severity, having depressive symptoms, having more severe alcohol use disorder comorbid with traumatic brain injury and PTSD, and having low social support (Grossbard et al., 2013; Harpaz-Rotem et al., 2014; Morgan et al., 2012; Pfeiffer et al., 2011; Zivin et al., 2009).

Individual Perceptions and Treatment-Seeking

As the committee had found in its analysis of the veteran survey data presented in Chapter 6, individual perceptions of the VA and mental health care in general may determine whether an individual veteran seeks the mental health care he or she may need. While in some cases perceptions do not reflect the structural or policy realities at the VA, to a veteran in need of care, his or her perceptions are major factors that drive the decision to seek care or not. It is important to note, however, that addressing common perceptions requires a different approach than addressing other barriers to care, particularly when the perception does not align with the reality. For example, if the common perception is that a local VA health facility is not capable of providing services to women veterans with military sexual trauma, but that facility has recently established a women’s clinic, it is critical not only to address the barrier by establishing the clinic, but also to address the perception of gaps in care separately.

The committee reviewed several studies in the literature that examined how personal perceptions of mental health care affect mental health treatment behavior among veterans. Not surprisingly, veterans who perceive a need for mental health care are more likely to seek treatment. The committee’s survey of veterans found that among OEF/OIF/Operation New Dawn veterans who perceived that they needed mental health care and who screened positive for a mental health condition, 55 percent had sought mental health care services (see Chapter 6). Similarly, veterans with positive perceptions of psychotherapy and antidepressants are more likely to seek those treatments than veterans who do not view them positively, although the association is modest (Spoont et al., 2014). A prospective study of veterans with PTSD or depressive symptoms found that veterans who perceived barriers, including access-related barriers (“I can’t take time off work”; “It is difficult to schedule an appointment”), stigma-related barriers (“It would harm my career”), and trust-related barriers (“My visit would not remain confidential”) were no less likely to actually receive care than veterans who did not report these barriers (Hoerster et al., 2012). Similarly, Harpaz-Rotem et al. (2014) found that perceived barriers to care and negative beliefs about

mental health care (“I don’t trust mental health professionals”; “Psychotherapy is not effective for most people”; and “Mental health care does not work”) did not affect mental health care retention, although the sample was limited to veterans who had at least received their initial mental health assessment at the VA.

Other research looks at the relationship between reported barriers and treatment-seeking behavior. In a qualitative study of 143 veterans, Stecker et al. (2013) looked at the reasons why OEF/OIF veterans who screened positive for PTSD did not initiate PTSD treatment. Participants cited four major reasons for not seeking treatment: (1) concerns about treatment (for example, “I don’t want medication”) (40 percent); (2) emotional readiness (for example, “It’s too hard to talk to someone”) (35 percent); (3) stigma (for example, “I will get into trouble if I go to treatment”) (16 percent); and (4) logistical issues (for example, “I don’t have time”) (8 percent). Ouimette et al. (2011) also looked at this issue and found that discomfort with seeking help and concerns about social consequences were the primary reasons veterans with recent PTSD diagnoses did not seek care. Concerns about the skill and sensitivity of VA staff, logistical barriers, and concerns about fitting in were also reported, but were less concerning on average. Notably, being an OEF/OIF veteran was associated with being more likely to have a perception of not fitting in. Individuals with more severe PTSD symptoms, particularly those with avoidance symptoms, reported greater barriers to care than those with less severe symptoms.

Drapalski et al. (2008) studied perceived barriers to mental health treatment among veterans with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. Sixty-seven percent of the study’s participants (N = 136) reported having experienced at least one barrier to receiving mental health care. Personal factors (for example, personal crisis, inability to explain needs, not knowing how to make an appointment, and forgetting an appointment) were the most commonly cited barriers (56 percent of respondents). Time constraints (24 percent) and transportation (24 percent) were the second-most reported barriers to mental health care. Institutional constraints (such as “it took too long to get care” or “was not given an appointment”) were the next most reported barriers to mental health care (21 percent). In general, participants with more severe psychiatric symptoms reported more barriers (Drapalski et al., 2008).

Patient Engagement and Retention in Treatment

Many factors at the patient, provider, and system levels determine whether people who are experiencing mental health problems get the care they need. Engaging people in mental treatment can be challenging because of the nature of the condition itself and because of health, social, and economic consequences that act as barriers to care (Collins et al., 2010; Harpaz-Rotem and Rosenheck, 2011). In the veteran population, military culture, personal experiences in the military, and perceptions about the VA system may also play a large role in decisions whether to seek treatment and remain engaged.

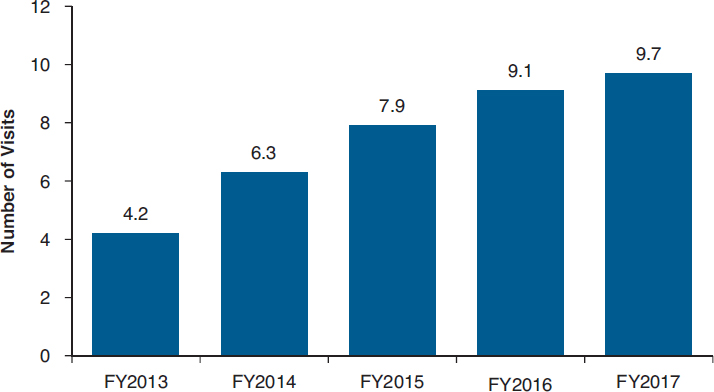

In Chapter 10, a description of VA patient-centered mental health care includes evolving VA strategies to increase engagement and retention in care, such as expanding the peer support program and launching a new online decision-support tool for PTSD treatments (VA, 2017).4 In response to the committee’s inquiry about how retention in treatment has changed over the past few years (VA, 2017), the VA reported that concurrent with its heavy investment in hiring additional mental health providers and training providers in evidence-based psychotherapy over the last 5 years, there has been an increase in the average number of mental health visits completed by veterans within a given 12-month period (see Figure 11-1).

In a look at various research studies, Harpaz-Rotem and Rosenheck (2011) found that among OEF/OIF and Vietnam veterans with a new PTSD diagnosis, the retention and number of mental health

___________________

SOURCE: VA, 2017.

visits were lower among OEF/OIF veterans. However, this finding was primarily a function of age and comorbidity rather than of service era (Harpaz-Rotem and Rosenheck, 2011). In another study, OEF/OIF veterans with more severe PTSD symptoms (specifically, re-experiencing symptoms) and greater support from their military unit were found to be more likely to initiate care following their initial mental health assessment, and those with numbing symptoms were found to be more likely to stick with treatment. Personal stigma and positive opinions of care were not associated with either initiation or retention (Harpaz-Rotem et al., 2014).

Tate et al. (2011) compared the predictors of retention among veterans with SUD and co-occurring depression participating in one of two treatment interventions. Participants were assigned to either a cognitive behavioral therapy-based treatment or a 12-step program. Both interventions were 24 weeks, and retention did not differ between the two. Similar to the Harpaz-Rotem and Rosenheck study cited above, being older and Caucasian was found to be predictive of retention. Marital status, education, neuropsychological functioning, financial stress, chronic health problems, treatment motivation, and psychiatric severity were not predictive of retention. In a study of retention in opioid agonist therapy, the dosage was the greatest predictor of retention, with those receiving 59 milligrams or more of methadone per day more likely to stay in therapy. And among those receiving that dosage, higher satisfaction was a predictor of retention. Ethnicity and employment status were not predictors of retention (Villafranca et al., 2006).

Efforts to improve engagement can be effective. Smelson et al. (2012) evaluated an intervention designed to improve engagement among veterans with co-occurring mental disorders (schizophrenia or bipolar) and SUD. Participants were assigned to either a time-limited care (TLC) coordination intervention (which provides the same case manager across inpatient and outpatient settings who delivers brief integrated mental health and substance abuse care) or to a matched attention (MA) health education control intervention. Participants assigned to the TLC intervention were more engaged—69 percent attended outpatient appointments within 14 days of discharge versus only 33 percent of veterans assigned to the MA control. TLC participants were twice as likely as MA participants to be engaged with outpatient services at the end of the intervention period (44 versus 22 percent; p < 0.01).

Similarly, Schaefer et al. (2011) looked at how continuity-of-care efforts at the VA result in differences in engagement among veterans in inpatient and outpatient SUD treatment programs. Overall, veterans who participated in programs that provided more continuity of care services stayed in treatment longer. Interestingly, when continuity of care was lacking, veterans with moderate-to-low psychiatric severity were less engaged in treatment than high-severity veterans. The moderate-to-low psychiatric severity veterans were, however, more engaged than high psychiatric severity veterans when the continuity of care services was high. This suggests that veterans with moderate to low psychiatric severity were more responsive to engagement efforts than veterans with high psychiatric severity. Veterans with more severe psychiatric problems at entry and a history of SUD or psychiatric visits stayed in care longer, and engagement was the strongest predictor of abstinence for them. Lash et al. (2007) also found that continuing care efforts were effective at improving patient engagement and abstinence among veterans with SUD.

Treatment Alliance

The presence of treatment alliance, which includes a patient–therapist agreement on the tasks and goals of treatment as well as the bond between patient and therapist, is a well-documented contributor to the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic treatment (Fluckiger et al., 2012). Multiple meta-analyses have found a modest (r = 0.275) but robust effect of therapeutic alliance on psychotherapy outcomes regardless of the theoretical orientation or the treatment technique (Horvath et al., 2011). Although its value in psychopharmacologic treatment is less studied, existing evidence indicates that treatment alliance is also a significant factor in the effectiveness of that approach to treating for mental health conditions (Zilcha-Mano et al., 2015). In addition to the beneficial effects for the patient of experiencing a supportive treatment relationship, treatment alliance can improve outcomes by increasing patient engagement and retention in treatment and enhancing medication adherence. This may be especially true for treatments that are effective but that cause increased distress, such as prolonged exposure therapy, where supportive engagement with a therapist can moderate this distress and help retain patients in treatment.

Survey results (see Chapter 8, Tables 8-4 through 8-7) relating to patients’ satisfaction with their relationships with treatment providers as well as findings from the site visits suggest that VA users generally experience positive treatment relationships with their providers. However, it was apparent from some site visit data that factors external to the treatment relationship (for example, frustrations with parking, limitations on the frequency of treatment sessions, frequent provider changes) may be impinging on treatment alliance and thus negatively affecting the outcomes of care.

Committee’s Research About Perceptions of Treatment Engagement

Mental health clinicians interviewed during multiple site visits expressed concerns about the effect that system barriers (such as long waits for treatment appointments) have on treatment retention and the ability to deliver certain psychotherapeutic interventions with fidelity, that is, according to the schedule indicated by validated treatment protocols (the next section further examines the issue of treatment fidelity). Providers expressed concern about veterans not completing treatment, and staff at some facilities were beginning to consider what they might do to improve retention rates, such as anticipating factors that would contribute to dropout and offering more motivational interviewing in advance.

In some site visit interviews, veterans spoke about their experiences with various treatment interventions, particularly PE therapy and CPT for PTSD, both of which are evidenced-based psychotherapies. By design, both PE therapy and CPT are intense because they require the patient to relive the traumatic

event repeatedly until the memory of the event ceases to carry a negative emotional valence. Several veterans who had attempted a course of either PE therapy or CPT reported feeling overwhelmed after their sessions, and these feelings led them to terminate treatment prematurely. For example, a veteran who was treated for PTSD at the VA described his experience as feeling like an unfinished surgical procedure:

One of them [therapist] goes straight for the PTSD. You start getting all these emotions and feelings and stuff about what’s going on in the past. Then—the next thing you know—the hour’s up—time to go home. They won’t close you back up. Then you go out the rest of your day with anxiety and stuff like that and dealing with your own thing. [Palo Alto, California]

Further exploration of the interview data suggests that the access issues—where patients may be seen only every 30 days (or longer) for psychotherapy—may seriously compromise fidelity to the PE and CPT models, for which treatments should be scheduled 1 week or less apart. One veteran described how agonizing he imagined it would be to continue with PE sessions at 30-day intervals.

Certainly not every veteran interviewed reported such lag times between appointments, but the high dropout rates suggest that long follow-up intervals may be contributing to the problem.

Treatment Fidelity

Fidelity of treatment is the delivery of treatments according to validated treatment protocols. Studies show that variability exists in VA provider adherence to EBPs for mental health (Finley et al., 2015; Rosen et al., 2016). For example, in a survey of providers (N = 128) within VA PTSD clinical teams, 68.8 percent (N = 88) reported that they typically adhered “very often” to the PE manual, and 52.3 percent (N = 67) reported adhering very often to the CPT manual (Finley et al., 2015). Research findings indicate that providers who believe that PE and CPT are effective, especially relative to other treatments, are more likely to use these EBPs and adhere to the treatment manuals. A supportive work environment is another factor associated with whether providers use an EBP (Finley et al., 2015; Rosen et al., 2016).

In the site visit interviews, VA clinical staff reported implementing evidence-based treatments “with flexibility” in an effort to retain veterans in therapy. For example, a VA clinician explained that he will “back off” of trauma work:

I’ve had people come in and say, “That’s it—I can’t do this anymore.” Usually I just say, “How about we sit down and talk about something else for a while?” I haven’t had too many people that had stopped treatment I felt should still be in treatment. [Altoona, Pennsylvania]

Another clinician reported that he will provide extra support to keep veterans in treatment:

[When] things seem worse before they’re better, they [veterans] think, “Well, therapy’s not working for me,” and they terminate treatment . . . and so we try to figure out, “Okay, what can we do in the interim?” [San Diego, California]

Some VA programs had standardized alternative treatments for veterans with PTSD for whom CPT or PE seemed inappropriate at the time of intake. One clinic in Tampa had two separate tracks of PTSD treatment: the first track provided PE or CPT in either individual or group format, and the other focused on anger management and motivational enhancement. Patients in the second track had “psychosis or impulse control problems” or were not motivated: “We have a lot of patients that may not be ready, but everyone around them is like, ‘You need to provide care to them.’” Similarly, a program in San Diego, California, reported that one of the two providers who treated PTSD was

. . . doing more skill-based stabilization, more support-oriented work, until they’re [veterans] ready for an EBT . . . but we’re not terribly rigid about it. When we step out of it [an EBT], it’s thoughtfully.

Overall, many VA clinicians reported that they needed to alter evidence-based therapies or risk the patient dropping out. Across the 21 sites, interview data indicate a good faith effort to implement the evidence-based treatments that are specified in VA Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics (VA, 2015). However, as mentioned earlier with respect to PE and CPT, scheduling challenges can compromise fidelity to the therapy model and contribute to premature dropout:

When they got the first appointment, it was OK. Then when they go to reschedule, “Well, I’ll see you in 60 days.” To me, that’s a huge gap because you lose a lot of the veterans in that process. [VA clinician – East Orange, New Jersey]

I’m at a point of where I need to be seeing people once a week. I might see them every 3 weeks for these evidence-based treatments. That’s not great. [VA clinician – Charleston, South Carolina]

With the VA to be honest, because they can’t see me as often as I need to be seen or give me more individualized care, I feel it’s better to go outside. [Veteran – San Diego, California]

VA clinicians often create variations on the EBTs in an effort to maintain patient engagement.

In other research, Cook et al. (2014) conducted interviews with providers at 38 VA PTSD residential programs and found similar evidence of treatment adaptations to CPT and PE, including tailoring the language or materials, changing the length of the protocols, and integrating with other psychotherapeutic interventions, most of whose effectiveness has not been evaluated.

Little information is available on the flexibility of EBPs, such as CPT or PE, or on how they can be adapted and yet remain effective (Rosen et al., 2016). Preliminary assessments of the effectiveness of adaptations in treatment protocols include studies by Chard et al. (2010), Galovski et al. (2012), Nacasch et al. (2015), and Smith et al. (2015). In addition, more research is needed to assess the effectiveness of different strategies that can help improve fidelity and clinician effectiveness (Rosen et al., 2016). For example, one study found that clinics were more likely to use CPT or PE if clinicians reported previous experience with the treatments, had sustained contact with treatment implementation facilitators/consultants, and received customized training (Watts et al., 2014).

Alterations in treatment protocols based on treatment response, patient preference, or the need to address comorbid conditions are consistent with evidence-based practice. Evidence on psychotherapies that are effective for PTSD indicates that the therapy may be customized as long as the five core components (narration, cognitive restructuring, in vivo exposure, relaxation, and psychoeducation) are applied (Hoge, 2011). However, reducing the frequency of sessions for PTSD treatment may diminish the effectiveness of treatment. Gutner et al. (2016) found that, for women receiving either CPT or PE, less frequent treatment sessions were associated with significantly smaller reduction in PTSD symptoms.

In another study, Lapham et al. (2012) found that the dissemination of a clinical reminder along with a brief intervention for alcohol misuse was associated with increased adoption of brief intervention for veterans who screened positive for alcohol misuse. The prevalence of the brief intervention increased from 42 to 58 percent, indicating that clinical reminders may work to increase the use of interventions.

Patient Outcomes

Ongoing monitoring of patient care is essential to managing treatment delivery and assessing the effectiveness of care. Measuring the results of treatment that patients experience—patient health outcomes—is vital to the advancement of health care quality (IOM, 2001). As mentioned in Chapter 15, a

critical gap in quality measurement is mental health outcome data. As mentioned above, the VA recently started collecting data on the delivery of evidence-based psychotherapy using electronic clinical progress templates incorporated into veterans’ health records (Karlin and Cross, 2014; Rosen et al., 2016; VA, 2017). In the clinical progress templates, providers can document a patient’s symptom changes over the course of treatment. These data are useful for studies examining the impact of treatment on health status and other patient outcomes.

In addition, the VA has a goal for 2016–2018 to complete the development of and to release phase I of the Mental Health Quality and Clinical Outcomes Reporting System, a comprehensive tracking system that will allow providers to track the flow of their patients through mental health care and monitor their outcomes with standardized patient-reported outcome measures (VA, 2016).

Provider Perspectives on Assessing Outcomes

Clinicians told the site visit team about the methods they use to track how their patients do in individual therapy. Generally this consists of administering a self-report scale to the patient at various points during his or her treatment in order to track progress. The most common instruments mentioned by administrators and providers were the PTSD Checklist–Military (PCL-M) and the PHQ-9. However, most programs that asked clinicians to track clinical outcomes were unable to aggregate the outcome data.

More generally, providers gauged the success of individual treatments by qualitatively assessing both the severity of symptoms and the social and occupational functioning of patients. For example, a clinician from East Orange, New Jersey, said that she knows that someone is getting better when, “[t] heir relationships are more stable and more fulfilling—more connected. I know that’s not necessarily quantifiable.” Clinicians reported that they also look for a decrease in symptoms.

I measure by how they’re doing. Are they able to go back to school? Are they able to hold down a job? Do they report a decrease in their hallucinations, a decrease in their paranoia? How [are] they relating to me? [Jesse Brown – Chicago, Illinois]

The committee notes that the qualitative assessments of patient improvements noted by clinicians are not systematic or documented in a uniform way.

Positive Outcomes Reported by Veterans

Veterans who had positive treatment experiences described “getting better” in ways that mirrored their therapists’ assessments. First, psychotherapy helped them learn to identify triggers and proactively manage symptoms. One veteran in Charleston, South Carolina, gave an extended metaphor that described how he identified his triggers: “If I’m going down a road, I used to hit a pothole and I would be stuck in it. Now I can see it coming. I can steer around it, or if I do go down into it, I can figure out how to get out a lot faster with different coping skills.” Another veteran in El Paso, Texas, explained being able to identify his flashbacks to attenuate their impact: “The very few times that I do have flashbacks, I can talk myself out of them because I realize what’s going on. The nightmares—I can wake up and calm myself down.” Another gave a specific example of a trigger and how therapy helped change his reaction: “Helicopters for me are big triggers. They used to fly out by where I lived. They still do now, but I know I am not in Iraq when a helicopter flies over. It’s a big change.” [Biloxi, Mississippi]

Second, veterans felt that their psychotherapy assisted them in engaging in fuller social participation; that is, they were able to leave the house and tolerate public spaces. Being less isolated in turn

permitted them to become more involved with their children. For example, a veteran explained that he knew he was getting better because

I’m more of a benefit toward my daughter than I was before. I’m trying to be a daddy and take her to the park and take her swimming instead of hiding from the world. [Cleveland, Ohio]

A second veteran at a different site echoed that experience:

You’re able to go in a public place with a group of people . . . you’re able to spend time with your kids. . . . Those are the good days. A lot of the time, I’d rather be in bed 16, 17 hours a day in a dark house. If I’m able to leave my house, that’s a better day. [Palo Alto, California]

Veterans said that coping with their symptoms—particularly symptoms of PTSD—was an ongoing task. Said one veteran

Like past trauma events, addiction—those types of things—they don’t go away. It’s in your brain. It’s something that has to be continually worked on. [Palo Alto, California]

Another veteran explained,

At the end of that [therapy] I told myself, “Oh, you’re recovered.” Which is not the case. I have gone back . . . to address other PTSD symptoms that weren’t addressed in the very first round of treatment. [Charleston, South Carolina]

These findings suggest that veterans who received timely treatment through a modality they were able to tolerate reported improvements in functioning and a reduction in avoidance symptoms. Psychotherapy taught veterans how to identify and manage the symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety. At the same time, veterans felt that healing was an ongoing process that might require additional treatment.

Positive outcomes reported in site visit interviews are echoed in our survey results in which 63 percent of survey respondents who used VA mental services indicated that their VA mental health providers helped them either some or a lot, and 65 percent reported that they found the effect of care on their quality of life at least a little helpful. Additional details regarding veteran perspectives on outcomes of care are reported in Chapter 10, Table 10-1.

SUMMARY

Using information from the committee’s site visits and literature research, this chapter examined the availability of evidence-based practices in the VA system, the quality of mental health providers, and the provision of mental health care to veterans. A summary of the committee’s findings on this topic is outlined below.

- Evidence-based mental health services are available to veterans and are mostly concordant with policy mandates.

- The VA uses systematic and tested dissemination strategies to increase provider knowledge and the use of EBPs in the treatment of veteran mental health problems throughout the health system.

- Despite their availability, the implementation of psychotherapies and their fidelity to EBPs, especially for PTSD, is low; many veterans diagnosed with PTSD, depression, and SUD do not receive the recommended treatments.

- Comparative data show that the VA outperforms the private sector on seven process-based quality measures assessing medication treatment for mental health disorders, suggesting that the VA health system provides better care in these areas than does the private sector.

- Nonetheless, large percentages of veterans are not getting care as set forth in clinical standards for dosage, frequency, and follow-up.

- Based on site visits and the research literature, the committee concluded that system issues, such as lag times between appointments that interfere with treatment fidelity (for example, PE and CPT), and patient factors, such as patient preferences for the treatment type, engagement, and retention in treatment, influence the delivery of EBPs.

- Fidelity to EBPs is often lacking; for example, appointments are spaced too far apart, some veterans do not feel ready for EBPs, and some drop out before completing treatment.

- Veterans often reported during the site visits that alternatives to EBPs were not readily available or known to them.

- Some veterans believed that treatment was provided in a “cookbook” fashion with inadequate individualized care.

- Clinicians reported using assessment instruments (for example, the PCL-M and the PHQ for depression) to monitor individual health status, but systematic clinical outcomes data are not collected for many mental health conditions, and data on functional outcomes are not systematically collected from veterans at all.

- The VA recently implemented a clinical progress template in the medical record to advance efforts to systematically assess treatment delivery, treatment fidelity, and patient outcomes.

REFERENCES

Abrams, T. E., B. C. Lund, N. C. Bernardy, and M. J. Friedman. 2013. Aligning clinical practice to PTSD treatment guidelines: Medication prescribing by provider type. Psychiatric Services 64(2):142–148.

Alexander, B., B. C. Lund, N. C. Bernardy, M. L. Christopher, and M. J. Friedman. 2015. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: A potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 76(5):e639–e644.

BootsMiller, B. J., J. W. Yankey, S. D. Flach, M. M. Ward, T. E. Vaughn, K. F. Welke, and B. N. Doebbeling. 2004. Classifying the effectiveness of Veterans Affairs guideline implementation approaches. American Journal of Medical Quality 19(6):248–254.

Chard, K. M., J. A. Schumm, G. P. Owens, and S. M. Cottingham. 2010. A comparison of OEF and OIF veterans and Vietnam veterans receiving cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Trauma Stress 23(1):25–32.

Collins, C., D. L. Hewson, R. Munger, and T. Wade. 2010. Evolving models of behavioral health integration in primary care. New York: Milbank Memorial Fund.

Cook, J. M., and S. Wiltsey-Stirman. 2015. Implementation of evidence-based treatment for PTSD. PTSD Research Quarterly 26(4):1–3. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/newsletters/research-quarterly/V26N4.pdf (accessed October 7, 2017).

Cook, J. M., S. Dinnen, R. Thompson, V. Simiola, and P. P. Schnurr. 2014. Changes in implementation of two evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD in VA residential treatment programs: A national investigation. Journal of Traumatic Stress 27(2):137–143.

Cully, J. A., M. Zimmer, M. M. Khan, and L. A. Petersen. 2008. Quality of depression care and its impact on health service use and mortality among veterans. Psychiatric Services 59(12):1399–1405.

Cully, J. A., J. P. Jameson, L. L. Phillips, M. E. Kunik, and J. C. Fortney. 2010. Use of psychotherapy by rural and urban veterans. Journal of Rural Health 26(3):225–233.

Del Re, A. C., A. J. Gordon, A. Lembke, and A. H. Harris. 2013. Prescription of topiramate to treat alcohol use disorders in the Veterans Health Administration. Addict Science & Clinical Practice 8(1):12.

Drapalski, A. L., J. Milford, R. W. Goldberg, C. H. Brown, and L. B. Dixon. 2008. Perceived barriers to medical care and mental health care among veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 59(8):921–924.

Erbes, C. R., K. T. Curry, and J. Leskela. 2009. Treatment presentation and adherence of Iraq/Afghanistan era veterans in outpatient care for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Services 6(3):175–183.

Farmer, M. M., L. V. Rubenstein, C. D. Sherbourne, A. Huynh, K. Chu, C. A. Lam, J. J. Fickel, M. L. Lee, M. E. Metzger, L. Verchinina, E. P. Post, and E. F. Chaney. 2016. Depression quality of care: Measuring quality over time using VA electronic medical record data. Journal of General Internal Medicine 31(Suppl 1):36–45.

Finley, E. P., H. A. Garcia, N. S. Ketchum, D. D. McGeary, C. A. McGeary, S. W. Stirman, and A. L. Peterson. 2015. Utilization of evidence-based psychotherapies in Veterans Affairs posttraumatic stress disorder outpatient clinics. Psychological Services 12(1):73–82.

Fluckiger, C., A. C. Del Re, B. E. Wampold, D. Symonds, and A. O. Horvath. 2012. How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology 59(1):10–17.

Galovski, T. E., L. M. Blain, J. M. Mott, L. Elwood, and T. Houle. 2012. Manualized therapy for PTSD: Flexing the structure of cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80(6):968–981.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2014. VA health care: Improvements needed in monitoring antidepressant use for major depressive disorder and in increasing accuracy of suicide data. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

Garfield, L. D., J. F. Scherrer, T. Chrusciel, D. Nurutdinova, P. J. Lustman, Q. Fu, and T. E. Burroughs. 2011. Factors associated with receipt of adequate antidepressant pharmacotherapy by VA patients with recurrent depression. Psychiatric Services 62(4):381–388.

Golub, A., P. Vazan, A. S. Bennett, and H. J. Liberty. 2013. Unmet need for treatment of substance use disorders and serious psychological distress among veterans: A nationwide analysis using the NSDUH. Military Medicine 178(1):107–114.

Grossbard, J. R., E. J. Hawkins, G. T. Lapham, E. C. Williams, A. D. Rubinsky, T. L. Simpson, K. H. Seal, D. R. Kivlahan, and K. A. Bradley. 2013. Follow-up care for alcohol misuse among OEF/OIF veterans with and without alcohol use disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 45(5):409–415.

Gutner, C. A., M. K. Suvak, D. M. Sloan, and P. A. Resick. 2016. Does timing matter? Examining the impact of session timing on outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 84(12):1108–1115.

Harpaz-Rotem, I., and R. A. Rosenheck. 2011. Serving those who served: Retention of newly returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan in mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services 62(1):22–27.

Harpaz-Rotem, I., R. A. Rosenheck, R. H. Pietrzak, and S. M. Southwick. 2014. Determinants of prospective engagement in mental health treatment among symptomatic Iraq/Afghanistan veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 202(2):97–104.

Hawkins, E. J., G. T. Lapham, D. R. Kivlahan, and K. A. Bradley. 2010. Recognition and management of alcohol misuse in OEF/OIF and other veterans in the VA: A cross-sectional study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence 109(1–3):147–153.

Hoerster, K. D., C. A. Malte, Z. E. Imel, Z. Ahmad, S. C. Hunt, and M. Jakupcak. 2012. Association of perceived barriers with prospective use of VA mental health care among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Psychiatric Services 63(4):380–382.

Hoge, C. W. 2011. Interventions for war-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Meeting veterans where they are. JAMA 306(5):549–551.

Horvath, A. O., A. C. Del Re, C. Fluckiger, and D. Symonds. 2011. Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy (Chicago) 48(1):9–16.

Hunt, M. G., and R. A. Rosenheck. 2011. Psychotherapy in mental health clinics of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of Clinical Psychology 67(6):561–573.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2014. Treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military and veteran populations: Final assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jain, S., M. A. Greenbaum, and C. Rosen. 2012. Concordance between psychotropic prescribing for veterans with PTSD and clinical practice guidelines. Psychiatric Services 63(2):154–160.

Karlin, B. E., and G. Cross. 2014. From the laboratory to the therapy room: National dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. American Psychologist 69(1):19–33.

Kehle-Forbes, S. M., L. A. Meis, M. R. Spoont, and M. A. Polusny. 2015. Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychological Trauma 8(1):107–114.

Kessler, R. C., P. A. Berglund, M. L. Bruce, J. R. Koch, E. M. Laska, P. Leaf, R. Manderscheid, R. A. Rosenheck, E. E. Walters, and P. S. Wang. 2001. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research 36(6 Pt 1):987–1007.

Lapham, G. T., C. E. Achtmeyer, E. C. Williams, E. J. Hawkins, D. R. Kivlahan, and K. A. Bradley. 2012. Increased documented brief alcohol interventions with a performance measure and electronic decision support. Medical Care 50(2):179–187.

Lash, S. J., R. S. Stephens, J. L. Burden, S. C. Grambow, J. M. DeMarce, M. E. Jones, B. E. Lozano, A. S. Jeffreys, S. A. Fearer, and R. D. Horner. 2007. Contracting, prompting, and reinforcing substance use disorder continuing care: A randomized clinical trial. Psychology of Addictice Behaviors 21(3):387–397.

Lockwood, A., D. T. Steinke, and S. R. Botts. 2009. Medication adherence and its effect on relapse among patients discharged from a Veterans Affairs posttraumatic stress disorder treatment program. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 43(7–8):1227–1232.

Lu, M. W., J. P. Duckart, J. P. O’Malley, and S. K. Dobscha. 2011. Correlates of utilization of PTSD specialty treatment among recently diagnosed veterans at the VA. Psychiatric Services 62(8):943–949.

The MacColl Center. 2017. Improving chronic illness care. http://www.improvingchroniccare.org (accessed October 4, 2017).

Morgan, M., A. Lockwood, D. Steinke, R. Schleenbaker, and S. Botts. 2012. Pharmacotherapy regimens among patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury. Psychiatric Services 63(2):182–185.

Nacasch, N., J. D. Huppert, Y. J. Su, Y. Kivity, Y. Dinshtein, R. Yeh, and E. B. Foa. 2015. Are 60-minute prolonged exposure sessions with 20-minute imaginal exposure to traumatic memories sufficient to successfully treat PTSD? A randomized noninferiority clinical trial. Behavior Therapy 46(3):328–341.

Opioid Therapy Chronic Pain Work Group. 2017. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Washington, DC: Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs.

Ouimette, P., D. Vogt, M. Wade, V. Tirone, M. A. Greenbaum, R. Kimerling, C. Laffaye, J. E. Fitt, and C. S. Rosen. 2011. Perceived barriers to care among Veterans Health Administration patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Services 8(3):212–223.

Park-Lee, E., R. N. Lipari, S. L. Hedden, L. A. Kroutil, and J. D. Porter. 2017. Receipt of services for substance use and mental health issues among adults: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review.

Pfeiffer, P. N., D. Ganoczy, N. W. Bowersox, J. F. McCarthy, F. C. Blow, and M. Valenstein. 2011. Depression care following psychiatric hospitalization in the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Managed Care 17(9):e358–e364.

Rosen, C. S., M. A. Greenbaum, J. E. Fitt, C. Laffaye, V. A. Norris, and R. Kimerling. 2011. Stigma, help-seeking attitudes, and use of psychotherapy in veterans with diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 199(11):879–885.

Rosen, C. S., M. M. Matthieu, S. Wiltsey Stirman, J. M. Cook, S. Landes, N. C. Bernardy, K. M. Chard, J. Crowley, A. Eftekhari, E. P. Finley, J. L. Hamblen, J. M. Harik, S. M. Kehle-Forbes, L. A. Meis, P. E. Osei-Bonsu, A. L. Rodriguez, K. J. Ruggiero, J. I. Ruzek, B. N. Smith, L. Trent, and B. V. Watts. 2016. A review of studies on the system-wide implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Veterans Health Administration. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 43(6):957–977.

Ruzek, J. I., and R. C. Rosen. 2009. Disseminating evidence-based treatments for PTSD in organizational settings: A high priority focus area. Behaviour Research & Therapy 47(11):980–989.

Schaefer, J. A., R. C. Cronkite, and K. U. Hu. 2011. Differential relationships between continuity of care practices, engagement in continuing care, and abstinence among subgroups of patients with substance use and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 72(4):611–621.

Smelson, D., D. Kalman, M. F. Losonczy, A. Kline, U. Sambamoorthi, L. S. Hill, K. Castles-Fonseca, and D. Ziedonis. 2012. A brief treatment engagement intervention for individuals with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Community Mental Health Journal 48(2):127–132.

Smith, E. R., K. E. Porter, M. G. Messina, J. A. Beyer, M. E. Defever, E. B. Foa, and S. A. Rauch. 2015. Prolonged exposure for PTSD in a veteran group: A pilot effectiveness study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 30:23–27.

Spoont, M. R., D. B. Nelson, M. Murdoch, T. Rector, N. A. Sayer, S. Nugent, and J. Westermeyer. 2014. Impact of treatment beliefs and social network encouragement on initiation of care by VA service users with PTSD. Psychiatric Services 65(5):654–662.

Stecker, T., B. Shiner, B. V. Watts, M. Jones, and K. R. Conner. 2013. Treatment-seeking barriers for veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts who screen positive for PTSD. Psychiatric Services 64(3):280–283.

Tate, S. R., J. Mrnak-Meyer, C. L. Shriver, J. H. Atkinson, S. K. Robinson, and S. A. Brown. 2011. Predictors of treatment retention for substance-dependent adults with co-occurring depression. American Journal on Addictions 20(4):357–365.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2010. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline: Management of opioid therapy for chronic pain. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2015. Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2016. Department of Veterans Affairs volume II, medical programs and information technology programs, Congressional submission FY 2017 funding and FY 2018 advance appropriations. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2017. Response to committee request for information. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA and DoD (Department of Defense). 2009. Management of substance use disorders (SUD). Management of Substance Use Disorders Working Group, Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense.

Villafranca, S. W., J. D. McKellar, J. A. Trafton, and K. Humphreys. 2006. Predictors of retention in methadone programs: A signal detection analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 83(3):218–224.

Wang, P. S., M. Lane, M. Olfson, H. A. Pincus, K. B. Wells, and R. C. Kessler. 2005. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62(6):629–640.

Watkins, K., and H. Pincus. 2011. Veterans Health Administration mental health program evaluation: Capstone report. Arlington, VA: RAND Corporation.

Watkins, K. E., B. Smith, A. Akincigil, M. E. Sorbero, S. Paddock, A. Woodroffe, C. Huang, S. Crystal, and H. A. Pincus. 2015. The quality of medication treatment for mental disorders in the Department of Veterans Affairs and in private-sector plans. Psychiatric Services 67(4):391–396.

Watts, B. V., B. Shiner, L. Zubkoff, E. Carpenter-Song, J. M. Ronconi, and C. M. Coldwell. 2014. Implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies for posttraumatic stress disorder in VA specialty clinics. Psychiatric Services 65(5):648–653.

Wu, P. C., C. Lang, N. K. Hasson, S. H. Linder, and D. J. Clark. 2010. Opioid use in young veterans. Journal of Opioid Management 6(2):133–139.

Zilcha-Mano, S., S. P. Roose, J. P. Barber, and B. R. Rutherford. 2015. Therapeutic alliance in antidepressant treatment: Cause or effect of symptomatic levels? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 84(3):177–182.

Zivin, K., D. Ganoczy, P. N. Pfeiffer, E. M. Miller, and M. Valenstein. 2009. Antidepressant adherence after psychiatric hospitalization among VA patients with depression. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 36(6):406–415.

This page intentionally left blank.