15

Quality Management

The concept of value-based health care is shaping the strategies that U.S. health care systems are using to deliver and manage patient care. Value-based health systems seek to provide quality care along various dimensions of quality (for example, safe, effective, and patient centered), with optimal results, at reasonable cost. Measuring health system performance by the structures, processes, and outcomes of the care and services provided—and using the results to inform effective organizational change—is integral to achieving the aims of quality and value. In addition, accessible, high-quality care that is consistently and reliably provided throughout the system depends on a health system’s capacity to harness, implement, and evaluate best practices that have been identified through measurement-based care strategies.

This chapter describes the programs that the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) uses for monitoring the quality of its mental health care and for ensuring the adoption of best clinical practices by VA providers. The committee did not assess the merits of the individual performance indicators the VA uses for quality management nor did it collect data for those indicators. Incorporating that information into the report in a meaningful way was beyond the available time and resources for this study, which focused on the collection and analysis of survey and site visit data and assessment of the literature as stated in the study charge.

QUALITY MEASUREMENT

Background

In health systems, systematic quality measurement is necessary for quality improvement, accountability and transparency, and informed decision making by patients. A well-defined and coordinated set of quality measures using administrative, clinical, and patient-reported data is necessary to track and improve clinical care quality and value. Derived from evidence-based practice guidelines, quality measures assess a health system’s performance in terms of its organizational structure, its care processes,

and, ultimately, its patient outcomes (Donabedian, 1988). In the Donabedian framework for assessing the quality of care, structure refers to the attributes of the settings in which care is provided, such as type/level of staffing, how many patients can be served, hours of operation, provider workloads, and availability of evidence-based practices. Process refers to the delivery of patient care in relation to clinical standards, for example, whether and how evidence-based practices are implemented, appropriate side-effect monitoring, and the frequency and timing of services. Outcomes are the effects of care on the health status of patients, which may be assessed by symptom severity, patient satisfaction, quality of life, and functional status. Patient outcomes are influenced by both the structure of care and the process of care.

Quality measures can apply to various levels of a health care system, such as hospitals, clinics, and clinicians. Administrative databases, patient medical records, and patient surveys are common data sources for quality measures. To identify gaps in quality and hold systems accountable for improvements, performance measures have been increasingly used in health care to compare processes of care against standards and benchmarks at the organizational, local, regional, and national levels (Kilbourne et al., 2010). The use of measures to improve care quality and health outcomes and deliver value-driven care requires data with a high degree of validity and reliability. Standardized measure definitions and data collection procedures give assurance that the results represent actual performance. The National Quality Forum (NQF), a private, nonprofit organization, was established in 1999 for the purposes of fostering consensus about standardized health care performance measures, reporting mechanisms, and a national strategy for quality improvement (Kizer, 2001). NQF has created a platform for consistent data collection and reporting, and it endorses measures meeting its measurement standards1 (NQF, 2016). NQF-endorsed measures are widely used in public reporting, quality improvement, and payment programs.

Mental Health Care Measurement Gaps

Few fully validated and reliable measures now exist for mental health care. More than 600 NQF-endorsed measures exist, but only a small proportion—38 measures—addresses adult mental health care.2 At the federal level, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has provisions supporting the development of performance measurement for greater quality, value, and safety in health care and promoting the collection of more extensive health information from public and private insurers (Rosenbaum, 2011). ACA activities intended to broaden the breadth of mental health care measures include the National Behavioral Health Quality Framework (SAMHSA, 2016) and the creation of a core set of standardized mental health measures for voluntary use by state Medicaid programs (CMS, 2016).

Since the 1990s, when the science of measurement for evaluating health care quality started being developed (Burstin et al., 2016), care in the general medical and surgical sectors has seen important quality gains in such areas as wellness screenings, diabetes care, and cardiovascular care (NCQA, 2015). However, gaps in mental health quality persist, and there has been a call for more focused efforts to develop measures, more dedication of resources, and greater leadership commitment (IOM, 2006; Pincus et al., 2011). More measures are needed that are aimed at psychosocial interventions, in particular to determine whether components of effective care are actually delivered to patients in these interventions. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies in Britain is one model for measurement in the area of psychosocial interventions (Pincus et al., 2016). Another important area to address is the development of better quality measures that assess mental health and general medicine integration (Pincus et al., 2016).

___________________

1 NQF uses five criteria to determine whether a measure is suitable for endorsement: (1) importance to measure and report, (2) scientific acceptability of measure properties, (3) feasibility, (4) usability and use, and (5) comparison to related or competing measures.

2 See http://www.qualityforum.org/Measures_Reports_Tools.aspx (accessed September 20, 2016).

One recent study (Farmer et al., 2016) developed prototype longitudinal electronic population-based measures of depression care suitable for evaluating the VA’s collaborative care management initiative at the primary care practice-site level.

Patient outcome measures are vital to the advancement of mental health quality efforts. Very few patient outcome measures exist, which is a significant obstacle in understanding effective mental care (IOM, 2006). In addition, in order to meet expectations of value in health care, mental health measurement and monitoring need to move in the direction of evaluating access, quality, and outcomes in the context of the costs to deliver that care (Schmidt et al., 2017).

MENTAL HEALTH CARE QUALITY MEASUREMENT IN THE DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS SYSTEM

The VA was at the forefront of the health care quality movement in the 1990s when rapid changes in measurement-based care started to emerge in the health care industry. Managed care systems transformed health care delivery through innovations in care coordination, health data and information technology, standardized care, performance standards, cost-containment strategies, and new incentives to drive provider and patient behaviors. During this time, the VA made it a priority to build a health system-wide infrastructure for managing performance, improving clinical care, and driving accountability, and the efforts produced demonstrable results (Kizer et al., 2000). Nearly 30 years later, some of these early programs and strategies have evolved and have continued to serve as valuable assets in the VA’s health care quality improvement infrastructure.

An overarching recommendation in the recent Independent Assessment of the Health Care Delivery Systems and Management Processes of the Department of Veterans Affairs was that the VA must adopt systems thinking to address problems of access, quality, cost, and patient experience (MITRE Corporation, 2015). Notably, the VA purchased care programs and veteran access and wait times—which have consequences for mental health delivery—are two areas evaluators described as failing to have a cohesive strategy that would connect solutions to broader organizational aims (IOM, 2015; RAND Corporation, 2015). The evaluators cautioned against tackling these problems independently because it can foster suboptimal, non-scalable, and non-sustainable solutions (MITRE Corporation, 2015). With this in mind, the committee believes performance information about the VA’s purchased care programs is a necessary component of a comprehensive quality improvement strategy for mental health. However, to the committee’s knowledge, there has been no systematic data collection and analysis of the quality of care or timeliness of care veterans receive through the Veterans Choice program (IOM, 2015; RAND Corporation, 2015).

The Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA’s) Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention (OMHSP) provides system-wide oversight of VA mental health care quality. OMHSP data systems and quality improvement guidance provide support to facility program managers responsible for using quality performance data and managing results (Trafton et al., 2013). The VA has a suite of performance information systems to monitor mental health care access and quality as well as to support opportunities for quality improvement (Schmidt et al., 2017). Some of the major data systems are described below.

Mental Health Information System

The Mental Health Information System (MHIS) is a system of more than 200 clinical quality and process-of-care measures that was designed to monitor the implementation of the requirements contained in the Uniform Mental Health Services Handbook, a guiding policy document that details the requirements for mental health clinical care delivery within the VA (VA, 2015). MHIS measures are aimed at

local facility program managers and are intended to support quality improvement at each hospital or clinic (Trafton et al., 2013).

Recently, the limitations of relying on the numerous individual, locally focused MHIS measures for quality improvement have been recognized. The shortcomings identified include a lack of measure focus, questionable measure quality, limited alignment between MHIS performance and broader system goals, the presence of substantial variability in facility performance, and a need to examine the allocation of resources necessary for quality improvement (Kizer and Jha, 2014; Lemke et al., 2017; Schmidt et al., 2017).

Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning

In 2015, to encourage greater management engagement with and support of mental health programming and improvement, the VA added a set of mental health care measures to Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL), an informatics system that had been previously established to monitor clinical quality (Lemke et al., 2017). SAIL is the VA’s system for measuring and benchmarking health care quality and efficiency at individual VA medical centers (VAMCs), and for enhancing the identification of quality improvement opportunities. To promote accountability, SAIL outcomes are included in every VAMC director’s performance evaluation.

SAIL includes a range of measures important for addressing access to care, the quality of health care, employee perception about the organization, nursing turnover, and efficiency. For example, the access domain includes a measure about wait times to mental health appointments. A mental health domain consists of three component scores (composites), each composed of multiple individual measures, that monitor the population coverage, the continuity of care, and the experience of care. Population coverage examines the proportion of potentially indicated patients who receive services. The continuity of care examines the likelihood of the receipt of follow-up or coordinated care. The experience of care examines veteran and mental health provider satisfaction with access and quality. The data are from two VA surveys, the Veteran Satisfaction Survey (VSS)3 and the Mental Health Provider Survey. The VSS is an annual survey consisting of a 30-item instrument that is administered by mail to veterans seen at VA health facilities. The VA executes the samples and mailings at 2-week intervals throughout the year and it reports the results for a particular year. The survey response rates are approximately 20 to 25 percent, which requires the VA to mail approximately 50,000 surveys annually in effort to reach a goal of 10,000 completed surveys per calendar year (VA, 2016d). The VA’s annual survey of mental health providers is a Web-based survey of all mental health providers. In 2015, the VA reported there were 25,879 filled mental health clinical positions and that more than 8,700 survey respondents completed the survey, for a response rate of 34 percent (VA, 2016e). Greater detail about the three SAIL mental health composites and the measures can be found in Lemke et al. (2017).

To assist program managers with SAIL performance improvement strategies, the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention has subject-matter experts assigned to each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) and facility. Since fiscal year (FY) 2016, approximately 50 face-to-face site visits and five virtual site visits have been provided to the facilities. Ongoing training sessions are provided for sites with lower SAIL performance; and training visits can also be arranged in response to site-specific requests (VA, 2017c). The VA reported to this committee that facilities that started FY 2016 with poorer access and quality have generally improved, while those facilities with excellent access and quality have generally maintained their performance over the course of the year (VA, 2017c).

___________________

3 Questions in the VSS are adapted from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems and the VA’s Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients.

Mental Health Management System

The VA created the Mental Health Management System (MHMS) to support a value-driven mental health system from a broader systems perspective. The MHMS uses clinical and organizational data to provide objective information for making decisions about which facilities get what resources, when, and how much and for engaging facility, VISN, and senior leadership in continuous quality improvement. The MHMS provides facility summary data on SAIL performance (described above), access, productivity, staffing, satisfaction, and programming (VA, 2017c). There are major limitations, however, such as that cost data and patient outcomes are not components of the MHMS (Schmidt et al., 2017).

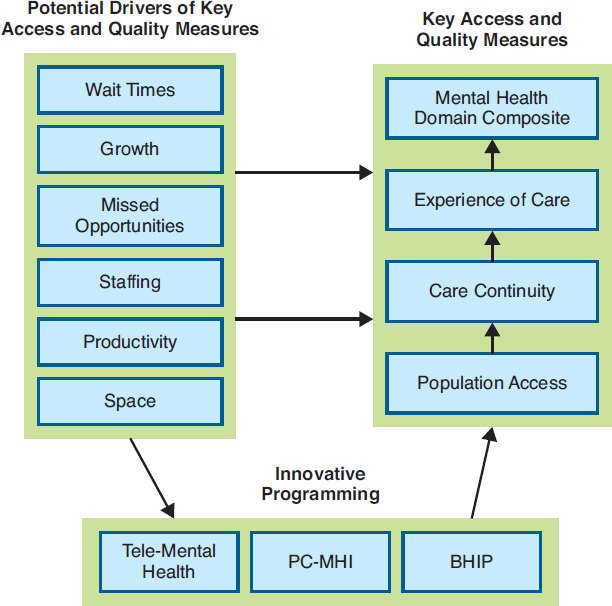

Figure 15-1 shows the MHMS framework for assessing access and quality (Schmidt et al., 2017). The MHMS includes 20 structure and efficiency measures related to the six potential drivers of access and quality that are shown in Figure 15-1. For example, wait time is one of the drivers, so one of the measures captures the proportion of patients who receive outpatient mental health care within 30 days of their preferred dates. The MHMS also has measures addressing tele-mental health, primary care-mental health integration (PC-MHI); and the Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program (BHIP), which influence the drivers of access and quality. For example, specific MHMS calculates the ratio of the number of tele-mental health patients to the number of total mental health outpatients in a facility, the ratio of PC-MHI patients to the total number of primary care patients, and whether the level of patient and provider involvement in BHIP is within the intended range.

NOTE: BHIP = Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program; PC-MHI = primary care–mental health integration.

SOURCE: Schmidt et al., 2017.

Schmidt et al. (2017) conducted a study of the MHMS that examined performance on 31 measures calculated for all U.S. VA health care facilities (N = 139). Overall, the researchers found that performance varied across facilities on MHMS measures. The analysis revealed that better access to care was significantly associated with fewer mental health provider staffing vacancies (r = 0.24), with higher staff-to-patient ratios for psychiatrists (r = 0.19) and other outpatient mental health providers (r = 0.27). In addition, higher staff-to-patient ratios were significantly associated with higher performance on a number of patient and provider satisfaction measures (range of r = 0.18–0.51) and continuity-of-care measures (range of r = 0.26–0.43). The researchers reported that the MHMS data about health system performance can be useful in VA management discussions about solutions to common problems such as challenges in management and organization, issues related to geography and location, and under-resourcing. The reported limitations of the MHMS included the lack of available patient outcome measures and cost data, and low veteran and provider survey response rates; however, it is noted that these are not unique to the VHA (Schmidt et al., 2017).

Patient Outcome Data

None of the data systems for assessing health care performance described above—MHIS, SAIL, MHMS—collects and uses standardized patient outcome data. Yet, ongoing monitoring of patient symptoms is essential to the assessment and improvement of patient care. The VA has reported that by 2018 it will complete the development of the first phase of a comprehensive system, the Mental Health Quality and Clinical Outcomes Reporting System, to monitor health outcomes with standardized patient-reported outcome measures (VA, 2016a).

Public Reporting

In support of transparency, accountability, improvement, and patient-centered care, the VA publicly reports facility-level performance on the SAIL measures, which include access and mental health domains (VA, 2016c). Data tables on the VA’s website give the facility score, the benchmark for the measure, and 10th, 50th, and 90th percentile scores. On an overall measure of quality, each VAMC is compared to other VAMCs using a 1- to 5-star rating system. The VA updates the SAIL reports quarterly and has also indicated an intention to report a VAMC’s performance compared to its previous year’s performance (VA, 2016c).

Consumer-friendly reports are available for veterans and other lay readers interested in seeing results on VA quality measures. The VA’s website has a searchable database4 from which veterans can get a facility’s star rating on several quality measures (VA, 2016b). One of the measures is related to routine mental health screening, which assesses whether veterans are appropriately screened for alcohol misuse, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at the required intervals and, if positive, receive appropriate follow-up evaluations (VA, 2016b). Another VA website5 presents information on such measures as wait times and patient satisfaction. In addition, the VA reports performance measures on the Medicare Hospital Compare website,6 which allows for the comparison of VA facilities with hospitals in the private sector.

___________________

4 See https://www.va.gov/QUALITYOFCARE/apps/mcps-app.asp.

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT INNOVATIONS

Identifying and spreading best practices can be a major driver of providing consistent, high-quality health care for veterans. The VA has been making advances in research into best practices and also the dissemination of the best practices it has learned and is continuing to learn since the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan began. In addition to its work on to performance measurement, as described above, the VA has an array of centers and initiatives that support its mental health services through evaluation, research, and clinical support. Chapter 3 describes a number of the key centers and initiatives. Many activities undertaken by the VA are related to improving the implementation of evidence-based therapies and evaluating outcomes at the program, facility, and regional levels. For example, the VA’s Northeast Program Evaluation Center has broad responsibilities within OMHSP to evaluate VA mental health care programs, including those for specialized treatment of PTSD.

As demonstrated in the review of mental health delivery in Chapter 11, research shows that within the health care industry—and within the VA specifically—the adoption of evidence-based treatments into clinical practice is suboptimal. The field of implementation science is seeking to understand the barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation strategies that successfully integrate research science into health care practice and policy (Cook and Wiltsey-Stirman, 2015). Along these lines, the VA’s Quality Enhancement Research Initiative and Diffusion of Excellence Initiative are resources that support the provision of effective care and the use of best practices.

Quality Enhancement Research Initiative

As described in Chapter 3, the mission of the VA’s Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) is to improve the health of veterans by supporting the more rapid implementation of effective clinical practices into routine care and by evaluating the results of those efforts. The QUERI program consists of 15 interdisciplinary programs involving cross-cutting partnerships to achieve VA national health care priority goals and specific implementation strategies. In the area of mental health, for example, the QUERI for Team-Based Behavioral Health (located in Little Rock, Arkansas) focuses on how team-based behavioral health care can be improved through the use of implementation facilitation strategies, with anticipated improvements in veteran outcomes. The mission of the Center for Mental Health and Outcomes Research (located in North Little Rock, Arkansas) is “to optimize outcomes for veterans by conducting innovative research to improve access to and engagement in evidence-based mental health and substance use care” (VA, 2017a). Its focus is research aimed at improving mental health care for rural veterans. There is also a Care Coordination QUERI (located in Los Angeles, California) that aims to learn how to improve coordination between the veteran, his or her primary care team, and any specialty care, emergency department, hospital, and home community resources the veteran may need (VA, 2017b).

Diffusion of Excellence Initiative

The size and scope of the VA health system—more than 1,700 sites of care and more than 300,000 employees—makes it inherently challenging to deliver care with consistent processes and outcomes across the system (Clancy, 2016). Recently, the external evaluation of VA care under the Veterans Choice Act recommended a systematic effort “to identify unwarranted variation, identify and develop best practices to improve performance, and embed these practices into routine use across the VA system” (MITRE Corporation, 2015, p. B3). In response, with the support of QUERI, the VA launched the Diffusion of Excellence initiative to spread and implement best practices in the VA nationally that

address the priority areas in access, employee engagement, care coordination, and quality and safety. The specific goals of the Diffusion of Excellence Initiative are to identify clinical and administrative best practices, to disseminate these practices to other sites of care, and to encourage the standardization of practices that deliver positive outcomes for veterans and their families. As of September 2016, this diffusion model had generated more than 260 ongoing innovations in 70 facilities (Clancy, 2016). Examples of mental health projects selected for replication include an information technology solution called e-Screening which veterans use to complete mental health screening questions directly into the medical record (increasing needed mental health referrals or interventions by 34.6 percent per year, or 325 veterans, for veterans at high risk for suicide); and a home-based mental health evaluation program for rural veterans (designed to reduce psychiatric rehospitalizations by 50 percent) (Elnahal et al., 2017).

VA’s QUERI and Diffusion of Excellence programs reflect a learning approach to health care system improvement. In learning health care systems, science and informatics, patient–clinician partnerships, incentives, and culture are aligned to promote and enable continuous and real-time improvement in both the effectiveness and the efficiency of care (IOM, 2013). Systems that continuously improve by capturing and broadly disseminating lessons learned from every health care experience and new research discovery are exemplary models for achieving high-quality, high-value health care (IOM, 2013; Smith et al., 2012).

SUMMARY

- The VA has a long history of taking important steps to improve the care and services it provides to veterans. The committee found that the VA currently has many key initiatives aimed at measuring system performance to improve mental health care access and quality. Examples of those efforts include the expansion of quality management data systems with more measures of mental health care, the use of performance data to encourage greater engagement by VA management in mental health programming and improvement, the conduct of research (through QUERI resources, for example) to identify best practices for improved access and quality, and the creation of the Diffusion of Excellence Initiative which seeks to facilitate the routine use of effective practices across the health system. The VA’s programs to train health care clinicians on evidence-based mental health treatments (discussed in Chapter 8) and to promote the use of those treatments by clinicians (discussed in Chapter 11) are other ways the VA has increased its capacity to provide evidence-based care.

- The committee found that the VA has a number of health information systems supporting data collection and analysis that can guide quality management, but questions remain about how well these systems produce internal assessments that drive the system to be more patient centered and value driven, while improving access and quality.

- Examples of service problems described in the report suggest that the VA does not appear to be generating and using its own data to improve what is wrong in the mental health system. More attention is needed on identifying the sources of variation across VISNs and VAMCs and using performance data about the various access and quality domains to establish targeted quality improvement efforts.

- None of the data systems for quality management described in this chapter (MHIS, SAIL, MHMS) collects and uses patient outcome data, which is a significant barrier to quality improvement. The VA has reported it is in the process of developing a comprehensive system to monitor health outcomes with standardized patient-reported outcome measures. In addition, there is limited use of cost data in VA quality assessments, which is necessary in the pursuit of value-driven care.

- To the committee’s knowledge, the VA does not conduct systematic data collection and analysis of the quality of care or timeliness of care veterans receive through VA-purchased care programs, including the Veterans Choice Program. This is a significant gap in the VA’s quality management of mental health care for veterans.

- Recent evaluations of the VA’s collection and reporting of staff productivity data, which is discussed in Chapter 12, have found that problems associated with insufficient metrics and data accuracy limit the usefulness of these data for identifying opportunities to improve productivity and efficiency.

- In support of transparency, accountability, improvement, and patient-centered care, the VA has increased the amount of publicly available information about the performance of the health system in access and mental health domains. However, relative to measures on other types of health care services the VA provides, only a small number of mental health measures are available to the public.

REFERENCES

Burstin, H., S. Leatherman, and D. Goldmann. 2016. The evolution of healthcare quality measurement in the United States. Journal of Internal Medicine 279(2):154–159.

Clancy, C. 2016. Statement of Carolyn Clancy, M.D., deputy under secretary for organizational excellence, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, before the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, September 7, 2016. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2016. Adult health care quality measures. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/performance-measurement/adult-core-set/index.html (accessed October 31, 2016).

Cook, J. M., and S. Wiltsey-Stirman. 2015. Implementation of evidence-based treatment for PTSD. PTSD Research Quarterly 26(4):1–3.

Donabedian, A. 1988. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 260(12):1743–1748.

Elnahal, S. M., C. M. Clancy, and D. J. Shulkin. 2017. A framework for disseminating clinical best practices in the VA health system. JAMA 317(3):255–256.

Farmer, M. M., L. V. Rubenstein, C. D. Sherbourne, A. Huynh, K. Chu, C. A. Lam, J. J. Fickel, M. L. Lee, M. E. Metzger, L. Verchinina, E. P. Post, and E. F. Chaney. 2016. Depression quality of care: Measuring quality over time using VA electronic medical record data. Jouirnal of General Internal Medicine 31(1):36–45.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2006. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions: Quality chasm series. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2013. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2015. Health care scheduling and access: Getting to now. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kilbourne, A. M., D. Keyser, and H. A. Pincus. 2010. Challenges and opportunities in measuring the quality of mental health care. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 55(9):549–557.

Kizer, K. W. 2001. Establishing health care performance standards in an era of consumerism. JAMA 286(10):1213–1217.

Kizer, K. W., and A. K. Jha. 2014. Restoring trust in VA health care. New England Journal of Medicine 371(4):295–297.

Kizer, K. W., J. G. Demakis, and J. R. Feussner. 2000. Reinventing VA health care: Systematizing quality improvement and quality innovation. Medical Care 38(6 Suppl 1):I7–I16.

Lemke, S., M. T. Boden, L. K. Kearney, D. D. Krahn, M. J. Neuman, E. M. Schmidt, and J. A. Trafton. 2017. Measurement-based management of mental health quality and access in VHA: SAIL mental health domain. Psychological Services 14(1):1–12.

MITRE Corporation. 2015. Independent assessment of the health care delivery systems and management processes of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Volume I: Integrated report. McLean, VA: MITRE Corporation.

NCQA (National Committee for Quality Assurance). 2015. The state of health care quality 2015. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance.

NQF (National Quality Forum). 2016. Measure evaluation criteria and guidance for evaluating measures for endorsement. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum.

Pincus, H. A., B. Spaeth-Rublee, and K. E. Watkins. 2011. The case for measuring quality in mental health and substance abuse care. Health Affairs 30(4):730–736.

Pincus, H. A., S. H. Scholle, B. Spaeth-Rublee, K. A. Hepner, and J. Brown. 2016. Quality measures for mental health and substance use: Gaps, opportunities, and challenges. Health Affairs (Millwood) 35(6):1000–1008.

RAND Corporation. 2015. Assessment C (Care authorities). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation,

Rosenbaum, S. 2011. Law and the public’s health. Public Health Reports 126(1):130–135.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2016. National behavioral health quality framework. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/national-behavioral-health-quality-framework (accessed October 31, 2016).

Schmidt, E. M., D. D. Krahn, M. H. McGuire, S. Tavakoli, D. M. Wright, H. E. Solares, S. Lemke, and J. Trafton. 2017. Using organizational and clinical performance data to increase the value of mental health care. Psychological Services 14(1):13–22.

Smith, M., G. Halvorson, and G. Kaplan. 2012. What’s needed is a health care system that learns: Recommendations from an IOM report. JAMA 308(16):1637–1638.

Trafton, J. A., G. Greenberg, A. H. Harris, S. Tavakoli, L. Kearney, J. McCarthy, F. Blow, R. Hoff, and M. Schohn. 2013. VHA mental health information system: Applying health information technology to monitor and facilitate implementation of VHA Uniform Mental Health Services Handbook requirements. Medical Care 51(3 Suppl 1):S29–S36.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2015. Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2016a. Department of Veterans Affairs, Volume II: Medical programs and information technology programs. Congressional submission FY 2017 funding and FY 2018 advance appropriations. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2016b. Quality of care: How does your medical center perform. https://www.va.gov/QUALITYOFCARE/apps/mcps-app.asp (accessed March 6, 2017).

VA. 2016c. Strategic Analysis for Improving and Learning (SAIL). https://www.va.gov/QUALITYOFCARE/measure-up/Strategic_Analytics_for_Improvement_and_Learning_SAIL.asp (accessed March 6, 2017).

VA. 2016d. Mental Health Satisfaction Survey: Veteran Satisfaction Survey (VSS) national results. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2016e. National Mental Health Providers Survey: 2015. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health Operations.

VA. 2017a. COIN: Center for Mental Healthcare and Outcomes Research (CeMHOR), North Little Rock, AR. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/centers/cemhor.cfm (accessed January 18, 2017).

VA. 2017b. National network of QUERI programs. http://www.queri.research.va.gov/programs/default.cfm (accessed March 6, 2017).

VA. 2017c. Response to committee request for information. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.