12

Efficient Mental Health Care

Efficient health care systems strive to produce better outcomes for lower costs and use resources in a manner that obtains the best value. There are a variety of approaches for monitoring and improving health system efficiency. This chapter reviews literature on how well the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) tracks mental health system efficiency in terms of staff productivity and describes the VA’s implementation of programs with a goal of increasing integration, which in some cases, enhances efficiency of care. Aspects of efficiency are also addressed in other chapters of the report. For example, the committee discusses the use of information technologies in Chapter 14, which can improve the flow of clinical information and support clinical decision making, as well enhance care delivery (i.e., telehealth). The use of data to identify system inefficiencies and improve processes and resource use to deliver effective care is addressed in Chapter 15.

MENTAL HEALTH WORKFORCE TRACKING AND EFFICIENCY

As discussed in Chapter 8 in the discussion of the VA workforce, the committee identified issues with the adequacy of staffing levels for mental health personnel. In an effort to address some staffing inefficiencies, the VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention (OMHSP) currently tracks onboard outpatient mental health providers. However, data on mental health workforce provided by OMHSP to the committee did not include information about either social workers or nurses, two of the core mental health professions. Currently the VA lacks the ability to differentiate social workers and nurses who specialize in mental health from other VA employees in these professions (VA, 2017). Given both the unique contributions of each mental health profession, and the significant overlap in scope of practice across mental health professions (see Chapter 4, Table 4-4), the lack of these data is problematic in terms of assessing the size and distribution of the VA mental health workforce and its ability to respond to the mental health needs of veterans. Similarly the VA’s information about the nurs-

ing workforce often fails to separate out advanced practice psychiatric nurses, whose expanded scope of practice includes much-needed capacities, such as comprehensive health assessment and diagnosis and medical management of psychiatric disorders. The VA recently reported that it plans to begin tracking inpatient, residential, and homeless program providers as well to help optimize workforce placement efficiency. The VA is also considering capturing additional staffing data by subspecialty program (such as specialty substance use disorder and primary care–mental health integration). This should improve the VA’s ability to track staffing for specialty programs, which are currently tracked using self-report survey data (VA, 2016c).

Workforce Productivity

The VA uses clinical productivity measures to monitor the time and effort providers spend delivering care. The units of measurement are work-relative value units (wRVUs) which quantify workload based on time, mental effort and judgment, technical skill and effort, and stress involved in delivering an episode of care. wRVUs are automatically calculated based on the recorded procedures on a patient’s electronic medical record (Grant Thornton LLP, 2015).

A comparison of provider productivity between the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and the private sector found that VA mental health care providers see more encounters than private-sector providers and exceed industry productivity benchmarks (Grant Thornton LLP, 2015). However, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) notes in a 2017 report that the metrics the VA uses to track productivity are insufficient, may not provide quality information, and thus may not accurately reflect actual clinical productivity and efficiency (GAO, 2017). In 2015, RAND reported a similar finding (RAND, 2015). For example, contract positions and advance-practice providers (such as nurse practitioners) are not captured in the productivity data. The GAO also noted that providers do not always accurately code the intensity of their work or the time they spend performing clinical duties. The inaccurate workload and staffing data feed the VA’s efficiency models, which results in inaccurate modeling. The GAO notes that the VA central office has developed an analytic tool Veterans Affairs medical centers (VAMCs) can use to identify the drivers of low productivity. However, the VA does not systematically oversee VAMCs’ efforts to monitor productivity and efficiency. Nor does the VA require VAMCs to monitor efficiency models. As a result, the VA may be unable to effectively determine factors that contribute to low productivity and may be missing opportunities to identify best practices to improve productivity, and thus improve access to care for veterans (GAO, 2017).

The GAO recommends that the VA expand metrics to include all providers, improve training for coding clinical procedures, require VAMCs to monitor and improve clinical efficiency, and develop a process to oversee VAMCs plans for improving productivity. While the VA concurred, at least in principle, to all the recommendations, the GAO was concerned that some of the VA’s outlined plans to address the recommendations did not fully address the issues outlined in the report (GAO, 2017).

CARE INTEGRATION AND COLLABORATION

In this section, the committee presents information about the VA’s use of evidence-based care delivery approaches that systematically coordinate care given by the VA’s primary care, mental health, and substance-use treatment providers to effectively treat patients with mental health conditions. As discussed below, some research suggests that care coordination can improve efficiency through reduced fragmentation of care and improved patient care. This section reflects the research literature on care integration in general and within the VA.

Background

There are various definitions, models, and strategies used in health care practices today that relate to the objective of improving health through better integration and coordination. Many different terms are used in the field of health integration, such as mental health integration, behavioral health integration, coordinated care, collaborative care, integrated care, and shared care (Gerrity, 2016).

A leading conceptual framework of collaboration and integration, jointly funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Health Resources and Services Administration, organizes integration models into three main categories—coordinated, co-located, and integrated care—with two levels of degree within each category (Gerrity, 2016; Heath et al., 2013). See Box 12-1, below.

There is a robust body of evidence supporting collaborative and integrated mental health including multiple systematic reviews of more than 90 randomized controlled trials involving over 25,000 patients (Gerrity, 2016). The research demonstrates that collaborative care approaches are effective in treating mental health conditions (such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation), can be cost effective, and are sustainable across various populations and settings. In addition, the coordination of care across clinicians and settings has been shown to result in greater efficiency through reduced fragmentation of care and improved patient outcomes (AHRQ, 2012; Archer et al., 2012; Belsher et al., 2016; Gerrity, 2016; IOM, 2006). The 2014 Institute of Medicine report Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Military and Veteran Populations: Final Assessment urged the VA and the Department of Defense to expand integrated and coordinated care for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (IOM, 2014). Integrated care in the veteran population is discussed in the next section.

Care Integration and Collaboration at the Veterans Health Administration

Primary Care-Mental Health Integration (PC-MHI)

Primary care-mental health integration (PC-MHI) is the VA’s coordinated care approach for delivering mental health care services to veterans in collaboration with primary care providers. PC-MHI is implemented within the VA’s patient-centered medical home model known as the Patient-Aligned Care Team (PACT) (see more about PACT in Chapter 10). In 2008 the VA mandated that all VA medical centers and large community-based outpatient clinics have integrated mental health services operating in primary care clinics. The two core components of PC-MHI programs are care management and co-located collaborative care services (Pomerantz and Sayers, 2010; VA, 2008).

Co-located collaborative care involves embedding mental health professionals within primary care settings to facilitate collaboration with primary care providers. Co-located collaborative care providers follow up on positive mental health screens, hold conjoint appointments, educate providers on the assessment and treatment of mental health concerns, and collaborate in comprehensive treatment planning, which often includes brief behavioral interventions that are appropriate for the primary care setting. For patients with more severe or complex conditions, co-located collaborative care providers facilitate referrals to specialty mental health care, which are often delivered same day (Beehler et al., 2015).

Care management activities, which are often telephone based and delivered by nursing staff, include ongoing patient assessment, service coordination (including facilitating communication between primary care and mental health providers), treatment adherence monitoring, and patient education. The care management approaches supported in VA primary care settings include the Behavioral Health Laboratory, which provides evidence-based clinical services supporting mental health and substance abuse management as well as Translating Initiatives in Depression into Effective Solutions (Beehler et al., 2015).

PC-MHI Effectiveness

Studies involving the veteran population have found that the VA’s PC-MHI program is an effective approach to integrating mental health in primary care. The use of PC-MHI has been found to be associated with an increase in psychiatric diagnosis detection rates (Bohnert et al., 2016; Brawer et al., 2011; Zivin et al., 2010) and with increased odds of a patient initiating and continuing treatment (Bohnert et al., 2013, 2016; Brawer et al., 2011; Szymanski et al., 2012). PC-MHI is also improving access to services. Seal et al. (2011) found that among 526 Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans, veterans seen in an integrated care clinic were significantly more likely to receive mental health evaluations within 30 days of their initial visit than those receiving usual (non-integrated) primary care (men: odds ratio [OR] 1.30; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.13–1.50; women OR 2.94; 95% CI = 1.41–6.18). The authors suggest that these same-day evaluations provide an opportunity to initiate the interventions immediately or to provide an immediate referral to additional services as needed. Research also shows that PC-MHI appears to be reaching veterans in demographic subgroups that are traditionally less likely to use specialty mental health care; the users tend to be slightly younger, female, nonwhite, nonmarried, and without substantial service-connected disability status (Johnson-Lawrence et al., 2012).

In addition, studies show that PC-MHI is associated with a lower risk of poor outcomes for veterans with mental illness. Trivedi et al. (2015) examined whether PC-MHI involvement was associated with a decreased risk of emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and mortality among 1,147,022 veterans diagnosed with a mental disorder and seen within VA primary care settings from April 2010 to March 2011. Researchers found that having at least one contact with PC-MHI was associated with better outcomes (lower odds of an ED visit, hospitalization, and mortality) among veterans with PTSD,

depression, substance use disorder, serious mental illness, and anxiety, compared with patients who did not have PC-MHI, although not all improvements across every disorder–outcome combination were significant. This finding is consistent with other research showing that collaborative care models mitigate the risk of poor outcomes that can be associated with mental illnesses (AHRQ, 2012; Archer et al., 2012; Gerrity, 2016).

PC-MHI Implementation

The VA reports that it provided more than 1 million PC-MHI encounters in 2015, which represents an increase of 8 percent from 2014 and an increase of 28 percent from 2013. According to the VA, the PC-MHI program is widely established across the system: 98.5 percent of the very large and 81.2 percent of large community-based outpatient clinics have implemented the program (VA, 2016a). However, significant local variation in PC-MHI implementation exists across VA sites nationally, with providers engaging in co-located collaborative care only, in care management only, or in combined co-located collaborative care and care management functions (Beehler et al., 2015).

Beehler et al. (2015) assessed PC-MHI program implementation by examining PC-MHI provider adherence to either care management or co-located collaborative care. To explore PC-MHI provider adherence to PC-MHI-specific tasks or procedures, the investigators analyzed self-report data captured with a psychometrically valid instrument, the Primary Care Behavioral Health Provider Adherence Questionnaire. The respondents were 173 VHA mental health providers (30 percent response rate) who had provided clinical services in primary care for at least 25 percent of their duties in 2012. The findings showed that a majority of mental health providers demonstrated moderate levels of adherence, with the levels of adherence differing by provider educational background and psychotherapy approach, the level of clinic integration, and previous PC-MHI training. Adherence was typically lowest in relation to collaboration with other primary care staff. The investigators concluded that PC-MHI providers could clearly benefit from multiple support strategies regarding how to overcome barriers to integration with primary care teams. The investigators indicated that while the use of provider tools and additional training in interprofessional communication may be important, achieving high levels of clinic integration will likely require addressing the larger organizational context through improved leadership support, the articulation of shared goals across teams, and systematic quality improvement efforts. Moreover, PC-MHI practice guidelines, which do not exist currently, may be especially beneficial in addressing undesirable variations in care (Beehler et al., 2015).

Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program

The Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program (BHIP) is a team-based program designed for the general outpatient mental health setting within the VA. BHIP teams, which are composed of mental health professionals and administrative staff, work together to focus on the veteran’s mental health and well-being. Mental health professionals engaged in BHIP can include psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers, marriage and family therapists, clinical pharmacists, licensed professional mental health counselors, peer specialists, and others (Weaver, 2014). BHIP’s goals are to provide improved access to care tailored to a veteran’s needs and facilitated by collaborative and coordinated care management. An incremental VA-wide implementation of BHIP was initiated in 2014. All VA facilities have initiated at least some level of implementation of BHIP teams, although the extent of implementation varies across sites (Barry et al., 2016).

Barry et al. (2016) conducted a formative evaluation to gather information about the implementation of BHIP in order to understand staff members’ perspectives on the benefits and challenges of the BHIP model. The benefits of BHIP listed by staff included increased staff communication, supportive relationships, shared decision making, and high quality of care for veterans. The challenges hampering BHIP implementation and team functioning cited by staff were a lack of well-defined or overlapping BHIP roles (for example, clinical management roles), staffing shortages, a lack of knowledge about BHIP principles or expectations, and a lack of leadership guidance. In addition, difficulty finding time in staff schedules and a lack of dedicated BHIP team meeting time for staff reduced participation in team meetings.

Stepped-Care Approaches

As barriers to mental health care remain exacerbated by growing demand and shortage of manpower, a type of integrated care, called stepped care, is being viewed as a strategy to achieve greater service efficiency. Stepped care seeks to treat patients at the lowest appropriate intensity of care that is still likely to provide benefits, to monitor a patient’s progress longitudinally, and to reserve more intensive treatments for those patients who do not benefit from first-line treatments or for those with more complex clinical presentations (Firozi, 2017; VA, 2016b).

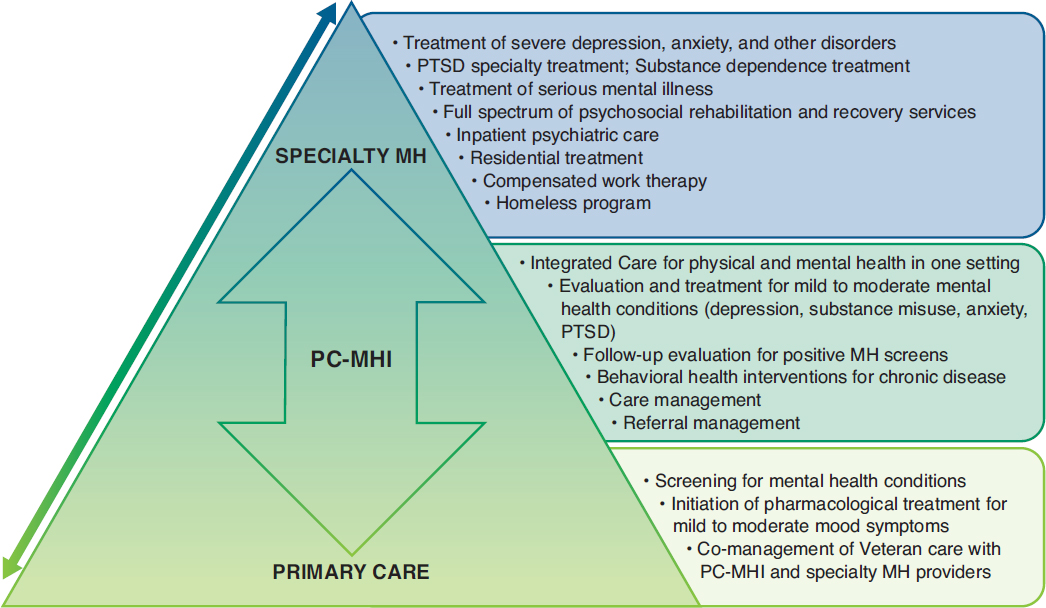

Box 12-2 shows the components of the VA’s version of a stepped-care approach for patients with a primary diagnosis of PTSD, depression, substance use disorder, and other mental health conditions (Patel et al., 2015). PC-MHI is the first line of the stepped-care model. Patients needing long-term mental health care are assigned to a collaborative team in BHIP. Complex cases are managed in specialty care and inpatient settings. The VA has used team-based models designed to address the needs of patients with particular mental health conditions, such as PTSD clinical teams and mental health intensive case management (MHICM) for patients with serious mental illness. However, more recently, team-based care models within general (rather than specialty) outpatient mental health settings have been implemented (Barry et al., 2016).

The goal of the VA’s stepped-care model for mental health is to provide care at the lowest appropriate level possible. Figure 12-1 provides more detail about the continuum of VA mental health care services.

While research has been conducted on the implementation of the component parts of the stepped-care model (for example, PC-MHI, BHIP), the committee is not aware of any research that has evaluated the effectiveness of the VA’s stepped care model as a whole. Research findings about stepped-care models are relevant to concerns regarding the VA’s limited capacity to ensure that adequate mental health resources are available to meet the needs of veterans.

SOURCE: Patel et al., 2015.

In the first large, randomized effectiveness trial on collaborative care for PTSD and depression in the military health system (Belsher et al., 2016; Engel et al., 2014, 2016), researchers compared a stepped-care model, Stepped Enhancement of PTSD Services Using Primary Care (STEPS-UP) with the usual care, an integrated mental health approach called RESPECT-Mil. Patients with probable PTSD or depression or both were recruited at six large military treatment facilities, and 666 patients were enrolled and randomized to STEPS-UP or the usual collaborative care.

Engel et al. (2016) found that the stepped-care model, STEPS-UP, resulted in improved PTSD and depression outcomes above the traditional collaborative care model, RESPECT-Mil, in the military health system. Belsher et al. (2016) reported that STEPS-UP was more effective at increasing the quantity of mental health care services received across primary care and mental health specialty care settings as well as increasing psychiatric medication uptake and coverage. The use of STEPS-UP resulted in a more careful triage of patients, so that those with a comorbid diagnosis were more likely to be sent to specialty care and receive a greater quantity of care than those with less clinical complexity. In contrast, patients receiving care as usual all had the same likelihood of being referred to specialty care, regardless of their clinical complexity. The investigators concluded that managing less symptomatic patients in the lower steps might be efficient and cost effective and might also improve specialty care access for more clinically complex patients.

Private-Sector Partnerships for Veterans and Families

A new model of mental health care is trying to remove barriers to mental health care for veterans as well as their families; family members are generally not eligible to receive care at the VA and there-

fore must seek care elsewhere. Veterans’ family members seeking care in the community may find it difficult to receive care that is both sensitive to the issues that veterans’ families face and coordinated across providers.

In New York State, a partnership between the VA health system and a private-sector provider was established to create a mental health center that co-locates and coordinates care for veterans and their families. The Northwell Health System and the Northport Veterans Affairs Medical Center created the Unified Behavioral Health Center (UBHC) for Military Veterans and Their Families, which offers coordinated care for veterans and their families by locating VA and private providers side by side at the same facility. While the center was not designed to be fully integrated—one side serves veterans, and the other side is available to service members, veterans, and their families, with each side having separate entrances, information systems, and performance-monitoring processes—the infrastructure supports the coordination of care. There is convenient access to mental health services for all participants, and the exchange of information between the different sides is facilitated through team meetings, other in-person interactions, and phone contact among providers (Eberhart et al., 2016).

RAND researchers conducted an evaluation of the center’s activities to assess the viability of this new approach to mental health care, identify implementation challenges and successes, and assess the impact on patient health. The evaluation team found that the patients reported satisfaction with their experiences at the center and the care they received. In addition, there is preliminary evidence of improved health outcomes (Eberhart et al., 2016). Adult patients showed improvements in symptoms of depression and PTSD, in family functioning, and in the quality of life. Child patients exhibited fewer mental health problems. The RAND team concluded that the UBHC has the potential to be helpful to the veterans and families it serves, and the team made several recommendations for improving the model. Areas for improvement include enhancing collaboration, expanding staffing and space, delivering a continuum of evidence-based services, and prioritizing outcome monitoring and quality improvement (Eberhart et al., 2016).

FINDINGS FROM THE COMMITTEE’S SITE VISITS

From the site visit information, the committee identified several ways the VA has taken steps to improve the efficiency of the mental health services it delivers. These include offering evidence-based practices (EBPs), time-limited services, shorter appointments, and group treatment sessions (versus individual sessions), which can serve more patients within the allotted time.

Veterans expressed mixed feelings about group treatment modalities. Those who reported positive experiences said that being in a group helped them feel less isolated in their experiences. A typical response was, “I was able to realize that I wasn’t alone. I’m going through a lot of the same things that other veterans are going through.” [Washington, DC]

However, negative reactions to group therapies were also expressed to the site visitors. As a clinician explained:

For an average veteran who is afraid to talk about his issues in groups, he’ll . . . have that first appointment with someone individually. Then the next referral would be to a group. That is often too much for them. They’ll wash out of that one. [Temple, Texas]

Many veterans said that groups were a “second-best” treatment that impeded progress in resolving their issues, given the limited time available to discuss their problems and the lack of privacy inherent in group discussions. As one disgruntled veteran remarked, “I was like ‘Step back! Won’t be doing group no more.’”

An additional concern was that hearing other veterans’ accounts of trauma was re-traumatizing. The spouse of an Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND) veteran said that her husband’s participation seemed to make him more symptomatic: “I noticed he was getting more depressed. He’d come home and tell me the stories of the people that were there . . . things he couldn’t relate to.” [East Orange, New Jersey]

In contrast to the mixed reviews of group therapy for substance use disorder and mental problems, another type of group—psychoeducational—was viewed as helpful. Most VA medical centers provide psychoeducational groups—or “classes,” as veterans and VA clinicians referred to them. Their purpose is to acquaint veterans with the services offered by the VA, provide information about the sequelae of military trauma, and teach coping skills. Many veterans found the classes helpful for understanding their experiences of PTSD and adjusting to life after deployment. As one noted:

I started showing up for [the group]. . . . I read all these symptoms . . . every single word in it—I experienced for so many years. I was so overwhelmed that I decided to go to the restroom. . . . After I came back, I continued with the class. [Palo Alto, California]

While the VA has taken steps to improve service efficiency, this does not mean that the course of treatment is shortened for all veterans. Site visit interview data indicate that a number of OEF/OIF/OND veterans were receiving psychotherapy services from the VA for multiple years. For these individuals, a more intensive cognitive processing therapy (CPT) or prolonged exposure (PE) therapy was helpful and then was followed up with “checking in” with a psychotherapist monthly or every other month. One such veteran explained:

Now I come to check in once every two months. . . . Sometimes I’ve been stuck in traffic trying to get here and Dr. [psychologist] will call me and say, “Hey, are you okay? Do you need anything? How is everything going?” If I need anything more, all I have to do is call and set up another appointment. [Tampa, Florida]

In contrast to this “stepped-down” approach, many veterans reported treatment histories marked by multiple short-term, but intensive, treatments provided by the VA. These episodes of intensive treatment were punctuated by years of less intensive monthly, semimonthly, or bimonthly psychotherapy visits. Other veterans had psychiatric visits alongside participation in groups. As one veteran reported:

I’ve been in five groups. I’m in a permanent group with these guys [gestures to other veterans in room] now, and I like it. It’s for veterans of OEF/OIF. I got a psychiatrist, as they do. I’ve seen her once every 3 months. [Seattle, Washington]

Other times, veterans seemed to have little ongoing clinical management. Site visitors spoke with a veteran in Temple, Texas, who said he had experienced residential PTSD treatment three times. This veteran seemed to have real difficulties functioning without ongoing help. He said, “One of the scariest things is to actually leave the [residential PTSD] program, because all those wounds, all those scars, all those memories are so open and then you go back in the world. The first time I came through the program, I got in trouble 5 months after with the law.” A veteran in Seattle, Washington, explained that he was treated in three residential programs back-to-back: “I did a [residential] substance abuse program. That was 28 days. Turned around and immediately transferred over to the PTSD program. That was another 28 days. Now I’m in the sixth month of a [VA program for homeless veterans with mental health issues].”

A VA provider explained that providing EBPs sequentially was a strategy for managing patients with treatment-resistant disorders. She gave an example of one such veteran:

She’s [veteran] been through PE, CPT . . . we’re doing ACT [acceptance and commitment therapy] for PTSD and depression right now. This is a really good example of, “All right, we’re going to try the things we have . . . and as soon as we get new ones, we’re going to keep offering.” [Palo Alto, California]

These veterans experience numerous EBPs whose efficacy has been assessed only as a single course of treatment. Whether patients benefit from repeating courses of outpatient and residential treatments is unclear, and the anecdotal evidence offered by VA clinicians suggests that it may not be beneficial. More attention to designing best practices for the efficient and effective clinical management of chronic, non-psychotic psychiatric disorders seems warranted.

Finally, VA clinicians described protocols for mental health visits that left them with insufficient time to address patients’ presenting problems. A VA clinician offered this anecdote:

I saw a patient over the weekend and admitted him while on call . . . for the last 6 weeks he’d been smoking crack cocaine and drinking a pint of whisky a day. I asked him, “How do you afford all that?” He said, “Doc, I steal and I swindle. That’s what I do to survive.” This guy—it really hits you hard emotionally to see someone who’s fallen that low. You want to help them. But according to my documentation, I need to ask him next, “So what do you do in your leisure time?” It’s not appropriate to ask that at that point. I need to be the judge of that. [Temple, Texas]

Another clinician at a different site [Chicago, Illinois] explained that if he “filled out all the questionnaires [documentation] correctly, I wouldn’t be able to take care of patients. We all check boxes.” This clinician went on to describe how the protocols make the provider seem insensitive: “You [veteran just] told me that you’re really happy because a wonderful thing happened. You’re [clinician] like, ‘Well, it’s the annual depression scale, so let’s ask you about whether you’re depressed.’”

Some providers said that practicing this way leaves the false impression that veterans are receiving quality mental health care. As one explained, “Oh, we had 5,000 veterans last year . . . 5,000 times the questions were answered. We’re doing our job.” [Chicago, Illinois]

SUMMARY

Based on findings from the committee’s site visits and literature research, this chapter presented information about evidence-based care delivery approaches that achieve efficiency by systematically coordinating care given by VA primary care, mental health, and substance-use treatment providers in order to effectively treat patients with mental health conditions. A summary of the committee’s findings on this topic is outlined below.

- The VA has implemented models of collaborative and integrated care to improve the delivery of mental health treatment including PC-MHI, BHIP, and a continuum of care based on a stepped-care model approach.

- The VA’s PC-MHI program is a coordinated care model that connects mental and physical health, which has been shown to increase efficiency through reduced fragmentation of care and better mental health outcomes.

- Studies show that PC-MHI practice guidelines, which do not exist currently, may be especially beneficial in addressing undesirable variations in care.

- BHIP is a team-based model implemented in outpatient mental health that is intended to provide collaborative, veteran-centered, and coordinated care.

- The limited research available about BHIP shows a need to overcome barriers to team-based collaboration within this program.

- Although promising, objective data and research evidence evaluating PC-MHI and BHIP are limited.

- PC-MHI and BHIP are components of the VA’s stepped-care model for mental health, which has a goal to treat patients at the lowest appropriate intensity of care that is still likely to provide benefit, while reserving more intensive treatments for those patients who have more complex clinical presentations.

- While there is some evaluative information and data on the components of the VA’s stepped-care model for mental health care, the committee is not aware of any research that examines the effectiveness of the stepped-care model as a whole.

- Offering EBPs that have been proven effective for treating PTSD, offering time-limited services (for example, 12 PE sessions), keeping appointments short, and offering more group treatments than individual services are some strategies that the VA has employed in an attempt to deliver care more efficiently.

- It is challenging to implement these efficiencies in a way that does not compromise quality and patient-centered care.

- The VA tracks provider workforce productivity data; however, the data do not include all provider types and reviews have questioned their reliability and usefulness.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2012. AHRQ review finds evidence of the effectiveness of collaborative care interventions. Psychiatric Services 63(10):1055.

Archer, J., P. Bower, S. Gilbody, K. Lovell, D. Richards, L. Gask, C. Dickens, and P. Coventry. 2012. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 10:CD006525.

Barry, C. N., K. M. Abraham, K. R. Weaver, and N. W. Bowersox. 2016. Innovating team-based outpatient mental health care in the Veterans Health Administration: Staff-perceived benefits and challenges to pilot implementation of the Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program (BHIP). Psychological Services 13(2):148–155.

Beehler, G. P., J. S. Funderburk, P. R. King, M. Wade, and K. Possemato. 2015. Using the Primary Care Behavioral Health Provider Adherence Questionnaire (PPAQ) to identify practice patterns. Translational Behavioral Medicine 5(4):384–392.

Belsher, B. E., L. H. Jaycox, M. C. Freed, D. P. Evatt, X. Liu, L. A. Novak, D. Zatzick, R. M. Bray, and C. C. Engel. 2016. Mental health utilization patterns during a stepped, collaborative care effectiveness trial for PTSD and depression in the military health system. Medical Care 54(7):706–713.

Bohnert, K. M., P. N. Pfeiffer, B. R. Szymanski, and J. F. McCarthy. 2013. Continuation of care following an initial primary care visit with a mental health diagnosis: Differences by receipt of VHA primary care–mental health integration services. General Hospital Psychiatry 35(1):66–70.

Bohnert, K. M., R. K. Sripada, J. Mach, and J. F. McCarthy. 2016. Same-day integrated mental health care and PTSD diagnosis and treatment among VHA primary care patients with positive PTSD screens. Psychiatric Services 67(1):94–100.

Brawer, P. A., A. M. Brugh, R. P. Martielli, S. P. O’Connor, J. Mastnak, J. F. Scherrer, and T. E. Day. 2011. Enhancing entrance into PTSD treatment for post-deployment veterans through collaborative/integrative care. Translational Behavioral Medicine 1(4):609–614.

Eberhart, N. K., M. S. Dunbar, O. Bogdan, L. Xenakis, E. R. Pedersen, and T. Tanielian. 2016. The unified behavioral health center for military veterans and their families. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Engel, C. C., R. M. Bray, L. H. Jaycox, M. C. Freed, D. Zatzick, M. E. Lane, D. Brambilla, K. Rae Olmsted, R. Vandermaas-Peeler, B. Litz, T. Tanielian, B. E. Belsher, D. P. Evatt, L. A. Novak, J. Unutzer, and W. J. Katon. 2014. Implementing collaborative primary care for depression and posttraumatic stress disorder: Design and sample for a randomized trial in the U.S. military health system. Contemporary Clinical Trials 39(2):310–319.

Engel, C. C., L. H. Jaycox, M. C. Freed, R. M. Bray, D. Brambilla, D. Zatzick, B. Litz, T. Tanielian, L. A. Novak, M. E. Lane, B. E. Belsher, K. L. Olmsted, D. P. Evatt, R. Vandermaas-Peeler, J. Unutzer, and W. J. Katon. 2016. Centrally assisted collaborative telecare for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among military personnel attending primary care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 176(7):948–956.

Firozi, P. 2017. VA secretary: Less than 1 percent of calls to suicide hotline go unanswered. http://thehill.com/homenews/administration/330336-va-secretary-less-than-1-percent-of-calls-to-suicide-hotline-go (accessed May 11, 2017).

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2017. VA Health Care: Improvements Needed in Data and Monitoring of Clinical Productivity and Efficiency. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

Gerrity, M. 2016. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: Evidence update 2010–2015. New York: Milbank Memorial Fund.

Grant Thornton LLP. 2015. Assessment G (staffing/productivity/time allocation). Chicago: Grant Thornton LLP.

Heath, B., K. Reynolds, and P. W. Romero. 2013. A standard framework for levels of integrated health care. Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Health Resources and Services Administration.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2006. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions: Quality chasm series. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014. Treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military and veteran populations: Final assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Johnson-Lawrence, V., K. Zivin, B. R. Szymanski, P. N. Pfeiffer, and J. F. McCarthy. 2012. VA primary care-mental health integration: Patient characteristics and receipt of mental health services, 2008–2010. Psychiatric Services 63(11): 1137–1141.

Patel, E. L., C. Rothschild, J. Bean, R. Jill Pate, S. Jabeen, and N. Heidelberg. 2015. Working together: Interprofessional clincal care in action. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

Pomerantz, A. S., and S. L. Sayers. 2010. Primary care–mental health integration in healthcare in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Families, Systems, & Health 28(2):78–82.

RAND Corporation. 2015. Assessment B (health care capabilities). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Seal, K. H., G. Cohen, D. Bertenthal, B. E. Cohen, S. Maguen, and A. Daley. 2011. Reducing barriers to mental health and social services for Iraq and Afghanistan veterans: Outcomes of an integrated primary care clinic. Journal of General Internal Medicine 26(10):1160–1167.

Szymanski, B. R., K. M. Bohnert, K. Zivin, and J. F. McCarthy. 2012. Integrated care: Treatment initiation following positive depression screens. Journal of General Internal Medicine 28(3):346–352.

Trivedi, R. B., E. P. Post, H. Sun, A. Pomerantz, A. J. Saxon, J. D. Piette, C. Maynard, B. Arnow, I. Curtis, S. D. Fihn, and K. Nelson. 2015. Prevalence, comorbidity, and prognosis of mental health among U.S. veterans. American Journal of Public Health 105(12):2564–2569.

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2008. Uniform mental health services in VA medical centers and clinics. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2016a. Department of Veterans Affairs volume II: Medical programs and information technology programs. Congressional submission FY 2017 funding and FY 2018 advance appropriations. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2016b. Restoring trust in veterans health care: Fiscal year 2016 annual report. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2016c. VHA workforce and succession strategic plan 2016. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA. 2017. Response to committee request for information. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

Weaver, K. 2014. Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program (BHIP) team based-care. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

Zivin, K., P. N. Pfeiffer, B. R. Szymanski, M. Valenstein, E. P. Post, E. M. Miller, and J. F. McCarthy. 2010. Initiation of primary care–mental health integration programs in the VA health system: Associations with psychiatric diagnoses in primary care. Medical Care 48(9):843–851.