3

Overcoming Key Barriers

Given the disproportionate risk that the COVID-19 pandemic has posed to older adults, said Jonathan Watanabe, professor of clinical pharmacy and associate dean of assessment and quality at the University of California, Irvine, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, the pandemic has highlighted the critical importance of discovering treatments that are effective for older adults. Watanabe emphasized that the term “older adults” is not a monolith, but rather a continuum across the

life course. For example, he said, one study found that individuals over age 80 had a 20-fold increase in risk of death from COVID-19 compared with individuals age 50 to 59.

In this session of the workshop, speakers discussed the challenges of including older adults in clinical trials, given the routine presence of polypharmacy, multimorbidity, and other complications. While polypharmacy and multimorbidity can make it challenging to include older adults in clinical trials, Watanabe said, these characteristics reflect the “real-world population.” Including individuals who take multiple medications and have multiple chronic diseases will lead to findings that are more valid and relevant to the population at large.

INCLUSION/EXCLUSION CRITERIA AND TRIAL DESIGN

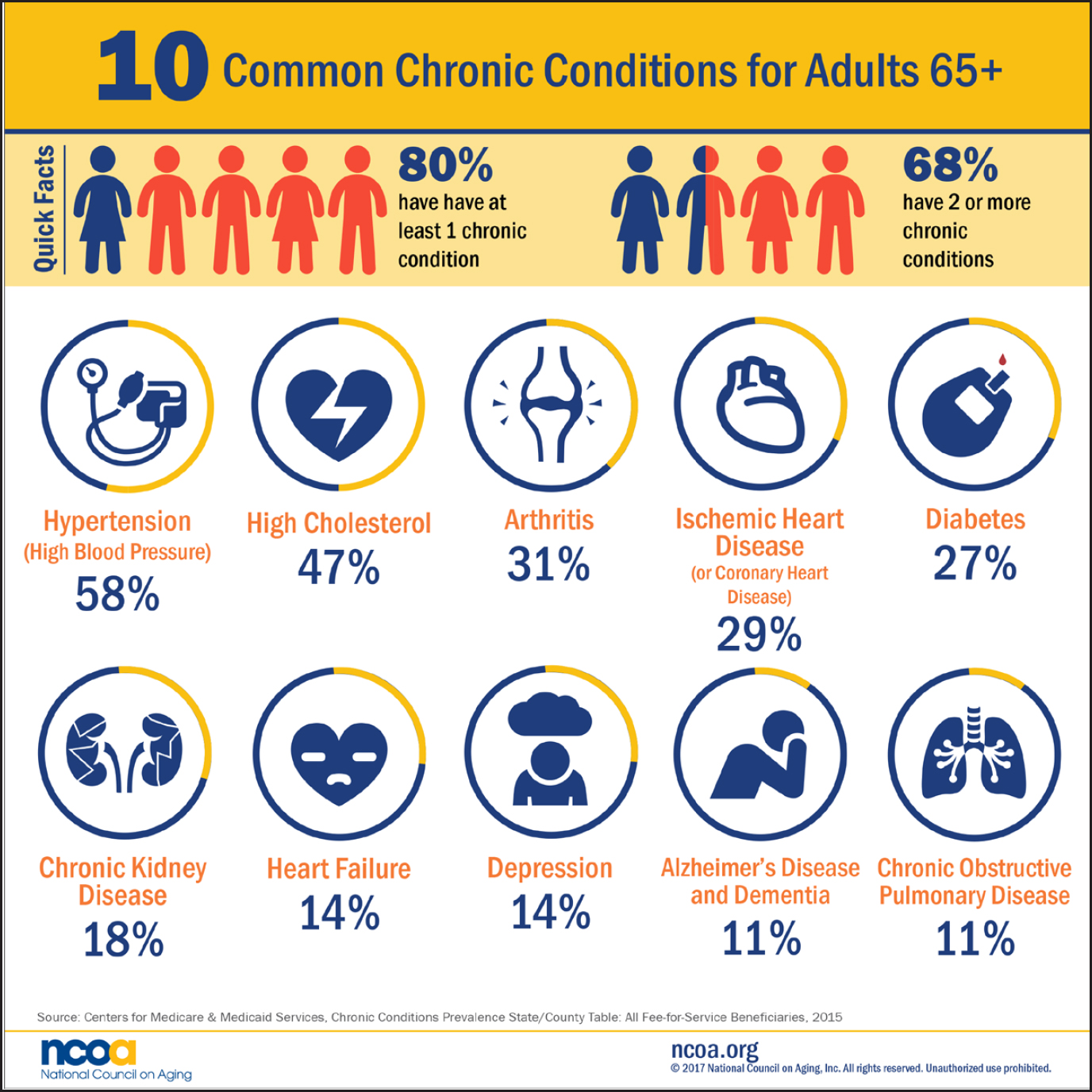

Heather Allore, professor of medicine (geriatrics) and biostatistics at Yale University, discussed some of the characteristics of older adults that make it challenging—but also critical—to include this patient population in clinical trials. Adults age 65 and older are likely to have chronic conditions, she said; 80 percent have at least one health condition while 68 percent have two or more conditions.1 The most common conditions include hypertension and high cholesterol (see Figure 3-1), and these conditions are often treated with pharmaceuticals. As a result, many older adults take multiple drugs. One study estimates that 30 percent of older adults in the United States take five or more drugs at one time (Bushardt et al., 2008). One consequence of this extensive use of pharmaceuticals is adverse drug reactions, said Allore. Adverse drug reactions in the United States are prevalent, serious, and expensive, with annual cost estimates ranging from $30 billion to $180 billion (Ernst and Grizzle, 2001; Sultana et al., 2013). Allore warned that if traditional clinical trials continue to exclude older adults, “we will continue to have unacceptably high levels of adverse drug reactions.”

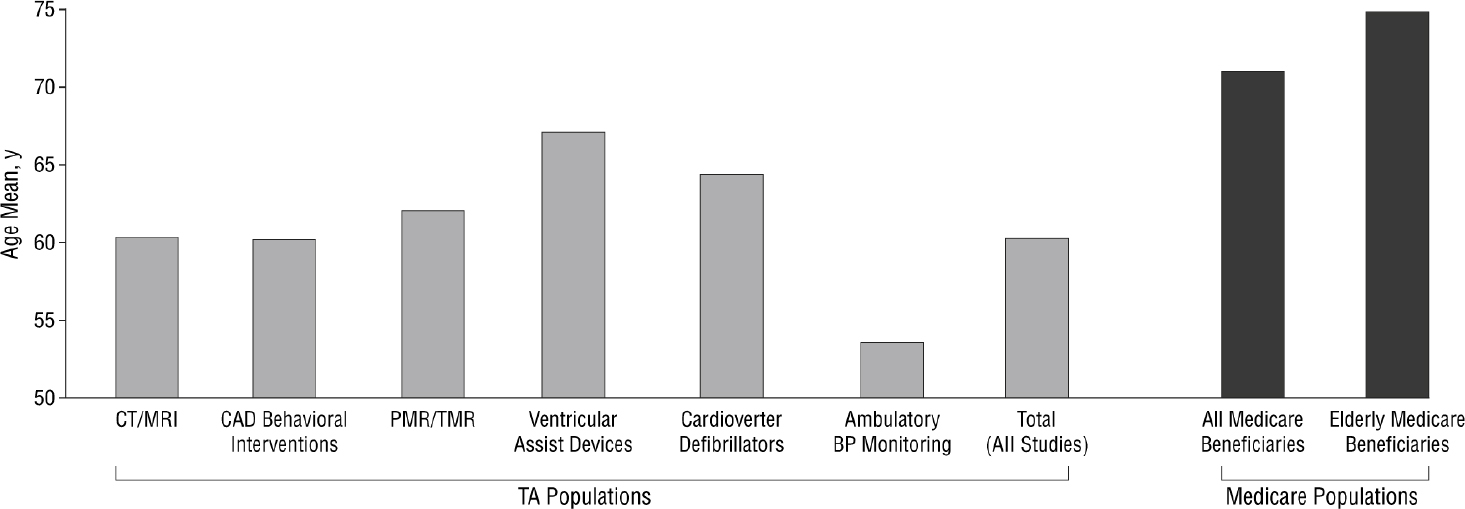

As Bernard discussed in the first session of the workshop, older adults are underrepresented in clinical trials due to age or age-related factors such as polypharmacy or multimorbidity. One concern of such under-representation, said Allore, is that financial coverage decisions are made based on these clinical trials. For example, in one cardiovascular trial study where trials that were used for Medicare coverage decisions were analyzed, it was found that the trial participants differed significantly from Medicare beneficiaries on various characteristics, including age, and that the trials rarely stratified outcomes by age, sex, or race (Dhruva and

___________________

1 Healthy Aging Facts. See https://www.ncoa.org/news/resources-for-reporters/get-thefacts/healthy-aging-facts (accessed November 11, 2020).

SOURCES: As presented by Heather Allore, August 5, 2020. Originally from the National Council on Aging, 2017 (© 2021 National Council on Aging, Inc. All Rights Reserved). See https://www.ncoa.org/blog/10-common-chronic-diseases-prevention-tips (accessed November 11, 2020).

Redberg, 2008) (see Figure 3-2). A recent analysis (Abbasi, 2019) found that older adults are regularly excluded from cancer clinical trials, and that the exclusion is not due to age alone, but rather because of comorbidities, organ dysfunction, and prior malignancies. These types of exclusion criteria, said Allore, often make older adults ineligible for participation, regardless of whether the criteria have any bearing on the treatment being studied.

There are several ways that the inclusion of older adults in clinical trials can be improved, said Allore. Funders could, for example, require strong justification for exclusion criteria, especially if those criteria make many or most older adults ineligible. Targeted federal funding could

NOTE: BP = blood pressure; CAD = coronary artery disease; CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PMR = percutaneous myocardial revascularization; TA = technology assessment; TMR = transmyocardial revascularization.

SOURCES: As presented by Heather Allore, August 5, 2020. Originally from Dhruva and Redberg, 2008.

also be used to encourage clinical trials that are designed to study older adults, particularly for conditions such as dementia that are specific to this population. Following trends when it comes to the inclusion of older adults in clinical trials could be helpful for monitoring progress and identifying barriers (Gurwitz, 2014). As a powerful incentive for increasing the participation of older people in clinical trials, Allore said, direct evidence of therapeutic benefit could be required when making national coverage determinations of service for Medicare beneficiaries.

In addition to these approaches, alternative trial designs could be considered to improve the relevance and generalizability of study results obtained from older adults. The traditional parallel group RCT has long been the gold standard for information, said Allore, but it may be time to consider alternatives such as adaptive platform designs. These study multiple interventions in a perpetual manner, in which interventions enter or leave the study platform based on predefined decision algorithms (Angus et al., 2019). These designs are currently used mostly in Phase 2 trials, said Allore, and could be embedded into clinical practice to encourage “actual patients” to enroll in trials. For example, the randomized, embedded, multifactorial adaptive platform (REMAP) is embedded in clinical practice to leverage efficiencies in trial execution, and can provide continually updated, randomized evidence of best practices (Angus, 2015). These types of designs offer numerous advantages for both drug and device development, and can help bridge the knowledge translation gap between traditional RCTs and clinical practice (Angus et al., 2019).

Another approach for improving the relevance of clinical trials, said Allore, is to use outcomes that matter to older adults. As Leipzig noted in the first session, older adults are sometimes more concerned with outcomes such as frailty and functional ability, rather than death or organ-specific endpoints. Allore presented a list of outcomes relevant to older adults that was developed by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement:

- Participation in decision making

- Autonomy and control

- Mood and emotional health

- Loneliness and isolation

- Pain

- Activities of daily living

- Frailty

- Time spent in hospital

- Overall survival

- [Caregiver] burden

- Polypharmacy

- Falls

- Place of death mapped to a three-tier, value-based health care framework (Akpan et al., 2018)

However, implementing these types of changes to improve trials—such as using alternative trial designs or measuring relevant outcomes—may be challenging for a number of reasons. Pharmaceutical companies follow the guidance of FDA and are risk-averse about including high-risk older adults, said Allore. Pharmaceutical companies also may not see any benefit to including older adults in drug trials, as these companies bear the cost of drug development but do not reap any benefit from producing more relevant data, such as lower incidence of adverse events, she explained. Additional challenges to overcome include certain FDA-required outcomes that may be disconnected from the priorities of older adults.

In summary, said Allore, “if we continue to conduct traditional clinical trials by excluding older adults … and these are our greatest users of medications, then we will continue to have unacceptably high levels of adverse drug reactions.” She highlighted the need to better inform clinical decision making for older adults, and added that many trials still do not address outcomes that matter most to older adults. Allore suggested that inclusion of older adults in clinical trials should be monitored and this information shared to improve the relevance and generalizability of study findings, and that consideration should be given to alternative trial

designs that enroll participants who better reflect the intended patient population.

ORGAN FUNCTION CRITERIA EXPANSION

As discussed previously in the workshop, Stuart M. Lichtman, medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, said that patients are being eliminated from clinical trials because of eligibility criteria that may not be clinically relevant. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends for Cancer Research developed an initiative to examine the eligibility criteria for cancer trials in an effort to broaden the criteria to make trials more representative of the population.2 Although the initiative was not specifically designed to look at older adults, said Lichtman, the fact that comorbidities are common in older adults means that they may be underrepresented in clinical trials due to these same types of eligibility criteria. Thus, he suggested, the findings and recommendations of the initiative may be relevant for increasing the participation of older adults in clinical trials.

The initiative involved a number of stakeholders, including patient advocates, clinical investigators, FDA reviewers, and biostatisticians. It initially focused primarily on six specific eligibility criteria: brain metastases, minimum age, HIV/AIDS, organ dysfunction, and prior and concurrent malignancies. The goals of the project were to challenge past assumptions and practices; to create a new culture where patients are excluded only when safety warrants; and to push for implementation of the recommendations. Part of creating a new culture of clinical trials, Lichtman said, is requiring justification of exclusion criteria and articulating the differences between trial participants and the overall patient population. He added that active discussions of eligibility criteria during trial design and meetings with FDA are an important step in this direction.

Lichtman gave a brief overview of the eligibility criteria recommendations for brain metastases, minimum age, HIV/AIDS, and prior and concurrent malignancies:

- Brain metastases: The group recommended against automatic exclusion for brain metastases, recommended that patients with treated and/or stable metastases should be routinely included in all phases of clinical trials, and recommended that eligibility for patients with active metastases should be determined on a case-by-case basis by looking at the history of disease, trial

___________________

2 Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria. See https://www.asco.org/research-guidelines/clinicaltrials/clinical-trial-eligibility-criteria (accessed November 11, 2020).

- design, drug mechanism, and potential for central nervous system interaction (Lin et al., 2017).

- Minimum age: For initial dose-finding trials, the group recommended that pediatric-specific cohorts should be included when there is strong scientific rationale, and pediatric patients should be included in later phase trials for diseases or targets that span adult and pediatric populations (Gore et al., 2017).

- HIV/AIDS: The group recommended that cancer patients with HIV should be included if they are healthy and at low risk for AIDS-related outcomes, and that HIV-related eligibility criteria should be straightforward and focus on CD4 and T-cell counts, history of AIDS-defining conditions, and status of HIV treatment. HIV should be treated using the same standards as other comorbidities, and antiretroviral therapy should be considered as a concomitant medication (Uldrick et al., 2017).

- Prior malignancies: Patients should be eligible if therapy was at least 2 years earlier and there is no evidence of disease.

- Concurrent malignancies: Patients should be eligible if they are clinically stable and do not require tumor-directed therapy (Lichtman et al., 2017).

Organ dysfunction, said Lichtman, may be used to exclude people from cancer trials; however, this exclusion is sometimes inappropriate. A traditional criterion for exclusion, for example, is a creatinine clearance of less than 60 mL/minute, yet a sizable proportion (between 20 and 45 percent) of cancer patients have this rate of creatinine clearance (Lichtman et al., 2017), which could make these patients ineligible for trials even when the drug being studied has no renal excretion. Lichtman added that using creatinine clearance for exclusion could potentially exclude older patients. He explained that abnormal creatinine clearance is less common in the breast cancer population, which skews younger, and more common in the bladder cancer population, which skews older. To increase the number of patients eligible for clinical trials, the group recommended that eligibility should be based on creatinine clearance rather than serum creatinine, and that liberal creatinine clearance (e.g., >30 mL/min) should be applied when renal excretion is not significant for the drug being studied (Lichtman et al., 2017). Furthermore, investigators should follow established dose modification strategies; Lichtman said that if these strategies for patients with renal insufficiency are implemented from the onset of treatment, patients can receive drugs safely without sacrificing efficiency. For hepatic function, Lichtman noted that current tests are inadequate, and that there is a need for close monitoring, particularly of serum bilirubin. While not age related (as in the case of renal function), monitoring hepatic

function is critical because even a small change in function can lead to significant toxicity with a drug that is hepatically metabolized.

Since making recommendations in these six areas of eligibility criteria, the group has expanded to looking at performance status, washout periods and concomitant medications, prior therapies, test intervals, and lab reference ranges. Many of these issues, he said, are important for older patients. For example, tests that are required on a frequent basis can burden the patient and caretaker, rendering the older adult patient unable to participate in the trial. Older adults make up the majority of cancer patients and experience the highest cancer mortality, so trials should be designed with their needs in mind, said Lichtman. Providers want to practice evidence-based oncology, although this approach is difficult due to a lack of evidence about cancer treatments for older patients. To gather this needed evidence, said Lichtman, clinical trials should be designed to capture the “real-world” patient population; patients from underrepresented groups should be sought out; and eligibility criteria should be in line with the goals of the trial. For example, if the drug is hepatically metabolized and in vitro studies show that the drug is not a substrate for transporters that could be inhibited by the accumulation of uremic toxins, there is no reason to have a rigid creatinine clearance threshold to make patients eligible for trial participation. Addressing these types of eligibility issues may increase the number of older patients who participate in clinical trials, ultimately increasing the evidence base for older adults.

REGULATORY CONSIDERATIONS

Most clinical trials are open to adult subjects over the age of 18, said Rajeshwari Sridhara, biostatistician contractor at FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and retired director of the Division of Biometrics V, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Why, then, are older adults often not enrolled in trials? One main reason, said Sridhara, is that clinical trials often exclude certain comorbid conditions, and it is not uncommon for older adults to have comorbid conditions. There may be other potential reasons for low enrollment, such as accessibility of clinical sites or overburden of frequent hospital visits for protocol-specified testing. Regardless of the reasons, Sridhara added that there is a need to increase enrollment of older adults in clinical trials because these patients are being treated in clinical practice and providers need to understand the risks and benefits of treatments in this population.

Sridhara shared with participants some data about drugs and therapeutic products that have been approved by FDA (2020). In 2019, 48 new molecular entities were approved for the first time for various diseases.

The studies that led to these approvals had sample sizes ranging from 56 to 11,273 patients. Participation of women in the trials ranged from 10 to 91 percent (excluding trials open only to men or women). The participation of patients age 65 and older varied from 1 percent (for treatment of a rare blood disorder) to 90 percent (for treatment of age-related macular degeneration). For 30 products, fewer than 30 percent of participants were 65 and older, and for 8 of these products, no patients were 65 and older (FDA, 2020). It should be noted, she added, that data about the participation of patients age 75 and older were not publicly available for the majority of products, suggesting a need for reporting more discrete age categories. The fact that the trials for age-related macular degeneration enrolled such a high percentage of older patients proves that “there is no inherent reason that older adults cannot or will not participate in clinical trials,” said Sridhara. Similarly, enrollment of Black patients is generally low, with 50 percent of the trials for 2019 approvals enrolling 5 percent or fewer Black patients. However, 91 percent of the patients enrolled in a study evaluating a treatment for sickle cell anemia were Black (FDA, 2020), suggesting that this population can also be adequately enrolled in trials, said Sridhara.

Sridhara presented data on cancer trials as an example of how trial populations are often not reflective of the general population. Of all people with cancer, he said, about 56 percent are 65 and older, and 29 percent are 75 and older. However, according to an analysis of 105 registrational cancer trials, only 41 percent of trial participants were 65 and older, and only 12 percent were 75 and older. Of the 17 cancer products approved by FDA in 2019, 9 included more than 30 percent of patients 65 and older, and 5 included less than 10 percent of patients less than age 65 (Singh et al., 2017). However, Sridhara noted that the five trials with fewer than 10 percent of older patients were for either very rare conditions or conditions with shortened life expectancy.

To increase participation of older adults in clinical trials, said Sridhara, investigators should consider factors including the prevalence of the disease in the older age population; access to a care facility; frequency of outcome assessment; whether outcome assessments are invasive or noninvasive; and thoughtful consideration of exclusion criteria, including toxicity and potential drug–drug interactions. During all phases of clinical trials, there are ways to include older adults without sacrificing safety or efficiency, she said. In the early phase of drug development, a small cohort of older adult patients can potentially be added to better understand safety and tolerability of the treatment. This step can be considered after safety is studied in younger adults, and will help build evidence about differential dose selection, modification, and drug–drug interaction in the older population. In addition, including older adults at this stage

will allow for evaluation of the feasibility of outcome assessments. If the treatment is deemed safe and feasible, investigators and drug sponsors will be more willing and likely to enroll older patients into trials, she said. In late-stage studies different trial designs can be used to include older adults (e.g., using single-arm cohorts of older high-risk patients). After products are approved, older adults can also be studied using postmarketing registries and other methods of collecting real-world data.

Sridhara provided some examples of trial design options, and described some of the benefits and drawbacks. In an RCT, a restricted homogeneous population is usually enrolled so that any treatment effect can be evaluated with a minimum number of patients. If there is more variability in the population—as is the case for participants of varying ages and multiple comorbidities—it becomes more difficult to show a treatment effect. However, it is possible to include the restricted homogeneous population as well as an older high-risk population. This can be accomplished by hierarchical testing first in the restricted population and then in the high-risk population. Another approach, said Sridhara, is to conduct simultaneous studies by using an RCT in the restricted population and a single-arm cohort for the high-risk population. In this approach, each population is analyzed separately, and only descriptive statistics are used to report the results from the single-arm cohort. When designing these types of trials, key considerations include determining what comorbidities, drug–drug interactions, and levels of toxicity are acceptable; what proportion of patients in the older high-risk population should be included; whether hierarchical testing is feasible; and how to evaluate safety in the high-risk population. Sridhara noted that when using a single-arm cohort, it can be difficult to interpret toxic events without a control arm.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

“Why do people enroll in trials?” asked Jason Karlawish, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. The decision to enroll, he said, is a personal one that is based on preferences and values. Multiple studies have shown that the decision to enroll is a multi-attribute decision that balances the three broad categories of trust, altruism, and expectation of benefit (Comis et al., 2009; Locock and Smith, 2010; Mueller, 2004). Trust relates to multiple areas, including trust in the research enterprise or a belief that research is a social good, trust in the individual researcher, trust in the institution conducting the research, and trust in the sponsor. Altruism is a belief in benefiting others, such as people with the same condition; one’s children or grandchildren; or humanity in general. Expectation of benefit, said Karlawish, could include

health benefits (or at least no harm), financial benefit, or simply enjoying the process of participating in the trial.

These components—trust, altruism, and benefit—have been studied using a tool called the Research Attitudes Questionnaire (Rubright et al., 2011). The questionnaire asks people to rate their level of agreement with seven statements:

- I have a positive view about medical research in general.

- Medical researchers can be trusted to protect the interests of people who take part in their research studies.

- We all have some responsibility to help others by volunteering for medical research.

- Society needs to devote more resources to medical research.

- Participating in medical research is generally safe.

- If I volunteer for medical research, I know my personal information will be kept private and confidential.

- Medical research will find cures for many major diseases during my lifetime.

Respondent’s answers are compiled into a composite score, and this score is considered to be a strong predictor of willingness to participate in clinical trials. Karlawish suggested that evidence gleaned from the use of the Research Attitudes Questionnaire further strengthens the theory that attitudes of trust, altruism, and expectation of benefit are what drive people to make the decision to enroll in a specific study.

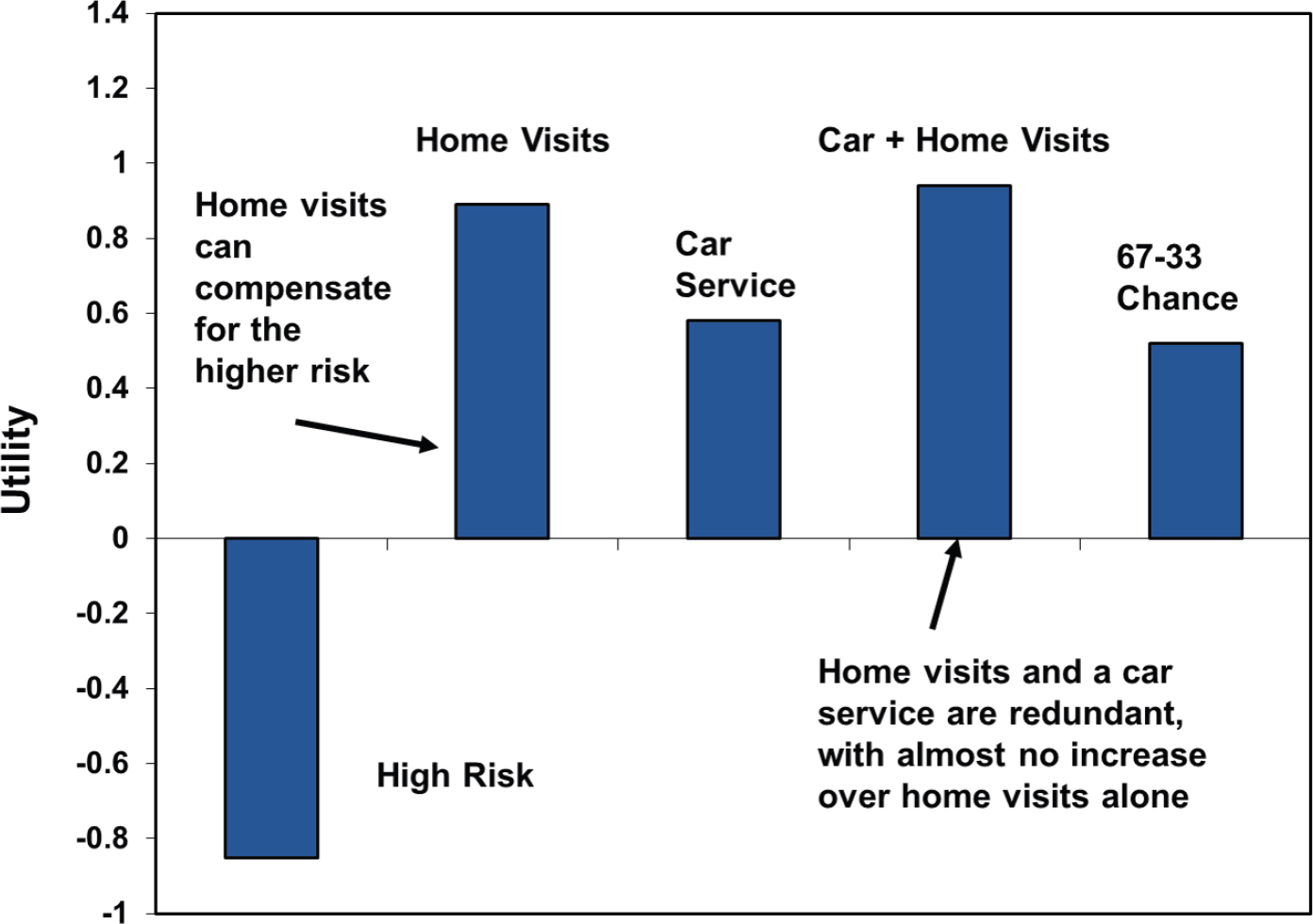

The question, then, is whether a clinical trial can be designed in a way that increases people’s willingness to participate. Karlawish noted that “research is work … that is why we pay people to be in studies.” Participating in a study takes time and effort to travel to the study site and undergo testing or procedures, he said. Because of physical and cognitive impairments, older adults may have difficulty with these forms of work and may need additional help. To overcome these types of barriers and increase willingness to participate, clinical trials could be redesigned to address factors such as location of study visits, transportation, potential risk, and chance of receiving the experimental treatment. Karlawish and his colleagues (2008) examined these variables by asking dementia caregivers to rank various scenarios according to whether they “definitely would participate” or “definitely would not participate” in a hypothetical trial. Participants in the study were given cards with various combinations of trial attributes, including (1) 10 visits at the trial site versus 2 visits at the trial site and 8 at home; (2) providing a car service versus having a caregiver who is responsible for transportation; and (3) varying degrees of risk and probabilities of receiving the experimental treatment. By com-

paring the rankings of various scenarios, the researchers identified how manipulating certain attributes of a clinical trial could change someone’s willingness to participate. For example, it was found that while caregivers were less likely to participate if the trial was higher risk, this drawback could be offset by offering home visits rather than requiring travel to a clinical site (see Figure 3-3). Furthermore, the willingness to participate in a trial was doubled with the use of home visits and when participants had a greater chance at receiving the research drug; reducing the risk of the study drug nearly tripled the willingness to participate. Karlawish said that reducing the burden of travel was especially valuable to caregivers with sicker patients, particularly those with functional losses and behavior issues.

In closing, Karlawish offered some potential approaches for increasing the willingness and ability of older adults to participate in clinical trials. He said that there is a need to “educate and empower people about the value of research” to capitalize on older adults’ tendency toward altruism. As older adults tend to focus more on the present, Karlawish noted that

NOTE: A positive value indicates that the factor is associated with increased willingness to participate and a negative value indicates a factor is associated with a decreased willingness to participate.

SOURCES: As presented by Jason Karlawish, August 5, 2020. Originally from Karlawish et al., 2008.

framing research participation as a pleasant, “feel-good” activity may be beneficial. Karlawish added that investigators should also think carefully about the work that is being asked of participants in a trial, such as how far and how frequently participants are being asked to travel. Investigators could additionally consider modifying some of these attributes (e.g., by offering home visits) to increase willingness to participate. Finally, the role of the caregiver deserves greater attention; whether the caregiver is a spouse, family member, or friend, caregivers take on a lot of the work of participating in a trial, and investigators should consider compensating them for this work, said Karlawish.

DISCUSSION

Watanabe led the presenters in a panel discussion, covering topics including the gap between the study population and user population; barriers for older adults; postmarket research; and target populations for trials.

Gap Between Study Population and User Population

Watanabe opened by expressing his astonishment with the data that Allore presented regarding the age differences between Medicare recipients and study participants (see Figure 2-2). Watanabe considered whether guidelines could be developed to better encourage enrollment of trial participants that more closely mirror the eventual users of the product. Allore agreed that this was an interesting idea, and suggested that insurers would be particularly interested in evidence that shows whether a product would be efficacious in the patient population. Sridhara added that when FDA approves a product, it is approved for all adults; payers will cover the product regardless of a patient’s age. However, she added, due to the lack of evidence about use in older adults, the treating physician still may not have all the information needed to safely and effectively treat a patient.

Barriers to Enrolling Older Adults in Trials

Watanabe asked presenters for their thoughts on how to increase trial participation of older adults, particularly those with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. He noted that there is a need to study this population of patients, but notable challenges accompany these patients’ enrollment. Karlawish began by suggesting that future research might study these patients and determine what is keeping them out of trials. Older adults who qualify as “frail,” for example, could be further assessed in their

attitudes about trust, altruism, and benefits; perceived barriers could also be measured, and frail older adult input could be solicited on how those barriers might be overcome. Sridhara noted that additional lessons could be learned from trials that have enrolled large percentages of older adults, such as trials related to age-related macular degeneration or other age-related conditions. Examining the design of these trials and the characteristics of participants could reveal approaches for increasing enrollment of older adults in other trials. Lichtman stated that several cancer trials that have been successful at enrolling older adults did not use placebo randomization, but rather grouped participants according to the treatment preferences of physicians and patients. Allore added that there are analytic approaches that can be used to analyze this type of design, and that there may be a need to move away from the traditional parallel group RCT. In addition to these considerations, said Lichtman, the logistical and financial barriers (e.g., driving long distances to a trial site) must be addressed for older patients to participate in trials.

Postmarket Research

One audience member asked the presenters about the feasibility of requiring postmarket research on older adults. Lichtman responded that while he has heard such a suggestion recurrently proposed over the course of the past 20–30 years, he has not yet witnessed the implementation of such a requirement. He added that although people typically talk about carrots and sticks for encouraging change, the “only way it’s going to happen is if you have a carrot and a bomb.” Allore said that pharmaceutical companies are under immense pressure and are doing “really good work,” but bringing a drug to market is expensive, and companies do not bear the costs of adverse events. The stakeholders who have the most incentive to discover whether drugs are safe and effective in older adults, she said, are insurers and taxpayers because these are the entities who ultimately bear the costs. Lichtman countered that some of these drugs cost thousands of dollars per month, and that enrolling 50 or 100 patients in a postmarketing study would be well worth the investment for a pharmaceutical company.

Target Populations for Trials

Given that drugs are often approved based on studies in relatively narrow populations, Watanabe asked, how should researchers decide which additional trials to conduct? What are the considerations for determining which populations to target? Karlawish noted that there are two avenues to answering this question. One avenue is scientific, and consid-

ers the specific disease and treatment and how it may vary based on age or other characteristics. The second avenue is a process or political matter, he said, and revolves around who the gatekeepers are for deciding whether trial populations are appropriate. Karlawish noted that while there are many stakeholders in the clinical trial space—including pharmaceutical companies, FDA, NIH, payers, providers, and patients—each of these stakeholders has their own perspective and priorities. There is not currently an entity or institution that can look at the considerations that have been discussed in this session and determine whether the populations enrolled in clinical trials are appropriate, he said.

This page intentionally left blank.