4

Training New Recruits and Current Faculty to Be Effective Educators (Step 3)

HIGHLIGHTS

- The content, context, and methods used in education are never neutral, and there are always power dynamics at play. (Cohen Konrad)

- Instructors have a responsibility to create an environment where learners feel safe to make mistakes, propose alternative views, and have honest discussion. (Cohen Konrad)

- Using a framework for education can encourage self-awareness, restoration, and growth. (Pardue)

CONSCIOUS INSTRUCTION: AWARENESS, RESTORATION, AND GROWTH IN KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

Shelley Cohen Konrad, Karen Pardue, and Kris Hall, University of New England

The third step of faculty development, said Shelley Cohen Konrad, director of the University of New England’s (UNE’s) Center for Excellence in Collaborative Education (CECE), is formal education or training that takes places in the classroom or workplace. Cohen Konrad, along with her colleagues from UNE, Karen Pardue, dean of Westbrook College of Health Professions, and Kris Hall, program manager of CECE, developed a framework called “conscious instruction.” This framework, said Cohen

Konrad, calls attention to the “what, how, and why of education” and the choices that are made in every aspect of knowledge transfer.

Before presenting the framework, Pardue introduced workshop participants to some key terms used in their presentation (see Box 4-1), and Hall asked participants to reflect on the type of educator that they aspire to be. Responses, submitted through a computer polling app, included

- Engaging

- Humble

- Impactful

- Role model

- Innovative

- Norm shattering

- Connected to practice

- Quietly influencing

To explore the different dimensions of the conscious instruction framework, Cohen Konrad showed participants a video case study, which was created by an interprofessional team for students at UNE. The video

centered on a 31-year-old woman with a variety of health concerns and barriers to care.1 A full transcript of the video is presented in Box 4-2.

Cohen Konrad emphasized the importance of using case studies that learners can relate to in terms of culture and geography, and that resemble patients that the learners are likely to serve in their communities. However, she said, it is also important to be careful about perpetuating stereotypes and assumptions; using case studies can open up the discussion and allow instructors and learners to address these stereotypes. She said that the use of video can be extremely helpful because it gives learners a “visceral sense” of the client, and the ability to see the client in action. She noted, in response to a participant’s question, that captions or transcripts can be used for videos in order to be accessible to those with hearing impairments. The discussion that followed is presented in Box 4-3.

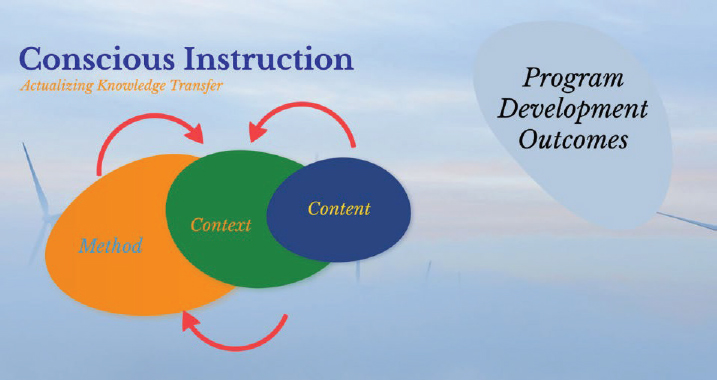

The conscious instruction framework (see Figure 4-1), said Cohen Konrad, is multidimensional and intersectional, and it is designed “to hold us accountable as educators to teach and to create an environment for

___________________

1 Hall, K. July 22, 2020. Pat Chalmers case study. UNE IPEC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mVjii51ODzk (accessed November 28, 2020).

learning.” The framework includes three domains: content, context, and method. Content—the knowledge that is transferred—is “never neutral,” said Cohen Konrad. There is a mythology, she said, that health education is based on facts and is on “neutral ground.” To the contrary, nothing in education—content, context, or methods—is ever neutral. Content includes

- What definitions are used?

- Where does the evidence come from?

- What reflexive knowledge is being formally communicated?

- How does the instructor’s own experience inform the teaching?

- What is the instructor’s level of comfort with the material?

SOURCE: Presented by Cohen Konrad, Pardue, and Hall, August 11, 2020.

Cohen Konrad went on to describe how effective teaching requires intellectual and emotional engagement risking exhaustion, disengagement, and burnout. It is the role of faculty and trainers to impart an understanding of self-awareness among their educators, she said, but according to Shealy et al. (2019), the trainers need to be self-aware and confident themselves before they can train others in the area of self-awareness. Pardue picked up on this notion saying that instructors have a responsibility to be self-reflective in their teaching, and to continuously assess and adapt their practice and the content based on inputs such as student, peer, or supervisor feedback, video recordings, and personal teaching notes. “Reflective teachers assume responsibility for continuously assessing the content … and actively considering the answer to the question, ‘How am I doing in my teaching practice?’”

The next area Pardue covered involved the context in which education is delivered to, and received by, faculty and others. Context is influenced by multiple factors: by select critical and sociological theories, by what is included and excluded from the narrative, by implicit and explicit bias and assumptions, and by social determinants and individual circumstances. Considerations of context involve deliberate examination of power structures and decision-making practices, challenging the status quo, and giving voice to individuals and populations commonly not heard. Pardue encouraged participants to think back to the video case study and consider what unique circumstances and professional biases affected knowledge transfer in that example.

In considering the third area, how knowledge is transferred (i.e., methods), Cohen Konrad noted the role of instructors. Instructors, said Cohen Konrad, are role models; learners watch what they do and how they do it. How an instructor teaches is the method, and is as important as what he or she teaches. Cohen Konrad said that instructors are on the “frontline of psychological safety,” and that when instructors are curious, authentic, open, and willing to acknowledge biases and missteps, they encourage learners to do the same. Health professional education involves difficult conversations about issues such as race, justice, and sexual orientation, said Cohen Konrad, and instructors have a responsibility to create an environment where learners feel safe to make mistakes, propose alternative views, and have honest discussions.

Building on Cohen Konrad’s remarks, Pardue described affective learning. Affective learning considers the attitudes and values of a learner, with the goal of achieving a demonstrable change in a person’s behavior. This type of teaching requires enormous creativity and use of multiple modalities, such as a video that draws the learner in visually and auditorily. A workshop participant asked how to assess whether methods such as video are useful. Cohen Konrad responded saying they use rapid cycle evaluation to gather input from learners about what methods are effective. At UNE, they also look at whether learners are achieving the goal competencies.

Power Dynamics

Before leaving the methods domain, Cohen Konrad acknowledged the need to discuss power. No matter the instructional method, she said, there are natural power dynamics. Instructors select the content, select the method, do the evaluating, and determine “whose story is told and whose story isn’t told.” Instructors decide whether to “radically listen and respond,” or to instead cut off discussions that may be uncomfortable. Instructors need to engage with power dynamics, acknowledge power differentials, and engage students in these conversations, she said. Cohen Konrad suggested one way to flip this dynamic is to engage local communities in developing content, context, and method. For example, UNE worked with members of immigrant and refugee populations in Portland, Maine, to develop a course called “Empowering Cultural Education.” The course was developed, taught, and evaluated by the community, along with an evaluation tool for measuring cultural competence and cultural humility. Cohen Konrad said that it was a “very critical learning experience” about teaching with populations, rather than about them.

Self-Awareness, Restoration, and Growth

The conscious instruction framework, said Cohen Konrad, also includes self-awareness, restoration, and growth as beneficial outcomes of using the model. Teaching, according to Bodenheimer and Shuster (2020), involves strenuous emotional labor and leaves instructors vulnerable to burnout and intellectual fatigue. A conscious instruction practice can help reduce burnout and increase the likelihood of instructor satisfaction, Cohen Konrad noted. Self-awareness, said Pardue, is a deliberate, conscious knowledge of ourselves, and involves focused attention and honesty in exploring the “why” of ideas, thoughts and actions. It provides faculty an opportunity to be objectively curious about themselves. Dedicating time and deliberate attention to self-awareness, said Pardue, leads to instructor restoration. Restoration is “the experience of feeling renewed and healed.” Restoration liberates faculty, and it sparks creativity and new connections. A restorative state is reinvigorating, and it can serve as a buffer to the demanding, challenging work of teaching, she added. Finally, growth includes advancing our own knowledge, professional development, and instructional inspiration.

In many respects, Pardue noted, the conscious instruction framework parallels the quadruple aim of health care (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014). These frameworks focus on improving quality (of education or care), improving the experience (of a learner or a patient), and assuring well-being (of instructors or health care providers). Pardue further noted that both frameworks can also reduce costs—if faculty are satisfied and reinvigorated with their work, they are less likely to leave.

Skilling Me Softly

In the closing minutes of the session, Pardue introduced participants to an exercise called “Skilling Me Softly” where she asked the participants to reflect back on the Pat case study (see Box 4-2). She then presented a list of desired qualities and skills for health care workers (see Box 4-4) and invited participants to think about how they would use the video case study to transfer knowledge of these assets. Pardue encouraged participants to continue thinking about how they would use the video, their comfort level in doing so, and what barriers might exist to achieving success (i.e., demonstrating acquisition of the desired skill or quality).

REFERENCES

Bodenheimer, G., and S. M. Shuster. 2020. Emotional labour, teaching and burnout: Investigating complex relationships. Educational Research 62(1):63–76.

Bodenheimer, T., and C. Sinsky. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine 12(6):573–576.

Brown, B. 2018. Dare to lead: Brave work. Tough conversations. Whole hearts. New York: Penguin Random House.

Edmondson, A. C. 1999. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly 44(2):350–383.

Shealy, S. C., C. L. Worrall, J. L. Baker, A. D. Grant, P. H. Fabel, C. M. Walker, B. Ziegler, and W. D. Maxwell. 2019. Assessment of a faculty and preceptor development intervention to foster self-awareness and self-confidence. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 83(7):6920. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe6920.

Tobin, K. 2009. Tuning into others’ voices: Radical listening, learning from difference, and escaping oppression. Cultural Studies of Science Education 4:505–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-009-9218-1.