Part II

|

| This page in the original is blank. |

6 New Military Missions

Organizations must adapt to environmental change. A prime instance is when their central purposes or missions are dramatically altered. The other chapters of this book highlight the challenges faced by organizations when they undergo a significant change in their missions, whether the change is the addition of new missions, the abandonment of old missions, or the modification of existing ones.

Unlike the previous chapters, which review the literature on organizations broadly and draw conclusions pertaining generally to many types of organizations, this chapter and the next concentrate attention on the case of a single, complex organization—the U.S. Army—as it undergoes fundamental changes in its missions. Although the arguments developed apply as well to other types of organizations, we are focusing here on the particular circumstances of the Army. Appendix A provides a brief discussion of the ways in which military organizations differ from other organizational forms.

Changing Missions In A Post-Cold War Era

Although the basic purpose of U.S. Army—the successful waging of land warfare—has not changed, its missions have broadened for it to function in the post-cold war world. The unforeseen and precipitous end of the cold war and the attendant reordering of international society have altered some of the basic missions, training, and orientations undertaken by that organization (McCalla, 1994). The first major change is the shift in focus from one central enemy (the Soviet Union) to a potential multiplicity of enemies or no enemy at all. With the breakup of the Soviet Union, the

United States military no longer can consider actions in a bipolar setting, but may face many different enemies consisting of many states or even subnational groups; some of its missions may even render traditional conceptions of enemy and ally irrelevant. Second, the "new world order" may place less significance on nuclear weapons and traditional conventional military firepower. In many new missions, such heavy weaponry is inappropriate or even counterproductive to the goals that must be achieved; restraint of military force may be necessary, replacing traditional notions of battlefield superiority.

Third, the fixed deterrent deployment of the U.S. Army, so common in Europe, Korea, and elsewhere during the cold war, must be transformed to deal with quickly emerging crises in many parts of the world. The need for the development and refinement in the military of smaller-sized rapid deployment forces has accelerated with the diminution of the Soviet/Russian threat and the emergence of new hot spots in Somalia, Bosnia, and elsewhere; the Army must now adopt more flexible, ad hoc deployment strategies. Fourth, the activities that the Army may be called on to perform have increased both in number and scope.

Finally, the end of the cold war has led to the creation of more multinational military operations. Previously, the U.S. Army was involved in joint operations only with close allies. Now the Army faces the prospect of participating in actions that (1) may involve a large number of different state actors, not all of whom may support American goals, (2) may not include well-defined procedures for coordination, and (3) may involve United Nations (UN) or foreign command over its forces. (This change was officially recognized in President Clinton's National Security Strategy released by the White House in February 1995.) Many of the benefits and problems of interorganizational cooperation noted in the previous chapter are thus directly applicable to the U.S. Army in performing its new missions. However, these missions differ from the kinds of joint ventures and mergers discussed in Chapter 5. They are almost always temporary, imposed on the Army without the organization's consent, and involve a variety of governmental and nongovernmental organizations whose tasks overlap rather than complement one another, as in the cases of corporate collaboration described earlier. Here we consider the kinds of coordination issues that occur in the context of the new Army missions.

In the post-cold war era, the U.S. Army has had to adapt to a broadened and more extensive set of missions and requirements. This chapter describes this new range of missions and develops a typology useful for analyzing the similarities and differences among them. In light of that analysis, we go on in the next chapter to identify the skills needed for the different missions.

Classifying And Comparing Missions

Beyond its traditional roles in the defense of the United States and its national interests, the U.S. Army has been or may be called on to perform a variety of other missions. The term peacekeeping has been popularly used to designate a wide range of phenomena, often improperly referring to any international effort involving an operational component to promote the termination of armed conflict or the resolution of long-standing disputes. In the interest of conceptual clarity, we offer the following taxonomy of different missions qualifying as operations other than war, which is the designation that the military uses for nontraditional operations and includes peacekeeping operations as well as missions that fall well outside that realm. The taxonomy does not include all possible missions (for such a list might be infinite), but rather represents those missions that the Army or other foreign militaries have been called on to perform recently or historically, are on the agenda for possible peacekeeping missions by the United Nations, or have received serious consideration in American and international policy-making circles. In providing this taxonomy as a prelude to an analysis of appropriate training and skills, we are not offering a judgment about the wisdom or viability of these missions, but only recognize that such missions will be the product of government decisions and preparations should proceed as if they might be implemented.

The categories below are also not mutually exclusive, since a given military operation may include more than one of the missions outlined, either simultaneously or sequentially (there may be instances, however, in which the missions are fundamentally incompatible with one another). Such mixing of missions may not even be designed or anticipated at the outset or even during the course of a mission. Mission change and adaptation may occur very rapidly on a micro level during the performance of a specific operation, much as it does at the macro level when fundamental changes in missions can occur.

A Taxonomy of Operations Other than War

- Traditional peacekeeping is the stationing of neutral, lightly armed troops with the permission of the host state(s) as an interposition force following a cease-fire to separate combatants and promote an environment suitable for conflict resolution. Traditional UN peacekeeping troops were deployed in Cyprus beginning in 1964 and southern Lebanon starting in 1978 (Diehl, 1994).

- Observation consists of the deployment of a small number of unarmed, neutral personnel with the consent of the host state to collect information and monitor activities (cease-fire, human rights, etc.) in the deployment

- area, sometimes following a cease-fire or other agreement (Wainhouse, 1966). The UN observer mission in the Middle East (UNTSO), first deployed in 1948, is an example.

- Collective enforcement is a large-scale military operation designed to defend the victims of international aggression and restore peace and security by the defeat of aggressor state forces (Mackinlay, 1990; Mackinlay and Chopra, 1992; Downs, 1994). The multinational operations in Kuwait in 1991 and Korea in the 1950s fit this profile; so too would a "collective security" operation, as envisioned by the UN Charter, carried out by an international army.

- Election supervision consists of observation and monitoring of a cease-fire, disarmament, and a democratic election following a peace agreement among previously warring internal groups; this function may also include the assistance of local security forces (Beigbeder, 1994). UN operations in Namibia in the late 1980s and Cambodia in the early 1990s are examples.

- Humanitarian assistance during conflict involves the transportation and distribution of life-sustaining food and medical supplies, in coordination with local and international nongovernmental organizations, to threatened populations during a civil or interstate war (Minear and Weiss, 1993; Natsios, 1994; U.S. Department of the Army, 1994). Operations in Somalia and Bosnia during the 1990s are examples.

- Disaster relief involves the transportation and distribution of food and medical supplies as well as the rebuilding of infrastructure and maintenance of basic services following a natural disaster (Gordenker and Weiss, 1991; Cuny, 1991). The U.S. Army relief operation after Hurricane Andrew in 1992 is an example.

- State/nation building includes the restoration of law and order in the absence of government authority, the reconstruction of infrastructure and security forces, and facilitation of the transfer of power from the interim authority to an indigenous government (Kumar, 1995; U.S. Department of the Army, 1994; Boutros-Ghali, 1992; Cox, 1993). The United Nations carried out some of these functions in the Congo in the early 1960s, but it was unable to do so in Somalia after the deployment of forces in the early 1990s. The U.S. Marine involvement in the Caribbean during 1920-1930 is another example of nation building.

- Pacification consists of quelling civil disturbances, defeating local armed groups, forcibly separating belligerents, and maintaining law and order in an interstate war, civil war, or domestic riot, especially in the face of significant loss of life, human rights abuses, or destruction of property (U.S. Department of the Army, 1994). The international community was reluctant to take this kind of action after the start of the Bosnian conflict in the early 1990s, despite the high level of casualties and ethnic-cleansing campaigns.

- Preventive deployment consists of stationing troops between two combatants to deter the onset or prevent the spread of war (Mackinlay and Chopra, 1992; Diehl and Kumar, 1991; Urquhart, 1990; U.S. Department of the Army, 1994). The UN-sponsored troops in Macedonia, deployed in the early 1990s to deter the spread of war in the former Yugoslavia, are examples of this type of nontraditional use of military force.

- Arms control verification includes the inspection of military facilities, supervision of troop withdrawals, and all activities normally handled by national authorities and technical means as a part of an arms control agreement (Krepon and Tracey, 1990; Mandell, 1987; Jurado and Diehl, 1994). Multinational peacekeeping troops performed some of these functions in the Sinai operation that followed the 1979 Egyptian-Israel peace agreements.

- Protective services includes the establishment of safe havens, "no fly" zones, and guaranteed rights of passage for the purpose of protecting or denying hostile access to threatened civilian populations or areas of a state, often without the permission of that state (U.S. Department of the Army, 1994). International actions in the 1990s to protect the Kurds in Iraq (Operation Provide Comfort) and the Muslims in Bosnia are consistent with this purpose.

- Drug eradication consists of the destruction of narcotic-producing vegetation and processing facilities and the monitoring of international transit points for narcotics trafficking; it may or may not involve coordination with the governments of narcotics-exporting states (Rikhye, 1991; U.S. President, 1992). Some U.S. efforts in concert with the Colombian government over several decades are related to this nontraditional military mission.

- Antiterrorism involves using the military to strengthen facility security and assist in training programs, replacing or supplementing traditional civil or paramilitary forces in these roles. Some actions may even include counterterrorism roles, such as assisting in hostage rescue or negotiation (Diehl, 1994; Rikhye, 1991). The Israeli military performs many of these functions.

- Intervention in support of democracy is a military operation intended to overthrow existing leaders and to support freely elected government officials or an operation intended to protect extant and threatened democratic governments; activities may include military action against anti-democratic forces and assistance in law, order, and support services to democratic authorities. The United States invasion of Panama in the 1980s and the 1994 intervention in Haiti (at least until General Cedras agreed to relinquish power) are illustrative of such missions.

- Sanctions enforcement is the use of military troops (air, sea, and land) to guard transit points, intercept contraband (e.g., arms, trade), or punish a state for transgressions (e.g., human rights abuses) defined by the

- international community or national governments in their imposition of sanctions (U.S. Department of the Army, 1994). A blockade of North Korea or other nuclear weapons-seeking states to punish them for violations of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty would be an example. The U.S. blockade of Cuba in 1962 is another example.

- Aid to domestic, civilian populations consists of the use of military forces in their native country for enhancing the well-being of the population in several areas (Nunn, 1993):

- Human capital development is assistance in the improvement of educational, personal, and vocational skills among different segments of society. The U.S. Civilian Conservation Corps' program during the 1930s is an example. The proposed National Guard Youth Corps and the YESS program in Michigan are other examples.

- Public health assistance is the assistance of public health authorities in meeting emergency needs and chronic problems associated with the health of the population. The Military Assistance to Safety and Traffic Program already incorporates some of this mission and is available in several states.

- Rehabilitation of infrastructure is the restoration and construction of public facilities (e.g., roads, schools, housing). Although a foreign example, Operation Provide Comfort in Iraq provided road and housing construction similar to what might be done domestically.

- Firefighting consists of the use of military troops to support civilian efforts in controlling forest fires and wildfires. The 1994 deployment of U.S. troops to fight fires in the Pacific Northwest is an example.

This taxonomy provides an initial classification of operations other than war by reference to the purposes of these 16 missions. In order to develop efficient training programs and strategic planning, there have been attempts to classify these missions further along several dimensions, identifying similarities across types. One method has been to consider the timing of the intervention vis-à-vis the stage of armed conflict (Thurman, 1992); operations are classified according to whether they are deployed before hostilities occur (such as some forms of preventive deployment), during low-intensity conflict, during full-scale war, or following armed conflict (such as election supervision). Another method (Mackinlay and Chopra, 1992) is to arrange operations according to the level of risk (generally the intensity of conflict) and the military assets necessary for the operations; observation and enforcement missions generally represent the ends of this continuum. Still other classifications implicitly combine mission function, timing, and level of coercion to derive the popularly used categories of peacekeeping, peacemaking, peace building, and peace enforcement (although the actual meaning

of these terms varies widely) (Boutros-Ghali, 1992; U.S. Department of the Army, 1994).

Such categorizations can be misleading because of their imprecision; they are often not useful because they lump together seemingly disparate missions, which involve very different characteristics, actions, and training. As an alternative to the traditional continuum of peace operations, we offer a new method of classification based on characteristics drawn from the academic literature on international conflict management.

Similarities and Dissimilarities Among Missions

The classification developed by the committee describes each mission in terms of 11 contextual characteristics that are related to its deployment (Table 6-1). These characteristics vary considerably in the degree of control that military planners and commanders can exercise over conditions. Some characteristics are inherent in the operation and determined by political decisions or extant factors; these include the roles played by the military force, the extent to which national constituencies accept the costs and possible losses incurred by the mission, and the ease with which success can be judged. Other characteristics are subject to greater manipulation or modification by the military. Some involve greater military influence, such as whether procedures for the mission are clear. Others can be only partly influenced by the military themselves, such as the ease of exist and the likelihood that the mission expands beyond expectations, referred to as ''mission creep." Certain contextual factors may be relatively fixed at the outset, such as the clarity of the relationship with the host country, but might change over time as a result of the strategy and behavior of the military

TABLE 6-1 Contextual Characteristics of Missions

|

Characteristic |

Categories |

|

Role of peacekeeper |

Primary, mixed, or third-party |

|

Clarity of relationships with host country |

Clear, clear on some tasks but vague on others, or vague |

|

Clarity of procedures |

Clear, fluid, or vague |

|

Clarity of goals and desired outcomes |

Clear, somewhat clear, or vague |

|

Conflict management process |

Distributive, mixed, or integrative |

|

Level of control over conflict |

Much, moderate, or little |

|

Ease of exit from mission |

Easy, moderate, or difficult |

|

Possibility of mission creep |

High, moderate, or low |

|

Assessment of mission success |

Easy, moderate, or difficult |

|

Tolerance of costs by constituencies |

Low, moderate, or high |

|

Prior experience for Army |

Much, some, or little/none |

force. In addition to these contextual characteristics, the missions can also be described in terms of the Army's experience with this or a similar kind of operation.

Mission Profiles

By describing the missions in terms of the characteristics listed in the table, we can construct a profile of each mission. For example, traditional peacekeeping may be described as follows: the soldier's role is that of third party, relationships with the host country are clear on some tasks but vague on others, procedures are fluid, goals are clear in the short term but vague in the long-term, the process is primarily integrative, soldier control is relatively low, existing from the operation is difficult, the chances for mission creep are moderate, the assessment of success is moderately difficult, constituencies have little tolerance for costs, and, with regard to traditional Army experience, there are few analogues.

We note that a number of other characteristics, which do not affect the mission profiles, are also certainly relevant to military planning and may impact the kinds and degree of training required for a given mission; many of these characteristics are context specific and cut across different mission types. They include the likely degree of interaction anticipated with the local population, the dispersion of forces and the relative autonomy granted different parts of the operation, the physical conditions (amenities, level of privacy, facilities) in the area of deployment, the degree and type of communication access, logistical dependence, clarity of relationships with allies, and level of support for the mission among military personnel, to offer several examples. These characteristics must be considered for each mission, since they may serve to modify the training requirements for the mission types developed below.

To create mission profiles, three expert analysts were asked to rate the 16 missions using the characteristics listed in Table 6-1. The analysts included an academic specialist on peacekeeping who is a member of the committee, a major in the Canadian armed services with long experience in peacekeeping operations, and a retired U.S. ambassador with expertise in international conflict management. For each mission, the analysts rated all the characteristics in terms of three possibilities, usually distinguishing among high (or clear), moderate (clear on some tasks, vague on others), and low (vague). To develop consensus ratings, differences among the analysts' ratings were resolved through discussion or, in some cases, by using the middle category as a kind of compromise decision. The final ratings, which took the form of codes ranging from 1 to 3, were used as data for a scaling analysis that reveals similarities and differences among the mission profiles. 1

Scaling Analysis

This exercise and the resulting statistical analyses were designed to discover a pattern of relationships among the missions, one that might serve to organize the discussion of training requirements that follows in the next chapter. The pattern that emerges should be regarded as a hypothesis, since other dimensions could also be discovered. We are interested to know whether the pattern that emerges is useful in distinguishing among the various missions.

The pattern is based on correlations calculated for each possible pair of missions: in this case, all the possible pairs total 120. 2 The correlation coefficient expresses the extent to which two missions are similar in terms of the judgments made across the set of 11 characteristics. In a separate analysis, we were also able to assess the extent to which the characteristics correlated with one another individually. For example, the analysis provides information about the characteristics that relate most strongly to the ease of assessing mission success. This variable was found to correlate positively with clarity of goals (.56) and negatively with mission creep (-.61) and with tolerance of costs (-.48).

It seems that the clearer the mission's goals, the easier it is to assess its success. And the less likely the possibility of mission creep and the more tolerance-constituents have for costs, the more difficult it is to assess mission success. These findings suggest, not surprisingly, that a clear statement of goals provides criteria for judging success. They also suggest that it is easy to judge failure in light of mission creep and high costs, but not easy to assess success when mission creep is less likely and costs are low.

Using a technique referred to as multidimensional scaling, we can capture the complete set of relationships among the missions. (See Kruskel and Wish, 1990, for a discussion of the procedures and applications.) The technique reveals an underlying structure for the complete set of correlations. That structure takes the form of a two-dimensional space that provides coordinates for locating the missions: more similar missions are located in closer proximity in the space.

Broadly speaking, the scaling analysis is used to identify meaningful groupings of the missions and the dimensions along which they are grouped. Although a larger number of dimensions is possible, we limited the number to two, based on satisfying criteria of interpretability, ease of use, and stability. These dimensions organize the missions in terms of relationships and processes that are emphasized in the literature on conflict management. The exercise provides a basis for organizing the discussion in the next chapter on the challenges and skills needed to perform effectively and places it in the context of the research literature. These skills are broadly applicable to a wide variety of conflict situations, including those confronted often by military peacekeepers.

Results of the Analysis

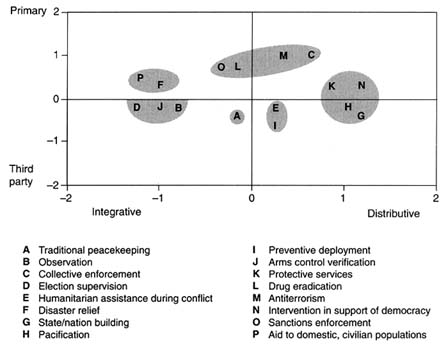

Results of the scaling analysis are shown in Figure 6-1. Two results are of particular interest for our purposes: one is the dimensions themselves, which appear as the north-south and east-west axes of the figure. The other is the clustering of the missions in constellations across the four boxes of the figure.

Dimensions. The distinction between primary and third-party roles clearly divides the missions from north to south. Soldiers in primary roles are principals in the conflict, whereas those in third-party roles are not direct parties to the conflict, but rather mediators or conciliators. Most of the missions in the north quadrants—disaster relief (F), sanctions enforcement (O), drug eradication (L), antiterrorism (M), collective enforcement (C), protective services (K), and intervention in support of democracy (N)—were coded as primary roles for soldiers. Most of the missions in the south quadrants—election supervision (D), arms control verification (J), observation

FIGURE 6-1 Missions across characteristics.

(B), traditional peacekeeping (A), and preventive deployment (I)—involve third-party roles for soldiers.

Two missions—humanitarian assistance during conflict (E) and pacification (H)—were regarded as having elements of both primary and third-party roles; they are located at the "border" between the southeast and northeast quadrants. Only two missions appear to be misplaced: the mixed mission of aid to domestic populations (P) is located in the northwest quadrant with primary missions, and the primary mission of state/nation building (G) is located in the southeast quadrant with third-party missions. A strong correlation between the role variable (each mission coded as primary, mixed, or a third-party role) and the dimension plots supports this interpretation. (The correlation is .70.)

The distinction between integrative and distributive processes divides the missions from west to east, although it is not as clear a distinction as the north-south one. The distinction between distributive and integrative bargaining was made originally in the context of labor-management negotiations by Walton and McKersie (1965). Distributive bargaining refers to processes in which parties attempt to increase their own outcomes (usually money, territory, positions, or power) at the other's expense. By integrative bargaining, we refer to processes in which parties attempt to achieve mutually beneficial solutions to a problem (which may involve either tangible or intangible resources). Parties are concerned with relationships and search for enduring resolutions.

Most of the missions in the west quadrants consist of integrative processes—traditional peacekeeping (A), observation (B), election supervision (D), disaster relief (F), arms control verification (J), and aid to domestic civilian populations (P). The only exceptions are sanctions enforcement (O) and drug eradication (L). Of those in the east quadrants, only state/nation building (G) is integrative; humanitarian assistance during conflict (E) and pacification (H) are mixed; and all the others are regarded as being characterized primarily by distributive processes. The correlation between the mission codes for process (as distributive, mixed, or integrative) and the dimension plots is a moderately strong .51.3

Clusters. The way in which the missions are grouped or clustered in the space may indicate similarities, reducing the 16 missions to fewer, more general types. Using traditional peacekeeping as a point of reference, the clusters of missions can be seen to fan out to the west, north, and east. Five distinct groupings are apparent. To the west (in the southwest quadrant), election supervision (D), arms control verification (J), and observation (B) are grouped together. These missions have in common a monitoring function and are relatively passive. Also to the west but in the northwest quadrant are two nonconflict missions intended specifically to deal with emergencies:

aid to domestic populations (P) and disaster relief (F). To the north (spanning the northwest and northeast quadrants) are the combat-oriented coercive (or offensive) missions: sanctions enforcement (O), drug eradication (L), antiterrorism (M), and collective enforcement (C). To the west and spanning the north and southwest quadrants are missions whose purpose is to restore countries to functioning civil societies: protective services (K), intervention in support of democracy (N), pacification (H), and state/nation building (G). Finally, to the near west are two missions intended to limit damage to conflicting societies: humanitarian assistance (E) and deterrent deployment (I); both these types of missions characterize the United Nations peacekeeping operations in Bosnia and Macedonia in the early 1990s. The five groupings can be viewed as different kinds of challenges to soldiers, each calling for similar sets of trained skills, which we discuss in further detail in the next chapter.4

Needed Skills For New Missions

The distinctions we make among missions call attention to the variety of operations other than war that can be performed by military forces. The various tasks are also likely to call for a somewhat different mix of skills needed to accomplish the mission, although this is not always accepted by the U.S. Army, which states that the "first and foremost requirement for success in peace operations is the successful application of war-fighting skills" (U.S. Department of the Army, 1994:86). In the next chapter, we discuss the kinds of skills that are needed for the various kinds of missions.

Notes

-

2Although some variables were coded in terms of a three-step scale going from "much" to "little," others were coded in discrete categories such as whether the soldier's role was primary, mixed, or third party (see Table 6-1). For this reason, we decided to use a correlation coefficient based on categorical rather than scaling assumptions. This is the gamma coefficient. Interested readers may consult Goodman and Kruskal (1954) for details.