9

Visions on Potential Priorities and Actions for Preparedness by 2030

Session 3 of the workshop culminated in discussions about top priorities and potential actions for strengthening preparedness by 2030—the target date for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all. The session was moderated by Rima Khabbaz, director of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It opened with visionary statements from four panelists about what they identified as the most pressing actions and priorities for improving preparedness and global health security by 2030. Panelists discussed how those efforts could synergize with other global efforts and investments, such as the SDGs, health systems strengthening, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). Harvey Fineberg, president of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, discussed ways to strengthen preparedness capacities by improving public understanding about influenza and by developing new vaccines, diagnostic technologies, and antiviral treatments. Gabrielle Fitzgerald, founder and chief executive officer of Panorama, explored the importance of using a strong advocacy agenda to make preparedness a political priority. Nicole Lurie, former Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), emphasized the need to build preparedness capacities by strengthening day-to-day systems. Ciro Ugarte, director of the health emergencies department at the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), discussed the importance of improving local, national, regional, and international capacities and of overcoming coordination challenges. Finally, to conclude the workshop, Keiji Fukuda, director and clinical

professor, School of Public Health, The University of Hong Kong, provided reflections and some takeaways on potential ways to move forward in order to achieve greater preparedness.

BOLSTERING PUBLIC UNDERSTANDING AND THE ORGANIZATIONAL, RESOURCE, AND TECHNOLOGICAL COMMITMENTS FOR PREPAREDNESS

Harvey Fineberg, president of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, explored several ways to strengthen preparedness and response—with a focus on influenza—in the coming decades. He drew a distinction between panic and preparedness and highlighted the “paradox of indifference” against unknown threats and risks. Gaining political and policy support for preparedness, he said, ultimately depends on the understanding and support of the general public. To promote better understanding, he suggested, public health discussions about influenza pandemics should not use the term “the flu” in connection with preparedness. After decades of misuse in advertising for over-the-counter medications (e.g., for the “stomach flu” or “cold and flu symptoms”), the public perceives “the flu” as an ill-defined and relatively minor ailment. According to Fineberg, rather than trying to change these entrenched public misconceptions, the term influenza, rather than flu, should be always be used to discuss preparedness. This could help promote public understanding that influenza is a unique and serious disease—no other condition has such a severe burden on an annual basis and such a capacity for catastrophic burden on a periodic, non-occasional basis. Influenza should be addressed every year as a serious problem and occasionally as a potentially catastrophic problem, he added. Fineberg also suggested that the distinction between seasonal and pandemic influenza should be discarded in order to bolster public understanding. For example, CDC estimated 80,000 deaths from influenza in the United States in 2017, but on an annual basis, influenza probably causes at least 600,000 deaths worldwide (CDC, 2018). He said that periodically, that number could be 10-fold or even 100-fold greater.

Additionally, Fineberg focused on the need for better organization and greater resource commitments. He noted that the world is still ill prepared to respond to a severe influenza pandemic or to any sustained global public health emergency—this holds for Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome, or influenza. Although there have been successes and substantial improvements in organizational preparedness, such as the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework and pre-agreements with vaccine distributors, he said the shortfalls also need to be recognized. For example, the world currently does not have the capacity to produce 10 billion doses of vaccine in a given year. He said the pandemic preparedness community

“is constantly at risk of either being at fault because we’ve done too much when too little has happened, or at fault because we’ve done too little when too much has happened.”

Finally, Fineberg suggested that adequate preparedness in the future will require progress in three technological domains: vaccines, diagnostics, and antiviral treatments. First, progress with influenza vaccines will require a “quadruple jump” across four main obstacles to attain sustained capacities to protect populations and to allow outbreak response to get ahead of the epidemic curve (see Chapter 3 for more on influenza vaccine challenges and the road to a universal influenza vaccine). He specified that influenza vaccines should be

- effective against all or most strains instead of against a selective, small number of strains;

- more efficacious and protective (ideally at least 90 percent);

- protective for decades rather than a few months; and

- producible on a shorter time scale.

Second, Fineberg remarked that diagnostics that allow people to test themselves at home would swiftly inform the community, caregivers, and public health authorities about influenza conditions that are currently prevalent (see Chapter 4 for more on at-home diagnostics). Finally, he added, better antivirals are also needed to stifle severe influenza and to transform it into a manageable disease—much as the cocktail of antivirals has done for HIV. He suggested that this could facilitate acute case management and potentially reduce the severity of influenza.

POLITICAL PRIORITIZATION AND STRATEGIES FOR PREPAREDNESS

In her presentation, Gabrielle Fitzgerald, founder and chief executive officer of Panorama, remarked that political prioritization of a health issue can create a sea of change in people’s thoughts about how to solve problems. The significant changes effected by political strategies to address malaria, polio, and HIV/AIDS have inspired optimism that similar progress could be made through a concerted effort to develop a political strategy related to address microbial threats and outbreak preparedness. For example, The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief initially received a funding commitment of $15 billion over its first 5 years because there was a concerted effort to prioritize HIV/AIDS on high-level political agendas (UNAIDS, 2018). Similarly, funding for malaria increased dramatically through the President’s Malaria Initiative. Resource mobilization strategies by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and CEPI have also resulted in billions of dollars in new funding.

“Major change can happen when the right political forces align,” Fitzgerald reiterated. She explored how health diplomacy might elicit political action toward readiness for microbial threats. Public health is inherently political, and health diplomacy involves finding ways to incentivize governments to achieve health goals. She said that a sophisticated health diplomacy and advocacy strategy will be needed to promote preparedness issues on political and financing agendas, she said. Although the United States remains the largest funder of global preparedness capacity, other countries could also fill leadership roles if they were engaged and if they had the support to do so. She suggested that philanthropists could also be agents of change, as demonstrated by global foundations that have leveraged philanthropic dollars to encourage others to act. For example, an initial $540 million was raised for CEPI through a catalytic coalition led by Norway and the Wellcome Trust.1 She also highlighted the potential to accelerate the pace of change through collective efforts driven by a unified coalition of entities working on preparedness.

Fitzgerald described some priority changes for which a political strategy around outbreak preparedness could advocate. In a recent publication, global health scholars reviewed progress that has been made in areas of needed improvement2 that were identified by post-Ebola panels and commissions (Moon et al., 2017). Significant improvement was found in only two areas: WHO’s preparedness and response capacity had improved with the creation of the Health Emergencies Programme, and progress toward developing new vaccines had improved with the creation of CEPI. Although many countries had completed the Joint External Evaluation (JEE) process, few had costed the plan, and little financing was available for countries to implement the JEE recommendations. In most other areas, progress was incremental or very limited. Fitzgerald maintained that a political strategy should highlight this general lack of progress in broader global health and national security conversations.

Fitzgerald was hopeful that investment in health diplomacy and advocacy would help break the cycle of panic and neglect in preparedness. Quoting Lawrence H. Summers, Charles W. Eliot Professor and president emeritus of Harvard University, Fitzgerald noted that pandemics and epidemics have the highest ratio of global seriousness to policy attention, but relative to their significance to humanity, no other issue receives less attention. To help shift this ratio, she suggested advocating for several

___________________

1 For more information on CEPI investments, see https://cepi.net/news (accessed March 22, 2019).

2 The eight areas of needed improvement were leadership and monitoring, financing, national health systems capacity, the role of WHO, the humanitarian aid system, research and development of health technologies, knowledge sharing, and trade and travel restrictions.

specific improvements: leadership, coordinated planning efforts, and increased and sustained funding. Although WHO has improved capacity to manage outbreaks, she noted, it is not positioned to respond to a global crisis or pandemic. She suggested that to improve leadership, the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General needs a standing mechanism to prepare for and to coordinate across all areas of a pandemic response. A coordinated planning effort would involve an overarching global plan that articulates all of the needed areas for improvement and that regularly measures and tracks progress. Finally, Fitzgerald suggested that increased and sustained funding would support (1) the implementation of countries’ JEE plans, (2) overall WHO operations and the WHO contingency fund for emergencies, and (3) research and development of new diagnostics.

BUILDING PREPAREDNESS CAPACITIES ON DAY-TO-DAY SYSTEMS

Nicole Lurie, former Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at HHS, drew on her experiences with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, CEPI, and the World Bank. She observed that in most countries, outbreak preparedness needs generally do not align with the population’s other critical needs. That is, compared to outbreak mortality, more people worldwide die every day from hunger, poverty, violence, and routine infections such as malaria or cholera. Consequently, neither acute infectious disease outbreaks nor noncommunicable diseases, which increasingly affect people across the world, tend to be a priority in most countries—including the United States. She noted that the two issues are rarely considered in the same context, despite the generic skillset that would provide the first line of defense for both in terms of workforce, infrastructure, and public health. Lurie noted that outbreak-related research focused on a single disease is not sustainable, especially in developing countries, because it tends to be funder-driven and to dissipate when the disease du jour has grown quiet. Investment priorities should broaden beyond emerging infectious diseases to include multipurpose investments that link capacity-building efforts to outbreak preparedness, Lurie said. This would help ensure that both the day-to-day health concerns of governments and the interests of the global community are being addressed.

Potential Priorities for Capacity Building

Lurie maintained that preparedness should be built on day-to-day systems so that outbreak response occurs through systems already in place. Funding and interest in capacity building that arise during crises, she added, should be used to strengthen those day-to-day systems. She suggested that

surveillance systems should be multipurpose and should cover noncommunicable diseases as well as outbreaks; a robust and flexible system should be able to pivot to detect and respond to an outbreak signal. Over time in the United States, most of the funding for surveillance has shifted to a budget for preparedness, which must constantly be adjusted to deal with all types of diseases. The organization of these efforts needs to be reconsidered and restructured, she said.

Strengthening health systems is another priority, Lurie said, because the ability to deliver basic medical care is critical to outbreak preparedness. Basic capacities are often taken for granted, but in many parts of the world, providers are unable to oxygenate patients with influenza or administer basic intravenous fluids to patients with Ebola. Deficits in basic health care must be addressed in settings where responders cannot wash their hands or where intravenous fluids are not available. She suggested that the U.S. government could engage more robustly in supporting developing countries’ efforts to build health systems that at least have basic capacities.

Making a Business Case for Capacity Building

Lurie explained that the business case for investment should focus on generic skillsets that apply to noncommunicable diseases as well as outbreak preparedness. Framed appropriately, she said, this could also attract more private-sector interest and momentum among parties investing in developing countries that need more functional surveillance and health delivery systems. She also suggested focusing on how to use existing funding more effectively rather than seeking more money in aggregate. Funders are currently channeling money into capacity building and preparedness in a siloed way. She noted that synergizing all the existing funding sources could optimize the results. At a minimum, better transparency and organization would make it easier for countries to deal with the large number of different funders.

Research and Development Priorities

Research should be a component of every outbreak response, Lurie said, because every outbreak presents opportunities to ask and to answer important questions. She suggested building a system to develop organized research capacity that could be executed when needed. This would require national and global systems to expedite the flow of research funding during a crisis and to build a strong system of global governance around research, she said. CEPI’s commitment to fund research in the critical path for vaccine development is a positive development in this regard.

Additionally, Lurie suggested that vaccine manufacturing should be restructured. CEPI’s mandate is to develop novel vaccines, move them

through Phase II studies focused on assessing efficacy, and then potentially test them during an outbreak. If one of the vaccines proved effective, the existing system would not have the capacity to produce billions of vaccines fast enough. It would require large investment and creativity, she said, to create more nimble, sustainable, and decentralized manufacturing capacities.

Finally, she said that an understanding of the culture, beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes of a given population is central to any outbreak response, regardless of the setting. Lurie suggested that anthropologists and social scientists should be deployed to better understand how to engage the population in outbreak control activities, such as accepting vaccines or using at-home diagnostic tools.

IMPROVING LOCAL, NATIONAL, REGIONAL, AND GLOBAL CAPACITIES FOR PREPAREDNESS: A PERSPECTIVE FROM THE PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION

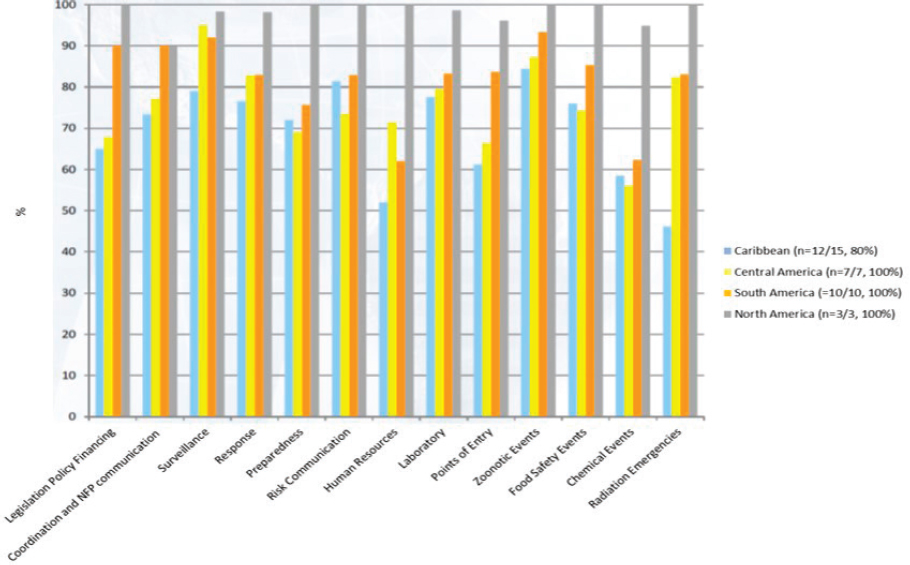

Ciro Ugarte, director of the health emergencies department at PAHO, explored some of the challenges to and priorities for preparedness from his experiences working at an international health agency in the Americas. He began by discussing the evolution of PAHO countries’ core International Health Regulations capacities between 2011 and 2018, as they were reported annually to the World Health Assembly. Overall, the trend was generally positive, although capacities declined in some areas, such as human resources and funding, which reflects general challenges faced in the health sector. The core capacities to deal with emergencies were more disparate when divided by sub-regions in the Americas (see Figure 9-1). For countries with a limited capacity to respond to an emergency, he said, the highest priority is to protect their own populations. This makes governments less likely to share information, and they may even actively deny that a disease is present. Countries are also more likely to delay the process of reporting. He noted that although the number of reported events has increased among countries in the Americas, reporting often has been delayed by as many as 10 days (rather than 24–48 hours).

PAHO’s Priorities for Improving Preparedness

Ugarte highlighted a set of priorities for improving preparedness-related capacities in the PAHO region. Developing institutional capacity is a priority, he said, because institutions and governance need to be properly designed and prepared to respond to large emergencies. Additionally, he noted that information management should be improved, such as centralized data collection and information sharing. Information sharing can be

NOTE: NFP = National Focal Point.

SOURCES: Ugarte presentation, November 28, 2018; data from WHO Global Health Observatory.

politically sensitive because of concerns about the economic impact of a publicized outbreak or concerns that the health sector will be blamed if an outbreak occurs. He said that developing a multisectoral approach is another priority because health sectors tend to be weaker than other sectors in terms of influence, funding, workforce, and response capacity. Strengthening regional solidarity and creating a mutual support system would be ways to cope with such challenges, and he cited the effective cooperation among Caribbean states as an example. Ugarte noted that resources devoted to preparedness efforts should be balanced with resources for countries’ more urgent priorities.3

He said PAHO has identified five lines of action to address its preparedness priorities. Those actions include

- incorporating health crisis response into overall disaster plans and programs;

- developing human resource capacities;

- ensuring the provision of authoritative information since ministries of health often lack the authority to report information without higher-level political clearance;

- strengthening laboratory capacity; and

- improving early warning, surveillance, and response.

Challenge of Coordination

Both national and international preparedness and response capacities are critical, Ugarte said. A comprehensive approach should improve the coordination of international actors in a way that is integrated with strengthening national capacities. Coordination is the major challenge, he said, because “everybody wants to coordinate, but nobody wants to be coordinated.” Various institutions have their own mandates, protocols, and processes that can be difficult to coordinate effectively during a response.

Ugarte used examples from the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic to illustrate the need for better coordination to achieve optimal benefits for an affected country. Prior to the pandemic, he said, UN agencies had been important partners supporting countries in strengthening preparedness. During the H1N1 pandemic response in Mexico, however, he said UN agencies drastically reduced their participation and tended to portray

___________________

3 For example, outbreaks of measles and rubella have occurred in several countries in the Americas because the vaccine coverage has dropped below the first order of protection. This triggered a meeting among the region’s ministers of health at PAHO to discuss the health implications of massive migration because blame was being placed on countries that were releasing migrants without vaccines.

their agencies as “victims” that needed more attention than Mexico. UN agencies withdrew many of their staff in the country at the same time that PAHO and WHO significantly increased their staff in Mexico, he said. Similarly, the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network missions, coordinated by PAHO, helped some countries by providing opportunities for knowledge and information exchange. However, according to Ugarte, all of these factors led to an uncoordinated influx of foreign aid, and some network members maintained their institution’s objectives or interests, which created differences and potential conflicts with the PAHO response team. For example, he reported that some actors sought to increase their own country’s preparedness by sending home sensitive information without the adequate level of clearance and transparency.

Ugarte concluded that, ultimately, preparedness priorities should aim to enhance national and international capacity by strengthening and complementing local response capacity and improving the quality and appropriateness of external assistance. He emphasized the need for political endorsement of guidelines on how improve the quality of international cooperation, which is necessary to maintain the political will for preparedness efforts. Ensuring coordination among specialized organizations, agencies, centers of excellence, and relevant partners is also a way forward, as is the establishment of operational coordination procedures with national, regional, and global initiatives. Ugarte suggested focusing on excellence rather than visibility and on effectiveness rather than convenience. Both actual and perceived risks can motivate decisions that are not aligned with the desired priorities. Thus, emergency situations—whether actual or perceived—can be leveraged to increase political awareness of the importance of preparedness. He concluded that the potential impacts and benefits of bolstering pandemic preparedness should be couched in the appropriate political and economic language.

DISCUSSION

Following the presentations, Rima Khabbaz, director of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases at CDC, highlighted that some strategies for pandemic preparedness would benefit from different ways of thinking, different ways of acting, bringing different people to the table, and using different language to discuss the issues. Panelists touched on issues related to changes in organizational capacities and resource commitments that may integrate outbreak and pandemic preparedness. Although successes have been achieved through vertical investment in specific diseases, multipurpose investment and investment in credible local-level institutions that conduct day-to-day work are potentially useful strategies. Finally, she noted that investment in technologies

such as vaccines, diagnostics, and antivirals could also help to drive progress.

Some Immediate Priorities for Preparedness

To open the discussion, Khabbaz asked panelists to identify the most pressing, immediate step that should be taken to advance preparedness. Fineberg replied that the answer depends on the time horizon for the desired improvement. If the aim is to leverage existing technologies and tools, then the focus should be on organizational preparedness. If the aim is to lay the groundwork for improving the culture of response among the population, then the focus should be on improving public understanding of the importance of preparedness. Furthermore, if the aim is to establish the strongest position possible by 2030, then he said the focus should be on investing in research and in the development of necessary technologies. He suggested that a sensible strategy would be somewhere in the middle—making adjustments and investments to improve immediate capacity while also creating the possibility of dramatically better capacity in the future.

Lurie remarked that the investment portfolio for preparedness should include long-term investments coupled with short-term investments that achieve incremental change toward building the future system. However, it can be challenging to engage politicians to advocate for longer-term investments for which they will receive no credit for because they will no longer be in office when the investments come to fruition. Fitzgerald added that advocacy is a critical piece in an investment portfolio because it has the biggest leverage play—a $1 million investment in advocacy can yield a 500-fold return on investment.

Fitzgerald also suggested conducting network mapping to identify key players, their priorities and targets, and the ways in which they can be encouraged to contribute to a unified political movement around the preparedness agenda. She noted that many advocacy organizations, philanthropists, and high-level experts would probably be interested in forming a coalition or constituency. However, she said funding would be needed to accelerate those efforts. She suggested the need to strengthen and improve existing funding mechanisms rather than creating a new global funding mechanism for outbreak preparedness, which might be less politically palatable.

Ugarte remarked that although health emergencies have large impacts across many nonhealth sectors, the health sector is generally the hub of information about an outbreak. Multisectoral emergency management institutions may be reluctant to take the lead in a response because he said many are averse to the burden of responsibility. Multisectoral collaborations could be improved if the health sector worked more closely

with other sectors to strengthen general public health and well-being as well as outbreak response. He added that issues related to antiviral stockpiling are also a priority because many developing countries do not have the luxury of stockpiling, and if they do, they risk wasting limited resources if the drugs expire unused.

Building Support for Preparedness Across Sectors

Keiji Fukuda, director and clinical professor, School of Public Health, The University of Hong Kong, commented that in the context of addressing antimicrobial resistance, gaining multisectoral support and political buy-in are both important factors. Pandemic preparedness generally has the support of major scientific and technical bodies, but it lacks multisectoral support and a political champion. He asked about ways to shift the issue of preparedness from a technical to a political frame in order to gain the needed support. Fitzgerald replied that recruiting political champions is critical since they can leverage their existing relationships and engage in diplomatic outreach to bring others to the table—as modeled by CEPI. However, she remarked that each country and political environment needs a tailored approach.

Kumanan Rasanathan, board director of Health Systems Global, noted a tension between two agendas. The traditional technical agenda is focused on diagnostics, vaccines, and surveillance capacity. What needs to be done for this agenda is clear, but the necessary resources and political will are lacking. The other agenda is more focused on health systems strengthening and on engaging more players from all sectors of society in combined efforts to mainstream preparedness activities. Tensions between these agendas are evidenced by increasing public and private-sector investment in health systems around the world and by attempts to push for universal health care. He suggested that the agendas are not mutually exclusive, but the latter will warrant changes in messaging and cross-sectoral engagement with the broader community. Ugarte added to Rasanathan’s comments by noting the importance of identifying what the health systems strengthening agenda needs from the emergencies perspective, and highlighted that antimicrobial resistance and infection prevention and control issues are core elements of health systems and need to be addressed. Efforts in that area may provide mutual, compounding benefits.

Lurie agreed that this tension existed and noted an additional need to share power, information, and influence to bridge these agendas. She added that one challenge to promoting multipurpose investment is the disparity between the investments that governments of developed countries assume developing countries need and those that governments of developing countries actually consider necessary. She suggested bringing

new players to the table so that they can contribute and engage with each other in a coordinated way. For example, she highlighted that the private and business sectors have expertise in operations, logistics, supply chains, and other capacities that are necessary to respond to an outbreak. Lurie further remarked that moving forward with preparedness would require cross-sectoral coordination, recognition, and respect. She referred to points raised in the earlier small-group discussions, which positioned the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) model as an example of an effective structure for complex interactions across a broad range of sectors and players (see Chapter 8 for more on the potential for a FEMA-style model). Fitzgerald also suggested establishing a FEMA-style model at a level higher than WHO, which currently lacks the mandate to bring many nonhealth players to the table, but a UN coordinating mechanism could serve that function.

Suerie Moon, director of research at the Global Health Centre at The Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, reiterated the importance of coordination during a crisis because gaps in coordination can cause wasteful duplication of efforts. She asked if enough information is available and accessible to facilitate regional or global coordination in preparedness. Ugarte replied that information is available, but it is not sufficient for that level of coordination. However, he noted that in addition to increasing information-related capacities, it is also important to adjust communication and negotiating styles to foster organizations’ willingness to coordinate, participate, and contribute in a collective way to strengthening preparedness.

Rafael Obregon, chief of communication for development section of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), asked about ways to encourage interest and investment in the social science component of outbreak preparedness and response, noting that both WHO and UNICEF have taken some initial steps to strengthen that component. Lurie commented that people with social science skills are widely available and could be engaged in preparedness through creative, effective communication strategies and through innovative approaches such as tailored, just-in-time training. Obregon also asked about strategies to encourage investment into under-resourced, local-level health systems, which would build capacity, trust, and community engagement. Ugarte replied that political and strategic support for local-level systems can sometimes have an even greater impact than the actual value of financial investments, because they can engage local decision makers in the solution-finding process. This can be made difficult by the multilevel governance structures in decentralized countries, but it is possible to create these lasting bridges of health diplomacy in order to engage local officials in traditionally hard-to-reach settings.

CLOSING REMARKS

Fukuda closed the workshop by observing that the process of preparedness has core components and evolving aspects. He highlighted that a core component is the need to address the full spectrum of priorities and perspectives at the community, national, and global levels. Another core component, he added, is the need to focus, harmonize, and ensure functionality across a range of areas, including global governance, political attention and will, science and technology, operations on the ground, legal concerns, and trust-building. He suggested that preparedness efforts should target specific, focused steps to achieve continuous incremental gains within the broader, highly complex preparedness enterprise, with care taken to avoid fragmentation or silos. For example, vaccines are generally considered to be relatively technical and scientific work, but vaccines are also related to a broader scope of issues that can create stumbling blocks, such as on-the-ground operations, administrative and bureaucratic processes, and liability issues. Such issues, he noted, warrant as much attention as vaccine development and universal vaccine design.

Fukuda said that some countries and territories, such as Hong Kong, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and Liberia, have made substantial improvements in overcoming challenges and strengthening preparedness capacities. The hope is that other countries could achieve similar progress without having to repeatedly experience crises. Fukuda envisioned that, ideally, preparedness would be positioned not only as a mechanism to respond to extraordinary and unusual situations but as an expected and required tenet in the activities delivered by bureaucracy, funding and technical organizations, and all sectors including and beyond health.

At the national level, Fukuda said, it is important to bring all stakeholders to the table. He underscored that particular attention is needed within national bureaucracies to empower and to implore agencies to act on preparedness and to convince political leadership of the importance of those actions. Governments should also focus on building trust with communities and providing them with the guidance they need to prepare and protect themselves, he said, because communities are the “energy supply” of the world, not global institutions and organizations.

At the global level, Fukuda reflected, it will be critical for the “politics of making progress” to tap into existing mandates and tools—including the SDGs and the global push for universal health coverage—to ensure that the efforts to strengthen preparedness are seen not as isolated issues but as contributing to a greater whole. At the same time, other capabilities for other diseases should be applied to pandemic preparedness. Different international organizations should be equally supported in their global-level preparedness strengthening activities, Fukuda added. Furthermore, to

ensure that the benefits of the PIP Framework are not lost, he said international mechanisms to share information and benefits need to be updated in a way that is transparent, understandable, and equitable. Fukuda urged these efforts should focus on creating platforms for sustainable cooperation toward mutually agreed-upon goals rather than on building yet another mechanism of coordination.

This page intentionally left blank.